Update/Commentary

Since our original article was published, the treatment landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has evolved rapidly. The recently approved agents for front-line CLL therapy (obinutuzumab and ibrutinib) demonstrate a favorable toxicity profile, making them excellent treatment options for elderly CLL patients. Obinutuzumab, an Fcγ-engineered anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, combined with chlorambucil, improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with chlorambucil alone in untreated elderly patients with CLL and comorbid conditions.1 The regimen was well tolerated. Therefore, obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil was approved for front-line CLL treatment. In elderly untreated patients with CLL without del(17p13.1), ibrutinib, an oral inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, demonstrated significantly improved overall response and overall survival rates compared with chlorambucil-treated patients.2 In other studies, similar efficacy was noted in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients with and without del(17p13.1).3 Ibrutinib was well tolerated. Uncommon but serious (≥ grade 3) adverse events in ibrutinibtreated patients were atrial fibrillation (≈ 6%) and major bleeding (1-4%, especially in patients receiving warfarin). Subsequently, ibrutinib was approved for all frontline CLL patients. Based on the availability of these novel therapies, our previous treatment algorithm must be revised. If an elderly untreated CLL patient does not 1) require anticoagulation with warfarin, 2) have uncontrolled atrial fibrillation, or 3) have malabsorption, ibrutinib should be considered. If the patient has one of the listed comorbid conditions and does not express del(17p13.1), obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil or the less-favored bendamustine plus rituximab regimen should be considered. In the setting of comorbid conditions and expression of del(17p13.1), high-dose methylprednisolone plus rituximab therapy should still be considered. In summary, approval of the novel agents obinutuzumab and ibrutinib have established a new standard of care for elderly patients with CLL.

Updated References

The Question

Is there a standard of care for treating older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)?

Our Response

Despite recent progress in the understanding and management of CLL, the disease remains essentially incurable. Incidence of CLL is significantly higher in the elderly (those > 65 years old), as the median age at diagnosis is 72 and an estimated 70 percent of newly diagnosed patients are over 65.1 Despite the predominance of elderly CLL patients, this group has been underrepresented in clinical trials because many have major medical co-morbidities or are perceived likely to tolerate therapy poorly. This omission leaves clinicians who treat CLL without definitive data on which therapy to choose for the large population of older adults.

At initial presentation, the clinical spectrum of CLL ranges from an asymptomatic patient, identified by routine blood work, to a symptomatic patient who experiences rapid progression to death from complications of CLL. Therefore, the first decision to make is whether or not treatment is required. Indications for consideration of treatment include: clinical symptoms (fevers, night sweats, weight loss, or painful lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly), nonimmune-mediated cytopenias (hemoglobin < 11g/dl or platelets < 100x1012/L), autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or thrombocytopenia (ITP) that is poorly responsive to standard immunosuppressive therapy and rapidly progressive disease (lymphocyte count rising to > 300x109/L or rapidly enlarging lymph nodes, spleen, or liver). Isolated mild thrombocytopenia (platelets 70-100x1012/L) often represents chronic ITP and can be followed closely without treatment if symptoms are absent.

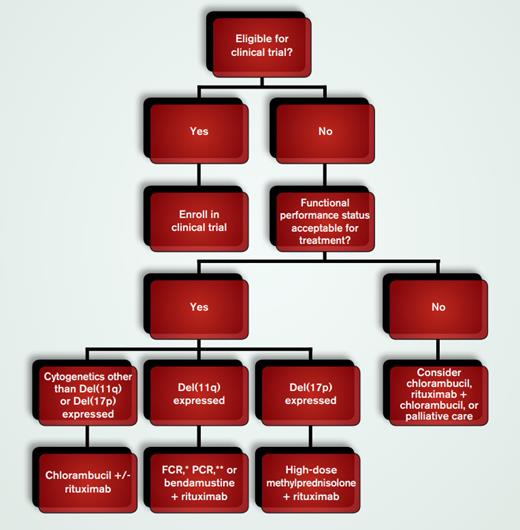

Therapeutic Recommendations for Elderly Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia who Meet Criteria for Therapy. *FCR=fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab; **PCR=pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab

Therapeutic Recommendations for Elderly Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia who Meet Criteria for Therapy. *FCR=fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab; **PCR=pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab

Treatment decisions can be informed by identifying factors that influence response rates, duration of response, and prognosis, including specific interphase cytogenetic abnormalities such as del(17p13.1) and del(11q22.3), complex cytogenetics (> 3 abnormalities) determined by stimulated metaphase karyotype, unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain gene status, Rai stage III/IV, Zap-70 expression in 20 percent or more of peripheral blood lymphocytes, and elevated serum β2–microglobulin concentration. Trials by the German CLL Study Group have factored in co-morbid features assessed by the CIRS-G scale2 for choosing therapy in elderly patients; however, this score is subjective, and, to date, no study has documented the benefit of this scale over simpler methods. Only performance status and the presence of del(17p13.1) or del(11q22.3) influence our treatment choice (Figure).

If an elderly CLL patient requires therapy and is eligible for and willing to participate, we recommend enrollment in a clinical trial. Outside of a trial, if the patient’s performance status will allow therapy, he or she should be assigned to one of three groups according to the presence of FISH/cytogenetic abnormalities: del(17p13.1), del(11q22.3), and all others.

Standard frontline therapy for younger patients with cytogenetic abnormalities other than del(17p13.1) or del(11q22.3) is the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR)or fludarabine and rituximab. However, a subset of CLL patients ≥ age 60 in a large study of frontline therapy with FCR were more likely to require early treatment discontinuation due to myelosuppression and other non-hematologic toxicities,3 which likely limits the clinical benefit of the regimen in this population. In addition, Eichhorst et al. compared firstline CLL therapy consisting of either fludarabine or chlorambucil in a group of 193 patients ≥ 65 years. Although fludarabine improved the overall response rate (ORR), improved the percentage of complete remissions (CR), and increased the time to treatment failure, there was no difference in progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) between the two groups. Notably, the fludarabine group demonstrated a shorter median survival time and higher rate of toxicity, indicating that there is no major clinical benefit of using fludarabine over chlorambucil in the older population.4 These findings were confirmed by Woyach and colleagues5 who reviewed the experience of elderly CLL patients across all completed Cancer and Leukemia Group B trials and demonstrated no benefit for fludarabine treatment in patients > 70 years. In contrast, patients of all age groups appeared to benefit from the addition of rituximab. Recently, Hillmen and colleagues published a phase II trial in which rituximab was combined with chlorambucil in 50 patients (median age = 70.5 years). ORR was 84 percent, with infection and neutropenia being the most common adverse effects.6 Therefore, for an elderly CLL patient without either del(17p13.1) or del(11q22.3), we recommend therapy with chlorambucil (10 mg/m2 orally days 1-7 of a 28-day cycle) +/- rituximab (375 mg/m2 day 1, cycle 1 and 500 mg/m2 day 1, cycles 2-6).

Patients with del(11q22.3) do not have favorable outcomes in the absence of fractionated alkylator-based therapy. For older CLL patients with del(11q22.3), we recommend therapy with FCR, PCR (pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab) or bendamustine (70 mg/m2 days 1 and 2 of 28-day cycle) and rituximab (375 mg/m2 first cycle, 500 mg/m2 subsequent 5 cycles). Using the latter regimen, Fischer et al. reported an ORR of 90.9 percent in 117 patients (median age = 64 years) with minimal major toxicities. A subgroup analysis of patients with del(11q22.3) showed a 90.5 percent ORR.7

Treatment options are limited for older patients with del(17p13.1). Many propose the use of alemtuzumab, but we don’t recommend this therapy due to significant risk of infectious complications and limited response duration. Instead, we recommend rituximab (375 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks) in combination with high-dose methylprednisolone (1 g/m2 days 1-3 of each 4-week cycle). Using this regimen, James and colleagues reported that in a relatively small study of 28 patients (29% ≥ age 70) the ORR was 96 percent (100% in the > 70-year-old subset) with CR observed in 32 percent (38% in > 70 years). Adverse effects were found to be minimal.8 In general, for patients being treated with this regimen, we recommend hospitalization during the first three days of cycle 1 as tumor lysis syndrome, metabolic aberrations, and fluid retention can occur.

For elderly, unfit patients without del(17p13.1), for whom we have concerns that therapy will be poorly tolerated, we typically recommend chlorambucil or rituximab alone or palliative supportive care. Elderly, unfit patients with del(17 p13.1) are unlikely to respond to either of these therapies and should be directed to supportive care.

In summary, due to paucity of definitive data on management of the elderly CLL population, we encourage enrollment of these patients in clinical trials. However, when enrollment in a clinical study is not feasible, we use a treatment approach based on FISH/cytogenetic analysis together with our assessment of the individual patient’s capacity to tolerate therapy (Figure). The CLL treatment landscape is evolving rapidly. Promising new therapies that are currently undergoing clinical trials include lenalidomide, ibrutinib, GS1101, ofatumumab, GA101, ABT-199, and TRU-016. While we await the outcome of these and other studies, a carefully considered approach to the management of elderly patients with CLL is essential.

References

Author notes

The update/commentary section was added in 2016 when this article was included in the Ask the Hematologist Compendium 2010-2015Ask the Hematologist Compendium.

Competing Interests

Dr. Stephens and Dr. Byrd indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.