The findings of this study from the laboratory of Glen Raffel at the University of Massachusetts Medical School provide new insights into the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal, transformation to leukemia, and stem cell aging.

One-Twenty-Two-1 (OTT1) was first identified as a fusion partner with MKL1 in the t(1;22) translocation acute megakaryocytic leukemia (AMKL). (OTT is also called RBM15, as it as the 15th RNA binding motif protein to be named.) To understand the role of OTT1 in the OTT1-MKL1 fusion protein, investigators needed to study the function of OTT in normal hematopoiesis. Previous studies had shown that Ott1in murine cells is differentially expressed during hematopoiesis and may act to inhibit myeloid differentiation. It is expressed at the highest levels in hematopoietic stem cells and at progressively decreased levels during myeloid differentiation. When Ott1 levels are artificially decreased using RNA interference, there is increased differentiation. Conversely, enforced expression inhibits differentiation.

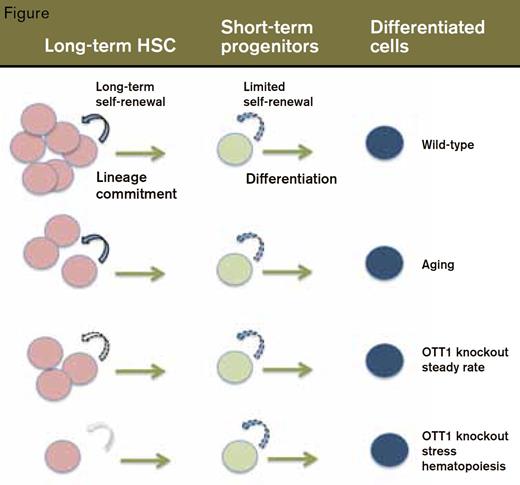

Shown in the top row are (wild-type) bone marrow cells (top) progressing from long-term self-renewal of HSCs to transient self-renewal of shortterm progenitors to fully differentiated cells. The rows below show the parallels between steady-state Ott KO hematopoiesis and normal aging, and the HSC exhaustion that occurs in Ott KO BM under stress, which is analogous to aged HSCs under stress.

Shown in the top row are (wild-type) bone marrow cells (top) progressing from long-term self-renewal of HSCs to transient self-renewal of shortterm progenitors to fully differentiated cells. The rows below show the parallels between steady-state Ott KO hematopoiesis and normal aging, and the HSC exhaustion that occurs in Ott KO BM under stress, which is analogous to aged HSCs under stress.

The investigators assessed the effects of knocking out Ott1 in cells of the mouse hematopoietic system. Under steady-state conditions, deletion of the Ott1 gene had no significant effect on peripheral blood counts or bone marrow cellularity. In contrast, under stress conditions that require HSC self-renewal, lack of Ott1 led to increased cycling and rapid loss of HSCs (Figure). For example, in contrast to wild-type mice, mice lacking Ott1 had impaired hematopoietic recovery following treatment with 5FU and died after 10 to 14 days. Also, BM cells from Ott1 knockout mice failed to engraft into lethally irradiated, wild-type recipients, an even more demanding test of HSC expansion capacity.

Potential mechanisms leading to stem cell exhaustion were examined. While there was no apparent increase in apoptosis or senescence of Ott1 KO cells, there was evidence of loss of quiescence, DNA damage, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, inhibition of ROS production by anti-oxidant treatment did not rescue the HSC defect.

When the investigators compared the gene expression pattern of Ott1 KO with that of wild-type HSCs, they found that many genes were differentially expressed. What did this list look like? It was amazing! There was a very high degree of similarity between this list and the list of genes that are differentially expressed in aged versus young mice. How aging affects the function of adult stem cells, which regenerate our tissues, is not yet known. Therefore, it is very illuminating that loss of Ott1 seems to molecularly mimic aging of HSCs. Also, like Ott1 knockout cells, HSCs from old mice are less effective at engrafting the bone marrow of lethally irradiated recipients and have a higher likelihood of being in the cell cycle (decreased quiescence).

In Brief

How, then, does loss of Ott1 reveal clues about leukemogenesis? For one thing, the risk of leukemia increases with aging, and the leukemic transformation in this case may be at least in part due to more frequent mitotic cycling. In the case of AMKL associated with the t(1;22) translocation, the OTT1 allele that is fused with MKL1 is no longer able to make normal OTT1, which means that the leukemia cells may have half of the normal amount of OTT1. Also, it is not yet known whether the OTT1-MKL1 fusion protein blocks the function of normal OTT1. It will be interesting to find out the hematopoietic phenotype of Ott1-/- mice in which OTT-MKL is expressed.

In summary, there is a significant phenotypic overlap between Ott1-deficient and aging hematopoiesis, including impaired HSC self-renewal and decreased stress response. Whether loss of Ott1 function and aging contribute to leukemogenesis via analogous mechanisms remains to be shown.

Competing Interests

Dr. Krause indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.