Most existing evidence regarding junction protein movements during transendothelial migration of leukocytes comes from taking postfixation snap shots of the transendothelial migration process that happens on a cultured endothelial monolayer. In this study, we used junction protein–specific antibodies that did not interfere with the transendothelial migration to examine the real-time movements of vascular endothelial–cadherin (VE-cadherin) and platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) during transmigration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) either through a cultured endothelial monolayer or through the endothelium of dissected human umbilical vein tissue. In either experimental model system, both junction proteins showed relative movements, not transient disappearance, at the PMN transmigration sites. VE-cadherin moved away to different ends of the transmigration site, whereas PECAM-1 opened to surround the periphery of a transmigrating PMN. Junction proteins usually moved back to their original positions when the PMN transmigration process was completed in less than 2 minutes. The relative positions of some junction proteins might rearrange to form a new interendothelial contour after PMNs had transmigrated through multicellular corners. Although transmigrated PMNs maintained good mobility, they only moved laterally underneath the vascular endothelium instead of deeply into the vascular tissue. In conclusion, our results obtained from using either cultured cells or vascular tissues showed that VE-cadherin–containing adherent junctions were relocated aside, not opened or disrupted, whereas PECAM-1–containing junctions were opened during PMN transendothelial migration.

Introduction

Interendothelial adhesive junctions are formed by a variety of transmembrane adhesive proteins, many of which are directly or indirectly linked to cytoskeleton to form complex structures.1 These junction complexes are important not only in maintaining the structural integrity of vascular endothelium but also in controlling the vascular permeability to macromolecules as well as to leukocytes. Of the many adhesive proteins, both platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1)2-5and vascular endothelial–cadherin (VE-cadherin)6-8 are believed to play crucial roles in the gating step of transendothelial migration of leukocytes.

Intuitively, the process of leukocyte transmigration across endothelium should involve the opening of some interendothelial junctions. How these adhesive molecules behave when leukocyte transendothelial migration happens is an interesting subject that has not been thoroughly examined. It has been proposed that for leukocytes to pass between endothelial cells, the adhesive interactions of these junction proteins must be disrupted either through surface-bound elastase or by activating adhesion-mediated intracellular signaling (for reviews, see Muller9 and Kvietys & Sandig10). However, there have been some controversies about whether VE-cadherin complexes are disrupted when polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) transmigration happens. It has been reported that the VE-cadherin complexes are disrupted when PMNs adhere to the endothelial monolayer.6,7 This viewpoint is supported by the fact that PMNs express numerous proteases, especially the VE-cadherin–cleaving elastase that is preferentially localized at the migrating front of platelet-activating factor-treated PMNs.11,12 However, migrating monocytes or monocytic cell lines that lack PMN elastase also induce focal loss in the staining of adherens junction proteins, including VE-cadherin.8 Besides, the degradation of other adherens junction proteins during PMN adhesion/transmigration can be attributed to a postfixation artifact.13

It is desirable to examine the dynamic sequence of the movement of junction proteins during leukocyte transendothelial migration in living specimens, preferably in vascular tissues. A methodologic choice for this kind of approach would be directly tracing the movements of immunostained junction proteins under a fluorescence microscope. Although monocytes are capable of transmigrating through a cultured endothelial cell monolayer that was prestained with anti–PECAM-1 antibody and fluorescently labeled secondary antibody,8the dynamic movements of PECAM-1 staining pattern has not been documented. Recently, the real-time imaging of VE-cadherin in the same model system has been reported by using a VE-cadherin/green fluorescence fusion protein construct.14 According to this recent report, transmigrating leukocytes apparently push aside this fusion protein, and the displaced material subsequently diffuses back to refill the original “gap.” Whether similar conclusions can be extended to other junction proteins and to leukocyte transmigration through the intact endothelium on vascular tissues remain to be established.

In this study, we used junction protein–specific antibodies that did not interfere with the transendothelial migration to examine the real-time movements of VE-cadherin and PECAM-1 during transmigration of PMNs either through a cultured endothelial monolayer or through the endothelium of a dissected human umbilical vein tissue. With detailed descriptions of the moving behaviors of these 2 junction proteins during PMN transmigration either in culture or in tissue, our results are in favor of a dissociation-reassociation process for PECAM-1 and a pushed aside–coming back process for VE-cadherin at the intercellular boundary. Part of our current results also extended a previous study monitoring VE-cadherin/green fluorescence protein fusion construct movements in a cultured endothelial cell monolayer.14

Materials and methods

Materials

Collagenase, endothelial cell growth supplement, formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP), Ficoll-Hypaque, and heparin were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Fetal bovine serum and medium M199 were from Gibco (Gaithersburg, MD). Monoclonal antibody against human VE-cadherin (clone TEA1/31) was purchased from Immunotech (Marseille, France), and monoclonal antibody against human PECAM-1 (clone 158-2B3) was from Ancell (Bayport, MN).N-(3-triethyammoniumpropyl)-4-(4-(dibutylamino)styryl)pyridinium dibromide (FM 1-43) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Preparation of PMNs

PMNs were isolated from human peripheral blood by centrifugation on a discontinuous Ficoll-Hypaque gradient according to a previous report.15 Purified PMNs were resuspended in Krebs-Ringer HEPES (KRH) buffer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 6 mM glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, pH 7.4) and held on ice for no more than 3 hours prior to use. To visualize the transmigrating cells, PMNs were fluorescently labeled with a membrane-associated dye FM 1-43 (5 μg/mL) at 37°C for 20 minutes16 and were washed before use.

Studies on cultured endothelial cells

Primary cultured endothelial cells were isolated from human umbilical vein by collagenase (0.02%) digestion and were grown to confluence on a plastic dish in medium M199 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 U/mL heparin, and 25 μg/mL endothelial cell growth supplement. The endothelial monolayer was then trypsinized, resuspended in M199, and seeded on a 0.2% collagen gel-coated cover glass. The first-passage cells reached confluence within 2 days and were subsequently used in 3 or 4 days. Before the experiment, the specimens were incubated with KRH buffer overnight and immersed in 1 μM fMLP for 1 hour. The remaining immunostaining procedures were carried out in the presence of 1 μM fMLP. The specimens were labeled with primary antibodies against either VE-cadherin (1 μg/mL) or PECAM-1 (0.2 μg/mL) at 37°C for 30 minutes, washed away unbound primary antibodies, and labeled with Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies for another 30 minutes. The cover glass containing fMLP-treated, immunofluorescence-labeled specimen was mounted on a modified flow chamber that accommodated the thickness of collagen gel.17,18 Then the flow chamber was placed either on a fluorescence microscope (Diaphot 300; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) or on a confocal microscope (TCS SP2; Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) and continuously perfused with fMLP-free buffer to establish an fMLP gradient across the endothelial monolayer.18 When a PMN suspension was perfused through the chamber, PMN transendothelial migration happened shortly after their contact with the endothelial cells. Phase contrast and fluorescence images were recorded intermittently to monitor the PMN transmigration process and the accompanying movements of labeled VE-cadherin or PECAM-1 surrounding the transmigration site, respectively. All transmigration experiments were carried out at 37°C. As a comparison, certain specimens were either immunolabeled after fixation or prelabeled with only the primary antibodies and subsequently fixed and stained with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies to assure that the staining procedure in living specimens did not interfere with the PMN transmigration process.

Studies on human umbilical vein tissue segments

Freshly isolated human umbilical cords were flushed with KRH buffer and cut into 1- to 2-cm umbilical cord segments. After the umbilical vein segments were carefully dissected out, they were trimmed to remove excess adventitial tissue, longitudinally opened, and temporarily mounted on a silicon sheet. The handling process was performed without tissue dehydration. Like the cultured specimens, the tissue specimens were incubated with fMLP and immunofluorescence labeled with VE-cadherin and PECAM-1 antibodies. Finally, the specimens were mounted on a tissue flow chamber that was designed to monitor endothelial calcium signaling.19 Perfusion of the fMLP-free buffer through this tissue flow chamber also created an fMLP gradient that allowed transmigration of PMNs through the vascular endothelium. At the end of certain experiments, specimens were fixed and further processed for the scanning electron microscopic observation of transmigration sites that had been dynamically recorded under a light microscope.

Results

Immunostaining of VE-cadherin or PECAM-1 during transmigration of PMN through a monolayer of cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells

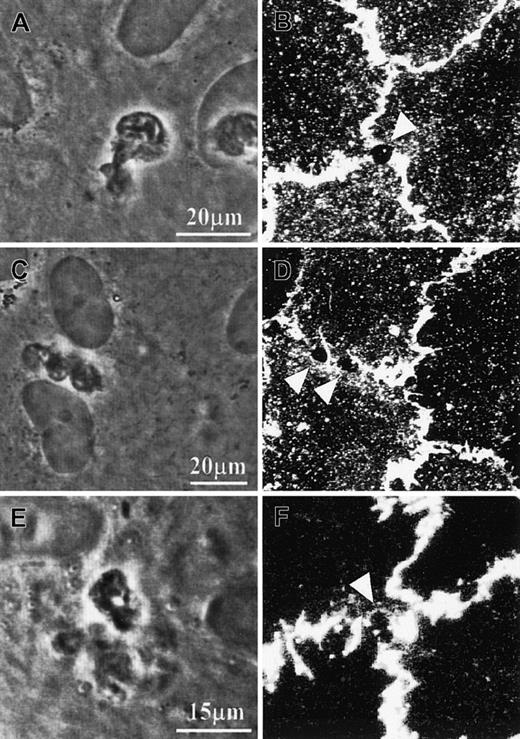

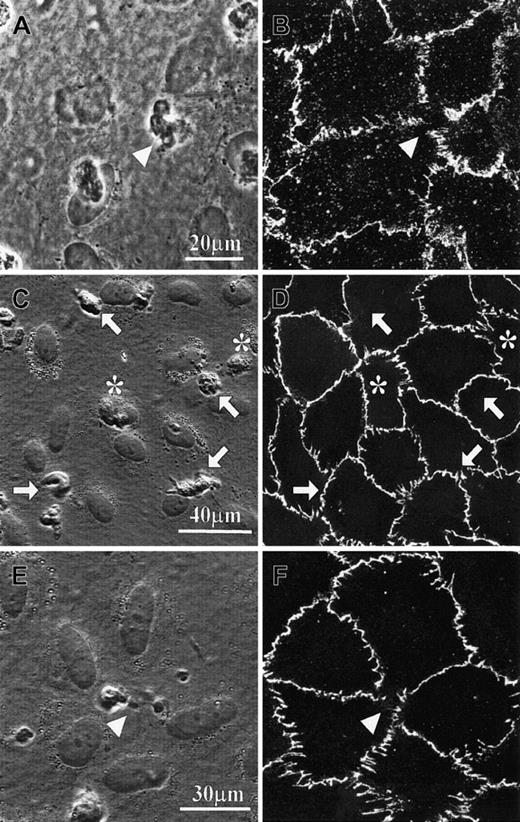

With the use of the fMLP-pretreated specimen containing an endothelial monolayer cultured on a collagen gel, we confirmed that individual PMNs in contact with the endothelial cells underwent rapid transmigration.18 After the transendothelial migration process had been traced under phase contrast optics, the specimens were fixed and immunofluorescently stained for VE-cadherin or PECAM-1 (Figures 1A-B and 2A-D). Either junction protein appeared as grossly continuous lines or belts along the interendothelial boundaries, except at PMN transmigration sites where the VE-cadherin label apparently disappeared (Figure 1B) and the PECAM-1 label became circles surrounding stain-free areas (Figure2B,D). We then tested whether prelabeling of cultured endothelial monolayer by primary antibodies against these junction proteins would affect either the subsequent PMN transmigration process or the transmigration-associated staining pattern changes (Figures 1C-F and 2E-F). After the PMN transendothelial migration process had been identified under phase contrast optics, the cultured specimens were fixed and further processed for fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies. The staining patterns of these prelabeled specimens were similar to those of prefixed specimens. Moreover, disturbed staining patterns of either junction protein were observed only in areas corresponding to transmigrating PMNs, not attached nor transmigrated PMNs.

VE-cadherin distribution on cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in the presence of PMN transmigration.

(A-B) Specimens were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in the presence of 0.5% Triton-X 100 and subsequently immunostained with anti–VE-cadherin antibody and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody. (C-F) Specimens were prelabeled with the primary antibody against VE-cadherin, fixed, and finally labeled with the secondary antibody. Confocal fluorescence micrographs B, D, and F were taken from the same specimens from which phase-contrast micrographs A, C, and E were taken. Triangle symbols indicate the locations of transmigrating PMNs. PMNs on top of the endothelial cells are marked by arrows, and PMNs already transmigrated are marked by asterisks.

VE-cadherin distribution on cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in the presence of PMN transmigration.

(A-B) Specimens were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in the presence of 0.5% Triton-X 100 and subsequently immunostained with anti–VE-cadherin antibody and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody. (C-F) Specimens were prelabeled with the primary antibody against VE-cadherin, fixed, and finally labeled with the secondary antibody. Confocal fluorescence micrographs B, D, and F were taken from the same specimens from which phase-contrast micrographs A, C, and E were taken. Triangle symbols indicate the locations of transmigrating PMNs. PMNs on top of the endothelial cells are marked by arrows, and PMNs already transmigrated are marked by asterisks.

PECAM-1 distribution on cultured HUVECs during PMN transmigration.

(A-D) Specimens were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in the presence of 0.5% Triton-X 100 and subsequently immunostained with anti–PECAM-1 antibody and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody. (E,F) Specimens were prelabeled with the primary antibody against PECAM-1, fixed, and finally labeled with secondary antibody. Confocal fluorescence micrographs B, D, and F were taken from the same specimens from which phase-contrast micrographs A, C, and E, respectively, were taken. Triangle symbols point at the stain-free areas, which correspond to the PMNs' pseudopodia that were penetrating the endothelial monolayer. Note: 2 pseudopodia from the same PMN might simultaneously penetrate the endothelial monolayer (C-D).

PECAM-1 distribution on cultured HUVECs during PMN transmigration.

(A-D) Specimens were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in the presence of 0.5% Triton-X 100 and subsequently immunostained with anti–PECAM-1 antibody and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody. (E,F) Specimens were prelabeled with the primary antibody against PECAM-1, fixed, and finally labeled with secondary antibody. Confocal fluorescence micrographs B, D, and F were taken from the same specimens from which phase-contrast micrographs A, C, and E, respectively, were taken. Triangle symbols point at the stain-free areas, which correspond to the PMNs' pseudopodia that were penetrating the endothelial monolayer. Note: 2 pseudopodia from the same PMN might simultaneously penetrate the endothelial monolayer (C-D).

Junction protein movements during PMN transmigration across a monolayer of cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells

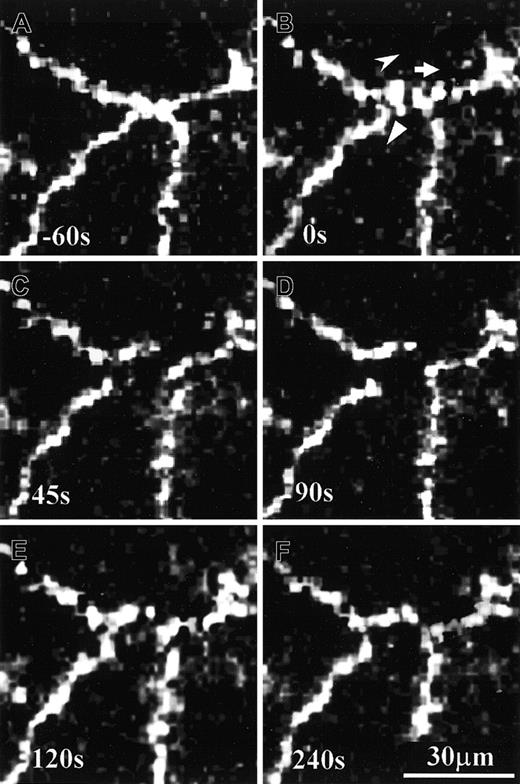

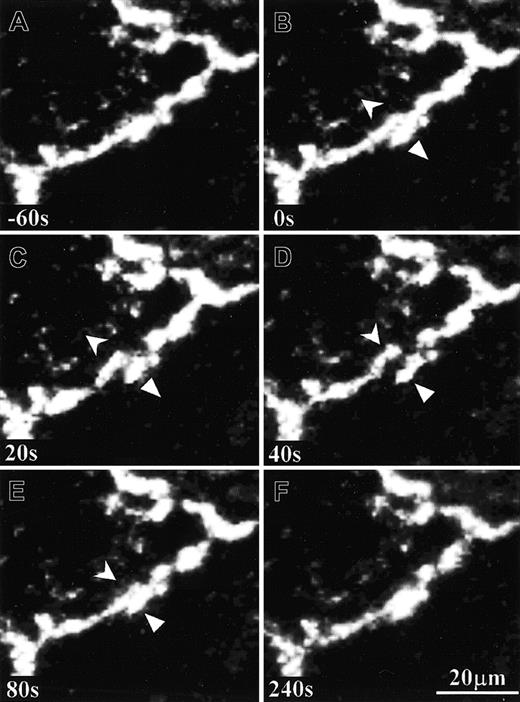

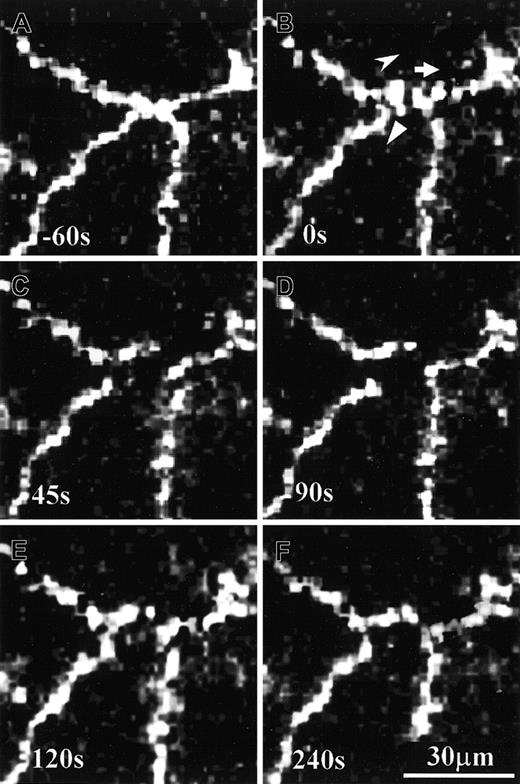

To trace the time sequence of junction protein movements during PMN transmigration, one must carry out the complete immunostaining processes before PMN arrival (ie, prelabeling of both primary and secondary antibodies in living endothelial cells). Our staining procedure was successful and apparently did not affect the PMN transendothelial migration (please see below). The exact time and location of PMN transmigration were identified under phase contrast optics (pictures not shown), whereas the dynamic behavior of junction proteins were followed under fluorescence optics. In our culture system, about 15% of the PMNs transmigrated through small gap regions (usually < 2 μm) that were free from immunostained junction proteins. The rest of PMN transmigration events were accompanied with dynamic movements of VE-cadherin (87%) or PECAM-1 (81%). During the initial stage of PMN transmigration, the VE-cadherin clusters nearby the transmigration site moved away from one another in different directions and created a VE-cadherin–free area (Figure3). This VE-cadherin–free area coincided with the transmigration site. During the later stage of PMN transmigration, VE-cadherin clusters moved back to make a continuous interendothelial boundary. The entire sequence of events usually took less than 2 minutes. As PMNs preferentially migrated through multicellular corners, the resealed boundaries as marked by VE-cadherin staining were often modified. As a comparison, the immunostained PECAM-1 structural complexes usually opened sideways to allow PMN transmigration and they resealed afterward (Figure4). When the transmigration site was located between 2 adjacent endothelial cells, the resealed interendothelial boundary resembled that of the pretransmigration state.

Time sequence of VE-cadherin movements on cultured HUVECs during PMN transmigration.

At time 0 seconds (B) a PMN started transmigrating through a monolayer of living HUVEC specimen that was previously immunostained with anti–VE-cadherin antibody and Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibody. VE-cadherin clusters moved intermittently to create a stain-free area that corresponded to the location of PMN transmigration. Three different symbols point at the momentary moving directions of 3 VE-cadherin clusters (B). This PMN transmigration process was completed in about 120 seconds, and the resealed tricellular corner was about 10 μm left to its original location (compare panels A and F).

Time sequence of VE-cadherin movements on cultured HUVECs during PMN transmigration.

At time 0 seconds (B) a PMN started transmigrating through a monolayer of living HUVEC specimen that was previously immunostained with anti–VE-cadherin antibody and Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibody. VE-cadherin clusters moved intermittently to create a stain-free area that corresponded to the location of PMN transmigration. Three different symbols point at the momentary moving directions of 3 VE-cadherin clusters (B). This PMN transmigration process was completed in about 120 seconds, and the resealed tricellular corner was about 10 μm left to its original location (compare panels A and F).

Time sequence of PECAM-1 movement on cultured HUVECs during PMN transmigration.

A PMN was transmigrating through a monolayer of living HUVEC specimen that was previously immunostained with anti–PECAM-1 antibody and Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibody. Symbols indicate the momentary moving directions of 2 adjacent PECAM-1 clusters (B-E). This PMN transmigration process was completed in about 80 seconds, and the resealed bicellular boundary was restored almost to its original state (compare panels A and F).

Time sequence of PECAM-1 movement on cultured HUVECs during PMN transmigration.

A PMN was transmigrating through a monolayer of living HUVEC specimen that was previously immunostained with anti–PECAM-1 antibody and Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibody. Symbols indicate the momentary moving directions of 2 adjacent PECAM-1 clusters (B-E). This PMN transmigration process was completed in about 80 seconds, and the resealed bicellular boundary was restored almost to its original state (compare panels A and F).

Junction protein movements during PMN transmigration across the human umbilical vein endothelium

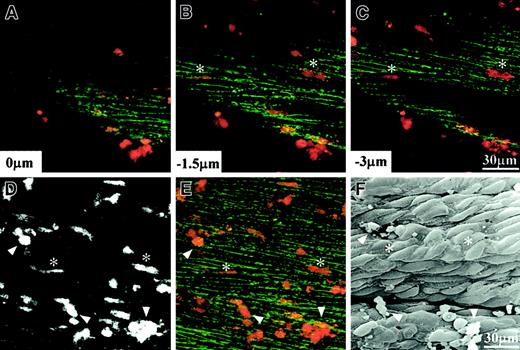

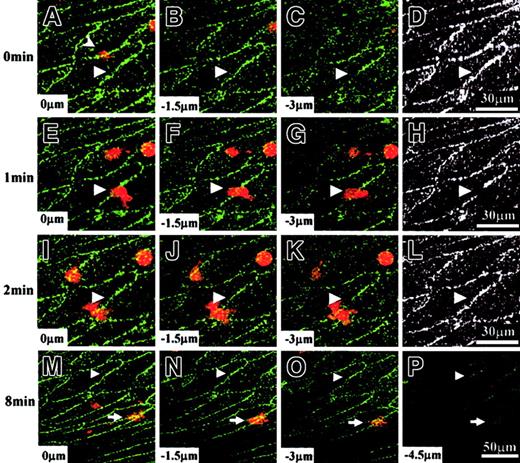

Because it was difficult to examine the tissue specimens under phase contrast optics, PMNs used in the following experiments were prelabeled with the fluorescent dye FM 1-43 to observe their transmigration under a confocal microscope. By using a dissected umbilical venous segment that was pretreated with fMLP and immunostained for VE-cadherin, we found that individual PMNs in contact with the endothelial cells also underwent rapid transmigration (Figure5). Results from confocal light microscopic observation of living tissue specimens were confirmed by mapping the transmigration sites from the corresponding scanning electron micrograph. Attached PMNs were found on the vascular endothelium by either method, but transmigrated PMNs identified from confocal images were absent in the corresponding scanning electron micrograph.

Transendothelial migration of PMNs on human umbilical vein tissue.

(A-E) Living confocal images with PMNs stained with FM 1-43 (red) and endothelial VE-cadherin immunostained with Alexa Fluor 488 (green), whereas panel F shows a scanning electron micrograph of the same specimen after fixation. (A-C) Individual optical sections obtained from different depths; (D) a depth-combined image of FM 1-43; (E) a depth-combined image of both FM 1-43 and Alexa Fluor 488. Among numerous PMNs shown here, 2 transmigrated PMNs are indicated by asterisks, and 3 adhered PMNs are indicated by triangles.

Transendothelial migration of PMNs on human umbilical vein tissue.

(A-E) Living confocal images with PMNs stained with FM 1-43 (red) and endothelial VE-cadherin immunostained with Alexa Fluor 488 (green), whereas panel F shows a scanning electron micrograph of the same specimen after fixation. (A-C) Individual optical sections obtained from different depths; (D) a depth-combined image of FM 1-43; (E) a depth-combined image of both FM 1-43 and Alexa Fluor 488. Among numerous PMNs shown here, 2 transmigrated PMNs are indicated by asterisks, and 3 adhered PMNs are indicated by triangles.

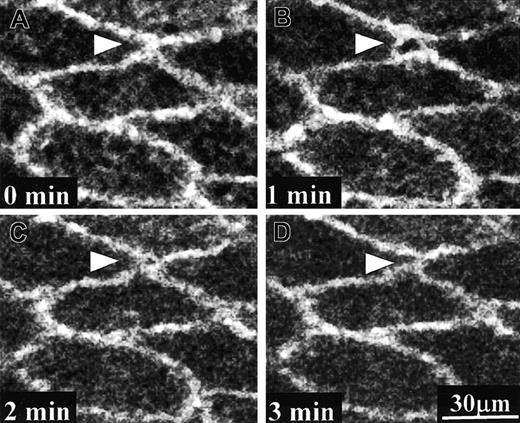

In the tissue system, about 25% of the PMNs transmigrated through small gap regions (usually < 2 μm) that were free from immunostained junction proteins. The rest of PMN transmigration events were accompanied with dynamic movements of VE-cadherin (74%) or PECAM-1 (72%). The sequence of events during PMN transendothelial migration on human umbilical venous tissue was traced from confocal images. The time courses as well as the junction protein movement patterns for either VE-cadherin (Figure6) or PECAM-1 (Figure7) were similar to those observed in the culture system. Figure 6 shows an example that the VE-cadherin structural complexes originally distributed along the interendothelial boundary became pushed aside to proximal ends of the transmigration site when a PMN was transmigrating between 2 endothelial cells. As a comparison, PECAM-1 molecules underwent the dissociation-reassociation type of movements either in tissue (Figure7) or in culture (Figure 4). It was interesting to note that, although many transmigrated PMNs in the vascular tissue rapidly moved away from their original transmigration sites (up to 15 μm/minute) according to real-time tracings, their final locations were always closely underneath the endothelium at the end of a 20-minute experiment (Figure 6M-P). This finding contrasts to the results obtained from using our cultured cell model system in which transmigrated PMNs rapidly penetrated into the collagen gel. Transmigrated PMNs were capable of moving more than 50 μm deep into the collagen gel within 15 minutes, and they usually became out of focus under phase contrast observation shortly after the transendothelial migration process was completed (picture not shown).

Time sequence of VE-cadherin movement on human umbilical vein tissue during PMN transmigration.

A PMN (stained with FM 1-43, red) was transmigrating through living human umbilical vein tissue that was previously immunostained with VE-cadherin antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, green). The PMN transmigration site (triangle) was located at the boundary between 2 adjacent endothelial cells. This PMN was originally located on top of the vascular endothelium at 0 minute and displayed as a faint red image in panel A (arrowhead). It was already underneath the vascular endothelium at 2 minutes (I-K). (D,H,L) These panels are black-and-white pictures from depth-combined VE-cadherin images obtained at 0 minute, 1 minute, and 2 minutes, respectively. VE-cadherin clusters surrounding the transmigration site moved to opposite ends at 1 minute (E-H) and moved back to their original locations at 2 minutes (I-L). When this PMN transmigration process was completed, the resealed bicellular boundary was essentially the same as before (compare D and L). After transendothelial migration, this PMN moved laterally underneath the vascular endothelium without penetrating deeply into the smooth muscle layers. Its location (arrow) was about 80 μm away from the transmigration site at 8 minutes (M-P).

Time sequence of VE-cadherin movement on human umbilical vein tissue during PMN transmigration.

A PMN (stained with FM 1-43, red) was transmigrating through living human umbilical vein tissue that was previously immunostained with VE-cadherin antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, green). The PMN transmigration site (triangle) was located at the boundary between 2 adjacent endothelial cells. This PMN was originally located on top of the vascular endothelium at 0 minute and displayed as a faint red image in panel A (arrowhead). It was already underneath the vascular endothelium at 2 minutes (I-K). (D,H,L) These panels are black-and-white pictures from depth-combined VE-cadherin images obtained at 0 minute, 1 minute, and 2 minutes, respectively. VE-cadherin clusters surrounding the transmigration site moved to opposite ends at 1 minute (E-H) and moved back to their original locations at 2 minutes (I-L). When this PMN transmigration process was completed, the resealed bicellular boundary was essentially the same as before (compare D and L). After transendothelial migration, this PMN moved laterally underneath the vascular endothelium without penetrating deeply into the smooth muscle layers. Its location (arrow) was about 80 μm away from the transmigration site at 8 minutes (M-P).

Time sequence of PECAM-1 movement on human umbilical vein tissue during PMN transmigration.

A PMN (stained with FM 1-43, located within the framed area) was transmigrating through the endothelium of human umbilical vein tissue that was previously immunostained with PECAM-1 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488). For picture clarity, only Alexa Fluor 488 images are displayed here. Different panels showed the depth-combined confocal images of PECAM-1 obtained at different times as indicated. PECAM-1 molecules around the transmigration site moved away from one another to leave an opening at 1 minute and almost resealed at 2 minutes. By the end of this PMN transmigration process the interendothelial boundary restored almost to the original state.

Time sequence of PECAM-1 movement on human umbilical vein tissue during PMN transmigration.

A PMN (stained with FM 1-43, located within the framed area) was transmigrating through the endothelium of human umbilical vein tissue that was previously immunostained with PECAM-1 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488). For picture clarity, only Alexa Fluor 488 images are displayed here. Different panels showed the depth-combined confocal images of PECAM-1 obtained at different times as indicated. PECAM-1 molecules around the transmigration site moved away from one another to leave an opening at 1 minute and almost resealed at 2 minutes. By the end of this PMN transmigration process the interendothelial boundary restored almost to the original state.

The dynamic results are summarized in Table1. It was clear that the transmigration time was about the same regardless where the PMN transmigration site was located. Moreover, both types of junction proteins closed up almost immediately after the transmigration process was completed. Although the transmigration process in tissue seemed to take longer times than that in culture, this discrepancy was largely due to relatively poor time resolution in tissue experiments; ie, it took 1 minute to obtain a set of optical sections from a tissue specimen.

Discussion

By applying immunofluorescence-staining methods to living specimens, we traced the dynamic movements of 2 junction proteins, VE-cadherin and PECAM-1, during the fMLP gradient-induced transmigration of PMNs either through a cultured endothelial cell monolayer or through the endothelium of a dissected vascular tissue. Although both junction proteins relocated to allow PMN passage, their dynamic movement patterns were entirely different. Detailed observations in numerous cases supported the notion that VE-cadherin linkages were pushed aside to leave a linkage-free region for PMN transmigration. In contrast, interendothelial PECAM-1 linkages were disrupted around the transmigration site. Nevertheless, both junction proteins resealed immediately after the completion of the transmigration process.

There were several advantages in our systems. First, the dynamic behavior of 2 functionally different junction proteins during single PMN transmigration was monitored. Second, in addition to using a cultured system, we also examined in parallel a vascular tissue system under flow that resembled in vivo conditions. Third, endothelium-stimulating agents used in other studies, such as tissue necrosis factor-α6-8,13,14 or platelet-activating factor,11 12 were absent in our systems and thus avoided the possible disturbances to the endothelial junction proteins prior to PMN transmigration. Finally, the possible artifacts related to postfixation release of proteases from PMNs were avoided.

By using a tissue flow chamber system, we confirmed most results obtained from using the culture system. They are as follows: (1) PMN transendothelial migration was a rapid process that preferentially happened at multicellular corners14,18,20; (2) it was accompanied with differential movements of VE-cadherin14(the present study) and PECAM-1 (the present study); (3) these junction proteins resealed after the transmigration process was completed14,21; and (4) paracellular diapedesis, but not transcellular diapedesis, was observed.14 20

Within our spatial resolution limit, all PMN transmigration events happened at the periphery of endothelial cells. Moreover, all observed transmigration events were accompanied with relocation of junction proteins. Although the possibility of transcellular transmigration of PMNs could not be ruled out completely, we have not seen any PMNs transmigrated through the central portion of the endothelial cell body, either in culture or in tissue. It has been reported that in response to fMLP, PMNs emigrate from cutaneous venules by a transcellular route through both endothelial cells and pericytes.22 Perhaps the transcellular pathway is mainly applied to PMN transmigration through highly permeable vascular tissues.

Our study also showed that, although PMNs were rather mobile after the completion of transendothelial migration, they remained close to the endothelium in tissue. Previously, we have shown that transmigrated PMNs in the culture system pause briefly and became flattened before they further penetrate into the collagen gel.18 Apparently the vascular structures underneath the endothelium prevented the transmigrated PMNs from migrating into deeper tissue layers. In contrast, posttransmigrational PMN movements were not hindered by the adhesive interactions between endothelium and subendothelium materials. How PMNs become trapped underneath the endothelium and yet still maintain their lateral mobility are interesting issues. It is well known that transendothelial-migrated monocytes became foam cells trapped in the atherosclerotic vascular intima. Perhaps other leukocytes, such as monocytes, would be selectively retained in the intima for similar reasons as well.

Our VE-cadherin immunostaining results using culture system nicely confirmed a recent report tracing the movements of VE-cadherin/green fluorescence fusion protein construct during PMN transmigration through a cultured endothelial cell monolayer.14 These 2 approaches are basically complementary to each other. Although the fusion protein expression system presumably would not interfere with the extracellular, homophilic interacting component of VE-cadherin molecules, the immunostaining procedure would only tag the endogenous, membrane-bound VE-cadherin molecules. Results from both studies support the hypothesis that endothelial VE-cadherin molecules near the transmigrating PMNs become pushed aside and move back afterward (ie, the so-called curtain effect). Neither study showed any evidence supporting the disruption of VE-cadherin complexes. Moreover, if the PMN transmigration process required the cleavage of extracellular domain of VE-cadherin by proteases, the immunostaining of endogenous VE-cadherin surrounding the transmigration sites would have been lost after PMN passage. Although PMN transmigration may require protease activation in other inflammation model systems,11,12 our results do not favor such a mechanism for junction protein movements. Perhaps proteases play some novel roles in steps either before or after the PMN transmigration process and thus exert indirect influences on it via affecting the overall transmigration efficiency. Finally, the immunostaining procedure apparently did not affect the time course of PMN transmigration, which was almost the same as that in the unlabeled specimens18,23 (ie, averaging less than 1.5 minutes for the entire process). In comparison, the VE-cadherin molecules fused with green-fluorescence protein would take 5 minutes in average to accomplish the resealing step alone (from 2 to 11 minutes).14 Although overexpression of this fusion protein construct enhances the endothelial barrier function to macromolecules in the culture system,14 whether a prolonged resealing process after PMN transmigration would give rise to extra leakage across the endothelial monolayer has not been reported.

One possible explanation for the differential movements between VE-cadherin and PECAM-1 is that, although both junction proteins reside at interendothelial boundaries, the latter is also present on the surface of transmigrating leukocytes. It has been proposed that the PECAM-PECAM linkages between endothelial cells and the transmigrating PMNs transiently replaced similar homophilic linkages between adjacent endothelial cells during PMN diapedesis.2,5 If this were true, the disruption of existing PECAM-PECAM linkages between adjacent endothelial cells must happen. Because PECAM-1 belongs to a family of molecules that contain one or more immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs within their cytoplasmic domain,24 the transient disruption of existing linkage between these molecules could send activation signals into the endothelial cells.

It has been reported that the endothelial intracellular calcium signaling is required for PMN transendothelial migration.23 Moreover, this signaling process is a local event that happens only in endothelial cells surrounding the transmigrating PMNs.18 One of the downstream targets for calcium signaling is the activation of myosin light chain (MLC) kinase via the calcium/calmodulin pathway. Stimulated PMNs can induce endothelial MLC phosphorylation, and inhibitors of calmodulin or MLC kinase can block the PMN transendothelial migration.25,26It is plausible to assume that PMN transmigration requires the endothelium to play an active role, such as pulling away or dissociating junction complexes via endothelial signaling pathway activation. However, the VE-cadherin experiments pointed out another possibility that junction proteins apparently become pushed away by the squeezing forces generated by the transmigrating PMNs14(the current study). If the latter were true, then the target of endothelial activation would certainly need further identification.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 25, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0303.

Supported by grants NSC 90-2320-B-006-047, 90-2320-B-006-077, and MOE 91-B-FA09-2-4 from The National Science Council and The Ministry of Education, Taiwan, Republic of China.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Chauying J. Jen, Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, National Cheng-Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan, R.O.C.; e-mail: jen@mail.ncku.edu.tw.