We investigated the feasibility of unrelated stem cell transplantation in 21 patients with advanced stage II/III multiple myeloma after a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen consisting of fludarabine (150 mg/m2), melphalan (100-140 mg/m2), and antithymocyte globulin (ATG; 10 mg/kg on 3 days). The median patient age was 50 years (range, 32-61 years). All patients had received at least one prior autologous transplantation, in 9 cases as part of an autologous-allogeneic tandem protocol. No graft failure was observed. At day 40 complete donor chimerism was detected in all patients. Grade II to IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was seen in 8 patients (38%), and severe grade III/IV GVHD was observed in 4 patients (19%). Six patients (37%) developed chronic GVHD, but only 2 patients (12%) experienced extensive chronic GVHD. The estimated probability of nonrelapse mortality at day 100 was 10% and at 1 year was 26%. After allografting, 40% of the patients achieved a complete remission, and 50% achieved a partial remission, resulting in an overall response rate of 90%. After a median follow-up of 13 months, the 2-year estimated overall and progression-free survival rates are 74% (95% CI, 54%-94%) and 53% (95% CI, 29%-87%), respectively. A shorter progression-free survival was seen in patients who already experienced relapse to prior autograft (26% versus 86%, P = .04). Dose-reduced conditioning with pretransplantation ATG followed by unrelated stem cell transplantation provides durable engraftment and donor chimerism, reduces substantially the risk of transplant-related organ toxicity, and induces high remission rates.

Introduction

After allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) from HLA-identical related donors, 30% to 50% of the patients with multiple myeloma (MM) had long-term disease-free survival with well-documented molecular remissions.1-4 There is a lower relapse rate in comparison to autologous transplantation, which is probably due to a proven graft-versus-myeloma effect.5-7 Despite recent better control of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and of infectious complications, the most limiting factor for allogeneic SCT is still the high transplant-related mortality rate of 17% to 40%.8,9Unrelated SCT is increasingly being used in hematologic diseases such as chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) with outcomes quite similar to those of HLA-identical sibling donor transplantation.10 However, the limited experience with unrelated SCT following standard conditioning regimens in patients with MM are discouraging. Recently, the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) reported a day 100 mortality rate of 41% in 71 myeloma patients who underwent allogeneic unrelated SCT, and the Seattle group reported a transplant-related mortality rate of 65% in 14 myeloma patients who received transplants from unrelated or mismatched related donors.11 12 However, in the latter study 2 of the surviving patients are disease-free up to 7 years after transplantation. These results emphasize the urgent need for strategies to lower transplant-related mortality in patients with MM after unrelated SCT.

So-called nonmyeloablative regimens based on fludarabine or low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) demonstrated stable engraftment of allogeneic stem cells from related donors in patients with hematologic diseases including MM.13-16 However, in unrelated SCT after a reduced-intensity melphalan/fludarabine conditioning regimen the nonrelapse mortality (NRM) at day 100 was still 53% mainly due to severe GVHD.17 We report the results of a multicenter phase I/II study investigating the feasibility of a fludarabine-melphalan dose-reduced intensity regimen followed by unrelated SCT in patients with advanced MM. To lower the incidence of severe GVHD, antithymocyte globulin (ATG), which has been used successfully in unrelated transplantation after standard conditioning regimens, was incorporated into the conditioning regimen.17-21

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

Patients with advanced MM were enrolled at 4 German and 1 Israeli transplantation center. At each participating center, the study was approved by the local ethics committee. Written informed consent was received from each patient. Patients with advanced MM stage II/III, aged 18 to 65 years, with response or refractory to induction or salvage chemotherapy were eligible for the study protocol. Nine patients were treated in a sequential autologous-allogeneic tandem approach and 12 patients received an allograft after relapse or no change following an autologous transplantation. To be included patients were required to have sufficient cardiac function (ejection fraction > 30%), a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/h, a lung diffusion capacity of at least 50%, and liver transaminase values not more than 3 times the upper limit of normal. HLA-A and HLA-B antigens were typed by serologic methods; HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 alleles were typed with sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes. One antigen mismatch in class I or II was allowed. Unrelated donors gave informed consent according to the national protocol and stem cell mobilization/collection or bone marrow harvesting was performed according to the accepted international and national standards and procedures.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in detail in Table1. Twenty-one patients were enrolled in the study between January 2000 and January 2002. Preliminary results in 7 patients who were treated in an autologous-allogeneic tandem protocol have been reported in a previous report and are now included with an extended follow-up.22

The median age of the 13 men and 8 women was 50 years (range, 32-61 years). Ten donors were men and 11 were women. The median β2-microglobulin level at diagnosis was 2.9 mg/dL (range, 1.0-7.0 mg/dL). Cytogenetic fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was available in 6 patients and showed a deletion 13 in one patient. Nine patients had received prior radiation therapy and the median number of previous chemotherapy cycles was 6 (range, 4-15). All patients had received at least one previous cycle of high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous SCT. Seven patients had received 2 cycles of previous high-dose chemotherapy. Eleven patients experienced relapse after autologous transplantation, whereas 10 patients received an allogeneic transplant as consolidation therapy after an autograft, either as a planned autologous-allogeneic protocol (n = 9) or after no change to an autograft (n = 1). The disease status prior to allogeneic transplantation was complete remission (CR; n = 1), partial remission (PR; n = 8), minor response (MR; n = 1), no change (NC; n = 3), and progressive disease (PD; n = 8). Nineteen patients were matched for class I and II alleles, whereas 2 were mismatched in HLA-A and DRB1, respectively. The median time from diagnosis to transplantation was 33 months (range, 9-103 months). The serostatus of cytomegalovirus (CMV) of the recipient and the donor prior to transplantation was positive/positive in 9, positive/negative in 2, negative/negative in 8, and negative/positive in 2 cases. The source of stem cells was peripheral blood in 16 patients and bone marrow in 5 patients. No manipulation of the graft was performed.

Treatment plan

Treatment consisted of fludarabine 30 mg/m2 by intravenous infusion over 30 minutes on day −7 to −3 and melphalan by intravenous infusion of 100 mg/m2 on day −2. ATG (rabbit, Fresenius, Bad Homburg, Germany) was given at a dose of 10 mg/kg over 12 hours on day −3, −2, and −1, followed by allogeneic SCT on day 0. Six patients received fludarabine 30 mg/m2 only from day −5 to −3; 5 patients received melphalan 140 mg/m2. Because of 2 grade IV acute GVHD, the following patients (n = 4) received ATG at a dose of 3 × 20 mg/kg. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF; 5 μg/kg) was given intravenously after allogeneic transplantation from day 5 and continued until sustained neutrophil engraftment. In case of relapse, incomplete chimerism, or persistent disease on day 120 additional donor lymphocyte infusions were scheduled with an escalating regimen starting with 1 × 106 CD3+ cells/kg.

Supportive care

Prophylaxis for GVHD consisted of cyclosporin A (3 mg/kg, given from day −1 to day +100 after transplantation). The dose of cyclosporin A was adjusted to serum levels. Cyclosporin A was tapered from day 60 and discontinued at day 100 if no signs of GVHD were observed. Methotrexate (10 mg/m2) was given on days 1, 3, and 6 after transplantation. Two patients received mycophenolate mofetil (2 × 1 g from day +1 until day +28) instead of short-course methotrexate. Acute GVHD was treated with high-dose steroids, and extensive chronic GVHD with cyclosporin A and steroids. All patients were nursed in single rooms equipped with a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter. Antibiotic prophylaxis consisted of ofloxacin or ciprofloxacin and antifungal prophylaxis of fluconazole and, in case of prior mycotic infection, of amphotericin B. Acyclovir was given as herpes prophylaxis from day 1 until day 180. CMV seropositive patients received CMV prophylaxis with ganciclovir from stable engraftment onward until day 100. Pneumocystis cariniiprophylaxis consisted of either trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole on 3 days of the week or of a monthly inhalation with pentamidine.

All blood products were irradiated before infusion and patients with seronegativity for CMV received only blood products from CMV− donors.

Weekly monitoring of blood and urine for CMV antigen by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and short-term cultures of CMV lower matrix protein pp65+ leukocytes were carried out. In case of positivity, ganciclovir treatment was initiated (5 mg/kg body weight intravenously, twice daily) and discontinued after negative test results were obtained.

Regimen-related toxicity was graded using the Bearman score.23 The maximum score for each organ system was recorded. Attempts were made to exclude toxicities due to GVHD from the therapy-related toxicity.

Study objective

The primary objective of the study was to assess engraftment, chimerism, acute GVHD, toxicity, day 100 mortality, and chronic GVHD in patients undergoing unrelated SCT. Engraftment was defined as a leukocyte count of more than 1 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days and an untransfused platelet count above 20 × 109/L. Chimerism analysis was performed by allele-specific multiplex PCR technique. DNA was prepared from 200 μL blood and bone marrow using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. T cells were obtained using CD2 MicroBeads and miniMACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). A mixed chimerism was defined as the presence of at least 5% recipient DNA.

The standard criteria were used for grading of acute and chronic GVHD.24 Chronic GVHD was evaluated in patients who survived at least 100 days with sustained engraftment.

The secondary objective was to evaluate the response rate. Response to treatment was defined according to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation/International Bone Marrow Transplantation Registry (IBMTR) criteria.25 Briefly, complete remission (CR) required a disappearance of monoclonal gammopathy in serum and urine as determined by immunofixation analysis for at least 6 weeks and less than 5% plasma cells in a bone marrow aspirate. A partial remission (PR) was defined as more than 50% reduction and a minor response (MR) as more than 25% reduction of the paraprotein level, respectively. No change (NC) was defined as a less than 25% decrease or increase of the paraprotein. Relapse was defined as recurrence of the monoclonal protein or bone marrow plasmocytosis in case of prior CR. Progression of non-CR patients required at least a 25% increase of paraprotein or development of new bone lesions.

Statistical methods

Survival curves for disease-free survival and overall survival were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was performed for statistical analysis for time-dependent analyses of survival, relapse, and disease-free survival. P < .05 was considered significant. Overall survival was calculated from transplantation until death from any cause. Progression-free survival was calculated from transplantation until progression or death from any cause.

Results

Toxicity

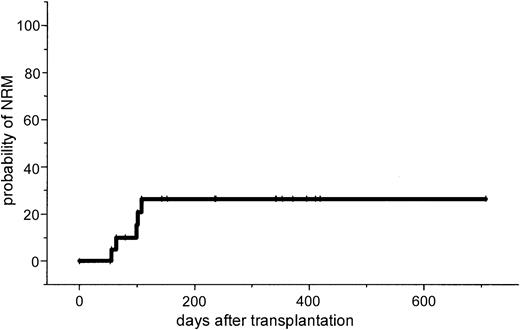

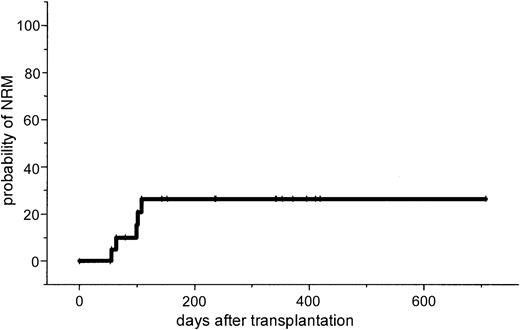

The major toxicity according to the Bearman scale was mucositis grade I in 24% and grade II in 64% of the patients. Liver toxicity grade I/II was observed in 35% of the patients and resolved completely in all cases. No veno-occlusive disease was observed. Two patients developed grade II lung toxicity that resolved completely after steroid treatment. Because this lung toxicity might be attributed to fludarabine, the dose of fludarabine was reduced to 3 × 30 mg/m2 and subsequently no further lung toxicity was observed. Two renal failures were observed. In one patient renal function recovered completely and the other patient (no. 21) with progressive Bence Jones proteinuria died from severe GVHD. One patient (no. 7) developed fever and enlarged para-aortal lymph nodes. Due to a high Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) load as determined by PCR, anti-CD20 treatment was initiated. Two weeks after therapy he died on day 119 after unexpected sudden cardiac arrest in CR. No autopsy was performed. Positive CMV antigenemia by pp65 test was observed in 3 patients (14%), and 2 of them were treated successfully with ganciclovir. One patient with CMV seropositivity and a negative donor showed repeated CMV antigenemia and was treated with a combination of ganciclovir and foscarnet sodium. No CMV disease was noted. Two patients died of severe acute GVHD; 1 of these had Bence Jones proteinuria and renal failure; 2 patients had infections (septicemia and cerebral aspergillosis). The estimated probability of NRM was 10% at day 100 (95% CI, 1%-19%) and 26% at 1 year (95% CI, 7%-45%).

Engraftment

The median transplanted CD34+ cell number was 3.9 × 106/kg body weight (range, 0.4-12.5 × 106/kg body weight). All patients became neutropenic (< 0.2 × 109/L) and thrombocytopenic (< 20 × 109/L) and required platelet and erythrocyte transfusions. No primary or secondary graft failure was observed. The median time until leukocyte (> 1 × 109/L) and platelet (> 20 × 109/L) engraftment was 16 days (range, 10-24 days) and 22 days (range, 11-36 days), respectively.

Chimerism

Complete donor chimerism was detected in all patients by day 40. T-cell chimerism was evaluated in 11 patients and all showed complete donor chimerism on day 40 after allogeneic transplantation.

GVHD

Five patients (24%) did not show any signs of acute GVHD. Eight patients (38%) developed mild acute GVHD grade I; grade II was noted in 4 patients (19%). Grade II to IV acute GVHD was seen in 8 patients (38%), and severe grade III/IV GVHD was observed in 4 patients (19%). Two cases of lethal grade IV GVHD were seen, 1 in a patient with HLA-mismatched transplantation and the other in a patient with refractory disease.

Chronic GVHD was evaluated in 16 patients. Ten (63%) did not show any sign of chronic GVHD. Six patients developed chronic GVHD (37%); 4 patients had limited (25%) and only 2 patients had extensive (12%) chronic GVHD.

Response

After allogeneic transplantation, 8 patients achieved a CR (40%) and 10 patients a PR (50%), resulting in an overall response rate of 90%. Two of the patients with a PR were only positive in immunofixation and an additional 4 patients show an ongoing decrease of monoclonal bands. One patient (5%) achieved only a MR and 1 patient progressed after allogeneic transplantation (5%). Six patients with PR prior to transplantation converted to CR after allografting. For 8 patients with PD prior to transplantation, 1 converted to CR, 6 to PR, and 1 remained progressive after unrelated allografting (Table2). So far, 4 patients have received donor lymphocyte infusions because of progressive (n = 3) or persistent disease (n = 1). One patient developed grade II acute GVHD and showed a MR; another patient showed neither a sign of GVHD nor of tumor reduction. It is too early to evaluate 2 patients.

Overall survival and disease-free survival

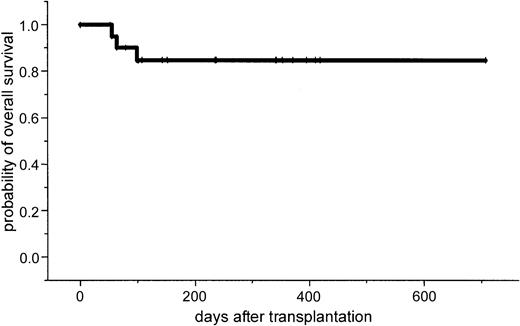

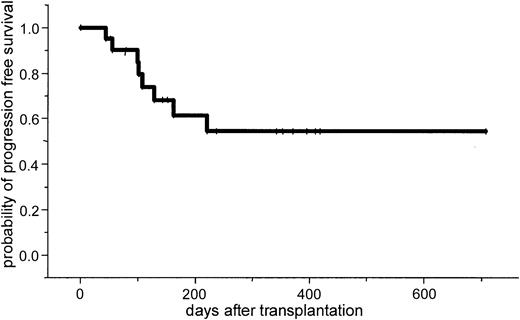

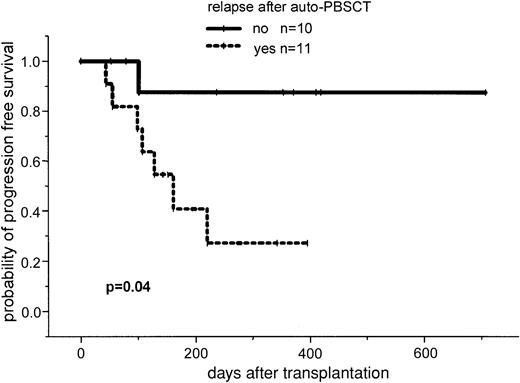

After a median follow-up of 386 days (range, 100-769 days), the 2-year estimated overall survival was 74% (95% CI, 54%-94%; Figure1). In an univariate analysis there was a trend for better overall survival for patients without relapse after autologous transplantation: 86% (95% CI, 63%-99%) versus 64% (95% CI, 39%-89%; P = .3). Further univariate analysis for overall survival did not show significant difference for age (< or > 50 years), β2-microglobulin, donor sex, remission status for prior allograft (PR/CR versus NC/MR/PD), CMV seropositivity, time to transplantation from diagnosis, stem cell source, acute and chronic GVHD, and CD34 cell dose. The 2-year estimated disease-free survival was 53% (95% CI, 29%-87%). In a univariate analysis only relapse after autologous transplantation resulted in a less favorable outcome in comparison to patients without relapse: 26% (95% CI, 3%-49%) versus 86% (95% CI, 63%-99%; P = .04; Figures2 and3).

Progression-free survival in patients with and without relapse or progression after autologous transplantation.

Progression-free survival in patients with and without relapse or progression after autologous transplantation.

Discussion

This study in patients with advanced MM demonstrates that a dose-reduced conditioning regimen with allogeneic SCT from unrelated donors is a feasible and highly effective treatment. The 2-year estimated overall survival of 74% and the disease-free survival of 53% is encouraging. However, it will require a longer follow-up period to determine the curative potential of this approach for this otherwise fatal disease. Only a few reports exist on the outcome of unrelated SCT in MM. In the largest report of the NMDP, 71 patients received an unrelated stem cell transplant after standard conditioning. A day 100 mortality rate of 41% and an estimated 5-year overall survival rate of only 17% were reported.11 Bensinger et al reported a 64% treatment-related mortality in 14 patients who received transplants from unrelated or mismatched related donors.12 To reduce treatment-related mortality after allogeneic SCT, reduced-intensity regimens based on TBI/fludarabine, busulfan/fludarabine, or melphalan/fludarabine for related and unrelated SCT have been developed.13-18 However, in unrelated SCT, GVHD and treatment-related mortality remain major problems. Giralt et al reported a day 100 mortality rate of 53% and a risk of grade II to IV acute GVHD of 62% after a melphalan/purine analog–containing reduced-intensity regimen.17 Recently, Badros et al reported data on 6 patients with advanced MM who received transplants from unrelated donors after a reduced-intensity regimen consisting of melphalan/fludarabine and low-dose TBI (2.5 Gy). They reported a day 100 mortality rate of 33% and one primary graft failure was observed.26 In our study no graft failure occurred; only 38% of the patients developed acute stage II to IV GVHD and the estimated NRM at day 100 was only 10% (Figure4).

One might ask why such differences occurred with nearly the same melphalan/fludarabine-based regimen. The major difference in the studies mentioned above is the incorporation of ATG into the conditioning regimen in our study. A similar incidence of acute grade II to IV GVHD (43%) was reported for dose-reduced conditioning followed by unrelated SCT by Nagler et al, who also used ATG as part of the conditioning regimen consisting of busulfan and fludarabine.27 The ATG used in both studies was from rabbits (Fresenius-ATG). This in vivo depletion of activated T cells in the recipient might facilitate engraftment, and due to the long half-life of the immunoglobulin, an additional in vivo T-cell depletion of the graft might reduce the incidence of GVHD. Therefore, ATG as part of the conditioning regimen has been used successfully in unrelated SCT to ensure engraftment and to reduce the incidence of severe GVHD.18-21 The major concern of any form of T-cell depletion is the high incidence of relapse.28 Attempts to overcome this high incidence of relapse by donor lymphocyte infusions were associated with a high incidence of acute and chronic GVHD.29,30 In contrast to other forms of T-cell depletion or other ATG preparations, the ATG used in our study does not lead to a significant increase of relapse in unrelated and related SCT.31-33 Besides the ATG, other forms of serotherapy have been described in allogeneic SCT. Recently, stable engraftment after a dose-reduced melphalan/fludarabine regimen incorporating pretransplantation alemtuzumab (CAMPATH 1H), a humanized anti-CD52 antibody, has been described.34 In that study only 21% of the patients developed grade II to IV acute GVHD, but after donor lymphocyte infusion, which was given to 6 patients mainly to enhance remission status or donor chimerism, 50% developed grade II/III acute GVHD.

Previous studies of allografting from related donors after standard conditioning clearly showed that early transplantation in the course of disease improves outcome.1,2 12 In our study, we demonstrated that there was a significant better progression-free survival for those patients who received a transplant without prior failure of autologous transplantation. Other factors such as age, time to transplantation, response prior to transplantation, or β2-microglobulin did not significantly influence outcome, but this could be due to the limited number of patients and the short follow-up. We conclude that the reduced-conditioning regimen with melphalan/fludarabine along with pretransplantation ATG followed by unrelated SCT provides rapid and sustained engraftment with durable complete donor chimerism and low day +100 treatment-related mortality. Longer follow-up in a larger group of patients is needed to determine the late relapse and the curative potential. Because of the better outcome in patients without prior failure to autograft, allogeneic SCT from unrelated donors should be investigated at an earlier phase of the disease.

We thank the staff of the Bone Marrow Transplantation units for providing excellent care of our patients and the medical technicians for their excellent work in the Bone Marrow Transplantation laboratories.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 8, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1150.

Supported by a grant from the Roggenbuck-Stiftung.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Nicolaus Kröger, The Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr 52, D-20246 Hamburg, Germany; e-mail:nkroeger@uke.uni-hamburg.de.