Abstract

Tumor cells are usually weakly immunogenic as they largely express self-antigens and can down-regulate major histocompatability complex/peptide molecules and critical costimulatory ligands. The challenge for immunotherapies has been to provide vigorous immune effector cells that circumvent these tumor escape mechanisms and eradicate established tumors. One promising approach is to engineer T cells with single-chain antibody receptors, and since T cells require 2 distinct signals for optimal activation, we have compared the therapeutic efficacy of erbB2-reactive chimeric receptors that contain either T-cell receptor zeta (TCR-ζ) or CD28/TCR-ζ signaling domains. We have demonstrated that primary mouse CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing the single-chain Fv (scFv)–CD28-ζ receptor have a greater capacity to secrete Tc1 cytokines, induce T-cell proliferation, and inhibit established tumor growth and metastases in vivo. The suppression of established tumor burden by cytotoxic T cells expressing the CD28/TCR-ζ chimera was critically dependent upon their interferon gamma (IFN-γ) secretion. Our study has illustrated the practical advantage of engineering a T-cell signaling complex that codelivers CD28 activation, dependent only upon the tumor's expression of the appropriate tumor associated antigen.

Introduction

The natural recognition and elimination of cancers by the adaptive arm of the immune system often fails and approaches to stimulate this adaptive antitumor immunity can be severely limited by tumor escape mechanisms.1-3 One promising approach conceived almost a decade ago was the genetic modification of T cells, resulting in engraftment with integral membrane single-chain Fv (scFv) chimeric signaling receptors, reactive with tumor-associated antigens.4,5 Such T cells have been shown to mediate tumor antigen-specific inhibition of tumor growth in vitro and in vivo, in a major histocompatability complex (MHC) class I–independent manner.6,7 Our recent study compared scFv-FcεRI-γ and T-cell receptor zeta (TCR-ζ) receptors reactive with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and showed the TCR-ζ molecule to be a superior signaling moiety in CD8+ T cells.7 Since T cells require 2 distinct signals for optimal activation,8the engagement of the TCR by peptide in the context of MHC, and a secondary signal provided by costimulatory or accessory molecules, then engineered T cells receiving only one signal after ligation of the tumor antigen might be predicted to be incompletely activated. Indeed, in one study, the ligation of an scFv-ζ chimeric receptor alone was shown to be insufficient to activate naive T cells, and rather a state of T-cell unresponsiveness (anergy) was induced.9

CD28 provides possibly the most potent comitogenic signal, functioning in synergy with the TCR, as a general amplifier of early TCR signal transduction and modulating the signaling environment around the site of TCR engagement.10,11 Costimulation of T cells via CD28 following ligation with tumor cell-surface CD80 and CD86 molecules or bispecific antibody (Ab)–mediated cross-linking to tumor-associated antigen (TAA) has been demonstrated to greatly stimulate subsequent tumor rejection and T-cell memory in vivo.12,13 Chimeric receptors incorporating CD28 have been shown to mediate enhanced T-cell activation in vitro.14-19Given that many tumor cells do not express costimulatory ligands,20 it was not clear whether this approach was sufficient to endow primary T lymphocytes with antitumor efficacy in vivo. Despite their promise, T lymphocytes engineered with scFv chimeras have had limited efficacy against established disease in mouse tumor models.7 Importantly, we now demonstrate that providing antigen-specific costimulation to gene-modified primary mouse T cells using CD28-containing scFv chimeric receptors can effectively eliminate established tumors using interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and perforin-dependent pathways.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human colorectal carcinoma cell lines COLO 205 and Lovo, mouse (C57BL/6 (B6)) colon adenocarcinoma MC-38 and its erbB2 transfectant MC-38-erbB2, the human breast carcinoma cell line MDA-MB-435 (a kind gift from Dr Robin Anderson, Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Melbourne, Australia), and the B6 sarcoma cell line 24JK (kindly provided by Dr Patrick Hwu, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) were maintained in RPMI 1640 or Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) at 37°C and 5% CO2 supplemented with the following additives: 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). All tumor cell lines did not express the CD80 and CD86 costimulatory ligands. The retroviral packaging cell lines, GP+E86 and PA317, and the fibroblast cell line NIH 3T3 were cultured in DMEM with additives. GP+E86 cells transduced with recombinant retroviral DNA were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL G418 (Life Technologies). Transduced T cells were cultured in DMEM containing 100 U/mL human recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL-2) (kindly provided by Chiron, Emeryville, CA).

Mice

Inbred BALB/c and BALB/c scid/scid (scid) mice were purchased from The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia. BALB/c perforin (pfp)–deficient (BALB/c pfp−/−) and BALB/c IFN-γ–deficient (BALB/c IFN-γ−/−) mice were bred at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute. Mice of 6 to 12 weeks of age were used in all experiments that were performed according to animal experimental ethics committee guidelines.

Chimeric receptor gene construction

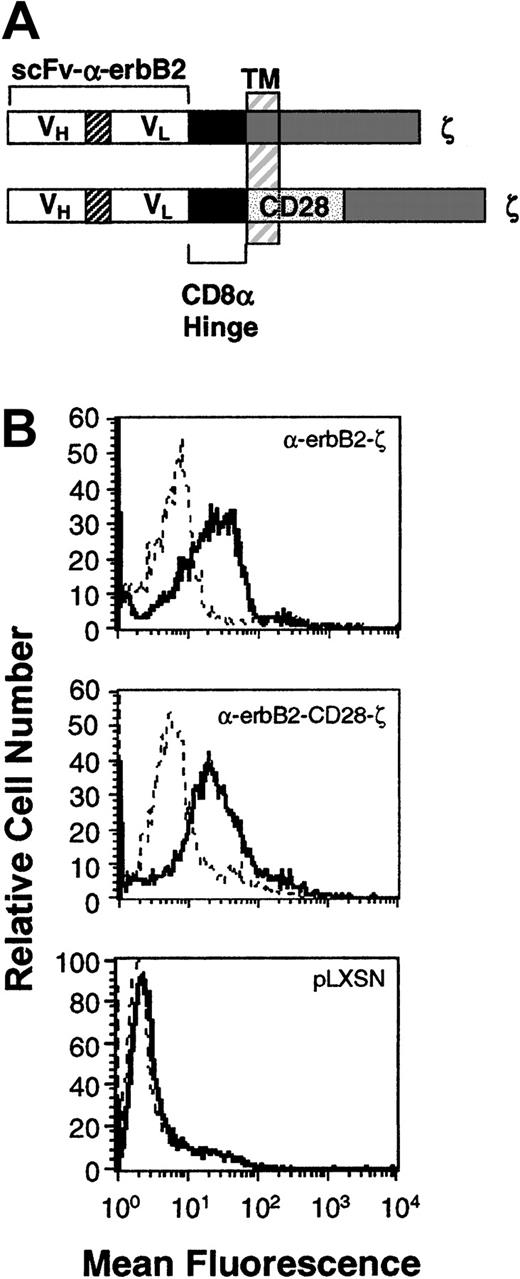

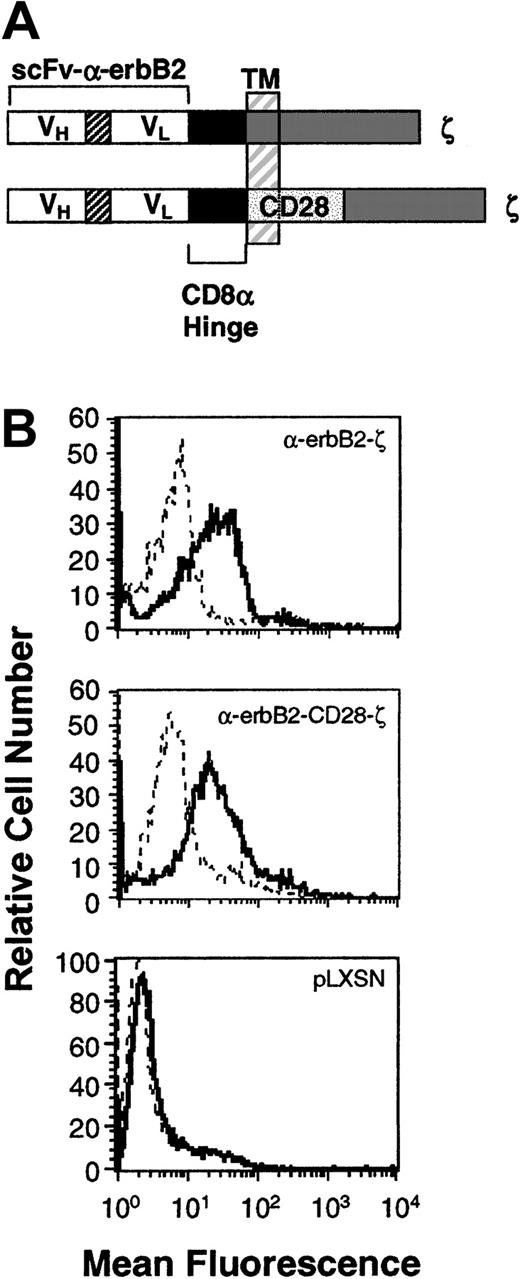

A 767-bp fragment of DNA coding for scFv of anti-erbB2 (a kind gift from Dr Winfried Wels, Institute of Experimental Cancer Research, Germany)21 and a marker epitope from c-myc was amplified by polymerase chain reaction from the pSW50-5 vector and subcloned into XbaI/BstEII-digested pRSVscFvγR (a kind gift from Zelig Eshhar, Weizmann Institute, Rehovot, Israel). The chimeric gene constructs were composed of the scFv-anti-erbB2 monoclonal antibody (mAb), a membrane proximal hinge region of human CD8, and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions of the human TCR-ζ chain (scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ) or the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions of the mouse CD28 signaling chain fused to the cytoplasmic region of TCR-ζ (scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ) (Figure1A). For detection purposes each receptor contained a c-myc tag epitope at the C-terminus of the VL region. The scFv-anti-erbB2 chimeric receptors were digested with SnaB1/XhoI and subcloned into theHpaI/XhoI restriction sites of the retroviral vector, pLXSN (a kind gift from Dusty Miller, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre, Seattle, WA) containing the long terminal repeat and a neomycin resistance gene under the control of an SV40 promoter.

Expression of the chimeric scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors in mouse T lymphocytes.

(A) Schematic representation of the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors. Each construct was composed of the VH and VL regions of the anti-erbB2 mAb joined by a flexible linker, a membrane-proximal hinge region, and the transmembrane (TM) and cytoplasmic regions of the human TCR-ζ chain or the mouse CD28 signaling chain fused to the intracellular domain of ζ. A c-myc tag epitope was incorporated into the C-terminus of the VL region for expression analysis. (B) Expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptors in primary mouse T lymphocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an anti–tag mAb or an IgG1 isotype control mAb. No expression was detected on T cells transduced with the retroviral vector, pLXSN, alone (bottom panel). Solid-line histogram depicts T cells stained with the anti–tag mAb; dashed-line histogram, T cells stained with IgG1 isotype control mAb.

Expression of the chimeric scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors in mouse T lymphocytes.

(A) Schematic representation of the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors. Each construct was composed of the VH and VL regions of the anti-erbB2 mAb joined by a flexible linker, a membrane-proximal hinge region, and the transmembrane (TM) and cytoplasmic regions of the human TCR-ζ chain or the mouse CD28 signaling chain fused to the intracellular domain of ζ. A c-myc tag epitope was incorporated into the C-terminus of the VL region for expression analysis. (B) Expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptors in primary mouse T lymphocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an anti–tag mAb or an IgG1 isotype control mAb. No expression was detected on T cells transduced with the retroviral vector, pLXSN, alone (bottom panel). Solid-line histogram depicts T cells stained with the anti–tag mAb; dashed-line histogram, T cells stained with IgG1 isotype control mAb.

Retroviral gene transfer of mouse spleen T lymphocytes

Stable GP+E86 ecotropic packaging cell lines expressing the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors were isolated as described previously.6,7 GP+E86 clones producing approximately 107 cfu/mL were used for transduction of mouse spleen T lymphocytes. Spleen cells from mice were initially depleted of red blood cells (RBCs) by hypotonic lysis with NH4Cl and enriched by passing through a nylon wool syringe as described previously.7 Enriched T lymphocytes (107) were then cocultivated for 72 hours with 5 × 105 viral-producing packaging cells in DMEM supplemented with 4 μg/mL polybrene, 5 μg/mL phytohemaglutinin (PHA) (Sigma, St Louis, MO), and 100 U/mL rIL-2. Following cocultivation, T cells were separated from adherent packaging cells, washed with DMEM, and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 100 U/mL rIL-2. T cells were subsequently analyzed for transduction efficiency by flow cytometry and used for in vitro and in vivo experiments. Consistent with previous observations,6 the majority of T cells selected by the transduction procedure were CD8+ (> 85% TCRβ+CD8+, ≤ 6% TCRβ+CD4+) (data not shown). In some experiments, transduced T cells were treated with anti–mouse CD4 Ab-conjugated immunomagnetic beads (GK1.5, Miltenvi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). CD4+ T cells were depleted using a MAC separator according to the supplier's specifications. Depletion (6% to 0% CD4+) was verified by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Detection of cell-surface chimeric receptor expression on mouse T lymphocytes was achieved by indirect immunofluorescence with ac-myc tag Ab purified from supernatants of mouse 9E10 cells,22 followed by staining with a phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled anti–mouse Ig mAb (Beckon Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Background fluorescence was assessed using a purified IgG1 isotope Ab (3S193; Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Melbourne, Australia). Cell-surface phenotyping of transduced cells was determined by direct staining with Quantum-Red–labeled anti-TCRαβ (clone H57-597; PharMingen, San Diego, CA); fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-CD4 (RM4-5; PharMingen); and Quantum-Red–labeled anti-CD8 (R-3762; Sigma) mAbs as previously described.6 Cell-surface phenotyping of tumor cell lines was determined by indirect immunofluorescence with anti–human erbB2 (9G6.10, Neomarkers, Fremont, CA), anti–mouse or anti–human CD80 (mouse, 1G10; human, BB1; Sigma), and CD86 (mouse, GL1; human, 2331[FUN-1]; Sigma) mAbs, followed by staining with a fluorophore-labeled anti–Ig mAb.

Antigen-specific binding, cytotoxicity, and cytokine secretion

The binding capacity of gene-modified mouse T lymphocytes was determined in a rosetting assay as described.7 The cytolytic capacity of transduced T cells was determined in a 6-hour51Cr-release assay. Mouse IFN-γ, IL-2, granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), IL-4, and IL-10 secretion by scFv-modified mouse T lymphocytes after erbB2 antigen ligation was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Transduced T cells (106) (transduced with LXSN plus scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ, scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ, or mock-transduced T cells) were cultured with 106erbB2+ (Lovo, COLO 205, MDA-MB-435 or MC-38-erbB2) or erbB2− (24JK or MC-38) tumor cells in 12-well plates for 20 hours. No exogenous IL-2 was added. Cytokine production through stimulation of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors was assessed for each T–effector cell population using soluble CD3 (1 μg/mL) (145.2C11; PharMingen) and CD28 (1 μg/mL) (37.51; PharMingen) mAbs. Following incubation, supernatants were harvested and the level of cytokine production was measured by ELISA (PharMingen) according to the supplier's specifications.

Proliferation assays

Proliferation assays were performed in 96-well U-bottom plates. The scFv-modified mouse T lymphocytes (105 cells/well, 5 × 104 cells/well, or 104 cells/well) were cultured in media alone, cocultured with irradiated MC-38-erbB2 or MC-38 tumor cells (105 cells/well), or stimulated with plate-bound CD3 plus CD28 mAb (1 μg/mL) for 3 days. Cultures were pulsed with 0.5 μCi/well (0.0185 MBq) of [3H]-thymidine (Amersham, Aylesbury, United Kingdom) for the last 16 hours of assay. No exogenous IL-2 was added. Incorporation of radioactivity was measured in a TRI-CARB 2100TR Liquid Scintillation Counter (Packard, Meriden, CT).

Adoptive transfer models

The antitumor response of transferred T cells was assessed against 2 different erbB2+ tumor cell lines following subcutaneous inoculation. First, 106 mouse 24JK sarcoma cells and/or 5 × 106 human COLO 205 colon carcinoma cells were injected subcutaneously into opposite flanks of groups of 5 to 10 scid mice. Spleen T lymphocytes from BALB/c mice (transduced with LXSN plus scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ, scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ, or mock-transduced T cells) were injected intravenously into groups of 10 scid mice at 6 hours (day 0, 5 × 106) and 24 hours (day 1, 5 × 106), on day 3 (107), or used for titration experiments at day 1 (105, 106, or 107) after tumor inoculation. In addition, adoptive transfer of scFv-transduced spleen T lymphocytes (5 × 106, day 0 and day 1) from BALB/c pfp−/−, BALB/c IFN-γ−/−, or BALB/c pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− mice were used to evaluate involvement of pfp and IFN-γ. In the second model, 5 × 106 MC-38 and/or MC-38-erbB2 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into opposite flanks of groups of 5 to 10 scid mice. Spleen T lymphocytes from BALB/c mice (transduced with LXSN plus scFv anti-erbB2-ζ, scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ, or mock-transduced T cells) were injected intravenously into groups of 10 scid mice at 6 hours (day 0, 5 × 106) and 24 hours (day 1, 5 × 106) or on day 3 (107) after tumor inoculation. Subsequent tumor growth was monitored daily and measured by a caliper square along the perpendicular axes of the tumors. The data were recorded as the mean tumor size (mm2, product of the 2 perpendicular diameters) ± SEM.

Experimental pulmonary metastasis model

Scid mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 106 human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells to establish pulmonary metastases. Spleen T lymphocytes (107) from BALB/c mice (transduced with LXSN plus scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ, -CD28-ζ, or mock-transduced T cells) were injected intravenously into groups of 10 mice at day 1, 5, or 10 after tumor inoculation. In addition, adoptive transfer of scFv-transduced spleen T lymphocytes (107, day 1) from BALB/c pfp−/−, BALB/c IFN-γ−/−, or BALB/c pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− mice were used to evaluate involvement of pfp and IFN-γ. Mice were monitored daily for tumor growth, indicated by respiratory distress and loss of body condition. There were 3 parameters of tumor growth, determined as follows: (1) in survival experiments, mice that were morbid were killed and the day of death recorded; (2) some groups of mice were killed at day 10 or 18 (when those not receiving T cells were morbid) and whole lung weight (g) was recorded; or (3) some groups of mice were killed at day 10 or 18 and harvested lungs were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histologic examination.

Results

Expression of the chimeric scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors in primary mouse T lymphocytes

Previous in vitro studies have demonstrated that CD28-containing chimeras can function in human T-cell lines23 and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs).14,16 The coexpression of both scFv-CD28 and scFv-ζ chimeras in Jurkat T cells (with specificities for different antigens) produced maximal levels of IL-2 in response to specific antigens compared with stimulation via either receptor alone.24 To avoid having to coexpress 2 receptors in T cells, we created a series of scFv (VH and VL) anti-erbB2 chimeric receptors containing the intracellular domains of CD28 with FcεRI-γ or TCR-ζ in series. Initially, chimeras were chosen following successful transient transfection in COS-7 cells and these were then stably expressed in Jurkat T cells. Jurkat T cells transduced with chimeras containing the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of CD28 fused to the TCR-ζ signaling moiety (Figure 1A) produced more IL-2 than Jurkat T cells equivalently expressing the scFv-ζ chimera (data not shown). These data were very encouraging; however, the effectiveness of this type of chimeric receptor needed to be tested in primary T lymphocytes, in vivo. Both receptor gene constructs were subcloned into the retroviral vector pLXSN and high titer virus–producing GP+E86 clones were used to transduce enriched naive T lymphocytes from BALB/c mouse spleens as previously described.6 High and equivalent levels of expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ and -CD28/ζ chimeric receptors were reproducibly detected on T cells (Figure 1B; n = 5).

Antigen-specific, MHC-independent lysis, enhanced cytokine production, and T-cell proliferation

We next sought to compare the activity of each cytoplasmic domain in stimulating T-cell function against erbB2+CD80−CD86− tumor target cells. The cytolytic capacities of T cells expressing either the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ receptors (T-scFv-ζ cells) or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors (T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells) were evaluated in standard 6-hour 51Cr release assays. T cells expressing either receptor were engrafted with the equivalent ability to specifically conjugate to (binding assays, data not shown) and lyse the erbB2+ human COLO 205 colon carcinoma, MDA-MB-435 mammary carcinoma, and mouse MC-38-erbB2 colon adenocarcinoma cell lines (Figure 2A). Equivalent levels of cytolysis were also mediated by both transduced T–effector cell populations after 16 hours (data not shown). Lysis of the erbB2 antigen-negative 24JK mouse sarcoma or MC-38 cell lines was not detected, demonstrating the antigen-specificity of cytolysis (Figure2A). Overall, the data indicated that the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera was functional, but that cytolytic function was neither enhanced nor diminished by fusing CD28 and ζ cytoplasmic domains.

Antigen-specific costimulation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells in vitro.

(A) Cytolytic function evaluated in a 6-hour 51Cr release assay. T cells transduced with the scFv-ζ (●) or scFv-CD28-ζ (○) chimeric receptors equivalently lysed the erbB2+tumors COLO 205, MDA-MB-435, or MC-38-erbB2, but not the erbB2− tumors 24JK or MC-38. T cells transduced with the pLXSN retrovirus alone (▪) were unable to lyse the erbB2−/+ tumors. The spontaneous lysis was less than 10% in all assays. Results are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. (B) Antigen-specific cytokine production. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (dotted bars) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or -CD28-ζ (▪) receptors and cultured with erbB2+ (Lovo, COLO 205, or MC-38-erbB2) or erbB2− (24JK or MC-38) tumor cells or stimulated with soluble CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 24 hours. Harvested supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ, GM-CSF (above) and TNFα, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 (data not shown) production by ELISA. T cells secreted minimal levels of IL-2 secretion and no TNF-α, IL-4, or IL-10. Results are expressed as pg/mL of cytokine secreted ± SE of duplicate samples and are representative of at least 5 experiments. (C) Proliferation was estimated by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (▧) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ (▪) receptors were cultured in media alone, with irradiated MC-38-erbB2 or MC-38 tumor cells or stimulated with plate-bound CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 3 days. Incorporation of radioactivity by the tumor cells was not detected. Results are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. Cytokine induction and proliferation via scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ and -ζ receptors were statistically compared by Mann-Whitney test (*P < .01, **P < .05).

Antigen-specific costimulation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells in vitro.

(A) Cytolytic function evaluated in a 6-hour 51Cr release assay. T cells transduced with the scFv-ζ (●) or scFv-CD28-ζ (○) chimeric receptors equivalently lysed the erbB2+tumors COLO 205, MDA-MB-435, or MC-38-erbB2, but not the erbB2− tumors 24JK or MC-38. T cells transduced with the pLXSN retrovirus alone (▪) were unable to lyse the erbB2−/+ tumors. The spontaneous lysis was less than 10% in all assays. Results are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. (B) Antigen-specific cytokine production. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (dotted bars) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or -CD28-ζ (▪) receptors and cultured with erbB2+ (Lovo, COLO 205, or MC-38-erbB2) or erbB2− (24JK or MC-38) tumor cells or stimulated with soluble CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 24 hours. Harvested supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ, GM-CSF (above) and TNFα, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 (data not shown) production by ELISA. T cells secreted minimal levels of IL-2 secretion and no TNF-α, IL-4, or IL-10. Results are expressed as pg/mL of cytokine secreted ± SE of duplicate samples and are representative of at least 5 experiments. (C) Proliferation was estimated by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (▧) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ (▪) receptors were cultured in media alone, with irradiated MC-38-erbB2 or MC-38 tumor cells or stimulated with plate-bound CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 3 days. Incorporation of radioactivity by the tumor cells was not detected. Results are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. Cytokine induction and proliferation via scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ and -ζ receptors were statistically compared by Mann-Whitney test (*P < .01, **P < .05).

One of the major consequences of CD28-mediated signaling is the increased production of T-cell cytokines.25 We therefore compared the capacity of T-scFv-ζ cells and T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells to produce Tc1 (IFN-γ, GM-CSF, IL-2, TNF-α) or Tc2 (IL-4 and IL-10) cytokines after specific ligation of erbB2+ cell lines (Figure 2B). T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells secreted more than 20-fold higher levels of IFN-γ and GM-CSF than T-scFv-ζ cells, in an erbB2 antigen-specific manner. The induction of these cytokines was at least equivalent to that observed in the same T cells incubated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAbs (Figure 2B). The level of IFN-γ produced by the T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells was not affected by the depletion of CD4+ T cells from the transduced effector population (T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells versus COLO 205-CD4+ + CD8+ T cells, 5991 pg/mL ± 53 pg/mL; CD4 depleted, 5283 pg/mL ± 186 pg/mL). Similar results were observed against other erbB2+ tumor cell lines. Induction of low levels of IL-2 secretion was also detected from T cells transduced with the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera or following anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAb stimulation (data not shown). Antigen or anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAb stimulation of the gene-modified CD8+ T cells did not result in the secretion of detectable TNF-α, IL-4, or IL-10 (data not shown). It is important to note, however, that antigen-specific ligation of the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera, when expressed in other T-cell subsets (eg, CD4+ T cells) or effector cells (eg, NK cells) could potentially stimulate the enhanced production of different Tc1 and Tc2 cytokines. Mock-transduced T cells secreted less than 50 pg/mL Tc1 or Tc2 cytokines after ligation of the erbB2+ cell lines. Another functional downstream effect of CD28 costimulation is enhanced proliferation.26We compared the proliferative capacity of T-scFv-ζ cells and T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells by [3H]-thymidine incorporation after specific ligation with irradiated erbB2+ tumor targets for 72 hours (Figure 2C). Ligation of the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera induced even greater CD8+ T cell (< 1% CD4+) proliferation compared with antibody-mediated stimulation of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors expressed on the same T cells (Figure 2C). T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells had more than 2-fold enhanced proliferative response compared with T-scFv-ζ cells at all T-cell concentrations examined (Figure 2C). After 6 days of culture, the proliferative potential of the transduced T cells significantly decreased; however, T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells still retained enhanced proliferative capacity compared with T-scFv-ζ cells (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrated that the scFv-CD28-ζ chimeric receptor was more effective at triggering cytokine production and T-cell proliferation compared with the scFv-ζ receptor, suggesting the CD28 component of the chimera was genuinely costimulatory in T cells.

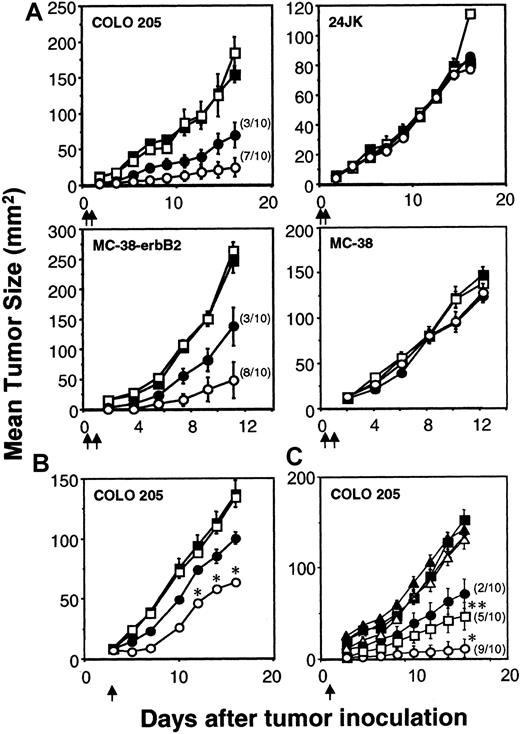

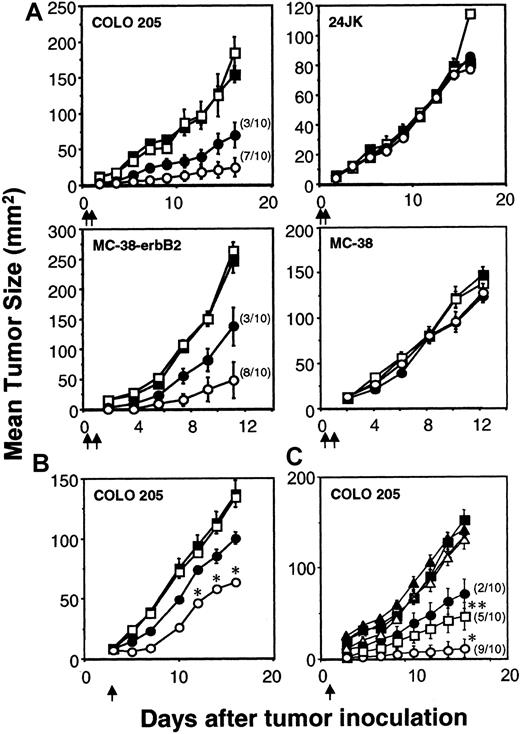

Inhibition of colon carcinoma by scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells

The capacity of the scFv-ζ and scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptors to stimulate optimal T-cell antitumor function was evaluated in adoptive transfer assays using tumor-bearing scid mice. Transduced T-scFv-ζ or T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells were adoptively transferred intravenously into scid mice 6 hours and 1 day after the subcutaneous inoculation of these mice with erbB2+ COLO 205 or MC-38 tumor in the right flank and erbB2- 24JK or MC-38 tumor, respectively, in the left flank. Both transduced T-cell populations were capable of mediating a significant antigen-specific antitumor response against the erbB2+ tumors, but not the erbB2− tumors (Figure 3A). Importantly, T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells demonstrated complete eradication of 7 of 10 COLO 205 tumors (Figure 3A) and 8 of 10 MC-38-erbB2 tumors (Figure 3A). Given the effectiveness of early treatment of the human and mouse colon adenocarcinomas with T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells, we next compared the antitumor efficacy of one dose of T cells (107cells) against 3-day established COLO 205 tumors (mean size ∼ 8 mm2). Although no complete tumor eradications were observed, statistically greater inhibition of growth of erbB2+ COLO 205 tumors was observed in mice injected with T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells compared with T-scFv-ζ cells (Figure 3B). Similar data were obtained with T-cell transfers into scid mice with established MC-38-erbB2 tumors (data not shown). To further compare the potency of T-scFv-CD28-ζ–mediated response(s) in vivo we assessed the antitumor efficacy of different doses of T-scFv-ζ cells or T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells (107, 106, or 105) injected into groups of 10 scid mice at day 1 after COLO 205 tumor inoculation (Figure 3C). Impressively, T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells were at least 10-fold more potent than T-scFv-ζ cells in inhibiting tumor growth (P < .01), and 106T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells eradicated tumors in 5 of 10 mice compared with 2 of 10 mice injected with 107 T-scFv-ζ cells (Figure 3C). The greater antitumor capacity of T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells was clearly evident from 3 independent experiments where collectively a total of 30 mice were inoculated with either 107 T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells or 107 T-scFv-ζ cells (T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells: 25 tumor-free versus T-scFv-ζ cells: 8 tumor-free,P < .0001).

Enhanced rejection of colon carcinomas in scid mice by scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells.

(A) Early treatment of erbB2+ tumors. Growth of the erbB2+ human COLO 205 colon carcinoma cells or mouse MC-38-erbB2 colon adenocarcinoma cells (right flank) and erbB2− 24JK mouse sarcoma cells or MC-38 cells (left flank), respectively, were injected subcutaneously in groups of 5 to 10 scid mice (as described in “Materials and methods”). Mice were injected intravenously with 2 doses (5 × 106) of BALB/c T cells transduced with the pLXSN vector alone (■), scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ chimera (●), or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimera (○) on day 0 and day 1 after tumor inoculation. The number of tumor eradications is shown in parentheses. Growth of the COLO 205 and 24JK tumors was also evaluated in scid mice receiving no T-cell transfer (▪). (B) Delayed treatment of 3-day established erbB2+tumors. The subcutaneous growth of erbB2+ COLO 205 tumors (right flank) or erbB2−24JK tumors (left flank, not shown) in groups of 5 to 10 scid mice. Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose (107) of BALB/c T cells transduced with the pLXSN alone (■), scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ chimera (●), or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimera (○) on day 3 after tumor inoculation. Growth of the COLO 205 tumor was also evaluated in scid mice receiving no T-cell treatment (▪). (C) Dose response of transduced T cells. The subcutaneous growth of erbB2+ COLO 205 tumors in groups of 10 scid mice. Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of 107 (●), 106 (▪), or 105 (▴) T-scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ cells or 107(○), 106 (■), or 105 (▵) T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells on day 1 after tumor inoculation. Growth of the COLO 205 tumor was evaluated in scid mice receiving no T-cell treatment (♦). For all experiments, results are represented as the mean tumor size (mm2) ± SEM. Arrows depict the days of T-cell transfer. COLO 205 tumor growth inhibited by T-scFv-CD28-ζ and T-scFv-ζ receptors was statistically compared at similar T-cell doses by Mann-Whitney test (*P < .05, **P < .0001).

Enhanced rejection of colon carcinomas in scid mice by scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells.

(A) Early treatment of erbB2+ tumors. Growth of the erbB2+ human COLO 205 colon carcinoma cells or mouse MC-38-erbB2 colon adenocarcinoma cells (right flank) and erbB2− 24JK mouse sarcoma cells or MC-38 cells (left flank), respectively, were injected subcutaneously in groups of 5 to 10 scid mice (as described in “Materials and methods”). Mice were injected intravenously with 2 doses (5 × 106) of BALB/c T cells transduced with the pLXSN vector alone (■), scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ chimera (●), or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimera (○) on day 0 and day 1 after tumor inoculation. The number of tumor eradications is shown in parentheses. Growth of the COLO 205 and 24JK tumors was also evaluated in scid mice receiving no T-cell transfer (▪). (B) Delayed treatment of 3-day established erbB2+tumors. The subcutaneous growth of erbB2+ COLO 205 tumors (right flank) or erbB2−24JK tumors (left flank, not shown) in groups of 5 to 10 scid mice. Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose (107) of BALB/c T cells transduced with the pLXSN alone (■), scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ chimera (●), or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimera (○) on day 3 after tumor inoculation. Growth of the COLO 205 tumor was also evaluated in scid mice receiving no T-cell treatment (▪). (C) Dose response of transduced T cells. The subcutaneous growth of erbB2+ COLO 205 tumors in groups of 10 scid mice. Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of 107 (●), 106 (▪), or 105 (▴) T-scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ cells or 107(○), 106 (■), or 105 (▵) T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells on day 1 after tumor inoculation. Growth of the COLO 205 tumor was evaluated in scid mice receiving no T-cell treatment (♦). For all experiments, results are represented as the mean tumor size (mm2) ± SEM. Arrows depict the days of T-cell transfer. COLO 205 tumor growth inhibited by T-scFv-CD28-ζ and T-scFv-ζ receptors was statistically compared at similar T-cell doses by Mann-Whitney test (*P < .05, **P < .0001).

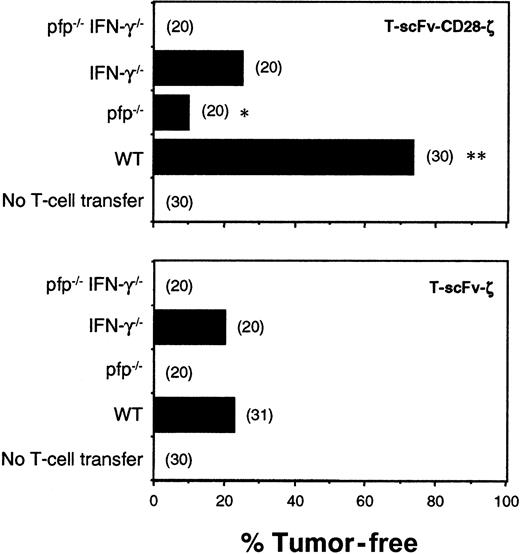

Perforin and IFN-γ are critical for the antitumor activity of T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells

To determine why T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells were so effective in vivo, we next sought to evaluate the relative importance of their cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretion in controlling tumor growth. T cells from BALB/c wild-type (WT), IFN-γ−/−, perforin (pfp)−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− mice were transduced with the scFv-CD28-ζ or scFv-ζ chimeric receptors. Importantly, expression of the scFv-CD28-ζ (Figure4A) and scFv-ζ (data not shown) chimeras in T cells from gene-targeted mice was equivalent to that detected in WT T cells. Phenotypic characterization of the scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from all mouse strains confirmed that only pfp−/− and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− T cells had defective cytolytic activity against the MC-38-erbB2+ tumor cells (Figure 4B). Transduced pfp−/− T cells retained a similar capacity to produce IFN-γ as WT T cells, following antibody-mediated stimulation of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors (data not shown). The proliferative ability of T cells from all 3 mutant mouse strains, following chimeric receptor ligation by erbB2 antigen or stimulation of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors, was observed to be at least equivalent to that of transduced WT T cells (Figure 4C). Having established the in vitro functional capacity of transduced T cells from each of the mutant strains of mice, the ability of these T cells to mediate in vivo tumor protection was compared against the antitumor activity of WT T cells.

Expression, cytotoxicity, and proliferation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/−mice.

(A) Equivalent expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptor in primary mouse T lymphocytes from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice as determined by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an anti–tag mAb (solid-line histogram) or an IgG1 isotype control mAb (dashed-line histogram). (B) The cytolytic activity of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT and gene-targeted mice was evaluated in a 6-hour51Cr release assay. Lysis of MC-38-erbB2+ tumor cells (closed symbols) by transduced IFN-γ−/− T cells (circles), but not pfp−/− (triangles) or pfp−/−INF-γ−/− T cells (diamonds), was equivalent to that mediated by gene-modified WT T cells (squares). All transduced effector T-cell populations were unable to lyse the erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells (open symbols). Results from a representative experiment are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples. Spontaneous lysis was consistently less than 10%. (C) The proliferative capacity of scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced mouse T lymphocytes from WT (striped bars), pfp−/− (dotted bars), IFN-γ−/− (open bars), and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− (closed bars) mice was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. The ability of receptor-modified T cells from gene-targeted mice to proliferate in response to erbB2 antigen or antibody-mediated crosslinking of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors was comparable to that observed for transduced WT T cells. All transduced T-cell populations failed to proliferate in response to erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells. Incorporation of radioactivity by tumor cells was not detected. Results from a representative experiment are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples.

Expression, cytotoxicity, and proliferation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/−mice.

(A) Equivalent expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptor in primary mouse T lymphocytes from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice as determined by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an anti–tag mAb (solid-line histogram) or an IgG1 isotype control mAb (dashed-line histogram). (B) The cytolytic activity of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT and gene-targeted mice was evaluated in a 6-hour51Cr release assay. Lysis of MC-38-erbB2+ tumor cells (closed symbols) by transduced IFN-γ−/− T cells (circles), but not pfp−/− (triangles) or pfp−/−INF-γ−/− T cells (diamonds), was equivalent to that mediated by gene-modified WT T cells (squares). All transduced effector T-cell populations were unable to lyse the erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells (open symbols). Results from a representative experiment are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples. Spontaneous lysis was consistently less than 10%. (C) The proliferative capacity of scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced mouse T lymphocytes from WT (striped bars), pfp−/− (dotted bars), IFN-γ−/− (open bars), and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− (closed bars) mice was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. The ability of receptor-modified T cells from gene-targeted mice to proliferate in response to erbB2 antigen or antibody-mediated crosslinking of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors was comparable to that observed for transduced WT T cells. All transduced T-cell populations failed to proliferate in response to erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells. Incorporation of radioactivity by tumor cells was not detected. Results from a representative experiment are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples.

Transduced T cells from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/−mice expressing the scFv-ζ or scFv-CD28-ζ chimeric receptors were injected intravenously into scid mice 6 hours and 1 day after COLO 205 tumor inoculation. Individual COLO 205 tumors grew rapidly in all untreated mice (Figure 5). WT T-scFv-ζ cells were somewhat effective and eradicated 7 of 31 tumors; however, by contrast, WT T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells were significantly more effective, eradicating 22 of 30 tumors. Regardless of the chimera transduced, T cells from pfp−/−IFN-γ−/−mice were completely ineffective, indicating that these 2 effector molecules accounted for all the antitumor activity of adoptively transferred T cells in this tumor model. Pfp was particularly important for effective tumor rejection since pfp−/−T-scFv-ζ cells did not eradicate any tumors, but pfp−/−T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells were partially effective. IFN-γ−/−T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells were less effective (5 of 20 tumors eradicated) than WT T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells (22 of 30 tumors eradicated), collectively suggesting that enhanced IFN-γ release was critical for the superior antitumor responses mediated by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells. Similar data were obtained with the transfer of C57BL6 (B6)–WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and IFN-γ−/−pfp−/−T cells into syngeneic B6 mice bearing MC-38-CEA subcutaneous tumors (data not shown), proving perforin and IFN-γ to be general effector mechanisms used by the T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells to reject tumors.

Pfp and IFN-γ were critical for the antitumor efficacy of T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells.

Subcutaneous growth of erbB2+ human COLO 205 cells in groups of 20 to 31 untreated and treated scid mice. Mice were injected intravenously with 2 doses (5 × 106) of T cells from BALB/c, WT, pfp−/−, IFN-γ−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− mice transduced with the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors on day 0 and day 1 after tumor inoculation. Mice were monitored for tumor growth for 100 days and results are recorded as the percentage of tumor-free mice in each group. The number of mice in each group is shown in parentheses. Tumor-free mice treated with T cells of the same strain were compared (T-scFv-CD28-ζ and T-scFv-ζ receptors) and statistically evaluated by Fisher exact test (*P ≤ .001, **P ≤ .0001).

Pfp and IFN-γ were critical for the antitumor efficacy of T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells.

Subcutaneous growth of erbB2+ human COLO 205 cells in groups of 20 to 31 untreated and treated scid mice. Mice were injected intravenously with 2 doses (5 × 106) of T cells from BALB/c, WT, pfp−/−, IFN-γ−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− mice transduced with the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptors on day 0 and day 1 after tumor inoculation. Mice were monitored for tumor growth for 100 days and results are recorded as the percentage of tumor-free mice in each group. The number of mice in each group is shown in parentheses. Tumor-free mice treated with T cells of the same strain were compared (T-scFv-CD28-ζ and T-scFv-ζ receptors) and statistically evaluated by Fisher exact test (*P ≤ .001, **P ≤ .0001).

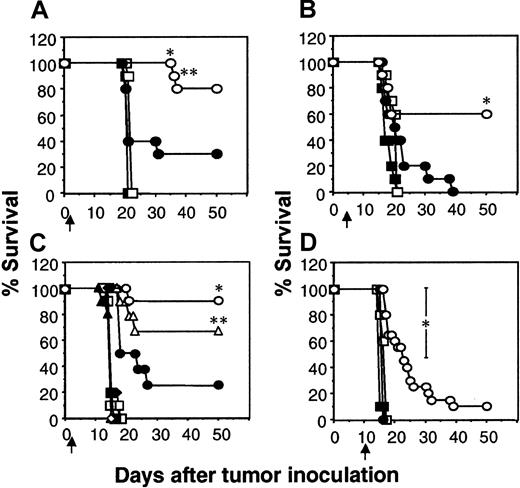

IFN-γ–dependent inhibition of established lung metastases by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells

Considering the ability of the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera to confer to T cells antitumor activity against established subcutaneous tumors, including MDA-MB-435 (data not shown), we next tested efficacy of transduced T cells against established human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma metastases in scid mice. Chimera-transduced T cells were adoptively transferred intravenously into scid mice on day 1, 5, or 10 after the intravenous inoculation of MDA-MB-435 tumor cells. The MDA-MB-435 tumor cells effectively lodge in the lung and grow rapidly, killing the mice within 16 to 20 days of inoculation. Adoptive transfer of T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells one day after tumor inoculation rescued 80% of mice (8 of 10), compared with 20% survival of mice receiving T-scFv-ζ cells (Figure 6A). The delay of T-cell transfer until day 5 reduced the number of tumor eradications (60% survival) mediated by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells (Figure 6B). T-scFv-ζ cells were partially effective, prolonging survival of 20% of mice beyond that observed for animals receiving mock-transduced T cells or no T-cell treatment; however, all the mice in this group did succumb to tumor (Figure 6B). Just as observed in the xenogeneic COLO 205 tumor model, the enhanced IFN-γ production by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells was absolutely critical for the superior antitumor activity of these effector cells against one-day established tumors, since the MDA-MB-435 tumors grew unaffected in mice that received IFN-γ−/−T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells (Figure 6C). Interestingly, in this model pfp played a reduced role in the T-scFv-CD28-ζ cell–mediated antitumor response(s) since the transfer of pfp−/−T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells still rescued 70% of mice.

IFN-γ– and perforin-dependent inhibition of established lung metastases by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cell transfer.

The survival of groups of 10 scid mice injected intravenously with erbB2+ human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells (5 × 106 cells). Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose (107) of BALB/c WT T cells transduced with the pLXSN vector alone (■), scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ chimera (●), or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimera (○) one day (A) or 5 days (B) after tumor inoculation. (C) Alternatively, mice were also injected intravenously with 107 T-scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ cells (closed symbols) or T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells (open symbols) from BALB/c WT (circles), pfp−/− (triangles), IFN-γ−/− (squares), and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− (diamonds) mice on day 1 after tumor inoculation. Control scid mice inoculated with MDA-MB-435 tumor cells received no T-cell treatment (crosses). (D) Treatment using WT T cells as in (A) and (B) 10 days after tumor inoculation. Control scid mice inoculated with MDA-MB-435 tumor cells received no treatment (▪). Results are representative of 2 experiments and are calculated as the percentage of each group surviving; arrows depict the days of T-cell transfer. Tumor-free mice treated with the same dose and strain of T cells were compared (T-scFv-CD28-ζ and T-scFv-ζ receptors) and statistically evaluated by Fisher exact test (*P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01).

IFN-γ– and perforin-dependent inhibition of established lung metastases by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cell transfer.

The survival of groups of 10 scid mice injected intravenously with erbB2+ human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells (5 × 106 cells). Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose (107) of BALB/c WT T cells transduced with the pLXSN vector alone (■), scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ chimera (●), or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimera (○) one day (A) or 5 days (B) after tumor inoculation. (C) Alternatively, mice were also injected intravenously with 107 T-scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ cells (closed symbols) or T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells (open symbols) from BALB/c WT (circles), pfp−/− (triangles), IFN-γ−/− (squares), and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− (diamonds) mice on day 1 after tumor inoculation. Control scid mice inoculated with MDA-MB-435 tumor cells received no T-cell treatment (crosses). (D) Treatment using WT T cells as in (A) and (B) 10 days after tumor inoculation. Control scid mice inoculated with MDA-MB-435 tumor cells received no treatment (▪). Results are representative of 2 experiments and are calculated as the percentage of each group surviving; arrows depict the days of T-cell transfer. Tumor-free mice treated with the same dose and strain of T cells were compared (T-scFv-CD28-ζ and T-scFv-ζ receptors) and statistically evaluated by Fisher exact test (*P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01).

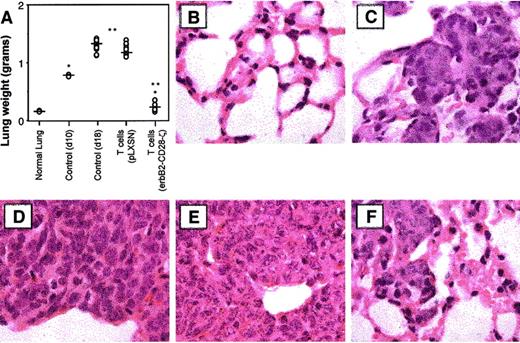

It must be noted that few immunotherapies have ever been described that can eliminate established solid tumors or metastases, even in mouse experimental models. Most dramatic was the potency of 107T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells against 10-day established lung metastases, with all the treated mice surviving longer than other treated mice and some surviving indefinitely (2 of 20 were tumor-free for more than 50 days, Figure 6D). By contrast, T-scFv-ζ cells had no significant antitumor effect against such advanced lung metastases. It should be noted that 10 days after MDA-MB-435 tumor inoculation, the lungs of untreated mice were considerably tumor burdened (whole lung weight, 0.78 ± 0.01 g) (Figure 7A). On day 18, 8 days after T-cell transfer, the mean weights of lungs isolated from mice receiving mock-transduced T cells (1.10 ± 0.15 g) or no treatment (1.38 ± 0.05 g) were approximately 6 times larger than those from T-scFv-CD28-ζ cell–treated mice (0.28 ± 0.08 g; *P < .01, **P < .001, n = 10) (Figure7A). Lungs isolated from normal scid mice weighed 0.17 ± 0.01 g. Histology (H&E staining) of these lungs at day 18 distinctly demonstrated a large reduction of MDA-MB-435 tumor mass (Figure 7F) upon T-scFv-CD28-ζ cell treatment with the maintenance of normal lung structure still evident in many areas of the lung. By comparison, lungs isolated from mice receiving no treatment, 10 days (Figure 7C) or 18 days after tumor inoculation (Figure 7D), were consumed with tumor cells and had completely lost all normal lung architecture. An equivalent level of tumor burden was also observed in lungs isolated at day 18 from mice receiving mock-transduced T cells (Figure 7E). These data graphically demonstrated for the first time the ability of adoptively transferred T cells to reduce established metastatic tumor burden.

Reduction of established lung tumor burden by T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells.

(A) Whole lung weight from groups of 10 scid mice, 18 days after intravenous injection of erbB2+ MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells (5 × 106). Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose (107) of either BALB/c WT T-pLXSN cells or T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells on day 10 after tumor inoculation. Normal whole lung weight (g) (no tumor, normal lung, n = 2) or control (not receiving T-cell transfer) whole lung weight from tumor-inoculated mice at day 10 (n = 2) or day 18 (n = 10) were also recorded. Significant differences in lung weight were determined by Mann-Whitney test and denoted (*P < .01, **P < .001). (B-F) Histology of lung sections (original magnification × 100) by hematoxylin and eosin staining as follows: (B) untreated mice (normal lung); (C) control MDA-MB-435 tumor growth at day 10 (no T-cell transfer); (D) control MDA-MB-435 tumor growth at day 18 (no T-cell transfer); (E) day 18 with T-pLXSN cell transfer; and (F) day 18 with T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cell transfer.

Reduction of established lung tumor burden by T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells.

(A) Whole lung weight from groups of 10 scid mice, 18 days after intravenous injection of erbB2+ MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells (5 × 106). Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose (107) of either BALB/c WT T-pLXSN cells or T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cells on day 10 after tumor inoculation. Normal whole lung weight (g) (no tumor, normal lung, n = 2) or control (not receiving T-cell transfer) whole lung weight from tumor-inoculated mice at day 10 (n = 2) or day 18 (n = 10) were also recorded. Significant differences in lung weight were determined by Mann-Whitney test and denoted (*P < .01, **P < .001). (B-F) Histology of lung sections (original magnification × 100) by hematoxylin and eosin staining as follows: (B) untreated mice (normal lung); (C) control MDA-MB-435 tumor growth at day 10 (no T-cell transfer); (D) control MDA-MB-435 tumor growth at day 18 (no T-cell transfer); (E) day 18 with T-pLXSN cell transfer; and (F) day 18 with T-scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ cell transfer.

Discussion

The transfer of specific chimeric antigen-recognition receptors into T cells offers great potential to target T cells to any tumor-associated antigen of interest. Specifically, redirecting T cells using scFv of antibody-chimeric receptors enables the efficient binding of effector T cells to tumors in a non–MHC-restricted fashion, thus bypassing the MHC/peptide complex loss that is a major escape mechanism for most tumors.27 Nevertheless, previous scFv-chimeric receptor designs that incorporated TCR-ζ or FcεRI-γ intracellular signaling domains did not account for the need to provide T cells with 2 signals for activation, thus limiting the effectiveness of redirected T cells against many tumors that down-regulate or lose costimulatory ligands such as CD80 and CD86. In this study we have made a significant and practical advance in providing tumor costimulation by demonstrating the greatly enhanced in vivo function of an scFv-anti-erbB2-chimera containing both the CD28 and TCR-ζ signaling moieties fused in a single receptor. We have illustrated that primary mouse T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells produce greatly elevated levels of IFN-γ and enhanced proliferation upon erbB2 ligation and in so doing evoke a vigorous antitumor response in vivo. Direct comparison with T cells expressing an otherwise identical receptor that lacked the CD28 cytoplasmic domain demonstrated the superior efficacy of the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera in established human tumor and experimental metastasis models in scid mice. We have also obtained similar data using T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells recognizing carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), demonstrating the general utility of this approach (data not shown). The degree of control of established tumors and metastases lacking CD80/86 expression, by T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells, exceeded that afforded by other approaches using tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL),28 lymphokine activated killer (LAK) cells,29 or gene-modified TIL30 in conjunction with high-dose IL-2 administration.

A most striking observation from our studies using T cells from gene-targeted mice was that the superior antitumor efficacy of the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera (compared with the scFv-ζ receptor) in vivo was critically dependent on the antigen-specific secretion of the Tc1 cytokine, IFN-γ. By contrast, pfp was found to be essential for effective tumor rejection mediated by T cells expressing either chimeric receptor. Although a role for pfp in the direct lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis of tumors has been well documented,6,31 the most important antitumor activity of IFN-γ remains unclear. There are a number of studies suggesting that IFN-γ can mediate its effect on tumors directly or indirectly.32-34 Importantly, in our study, the lack of murine T-cell secreted IFN-γ activity on human tumor cell IFN-γ receptors excludes a direct mechanism of action of IFN-γ. Possible indirect mechanisms of action include the recruitment and activation of endogenous immune effector cells,35 the regulation of leukocyte-endothelium interactions,35,36 or the antiangiogenic properties of IFN-γ.26,37,38 Although scid mice lack mature T and B cells, the potential indirect mechanisms to be explored (above) require far more extensive study. While we have demonstrated the key need for T-cell IFN-γ secretion, the elevated secretion of other Tc1 proinflammatory cytokines may also be contributing to the antitumor response mediated by the T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells.39,40 Further adoptive transfer and immunohistology studies with redirected T cells from WT and other gene-targeted mice should reveal which effector molecules and host cells contribute to the improved efficacy of T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells. An alternative explanation for the superior antitumor response mediated by these gene-engineered T cells in vivo is that costimulation through CD28 can regulate not only cytokine secretion but also T-cell proliferation and survival.41 We have demonstrated that antigen-specific ligation of the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera resulted in enhanced expansion of the gene-modified T cells in vitro. We have not yet evaluated the proliferation and survival of scFv-CD28-ζ–engineered and –transferred T cells in tumor-bearing mice; however, another study has indicated that mouse T cells retrovirally engineered with TCR genes can survive up to 80 days after transfer into immunocompromised mice.42 Importantly, in the context of our study, it should be noted that IFN-γ normally promotes the death of antigen-activated T cells43 rather than promoting survival.

Another important observation in our study was the equivalent cytokine secretion triggered by the scFv-CD28-ζ receptor compared with ligating endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors on primary T cells with reactive mAbs. Therefore, signaling through the CD28 and TCR-ζ motifs of the scFv-chimera, closely aligned in cis, functions at least equivalently for cytokine induction and T-cell proliferation as when the 2 motifs are positioned physiologically in trans. This in itself was an advance on a previous similar study performed in transformed Jurkat T cells.15 We have not, as yet, investigated the signaling mechanisms by which the scFv anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ receptor triggers enhanced cytokine secretion or proliferation. The capacities of endogenous CD28 to induce cytokine gene transcription44,45 and influence and sustain TCR signaling10 46 are well defined. T-cell activation via the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera may also serve to further increase the strength and time of interactions between T cells and tumor cells, thereby enhancing T-cell responsiveness. In the future, it will be interesting to evaluate whether the scFv-CD28-ζ chimera mimics the synergistic signaling activities of endogenous TCR and CD28 or provides alternative signaling pathways.

It is notable that even the most successful recent studies that have redirected T-cell specificity using scFv chimeras7,30 or TCR genes42,47 have protected against minimal tumor burden. By contrast, we have successfully retrovirally infected the majority of primary mouse T cells and demonstrated significant efficacy of these T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells in vivo when administered distant from established (up to 10 days) and rapidly growing tumors. No loss of antigenic specificity occurred with the scFv approach despite the increased potency (> 10-fold) of these engineered T cells. Overall this study has demonstrated the practicality of providing T cells with primary and costimulatory signals using a single scFv-chimeric receptor that recognizes a tumor antigen. The T-scFv-CD28-ζ cells eliminated tumors in the absence of exogenous IL-2 administration, and given that similarly transduced human T cells produce IL-216this approach may eliminate IL-2 toxicity associated with other adoptive immunotherapies using TILs and LAK cells.48

Despite encouraging clinical results for cellular immunotherapies using LAK cells and TILs,48 their general application to all cancers has been hampered by lack of specificity, poor homing capabilities, and difficulty in isolating a sufficient number of these cells. Redirected CTL therapy involving expression of chimeric receptors has several advantages over other immunotherapies due to (1) abundance of naive T cells available for gene transfer, (2) variety of TAA expressed on a broad spectrum of tumors, and (3) MHC-unrestricted reactivity of scFv-chimeric receptors. Although in many instances the MHC/peptide may be a more specific target than a TAA, many tumors readily down-regulate the expression of MHC/peptide complexes. While effective gene-delivery and autoimmunity remain hurdles with redirected CTL approaches, rapid advances in gene transfer technology and humanization of vectors coupled with the encouraging in vivo data presented herein compel further translation of the scFv approach to eventual clinical trials of safety and efficacy. Our ultimate goal of optimizing the signaling capacity of scFv-chimeric receptors has been to significantly enhance the specificity and potency of antitumor T cells. Our demonstration of the efficacy and effector mechanisms provided by a novel scFv-CD28-ζ receptor in vivo represent a significant advance in genetically providing T cells with the specificity and appropriate costimulation to reject tumors.

The authors wish to thank Dr Ian Davis for his critical reading of this manuscript and the staff of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute animal facilities for the caring and maintenance of mice used in this study.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 5, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1041.

Supported by a program grant from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation and the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria. M.J.S. is currently supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NH&MRC) Principal Research Fellowship.

M.J.S. and P.K.D. contributed equally to this work as senior authors.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Phillip Darcy, Cancer Immunology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Locked Bag 1, A'Beckett St, Victoria, Australia, 8006; e-mail: p.darcy@pmci.unimelb.edu.au.

![Fig. 2. Antigen-specific costimulation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells in vitro. / (A) Cytolytic function evaluated in a 6-hour 51Cr release assay. T cells transduced with the scFv-ζ (●) or scFv-CD28-ζ (○) chimeric receptors equivalently lysed the erbB2+tumors COLO 205, MDA-MB-435, or MC-38-erbB2, but not the erbB2− tumors 24JK or MC-38. T cells transduced with the pLXSN retrovirus alone (▪) were unable to lyse the erbB2−/+ tumors. The spontaneous lysis was less than 10% in all assays. Results are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. (B) Antigen-specific cytokine production. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (dotted bars) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or -CD28-ζ (▪) receptors and cultured with erbB2+ (Lovo, COLO 205, or MC-38-erbB2) or erbB2− (24JK or MC-38) tumor cells or stimulated with soluble CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 24 hours. Harvested supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ, GM-CSF (above) and TNFα, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 (data not shown) production by ELISA. T cells secreted minimal levels of IL-2 secretion and no TNF-α, IL-4, or IL-10. Results are expressed as pg/mL of cytokine secreted ± SE of duplicate samples and are representative of at least 5 experiments. (C) Proliferation was estimated by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (▧) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ (▪) receptors were cultured in media alone, with irradiated MC-38-erbB2 or MC-38 tumor cells or stimulated with plate-bound CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 3 days. Incorporation of radioactivity by the tumor cells was not detected. Results are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. Cytokine induction and proliferation via scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ and -ζ receptors were statistically compared by Mann-Whitney test (*P < .01, **P < .05).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/9/10.1182_blood-2002-04-1041/4/m_h82123313002.jpeg?Expires=1769252626&Signature=D93ZHmL--K83GntzwksPYrfC6Vl9degwlafytqji8LPEpwR2KVMAqT9P4qzU4d3ONog7WYxzEiRKCdSoze7e-z0hra6zTnjCTFH52oqhsGRXeATWDKFzFrGaJASCbNppy9QtafD52AeQ8Ir0ypH7Yoxf8wMPZB~xhC54thNvI2klxZonTha1DVrzpp7j75ZL5FQnlYsB1mPWd6jfoHOiyNDBqaiswjtOuJlhVdpD~8Bca9YsnA4oA2YEzGLwI-m1uDRhFCtpuvp6anB~RV-WGCTZxeZmTgjfUQN4x32vCF0Sivc928a4xbRjzhBnPB9Lg0pzle6UVJBBnKOqGYwTbg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Expression, cytotoxicity, and proliferation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/−mice. / (A) Equivalent expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptor in primary mouse T lymphocytes from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice as determined by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an anti–tag mAb (solid-line histogram) or an IgG1 isotype control mAb (dashed-line histogram). (B) The cytolytic activity of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT and gene-targeted mice was evaluated in a 6-hour51Cr release assay. Lysis of MC-38-erbB2+ tumor cells (closed symbols) by transduced IFN-γ−/− T cells (circles), but not pfp−/− (triangles) or pfp−/−INF-γ−/− T cells (diamonds), was equivalent to that mediated by gene-modified WT T cells (squares). All transduced effector T-cell populations were unable to lyse the erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells (open symbols). Results from a representative experiment are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples. Spontaneous lysis was consistently less than 10%. (C) The proliferative capacity of scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced mouse T lymphocytes from WT (striped bars), pfp−/− (dotted bars), IFN-γ−/− (open bars), and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− (closed bars) mice was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. The ability of receptor-modified T cells from gene-targeted mice to proliferate in response to erbB2 antigen or antibody-mediated crosslinking of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors was comparable to that observed for transduced WT T cells. All transduced T-cell populations failed to proliferate in response to erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells. Incorporation of radioactivity by tumor cells was not detected. Results from a representative experiment are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/9/10.1182_blood-2002-04-1041/4/m_h82123313004.jpeg?Expires=1769252626&Signature=tVslmqdyNwCsXCFuL9jT2nDRBrqjeiOL7gb-C7AyrIIWd9IDFTy4S-dLVYTsMBy8U5Rwp9f2WPvDZNaSkOp4s45hr7Ol1HWau9nae-7o4sxMWYsWPMR6AZ9Sw4tpJnMEDCsqJIHxsKudW1gC7ag8-fKU0EZF3SrRh1yuj9ARAvChCuHeciabeWNbvnm5CtgZfiyOeHcFDXdKj9XdIEP7WSKoIm6DmaG9RQOB9XiTuT5Jmaxaq5EkmsxVEg0Jk0cLYmKEhDqZ2kBqJj5wnyL5VSCHVqt5GfwpRI9jpCdiBkB2HryYNQORHZ9pJktxxI2b1X7VNLw5xiNgADI1u-urnQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. Antigen-specific costimulation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells in vitro. / (A) Cytolytic function evaluated in a 6-hour 51Cr release assay. T cells transduced with the scFv-ζ (●) or scFv-CD28-ζ (○) chimeric receptors equivalently lysed the erbB2+tumors COLO 205, MDA-MB-435, or MC-38-erbB2, but not the erbB2− tumors 24JK or MC-38. T cells transduced with the pLXSN retrovirus alone (▪) were unable to lyse the erbB2−/+ tumors. The spontaneous lysis was less than 10% in all assays. Results are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. (B) Antigen-specific cytokine production. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (dotted bars) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or -CD28-ζ (▪) receptors and cultured with erbB2+ (Lovo, COLO 205, or MC-38-erbB2) or erbB2− (24JK or MC-38) tumor cells or stimulated with soluble CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 24 hours. Harvested supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ, GM-CSF (above) and TNFα, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 (data not shown) production by ELISA. T cells secreted minimal levels of IL-2 secretion and no TNF-α, IL-4, or IL-10. Results are expressed as pg/mL of cytokine secreted ± SE of duplicate samples and are representative of at least 5 experiments. (C) Proliferation was estimated by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. Mouse T cells transduced with pLXSN alone (▧) or pLXSN encoding the scFv-anti-erbB2-ζ (■) or scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ (▪) receptors were cultured in media alone, with irradiated MC-38-erbB2 or MC-38 tumor cells or stimulated with plate-bound CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 3 days. Incorporation of radioactivity by the tumor cells was not detected. Results are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples and are representative of at least 2 experiments. Cytokine induction and proliferation via scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ and -ζ receptors were statistically compared by Mann-Whitney test (*P < .01, **P < .05).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/9/10.1182_blood-2002-04-1041/4/m_h82123313002.jpeg?Expires=1769365914&Signature=h8NVEy58SZ5sQ4p~oQN~-AduS9V5l-ynbsA~on34ZqBf3K29GAl1iyJR~af~o3N0kLzfOGhcz-BA1ooUi9Kq7PKw7lgTtAuqN9DtyWxLT~4i7IXEpKOf0sgBmvyrnUks2dF7z2x1aVWXfYcmC9d1oD4rAbvxABSETzO1EhZwWVRYblkatlGFoQR8witQFvnZ~j9SmuQ9yfihBNN3EUr5cv6v-EPFJMX0frrUv1fFu81IRc6Z78i01KXw-nS0hSh~Zs2nCpzt93V3EbA43436t5n-~x89Tc3czhgaGHzSUoq1LW8V2aeelCAmF1taXIvla0mLA9QpQzHKhRVNTwmKZw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Expression, cytotoxicity, and proliferation of scFv-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/−mice. / (A) Equivalent expression of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ chimeric receptor in primary mouse T lymphocytes from WT, IFN-γ−/−, pfp−/−, and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice as determined by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an anti–tag mAb (solid-line histogram) or an IgG1 isotype control mAb (dashed-line histogram). (B) The cytolytic activity of the scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced T cells from WT and gene-targeted mice was evaluated in a 6-hour51Cr release assay. Lysis of MC-38-erbB2+ tumor cells (closed symbols) by transduced IFN-γ−/− T cells (circles), but not pfp−/− (triangles) or pfp−/−INF-γ−/− T cells (diamonds), was equivalent to that mediated by gene-modified WT T cells (squares). All transduced effector T-cell populations were unable to lyse the erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells (open symbols). Results from a representative experiment are expressed as percent specific51Cr release ± SE of triplicate samples. Spontaneous lysis was consistently less than 10%. (C) The proliferative capacity of scFv-anti-erbB2-CD28-ζ–transduced mouse T lymphocytes from WT (striped bars), pfp−/− (dotted bars), IFN-γ−/− (open bars), and pfp−/−IFN-γ−/− (closed bars) mice was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation at 72 hours. The ability of receptor-modified T cells from gene-targeted mice to proliferate in response to erbB2 antigen or antibody-mediated crosslinking of endogenous CD3 and CD28 receptors was comparable to that observed for transduced WT T cells. All transduced T-cell populations failed to proliferate in response to erbB2−MC-38 parental tumor cells. Incorporation of radioactivity by tumor cells was not detected. Results from a representative experiment are expressed as means ± SE of triplicate samples.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/9/10.1182_blood-2002-04-1041/4/m_h82123313004.jpeg?Expires=1769365914&Signature=B7-bgnjTi~Uw7L2MCEF42tkasRZ-b1x89f-NtxF6zJCD6vTSA9ypWkRcZ39LNT9F8zYZnCfCJxMKA5EWwYAeTcZwiWFyHLd9RlnVQpRa8lk1OCmpfgAO6KTALYMDpjX7cR-n0Ht6uFEGU93w9jRq6M7Pa8-9EM3FPuvV7iUnRR~i4H0Y17lENls6w8v~C79F-Xz7hcQhwDayh43lAqWsHhpQCVWf9u6H-~cfEZxrntFxNnt8fHUSz8NZYq~P1M6Zc7M~fyFSlhCAUMNm07ZRemsaCTTrtMIiSqVKBYQbxwpurpCYXyAWwJUNjqisKKSZZtNutbH-2rPBnVNzUNtY9g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)