Abstract

Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), also called type 2 dendritic cell precursors or natural interferon (IFN)–producing cells, represent a cell type with distinctive phenotypic and functional features. They are present in the thymus and probably share a common precursor with T and natural killer (NK) cells. In an effort to identify genes that control pDC development we searched for genes of which the expression is restricted to human pDC using a cDNA subtraction technique with activated monocyte-derived DCs (Mo-DCs) as competitor. We identified the transcription factor Spi-B to be expressed in pDCs but not in Mo-DCs. Spi-B expression in pDCs was maintained on in vitro maturation of pDCs. Spi-B was expressed in early CD34+CD38− hematopoietic progenitors and in CD34+CD1a− thymic precursors. Spi-B expression is down-regulated when uncommitted CD34+CD1a− thymic precursors differentiate into committed CD34+CD1a+ pre-T cells. Overexpression of Spi-B in hematopoietic progenitor cells resulted in inhibition of development of T cells both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, development of progenitor cells into B and NK cells in vitro was also inhibited by Spi-B overexpression. Our results indicate that Spi-B is involved in the control of pDC development by limiting the capacity of progenitor cells to develop into other lymphoid lineages.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are specialized antigen-presenting cells that both initiate primary specific immune responses and delete potentially autoreactive T cells.1There are different subsets of DCs with distinct cell surface phenotypes, function, and anatomic localization.2,3 A recently identified member of the DC lineage is the plasmacytoid DC (pDC),4 also referred to as a type 2 DC precursor5 (pre-DC2) or natural interferon (IFN)–producing cell.6 These cells have been found in the peripheral blood of adults and neonates7,8 and in the T-cell areas of tonsils.4 Interestingly pDCs have the capacity to produce high levels of type I IFNs that block viral replication.6,9 Moreover, pDCs express a distinct pattern of Toll-like receptors suggesting that they might have developed through different evolutionary pathways to recognize different microbial antigens.10 On activation with CD40L or with virus, the pDCs differentiate into mature DCs, which can effectively stimulate T cells. Depending on the way the pDCs are activated, the mature DC2s induce T cells, producing distinct sets of cytokines: interleukin 4 (IL-4) and IL-5 after activation of the pDCs with IL-3 and CD40L11 or IL-10 and IFN-γ after activation of the pDCs with virus.12,13 Importantly pDCs are prominently present in the medulla of the thymus14 15 and may therefore play a critical role in shaping the T-cell–receptor repertoire within this organ.

Recent evidence strongly suggests that pDCs are of lymphoid origin. pDCs lack myeloid-related markers CD13 and CD334,14and express pre-T-cell receptor (pTα)14,16 and λ-like transcripts,15 which are essential for T- and B-cell development, respectively. More importantly, we observed recently that inhibitors of DNA-binding (Id) proteins, Id2 and Id3, which efficiently block the transcriptional activities of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins, inhibit development of pDCs but not of myeloid DCs.17 These observations along with the demonstration that these factors also block B-cell18 and T-cell development19 support a lymphoid origin of pDCs.

A number of transcription factors involved in lymphoid-lineage specification in progenitor cells have been identified. GATA-3 and Pax5 are essential for T- and B-cell development, respectively.20,21 Notch1 is required for T-cell development and inhibits B-cell development and therefore determines T/B-cell diversification22 and the HLH factor Id2 is compulsory for development of natural killer (NK) cells.23bHLH factors are involved in pDC development17 but are also required for T- and B-cell development (for a review, see Eben Massari and Murre24), raising the question which transcription factor(s) might control the diversification of pDCs on one hand and T, B, and NK cells on the other hand. To this end we searched for genes that are specifically transcribed in pDCs. One of the genes identified encodes the transcription factor Spi-B. We show here that forced expression of Spi-B in hematopoietic precursors impairs development of T, B, and NK cells and stimulates development of pDCs.

Materials and methods

Reagents and mAbs

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to CD3, CD4, CD8, CD38, CD45RA, and CD123 conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE) or with peridinin chlorophyll protein (Per-cp) were obtained from Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems (BDIS; San Jose, CA). CD1-PE was obtained from Coulter/Immunotech (Luminy, France). CD4-tricolor (TC), CD8-TC, CD34-TC, and CD45RA-TC were from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark). BDCA-2–fluorescin isothiocyanate (FITC) and –PE were obtained from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Anti–nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR)–allophycocyanin (APC) was obtained from Chromaprobe (Mountain View, CA). IL-7, stem cell factor (SCF), and thrombopoietin (TPO) were obtained from R & D Systems (Abingdon, United Kingdom).

Generation of DCs from monocytes in vitro

Monocyte-derived DCs (Mo-DC) were generated from monocytes as described25 by culturing them 5 days in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 200 ng/mL) and IL-4 (5 ng/mL) (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ). After those 5 days cells were activated 24 and 48 hours in the presence of CD40L-transfected L cells (1 L cell for 5 DCs).

Purification of plasmacytoid cells and generation of DC2s from the CD4+CD1c− pDCs

pDCs were isolated from human tonsils as detailed previously4 and activated by IL-3 (10 ng/mL) in the presence of CD40L-transfected L cells (1 L cell for 5 DCs) for 24, 48, and 96 hours.

Purification of blood cells and generation of CD34-derived DCs

CD34-derived DCs were obtained after 6 and 12 days of culture of CD34+ progenitor cells in the presence of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and GM-CSF.26 DCs were activated by CD40L-transfected cells. B lymphocytes were obtained from CD4-depleted human tonsils. B cells were activated by CD40 activation using L cells expressing CD40L. Blood mononuclear cells were obtained from human peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation. T lymphocytes were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by negative depletion27 and activated by CD28-CD3. Granulocytes were isolated by Lympholyte-poly centrifugation (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, ON, Canada) and activated by phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) and ionomycin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 3 hours.

Subtractive hybridization

The subtractive hybridization procedure was performed using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–select cDNA subtraction kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), as per the manufacturer's protocols. Poly-A+ RNAs, selected as described by Mueller et al27 from pDCs and DC2s, were used as tester, and activated DC1 Poly-A+ RNAs as driver. To clone subtracted pDC cDNA, 10 PCRs (nested) were pooled and resolved on 2% low-melting agarose gel; 12 gel slices in the 0.3- to 1.3-kb size range were cut out and cloned with pCRII TOPO TA Cloning (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The inserts were sequenced by automatic sequencing. Comparisons against GenBank and dbest databases as well as protein homology prediction were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) blast server (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The cloned product perfectly matched with the human Spi-B cDNA sequence (accession no. X66079).

RT-PCR assays

Reversed transcriptase (RT)–PCR assays were performed on RNA samples from purified T cells, granulocytes, PBMCs, tonsillar B cells, and day 12–harvested CD34+-derived DCs, before and after specific activation and CD34+ precursor cells isolated from fetal liver or thymus. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was performed on reverse-transcribed RNA from the different populations. GAPDH primers were 5′-ACCATGCTCGCCCTGGA (upstream) and 5′-GGCTAGCGAAGTTCTCC (downstream). In some experiments hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) was used as a housekeeping gene. The sequences of the HPRT primers were 5′-TATGGACAGGACTGAACGTCTTGC (upstream) and 5′-GACACAAACATGATTCAAATCCCTGA (downstream). The sequences of the Spi-B primers were 5′-GGAGTGCTGCCCTGCCATAA (upstream) and 5′-CCCCCACCCCAGATGAGATT (downstream).

Western blot analysis

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed on total cell lysates, and nuclear extracts obtained from 12 × 106 cells were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE followed by electrotransfer onto nitrocellulose. Western blotting was performed as described.28 The membrane (polyvinylidene fluoride [PVDF]) was probed with an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody (kindly provided by Dr Françoise Moreau-Gachelin, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Institut Curie, Paris, France). Preimmune serum and anti–Spi-B were added at a 1:200 dilution in triethanolamine-buffered saline (TBS) containing 1% casein for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by using secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany).

Retroviral transductions

Full-length human Spi-B and the natural splice variant lacking the DNA-binding domain (ΔSpi-B, kindly provided by Dr Françoise Moreau-Gachelin)29 cDNA was ligated into the multiple cloning site of retroviral vector LZRS upstream of an internal ribosomal entry site and enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) as described previously.18,19 Control viruses were LZRS-IRES-GFP. For some experiments we used as control virus LZRS-IRES with, downstream placed, a deleted, signaling-incompetent mutant of the nerve growth factor receptor (ΔNGFR), kindly provided by Dr C. Bordignon.30 Helper virus–free recombinant retroviruses (titer 106/mL, as determined by transduction of mouse 3T3 fibroblast cells) were produced after transfection of the retroviral constructs into the 293T-based Phoenix (ΦNX-A) amphotropic packaging cell line and selection on the selectable marker puromycin.31 Transduction of CD34+CD38− fetal liver or CD34+CD1a− postnatal thymocyte cells was performed as described previously.32 33 Briefly, the progenitor cells were cultured overnight in the presence of 20 ng/mL IL-7 (R & D Systems) and 10 ng/mL SCF (R & D Systems) followed by incubation for 7 to 8 hours or overnight with virus supernatant in plates coated with fibronectin (30 μg/mL; Takara Biomedicals, Otsu, Shiga, Japan).

Isolation of CD34+ cells from fetal liver and postnatal thymus

The use of fetal liver and postnatal thymus tissue was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Netherlands Cancer Institute and was contingent on informed consent. Human fetal tissues were obtained from elective abortions. Gestational age was determined by ultrasonic measurement of the diameter of the skull and ranged from 14 to 20 weeks. Human fetal liver cells were isolated by gentle disruption of the tissue by mechanical means, followed by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep; Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway). Thymus was obtained from surgical specimens removed from children undergoing open heart surgery. Single-cell suspensions were made from postnatal thymus by mincing tissues and pressing them through a stainless steel mesh. Large aggregates were removed and the cells were washed once before separating subpopulations. The CD34+ cells were isolated from these samples by immunomagnetic cell sorting, using a CD34 separation kit (varioMACS, Miltenyi Biotec). The CD34+ fetal liver cells were stained with anti-CD34 and anti-CD38 mAbs and further purified into CD34+CD38− cells by sorting with a FACStar plus (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The purity of the CD34+CD38− cells used in this study was more than 99%. The CD34+ thymocytes were stained with anti-CD34 and anti-CD1a and separated into CD34+CD1a− and CD34+CD1a+ populations by cell sorting.

Differentiation assays

Development of CD34+ cells into pDCs was determined following coculture with the mouse stromal cell line S17 as described previously.17 The hybrid murine/human fetal thymic organ culture has been described previously.34 To monitor NK-cell development in a fetal thymic organ culture (FTOC), 10 ng/mL IL-15 was added at the onset of the culture. The medium containing IL-15 was changed every week.

To follow differentiation of T cells and pDCs in vivo we used an immunodeficient mouse strain transplanted with human fetal thymus fragments. RAG-2−/− γ common receptor (γc)−/− mice,35 which completely lack T, B, and NK cells, received a transplant of a human thymus by grafting small (1-2 mm) human fetal thymus and liver fragments subcutaneously in 300 μL Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) diluted 1:4 in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland). Eight to 12 weeks after grafting, a mixture of CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells transduced with Spi-B-IRES-GFP or with control-IRES-ΔNGFR were injected directly in the human thymus transplants of these mice. Two to 3 weeks later the mice were killed and the thymus was removed for further analysis.

The development of pDCs and B cells was assayed in a coculture of CD34+ progenitors with the murine marrow cell line MS-5 (kindly provided by Dr J. Plum, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium) in Iscove medium (Life Technologies) with 8% fetal calf serum.

Statistical analysis

To determine whether Spi-B significantly stimulates the development of pDCs from CD34+ progenitor cells, a paired 2-tailed Student t test was performed using Microsoft Excel 98.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis induced by Spi-B was measured in fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) CD34+CD1− and CD34+CD1+ postnatal thymocytes. Transduced cells were cultured at 200 000 cells/96-well plate in 200 μL Yssel medium supplemented with SCF and IL-7 (20 ng/mL each). At day 7 percentages of apoptotic and dead cells were determined by staining with annexin V–PE (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, CA) and 7-amino-actino mycin D (7-AAD; Becton Dickinson).

Results

Identification of Spi-B in pDCs

We performed a PCR-based subtraction technique on pDCs with monocyte-derived DC (DC1) as competitor. The subtractive hybridization technique was applied as described elsewhere.27 A mixture of freshly isolated pDC and pDC activated by IL-3 and CD40L for 24 hours (5 × 106 cells) was used as a tester, and 108 CD40-activated MoDC were used as competitor (driver). cDNA tester was cut with RsaI; the adapters were ligated and amplified after hybridization in the presence of driver. This technique combines normalization and subtraction in a single procedure. Thus, the resulting PCR products are restriction fragments of pDC cDNA, which are absent, or at least rare, in DC1 cells. pDC cDNA fragments were cloned and sequenced, and 30% of these clones contained unknown sequences.

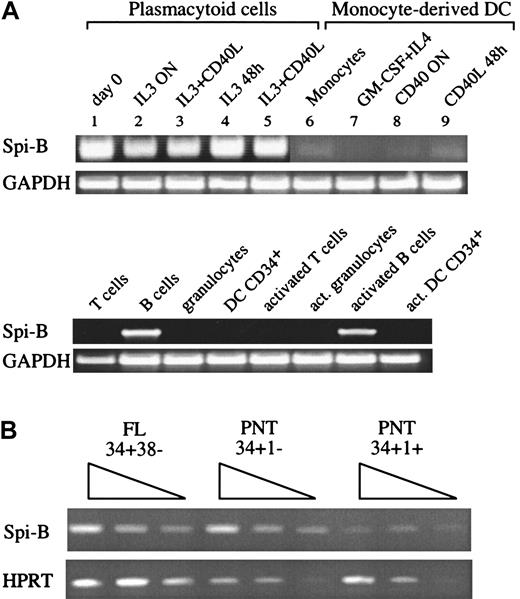

Of interest, we found 8 clones encoding the transcription factor Spi-B. This factor belongs to the Ets family with a relatively high degree of homology with PU.1 and was detected in lymphoid cells but in contrast to PU.1, not in monocytes, granulocytes, or myeloid cell lines.36 Spi-B transcripts have been shown to be present in B and in developing T cells but not in most mature T cells.36-38 To verify the restricted expression of Spi-B, RT-PCR analysis was first performed on pDC and Mo-DC cDNAs (Figure1A). pDCs (line 1) but not Mo-DCs (lines 7-9) expressed Spi-B mRNA. Importantly, Spi-B mRNA is maintained in pDCs even after activation (lines 2-5). In addition, monocytes (line 6), peripheral blood T cells, and granulocytes did not express Spi-B. As expected, high levels of Spi-B mRNA were found in resting and activated B cells. Spi-B is also expressed in CD34+CD38− fetal liver (FL) cells, a population highly enriched for pluripotent stem cells (Figure 1B). To obtain insight into the expression of Spi-B in human T-cell development, we analyzed various subsets of precursor T cells isolated from postnatal human thymus (PNT). The earliest precursor in the human thymus expresses the stem cell antigen CD34 and lacks CD1a.39 CD34+CD1a− cells have the capacity to develop into various lineages including T, NK, and pDC. These cells develop to CD4+CD8+ immature T cells through CD34+CD1a+ and CD3−CD4+CD8− intermediates. RT-PCR analysis of these subsets revealed that Spi-B is expressed in CD34+CD1a− cells and is down-regulated in CD34+CD1a+ cells (Figure 1B).

Expression of Spi-B in hematopoietic cells.

(A) A 35-cycle RT-PCR for Spi-B expression was performed on DC2 (lines 1-5), freshly isolated (line 1), after IL-3 activation (for 12 hours, line 2; for 48 hours, line 4), and after IL-3 and CD40L activation, (for 12 hours, line 3; 48 hours, line 5). Monocytes (line 6), Mo-DCs (line 7), and CD40-activated DC1 (overnight, line 8; 48 hours, line 9).

Expression of Spi-B in hematopoietic cells.

(A) A 35-cycle RT-PCR for Spi-B expression was performed on DC2 (lines 1-5), freshly isolated (line 1), after IL-3 activation (for 12 hours, line 2; for 48 hours, line 4), and after IL-3 and CD40L activation, (for 12 hours, line 3; 48 hours, line 5). Monocytes (line 6), Mo-DCs (line 7), and CD40-activated DC1 (overnight, line 8; 48 hours, line 9).

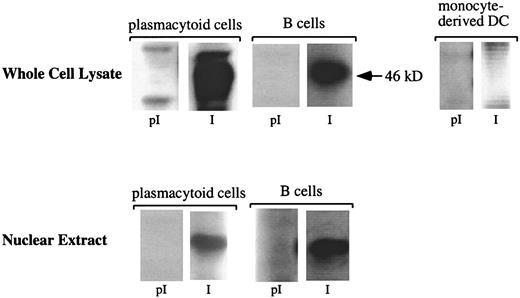

To determine whether pDCs express Spi-B protein, Western blot analyses were performed on whole cell lysates and nuclear extracts from pDCs, Mo-DCs, and mature B cells as positive control (Figure2). Comparable levels of the 46-kDa Spi-B protein were detected, using a polyclonal antiserum raised against the 160 N-terminal amino acids of Spi-B,28 in whole cell lysates from pDCs, mature tonsillar B cells, and nuclear extracts from pDCs and mature tonsillar B cells. No Spi-B protein was precipitated with the preimmune serum. As expected, the Jurkat T-cell line did not express Spi-B protein (data not shown).

pDCs express Spi-B at the protein level.

Western blot analysis of Spi-B protein from pDCs. Cytoplasmic or nuclear protein extracts were prepared from pDCs as indicated in “Materials and methods.” The extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using preimmune sera (pI) and anti–Spi-B sera (I). Blots were visualized by chemoluminescence. The size of molecular mass standard is indicated on the right. Tonsillar B cells were used as positive controls.

pDCs express Spi-B at the protein level.

Western blot analysis of Spi-B protein from pDCs. Cytoplasmic or nuclear protein extracts were prepared from pDCs as indicated in “Materials and methods.” The extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using preimmune sera (pI) and anti–Spi-B sera (I). Blots were visualized by chemoluminescence. The size of molecular mass standard is indicated on the right. Tonsillar B cells were used as positive controls.

Effects of Spi-B on development of pDCs

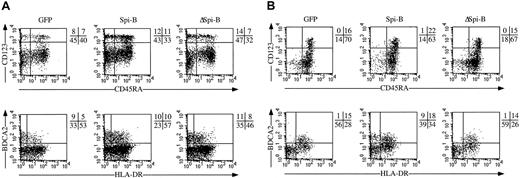

To investigate the function of Spi-B, we transduced hematopoietic CD34+CD38− fetal liver stem cells with a retroviral vector harboring Spi-B upstream of IRES-GFP DNA19 and tested the transduced cells in various differentiation assays for pDC, T-, B-, and NK-cell development. Stem cells transduced with Spi-B-GFP, with ΔSpi-B or control GFP were incubated with the murine stromal cell line S17.17Following 5 days of incubation the phenotypes of the Spi-B-GFP+, ΔSpi-B-GFP, and control GFP+ cells were analyzed (Figure3A). In this period of incubation, the total numbers of cells do not increase and therefore differences in the percentages of various cell populations reflect those in the absolute numbers of cells. Whereas the ΔSpi-B-GFP–transduced and the control-transduced cells developed into pDCs in a manner comparable to untransduced cells, we consistently observed that more pDCs are present in the Spi-B-GFP+ population that developed from CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells. A similar weak stimulation of pDC development was seen on coculture of Spi-B–transduced CD34+CD1a− thymocytes with S17 cells (Figure 3B).

Effect of Spi-B on development of pDCs.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver (A) or CD34+CD1a− postnatal thymus (B) were transduced with LZRS Spi-B-IRES-GFP, LZRS ΔSpi-B-IRES-GFP, or with control-IRES-GFP and incubated with S17 cells for 5 to 7 days for postnatal thymocytes and fetal liver cells, respectively. The quadrants were placed to include 99% of the cells stained with control antibodies. The cell recoveries of all samples were the same; thus, the differences in percentages of pDCs indicated in the figure reflect the differences in absolute numbers of pDCs generated in this system.

Effect of Spi-B on development of pDCs.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver (A) or CD34+CD1a− postnatal thymus (B) were transduced with LZRS Spi-B-IRES-GFP, LZRS ΔSpi-B-IRES-GFP, or with control-IRES-GFP and incubated with S17 cells for 5 to 7 days for postnatal thymocytes and fetal liver cells, respectively. The quadrants were placed to include 99% of the cells stained with control antibodies. The cell recoveries of all samples were the same; thus, the differences in percentages of pDCs indicated in the figure reflect the differences in absolute numbers of pDCs generated in this system.

Statistical analysis revealed that this difference in percentages (and thus numbers) of pDCs between Spi-B–transduced samples as compared with control- and ΔSpi-B–transduced samples is significant (Table1). These results confirm that Spi-B modestly stimulates pDC development.

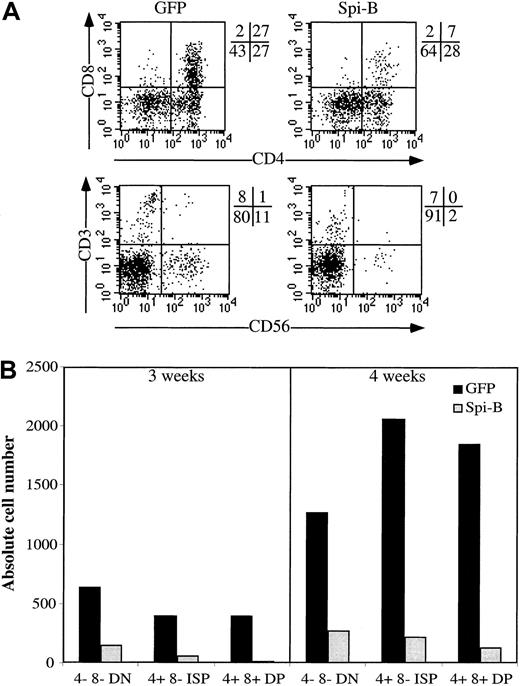

Inhibition of T- and NK-cell development by Spi-B

Because Spi-B stimulated pDC development in the S17 assay, we investigated the effects of overexpression of Spi-B on development of other lymphoid lineages. CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced with Spi-B or GFP control vector and incubated in an FTOC. After incubation for 3 to 4 weeks, we analyzed the phenotypes of the GFP+ cells in both cultures. T-cell differentiation was inhibited at an early stage because in the Spi-B/GFP gate only a few CD4+CD8+double-positive (DP) cells could be detected when analyzed after 3 weeks (Figure 4A). Moreover, the number of the Spi-B-GFP+ cells generated per 1000 transduced CD34+CD38− cells was strongly reduced compared with that of controls (Figure 4B). Analysis of the FTOC incubated for 4 weeks revealed the presence of close to normal proportions of cells expressing CD3, CD4, or CD8 but the numbers of cells generated per 1000 input cells remained strongly reduced compared with the control (Figure 4B). Development of NK cells was also strongly inhibited (Figure 4).

Effect of Spi-B overexpression on T-cell development in an FTOC.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced with LZRS Spi-B-IRES-GFP or with control-IRES-GFP and incubated with murine fetal lobes as indicated in “Materials and methods.” The lobes were seeded with 20 000 progenitor cells per lobe. (A) Expression of CD4, CD8, CD3, and CD56 of the Spi-B– and control-transduced cells. The quadrants were placed to include 99% of the cells stained with control antibodies. (B) Number of output cells per 1000 input progenitor cells. The transduction efficiencies were determined 3 days after the transduction. Based on the percentages of GFP+ cells in the samples, the numbers of input progenitor cells were calculated. The output numbers of each population were calculated on the basis of the total numbers of cells harvested from the FTOC, the percentages of transduced cells, and the percentages of each population.

Effect of Spi-B overexpression on T-cell development in an FTOC.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced with LZRS Spi-B-IRES-GFP or with control-IRES-GFP and incubated with murine fetal lobes as indicated in “Materials and methods.” The lobes were seeded with 20 000 progenitor cells per lobe. (A) Expression of CD4, CD8, CD3, and CD56 of the Spi-B– and control-transduced cells. The quadrants were placed to include 99% of the cells stained with control antibodies. (B) Number of output cells per 1000 input progenitor cells. The transduction efficiencies were determined 3 days after the transduction. Based on the percentages of GFP+ cells in the samples, the numbers of input progenitor cells were calculated. The output numbers of each population were calculated on the basis of the total numbers of cells harvested from the FTOC, the percentages of transduced cells, and the percentages of each population.

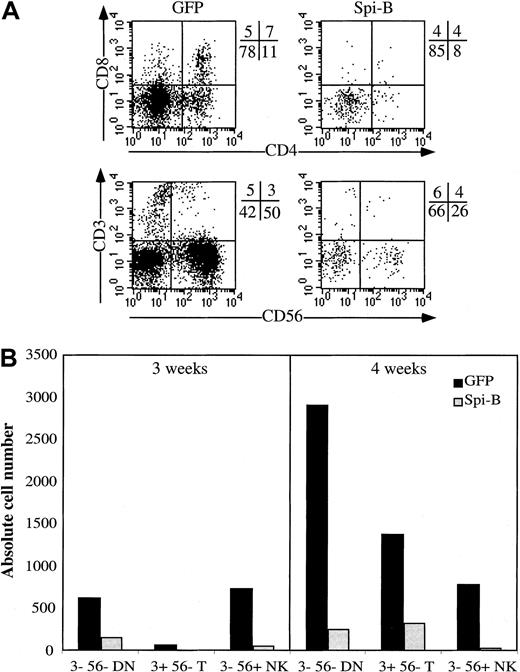

To better reveal the effect of Spi-B on development of NK cells, we added IL-15 to the FTOC, which stimulates NK-cell development in an FTOC.40 Figure 5A confirms that Spi-B–transduced CD34+ cells have a strongly diminished capacity not only to develop into T but also to NK cells. The absolute numbers of NK cells were also strongly reduced by Spi-B (Figure 5B). Although not shown, ectopic expression of Spi-B also inhibited NK-cell development of CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells and of CD34+ thymocytes in a mixture of IL-15, SCF, and IL-7.

Effect of Spi-B on development of NK cells in an FTOC with IL-15.

The conditions of the FTOC were the same as indicated in Figure 4except that IL-15, 10 ng/mL, was added to the FTOC. (A) The cell-surface antigen expression of the cells harvested from the FTOC. (B) The absolute numbers of output cells of each subpopulation per 1000 input progenitor cells calculated as indicated in Figure 4B.

Effect of Spi-B on development of NK cells in an FTOC with IL-15.

The conditions of the FTOC were the same as indicated in Figure 4except that IL-15, 10 ng/mL, was added to the FTOC. (A) The cell-surface antigen expression of the cells harvested from the FTOC. (B) The absolute numbers of output cells of each subpopulation per 1000 input progenitor cells calculated as indicated in Figure 4B.

Spi-B influences T-cell and pDC development in vivo

Our data suggest that Spi-B expression in precursor cells within the thymus affects the lineage decision of CD34+ precursors into T cells or pDCs. To confirm this point, we examined whether Spi-B affects T/pDC diversification in a system where differentiation of both cell types could be followed simultaneously. In the in vitro FTOC system we do not observe appearance of pDCs. Therefore, we used a human immunodeficient mouse model in which we can monitor development of both pDCs and T cells.41 In this model gene-marked progenitor cells are injected into a human thymus grafted subcutaneously in RAG2−/−γc−/− double-deficient mice. Such mice lack T, B, and NK cells35 and are therefore excellent recipients of human fetal thymus and liver (as sources of stem cells) grafts. Like the thymus in the classical human severe combined immunodeficient mouse, in which the thymus is grafted under the kidney capsule,42 the subcutaneously placed human thymus in the RAG2−/−γc−/− mouse has a normal architecture and contains normal proportions of all thymocyte subsets.41 The thymus is palpable and therefore easily accessible for intrathymic injection without the need for surgery.41 We transduced CD34+CD38− fetal liver stem cells with Spi-B-GFP and with a control virus harboring a second marker, a signaling-incompetent mutant of the NGFR with a deletion in the cytoplasmic domain (ΔNGFR30) and injected a mixture of these transduced cells into the grafted human thymus. The use of 2 different markers, one for the Spi-B–modified and one for the control, was necessary because a faithful comparison of development of modified with control transduced cells can only be made when injected in the same thymus. The thymic transplants of 2 transplanted mice can be sufficiently different to make a comparison between these 2 samples unreliable when injected into 2 different thymi. The transduction efficiencies of the CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells with Spi-B-GFP and control-ΔNGFR in 3 different experiments were comparable (7% ± 2%). Because from both samples the same number of cells were injected, the input number of Spi-B and control transduced cells were the same. Two weeks later we harvested the thymus of each animal and compared the phenotypes of the Spi-B–transduced (GFP+) and the control-transduced cells (ΔNGFR+; Figure 6). The percentages of 2 transduced cell populations harvested from the thymi were strikingly different because 0.7% of the thymocytes expressed GFP and 5.7% ΔNGFR, indicating a strong effect of Spi-B on the expansion of the cells in this setting. The percentage of total CD4+CD123+ cells that should include all pDCs in the ΔNGFR+ samples was 2%, but it needs to be noted that almost no CD123high cells were present in these samples. The percentage of CD123+CD4+ in the Spi-B–transduced samples was significantly higher (8%) than in the ΔNGFR+ samples. The CD123+CD4+cells in the Spi-B samples also expressed CD45RA. Part of these cells also expressed BDCA2. This was not unexpected because in a normal thymus the percentage of BDCA2+ is around 50% to 70% of the percentage of all CD123+ cells (including CD123low cells). Our pair of fluorogen-labeled antibodies against BDCA2 and NGFR did not permit a simultaneous staining of BDCA2+ cells in the ΔNGFR-control samples, but because the percentage of CD123+CD4+ cells in the control is much lower than in the Spi-B–transduced sample we think it is fair to conclude that ectopic Spi-B expression in CD34+CD38− cells results in a higher proportion of pDCs in vivo, which is consistent with the in vitro data. Importantly, as was also observed in the in vitro FTOC assay, the proportion of CD4+CD8+ T-cell lineage cells in the Spi-B+ samples is lower than in the control ΔNGFR-transduced cells. This T cell–inhibiting effect of Spi-B is more dramatic if one considers the much lower expansion of the Spi-B–transduced cell samples.

Effect of Spi-B on T and pDC development in vivo.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced with control-IRES-ΔNGFR and Spi-B-IRES-GFP. After transduction the cells were mixed 1:1 and in total 1 × 106 cells were injected into the thymus transplanted subcutaneously 8 weeks prior to injection of the transduced cells. Two weeks later the mice were killed, the thymus was removed, and single-cell suspensions were made by gently cutting the thymus and pressing the fragments through a stainless sieve. The cells were stained with antibodies against the NGFR, CD123, CD4, CD8, CD45RA, BDCA2, and HLA-DR. We excluded the cells expressing extremely high levels of CD4 and CD123 (CD4+CD123+ cells [8%]) because they may represent an artifact.

Effect of Spi-B on T and pDC development in vivo.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced with control-IRES-ΔNGFR and Spi-B-IRES-GFP. After transduction the cells were mixed 1:1 and in total 1 × 106 cells were injected into the thymus transplanted subcutaneously 8 weeks prior to injection of the transduced cells. Two weeks later the mice were killed, the thymus was removed, and single-cell suspensions were made by gently cutting the thymus and pressing the fragments through a stainless sieve. The cells were stained with antibodies against the NGFR, CD123, CD4, CD8, CD45RA, BDCA2, and HLA-DR. We excluded the cells expressing extremely high levels of CD4 and CD123 (CD4+CD123+ cells [8%]) because they may represent an artifact.

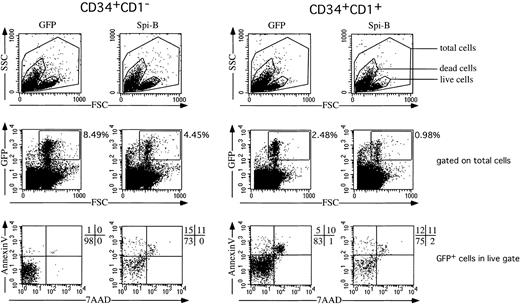

Ectopic expression of Spi-B in early T-cell precursors increases apoptosis

The observation that pDC development is modestly stimulated, whereas that of T cells is inhibited, together with the finding that DP T cells appear at later time points in the FTOC, may be explained by assuming that Spi-B inhibits proliferation or survival (or both) of T-cell precursors. To examine this possibility, we transduced CD34+CD1a− and CD34+CD1a+ cells with Spi-B or GFP and cultured those cells for 7 days with IL-7 and SCF. The transduction efficiencies as measured after 2 days were comparable. At 7 days, however, the percentages of the Spi-B–transduced cells were only half of the control (Figure 7). This suggested already a reduced survival of the pre-T cells. Inspection of the annexin V versus 7-AAD expression revealed that the Spi-B–transduced cells contain many more annexinV+7-AAD−apoptotic cells than in the control. This effect was most striking in the CD34+CD1a− population although the same pattern could also be observed in the CD34+CD1a+ cells (Figure 7). These findings strongly suggest that Spi-B inhibits T-cell development by induction of apoptosis in T-cell precursors rather than inhibiting the differentiation itself. The effect of Spi-B is specific because it does not induce apoptosis in pDCs. Furthermore, ectopic Spi-B expression in 293T human embryonic kidney cells did not induce apoptosis in the cells (supplemental figure on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figure link at the top of the online article).

Effect of Spi-B on cell survival.

Spi-B– or control-transduced CD34+CD1− and CD34+CD1+ postnatal thymocytes were cultured in the presence of SCF and IL-7. In this cytokine combination most cells generated from both CD34+ populations express CD4 and CD8α, indicating that the cytokines induce committed T-cell precursors in this culture period.52 After 7 days, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS analysis on annexin V and 7-AAD.

Effect of Spi-B on cell survival.

Spi-B– or control-transduced CD34+CD1− and CD34+CD1+ postnatal thymocytes were cultured in the presence of SCF and IL-7. In this cytokine combination most cells generated from both CD34+ populations express CD4 and CD8α, indicating that the cytokines induce committed T-cell precursors in this culture period.52 After 7 days, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS analysis on annexin V and 7-AAD.

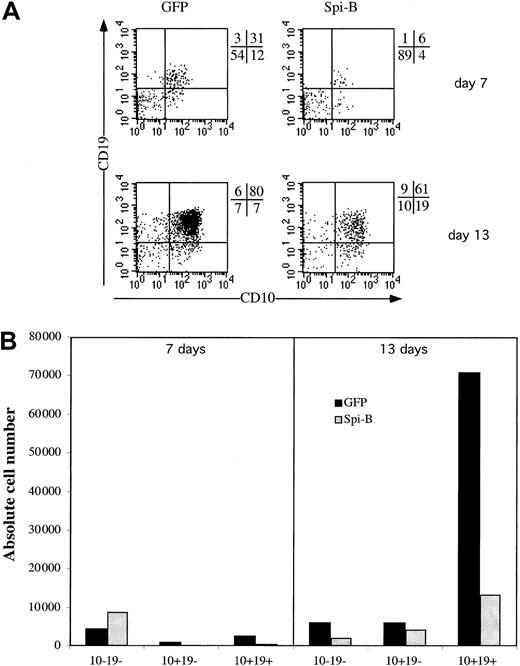

Spi-B inhibits B-cell development

Having established that Spi-B expression affects pDC versus T/NK-cell development, we examined whether Spi-B expression affects B-cell development. We transduced CD34+ fetal liver cells with Spi-B/GFP and control-GFP and cultured these cell samples with the stromal cell line MS-5. The cells were cocultured on the murine marrow line MS-5 for 2 weeks and analyzed for their expression of the B-cell markers CD10 and CD19 at days 7 and 14. Ectopic expression of Spi-B gives a strong block in the development of B cells. At 7 days the percentage of CD10+CD19+ is only 6% for the Spi-B–transduced population compared with 31% in the control cells (Figure 8). Moreover, when analyzed at 14 days the absolute number of CD10+CD19+ cells developing from CD34+ progenitor cells was strongly reduced by the forced expression of Spi-B (Figure 8). In the same assay at 5 days the percentage of pDCs was elevated similar to the results shown in Figure 3A (data not shown).

Effect of Spi-B on B-cell development.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced and put into coculture at 50 000 cells with 30 000 MS-5 cells. (A) B-cell development was determined by the expression of the markers CD10 and CD19 at 7 and 13 days of culture. (B) The absolute numbers of output cells of each subpopulation per 1000 input progenitor cells calculated as indicated in the legend to Figure 4B.

Effect of Spi-B on B-cell development.

CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced and put into coculture at 50 000 cells with 30 000 MS-5 cells. (A) B-cell development was determined by the expression of the markers CD10 and CD19 at 7 and 13 days of culture. (B) The absolute numbers of output cells of each subpopulation per 1000 input progenitor cells calculated as indicated in the legend to Figure 4B.

Discussion

Evidence has been obtained that pDCs are lymphocyte related. Early CD34+CD1a− thymic precursors have the capacity to develop into T cells, NK cells, and pDCs in vitro,17suggesting that they are derived from a common precursor. Moreover, thymic pDCs possess a number of characteristics, including expression of CD2, CD5, and CD7 and pTα consistent with a common origin with T and NK cells. This raised the question how lineage specification of uncommitted CD34+CD1a− thymocyte precursors is regulated. Previously we found that Id proteins, which inhibit transcriptional activities of E proteins, block T-cell and pDC development but stimulate NK-cell development,17,19,43indicating that the ratio of Id versus E proteins regulates specification into the NK lineage on one hand and pDC and T-cell lineages on the other. These experiments left unresolved the question on the identity of the factor(s) that regulate the T/pDC split. Using a subtractive hybridization approach aimed to identify proteins, including transcription factors, specific for pDC, we found Spi-B as one of the genes expressed in pDCs and their mature descendants and not in monocytes and in Mo-DCs. Analysis of the expression of Spi-B furthermore confirmed earlier reports that this factor is present in mature and activated B cells and in early T-cell precursors but not in myeloid cells.36-38 We demonstrate here that overexpression of Spi-B in CD34+ precursor cells strongly interferes with their capacity to develop in vitro into T and NK cells, whereas, in contrast, this factor moderately promoted development of pDCs. The results of these in vitro experiments strongly suggest that Spi-B is involved in regulation of lymphoid-lineage specification. This point was strengthened in experiments using the human RAG2−/−γc−/− mouse model in which we could follow development of T cells and pDCs in the same system. When control-transduced and Spi-B–transduced CD34+cells were coinjected in a human thymus graft we observed a clear reduction of T-lineage cells and an increase of pDC development by Spi-B. Interestingly, Spi-B expression in uncommitted CD34+CD1a− thymocytes is considerably higher than in the committed CD34+CD1a+ population, indicating that Spi-B is down-regulated when precursor cells commit to the T-cell lineage. This finding together with the inhibition of T-cell development by Spi-B overexpression makes it plausible that down-regulation of Spi-B is required to ensure correct execution of the T-cell developmental program.

Inhibition of T-cell development by Spi-B is not absolute because CD4+CD8+ cells are formed in vitro FTOCs and in vivo in the thymus transplanted into Rag2−/−γc−/− mice. These observations suggest that Spi-B enhances the chance that a given common precursor will develop along the pDC lineage, but once a precursor cell has made the choice for the T-cell lineage Spi-B overexpression does not affect further development into mature T cells. As a consequence, in an FTOC, close to normal CD4/CD8 ratios can be observed in Spi-B/GFP+ cells at time points beyond 4 weeks, although the total numbers of developed cells remain much lower than in the controls. Similarly, in vitro NK-cell development is strongly reduced by Spi-B in terms of output numbers of mature NK cells but is not completely blocked. Our findings are consistent with the idea that Spi-B is directing precursor cells to develop along the pDC lineage by reducing the numbers of committed T- and NK-cell precursors. It is likely that this reduction is achieved by induction of apoptosis of T- and NK-cell precursors because the results presented in Figure 7demonstrate that ectopic expression of Spi-B results in induction of apoptosis of CD34+ thymic precursor cells cultured in IL-7. Overexpression of Spi-B also impairs B-cell differentiation (Figure 8). Thus, Spi-B may be implicated in securing pDC commitment. Transcription factors implicated in commitment of a particular lineage inhibit development of other lineages. A prominent example is Pax-5, which is required for progression of B-cell development and inhibits development to other hematopoietic lineages.21 Another example is Id2 that is needed for NK-cell development23and inhibits T-cell, B-cell, and pDC development.17Although Spi-B modestly stimulates development of pDCs in vitro, this does not necessarily imply that this protein is required for pDC development. To answer this question Spi-B−/− mice have to be analyzed for the presence of the murine equivalent of pDCs.44 45

It would also be of interest to investigate the presence of pDCs in PU.1-deficient mice. The Ets domains of PU.1 and Spi-B display 70% homology and the factors bind to similar DNA sites, although the transactivation domains are very different. The expression profiles of these 2 transcription factors are widely different because Spi-B expression appears to be limited to lymphoid cells, whereas PU.1 is expressed in myeloid cells as well.36-38 PU.1 is essential for B-cell development and important for T-cell differentiation.46-48 Importantly, PU.1-deficient mice lack myeloid CD8α+ DCs, but the numbers of CD8α+ DCs present in the thymus are normal.49 If pDCs are present in PU.1−/− mice this may be further evidence for a lymphoid origin and may help to answer the question whether there is a relationship between CD8α+ lymphoid DCs and pDCs.

The mechanism of interference of Spi-B with T-cell development is unknown. T cell–specific target genes controlled by Spi-B have yet to be found. However, the mechanism of inhibition of erythroid development by PU.1 may provide a clue. Analysis of PU.1−/− embryos and of PU.1−/− ES chimeras revealed that this factor is required for development of myeloid but not for erythroid lineages.46,47 Overexpression of PU.1 in precursor cell lines or in avian hematopoietic precursor cells increases proliferation of proerythroblasts but inhibits further differentiation due to interference with DNA binding of GATA-1,50,51 a transcription factor essential for terminal differentiation of erythrocytes. The effect of Spi-B on pDC/T-cell diversification is similar to that of PU.1 on myeloid and erythroid differentiation. Given the homologies between PU.1 and Spi-B and between GATA-1 and GATA-3, it is tempting to speculate that Spi-B interferes with T-cell development by negatively regulating GATA-3. If true, this may present a mechanism for the inhibition of T-cell development by Spi-B, because GATA-3 is required for T-cell development.20 Experiments to test this possibility are currently underway.

We thank Dr F. Moreau-Gachelin for the polyclonal anti–Spi-B antibody and the ΔSpi-B cDNA and Dr Chiara Bonini for her gift of ΔNGFR cDNA. Dr J. Plum is thanked for the gift of the MS-5 cells. We thank Arjen Bakker and Maho Nagasawa for construction of the LZRS Spi-B IRES GFP and LZRS ΔSpi-B IRES GFP plasmids. Erik Noteboom and Anita Pfauth are acknowledged for their help with FACS sorting. The Bloemenhove Clinic in Heemstede, The Netherlands is thanked for providing fetal tissue. We thank the departments of surgery of the AMC, Amsterdam and LUMC Leiden Netherlands for making postnatal thymic tissue available.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 19, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0438.

Supported by the Netherlands Organization for Science (NWO) grant 805.17.531 and by a grant from the Foundation Marcel Mérieux, Lyon, France (to N.B.-V.).

R.S. and M.-C. R. contributed equally to this work.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Hergen Spits, Department of Cell Biology and Histology, Academic Medical Center of the University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15.1105 AZ, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail:hergen.spits@amc.uva.nl.

![Fig. 6. Effect of Spi-B on T and pDC development in vivo. / CD34+CD38− fetal liver cells were transduced with control-IRES-ΔNGFR and Spi-B-IRES-GFP. After transduction the cells were mixed 1:1 and in total 1 × 106 cells were injected into the thymus transplanted subcutaneously 8 weeks prior to injection of the transduced cells. Two weeks later the mice were killed, the thymus was removed, and single-cell suspensions were made by gently cutting the thymus and pressing the fragments through a stainless sieve. The cells were stained with antibodies against the NGFR, CD123, CD4, CD8, CD45RA, BDCA2, and HLA-DR. We excluded the cells expressing extremely high levels of CD4 and CD123 (CD4+CD123+ cells [8%]) because they may represent an artifact.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/3/10.1182_blood-2002-02-0438/4/m_h80333763006.jpeg?Expires=1769255597&Signature=sPA3oqOqVnSB3xtms8hVQcZ4vGVicCWkmriWPIJrz7wlE-q5UI2V5qewn7c2kpdFM~E9PDOYQdzVxHpw7SKciQkOR53u~QVQfriIbTZoAy0X-R2clq5u8gDPFr8tUzJa2AWo~5W75ZkLEMP1PfcY97lIZfnST922dI72msGWoHpmvr7O4mEbFjL4dMZTkiYJ1weuclq2hgeVrfoqGgfeHnvCgJFmnIk~ilbwak9mpersx9sSJosOqXh8PoGasDLMOp8nKtSBkazAGAUTo5Wi9OwvMEAQNFh1Sc1qcuMb6C1~uNp1~REhgjHMc1WX~HYj7JouVDo04VnsmfV0WxRo9Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)