Abstract

Although dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells involved in numerous physiologic and pathologic processes, little is known about the signaling pathways that regulate DC activation and antigen-presenting function. Recently, we demonstrated that nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation is central to that process, as overexpression of IκBα blocks the allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR), an in vitro model of T-cell activation. In this study, we investigated the role of 2 putative NF-κB–inducing components, NF-κB–inducing kinase (NIK), and IκB kinase 2 (IKK2). Using an adenoviral gene transfer method to efficiently express dominant-negative (dn) forms of these molecules in monocyte-derived DCs, we found that IKK2dn but not NIKdn inhibited the allogeneic MLR. When DCs were fixed, this inhibitory effect of IKK2dn was lost, suggesting that IKK2 is involved in T-cell–derived signals that enhance DC antigen presentation during the allogeneic MLR period and does not have an effect on viability or differentiation state of DCs prior to coculture with T cells. One such signal is likely to be CD40 ligand (CD40L), as IKK2dn blocked CD40L but not lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–induced NF-κB activation, cytokine production, and up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and HLA-DR in DCs. In summary, our results demonstrate that IKK2 is essential for DC activation induced by CD40L or contact with allogeneic T cells, but not by LPS, whereas NIK is not required for any of these signals. In addition, our results support IKK2 as a potential therapeutic target for the down-regulation of unwanted immune responses that may occur during transplantation or autoimmunity.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are bone marrow–derived cells that constantly circulate from the tissues to the secondary lymphoid organs, where they activate antigen-specific T cells and initiate adaptive immunity to the antigens recognized.1Their unique T-cell stimulatory capacity is due to the expression of high levels of costimulatory molecules that include CD40, CD80, and CD86, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II antigens that are essential for the presentation of endogenous and exogenous protein antigens and the production of T-cell stimulatory cytokines such as interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-15, and IL-18.1-4

DCs are believed to play a major role in transplant (allograft) rejection by presenting alloantigens to T cells,5 whose recognition of foreign MHC molecules is the primary event initiating allograft rejection. Both donor-derived and infiltrating recipient-derived DCs that take up alloantigen have been shown to activate T cells by migrating to lymphoid tissues.5,6 T cells, in turn, initiate an inflammatory process by the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and the induction of cytotoxic lymphocytes, ultimately resulting in the rejection of the graft. The observation that neutralizing antibodies or fusion proteins that inhibit efficient DC costimulation by blocking CD80/86-CD28 and CD40-CD40L interactions can prevent allograft rejection in numerous models has supported the importance of DCs in that process.7 In addition, the demonstration that DCs lacking sufficient costimulatory molecule expression induce antigen-specific T-cell anergy in vitro and prolong cardiac and islet allografts in vivo8 9 has suggested that DCs also are involved in the induction of graft tolerance.

Immunosuppressive drugs commonly used in transplantation, such as corticosteroids and cyclosporin A (CsA) or tacromilus (FK506), that block T-cell receptor signaling also have been shown to affect DC differentiation and antigen presentation.10 However, the use and efficacy of these drugs is limited by their broad toxicity, especially in the long-term.11 One approach to improve the success of human allogeneic organ transplantation is to design more specific immunosuppressive drugs, targeted directly to DCs, by understanding what regulates DC antigen-presenting function. Recently, the nuclear factor (NF)–κB transcription factors have been shown to be required for efficient DC antigen-presenting function in both mouse and human DCs,12-14 but the ubiquitous involvement of NF-κB in physiologic and homeostatic processes suggests that widespread and effective inhibition of NF-κB may have hazards. Much more attractive would be the inhibition of the pathways that lead to NF-κB activation in DCs during pathologic processes but do not affect all NF-κB functions.

The activation of NF-κB is a complex process that requires the action of multiple kinases that ultimately result in the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB proteins and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. The IκB kinases 1 and 2 (IKK1 and IKK2) that directly phosphorylate IκBα and IκBβ have been demonstrated to be important in that process in response to various inflammatory signals in vitro.15-18 IKK2, in particular, was suggested to be more important in the signaling of inflammatory mediators such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and IL-1,16,17,19-27 whereas IKK1 recently was suggested to be more important in development, probably through an NF-κB–independent role.28,29 Another important kinase proposed to act upstream of the IKKs is NF-κB–inducing kinase (NIK).30 NIK has been reported to play a major role in NF-κB activation in response to TNFα, IL-1, and LPS, and to be a key element in the activation of the IKK complex.31However, some recent studies in NIK-deficient mice and human primary cells have questioned its physiologic role in NF-κB activation in response to a variety of stimuli and have suggested that its function may be restricted to signaling through the lymphotoxin β receptor.32-34 Currently, it is not known whether IKK2 or NIK are involved in the activation of NF-κB in DCs that is essential for effective antigen-presenting function.

In this study, we adapted an adenoviral gene transfer technique to efficiently infect more than 95% of immature monocyte-derived DCs.35-37 Using this tool, we investigated the role of IKK2 and NIK in the allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR), an in vitro model of T-cell activation that takes place during allograft rejection. We report here that IKK2 but not NIK is essential for the allogeneic MLR, and we suggest that this may involve T-cell–derived signals such as CD40L that enhance DC antigen-presenting function.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Human recombinant granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was a kind gift of Dr G. Larsen (Genetics Institute, Boston, MA). Human recombinant IL-4 and soluble noncovalent trimeric CD40L were purchased from Peprotech (London, United Kingdom). Escherichia coli LPS and lipid A were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO), and the mock control and CD40L-transfected mouse fibroblast cell lines were obtained from Prof D. Gray (United Kingdom) and Prof A. Schimpl (Germany).

Isolation of peripheral blood monocytes

Peripheral blood T cells and monocytes were isolated from single donor–platelet pheresis residues of healthy volunteers and purchased from the North London Blood Transfusion Service (Colindale, United Kingdom). Mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll/Hypaque centrifugation (specific density, 1.077 g/mL; Nycomed Pharma A.S., Cheshire, United Kingdom) prior to cell separation in a Beckman JE6 elutriator (Torrence, CA). Elutriation was performed in RPMI 1640 containing 1% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (BioWhittaker, Berkshire, United Kingdom). Monocyte purity was always assessed by flow cytometry. Typical T-cell fractions contained more than 80% CD3-expressing cells, less than 5% CD19-expressing cells, and less than 1% CD14-expressing cells, whereas monocyte fractions contained 85%-90% CD14-expressing cells, less than 0.5% CD19-expressing cells, and less than 3% CD3-expressing cells.

Cell culture

Transfected mouse fibroblasts were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 1% heat-inactivated FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (BioWhittaker). Dendritic cells were generated from peripheral blood monocytes after 5 days of culture in RPMI 1640 containing 5% heat-inactivated FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 50 ng/mL GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL IL-4. At day 3 of culture, GM-CSF and IL-4 were replenished. This method is well established to produce dendritic cells of the immature phenotype and presents several advantages when compared to differentiation of dendritic cells directly from blood or bone marrow precursors. Besides being relatively easy and giving high numbers of cells, it generates a homogenous population of cells with a stable “immature DC” phenotype.13 35-37

Adenoviral vectors and their propagation

Recombinant, replication-deficient adenoviral vectors encoding the E coli β-galactosidase protein (Adβ-gal) or having no insert were provided by Drs A. Byrnes and M. Wood (Oxford, United Kingdom). An adenovirus encoding the jellyfish green fluorescence protein (GFP) (AdGFP) was provided by Quantum Biotech (Carlsbad, AB Canada), and adenoviruses encoding IκBα, (AdIκBα), or a kinase-defective dominant negative form of IKK2 (AdIKK2dn) were a kind gift of Dr R. de Martin (University of Vienna, Austria). Finally, adenoviruses encoding wild-type forms of IKK2 (AdIKK2wt) and NIK (AdNIKwt) or a kinase-defective dominant negative version of NIK (AdNIKdn) were constructed by us. All viruses are E1/E3-deleted, belong to the Ad5 serotype, and have been used previously in other studies.33,38,39 Briefly, viruses were propagated in the 293 human embryonic kidney cell line (ATCC, Middlesex, United Kingdom) and were purified by ultracentrifugation through 2 cesium chloride gradients. Titers of viral stocks were determined by plaque assay in 293 cells as previously described.40

Gene transfer into monocyte-derived DCs

After 5 days of culture in GM-CSF and IL-4, monocyte-derived DCs were collected, counted, and replated at 1 × 106cells/mL in serum-free RPMI 1640 in 48- or 96-well plates (Falcon, Oxford, United Kingdom), depending on the purpose of the experiment. Cells were then infected with replication-deficient adenoviruses at various multiplicities of infection (MOI) for 2 hours. Subsequently, the adenovirus-containing medium was removed, RPMI 1640 containing 5% heat-inactivated FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 50 ng/mL GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL IL-4 was added back, and cells were left to overexpress the transgene of interest for another 1-2 days before further use.

Analysis of infectibility

DCs left uninfected or infected with Ad0 or Adβ-gal at various MOI were collected, washed in 750 μL staining solution (phosphate-buffered saline containing 4% FCS and 10 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid]) and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes. They were then incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes before the addition of 50 μL of a 2 mM solution of fluorescein di-(β-D)–galactopyranoside (FDG; Sigma), a β-galactosidase substrate that fluoresces after the reaction takes place. After 1 minute, the reaction was stopped by addition of excess ice-cold staining solution (500 μL). Cell fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry on a Becton Dickinson FACScan (Oxford, United Kingdom). When DCs were infected with AdGFP, fluorescence was visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Nikon, Japan).

Analysis of cell death

Uninfected or adenovirus-infected DCs were cultured for 2 days in complete medium prior to being transferred to a 50 μg/mL solution of propidium iodide (PI) before analysis by fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanner (FACS).41 Late apoptotic or dying cells are PI+. The methyl-thiazol tetrazolium (MTT) assay was also used for the same purpose as previously described (Sigma).42 Analysis of early apoptosis was done by annexin V staining and examination by FACS.43

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

To assay the immunostimulatory capacity of monocyte-derived DCs, uninfected or adenovirus-infected DCs were cultured in graded doses with 1 × 105 allogeneic elutriated T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate (Falcon). Proliferation was measured on day 5 by thymidine incorporation after a 16-hour pulse with [3H] thymidine (0.5 μCi/well [0.0185 MBq]; Amersham Life Science, Bucks, United Kingdom). Both irradiated (3000 rad from a 137Cs source) and nonirradiated DCs were used, with no significant differences observed. In some experiments with uninfected DCs, a neutralizing anti-CD40L antibody (Alexis, Nottingham, United Kingdom) or a murine anti–human IgG1 isotype control was added at a concentration of 10 μg/mL to the allogeneic MLR cultures.

Western blotting and electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Two days after infection, 5 × 106 DCs were stimulated with either LPS for 30 minutes or CD40 ligand for 45 minutes. Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared as described.44 Cytosolic proteins were subsequently separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting. The antibody for β-galactosidase was from Roche Molecular Diagnostics (East Sussex, United Kingdom), and the antibodies for IKK2 and IκBα were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). In some cases, immunoprecipitations directed toward flag-tagged NIK or IKK2 were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using 10 μL anti–flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma). Nuclear extracts (10 μg) were examined for NF-κB DNA binding activity by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as previously described.45

Analysis of cytokines

To examine their cytokine production, monocyte-derived DCs were plated at 1 × 105 cells/well in 96-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plates (Falcon) and were either left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdIKK2dn, or AdIκBα. Cells were stimulated for another 24 hours 2 days after infection with 30 μg/mL soluble CD40L, 100 ng/mL LPS, or 1 μg/mL lipid A. In experiments not shown, these concentrations have been shown to induce maximal cytokine production in DCs. In some cases, 1 × 105 DCs were cocultured with 1 × 105transfected mouse fibroblasts for 24 hours. Supernatants were then collected and analyzed for TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Pharmingen, Oxford, United Kingdom), and remaining cells were examined for viability by the MTT assay as previously described (Sigma).42 ELISA plates were analyzed at an absorbance of 450 nm on a spectrophotometric ELISA plate reader (Labsystems Multiscan Biochromic, Cambridge, United Kingdom) using a DeltaSoft II.4 software program (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Results are expressed as the mean concentration of triplicate cultures ± SD.

Analysis of cell surface molecules by FACS

Cell surface molecule expression of monocyte-derived DCs was analyzed by FACS staining as previously described.14Antibodies for coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) were donated by Dr R. Finberg (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA), and antibodies for αVβ5 were provided by Drs W. Smith and J. Gamble (Hanson Centre, Adelaide, Australia). Directly conjugated antibodies for αVβ3, CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, and appropriate isotype-controls were purchased from Pharmingen.

Statistical methods

Mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), normal distribution of data, and statistical tests were calculated using GraphPad version 3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For statistical analysis, a 2-sided Student t test of paired comparisons was used.

Results

Adenoviral infection of monocyte-derived DCs

A major problem that has hampered the study of the biochemical signaling pathways involved in DC function is the difficulty of transfecting DNA into DCs.46,47 To circumvent that problem, we developed an alternative approach using replication-deficient adenoviruses. At a relatively low MOI of 300, we previously showed that mature monocyte-derived DCs can be efficiently infected to express the gene of interest14 without the need to be combined with cationic lipids.48 In this study, we modified this technique to infect immature monocyte-derived DCs, the predominant form of DCs found in tissues specialized in taking up and processing antigen.

We first examined whether immature monocyte-derived DCs express receptors involved in adenoviral infection such as the CAR, MHC class I, or the integrins αVβ3 and αVβ5.49-52 We found that although monocyte-derived DCs are not a natural target of adenoviral infection, they do express CAR and MHC class I as well as high levels of αVβ5 but negligible αVβ3 (Figure1A). This suggested susceptibility to infection, and at an MOI of 100, more than 95% of the cells expressed the bacterial protein β-galactosidase after infection with an adenoviral vector encoding the β-galactosidase gene under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter (Adβ-gal) (Figure 1B) after 1 to 2 days of culture. The presence of β-galactosidase protein was detected by addition of its substrate FDG and detection of fluorescence by FACS. Infectivity was also confirmed by using an adenoviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein (Figure 1C). Another group has also reported that replication-deficient adenoviruses infect immature monocyte-derived DCs and demonstrated that this does not perturb DC function.46

Immature DCs express CAR, MHC class I, and αVβ5, and can be efficiently infected by replication-deficient adenoviruses.

(A) Immature DCs were examined for the expression of CAR, MHC I, αVβ3, and αVβ5 by FACS staining. Cells treated with isotype control antibody (filled histogram) were compared with cells treated with αVβ5, αVβ3, CAR, or MHC class I (HLA-A, -B, -C) monoclonal antibodies (open histogram). (B) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal at various MOI, and examined after for the presence of β-galactosidase by FACS as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Immature DCs were infected with AdGFP at an MOI of 100 and then examined for the presence of GFP by fluorescence microscopy (original magnification for both panels, × 20). Representative phase-contrast and fluorescent pictures are shown. (D) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, or AdIKK2dn at an MOI of 100. After 2 days, cells were lysed and extracts examined for the presence of NIKdn or IKK2dn by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. An antibody directed against the flag epitope attached to NIKdn and IKK2dn but not β-gal was used as previously described.33 39 In all panels, the results of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

Immature DCs express CAR, MHC class I, and αVβ5, and can be efficiently infected by replication-deficient adenoviruses.

(A) Immature DCs were examined for the expression of CAR, MHC I, αVβ3, and αVβ5 by FACS staining. Cells treated with isotype control antibody (filled histogram) were compared with cells treated with αVβ5, αVβ3, CAR, or MHC class I (HLA-A, -B, -C) monoclonal antibodies (open histogram). (B) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal at various MOI, and examined after for the presence of β-galactosidase by FACS as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Immature DCs were infected with AdGFP at an MOI of 100 and then examined for the presence of GFP by fluorescence microscopy (original magnification for both panels, × 20). Representative phase-contrast and fluorescent pictures are shown. (D) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, or AdIKK2dn at an MOI of 100. After 2 days, cells were lysed and extracts examined for the presence of NIKdn or IKK2dn by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. An antibody directed against the flag epitope attached to NIKdn and IKK2dn but not β-gal was used as previously described.33 39 In all panels, the results of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

Adenoviral infection of monocyte-derived DCs resulted in the expression of high levels of kinase-deficient dominant negative forms of IKK2 (IKK2dn) and NIK (NIKdn) when AdIKK2dn and AdNIKdn were used at a MOI of 100 (Figure 1D). As a consequence of this overexpression, IKK2dn appears as a doublet, with the upper band representing the whole protein and the lower band a degradation product of it. As both antibodies used for immunoprecipitation and Western blotting are of the same species, the Ig heavy chain of the antibody used to immunoprecipitate IKK2dn and NIKdn is also shown.

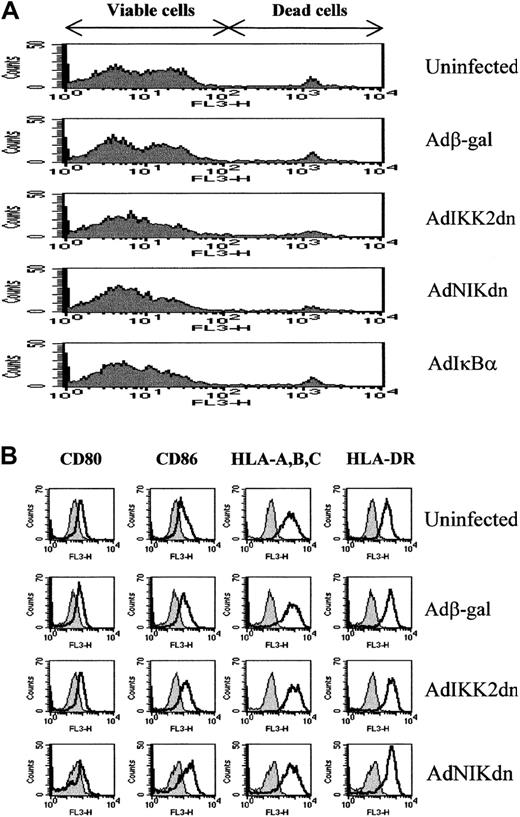

Expression of IKK2dn or NIKdn over a 2-day period prior to culture with T cells did not affect the DC viability or differentiation state. DC viability was assessed by PI staining (Figure2A) and the MTT assay as previously described (Sigma)42 (data not shown). Annexin V expression, indicative of early apoptotic events,43 revealed no difference between virus-infected cells and control uninfected cells (data not shown). DC differentiation state was assessed by examining the levels of expression of the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and the antigen-presenting molecules HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DR. These molecules are expressed in higher levels in cells of the DC phenotype compared to cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage.35-37Figure 2B (and Figure 6) shows that AdIKK2dn- or AdNIKdn-infected DCs still express similar levels of CD80, CD86, HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DR as uninfected or Adβ-gal–infected cells. This suggests that IKK2dn or NIKdn expression has no effect on the differentiation state of immature DCs.

The expression of IKK2dn or NIKdn in immature DCs does not affect their viability or differentiation state.

Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdIKK2dn, or AdIκBα at a MOI of 100. (A) After 2 days, cells were examined for viability by PI staining and FACS. Late apoptotic and dying cells stain positive in this assay. (B) After 2 days, cells were stained for cell surface expression of CD80, CD86, HLA-A, -B, -C, and DR and examined by FACS. DCs stained with isotype control (filled histograms) or specific antibody (open histograms) are compared. The results of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

The expression of IKK2dn or NIKdn in immature DCs does not affect their viability or differentiation state.

Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdIKK2dn, or AdIκBα at a MOI of 100. (A) After 2 days, cells were examined for viability by PI staining and FACS. Late apoptotic and dying cells stain positive in this assay. (B) After 2 days, cells were stained for cell surface expression of CD80, CD86, HLA-A, -B, -C, and DR and examined by FACS. DCs stained with isotype control (filled histograms) or specific antibody (open histograms) are compared. The results of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

Expression of IKK2dn but not NIKdn inhibits the allogeneic MLR

To examine the role of IKK2 and NIK activity in the allogeneic MLR, monocyte-derived DCs were infected at an MOI of 100 with replication-deficient adenoviruses encoding the protein of interest, and after further culture for 2 days they were mixed with allogeneic T cells. We found that inhibition of IKK2 activity via overexpression of IKK2dn but not of a control protein β-galactosidase abrogated the DC-induced T-cell proliferation at all DC doses used (P < .05) (Figure 3A). Overexpression, on the other hand, of NIKdn had no effect on T-cell proliferation in the allogeneic MLR, implying that NIK is not essential in this process. As expected, overexpression of IκBα also abrogated the allogeneic MLR.

The allogeneic MLR is inhibited by overexpression of IκBα or IKK2dn but not NIKdn, but this effect is lost after fixation of DCs.

Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), or AdIκBα (black). A MOI of 100 was used. (A) DCs were then plated in graded doses with 105 purified, allogeneic T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well microtiter plate. (B) DCs were first fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and then plated in graded doses with 105 purified, allogeneic T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well microtiter plate. Proliferation was determined on day 6 using the [3H]thymidine uptake assay. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from 5 (A) or 4 (B) independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors. Statistical significance was assessed by using a one-tailed Student t test using uninfected cells as a control (*P < .05, **P < .01).

The allogeneic MLR is inhibited by overexpression of IκBα or IKK2dn but not NIKdn, but this effect is lost after fixation of DCs.

Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), or AdIκBα (black). A MOI of 100 was used. (A) DCs were then plated in graded doses with 105 purified, allogeneic T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well microtiter plate. (B) DCs were first fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and then plated in graded doses with 105 purified, allogeneic T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well microtiter plate. Proliferation was determined on day 6 using the [3H]thymidine uptake assay. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from 5 (A) or 4 (B) independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors. Statistical significance was assessed by using a one-tailed Student t test using uninfected cells as a control (*P < .05, **P < .01).

The inhibition of immature DC-induced T-cell proliferation by IKK2dn and IκBα could be due to an effect on the differentiation or antigen presentation ability of DCs that occurs either before or during the coculture period with T cells. To distinguish between the 2 possibilities, we used fixed DCs that can also induce allogeneic T-cell proliferation, although much less pronounced than that observed with nonfixed DCs.53 We found that fixation of DCs prior to culture with T cells abolished the inhibitory effect of IKK2dn or IκBα overexpression in the allogeneic MLR (Figure 3B). As expected, β-galactosidase or NIKdn expression did not affect this process either. These data are in agreement with the observation that the differentiation state of immature DCs as assessed by expression of costimulatory (CD80, CD86) and antigen-presenting (HLA-DR, HLA-A, -B, -C) molecules is not affected by IKK2dn (Figures 2B and 6) or IκBα (Figure 6). In addition, these data suggest that IKK2dn and IκBα inhibit the allogeneic MLR by blocking a T-cell–derived signal during the coculture period that enhances DC antigen-presenting function.

IKK2dn inhibits CD40L but not LPS-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production, whereas NIKdn has no effect

We decided then to examine whether IKK2 or NIK is involved in DC activation induced by CD40L and LPS. These stimuli are known to enhance DC antigen-presenting function and T-cell stimulatory capacity by inducing cytokines and by up-regulating antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules.54,55 In addition, CD40L has been shown previously to be essential for the allogeneic MLR in vitro.56 We have also confirmed this in our system by using an anti-CD40L antibody that we previously showed blocks CD40L-induced activation of the endothelium57 (Figure4A).

IKK2dn DC blocks CD40L-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production in immature DCs.

Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), or AdIκBα (black), and cultured for 2 additional days. (A) Graded doses of uninfected cells were cultured with 105 allogeneic T cells in the presence of a neutralizing CD40L antibody or its isotype-matched control. Proliferation was determined on day 6 using the [3H]thymidine uptake assay. (B-D) Cells were stimulated for 24 hours with irradiated 1 × 105 mock control– or CD40L-transfected mouse fibroblasts, and supernatants were collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 4 independent experiments are shown. (E) Cells were stimulated with 30 μg/mL of sCD40L for 45 minutes, cytosolic and nuclear extracts collected, and IκBα levels as well as NF-κB DNA-binding activity were determined by Western blotting and EMSA, respectively. (F) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdNIKwt, or combinations of them. An MOI of 100 was used for each virus except in the 2 coinfection conditions, where an MOI of 500 was used to provide a 5-fold excess of Adβ-gal or AdNIKdn virus. After further stimulation for 24 hours, supernatants were collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

IKK2dn DC blocks CD40L-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production in immature DCs.

Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), or AdIκBα (black), and cultured for 2 additional days. (A) Graded doses of uninfected cells were cultured with 105 allogeneic T cells in the presence of a neutralizing CD40L antibody or its isotype-matched control. Proliferation was determined on day 6 using the [3H]thymidine uptake assay. (B-D) Cells were stimulated for 24 hours with irradiated 1 × 105 mock control– or CD40L-transfected mouse fibroblasts, and supernatants were collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 4 independent experiments are shown. (E) Cells were stimulated with 30 μg/mL of sCD40L for 45 minutes, cytosolic and nuclear extracts collected, and IκBα levels as well as NF-κB DNA-binding activity were determined by Western blotting and EMSA, respectively. (F) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdNIKwt, or combinations of them. An MOI of 100 was used for each virus except in the 2 coinfection conditions, where an MOI of 500 was used to provide a 5-fold excess of Adβ-gal or AdNIKdn virus. After further stimulation for 24 hours, supernatants were collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

For CD40L-induced DC activation, we used a commercially available trimeric soluble recombinant CD40L (sCD40L) or mouse fibroblasts transfected with either a plasmid-expressing CD40L or an empty plasmid that served as a control.58 DCs again were either left uninfected or infected with the replication-deficient adenovirus of interest, and after 2 days the stimulus was added in the cultures for another 24 hours. When used at a 1:1 ratio, irradiated CD40L-transfected cells but not control fibroblasts induced high levels of expression of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 (Figure 4B-D). This could be inhibited by AdIKK2dn and AdIκBα but not NIKdn, suggesting that IKK2 is essential for CD40L-induced NF-κB activation in immature DCs. Similar data were obtained with sCD40L used at a previously determined optimal concentration of 30 μg/mL (data not shown). AdIKK2dn but not AdNIKdn could also inhibit sCD40L-induced IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation as measured by the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Figure 4E). In all cases, viability of the cells was checked after collecting the supernatants by doing an MTT assay42 and was not affected (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that NIKdn could not act as a functional dominant negative inhibitor in immature DCs, coinfection experiments were performed using wild-type NIK (NIKwt) as the inducing stimulus as previously described.33 Expression of NIKwt-induced TNFα production was inhibited when NIKdn was coinfected at an equal or 5-fold excess titer (Figure 4F).

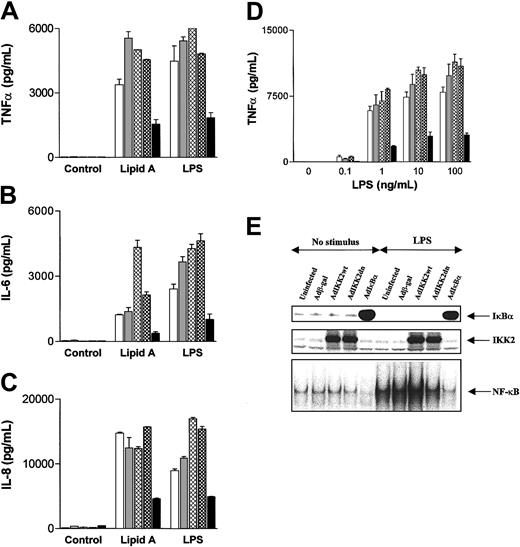

In contrast, activation of DCs with LPS or its lipid A portion induced TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 production that was not inhibited by the expression of either IKK2dn or NIKdn (Figure5A-C). This was independent of the LPS concentrations used, as at lower LPS doses TNFα (Figure 5D), IL-6, and IL-8 (data not shown) were not blocked by IKK2dn or NIKdn. The fact that LPS- or lipid A–induced DC cytokine production is not blocked further demonstrates that DC viability is not affected by the expression of IKK2dn or NIKdn. At the same time, neither AdIKK2dn (Figure 5E) nor AdNIKdn (data not shown) inhibited IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation in response to LPS or lipid A, whereas AdIκBα did (Figure 5E). These observations suggest that the involvement of IKK2 in NF-κB activation and NF-κB–dependent cytokine production in DCs depends on the stimulus, as it is required for CD40 but not for LPS receptor signaling. However, in both instances activation is NF-κB–dependent since it is blocked by IκBα overexpression. In contrast, NIK seems to be redundant with respect to NF-κB activation when LPS, CD40L, or contact with activated T cells are used as a stimulus.

Expression of IKK2dn or NIKdn into DCs does not block LPS- or lipid A–induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production.

Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), and AdIκBα (black), and cultured for 2 additional days. (A-C) Cells were stimulated for 24 hours with 100 ng/mL LPS or 1 μg/mL of lipid A, and supernatants collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 4 independent experiments performed on samples from from unrelated donors are shown. (D) Cells were stimulated with various concentrations of LPS, and supernatants collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown. (E) After stimulation with 100 ng/mL LPS for 45 minutes, cytosolic and nuclear extracts were collected. The presence of cytosolic IKK2 and IκBα was examined by Western blotting and the nuclear NF-κB DNA binding activity determined by EMSA.

Expression of IKK2dn or NIKdn into DCs does not block LPS- or lipid A–induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production.

Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), and AdIκBα (black), and cultured for 2 additional days. (A-C) Cells were stimulated for 24 hours with 100 ng/mL LPS or 1 μg/mL of lipid A, and supernatants collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 4 independent experiments performed on samples from from unrelated donors are shown. (D) Cells were stimulated with various concentrations of LPS, and supernatants collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown. (E) After stimulation with 100 ng/mL LPS for 45 minutes, cytosolic and nuclear extracts were collected. The presence of cytosolic IKK2 and IκBα was examined by Western blotting and the nuclear NF-κB DNA binding activity determined by EMSA.

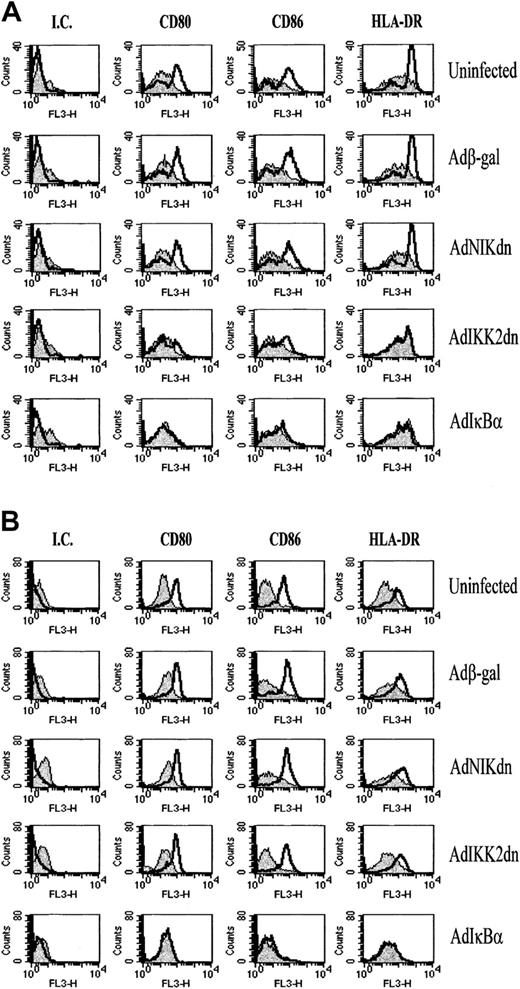

IKK2dn blocks CD40L but not LPS-induced up-regulation of CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR

The unique ability of DCs to stimulate T-cell responses is due in part to the high levels of costimulatory molecules that they display. For that reason we examined whether the expression of IKK2dn, NIKdn, or IκBα prevents the up-regulation of these molecules after CD40L and LPS-induced DC activation. Again, monocyte-derived DCs were infected with replication-deficient adenoviruses. After 1 day, one group of cells was left unstimulated, whereas the other was stimulated with 30 μg/mL of soluble CD40L or 100 ng/mL LPS for another 2 days, and cells were then stained for the presence of surface CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR. These markers increase upon DC activation and play a major role in enhancing the T-cell stimulatory ability of DCs.54 We found that although IKK2dn had no effect on the constitutive expression of these costimulatory molecules, it abrogated the up-regulation of CD80 (P < .05), CD86 (P < .05), and HLA-DR (P < .05) after CD40 triggering (Figure6A, Table1). In contrast, IKK2dn could not abrogate LPS-induced up-regulation of CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR (Figure6B), whereas NIKdn had no effect in the up-regulation of these molecules regardless of which stimulus was used (Figure 6A-B). At the same time, IκBα inhibited both CD40L and LPS-induced up-regulation of CD80 (P < .05 and P < .01, respectively), CD86 (P < .01 in both cases), and HLA-DR (P < .05 and P < .01, respectively) (Figure 6A-B, Table 1). Statistical significance was analyzed by using mean fluorescence intensity units from experiments from 4 independent donors and the 2-sided Student t test for parametric data. Because CD40L is a T-cell surface molecule believed to be essential for the allogeneic MLR,56 these data suggest that IKK2dn may inhibit DC antigen-presenting function during the allogeneic MLR by blocking CD4OL-induced DC activation after contact with T cells.

Expression of IKK2dn blocks CD40L-induced up-regulation of MHC antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules.

Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdIKK2dn, and AdIκBα. After culture for 2 additional days, DCs were stimulated for 48 hours with 30 μg/mL of sCD40L (A) or 100 ng/mL LPS (B) and then examined for the expression of CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR by FACS staining. Unstimulated DCs (filled histogram) were compared with sCD40L or LPS-stimulated DCs (open histogram) treated with isotype control (IC), CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies. The results of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

Expression of IKK2dn blocks CD40L-induced up-regulation of MHC antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules.

Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdIKK2dn, and AdIκBα. After culture for 2 additional days, DCs were stimulated for 48 hours with 30 μg/mL of sCD40L (A) or 100 ng/mL LPS (B) and then examined for the expression of CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR by FACS staining. Unstimulated DCs (filled histogram) were compared with sCD40L or LPS-stimulated DCs (open histogram) treated with isotype control (IC), CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies. The results of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of transplant rejection is characterized by the activation of alloantigen-specific CD4+ T cells, the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, the formation of an infiltrate in the graft consisting of helper and cytotoxic T cells as well as macrophages, and the production of highly specific alloreactive antibodies by B cells59 that ultimately result in graft destruction. The initiation of this process requires the recognition of alloantigens by T cells. Alloantigen presentation can be mediated either “directly” by intact allo-MHC on the surface of donor DCs or “indirectly” by recipient DCs that process peptides derived from donor MHC.5 6 The aim of our study was to characterize some of the signaling pathways involved in DC alloantigen presentation in the hope that a better understanding of that process may lead to improved and less-toxic ways of preventing allograft rejection.

First, we developed an adenoviral gene transfer method to efficiently infect immature DCs. We found that immature monocyte-derived DCs express high levels of CAR, MHC class I, and the integrin αVβ5 that have been proposed to act as receptors/coreceptors for the adenoviral entry into cells. Adenoviral infection took place at relatively low MOI, with an MOI of 100 resulting in more than 95% of DCs expressing the transgene. This efficiency allows the inhibition of DC function in complex systems such as the allogeneic MLR and the examination of endogenous genes without the need to use reporter constructs.

Next, we concentrated our study on the role of intracellular signaling pathways involved in the allogeneic MLR, an in vitro model of T-cell activation that occurs during allograft rejection. Previous work from us13,14 and others12,60 has demonstrated that NF-κB activation is required for efficient DC antigen-presenting function during the allogeneic MLR, because prevention of IκBα degradation completely abrogates the allogeneic T-cell proliferation. In addition, other studies in mice have suggested that the NF-κB subunit relB is essential for effective antigen presentation of DCs,61,62 whereas c-rel is required for cross-priming of DCs to induce cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses.63To understand what regulates NF-κB in DCs, we decided to examine the involvement of IKK2 and NIK, 2 upstream kinases that have been shown to be essential for NF-κB activation in several settings.18We found that IKK2 but not NIK activity is required for effective alloantigen presentation during the MLR in vitro. Interestingly, IKK2dn did not affect the differentiation of DCs prior to coculture with T cells, which was assessed by examining the expression of antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules such as HLA-DR, HLA-A, -B, -C, CD80, and CD86, or the ability of fixed DCs to induce T-cell proliferation. This suggested that IKK2 activity is required for a T-cell–derived signal that enhances DC antigen-presenting function during the MLR rather than an effect of IKK2dn on DC differentiation prior to the coculture period. T-cell–induced DC activation in response to allo-MHC determinants during the allogeneic MLR has been described.64 65

It is very difficult to determine what activates NF-κB and enhances DC antigen-presenting function during the complex process and the complex cell interactions of the allogeneic MLR. It is considered that one of the major signals involved is CD40L expressed by T cells.66 CD40L enhances DC T-cell stimulatory ability by inducing their activation with the consequent production of cytokines and the up-regulation of antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules.54,67 Blockade of CD40-CD40L interactions prevents TH1 cytokine production and virtually abolishes cytotoxic T-cell effector generation during the primary MLR in vitro.56 Moreover, disruption of CD40-CD40L interactions abrogates the induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses in vivo.68 69 Our observation that IKK2 but not NIK is essential for CD40L-induced NF-κB activation, cytokine production, and up-regulation of the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, and HLA-DR in DCs, suggests that its major role in the allogeneic MLR could be due mainly to its ability to prevent effective CD40-CD40L interactions from taking place.

Although IKK2 is essential for allogeneic T-cell– and CD40L-induced DC activation, it is not always involved in that process, as we have found that LPS or its lipid A portion can induce NF-κB activation and cytokine production in an IKK2-independent manner. This contradicts the current belief that IKK2 is essential for LPS-induced NF-κB activation18 and suggests that at least in DCs this is not the case. In DCs, IKK2 use is receptor-restricted with CD40L and contact with allogeneic T cells inducing IKK2-dependent and LPS inducing IKK2-independent NF-κB activation. This may have potential advantages in the design of therapeutic strategies, because agents that inhibit IKK2 will not compromise the ability of the immune system to recognize and respond to the bacterial product LPS upon bacterial infections, and probably other signals too. NIK, on the other hand, is not involved in NF-κB activation in response to CD40L, contact with allogeneic T cells, or LPS stimulation in DCs. This, however, does not exclude the involvement of NIK in other yet-unidentified pathways that also lead to NF-κB activation. We33 and others32 34 have recently found evidence that NIK is essential for lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR)–induced NF-κB activation and may thus have a more restricted role in the regulation of NF-κB.

Some other interesting points arise from this study. First, NF-κB activity is not involved in the constitutive expression of antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules in immature DCs but only plays a role in their up-regulation during DC maturation. This is supported by studies that we previously performed in mature DCs, where the overexpression of IκBα down-regulates the expression of antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules only to levels found in immature DCs.13 This is in contrast to data obtained with pharmacological NF-κB inhibitors such as N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and aspirin that also decrease the cell surface expression of CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR in immature DCs,70,71 but whether this is due to a direct consequence of NF-κB activation or nonspecific effects of the inhibition of other pathways too is not clear. Certainly, in our study the specific inhibition of NF-κB through overexpression of IκBα does not have such effects (Figure 2A). Second, NF-κB is not required for survival of DCs. This confirms recent data of others that phosphatidolinositol-3-kinase and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase rather than NF-κB are required for that process.12 72

The implications of our findings are relevant clinically. The allogeneic MLR is not only a system that measures DC antigen-presenting function but also an in vitro model of allograft rejection. Although it is simplistic to believe that it reflects exactly how T-cell activation takes place early in vivo in the process of transplant rejection, its value as a tool for the study of the molecular mechanisms involved cannot be contested. Neutralizing antibodies or proteins that prevent IL-2 signaling or CD80/86-CD28 interactions that were originally shown to inhibit the allogeneic MLR73-75 also have been shown to be efficient in vivo7,76 and are beginning to enter the clinical arena.11 A humanized murine monoclonal antibody, in particular, targeted against the 55-kDa α chain of the IL-2 receptor has received approval even for its use in humans in combination with standard cyclosporin-based immunosuppressive therapy.77 Our observations thus suggest that IKK2 may be a good therapeutic target for the prevention of transplant rejection as well as other inflammatory and autoimmune diseases where DCs also are thought to play a major role by presenting antigen and initiating inappropriate inflammatory responses.78,79 In addition, DCs are known to be important in tolerance induction.80,81We recently have shown that prevention of NF-κB activation in DCs induces T-cell tolerance in vitro.13 Our observation that this process requires IKK2 suggests that inhibition of its activity also should promote tolerance that could again be beneficial in transplantation and autoimmunity.

We would like to thank Prof B. Vogelstein, Prof D. Wallach, Prof R. Hay, Dr A. Byrnes, Dr M. Wood, and Dr R. de Martin for the reagents used in this study. We would also like to thank Dr M. Osman for reading the manuscript.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 19, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1835.

Supported by the Arthritis Research Campaign (United Kingdom) and the Wellcome Trust.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Marc Feldmann, Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology Division, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine, 1 Aspenlea Rd, Hammersmith, London W6 8LH, United Kingdom; e-mail: m.feldmann@ic.ac.uk.

![Fig. 3. The allogeneic MLR is inhibited by overexpression of IκBα or IKK2dn but not NIKdn, but this effect is lost after fixation of DCs. / Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), or AdIκBα (black). A MOI of 100 was used. (A) DCs were then plated in graded doses with 105 purified, allogeneic T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well microtiter plate. (B) DCs were first fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and then plated in graded doses with 105 purified, allogeneic T cells in quadruplicate in a 96-well microtiter plate. Proliferation was determined on day 6 using the [3H]thymidine uptake assay. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from 5 (A) or 4 (B) independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors. Statistical significance was assessed by using a one-tailed Student t test using uninfected cells as a control (*P < .05, **P < .01).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/3/10.1182_blood-2002-06-1835/4/m_h80333721003.jpeg?Expires=1766418135&Signature=nF7hlPpID9qxPU3AzfWd5z9D~DBtMzTAyybFxxMPkN1jSfZ3-dMurcWWaOGV63g4O~cWi47iP7w4KeN7imAjuw2dBL7YLcHW2f29iYw~QjWk7-jgLpmjJORFVQzcaP9eo76L9gGoRdXKY0SpzP9VwS8e5dEItaRiqX5RxX6aS8k86hHDn4fGIHRJ1GAHq4X9dX~jT-r1DR2Gnsr5ukGGmqmD9QIUvnojrpfN57UrWbTHD~Ws~N~qQC25-L7cFCMdYpjSYxcs0mE2kRCerKn~-fhhP4p8Tn0PzRvOvN-titrIefrLyJumRqSP35Q641iev6vs3tZ4LPKpyhboAPsi5w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. IKK2dn DC blocks CD40L-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production in immature DCs. / Immature DCs were left uninfected (white) or were infected with Adβ-gal (gray), AdNIKdn (cross-hatched), AdIKK2dn (checkered), or AdIκBα (black), and cultured for 2 additional days. (A) Graded doses of uninfected cells were cultured with 105 allogeneic T cells in the presence of a neutralizing CD40L antibody or its isotype-matched control. Proliferation was determined on day 6 using the [3H]thymidine uptake assay. (B-D) Cells were stimulated for 24 hours with irradiated 1 × 105 mock control– or CD40L-transfected mouse fibroblasts, and supernatants were collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 4 independent experiments are shown. (E) Cells were stimulated with 30 μg/mL of sCD40L for 45 minutes, cytosolic and nuclear extracts collected, and IκBα levels as well as NF-κB DNA-binding activity were determined by Western blotting and EMSA, respectively. (F) Immature DCs were left uninfected or infected with Adβ-gal, AdNIKdn, AdNIKwt, or combinations of them. An MOI of 100 was used for each virus except in the 2 coinfection conditions, where an MOI of 500 was used to provide a 5-fold excess of Adβ-gal or AdNIKdn virus. After further stimulation for 24 hours, supernatants were collected and assayed for the presence of TNFα by ELISA. Mean values ± SDs of 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments performed on samples from unrelated donors are shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/3/10.1182_blood-2002-06-1835/4/m_h80333721004.jpeg?Expires=1766418135&Signature=GnVFVECfrGf8H81mzz70haGHPfIjAm81QelFxndMY8rh9CZjI4glGMlWETn-2DILb3aDoIvM2GAgh7iPAix4UtVf97tEZE0AIw~YiBjPMbgJ0DPZAtFWn0UuWnFFQyHQJ4YQ9sMMjj4jAb-WNQqeIaq16sTPQgkLkdtjwg5pGu1mzlO2diuAEyBJAOmIzWNklcxvDOQ0w7ZgEhIdKX4nr3s4yIisc0M7JnFTYfaeDqbR7ogP4BJ7gi9a0-XbZtWGPp2ibo741CuDmVVohduCBElc0c0tXMHlRUD2NMhWtLEjQmXakErM7AO-ni-v9P0wi3SHKDf8Y-bwsrGYpa2i0g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)