The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is an X-linked primary immunodeficiency that is caused by mutations in the recently identified WASP gene. WASP plays an important role in T-cell receptor–mediated signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. In these studies we assessed the feasibility of using retroviral gene transfer into WASP-deficient hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to rescue the T-cell signaling defect that is characteristic of WAS. Upon transplantation of WASP-deficient (WKO) HSCs that have been transduced with WASP-expressing retroviruses, mature B and T cells developed in normal numbers. Most importantly, the defect in antigen receptor–induced proliferation was significantly improved in T cells. Moreover, the susceptibility of colitis by WKO HSCs was prevented or ameliorated in recipient bone marrow chimeras by retrovirus-mediated expression of WASP. A partial reversal of the T-cell signaling defect could also be achieved following transplantation of WASP-deficient HSCs expressing the WASP-homologous protein N-WASP. Furthermore, we have documented a selective advantage of WT over WKO cells in lymphoid tissue using competitive repopulation experiments and Southern blot analysis. Our results provide proof of principle that the WAS-associated T-cell signaling defects can be improved upon transplantation of retrovirally transduced HSCs without overt toxicity and may encourage clinical gene therapy trials.

Introduction

The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is an X-linked primary immunodeficiency characterized by recurrent infections, thrombocytopenia, eczema, and predisposition to lymphoreticular malignancies.1-3 WAS results from mutations in a cytosolic protein, WASP (Wiskott-Aldrichsyndrome protein), that is expressed in cells of hematopoietic origin.4 Recently, several additional WASP family members that are more generally expressed have been identified, including N-WASP and 3 Scar1/WASP family verprolin-homologous protein (WAVE) proteins.5-7 Through interactions with a variety of other proteins, WASP family members transduce surface receptor signals to regulate the actin cytoskeleton.8 WASP contains a pleckstrin homology domain, a GTPase binding domain, a polyproline-rich region, and a verprolin/cofilin/acidic (VCA) region that mediates interactions with membrane components, Cdc42, SH3 domain–containing molecules, and the Arp2/3 complex, respectively. Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that WASP undergoes a conformational shape change by interactions with phosphoinositides and Cdc42 that permit binding and subsequent activation of the Arp2/3 complex.9-13 WASP-dependent activation of the Arp2/3 complex directly leads to actin assembly and changes in cell shape.

Early studies in WAS patients delineated characteristic immunologic abnormalities such as progressive decline in T-cell numbers, failure to produce antibodies to polysaccharide and protein antigens, and low levels of serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) (reviewed in Snapper and Rosen8). T cells from WAS patients show aberrant responses to T-cell receptor–mediated stimulation with associated abnormalities in the actin cytoskeleton while their response to nonspecific mitogens is preserved.14-16 Furthermore, abnormalities in monocyte, dendritic cell, and T-cell chemotaxis have been identified17-19 (C.K., S.B.S, unpublished data, December 1999).

The recent generation of WASP-deficient (WKO) mice has provided a murine model for the human immunodeficiency and facilitated investigation of WASP function.20 21 These mice share some, but not all, of the clinical and immunologic features that affect human patients. WKO mice are lymphopenic in the peripheral blood and only mildly thrombocytopenic with normal-sized platelets; they also develop chronic colitis. Despite normal immunoglobulin levels and normal production of specific antibodies, T cells from WKO mice are defective in T-cell receptor–induced proliferation and have aberrant regulation of the actin cytoskeleton.

Although conservative treatment such as antibiotic prophylaxis, intravenous immunoglobulin infusions, and splenectomy have prolonged life expectancy, the ultimate prognosis of WAS remains dismal. Patients with classical WAS die in the first decades of life of recurrent infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, or malignancies, whereas patients with milder variants may survive into adulthood.22 Currently, the only curative treatment for WAS consists of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).23 However, most patients do not have an HLA-matched related donor. HSC transplantation from matched unrelated or other related donors can be associated with severe and potentially lethal complications, such as infections, graft-versus-host disease, nonengraftment, and an Epstein Barr virus (EBV)–related lymphoproliferative syndrome.24 25Therefore, a safer and more effective treatment is needed.

In an attempt to develop more specific and less toxic treatment options for WAS, we have used WKO mice as a therapeutic model system to study in vivo the feasibility of retroviral gene transfer. In vitro experiments in human B-cell lines have suggested that defective actin conglomerates and abnormal expression of glycoproteins can be corrected upon retroviral gene transfer.26 27 The objective of this study was to determine whether transplantation of WASP-transduced hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) would restore the specific T-cell signaling deficiency.

Materials and methods

Animals and cell lines

All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions (Harvard Medical School Animal Facility, Boston, MA). Wild-type (WT) 129 Sv/Ev and congenic RAG-2–deficient (RAG2 KO) mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). WKO mice were bred in our facility. NIH3T3 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; CRL 1658) were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and penicillin and streptomycin (both 50 U/mL; GIBCO, Rockville, MD). The packaging cell line 293GPG28 was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, glutamine (2 mM), penicillin and streptomycin (both 50 U/mL; GIBCO), tetracycline (1 μg/mL), puromycin (2 μg/mL), and G418 (0.3 mg/mL) (all from Sigma).

Generation of retroviruses

The cDNAs encoding WASP (murine) and N-WASP (rat) were cloned into CMMP, a derivative of MFG.29 The start codon of WASP and N-WASP matched the endogenous env ATG. Bicistronic WASP-GFP, N-WASP–GFP viruses were created by insertion of the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)–green fluorescence protein (GFP) sequence from the plasmid MSCV2.2-IRES-GFP (gift from B. Sha, University of California, San Francisco, CA) downstream of the insertion site of WASP and N-WASP in CMMP. Vesicular stomatitis virus-g (VSV-G) pseudotyped retroviruses were generated by transient transfection of CMMP-based WASP-GFP, N-WASP–GFP, and GFP plasmids into the packaging cell line 293GPG, as previously described.28The supernatant was harvested daily for 5 days, subjected to ultracentrifugation, and frozen in aliquots. The viral titers of each individual batch were determined by infection of NIH3T3 cells (yielding 108 to 109 infectious particles/mL).

Transduction and transplantation of HSCs

Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were obtained from WT or WKO mice by grinding femora and tibiae of donor mice in a sterilized mortar, red blood cell (RBC)–depleted, and stained with anti–Sca-1 (phycoerythrin [PE]–conjugated and bead-conjugated) and lineage-specific antibodies (B220, CD3, GR-1, Mac-1; fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]–conjugated). Sca-1+ cells were enriched using magnetic bead cell sorting (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). Sca-1+ lin− cells were then purified on a Vantage Cell Sorter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Enriched HSCs were cultured in stem cell medium: DMEM supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, glutamine (2 mM), penicillin and streptomycin (50 U/ML, GIBCO), HEPES (4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; 10 mM), nonessential amino acids (10 mM, GIBCO), 2-mercaptoethanol (50 μM) as well as the cytokines stem cell factor (SCF; 50 ng/mL), FLT-3L (50 ng/mL), interleukin-3 (IL-3; 20 ng/mL), and IL-6 (20 ng/mL) (all from R&D, Minneapolis, MN). After 48 hours of stimulation, the cells were transduced with concentrated retrovirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 to 50 in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL).30 The progenitor cells were precooled for 30 minutes, incubated with the virus at 4°C for 1 to 2 hours, and then returned to 37°C for an additional 3 to 4 hours. The transduced progenitor cells were either transplanted on the same day or recultured for an additional 2 days. In the latter case, transduced progenitor cells were sorted for GFP expression. Recipient mice received 1450 rad total body irradiation (TBI) in 2 divided doses (lethal dose determined by dose escalation studies). The cells were washed, resuspended in Hanks balanced medium (GIBCO), and injected into the tail vein (10 000 to 50 000 cells/mouse). Mice received acidified water for 2 weeks following the stem cell transplantation to reduce the risk of peritransplant infections.

To confirm transduction of HSCs we performed secondary bone marrow transplantations. Lethally irradiated RAG2 KO mice received transplants of 5 × 106 RBC-depleted BMCs using animals that had previously received retrovirally transduced HSCs as donors. GFP was detected in reconstituted animals that had received bone marrow from all donor populations (ie, WT CMMP-GFP; WASP CMMP-GFP; WASP CMMP-IRES-GFP) confirming transduction of HSCs in the original infections.

Fluorescence-activated cell-sorter (FACS) staining and Western analysis

Single cell suspensions of lymphoid cells were prepared and stained with antibodies following standard procedures. FITC-, PE-, and Cy-Chrome–conjugated antibodies were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Immunoblotting of cellular lysates using a polyclonal antimurine WASP antibody was performed using standard procedures.31

T-cell proliferation assay

Details of the T-cell proliferation assays have been described.20 In brief, T cells were purified from peripheral lymph nodes 2 to 4 months after transplantation of transduced HSCs by magnetic sorting and removal of B cells with anti–Ig-coated Dynabeads (Dynal, Lake Success, NY). Stimulating anti-CD3 antibodies (1-12 μg/mL, Pharmingen) were allowed to bind to 96-well tissue culture plates at 37°C for 60 minutes. Cells (5 × 104) were added to anti-CD3 antibody–coated 96-well tissue culture plates in triplicates and cultured at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 15% FCS, penicillin/streptomycin (both 100 U/mL), HEPES (10 mM), nonessential amino acids (10 mM), sodium pyruvate (10mM), and 2-mercaptoethanol (50 μM). ConA and human recombinant IL-2 (both from Sigma) were added at concentrations of 5 μg/mL and 20 U/mL, respectively. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (both from Sigma) were used at 10 ng/mL and 0.5 mM, respectively. In each proliferation experiment, T cells were cultured for 48 hours, pulsed with 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) [3H]-thymidine (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) for an additional 16 hours, harvested, and analyzed for thymidine incorporation.

Histology

Colonic samples were isolated and fixed in 10% formalin. Tissue sections were embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) for histologic examination. Microscopic colitis scores were based on the extent of bowel-wall thickening (0-3 points) and lamina propria infiltration (0-3 points) for a maximum total score of 6 points. Severity of colitis was defined as mild (< 2 points); moderate (2-5 points), or severe (> 5 points). All slides were evaluated in a blinded fashion by a single pathologist (A.K.B.).

Competitive repopulation

RBC-depleted BMCs were transplanted into lethally irradiated syngeneic RAG-2 KO mice. The graft consisted of various ratios of WT and WKO BMCs: 0% WT/100% WKO, 1% WT/99% WKO, 10% WT/90% WKO, and 100%WT/0% WKO. There were 5 million cells of each combination of WT/WKO donor graft injected into 4 to 5 recipient mice. DNA from the remaining donor cells from each combination was isolated and used to confirm the contribution of WT and WKO cells in the donor cell graft. At 4 months after transplantation, animals were killed and genomic DNA was extracted from recipient lymphoid organs. All DNA samples were digested with XbaI and electrophoretically separated and blotted onto Nylon membranes according to standard techniques. The relative ratio of WT to WKO DNA was determined by Southern hybridization using a WASP cDNA probe that detected a band size of 5.5 kb and 7.5 kb, respectively.20Blots were developed in a phosphorimager and quantification of band intensity was performed using ImageQuant software (Amersham). The band intensities were normalized for background and the presence of wild-type signals contributed by RAG-2 KO recipient cells according to the following formula: (1) %WTfinal (%WT adjusted for background and for WT contribution from RAG-2 KO recipient cells) = %WT1 (%WT adjusted for background) − %WT2 (WT allele contribution from RAG-KO recipient cells). (2) %WT1 = (WT intensity − background)/[(WT intensity − background) + (KO intensity − background)]. (3) %WT2 = average residual WT band intensity of DNA samples from all RAG-2 KO mouse recipients receiving 100% KO BM cells. Although RAG-2 KO mice do not have mature lymphocytes, they contain other hematopoietic cells that express WASP. This background WT hybridization is accounted for by this calculation.

The average of all % WTfinal values was defined as 100%. The determined %WTfinal values are indicated in reference to 100%. %WTfinal values that were 2 SDs above or below the average of all %WTfinal values in that group were disregarded. Data are shown from the combination of 2 experiments yielding similar results.

Results

Construction and characterization of recombinant retroviruses

We generated a series of WASP- and N-WASP–expressing retroviral vectors using the backbone vector CMMP (Figure1A), a derivative of MFG.29To facilitate in vitro selection prior to transplantation as well as monitoring of transduced cells in vivo, we generated bicistronic versions of the vectors that contain an IRES upstream of the marker gene eGFP. Upon infection of N-WASP–deficient fibroblasts with these retroviral vectors, expression of WASP and N-WASP was confirmed by Western blotting.32 We have also confirmed that the WASP and N-WASP proteins expressed from these vectors were functional by demonstrating that they could rescue the vaccinia-associated actin-based motility defects observed in N-WASP–deficient cells.32

WASP is expressed in mature T cells from RAG-2 recipients of transplanted retrovirally transduced WKO-HSCs.

(A) Schemes of retroviral constructs used in this study. (B) Western analysis of T cells from RAG-2 recipients of transplanted (1) WT HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP; (2) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP; (3) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-WASP. WASP is expressed (arrow) in T cells in RAG-2 recipient mice that received transplants of either WT HSCs or WASP HSCs transduced with CMMP-WASP, but not CMMP-GFP. The lower panel depicts loading controls (actin staining).

WASP is expressed in mature T cells from RAG-2 recipients of transplanted retrovirally transduced WKO-HSCs.

(A) Schemes of retroviral constructs used in this study. (B) Western analysis of T cells from RAG-2 recipients of transplanted (1) WT HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP; (2) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP; (3) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-WASP. WASP is expressed (arrow) in T cells in RAG-2 recipient mice that received transplants of either WT HSCs or WASP HSCs transduced with CMMP-WASP, but not CMMP-GFP. The lower panel depicts loading controls (actin staining).

Lymphopoiesis upon transplantation of WASP-transduced HSCs

We next tested whether WKO HSCs transduced with WASP-expressing retroviruses could lead to the development of mature lymphocytes upon transplantation into irradiated recipients. Initially, we used WKO mice as recipients for these experiments; however, the radiation used for conditioning resulted in the development of severe colitis in all WKO mice, precluding their use as recipients. Therefore, congenic RAG-2-KO mice were chosen as recipients in subsequent studies. HSCs were isolated from WT and WKO mice, transduced with VSV-G pseudotyped viruses (GFP, WASP-GFP, or N-WASP–GFP), and transplanted into lethally irradiated RAG-2-KO mice.

Recipient animals were killed 2 to 6 months after HSC transplantation and intestines and lymphoid organs were harvested for further analysis. Lymphocytes obtained from animals that received transplants of WT or WKO stem cells transduced with CMMP-GFP and CMMP-WASP-IRES-GFP, respectively, revealed WASP expression (Figure 1B). As expected WASP was not detected in the progeny of WKO stem cells transduced with control CMMP-GFP (Figure 1B). Lymphocyte numbers in peripheral lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen did not differ significantly among the various groups (data not shown). Furthermore, cell-surface expression of T- and B-cell markers (T cells: Thy1; CD3, CD4, and CD8; B cells: B220, IgM) revealed normal reconstitution of the B- and T-cell compartments in all tissues examined with no evidence of abnormal expression of activation markers such as CD25 or CD69 (data not shown). We were able to follow transduced cells in the mouse using GFP as a marker gene both in control-transduced and in WASP-transduced cells. In some experiments we transplanted progenitor cells presorted for GFP expression to enhance the percentage of transgenic cells. GFP expression in lymphocytes originating from presorted transduced stem population was evident in 10% to 40% in both T and B cells after transplantation (Table 1 and Figure2). Serial transplantation of bone marrow from RAG-2–deficient chimeras confirmed successful transduction of HSCs (data not shown).

Transduced HSCs give rise to a high frequency of mature T and B cells in bone marrow chimeras.

FACS analyses were performed on splenocytes from RAG-2 KO recipients that received transplants of either WT or WKO HSCs transduced with the indicated retroviruses (presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation). GFP expression confirms that the lymphocytes arose from the transplanted HSCs. Upper and lower panels reveal the percentage of transduced T cells (Thy1+ GFP+) and B cells (B220+GFP+), respectively. Splenocytes from a naive WT mouse served as a control.

Transduced HSCs give rise to a high frequency of mature T and B cells in bone marrow chimeras.

FACS analyses were performed on splenocytes from RAG-2 KO recipients that received transplants of either WT or WKO HSCs transduced with the indicated retroviruses (presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation). GFP expression confirms that the lymphocytes arose from the transplanted HSCs. Upper and lower panels reveal the percentage of transduced T cells (Thy1+ GFP+) and B cells (B220+GFP+), respectively. Splenocytes from a naive WT mouse served as a control.

Rescue of T-cell function after transplantation of retrovirally transduced HSCs

T-cell signaling defects most likely play an important role for the immunologic abnormalities that develop in both WAS patients and in WKO mice. Since T-cell signaling defects constitute the only unequivocally identical feature shared by mice and humans with WASP deficiency, we investigated whether they were corrected in T cells isolated from recipients of retrovirally transduced HSCs.

As shown schematically in Figure 3for 2 representative experiments and summarized in Table 1, purified T cells obtained from animals that received transplants of WKO HSCs retrovirally transduced with control CMMP-GFP did not proliferate in response to CD3-mediated T-cell–receptor stimulation. In contrast, T cells from animals that received transplants of WKO stem cells retrovirally transduced with CMMP-WASP-IRES-GFP proliferated in response to anti-CD3 antibodies. As a control, T cells from all groups were shown to proliferate equally well in response to PMA and ionomycin, agents that bypass the T-cell receptor (Figure 3B). Similar results were obtained when HSCs were presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation. In some experiments, WKO HSCs were also transduced with CMMP–N-WASP–IRES-GFP to study whether overexpression of the WASP homologue N-WASP may compensate for defective WASP-expression. Overexpression of N-WASP led to a partial rescue of T-cell proliferation, suggesting that WASP and N-WASP may have overlapping functions (Table 1 and Figure 3C).

Retrovirus-mediated WASP-gene transfer rescues T-cell signaling defects in WKO mice.

Lymphocytes isolated from RAG-2 KO recipient mice that received transplants of the indicated HSCs (keys) were stimulated with either anti-CD3 antibodies (A, 0-12 mg/mL; C, 12 mg/mL) or control PMA/ionomycin (B,D). The error bars represent the standard error. Two representative experiments are shown (A-B and C-D). In the first experiment (A-B), HSCs were not presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation; in the second experiment (C-D), HSCs were presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation. Proliferation as measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation is shown on the ordinate. Equal levels of proliferation in response to PMA/ionomycin (B,D) are used as a control for cell numbers with cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibodies (A,C). Note in panels A and C that WKO cells transduced with CMMP-vectors expressing WASP-GFP but not GFP alone partially rescue the T-cell–signaling defect. N-WASP expression can also partially rescue defective T-cell signaling in WKO cells (C).

Retrovirus-mediated WASP-gene transfer rescues T-cell signaling defects in WKO mice.

Lymphocytes isolated from RAG-2 KO recipient mice that received transplants of the indicated HSCs (keys) were stimulated with either anti-CD3 antibodies (A, 0-12 mg/mL; C, 12 mg/mL) or control PMA/ionomycin (B,D). The error bars represent the standard error. Two representative experiments are shown (A-B and C-D). In the first experiment (A-B), HSCs were not presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation; in the second experiment (C-D), HSCs were presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation. Proliferation as measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation is shown on the ordinate. Equal levels of proliferation in response to PMA/ionomycin (B,D) are used as a control for cell numbers with cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibodies (A,C). Note in panels A and C that WKO cells transduced with CMMP-vectors expressing WASP-GFP but not GFP alone partially rescue the T-cell–signaling defect. N-WASP expression can also partially rescue defective T-cell signaling in WKO cells (C).

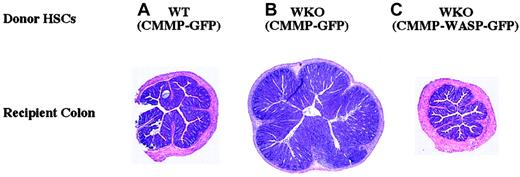

Attenuated colitis development in mice that received transplants of retrovirally transduced HSCs

Since the majority of WKO mice develop colitis by 4 months of age,20 we examined the colons of RAG-2 chimeric mice for evidence of colitis. Colitis developed in RAG-2 chimeric mice in a pattern predicted by the genotype of the transduced HSC graft (Table 1 and Figure 4). Colitis did not develop in recipients of WT-derived (CMMP-GFP–transduced) HSCs (0%; Table 2 and Figure 4). Colitis developed in the majority of recipients of WKO (CMMP-GFP–transduced) HSCs (63%; Table 2 and Figure 4). Colitis developed less frequently and was less severe in recipients receiving WKO (CMMP-WASP-GFP–transduced) HSCs (22%; Table 2 and Figure 4). These data demonstrate that WKO HSCs can lead to colitis in bone marrow chimeras and that retrovirus-mediated gene transfer of WASP in WKO HSCs can ameliorate or prevent colitis.

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer of WASP in WKO HSCs can ameliorate or prevent colitis in RAG-2 recipient mice.

Shown are representative H and E–stained cross-sections of recipient mouse colons after stem cell transplantation. (A) WT HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP: no colitis. (B) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP: severe colitis; note increased diameter due to epithelial hyperplasia and leukocyte infiltration into the lamina propria. (C) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-WASP-IRES-GFP: no colitis. Untreated RAG-KO mice do not develop colitis. Original magnification × 40 for all panels.

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer of WASP in WKO HSCs can ameliorate or prevent colitis in RAG-2 recipient mice.

Shown are representative H and E–stained cross-sections of recipient mouse colons after stem cell transplantation. (A) WT HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP: no colitis. (B) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-GFP: severe colitis; note increased diameter due to epithelial hyperplasia and leukocyte infiltration into the lamina propria. (C) WKO HSCs transduced with CMMP-WASP-IRES-GFP: no colitis. Untreated RAG-KO mice do not develop colitis. Original magnification × 40 for all panels.

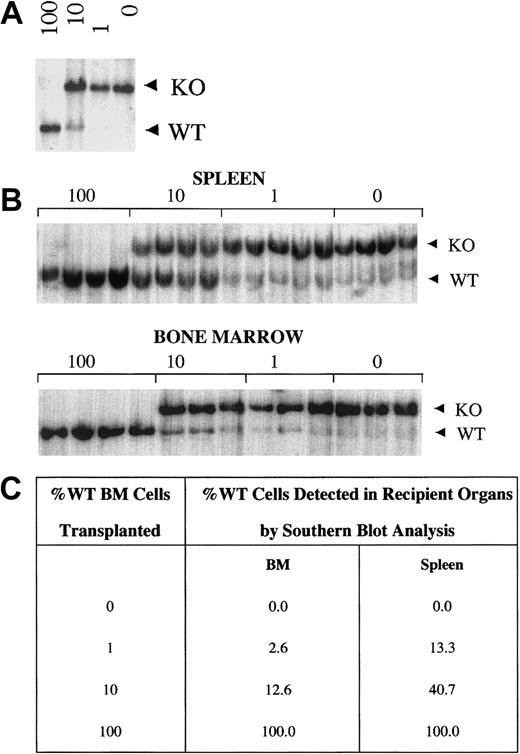

Selective advantage of WT over WKO cells in peripheral lymphoid organs

HSC gene therapy may be facilitated if there is a selective survival advantage of retrovirus-transduced cells in the recipient host. To determine whether there is a survival advantage of WASP-expressing compared with WASP-nonexpressing cells, we performed competitive repopulation experiments by transplanting various ratios of WKO and WT BMCs into RAG-KO recipient mice (Figure5). The percentage of WT to WKO cells in the donor cell population was confirmed by Southern blot analysis using a probe that distinguishes the endogenous WT gene from the targeted WKO allele (Figure 5A). Similarly, we determined the contribution of WT and WKO cells in recipient-mouse lymphoid organs 4 months after transplantation (Figure 5B). Our results show that the ratio of the WT to the targeted WKO allele in spleens (Figure 5C) and lymph nodes (data not shown) of recipient mice was significantly greater than in the donor mixed population. We were unable to appreciate a statistically significant selective advantage of WT cells over WKO cells in BM (Figure 5C) or in thymus (data not shown). In summary, these data support a selective advantage of WT over WKO cells in mature lymphocytes.

WT cells have a selective advantage over WKO cells in spleen but not in bone marrow.

(A) Southern blot analysis of DNA from mixtures of WT and WKO BMCs (100% WT, 10% WT, 1% WT, 0% WT) used as donor cells in competitive repopulation analyses. (B) Representative Southern blot analyses of bone marrow and splenic tissue DNA from recipient mice 4 months after transplantation. Each lane represents a single recipient mouse for the mixtures indicated above the blot (4-5 animals/group). WT and WKO bands (5.5 and 7.5 kb, respectively) of XbaI digested DNA are noted. (C) Densitometric quantification of Southern blots of DNA from donor cell mixtures and DNA from bone marrow and spleens of transplant recipients. WT spleen cells in recipients of 10% and 1% mixtures have a selective advantage compared with WKO cells (4- and 13-fold, respectively). Two-tailed Student t test revealed P < .0001 and P = .00067 for comparison of recipient versus donor cell population of 10% and 1% mixtures, respectively, for spleen, and P = .3 andP = .07 for comparison of recipient versus donor cell population of 10% and 1% mixtures, respectively, for BM.

WT cells have a selective advantage over WKO cells in spleen but not in bone marrow.

(A) Southern blot analysis of DNA from mixtures of WT and WKO BMCs (100% WT, 10% WT, 1% WT, 0% WT) used as donor cells in competitive repopulation analyses. (B) Representative Southern blot analyses of bone marrow and splenic tissue DNA from recipient mice 4 months after transplantation. Each lane represents a single recipient mouse for the mixtures indicated above the blot (4-5 animals/group). WT and WKO bands (5.5 and 7.5 kb, respectively) of XbaI digested DNA are noted. (C) Densitometric quantification of Southern blots of DNA from donor cell mixtures and DNA from bone marrow and spleens of transplant recipients. WT spleen cells in recipients of 10% and 1% mixtures have a selective advantage compared with WKO cells (4- and 13-fold, respectively). Two-tailed Student t test revealed P < .0001 and P = .00067 for comparison of recipient versus donor cell population of 10% and 1% mixtures, respectively, for spleen, and P = .3 andP = .07 for comparison of recipient versus donor cell population of 10% and 1% mixtures, respectively, for BM.

Discussion

Gene transfer into HSCs may offer novel therapeutic avenues for a variety of inborn errors of the hematopoietic system.33Here, we describe the use of WKO mice as a preclinical system to study the prospects of hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for WAS. We have generated WASP-expressing retroviruses and have shown that WASP-transduced WKO HSCs can differentiate into mature B and T lymphocytes in recipient mice. More importantly, we were able to document that expression of WASP rescues signaling defects in WKO T cells. Furthermore, we provide evidence that the improvement of T-cell signaling defects observed in vitro translates into substantial clinical improvement since the colitis associated with WASP deficiency is significantly ameliorated.

In some studies, ectopic WASP expression has led to dramatic changes in the actin cytoskeleton.34 These effects may have implications for the feasibility of transplantation using WASP-transduced HSCs. Consistent with our results with retrovirus-mediated gene expression of WASP (and N-WASP) in fibroblasts,32 deleterious effects were not appreciated in lymphocytes from reconstituted mice. Observations from other groups have also suggested that retrovirus-mediated WASP expression may not be toxic. Preliminary studies have demonstrated that retrovirus-mediated WASP gene transfer does not have negative effects on differentiation of human stem cells.35 Similarly, in vitro reconstitution experiments using human B-cell lines did not reveal any deleterious effects in WASP-reconstituted cells.26 27 These data, along with our in vivo experiments, argue that expression of WASP may not have to be as tightly regulated to allow appropriate function. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that in vivo selection leads only to the amplification of those lymphoid cells with adequate expression levels.

We have also demonstrated that retrovirus-mediated gene transfer of N-WASP into WKO cells can partially rescue the T-cell signaling defect. Since WT and WKO T cells express low levels of N-WASP (S.B.S., unpublished results, December 1999), the limited expression of N-WASP or one of its unique interactors must prevent full compensation for the missing functions of WASP in WKO cells. Other functions unique to N-WASP have been suggested. Miki et al demonstrated that N-WASP, but not WASP, can be utilized in concert with Cdc42 for filopodia generation in fibroblasts.13 In addition, N-WASP, but not WASP, can support the actin-based motility of Shigellaflexneri.32 In contrast to those unique aspects, the data presented here demonstrate that N-WASP has at least some overlapping functions with WASP in T-cell signaling.

Severe radiation-induced colitis precluded the use of WKO mice as recipients for HSC transplantation. In contrast to the mild to moderate colitis observed in many naive WKO mice,20 all irradiated mice suffered from severe colitis. Even sublethally irradiated WKO mice developed severe colonic inflammation (data not shown). While the basis for the increased colitis upon irradiation in WKO mice remains elusive, we speculate that increased intestinal inflammation may result from increased permeability of antigens or infectious agents due to a weakened intestinal barrier or altered mucosal immune homeostasis. In view of these effects, we used RAG-2-KO mice as recipients for HSC transplantation. Recent studies have demonstrated that the onset of colitis in WKO mice is strain specific since it does not occur in 129SvEV mice that have been crossed with C57B6 mice.36Therefore, identical studies could be performed in such colitis-resistant strain backgrounds. Nonetheless, since colitis has been documented in only the minority of WAS patients,37its assessment will most likely play only a minor role in future human gene therapy protocols.

We were unable to identify any adverse effects in our transplantation experiments. All of our mice that underwent transplantation showed normal numbers of B and T cells without increased expression of markers of activation. Furthermore, in more than 50 mice that underwent transplantation, no overt lymphoid malignancies were detected. While detailed studies addressing the effects of retrovirus-mediated expression of WASP on other hematopoietic cell lineages in this system are under way, we were unable to document any deleterious effects intrinsically associated with retrovirus-mediated WASP expression in all reconstituted animals.

Transplantation of retrovirally transduced HSCs is more likely to be successful if transduced HSCs and/or their progeny have a survival advantage in the recipient host. Using competitive repopulation experiments, we were able to document a significant selective advantage of WASP-expressing lymphoid cells in the spleen and lymph nodes of animals that received transplants. However, although statistically significant, the actual degree of the selective advantage of WASP-expressing cells was modest in our system. We were unable to appreciate a selective advantage of WASP-expressing cells in the bone marrow or in the thymus. While these differences may reflect a unique requirement for WASP in mature lymphoid cells that is not required in either immature lymphocytes or nonlymphoid cells, we favor the hypothesis that the techniques used were not sensitive enough to identify less pronounced differences. In this regard, recent work by our collaborators with WKO bone marrow cells and a serial transplantation approach has clearly demonstrated a survival advantage of WT compared with WKO HSCs that was evident only after 5 to 6 serial transplantations (D. Dumenil et al, written personal communication, May 2002). Our analyses were based on genomic Southern data that cannot reveal specific differences within specific cell lineages. We have used a surrogate assay to document a selective advantage of WASP-expressing cells by transplanting various ratios of WKO and WT cells. Whether genetically transduced HSCs and their progeny will show a similar advantage in a gene therapy protocol still remains to be shown. Such preclinical studies could be performed in WKO strains (eg, C57Bl6) for which congenic mice are available that allow tracking of strain-specific cells.36 Our results are consistent with emerging evidence implying a selective advantage of WASP-expressing over WASP-nonexpressing cells. First, several studies have demonstrated that heterozygous female carriers of WAS mutations show nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation in hematopoietic cells.38-41More recently, 2 groups reported that spontaneous reversions of the WASP mutation in hematopoietic cells from WAS patients led to significant somatic mosaicism in T cells but not B cells.42 43 We now extend these studies by providing direct evidence for a selective advantage of WASP-expressing cells following HSCT.

Whereas previous reports have used various in vitro models to show that retroviral infection of WASP-deficient cells can partially correct both the altered glycoprotein expression and actin rearrangements,26,27 our current study presents an in vivo approach to assess retroviral WASP-gene transfer. Moreover, we reveal for the first time the utility of gene therapy approaches to the functional correction of WASP deficiency in T cells associated with clinical improvement. In view of the recent landmark study which proved the concept of hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy in severe combine immune deficiency X (X-SCID),44 our results may encourage further clinical investigations to address the feasibility of clinical stem cell gene therapy in WAS patients.

We thank Peggy Russel for expert technical help and members of the Snapper/Alt/Mulligan laboratories for helpful discussions and advice.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 14, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1423.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL03749 (S.B.S.), AI50950 (S.B.S.), HL59561 (S.B.S., F.W.A., and F.S.R.); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (F.W.A., R.C.M., and initial support to S.B.S.); and the Massachusetts General Hospital NIH Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases DK43551 (S.B.S.). C.K. was a Scholar of the American Society of Hematology and is also supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KF0-110-1) and the Fritz-Thyssen Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Scott B. Snapper, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Blossom Street, Boston, MA 02114; e-mail:ssnapper@hms.harvard.edu.

![Fig. 3. Retrovirus-mediated WASP-gene transfer rescues T-cell signaling defects in WKO mice. / Lymphocytes isolated from RAG-2 KO recipient mice that received transplants of the indicated HSCs (keys) were stimulated with either anti-CD3 antibodies (A, 0-12 mg/mL; C, 12 mg/mL) or control PMA/ionomycin (B,D). The error bars represent the standard error. Two representative experiments are shown (A-B and C-D). In the first experiment (A-B), HSCs were not presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation; in the second experiment (C-D), HSCs were presorted for GFP expression prior to transplantation. Proliferation as measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation is shown on the ordinate. Equal levels of proliferation in response to PMA/ionomycin (B,D) are used as a control for cell numbers with cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibodies (A,C). Note in panels A and C that WKO cells transduced with CMMP-vectors expressing WASP-GFP but not GFP alone partially rescue the T-cell–signaling defect. N-WASP expression can also partially rescue defective T-cell signaling in WKO cells (C).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/6/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1423/4/m_h80634011003.jpeg?Expires=1769325995&Signature=WrDgBx~orX0IcWK5HghxOrYoSKQLi18HPgvEVekoSPy4Jr8ZPehrxu-XhnpWV1uiWOH4Tvi19JdygYU86af2d1z45s3iUrb4HLa99T70mxxShiWhh8Lv9HCkm0JGMHiO135M-ByE1~FEzZpKlCZ1onpzlMq4z97j99VpS3P6bwwo8Wwi3sCub4~p5rID1DzHOtO5DZzM8GB7086mB5AV~IWmdA2dgLpWiaAXe5tAt1RDM5gP8iPCKVoWsAMATOoY807srehYIQmzeOh1s3N3usKOCDKZd0mWv03SW3OOTcAzdgmpfYa2t1B8bmOHFTHQ53oQTFaY1E5MwpVR~K4bnQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)