Abstract

The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is an X-linked disorder characterized by immune dysfunction, thrombocytopenia, and eczema. We used a murine model created by knockout of the WAS protein gene (WASP) to evaluate the potential of gene therapy for WAS. Lethally irradiated, male WASP— animals that received transplants of mixtures of wild type (WT) and WASP— bone marrow cells demonstrated enrichment of WT cells in the lymphoid and myeloid lineages with a progressive increase in the proportion of WT T-lymphoid and B-lymphoid cells. WASP— mice had a defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus which was normalized in animals that received transplants of 35% or more WT cells. The WASP gene was inserted into WASP— bone marrow cells with a bicistronic oncoretroviral vector also encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP), followed by transplantation into irradiated male WASP— recipients. There was a selective advantage for gene-corrected cells in multiple lineages. Animals with higher proportions of GFP+ T cells showed normalization of their lymphocyte counts. Gene-corrected, blood T cells exhibited full and partial correction, respectively, of their defective proliferative and cytokine secretory responses to in vitro T-cell–receptor stimulation. The defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus was also improved in gene-corrected animals.

Introduction

The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is an X-linked recessive disease of quite variable expressivity, classically described as a triad of immunodeficiency, thrombocytopenia, and eczema.1,2 Opportunistic infection, hemorrhage, or malignancies are the most frequent causes of death of affected males, who rarely survive beyond the age of 20 years.3 Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be curative, but most patients lack a suitable related or unrelated matched donor, and transplantation after the age of 5 years is associated with a poor outcome.4 Thus, alternative therapeutic approaches are needed.

The gene affected by mutations in patients with WAS encodes a 54-kilodalton (kDa) polypeptide termed the WAS protein (WASP), which is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells.5 Functional studies suggests that WASP transmits and integrates signals arising at the cell membrane that result in shape changes or cell movement through reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton.5,6 Although defects in B-cell, macrophage, and dendritic cell function have been demonstrated,6-8 T-cell dysfunction is thought to be central to the immunodeficiency exhibited by patients with WAS. T-cell lines derived from patients with WAS exhibit impaired mitogenesis and cytokine secretion after T-cell–receptor stimulation.5 We9 and others10,11 have recently shown that these defects, which are also exhibited by primary T cells, can be corrected by oncoretroviral vector–mediated transfer of the WAS gene into T cells obtained from patients and expanded ex vivo. These results suggest that wild type (WT) or gene-corrected T cells may have a competitive repopulating advantage over WASP— T cells in vivo, a feature that would make gene therapy for WAS more likely to succeed.

Two mouse strains having WASP deficiency have been created by gene knockout technology.12,13 Hemizygous deficient male (WASP—) animals of both strains exhibit T-cell functional deficiencies analogous to those observed in patients with WAS, namely, poor T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation and also moderate lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, which can be normalized by transplantation.14 The availability of a mouse model of WAS now allows the evaluation of gene therapy approaches for correction of the critical defects in hematopoietic lineages caused by deficiency of WASP. Oncoretroviral vector–mediated gene transfer has been used successfully to evaluate gene therapy strategies in several murine models of human immunodeficiencies including those caused by deficiency of the common γ-chain expressed in T-cell cytokine receptors,15,16 Jak3 kinase deficiency,17 deficiency in the zap70 protein,18 and RAG-2 deficiency.19 In human trials, gene therapy has resulted in clinical improvement in patients with deficiencies in the receptor common γ-chain20 or adenosine deaminase.21

In the present study, we determined the relative ability of bone marrow cells from WT versus WAS animals to repopulate various hematopoietic lineages in lethally irradiated WASP— recipients. We also demonstrated a defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus, which we have shown was corrected in animals having higher proportions of WT cells. A vector encoding murine WASP, when introduced into repopulating stem cells, resulted in production of the protein in hematopoietic cells with improvement of the defects in T-cell receptor–mediated mitogenesis and cytokine production. The deficiency in the T-cell response to secondary inoculation with influenza virus was also improved.

Materials and methods

Oncoretroviral vectors

The coding region of the murine WASP cDNA (a kind gift from Dr Uta Francke, Stanford University) was inserted upstream of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) element of an MSCV/IRES/GFP vector,22 yielding plasmid pMWG. VSV-G–pseudotyped oncoretroviral vector preparations were prepared by cotransfection of 293T cells with plasmid pMWG, or plasmid MG (encoding GFP with no IRES) with the packaging plasmids pEQPAM3-E and pSRαG. The resultant vector preparations were used to transduce GP+E86 cells.23 Pools of transduced GP+E86 cells were used in turn to transduce murine bone marrow cells by coculture. The vector genomes were shown to be unrearranged by Southern blot analysis of the producer lines. Conditioned media containing vector particles were titered on NIH 3T3 cells by evaluating the percentage of GFP+ cells achieved with several dilutions of the vector preparation. The titers of vector preparations ranged from 2.0 × 105/mL to 7.0 × 105/mL.

WAS knockout mice

The WASP— strain described by Snapper et al12 (129S6/SvEvTac-Wastm1Sbs) was obtained from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME. Knockout males were bred with C57Bl/6J females for 2 to 5 generations, and the progeny screened by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay or by Southern blotting as described.12 All studies were performed in hemizygous deficient (WASP—) male animals. The WASP— and C57Bl/6J strains are congenic for the H-2b major histocompatibility complex (MHC) type.

Competitive repopulation assays

All experiments involving the use of mice were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Bone marrow was harvested from Ly5.1+ donor mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ; Jackson Laboratories), WASP— mice, and WT littermate donors. Total nucleated cells were counted, and mixtures of Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WASP—) or Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WT) were prepared in various proportions. Cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% inactivated fetal calf serum (iFCS) prior to tail-vein injection into lethally irradiated WASP— recipients. Peripheral blood leukocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry using the anti-Ly5.1 antibody (antimouse CD45.1; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA).

Transduction and transplantation of bone marrow cells

Retroviral transduction of murine bone marrow cells was performed as previously described.22 Briefly, donor mice were treated with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) 48 hours prior to bone marrow harvest. Cells were harvested from the femur and tibia, and cultured for 48 hours in the presence of murine interleukin 3 (IL-3), human IL-6, and murine stem cell factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cells were then cocultured for 48 hours with irradiated (1200 cGy) producer cells in the same culture medium supplemented with polybrene (6 μg/mL). Nonadherent cells were then rinsed off the producer layer and used for transplantation. To monitor the efficiency of transduction, the fraction of GFP+ cells was determined by flow cytometry, and/or progenitor assays were performed by resuspending 1.5 × 104 marrow cells in 3 mL methylcellulose culture medium (M3434; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and plating in 35-mM dishes for 7 to 10 days. The fraction of GFP+ colonies was then assessed by fluorescent microscopy.

Bone marrow cells were resuspended in PBS containing 2% iFCS. Heparin was added to 5 U/mL of the solution, and 2 × 106 cells were injected into the tail veins of lethally irradiated (1000 cGy) WASP— recipients. At various times after transplantation, recipients were bled from the retro-orbital sinus for complete blood counts and evaluation of GFP expression in each blood cell type. Neutrophils were gated on forward versus side scatter; T cells were also gated on forward versus side scatter and stained with an anti-Thy1.2 antibody (Pharmingen), and B cells were gated by the same method using anti-B220 antibody (Pharmingen). Monocytes were gated on forward versus side scatter with back-gating to minimize T- and B-cell contamination.

T-cell function assays

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and splenocytes were obtained by passing the disrupted tissue through a 70-μm filter in “RPMI+.” The latter consists of RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (iFBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), 10 mM HEPES pH 7.0 (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 1X nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), 50 μM beta-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Each lot of iFBS was tested for its ability to support T-cell survival and/or proliferation in an influenza-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay. Following red cell lysis, B lymphocytes were removed by adsorption to antibody-coated flasks (goat antimouse IgG+IgM, Jackson Immunoresearch). Nonadherent cells were stimulated for 48 hours with anti-CD3ϵ antibody (Pharmingen) that had been adsorbed to 96-well plates (see legend to Figure 6). Assays were performed in triplicate at 2 × 105 cells per well. One μCi (0.037 MBq) methyl-3H-thymidine was added and the incubation was continued for another 24 hours before assaying 3H-thymidine incorporation.

Proliferation of splenic T cells from gene-corrected, WASP— animals in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation. As described in the text, 2 separate experiments were performed with 2 WASP— animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the MWG vector along with appropriate controls. Splenic T cells were cultured for 48 hours in 96-well dishes coated with anti-CD3 antibody (5 ng/well, overnight, 4°C [panel A]; 50 ng/well, 6 hours, 4°C [panel B]) or in untreated wells (control). 3H-thymidine was added, and 24 hours later total incorporation was measured. Each result is the mean of 3 independent measurements. The cells transplanted into the irradiated WASP— mice and vectors, if any, used for transduction are as follows: lane 1, WASP—; lane 2, WASP— and MG; lane 3, WT; lane 4, WT and mock (A) or WT and MG (B); lanes 5 and 6, 2 separate mice with WASP— cells transduced with the bicistronic MWG vector. The percentage of GFP+ T cells was measured in peripheral blood prior to the proliferation assays. Error bar equals standard error.

Proliferation of splenic T cells from gene-corrected, WASP— animals in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation. As described in the text, 2 separate experiments were performed with 2 WASP— animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the MWG vector along with appropriate controls. Splenic T cells were cultured for 48 hours in 96-well dishes coated with anti-CD3 antibody (5 ng/well, overnight, 4°C [panel A]; 50 ng/well, 6 hours, 4°C [panel B]) or in untreated wells (control). 3H-thymidine was added, and 24 hours later total incorporation was measured. Each result is the mean of 3 independent measurements. The cells transplanted into the irradiated WASP— mice and vectors, if any, used for transduction are as follows: lane 1, WASP—; lane 2, WASP— and MG; lane 3, WT; lane 4, WT and mock (A) or WT and MG (B); lanes 5 and 6, 2 separate mice with WASP— cells transduced with the bicistronic MWG vector. The percentage of GFP+ T cells was measured in peripheral blood prior to the proliferation assays. Error bar equals standard error.

For cytokine assays, postadsorption T-cell populations were cultured in RPMI+ supplemented with 300 U/mL IL-2 (Aldesleukin Proleukin; Chiron, Emeryville, CA) and phytohemaglutinin (PHA; Invitrogen, 1X) for 48 hours and then shifted overnight to RPMI+ lacking these agents. Cells (4 × 105/well) were then stimulated in duplicate with immobilized anti-CD3ϵ antibody as for the proliferation assays, but in the presence of 10 μg/mL Brefeldin-A(Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI), for 5 hours.After binding of surface markers (anti-CD4 or anti-CD8), cells were permeabilized via sequential exposure to formaldehyde (2%, 15 minutes, room temperature [RT]) and saponin (0.5%, 10 minutes; Sigma), exposed to anticytokine antibodies (interferon γ–phycoerythrin (PE); tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α]–allophycocyanin [APC]; IL-2–PE; all from Pharmingen), and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Influenza virus challenges and influenza-specific T-cell assays

Mice underwent primary intraperitoneal inoculation with 107.9 embryo infectious doses (EID50) of influenza A virus strain Puerto Rico/8/34, (hereafter, PR8). Secondary responses were generated 8 to 9 weeks later by intranasal challenge with 106.8 EID50 of strain Hong Kong X31 (hereafter, X31). This strain diverges from PR8 at epitopes responsible for humoral immunity but shares the known epitopes to which T-cell responses are targeted. Seven to 8 days after this secondary inoculation, mice were sampled. At the time of sampling, the mice were anesthetized and exsanguinated from the axillary artery. Lymphocytes were obtained from spleens by homogenization and passage of the cells through 100-μm filters in Hanks buffered saline solution. Tetramer and cytokine production assays were then performed as previously described.24-26 Briefly, splenocytes were suspended in ice-cold PBS containing bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0.1%) and azide (0.01%) and then, unless otherwise specified, stained on ice for 30 minutes with conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) supplied by Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). At this stage, cells were stained with anti-CD8–PerCP-Cy5.5 and anti-CD4–PE to determine the T-cell phenotype of the unmanipulated sample. For tetramer and cytokine secretion studies, splenocytes were enriched for the CD8+ set by in vitro depletion with mAbs to I-Ab (M5/114.15.2) and CD4 (GK1.5), using sheep anti–rat Ig and sheep anti–mouse Ig–coated magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). These CD8+ T-cell–enriched preparations were then stained with anti-CD8 (PerCP-Cy5.5) and PE-labeled tetrameric complexes (DbNP366),26 the H2Db MHC class I glycoprotein plus influenza nucleoprotein (NP366-374) peptide. For cytokine analyses, enriched CD8+ T cells were incubated with 1 μM NP peptide for 5 hours in the presence of 5 μg/mL Brefeldin A (Epicentre Technologies). The cells were fixed, stained with anti-CD8a antibody, permeabilized, and stained with the anticytokine antibodies described for the T-cell function assays (Pharmingen). Data were acquired with a Becton Dickinson FACScan or FACScalibur flow cytometer and then analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA).

Western blotting

Total proteins from cultured bone marrow cells or from peripheral leukocytes were prepared by standard methods, in all cases supplementing preparation buffers with complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). A mouse monoclonal antibody to human WASP27 was a gift from Dr David Nelson (NIH). Western blots were developed with the “supersignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate” kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Actin levels were assessed by staining parallel gels with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Sigma).

Statistical analysis

A growth curve model (mixed effects model) was used to determine if there was an improvement in T-cell/B-cell repopulation over time in the competitive repopulation experiment (Figure 1). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the percentages of CD8+ cells specific for NP antigen (Figure 2A, Figure 9A), the percentages of GFP+ cells in different lineages (Figure 5), and the percentages of CD8+ cells accumulating cytokines (Figures 2B and 9C). P values were obtained using either the exact or the Monte Carlo method. The reconstitution of NP-specific CD8+ T cells and cytokine production by NP-stimulated T cells as a function of the percentage of WT cells were assessed using a quadratic regression model (Figure 3B-C). A simple linear regression model was used to evaluate the association between the percentage of GFP+ T lymphocytes and total lymphocyte count (Figure 4). Cytokine accumulation values in Figure 8 were assessed using a mixed effects model with repeated measurements on each mouse. Since the number of mice in each group was relatively small, the P values for the comparisons were obtained by applying the permutation test.28,29 The P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed with the statistical software package SAS, Release 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

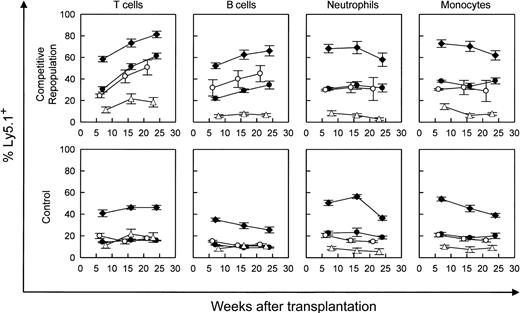

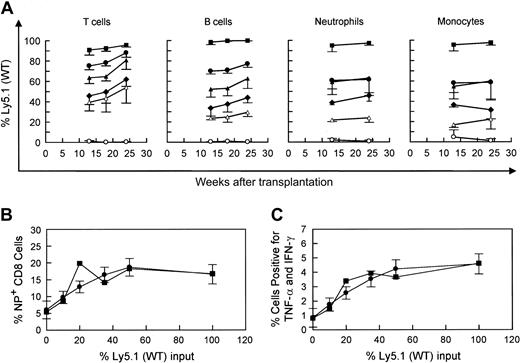

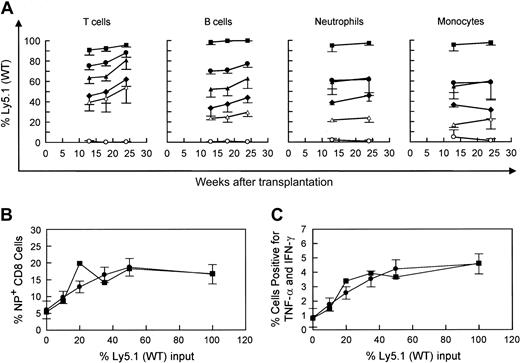

Competitive repopulation advantage of WT versus WASP— stem cells in WASP— mice following transplantation. WASP— mice received transplants of varying percentages of Ly5.1(WT) cells as follows: 10% (▵), 20% (○ and •), or 50% (♦), with the remainder of cells transplanted being Ly5.2(WASP—) cells (top row). For control mixtures, WT (littermate) Ly5.2 bone marrow cells were substituted for WASP— cells (bottom row). The mixture of 20% WT versus 80% WASP— cells was performed in 2 sets of animals. Peripheral blood was obtained at the times indicated and analyzed by flow cytometry using a monoclonal antibody specific for the Ly5.1 epitope. T-cell marker: Thy 1.2. B-cell marker: B-220. Neutrophils were gated by forward versus side scatter. Monocytes were also gated by forward versus side scatter, with backgating to minimize lymphocyte (B220+ or Thy 1.2+) contamination. Each data point represents the mean and standard errors of data obtained from 4 to 6 animals.

Competitive repopulation advantage of WT versus WASP— stem cells in WASP— mice following transplantation. WASP— mice received transplants of varying percentages of Ly5.1(WT) cells as follows: 10% (▵), 20% (○ and •), or 50% (♦), with the remainder of cells transplanted being Ly5.2(WASP—) cells (top row). For control mixtures, WT (littermate) Ly5.2 bone marrow cells were substituted for WASP— cells (bottom row). The mixture of 20% WT versus 80% WASP— cells was performed in 2 sets of animals. Peripheral blood was obtained at the times indicated and analyzed by flow cytometry using a monoclonal antibody specific for the Ly5.1 epitope. T-cell marker: Thy 1.2. B-cell marker: B-220. Neutrophils were gated by forward versus side scatter. Monocytes were also gated by forward versus side scatter, with backgating to minimize lymphocyte (B220+ or Thy 1.2+) contamination. Each data point represents the mean and standard errors of data obtained from 4 to 6 animals.

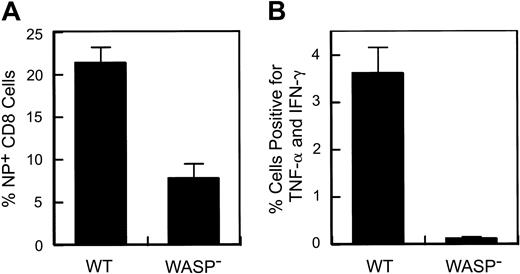

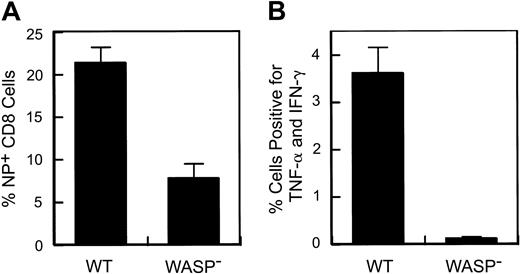

A defect in the response to secondary influenza virus challenge in WASP— animals. Eight to 9 weeks after primary intraperitoneal inoculation with influenza (PR8), animals received a secondary intranasal inoculation with strain X31. Splenic T cells were harvested 8 to 9 days later. (A) Percentage of splenic CD8+ T cells specific for the influenza NP antigen. Data are pooled from 3 separate experiments (WT: n = 10; WASP—: n = 9). (B) Cytokine production by stimulated splenic T cells. Spleen cells were cultured in the presence of Brefeldin A and NP peptide and then analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage of CD8+ cells positive for TNF-α and IFN-γ are shown (WT: n = 4; WASP—:n = 3). Error bar equals standard error.

A defect in the response to secondary influenza virus challenge in WASP— animals. Eight to 9 weeks after primary intraperitoneal inoculation with influenza (PR8), animals received a secondary intranasal inoculation with strain X31. Splenic T cells were harvested 8 to 9 days later. (A) Percentage of splenic CD8+ T cells specific for the influenza NP antigen. Data are pooled from 3 separate experiments (WT: n = 10; WASP—: n = 9). (B) Cytokine production by stimulated splenic T cells. Spleen cells were cultured in the presence of Brefeldin A and NP peptide and then analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage of CD8+ cells positive for TNF-α and IFN-γ are shown (WT: n = 4; WASP—:n = 3). Error bar equals standard error.

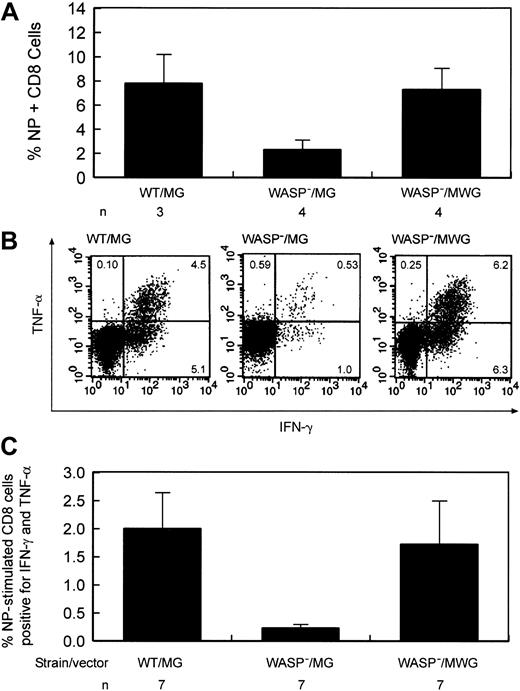

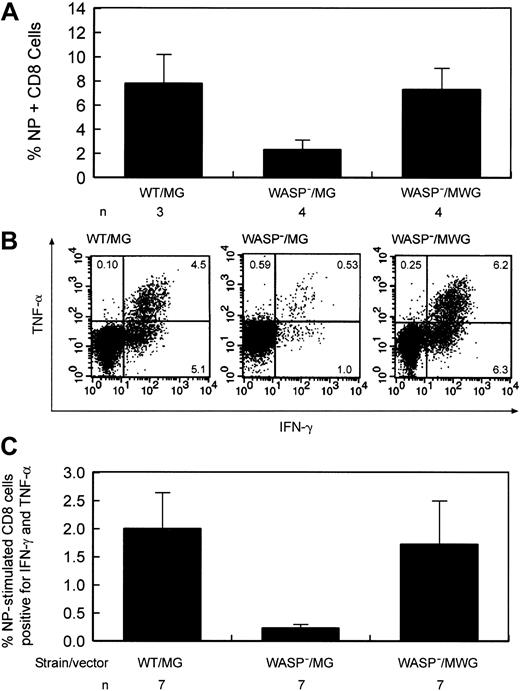

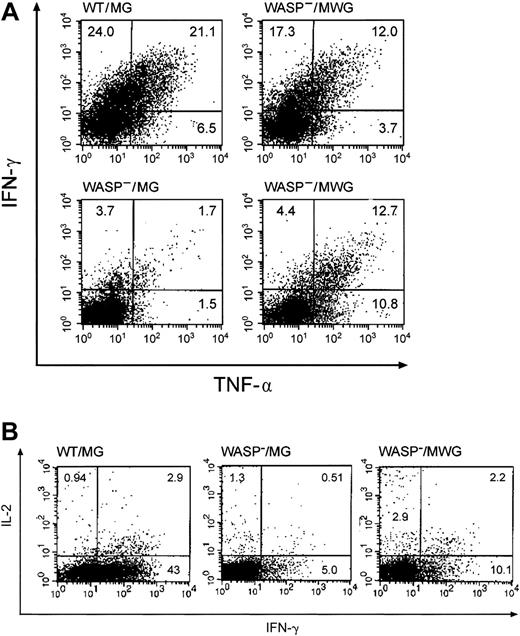

Improvement of the defect in influenza virus immunity by stem cell targeted gene transfer. (A) Percentage of splenic CD8+ T cells positive for influenza NP antigen–specific receptors following secondary influenza challenge. Eight to 9 weeks following primary inoculation,10 gene-corrected and several control animals received a secondary challenge with influenza. Eight to 9 days later, splenic T cells were harvested. WT indicates wild type; WASP—, hemizygous deficient male animal; MG, control GFP encoding vector; MWG, bicistronic vector encoding WASP and GFP; and n, number of animals in each group. The difference in the percentage of NP-specific cells between the WASP—/MG and WASP—/MWG groups is statistically significant (P < .02). (B) Cytokine production by gene-corrected and control splenic T lymphocytes after stimulation with influenza-specific NP peptide following secondary influenza challenge. Splenic CD8+ cells were cultured in the presence of Brefeldin A and NP peptide and then analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” IFN-γ and TNF-α production by stimulated CD8+ splenic T cells from a gene-corrected animal killed 9 days after secondary influenza challenge were measured as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Summary of cytokine secretion by splenic T cells of gene-corrected and control animals. Abbreviations are as defined in the legend to Figure 6. n indicates the number of animals included in each group. The difference in the percentage of double-positive cells between the WASP—/MG and WASP—/MWG groups is statistically significant (P < .03).

Improvement of the defect in influenza virus immunity by stem cell targeted gene transfer. (A) Percentage of splenic CD8+ T cells positive for influenza NP antigen–specific receptors following secondary influenza challenge. Eight to 9 weeks following primary inoculation,10 gene-corrected and several control animals received a secondary challenge with influenza. Eight to 9 days later, splenic T cells were harvested. WT indicates wild type; WASP—, hemizygous deficient male animal; MG, control GFP encoding vector; MWG, bicistronic vector encoding WASP and GFP; and n, number of animals in each group. The difference in the percentage of NP-specific cells between the WASP—/MG and WASP—/MWG groups is statistically significant (P < .02). (B) Cytokine production by gene-corrected and control splenic T lymphocytes after stimulation with influenza-specific NP peptide following secondary influenza challenge. Splenic CD8+ cells were cultured in the presence of Brefeldin A and NP peptide and then analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” IFN-γ and TNF-α production by stimulated CD8+ splenic T cells from a gene-corrected animal killed 9 days after secondary influenza challenge were measured as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Summary of cytokine secretion by splenic T cells of gene-corrected and control animals. Abbreviations are as defined in the legend to Figure 6. n indicates the number of animals included in each group. The difference in the percentage of double-positive cells between the WASP—/MG and WASP—/MWG groups is statistically significant (P < .03).

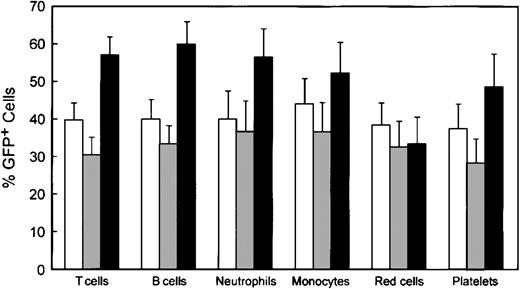

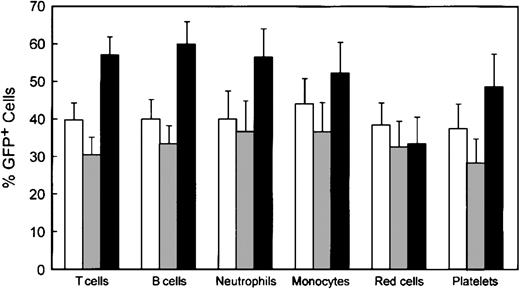

Reconstitution of various hematopoietic lineages by genetically modified cells. Data were obtained as described in the legend to Figure 4. □ indicates WT/MG (n = 14); ▦, WASP—/MG (n = 18); and ▪, WASP—/MWG (n = 18). Error bars equal standard error.

Reconstitution of various hematopoietic lineages by genetically modified cells. Data were obtained as described in the legend to Figure 4. □ indicates WT/MG (n = 14); ▦, WASP—/MG (n = 18); and ▪, WASP—/MWG (n = 18). Error bars equal standard error.

Repopulation of various hematopoietic lineages and improvement in the T-cell response to influenza following transplantation of mixtures of WT and WASP— cells in WASP— mice. (A) The percentages of Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WASP—) bone marrow cells infused were as follows: 0% (○), 10% (▵), 20% (♦), 35% (▴), 50% (•) and 100% (▪). Peripheral blood was obtained at the indicated times and analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 1 for T cells, B cells, neutrophils, and monocytes. Shown are the mean and standard errors of data obtained in 2 to 5 animals in each group. Primary challenge with influenza was given at 14 weeks and the secondary challenge was given at 23 weeks. (B) Correction of deficiency of NP-specific T cells by transplantation of WT cells. The mean value for each cohort (▪) is shown, as is the predicted value (•) and standard error calculated by a nonlinear curve-fitting method (see “Materials and methods”) (n = 2-5 animals per cohort; total = 21). (C) Cytokine production by splenic T cells after stimulation with influenza-specific NP tetramer following secondary influenza challenge. Mean (▪) and predicted (•) percentages of cells positive for TNF-α and IFN-γ were calculated as in panel B.

Repopulation of various hematopoietic lineages and improvement in the T-cell response to influenza following transplantation of mixtures of WT and WASP— cells in WASP— mice. (A) The percentages of Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WASP—) bone marrow cells infused were as follows: 0% (○), 10% (▵), 20% (♦), 35% (▴), 50% (•) and 100% (▪). Peripheral blood was obtained at the indicated times and analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 1 for T cells, B cells, neutrophils, and monocytes. Shown are the mean and standard errors of data obtained in 2 to 5 animals in each group. Primary challenge with influenza was given at 14 weeks and the secondary challenge was given at 23 weeks. (B) Correction of deficiency of NP-specific T cells by transplantation of WT cells. The mean value for each cohort (▪) is shown, as is the predicted value (•) and standard error calculated by a nonlinear curve-fitting method (see “Materials and methods”) (n = 2-5 animals per cohort; total = 21). (C) Cytokine production by splenic T cells after stimulation with influenza-specific NP tetramer following secondary influenza challenge. Mean (▪) and predicted (•) percentages of cells positive for TNF-α and IFN-γ were calculated as in panel B.

WASP expression and lymphocyte counts following transplantation of WASP— stem cells transduced with the MWG vector. (A) Western blot analysis was performed on extracts of peripheral blood leukocytes from WT and WASP— mice (left 2 lanes), 2 mice that received transplants of WT cells cocultured with 3T3 (M = mock) rather than vector producer cells, 2 animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the control vector (MG), and 3 animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the WASP expression vector (MWG) shown. The same extracts run on a parallel gel were analyzed for actin levels as a control for loading comparability among the lanes. The percentage of GFP+ lymphocytes are given for the animals that received transplants of transduced bone marrow cells. The FACS analysis was performed and extracts were prepared 20 weeks after transplantation. (B) Total lymphocyte counts plotted as a function of the percentage of GFP+ T lymphocytes for individual mice. Data are pooled from 4 separate experiments. Animals in the experimental cohort and the 2 control cohorts that did not have more than 1% of GFP+ cells in at least one lineage were excluded from the analysis. Blood was obtained for flow cytometric analysis and complete blood count at 14 to 24 weeks after transplantation. (C-D) Corresponding data from the control cohorts of mice. Best-fit linear regression curves are shown.

WASP expression and lymphocyte counts following transplantation of WASP— stem cells transduced with the MWG vector. (A) Western blot analysis was performed on extracts of peripheral blood leukocytes from WT and WASP— mice (left 2 lanes), 2 mice that received transplants of WT cells cocultured with 3T3 (M = mock) rather than vector producer cells, 2 animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the control vector (MG), and 3 animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the WASP expression vector (MWG) shown. The same extracts run on a parallel gel were analyzed for actin levels as a control for loading comparability among the lanes. The percentage of GFP+ lymphocytes are given for the animals that received transplants of transduced bone marrow cells. The FACS analysis was performed and extracts were prepared 20 weeks after transplantation. (B) Total lymphocyte counts plotted as a function of the percentage of GFP+ T lymphocytes for individual mice. Data are pooled from 4 separate experiments. Animals in the experimental cohort and the 2 control cohorts that did not have more than 1% of GFP+ cells in at least one lineage were excluded from the analysis. Blood was obtained for flow cytometric analysis and complete blood count at 14 to 24 weeks after transplantation. (C-D) Corresponding data from the control cohorts of mice. Best-fit linear regression curves are shown.

Summary of cytokine production studies of splenic T cells following gene correction. Included in the positive control group were WT mice that did not receive transplants and animals that received transplants of WT cells cocultured with 3T3 cells (M) or cells producing the control MG vector. WASP— mice and WASP— mice that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the control MG vector were included in the negative control group. Within each control group and the experimental group, 4 mice were included for the measurements of IL-2 and IFN-γ and 2 for the measurements of TNF-α. The measurements of IL-2 in the CD4 cells for 2 animals were not included in the analysis because of experimental technical difficulties. Spleen cells were stimulated with anti-CD3. For each mouse, assays were performed in duplicate (IL-2, TNF-α)or quadruplicate (IFN-γ). The values shown are the means and standard errors of the average of the measurements in the individual mice. In all cases, cytokine production by the gene-corrected cells was greater than that for the negative controls. When 4 animals were included in the analyses, namely for IFN-γ and IL-2 in CD8 cells and IFN-γ in CD4 cells, the differences between WASP— and WASP—/MWG were statistically significant (P < .05).

Summary of cytokine production studies of splenic T cells following gene correction. Included in the positive control group were WT mice that did not receive transplants and animals that received transplants of WT cells cocultured with 3T3 cells (M) or cells producing the control MG vector. WASP— mice and WASP— mice that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the control MG vector were included in the negative control group. Within each control group and the experimental group, 4 mice were included for the measurements of IL-2 and IFN-γ and 2 for the measurements of TNF-α. The measurements of IL-2 in the CD4 cells for 2 animals were not included in the analysis because of experimental technical difficulties. Spleen cells were stimulated with anti-CD3. For each mouse, assays were performed in duplicate (IL-2, TNF-α)or quadruplicate (IFN-γ). The values shown are the means and standard errors of the average of the measurements in the individual mice. In all cases, cytokine production by the gene-corrected cells was greater than that for the negative controls. When 4 animals were included in the analyses, namely for IFN-γ and IL-2 in CD8 cells and IFN-γ in CD4 cells, the differences between WASP— and WASP—/MWG were statistically significant (P < .05).

Results

Competitive repopulation of WT versus WASP— cells after bone marrow transplantation

Our WASP— mice on the C57/Bl6J background express the Ly5.2 epitope of the CD45 leukocyte surface marker. Utilizing an otherwise congenic strain expressing Ly5.1, we performed bone marrow transplantation on lethally irradiated WASP— mice with a range of mixtures of Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WASP—) donor marrow cells (Figure 1). Parallel mixtures of Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WT) donor marrow cells served as controls. The WASP— mice used in these experiments were from the second and third generations of serial cross breeding begun with hemizygous-deficient males from the original (129 SVEV) WASP— strain that were bred with C57Bl/6J females. The WASP— and C57B1/6J strains are congenic for the H-2b MHC type. The results demonstrate a significant, progressive repopulating advantage for WT-derived T cells over WASP— T cells (Figure 1). WT-derived B cells showed a similar advantage. Specifically, the positive slope of each plot is significant (P < .0001), except for the 10% WT cohort. A modest relative enhancement of engraftment of the neutrophil and myeloid lineages by WT cells was also seen. The 50:50 mixtures yielded 60% to 70% WT cells and the 20:80 WT-WASP— mixture yielded 30% to 40% WT cells in these lineages at 7 weeks without subsequent enrichment (Figure 1).

Defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus infection in WASP— mice is corrected by WT cells

Following influenza virus inoculation, mice generate CD8+ T cells specific for a number of influenza epitopes. The most prominent of these is the nucleoprotein (NP) epitope NP366-374.26 We have observed no deficiency in the generation of NP-specific T cells by WASP— mice after primary inoculation with influenza virus (data not shown). However, when we examined the memory (or secondary) response of previously inoculated WASP— mice to a second inoculation, we found a substantial reduction in the number of splenic NP-specific CD8+ cells generated in WASP— mice in comparison to WT controls (Figure 2A); 21% ± 1.9% in WT versus 7.8% ± 1.7% in the WASP— animals (P < .0001). We also found that cytokine production by CD8+ T cells, after in vitro stimulation with NP antigen, was markedly reduced in WASP— mice (P < .03) (Figure 2B). TNF-α and interferon γ (IFN-γ) were studied because their production has been well characterized in the presence of influenza virus infection.30

The competitive repopulation assay described in the previous section, “Competitive repopulation of WT versus WASP— cells after bone marrow transplantation,” was repeated with fractions of Ly5.1(WT) marrow cells ranging from 0% to 100%. The WASP— donors and recipients in these experiments were fourth to fifth generation backcrosses of WASP— male mice with C57Bl/6J females. Following infusion of cells into lethally irradiated WASP— recipients, the mice were allowed 14 weeks for hematologic and immunologic reconstitution. Shown in Figure 3 are the proportions of Ly5.1(WT) and Ly5.2(WASP—) cells in various lineages following reconstitution and influenza virus inoculation. Enrichment in the lymphoid lineages was evident and was somewhat greater than the cohorts shown in Figure 1 particularly at the lowest (10%) fraction of input Ly5.1(WT) bone marrow cells. This difference may have been due to the greater genetic homogeneity of the fourth to fifth generation backcross donors, although an effect of the influenza virus inoculation cannot be excluded.

Animals that received 35% or more WT cells exhibited normal percentages (Figure 3B) and absolute numbers (data not shown) of splenic NP-specific CD8+ T cells following reconstitution, whereas the cohort receiving only 10% WT cells were deficient with respect to NP-specific T cells (Figure 3B). Similar trends were observed with respect to cytokine production by NP-stimulated T cells (Figure 3C). Shown in each case are the means, based on the actual data, for each of the individual cohorts along with the predicted means and their estimated standard errors based on the best quadratic fit of the data from the entire group of 21 animals. The results suggest that there is a threshold between 10% and 35% with respect to the minimum number of WT cells required to correct this defect in T-cell immunity in the studied time frame with respect to reconstitution following transplantation.

Oncoretroviral vector–mediated WASP expression

An MSCV-based, bicistronic vector containing the murine WASP coding sequence was constructed (Figure 4A). WASP expression was evaluated by transducing primary murine bone marrow cells via coculture with a GP+E86-derived23 producer cell population. The bone marrow cells were then analyzed for expression of WASP by Western blot analysis and expression of GFP by flow cytometry (data not shown). WASP was readily detectable in primary bone marrow cells from WASP— animals transduced with the MWG vector (data not shown).

Bone marrow cells obtained from either WT or WASP— mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated WASP— recipients. In a series of 4 experiments we generated 18 gene-corrected animals and appropriate control cohorts, the latter consisting of WASP— animals that received transplants of WASP— (18 animals) or WT (14 animals) marrow cells transduced with the control MG vector. Transduction efficiencies of myeloid progenitors within the populations of injected cells ranged from 54% to 88% for the various experiments. The averages for each of the cohorts were as follows: WT/MG = 72%, WASP—/MG = 65%, and WASP—/MWG = 73%. Functional studies were performed between 14 and 24 weeks after transplantation as specified for individual experiments described in this paragraph. The percentage of GFP+ lymphocytes varied from 17% to 98% (mean 60% and median 64%) in the 18 gene-corrected animals. Fourteen of these animals were used in studies of T-cell function; the percentage of GFP+ T cells are given for animals used in each experiment. Of the 4 remaining gene-corrected animals, 2 died and 2 were used for other studies to be reported separately. WASP was demonstrable by Western blot analysis in extracts of peripheral blood leukocytes in animals that had higher percentages of GFP+ lymphocytes and it was not readily detected in some animals that had lower percentages of GFP+ lymphocytes (Figure 4A). No evidence of vector rearrangement was detected on Southern blot analysis from peripheral blood DNA from 5 animals studied, including 2 that lacked detectable WASP on Western blot analysis. Integration position effects may have also influenced the ability to detect WASP, as the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of GFP was variable ranging from 12 to 80 (arbitrary units) in the lymphocyte population. Since both GFP and WASP are expressed from a bicistronic transcript (Figure 4A), we infer that WASP is produced in cells expressing the GFP marker even in animals in which the levels of the protein are insufficient to allow detection on Western blot analysis.

The mild lymphopenia characteristic of murine WAS was corrected in animals that had higher proportions of gene-corrected T lymphocytes (Figure 4B). In contrast, there was no apparent correlation between the percentage of GFP+ T lymphocytes and total lymphocyte count in WAS animals that received WASP— cells transduced with the control MG vector (Figure 4C) or in the group of control animals that received WT cells transduced with the control MG vector (Figure 4D). Thrombocytopenia is mild in murine WAS and variable with different experimental protocols. Although we initially observed a trend toward correction in animals having higher percentages of GFP+ cells, the results ultimately were not statistically significant as data from additional animals were included in the analysis.

Shown in Figure 5 are the percentages of GFP+ cells in various hematopoietic lineages in the 3 cohorts of animals: control animals that received bone marrow cells transduced with the control MG vector, WASP— animals that received WASP— cells transduced with the control MG vector, and WASP— mice that received WASP— cells transduced with the MWG vector. As noted earlier, the average proportion of GFP+, progenitor-derived colonies in the transduced bone marrow did not differ among the groups: WT/MG = 72%, WASP—/MG = 65%, and WASP—/MWG = 73%. Comparison of the WASP—/MWG cohort to the WASP—/MG cohort shows significant enrichment of the former for GFP+ T cells (P < .002), B cells (P < .003), platelets (P < .04), and neutrophils (P < .05). These results are consistent with the relative enrichment in various hematopoietic lineages observed in the competitive repopulation assay (Figures 1 and 3).

Vector-mediated WASP expression corrects the T-cell proliferative and cytokine secretory defects in WASP— mice following reconstitution with transduced stem cells

In 2 separate experiments, 2 gene-corrected WASP— animals that exhibited WASP on Western analysis of peripheral blood leukocytes were killed (total of 4 gene-corrected animals) and splenic T cells were partially purified. In each experiment, 4 control animals were killed: a WT animal, a WASP— animal, a WASP— animal that had received a transplant of WASP— marrow cells, and a WASP— animal that had received a transplant of WT marrow cells. The studies were performed at 23 weeks (Figure 6A) or 30 weeks (Figure 6B) after transplantation. The mitogenic response of splenic T cells to anti-CD3 of the gene-corrected animals was 6-fold to 10-fold higher than that observed with cells from control WASP— animals and was approximately equivalent to the mitogenic response observed with WT cells (Figure 6).

For the same animals, cytokine production in response to stimulation with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody was assayed by flow cytometry following permeabilization and binding of anticytokine antibodies. In addition to TNFα and IFN-γ, we also examined IL-2 synthesis because this cytokine has been previously studied in the context of WAS.9,31 Representative data from assays of these cytokines are shown in Figure 7A-B. The results for the 4 gene-corrected, WASP— animals compared with the positive and negative controls are summarized in Figure 8. Production of each of the cytokines tested was improved in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells derived from the group of gene-corrected animals compared with WASP— animals with the differences reaching statistical significance (P < .03) for IFN-γ (21.3% ± 5.5% standard error [SE] versus 6.3% ± 0.9% SE) and IL-2 (6.5% ± 1.9% SE versus 1.8% ± 0.2% SE) in CD8 cells and for IFN-γ (4.3% ± 1.4% SE versus 1.1% ± 0.3% SE) in CD4 cells. The percentage of GFP+ T cells in the peripheral blood of these animals ranged from 42% to 91% (Figure 6), perhaps accounting for the lower percentage of cytokinepositive cells in the samples from the gene-corrected animals compared with those from the positive controls.

Cytokine secretion by splenic T cells from gene-corrected WASP— mice in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation. Splenic T cells from the same animals used in Figure 6B were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (500 ng/well) in the presence of Brefeldin A and then analyzed by flow cytometry for IFN-γ and TNF-α accumulation as described in “Materials and methods.” MG is the control vector encoding GFP only and MWG is the bicistronic vector encoding WASP and GFP. (A) The percentage of cells per quadrant is shown. Top right: mouse no. 5 (Figure 6B); bottom right: mouse no. 6 (Figure 6B). (B) Representative studies of IL-2 and IFN-γ expression in the same T-cell preparations. The WASP—/MWG preparation is from mouse no. 6 (Figure 6B).

Cytokine secretion by splenic T cells from gene-corrected WASP— mice in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation. Splenic T cells from the same animals used in Figure 6B were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (500 ng/well) in the presence of Brefeldin A and then analyzed by flow cytometry for IFN-γ and TNF-α accumulation as described in “Materials and methods.” MG is the control vector encoding GFP only and MWG is the bicistronic vector encoding WASP and GFP. (A) The percentage of cells per quadrant is shown. Top right: mouse no. 5 (Figure 6B); bottom right: mouse no. 6 (Figure 6B). (B) Representative studies of IL-2 and IFN-γ expression in the same T-cell preparations. The WASP—/MWG preparation is from mouse no. 6 (Figure 6B).

Vector-mediated WASP expression corrects the defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus infection

To test whether gene correction improves the deficient secondary T-cell response to influenza, 10 gene-corrected animals were given primary and secondary challenges with influenza virus, as described in “Defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus infection in WASP— mice is corrected by WT cells,” 20 to 31 weeks after transplantation. Control animals included agematched WASP— or WT mice that did not undergo transplantation, and WASP— mice that received transplants of MSCV-GFP (MG)–transduced WASP— bone marrow cells (negative controls) and MG-transduced WT bone marrow cells (positive controls). The mean percentages of GFP+ T cells for the animals in these 3 cohorts measured 6 to 8 weeks before primary inoculation were 38% (WT/MG, n = 8), 21% (WASP—/MG, n = 8), and 61% (WASP—/MWG, n = 10), reflecting the trend shown in Figure 5. One mouse in each control cohort died and 2 mice in the gene-corrected cohort died prior to secondary inoculation. One mouse in the gene-corrected cohort was not studied after it was humanely killed due to a technical error. The 7 surviving gene-corrected animals were analyzed in 2 groups with controls on 2 successive days; data from 3 animals were lost because of a reagent failure on the second day. The fraction of CD8+ T cells specific for influenza NP antigen was significantly improved in the group of 4 animals studied compared with the negative controls (P < .02) with a mean value comparable to that of the positive controls (Figure 9A). At the time they were killed, these gene-corrected animals had 37%, 76%, 79%, and 90% GFP+ T cells in blood. We also determined whether gene-corrected, NP-specific T cells from the 7 available animals produced cytokines normally after in vitro stimulation with NP antigen (Figure 9B). The means and standard errors for the relevant comparison of cells positive for TNF-α and IFN-γ are as follows: WT/MG versus WASP—/MG = 2.0 ± 0.64 versus 0.23 ± 0.07 (P < .004) and WASP—/MG versus WASP—/MWG = 0.23 ± 0.07 versus 1.78 ± 0.78 (P < .04). The percentage of GFP+ T cells for these 7 animals ranged from 18% to 82% (average, 65%) when last determined in blood prior to the secondary influenza inoculation. Five of 7 animals studied had values of cytokine double-positive cells that were above the mean of the negative control group; one of the 2 animals whose double-positive cells fell below the mean had only 18% GFP+ T cells. These data document improvement of this defect in T-cell function in most gene-corrected animals in response to a specific challenge with influenza virus with the average for all animals indicating a statistically significant impact of vector-mediated WASP expression on T-cell function (Figure 9C).

Discussion

Competitive repopulation studies suggest a repopulating advantage for WT T and B lymphocytes over WASP— cells in WASP— recipients that received transplants of defined mixtures of WT and WASP— bone marrow cells. WASP— animals have a functional immunodeficiency in the form of a reduced secondary T-cell response to influenza, which was corrected in animals that received 35% or more WT cells. Transduction of WASP— hematopoietic repopulating cells with an oncoretroviral vector encoding WASP followed by transplantation of lethally irradiated WASP recipients resulted in variable expression of WASP in leukocytes at levels that, for some animals, approached those of WT controls. Correction of the lymphopenia characteristic of murine WAS was observed in proportion to the fraction of GFP+ T cells in the gene-corrected animals. Splenic T cells exhibited correction of the WASP— proliferative defect and improvement of the cytokine production defects in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 4 of 4 animals studied. The defective secondary T-cell response to influenza virus inoculation was also improved on average, as judged by the fraction of NP-specific CD8+ splenic T cells as well as by the cytokine secretory response of T cells to NP stimulation. Thus, gene correction resulted in improvement in the combination of T-cell and antigen-presenting cell function across a wide range of differentiation stages, which constitutes a stringent test of the feasibility of correcting the immunodeficiency characteristic of WAS by gene transfer. The threshold with respect to WASP-expressing cells for achieving phenotypic correction suggested by the competitive repopulation studies was generally achieved by stem cell–targeted gene transfer, although improvements in vector design will be necessary to insure that adequate levels of WASP are consistently achieved.

Our results complement and extend the recently published studies of Klein and coworkers,32 which describe rescue of T-cell signaling and amelioration of colitis upon transplantation of transduced WAS hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Because of the severity of colitis in the original WASP— strain, the studies of Klein et al were performed in RAG—/—, mice, whereas our experiments were performed in hemizygous WASP— males on the C57Bl/J6 background. Correction of the defect in mitogenesis upon antibody-mediated T-cell receptor stimulation in vitro was documented in both studies. We have extended these observations by demonstrating that gene correction also improves in vitro T-cell cytokine secretion and the defective secondary T-cell response of WASP— mice to influenza virus.

Enhanced repopulation of WT versus WASP— cells in lymphoid tissues of WT recipients has been documented in a competitive repopulation assay.32 We also observed progressive enrichment of genetically modified T- and B-lymphoid cells and, in addition, observed an initial enrichment in neutrophils and monocytes which was nonprogressive during the period of observation. Our results suggest that the enrichment in WASP-expressing cells is of functional relevance in that we found correction of a specificdeficit in immune function with infusion of 35% or more WT cells. A longer period of immune recovery after transplantation and prior to influenza virus challenge might have permitted correction of the immune deficit with a lower proportion of repopulating cells, given the progressive enrichment in T cells observed during the course of our studies (Figures 1 and 3).

Several prior lines of evidence suggest that WASP-expressing hematopoietic cells have a competitive advantage. For example, heterozygous female human carriers of WASP deficiency exhibit preferential accumulation of WASP-expressing cells in multiple lineages.33-35 In an experimental murine transplantation model that utilized heterozygous female repopulating cells, nonrandom inactivation of the X chromosome was found and attributed to a defect in migration of WASP— hematopoietic stem cells.36 The documentation of spontaneous revertants in the WASP gene mutation in a number of patients37-39 is consistent with a selective advantage for WASP-expressing cells in the context of hematopoiesis composed of WASP— cells. Our results showed a progressive enhancement of lymphocyte repopulation by WT or gene-corrected cells, consistent with the critical role of the immunologic synapse in both T cells11 and B cells.40,41 A less-marked, nonprogressive enrichment of WT myeloid cells was also seen. Unexplained is the apparent lack of enrichment in the red cell lineage, which may suggest that enrichment in all gene-expressing cells is occurring at the post–stem cell level in the murine model.

T-cell function in the immune response is critically dependent on antigen-specific T-cell–receptor activation, which results in cell proliferation and cytokine secretion. Stimulation of T cells with anti-CD3 provides a surrogate assay for these critical aspects of T-cell function. The mitogenic response to T-cell receptor stimulation, which is defective in both murine and human WAS, was dramatically corrected by vector-mediated expression of WASP (Figure 6). Improvement in T-cell cytokine production was also documented (Figures 7 and 8). Corrective effects of engineered WASP expression have also been observed in B-cell lines,42,43 macrophages,8 and dendritic cells,44 supporting the notion that a general correction of immune dysfunction in WAS can be achieved by stem cell–targeted gene transfer.

Influenza virus is not among the infectious agents that have been cited as commonly affecting patients with WAS, although pneumonia is a frequent complication.3 However, there are no published surveys of large numbers of patients with WAS whose diagnosis has been confirmed by molecular methods. In studies listing more specific pathogens, pneumococcus is a frequent cause of infectious complications in patients with WAS.45-47 Because the synergy between influenza virus infection and secondary infection by any of a number of other organisms including pneumococcus is well known clinically48 and has been documented in a mouse model,49 a role for influenza virus in clinical complications of WAS cannot be excluded and, in light of our data in the murine model, may deserve closer scrutiny. Vector-mediated WASP expression corrected the defects in influenza-specific T-cell immunity in our studies. As noted above, a recently published study32 has also shown that stem cell–targeted WASP gene transfer results in amelioration of the colitis observed in another WASP— strain.12

The recent development of a lymphoproliferative syndrome in 2 children with common γ-chain deficiency who had been treated 3 years earlier by retroviral-mediated gene transfer has heightened concerns regarding the safety of gene therapy approaches.50,51 Vector-mediated insertional activation of the LMO2 gene, a known proto-oncogene,52 has been demonstrated in the proliferative cells of both patients. Although the oncogenic potential of insertional mutations was recognized previously, the risk was thought to be very low.53 Vector-mediated enforced expression of the common γ-chain gene as another component of the oncogenic mechanism in this patient is at least theoretically possible. An aggressive T-cell lymphoma of thymic origin (CD3+, CD4+, CD8+) was observed in 6 of 90 long-term transplantation survivors in our studies (T.S.S. and A.W.N., unpublished observations, June 2002). Two mice had received cells transduced with the control vector (MG) and 2 mice received cells transduced with the MWG vector. However, the lymphoma cells in these animals did not express GFP, suggesting that the tumors were derived from nontransduced cells, making insertional mutagenesis as an oncogenic mechanism unlikely. Moreover, the other 2 mice had received WT cells after coculture with 3T3 cells and in one of these animals the tumor was documented by Southern blot analysis to be derived from recipient WASP— cells. We conclude that in the context of lethal irradiation and stem cell transplantation, WASP— mice have an enhanced risk for lymphoma development. Even in this context, however, enforced expression of WASP did not appear to increase the risk.

In summary, our studies and those of others32 support the development of gene therapy approaches for WAS. Our data suggest that the current vector design was associated with significant variability in the level of gene expression, which could compromise the potential benefit of stem cell–targeted gene therapy. Future efforts will focus on optimizing WASP gene expression by including an RNA processing element in the vector genome that facilitates nuclear-to-cytoplasmic mRNA transport.54 The β interferon scaffold attachment region has also been shown to enhance vector-mediated gene expression in hematopoietic cells.55 Lentiviral vectors are being explored both to increase the efficiency of gene transfer56 and to facilitate the evaluation of tissue-specific transcriptional elements57 such as the WASP gene promoters58,59 in an effort to more accurately reproduce the normal pattern of WASP expression within the hematopoietic lineages. Features of vector design that enhance safety such as the use of deleted long-terminal repeats (LTRs)56 and the incorporation of insulator elements60 to potentially reduce the risk of insertional activation of a proto-oncogene are also very important considerations.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 10, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3489.

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Program project grant P01 HL 53749, Cancer Center Support CORE grant P30 CA 21765, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant RO1 AI29579, the Hartwell Center for Bioinformatics and Biotechnology at St Jude Children's Research Hospital, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We wish to thank Jean Johnson for her help in the preparation of the manuscript, Xiuling Li for her excellent technical assistance, and Xin Tong for her help with the statistical analyses.

![Figure 6. Proliferation of splenic T cells from gene-corrected, WASP— animals in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation. As described in the text, 2 separate experiments were performed with 2 WASP— animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the MWG vector along with appropriate controls. Splenic T cells were cultured for 48 hours in 96-well dishes coated with anti-CD3 antibody (5 ng/well, overnight, 4°C [panel A]; 50 ng/well, 6 hours, 4°C [panel B]) or in untreated wells (control). 3H-thymidine was added, and 24 hours later total incorporation was measured. Each result is the mean of 3 independent measurements. The cells transplanted into the irradiated WASP— mice and vectors, if any, used for transduction are as follows: lane 1, WASP—; lane 2, WASP— and MG; lane 3, WT; lane 4, WT and mock (A) or WT and MG (B); lanes 5 and 6, 2 separate mice with WASP— cells transduced with the bicistronic MWG vector. The percentage of GFP+ T cells was measured in peripheral blood prior to the proliferation assays. Error bar equals standard error.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/102/9/10.1182_blood-2002-11-3489/6/m_h82135151006.jpeg?Expires=1765930705&Signature=RBhmZm0js4CEJ2OLPgTsu5dmbgjvLlRVwpMzF6VRePPrOH4WtfCr~Wjpf0G~Kd8c8df2OaoYJbYfZ3KAGcjIHkisz-vjPgMfews-582utSRT6lTxxLniD4zCSIg4Dd9nsy40duzKSyuoYrYAcLIiVTiIqxW-8HUmvZgZYukTJB89jexSRvjjL2dSEz2vP71vgjX8trKvPwdArM1~qKnB1a37K-OH7zzspb2jV~M2BPp~j~H8EcRGJqABtM-78cmOOqOT5FQ9THO02h9LssNU0A1NBHfPwJDGHr-C2KLRTD57edgHqFSYxilJYtzvx-WPWjasvMBxZBM5jFQwlG-Xiw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Proliferation of splenic T cells from gene-corrected, WASP— animals in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation. As described in the text, 2 separate experiments were performed with 2 WASP— animals that received transplants of WASP— cells transduced with the MWG vector along with appropriate controls. Splenic T cells were cultured for 48 hours in 96-well dishes coated with anti-CD3 antibody (5 ng/well, overnight, 4°C [panel A]; 50 ng/well, 6 hours, 4°C [panel B]) or in untreated wells (control). 3H-thymidine was added, and 24 hours later total incorporation was measured. Each result is the mean of 3 independent measurements. The cells transplanted into the irradiated WASP— mice and vectors, if any, used for transduction are as follows: lane 1, WASP—; lane 2, WASP— and MG; lane 3, WT; lane 4, WT and mock (A) or WT and MG (B); lanes 5 and 6, 2 separate mice with WASP— cells transduced with the bicistronic MWG vector. The percentage of GFP+ T cells was measured in peripheral blood prior to the proliferation assays. Error bar equals standard error.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/102/9/10.1182_blood-2002-11-3489/6/m_h82135151006.jpeg?Expires=1766344485&Signature=jHoQb1FBJrkv3mes6p72a0dH67D5JmiFh3-prsoy3Rvax9oWk3NyVK4aMg2kDJ0pXgEVEBBjTAYx8WjxS9dKaTuPNVRs8qbF~8hxxXwIzQYRsEyc4UzXGkYR4UCZqORZ~f-TpjbRKT8dW8QkpCBMHRkpxdVhh~k5TXrRXYpOUby1jC7uW14i~4LgYqXu6Kevl6zD9sAOVzaN-nioa3A-peHim6RALSvlwy2WaQIvJHxYVLZDkH6XrLck~V4Isy3LQttcVsokgqPNMRZQRsTvgSWd3tdGOlUlEs8XWITpq9lnNH3iEv8r6zIfJCIxoSfIArDBiOm-a2x4j9YxltyRgw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)