Abstract

The activation of murine dendritic cells by Toxoplasma gondii has recently been shown to depend on a parasite protein that signals through the chemokine receptor CCR5. Here we demonstrate that this molecule, cyclophilin-18 (C-18), is an inhibitor of HIV-1 cell fusion and infection with cell-free virus. T gondii C-18 efficiently blocked syncytium formation between human T cells and effector cells expressing R5 but not X4 envelopes. Neither human nor Plasmodium falciparum cyclophilins possess such inhibitory activity. Importantly, C-18 protected peripheral blood leukocytes from infection with multiple HIV-1 R5 primary isolates from several clades. C-18 bound directly to human CCR5, and this interaction was partially competed by the β-chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 1β (MIP-1β) and by HIV-1 R5 gp120. In contrast to several other antagonists of HIV coreceptor function, C-18 mediated inhibition did not induce β-chemokines or cause CCR5 downmodulation, suggesting direct blocking of envelope binding to the receptor. These data support the further development of C-18 derivatives as HIV-1 inhibitors for preventing HIV-1 transmission and for postexposure prophylaxis.

Introduction

The chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 are the predominant coreceptors for HIV-1 in vivo, and all HIV-1 strains are currently classified as R5, X4, or R5X4.1 As members of the 7 transmembrane–domain G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, CCR5 and CXCR4 share common structural features, including an extracellular N-terminus, 3 extracellular domains, 3 intracellular domains, and an intracytoplasmic C-terminal tail. The functions of CCR5 and CXCR4 as chemokine receptors and as HIV-1 coreceptors are separable, in that the binding sites for their biologic ligands (ie, chemokines) and for HIV-1 gp120 were found to be discrete with some overlap.2-5 Thus, binding of a given protein or small molecule to the HIV-1 coreceptor is not necessarily predictive of HIV-1 inhibition.

Previously, we reported that a soluble tachyzoite extract of the protozoa Toxoplasma gondii (STAg) uses the chemokine receptor CCR5 on murine dendritic cells to induce interleukin-12 (IL-12) production.6 The active component in STAg that signals through CCR5 was recently identified as cyclophilin-18 (C-18).7

In the current study we report that binding of T gondii cyclophilin-18 to human cells expressing CCR5 blocks HIV-1 envelope–mediated fusion and protects peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) from infection with multiple R5 primary HIV-1 isolates. We provide proof-of-concept for further development of C-18 as an inhibitor of HIV-1 transmission and discuss the possibility that T gondii infection in HIV-1–seropositive individuals may provide a selective pressure for viral evolution.

Materials and methods

Starting parasite preparations

Reagents and cell lines

Recombinant C-18 protein was expressed in Escherichia coli and was purified as described previously.7 Polyclonal anti–C-18 (1492) and control (1499) antibodies were prepared as described previously.7

Human cyclophilin and cyclosporin A (CsA) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum cyclophilin (PfCyp19), expressed in E coli and purified as previously described,9 was generously provided by Alan Fairlamb (Wellcome Trust Biocentre, Dundee, United Kingdom). Regulated on activation of normal T cells expressed and secreted (RANTES), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and MIP-1β were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Antibodies against MIP-1α and MIP-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). CCR5.EGFP and M7-CCR5.EGFP were stably transduced into CEM cells by retroviral vector infection using retroviral vector stocks produced by transfecting 293T cells as previously described.10 The CEM.NKR-CCR5 cell line was obtained from John Moore (Cornell University Medical School, NY). The PM1 cell line (a CD4+CXCR4+CCR5+ derivative of the Hut 78 cell line) was previously described.11

CCR5 binding assay

Recombinant C-18 was trace labeled with 125I by Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (San Carlos, CA). CEM (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; no. CCL-119, CXCR4+CCR5–) and CEM.NKR.CCR5 (CXCR4+CCR5+)12 cells were incubated in triplicate with increasing concentrations of 125I-labeled C-18 or human MIP-1β for 90 minutes at 4°C, and the unbound fraction was sampled following centrifugation. The bound fraction was then measured and the dissociation constant for ligand binding calculated using a Graph Pad Prism software program (Mackiev, Cupertino, CA). To assess the specificity of binding, CEM.NKR.CCR5 cells were incubated with 10-μM 125I-labeled recombinant C-18 in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled C-18, human MIP-1β, human cyclophilin A, PfCyp19, or R5 envelope (Ba-L), or X4 envelope (MN) (from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagents Program, Rockville, MD) for 90 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed and the bound fraction measured radioactively.

Recombinant vaccinia viruses and fusion inhibition assay

Recombinant vaccinia viruses vCB28 (JR-FL envelope), vCB43 (Ba-L envelope), and vCB39 (ADA envelope) were kindly provided by Christopher Broder13 (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD). Syncytium formation was measured at different times after coculture (1:1 ratio, 1 × 105 cells each, in triplicate) of target cells (expressing CD4 and coreceptors) and effector cells (CD4–12E1 cells14 infected overnight with 10 pfu/cell of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing HIV-1 envelopes). For measurement of X4 Env-mediated fusion, we used the human lymphoid cell line TF228.1.16, which stably expresses HIV-1 IIIB/BH10 envelope.15 Serially diluted inhibitors were added to the target cells for 60 minutes at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator (3 wells per group). Effector cells were added, and syncytium formation was followed for 3 to 4 hours. Linear regression curves were generated and used to calculate the 50% inhibitory dose (ID50).

HIV-1 viral neutralization

HIV-1 LAI (X4 strain) was kindly provided by Keith Peden (CBER, FDA, Bethesda, MD). The R5 viruses BaL and JR-CSF as well as a panel of primary isolates were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (McKesson BioServices, Rockville, MD). Viral stocks were produced and titered in phytohemagglutinin (PHA)–activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). For viral neutralization by STAg or C-18, serially diluted inhibitors (or human cyclophilin control) were added to target cells in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well, 5 replicates per group). For infection, we used either PM1 cells or human PBMCs activated with PHA-P (0.25 μg/mL, from Sigma) plus hIL-2 (20 U/mL, from R&D) for 3 days. Cells were plated in 96-well plates and inhibitors were added (5 replicates per dilution). After one hour of incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator, virus was added (100 tissue culture infectious dose [TCID50]/well). After 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, unbound virus and inhibitors were washed away, and the plates were cultured for 2 weeks. Supernatants were removed every second day, and the cultures were supplemented with fresh medium. Viral production was determined by measuring p24 in culture supernatants using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (NEN Life Sciences Products, Boston, MA). p24 production was measured every second day for 2 weeks, and the ID50 values were based on results obtained near peak virus production (usually between days 7-11). Viral neutralization is expressed as 50% inhibitory dose (ID50) calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench as described by Shibata et al.16

Receptor internalization assay

PM1 cells (or CEM.NKR.CCR5 cells) were incubated with either a mixture of RANTES and MIP-1β (1 μg/mL each, from Peprotech) or with C-18 (10 μg/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C with occasional shaking. The cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline buffer containing 0.01% azide and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated 2D7 (anti-CCR5; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or FITC-conjugated Leu 3a (anti-hCD4; Becton Dickinson, San Francisco, CA), or FITC-isotype control in the cold and were analyzed by flow cytometry using the FL-1 (FITC channel) on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Lincoln Park, NJ). Delta mean fluorescence channel (Δ MFC) values were calculated by subtracting the mean fluorescent channel (MFC) value of the isotype control from specific antibody staining.

Preparation of human macrophages

Elutriated monocytes (MOs) were obtained from the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health. For the generation of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), 1.5 × 106 monocytes were cultured in 6-well plates in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 1000 units/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Immunex, Seattle, WA) and 10% pooled heat-inactivated human serum. After 5 to 6 days, floating cells were removed and adherent cells were harvested by scraping them from the surface of the wells with a rubber policeman. MDMs were 100% CD3–, more than 85% CD14+, and more than 95% HLA-DR+ as previously described.17,18

Results

STAg from T gondii inhibits R5 HIV-1 cell fusion

We recently demonstrated that STAg is a potent inducer of IL-12 in mouse dendritic cells, and this activity is mediated in part by signaling via the chemokine receptor CCR5.6,7 It was of interest to determine if STAg also acts via human CCR5 and whether the extract inhibits its function as an HIV-1 coreceptor. Using an HIV-1 envelope–dependent cell-fusion assay, we found that STAg blocked the fusion of R5 envelope–expressing 12E1 cells with PM1 target cells (CD4+, CXCR4+, CCR5+). The 50% inhibitory dose (ID50) ranged between 4.4 and 7.0 μg/mL for cells expressing BaL, ADA, and JR-FL envelopes (Table 1). In contrast, no inhibition of fusion was seen between PM1 and the X4 envelope–expressing TF228 target cells (Table 1).

T gondii cyclophilin 18 is responsible for the STAg-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 fusion and infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

We have recently shown that the major component in STAg responsible for its CCR5-dependent IL-12–inducing activity in murine dendritic cells (DCs) is an 18-kDa protein identified as cyclophilin 18 (C-18). The C-18 gene was cloned and expressed in E coli, and the recombinant protein was purified by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography. It was tested in various immunologic assays and used to generate antibodies in rabbits.7

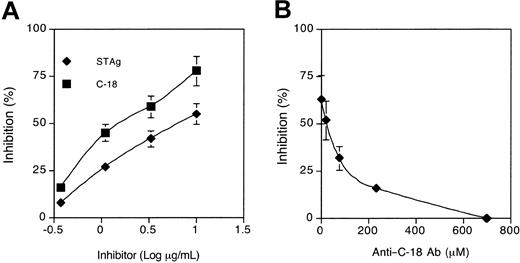

Blocking of HIV-1 fusion by C-18 was found to be either similar or superior to that of STAg, even though it constitutes on average only 1.7% of the total protein in the extract7 (Figure 1A). To determine if C-18 accounts for all the STAg-associated inhibitory activity, polyclonal anti–C-18 rabbit antibodies in increasing concentrations were incubated with STAg (at 10 μg/mL) prior to the fusion assay. As demonstrated in Figure 1B, anti–C-18 antibodies reversed the STAg-mediated HIV-1 fusion inhibition in a dose-dependent fashion, demonstrating that C-18 is the major protein in the parasite extract with this activity. In contrast with the fusion-inhibitory activity of T gondii C-18, neither human-derived nor Plasmodium falciparum–derived cyclophilins had any blocking activity on HIV-1 envelope–mediated cell fusion (Table 2).

C-18 is the principal fusion-inhibiting component in STAg. (A) Inhibition of HIV-1 envelope–mediated cell fusion with STAg and Cyclophilin (C-18) from T gondii. PM1 cells were incubated with serial dilutions of STAg and C-18 for one hour at 37°C and then mixed (1:1, in triplicates) with 12E1 cells infected overnight with recombinant vaccinia (vCB28) expressing JR-FL envelope. Syncytia were scored between 3 and 4 hours of incubation. Calculated ID50 values were as follows: STAg, 7 μg/mL; C-18, 2 μg/mL. Data represent 4 different experiments. No inhibition was observed with recombinant human cyclophilin or with P falciparum cyclophilin (data not shown). (B) Antibodies to C-18 inhibit STAg-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 fusion. PM1 cells were incubated with STAg (10 μg/mL) in the presence of increasing concentrations of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) fraction from rabbit antiserum raised against recombinant C-18 (1499). 12E1 cells expressing R5 envelope (JR-FL) were added after one hour at 37°C, and syncytia were scored after 3 to 4 hours. Control cultures (no inhibitor added) contained between 400 to 500 syncytia per well. IgG from a control antiserum prepared against an irrelevant peptide (1492) did not block STAg-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 fusion (not shown). The data are representative of 3 experiments performed. Error bars represent SD of the means of 3 replicates per data point.

C-18 is the principal fusion-inhibiting component in STAg. (A) Inhibition of HIV-1 envelope–mediated cell fusion with STAg and Cyclophilin (C-18) from T gondii. PM1 cells were incubated with serial dilutions of STAg and C-18 for one hour at 37°C and then mixed (1:1, in triplicates) with 12E1 cells infected overnight with recombinant vaccinia (vCB28) expressing JR-FL envelope. Syncytia were scored between 3 and 4 hours of incubation. Calculated ID50 values were as follows: STAg, 7 μg/mL; C-18, 2 μg/mL. Data represent 4 different experiments. No inhibition was observed with recombinant human cyclophilin or with P falciparum cyclophilin (data not shown). (B) Antibodies to C-18 inhibit STAg-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 fusion. PM1 cells were incubated with STAg (10 μg/mL) in the presence of increasing concentrations of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) fraction from rabbit antiserum raised against recombinant C-18 (1499). 12E1 cells expressing R5 envelope (JR-FL) were added after one hour at 37°C, and syncytia were scored after 3 to 4 hours. Control cultures (no inhibitor added) contained between 400 to 500 syncytia per well. IgG from a control antiserum prepared against an irrelevant peptide (1492) did not block STAg-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 fusion (not shown). The data are representative of 3 experiments performed. Error bars represent SD of the means of 3 replicates per data point.

T gondii cyclophilin inhibits infection of PBMCs with primary HIV-1 R5 viruses

Further development of C-18 as a coreceptor inhibitor depends on its ability to block infection with cell-free virus. It is important to establish the breadth and efficiency of this activity using multiple primary HIV-1 strains. A panel of either laboratory-adapted or primary clade B and clade C isolates from different global regions were used. As can be seen in Table 3, significant inhibition was observed with all R5 isolates with ID50 values ranging between 0.4 and 14 μg/mL. These values are similar to those reported for several HIV-1 neutralizing mAbs.19,20 Again, no inhibition of primary X4 isolates was observed, and human cyclophilin did not inhibit HIV-1 infection (Table 3 and data not shown).

Cyclosporin A inhibits C-18–mediated blocking of CCR5 coreceptor function

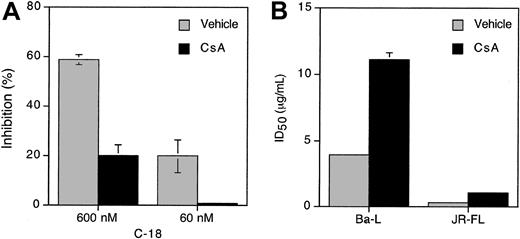

Cyclosporin A (CsA) is a major ligand for cyclophilins and a competitive inhibitor of their peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity.21,22 To investigate whether CsA binding to C-18 affects its ability to inhibit HIV-1 fusion, we preincubated serially diluted C-18 with CsA (50 μg/mL) for 60 minutes at 37°C. C-18 alone or the C-18/CsA mixtures were added to PM1 target cells for 60 minutes at 37°C, followed by addition of effector cells expressing JR-FL (R5) envelope. Syncytia were scored between 3 and 4 hours. In the presence of CsA, the fusion-inhibiting activity of C-18 was greatly diminished (Figure 2A). Similarly, CsA preincubation reduced C-18–mediated inhibition of HIV-1 infection in PBMCs, increasing the ID50 values for BaL and JR-FL by 3-fold (Figure 2B).

Cyclosporin A, antagonist of C-18, interferes with its CCR5 fusion-blocking activity. (A) Cyclosporin A (CsA) reduces C-18 blocking of HIV-1 R5-env cell fusion. Serial 3-fold dilutions of C-18 (from 10 to 0.36 μg/mL) were preincubated with CsA (50 μg/mL) for one hour at 37°C and were then added to PM1 cells for an additional one hour at 37°C. The untreated or treated PM1 cells were mixed with effector cells expressing either JR-FL Env (shown) or Ba-L Env (not shown). Syncytia were scored between 3 and 4 hours. Calculated ID50 is as follows: C-18, 4.2 μg/mL; C-18 + CsA, 130 μg/mL. The experiment shown is representative of 3 experiments performed. (B) Preincubation of C-18 with Cyclosporin A (CsA) significantly reduces its ability to inhibit HIV-1 infection. C-18 (serial dilutions) was incubated with CsA (50 μg/mL) for one hour at 37°C before adding to PM1 cells for one hour at 37°C. Virus was then added at 100 TCID50/well (5 replicates per group) and incubated with cells for 2 days before extensive washings. The ID50 values were calculated according to Reed and Muench. Data shown are for day 11 (Ba-L) or day 21 (JR-FL). CsA alone at the same concentration had no inhibitory or stimulatory effects on HIV infection in any of the assays. Error bars represent SD of the means of 3 replicates per data point.

Cyclosporin A, antagonist of C-18, interferes with its CCR5 fusion-blocking activity. (A) Cyclosporin A (CsA) reduces C-18 blocking of HIV-1 R5-env cell fusion. Serial 3-fold dilutions of C-18 (from 10 to 0.36 μg/mL) were preincubated with CsA (50 μg/mL) for one hour at 37°C and were then added to PM1 cells for an additional one hour at 37°C. The untreated or treated PM1 cells were mixed with effector cells expressing either JR-FL Env (shown) or Ba-L Env (not shown). Syncytia were scored between 3 and 4 hours. Calculated ID50 is as follows: C-18, 4.2 μg/mL; C-18 + CsA, 130 μg/mL. The experiment shown is representative of 3 experiments performed. (B) Preincubation of C-18 with Cyclosporin A (CsA) significantly reduces its ability to inhibit HIV-1 infection. C-18 (serial dilutions) was incubated with CsA (50 μg/mL) for one hour at 37°C before adding to PM1 cells for one hour at 37°C. Virus was then added at 100 TCID50/well (5 replicates per group) and incubated with cells for 2 days before extensive washings. The ID50 values were calculated according to Reed and Muench. Data shown are for day 11 (Ba-L) or day 21 (JR-FL). CsA alone at the same concentration had no inhibitory or stimulatory effects on HIV infection in any of the assays. Error bars represent SD of the means of 3 replicates per data point.

STAg and C-18–mediated inhibition of HIV-1 fusion does not depend on β-chemokine production

For some HIV-1 inhibitors, an indirect mechanism was found mediated by induction of β-chemokine production in peripheral blood leukocytes.23 Several β-chemokines bind to CCR5 and induce its internalization. Thus, it was important to differentiate between direct and indirect mechanisms for the inhibition of HIV-1 fusion mediated by C-18. To address this question, either STAg or C-18 was added to the fusion assay in the presence of antibodies against MIP-1α and MIP-1β. The addition of neutralizing anti-chemokine antibodies had no effect on the fusion-inhibitory activity of either STAg or C-18 (Table 4). The same antibodies could effectively block the inhibitory activity of a mixture of MIP-1α and MIP-1β β-chemokines (Table 4). Identical results were obtained with anti-RANTES antibodies (not shown).

C-18 does not induce CCR5 downmodulation

Several classes of inhibitors targeting the HIV coreceptors have been described. In addition to blocking relevant sites, chemokine analogs have been shown to induce rapid downmodulation of chemokine receptors and/or prevent their recycling to the surface.10,24-26 In contrast, small molecule inhibitors probably exert their effect primarily through receptor occupancy and/or by inducing conformational changes.27-29 We therefore tested the possibility that C-18 induces downmodulation of CCR5. In 2 cell lines (PM1 and CEM.NKR-CCR5), no decrease of either CCR5 or CD4 expression was found after incubation of cells with C-18 at 37°C for 2 to 3 hours (Table 5) or for 18 hours (data not shown). In the same experiments, a combination of RANTES and MIP-1β did induce downmodulation of CCR5 (Table 5).

To further address this point, we compared fusion inhibition of stably transfected CEM cells expressing either wild-type (WT) CCR5 or M7-CCR5 genes. The M7-CCR5 construct was generated by polymerase chain reaction mutagenesis and contains 7 mutations in the cytoplasmic tail at Ser336/Ser337/Tyr339/Thr340/Ser342/Thr343/Ser349, rendering it internalization deficient.10 C-18 blocked fusion of both WT and M7-CCR5 transfectants, and the ID50 values for the M7-CCR5–expressing cells were similar to or lower than those for the WT CCR5-expressing cells (Table 6). Together these data demonstrate that CCR5 internalization is not required for C-18–mediated HIV-1 fusion inhibition.

C-18 binds directly to CCR5

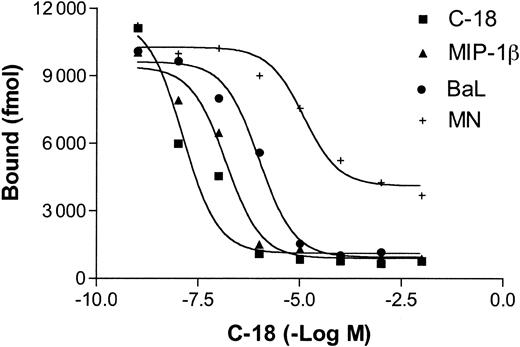

Iodinated C-18 was previously shown to bind to a human cell line stably transfected with CCR5 (CEM.NKR-CCR5). The dissociation constant of C-18 was calculated to be 3.646 nM compared with 0.559 nM for MIP-1β, suggesting a modest affinity. Importantly, the binding of C-18 to hCCR5-expressing cells was completely blocked by unlabeled C-18, but not by P falciparum cyclophilin, and was partially blocked by MIP-1β.7 Here we demonstrate that the binding of radiolabeled C-18 to CEM.NKR-CCR5 cells is also partially blocked by soluble R5 gp120 (from Ba-L). Inhibition with X4 env (MN) was at least 10-fold less efficient and the small activity observed may be attributed to very low avidity binding to CCR5 due to common elements shared by CCR5 and CXCR430 (Figure 3). Thus, it seems likely that the primary mechanism responsible for the inhibition of HIV-1 cell fusion mediated by T gondii C-18 is a steric inhibition of the interaction between gp120 and the CCR5 coreceptor, as has been previously demonstrated for several small molecule inhibitors.10,31 This inhibitory mechanism differs from that of β-chemokine analogs, most of which act primarily by inducing receptor internalization (in addition to partial blocking of env-binding).

Binding of C-18 to CCR5 is partially blocked by MIP-1β and R5 (BaL) envelope. CEM.NKR-CCR5 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of unlabeled C-18, human MIP-1β, R5 (Ba-L) Env, or X4 (MN) Env prior to addition of a fixed concentration of 125I-C-18. After incubation for 90 minutes at 4°C, the bound counts were measured as described in “Materials and methods.”

Binding of C-18 to CCR5 is partially blocked by MIP-1β and R5 (BaL) envelope. CEM.NKR-CCR5 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of unlabeled C-18, human MIP-1β, R5 (Ba-L) Env, or X4 (MN) Env prior to addition of a fixed concentration of 125I-C-18. After incubation for 90 minutes at 4°C, the bound counts were measured as described in “Materials and methods.”

C-18 blocks fusion of macrophages with R5 envelope–expressing cells

β-Chemokines more effectively inhibit entry of HIV-1 into CD4+ T cells than into macrophages or adherent cell lines cotransfected with huCD4 and coreceptor genes. While in some studies RANTES was observed to inhibit HIV infection of macrophages, prolonged presence of the inhibitor was required, suggesting the possible involvement of post–entry-inhibitory mechanisms.32 This difference was correlated with the observation that β-chemokines and their derivatives induce CCR5 internalization and interfere with receptor recycling in T cells, but much less so in macrophages or adherent cells.33-35 It was important, therefore, to determine if C-18 inhibits HIV fusion in macrophages with a similar efficiency as it does in T cells. Indeed, in 2 independent experiments, it was found that C-18 inhibited macrophage fusion with cells expressing R5 envelope with ID50 values not significantly different from the ID50 obtained with the T-cell line PM1 (Table 6). In the same experiments, inhibition by RANTES or MIP-β ranged between 20% and 30% at a concentration (100 ng/mL) previously shown to fully block HIV-1 infection in T cells (data not shown). Previously, we demonstrated that a combination of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES at this concentration incompletely blocked R5 fusion in macrophages, and this blocking was not dependent on G-protein signaling.36 Thus, compared with β chemokines, C-18 fusion-blocking activity in macrophages is similar to its activity in T cells. These findings support the further development of C-18 as a broad inhibitor of R5 HIV-1 viruses that is likely to be active against infection of diverse types of primary target cells.

Discussion

Molecular mimicry of chemokine ligands has been described for several pathogens and includes both structural homologs of known chemokines as well as structural mimicry without common sequences.37 It was recently found that T gondii cyclophilin-18 constitutes a component of the IL-12–inducing activity of the parasite. C-18 was shown to activate murine dendritic cells via the chemokine receptor CCR5.

Unlike human CCR5, murine CCR5 is not functional as an HIV-1 coreceptor. However C-18 binds to CCR5 of both species, which share a high degree of homology. C-18 binds to human CCR5 with modest affinity compared with the biologic ligand MIP-1β. Nevertheless, this binding was sufficient to block HIV-1 env-mediated cell fusion and infection of cell lines and PBMCs with cell-free virus including primary isolates.

The structural requirements for C-18–mediated CCR5 binding are under investigation. Other cyclophilins do not bind to CCR5 (ie, human cyclophilin and PfCyp19), implying that the peptidylprolyl isomerase enzymatic activity of C-189 is either not required or not sufficient for its CCR5-binding activity. However, cyclosporin A, an antagonist of cyclophilin, significantly reduced the HIV-1 inhibiting activity of C-18 (and also its IL-12–inducing activity in murine dendritic cells). This finding does not necessarily imply direct involvement of the cyclophilin active site in CCR5 binding. Rather it may reflect locking of C-18 in a conformational state less favorable for CCR5 binding.21,22

Previously described inhibitors that target the HIV-1 coreceptors were shown to act by a plethora of mechanisms, inducing receptor internalization, interfering with receptor recycling, direct blocking of env-binding, or through some form of steric hindrance or conformational changes in the coreceptors.10,25,33,38 C-18 did not induce CCR5 downmodulation, either in the absence or presence of anti–C-18 antibodies. This finding was surprising since C-18 signals through human CCR5, as determined by Ca++ mobilization and chemotaxis.7 However, signaling is not always coupled with internalization. Internalization of GPCRs often requires phosphorylation of specific residues in the cytoplasmic tail and recruitment of intracellular adaptor molecules such as β-arrestin, which facilitates internalization.39,40 Phorbol ester treatment induces rapid internalization of CXCR4 but not CCR5, even though both receptors undergo phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tail.41 The absence of a di-leucin motif in CCR5 may explain the inability of phorbol esters (or C-18) to induce CCR5 internalization.42 Alternatively, C-18 may induce protein kinase C–mediated phosphorylation of CCR5, followed by a rapid dephosphrylation, previously described as a mechanism to maintain cell-membrane receptors in a nonphosphorylated, signaling-competent status.43

In our laboratory (and others), chemokine-mediated inhibition of macrophage fusion with R5 viruses is inefficient, requiring high concentrations of β-chemokines, and does not involve receptor internalization.10,33,36 In contrast, C-18 blocked HIV fusion of both T cells and macrophages with similar efficiencies. This finding further distinguishes C-18 from β-chemokines (or their derivatives) and places it in the class of inhibitors that do not require receptor downmodulation for efficient blocking of viral entry. A similar mechanism has been proposed for the small molecule R5 antagonist TAK 779,27 the X4 antagonist AMD3100,44,45 and small peptide-mimetops of RANTES.38 Thus, C-18 represents a new type of microbial-derived product that may be developed as HIV-1 cell-entry inhibitor.

In the HIV-1 infectivity assays, the ID50 values obtained with primary HIV-1 isolates from clades B and C ranged between 0.4 and 14 μg/mL. Such values can be used as a proof-of-concept to support further development of C-18 as an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. The lack of CCR5 downmodulation will mean minimal perturbation to the normal function of CCR5-bearing cells.

It is interesting that, while C-18 binds to both murine and human CCR5, only the human chemokine receptor can support HIV-1 infection. This observation predicts that the critical contact residues on CCR5 for C-18 and HIV gp120 binding are not identical. However, some overlap must exist in order for C-18 to function as an inhibitor of HIV-1 cell entry. Indeed, R5 gp120 (Ba-L) partially inhibited the binding of iodinated C-18 to CCR5-expressing CEM cells, while X4 gp120 (MN) behaved as a much weaker competitor. Preliminary data suggest that C-18 also binds to rhesus CCR5 and blocks simian immunodeficiency virus infection. This finding raises the possibility of testing C-18 (or its derivatives) in vivo in a nonhuman primate model of HIV infection.

It is interesting to speculate what role may be played by T gondii cyclophilin 18 during natural HIV-1 infection. T gondii is endemic in many parts of the world, and many HIV-1–infected individuals have serum antibody titers against the parasite. It is not clear how much cyclophilin is produced during acute or latent T gondii infection in vivo and whether it reaches high enough levels in the blood and interstitial fluids to influence HIV-1 replication. While its binding to CCR5 is not as avid as is MIP-1β, it nevertheless could provide a local shield against the spread of CCR5-tropic viruses and thus apply selection advantage for virus variants with expanded coreceptor tropism (ie, R5X4), thereby contributing to viral diversification in individuals infected with both pathogens simultaneously. The latter hypothesis could be examined by quantitating viral subtypes in the T gondii+/HIV+ subpopulation.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 10, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1096.

Supported in part by the Universitywide AIDS Research Program Institutional Support Award no. IS02-SI-704.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Phil Murphy, Carol Weiss, Keith Peden, and Marina Zaitseva for critical review of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Alan Fairlamb for providing the Pf cyclophilin and to Jose Ribeiro for his advice and support of this project.