Abstract

Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, formerly STI571) is an effective therapy for all stages of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). While responses in chronic-phase CML are generally durable, resistance develops in many patients with advanced disease. We evaluated novel antileukemic agents for their potential to overcome resistance in various imatinib-resistant cell lines. Using cell proliferation assays, we investigated whether different mechanisms of resistance to imatinib would alter the efficacy of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) or 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (decitabine) alone and in combination with imatinib. Our results indicate that resistance to imatinib induced by Bcr-Abl overexpression or by engineered expression of clinically relevant Bcr-Abl mutants does not induce cross-resistance to As2O3 or decitabine. Combined treatment with these agents and imatinib is beneficial in cell lines that have residual sensitivity to imatinib monotherapy, with synergistic growth inhibition achieved only at doses of imatinib that overcome resistance. In some imatinib-resistant cell lines, combination treatments that use low doses of imatinib lead to antagonism. Apoptosis studies suggest that this can be explained in part by the reduced proapoptotic activity of imatinib in resistant cell lines. These data underline the importance of resistance testing and provide a rational approach for dose-adjusted administration of imatinib when combined with other agents.

Introduction

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder characterized by the (9;22) chromosomal translocation that produces a shortened chromosome 22, the so-called Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome.1 During the stable, or chronic, phase of the disease, leukemic myeloid progenitors undergo excess proliferation with retained capacity for differentiation. After 4 to 6 years, the disease inevitably transforms into a fatal acute leukemia, referred to as blast crisis.2 Multiple lines of evidence have established that the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, the product of the Ph chromosome, is central to the pathogenesis of CML.3 Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, STI571), an orally administered selective inhibitor of the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, has significant activity in all stages of the disease.4,5 Nearly all patients in first chronic-phase CML achieve complete hematologic remissions, and in 40% to 70% of these patients, the Ph chromosome is no longer detected using standard cytogenetic assays.6,7 However, the durability of these responses is still under investigation, and patients in more advanced phases of CML frequently develop resistance to imatinib monotherapy.8,9

Clinically detected mechanisms of resistance include amplification of Bcr-Abl at the genomic or transcript level and mutations in the Abl kinase domain.10-12 Nineteen different mutated residues have been reported,13 with mutations of Y253, E255, T315, and M351 accounting for approximately 60% of mutations detected in patients at the time of relapse. Some mutants, such as M351T or Y253F, retain high or intermediate sensitivity to imatinib, suggesting that dose escalation may recapture a response. Others, such as T315I and E255K, are insensitive to imatinib at clinically achievable doses and will require alternative therapeutic strategies.10,11,14,15

The current studies were designed to assess the potential of novel antileukemic agents, arsenic trioxide (As2O3) and 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (decitabine), to cooperate with imatinib in combating resistance induced by Bcr-Abl mutation or gene amplification. As2O3 was selected based on favorable in vitro data previously reported.16-19 Given the capability of As2O3 to down-regulate Bcr-Abl protein levels by translational modulation,20 it was of particular interest to determine whether the same would be true in cell lines that overexpress Bcr-Abl or express Bcr-Abl mutations. Decitabine, a hypomethylating agent, was selected because of its combined cytotoxic and chromatin-modifying activity and its efficacy in CML blast crisis patients.21,22

Our studies reveal that combinations of imatinib with these antileukemic drugs demonstrate additive to synergistic activity against resistant cell lines that retain residual sensitivity to imatinib. In contrast, combined treatment of highly resistant p210T315I-positive cell lines showed no additional effects over monotherapy. We also show that As2O3 is capable of down-regulating Bcr-Abl protein levels in resistant lines with induced overexpression of wild-type Bcr-Abl or engineered expression of the Bcr-Abl mutant T315I. This decrease in Bcr-Abl expression may allow sufficient reductions in Bcr-Abl kinase activity by imatinib to lead to the observed additive to synergistic antiproliferative activity.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and drug preparation

MO7e, a human megakaryoblastic cell line,23 was grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 20% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), 2% (vol/vol) l-glutamine (Gibco), 1% (vol/vol) penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep), and 10 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Immunex, Seattle, WA).

32D, a murine myeloid hematopoietic cell line,24 was grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 2% l-glutamine, 1% pen/strep, and 15% WEHI-conditioned media as the source of interleukin-3.

All other cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 2% l-glutamine, and 1% pen/strep. “Imatinib-naive” cells used were the human Bcr-Abl–positive cell line K562,25 as well as MO7e and 32D cells engineered to express p210Bcr-Abl (MO7p210, 32Dp210).26,27

Imatinib-resistant Ba/F3p210 mutant lines Ba/F3p210Y253F, Ba/F3p210T315I, and Ba/F3p210M351T were generated as previously reported28 and cultured under the same conditions as the Bcr-Abl–positive cell lines mentioned above.

Imatinib resistance was induced in cell lines that were initially imatinib-sensitive (Bcr-Abl–expressing human AR230-s and murine Baf/BCR-ABL-s) by continuous culture in the presence of gradually increasing doses of imatinib up to 1 μM.29 The resulting AR230-r1 and Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 cells show unaffected viability in the continuous presence of 1 μM imatinib due to overexpression of Bcr-Abl. Genetic analysis of both resistant lines revealed BCR-ABL gene amplification as the underlying mechanism of Bcr-Abl protein induction.29 These cells were maintained in media containing 1 μM imatinib.

Imatinib, kindly provided by E. Buchdunger (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), was prepared as a 10 mM stock solution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and kept at –20°C. Arsenic trioxide (As2O3; Trisenox; Cell Therapeutics, Seattle, WA) was purchased through the pharmacy at Oregon Health and Science University. The stock solution (1 mg/mL, approximately 5 mM) was stored at room temperature. 5-Aza-2-deoxycytidine (decitabine; Sigma A3656) was prepared at 10 mM in PBS, and stocks were kept at –80°C. Serial dilutions of all drug stocks were performed in RPMI 1640 on the day of use.

Proliferation assay (MTT assay)

The methyl-thiazol-tetrazolium (MTT) assay was performed as described previously.30 Cells were plated in triplicate or quadruplicate at 5 × 103 cells per well and exposed to escalating doses of each drug independently or in combination. MTT uptake was assayed daily to ensure exponential growth of the untreated cells. Means and standard deviations generated from 3 to 4 independent experiments are reported as the percentage of growth versus control at 72 hours. Data were analyzed by the median-effect method (Calcusyn software; Biosoft, Ferguson, MO) to calculate the doses with 50% inhibition of proliferation (Dm or IC50 values). This algorithm calculates the Dm value by linearizing dose-response curves. To ensure a valid statistical analysis, only experimental data for which the linear correlation coefficient of the median-effect plot was more than 0.9 were included.31 Where this was not applicable, the IC50 value was derived manually from the dose-response curve generated by Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Combination studies were designed according to Chou and Talalay31 : Cell lines were incubated with increasing doses of drug dilutions or combinations of drug dilutions. Calcusyn software was used to calculate the combination index (CI) at different levels of growth inhibition as a quantitative measure of the degree of drug interaction. This algorithm is based on the isobologram method and was chosen because of its ability to calculate combined activity at a wide range of growth inhibition. Combined drugs were used at fixed molar ratios to accommodate software requirements. Equitoxic drug doses that produced approximately 50% of growth inhibition in single-agent experiments were chosen to determine an appropriate fixed molar ratio of 2 combined drugs (Table 1).

Because imatinib-resistant AR230-r1 and Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 cells are maintained in 1 μM imatinib, no meaningful inhibition can be achieved at doses below 1 μM imatinib (Figure 1). Thus, data obtained at low imatinib doses were not analyzable by Calcusyn. CI simulations, therefore, were performed by setting 1 μM imatinib as the baseline dose (control).

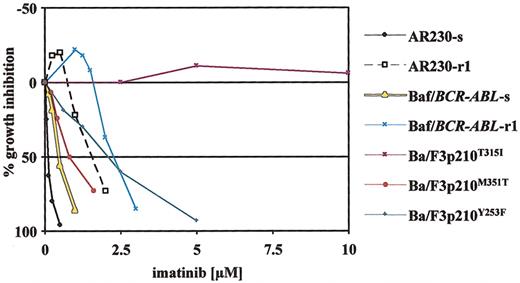

Dose-response curves obtained by MTT assays for various imatinib-sensitive and -resistant cell lines after 3 days of continuous exposure to imatinib. In vitro resistance to imatinib in cell lines is either conferred by Bcr-Abl overexpression (AR230-r1, Baf/BCR-ABL-r1)29 or engineered expression of Bcr-Abl with various point mutations in Ba/F3p210 cells (Ba/F3p210Y253F/M351T/T315I).28 The different resistant lines represent graded levels of resistance to imatinib with low (Ba/F3p210M351T), intermediate (AR230-r1, Baf/BCR-ABL-r1, Ba/F3p210Y253F), and complete (Ba/F3p210T315I) resistance as compared with sensitive counterparts (AR230-s, Baf/BCR-ABL-s). Plotted is the percentage of growth inhibition (y-axis) through exposure to imatinib at increasing doses (x-axis). Single data points are mean values of at least 3 independent experiments.

Dose-response curves obtained by MTT assays for various imatinib-sensitive and -resistant cell lines after 3 days of continuous exposure to imatinib. In vitro resistance to imatinib in cell lines is either conferred by Bcr-Abl overexpression (AR230-r1, Baf/BCR-ABL-r1)29 or engineered expression of Bcr-Abl with various point mutations in Ba/F3p210 cells (Ba/F3p210Y253F/M351T/T315I).28 The different resistant lines represent graded levels of resistance to imatinib with low (Ba/F3p210M351T), intermediate (AR230-r1, Baf/BCR-ABL-r1, Ba/F3p210Y253F), and complete (Ba/F3p210T315I) resistance as compared with sensitive counterparts (AR230-s, Baf/BCR-ABL-s). Plotted is the percentage of growth inhibition (y-axis) through exposure to imatinib at increasing doses (x-axis). Single data points are mean values of at least 3 independent experiments.

Mean CI values from at least 3 independent experiments were subjected to a 1-sided t test to identify synergism (CI value significantly lower than 1), additivity (CI value not significantly different from 1), or antagonism (CI value significantly more than 1). Further classification of various levels of synergy was adapted from the Calcusyn users manual (Table 2).32

Activated caspase-3 assay

Staining for activated caspase-3 was performed using the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated polyclonal rabbit antiactive caspase-3 antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (PharMingen), and Perm/Wash Buffer (PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were analyzed within 1 hour after staining. Acquisition and analysis were performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using CellQuest software. A minimum of 10 000 cells per sample were analyzed.

Immunoblotting

Cell lines were incubated in the presence of different concentrations of As2O3 or in media alone, as a control. After 24 and 48 hours, cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and cells were harvested; 1 × 107 cells per milliliter were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM orthovanadate, and 10 μg/mL aprotinin. A total of 100 μg protein was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Abl antibody (8E9, kindly provided by Jean Y. J. Wang, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA) or antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10.33 Equal protein loading was demonstrated by blotting for actin with the antiactin antibody Ab-1 (Oncogene, Boston, MA). Immunoblots were probed with a secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody (Promega, Madison, WI) and developed by using the enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Autoradiographs were scanned with a LumiImager (BoehringerMannheim, Mannheim, Germany) to quantitate the signal intensity.

Sequencing of the Abl kinase domain

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNAEasy kit. Complementary DNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers. Primers for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification were BCR-F4 (5′-ACAGCATTCCGCTGACCATCAATAAG-3′) and ABL-R6 (5′-AGAACTTGTTGTAGGCCAG-3′). Reaction conditions were as described.34 The PCR products were then subjected to automated sequencing from both directions using primers ABL-F4 (5′-TCCCCCAACTACGACAA-3′) and ABL-R6.

Colony-forming assays

Colony-forming assays in the presence of recombinant human (rh) stem cell factor (50 ng/mL), 10 ng/mL rh GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL rh interleukin-3 (IL-3) with (erythroid burst-forming unit [BFU-E]) or without (granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming unit [CFU-GM]) 3 units per milliliter of rh erythropoietin were performed as described previously.19 All patients were in chronic- or accelerated-phase CML with failure to achieve a major cytogenetic response to imatinib. Approval was obtained from the Oregon Health and Science University institutional review board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ficoll-separated cells (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) were plated at 5 × 104/mL to 1 × 105/mL density. The cells were treated with imatinib and As2O3 or decitabine along a range of concentrations. After a 2-week incubation at 37°C, BFU-Es and CFU-GMs were counted. Only clusters with more than 50 cells were counted as a colony. Assays were done in duplicate. Results were calculated as the percentage of growth versus control.

Results

Analysis of antiproliferative activity in cell lines

MTT assays were performed to determine the antiproliferative effects on various cell lines of the respective drugs or combinations of drugs. In addition to cell lines derived from CML patients (K562, AR230), we screened murine hematopoietic (32D) and human megakaryoblastic cell lines (MO7e) with and without extrinsic expression of p210Bcr-Abl (32Dp210, MO7p210) to assess for Bcr-Abl–specific activity. Furthermore, we studied resistant cell lines caused by either Bcr-Abl overexpression (AR230-r1 and Baf/BCR-ABL-r1) or by expression of mutated Bcr-Abl (Ba/F3p210T315I, Ba/F3p210M351T, Ba/F3p210Y253F). These mutants were chosen because they are among the most frequently detected mutations in patient samples with resistance to imatinib. In addition, these mutations represent different levels of resistance to imatinib as shown in Figure 1 (high: T315I; intermediate: Y253F; low: M351T).

As2O3. Experiments that included As2O3 focused primarily on imatinib resistance because efficacy in various CML lines and cell lines with induced expression of Bcr-Abl has already been reported.17-19 Our previously reported data are included in Table 1 for comparison. As shown in Table 1, As2O3 inhibits cell growth in the nanomolar (murine cell lines) to low micromolar (human cell lines) dose range. Cross-resistance to As2O3 was not observed in any of the imatinib-resistant lines. As2O3 had a virtually identical effect on murine Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 cells that overexpress Bcr-Abl as on their sensitive counterpart (Table 1). The Bcr-Abl–overexpressing human cell line AR230-r1 was even 2-fold more sensitive to As2O3 than are AR230-s cells (Dm value = 2.6 ± 0.51 μM in AR230-s versus 0.94 ± 0.13 μM in AR230-r1 cells). Given that plasma concentrations of 1 to 2 μM As2O3 are considered clinically relevant and tolerable,35 this result is of clinical interest. It is also noteworthy that mutated Bcr-Abl does not affect the efficacy of As2O3 in Ba/F3 cells as shown by unchanged Dm values in M351T-, Y253F- and T315I-mutant lines.

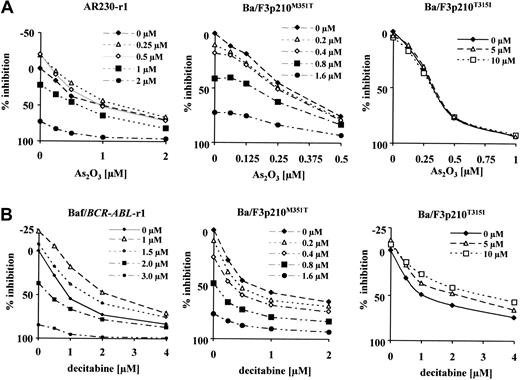

As2O3 with imatinib. Combination drug assays were performed using imatinib-resistant cell lines as well as their sensitive counterparts (AR230-s, Baf/BCR-ABL-s). Proliferation data obtained using AR230-s cells did not qualify for analysis by the median-effect method, because the linear correlation coefficient was less than 0.9 (“Materials and methods”). The same is true for Ba/F3p210T315I, where no inhibition by imatinib alone was observed. Representative dose-response curves for resistant lines are given in Figure 2A. These plots demonstrate that enhanced inhibition of proliferation can only be achieved when imatinib doses reach levels that overcome resistance (shown for AR230-r1 and Ba/F3p210M351T cells). In contrast, in Ba/F3p210T315I cells, where cell growth is not inhibited up to 10 μM imatinib, the combination of imatinib with As2O3 is not better than As2O3 alone.

Growth response of various imatinib-resistant cell lines. Response to the combination of imatinib plus As2O3 (A) or imatinib plus decitabine (B). Fixed dose ratios of either combination were tested in MTT assays. Different curves indicate increasing doses of imatinib with the doses of the second combined drug depicted on the x-axis. Plotted is the percentage of growth inhibition of the untreated control (y-axis).

Growth response of various imatinib-resistant cell lines. Response to the combination of imatinib plus As2O3 (A) or imatinib plus decitabine (B). Fixed dose ratios of either combination were tested in MTT assays. Different curves indicate increasing doses of imatinib with the doses of the second combined drug depicted on the x-axis. Plotted is the percentage of growth inhibition of the untreated control (y-axis).

Results of CI simulations for these data are summarized in Table 2, giving CI values at 50% and 80% growth inhibition. The combination of imatinib and As2O3 achieves more favorable combined activity at higher levels of inhibition in all cell lines studied (Table 2). In Baf/BCR-ABL-s and -r1 cells, we even observed slight to moderate antagonism at the IC50, with conversion to additivity at the IC80. Additive drug interaction at both the IC50 and IC80 is seen in AR230-r1 and Ba/F3p210M351T. Synergy was observed at the IC80 using Ba/F3 cells that express p210Y253F, a mutant with intermediate sensitivity to imatinib.

Decitabine. Despite some early in vitro studies that compared the antileukemic effects of cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) and its derivative decitabine,37,38 systematic preclinical studies exploring the in vitro cytotoxicity of decitabine in Bcr-Abl–positive leukemia cells are lacking. Therefore, we studied the antiproliferative activity of decitabine not only in imatinib-resistant but also in “imatinib-naive” cells. In addition to the human CML cell line K562, we tested cells with engineered Bcr-Abl expression (MO7p210, 32Dp210) to assess Bcr-Abl–specific effects. As shown in Table 1, the susceptibility of various cell lines to the inhibitory activity of decitabine varies widely, with Dm values as low as 0.033 μM (MO7e) and as high as 1.33 μM (K562). Resistance to imatinib due to Bcr-Abl overexpression does not confer cross-resistance to decitabine in AR230-r1 cells or in Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 cells. Moreover, mutations of Bcr-Abl do not affect the antiproliferative activity of decitabine in Ba/F3p210 cells (Table 1).

Imatinib with decitabine. Synergistic activity for the combination of imatinib and decitabine was observed in K562 and MO7p210 cells over a wide dose range (IC50 and IC80) and at the IC80 in Ba/F3p210 cells carrying the mutations Y253F and M351T (Table 2). CI values for Bcr-Abl–overexpressing, imatinib-resistant Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 and AR230-r1 cells were in the range of additive activity, with synergy only for AR230-r1 cells at the IC50 (Table 2). Similar to what has been found for the combination of imatinib and As2O3, enhanced inhibition of proliferation of Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 cells by combined treatment strongly depends on reaching dose levels of imatinib that effectively inhibit cell growth (Figure 2B). Combined treatment at low dose levels of imatinib leads to less growth inhibition as compared with exposure to decitabine only.

As shown in Table 1, the growth response of Ba/F3p210T315I cells to decitabine is not different from their counterparts expressing wild-type Bcr-Abl. However, when combined with 10 μM imatinib, a 4-fold increase of the IC50 for decitabine is observed (Figure 2B). This finding suggests that the presence of imatinib in cells expressing Bcr-Abl mutation T315I induces resistance to decitabine. This demonstrates again that the activity of combinations depends on achieving at least some effect with imatinib alone.

Activation of caspase-3 by combined treatment regimens

We next analyzed the ability of As2O3 and decitabine in conjunction with imatinib to induce activation of caspase-3, an early marker of apoptosis. AR230-r1 cells were continuously exposed to 1 μM or 2 μM imatinib for 48 hours either alone or in combination with 1 μM As2O3 or 0.5 μM decitabine, respectively. Cells were labeled with a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to activated caspase-3. Flow cytometric analysis was then performed to quantify the percentage of cells that are positive for activated caspase-3. Treatment of AR230-r1 cells with 1 μM imatinib did not induce apoptosis above baseline for activated caspase-3 in untreated cells (not shown). Treatment with 1μM As2O3 alone resulted in 8% of cells staining positive for activated caspase-3. Combined treatment (CombTx in Figure 3) with 1 μM imatinib and 1 μM As2O3, however, induced significantly less apoptosis than one would predict from the sum of single-agent treatments (Σ in Figure 3). In contrast, when 1 μMAs2O3 was combined with 2 μM imatinib, significantly more cells were positive for activated caspase-3 than would be predicted from the sum of the single-agent treatments. As illustrated in Figure 3B, combination studies of imatinib with decitabine revealed a similar trend, although the differences were not statistically significant. Thus, in AR230-r1 cells, this combination is additive for inducing apoptosis at both imatinib dose levels.

Activation of caspase-3. Activation in AR230-r1 cells exposed to the combinations of imatinib plus As2O3 (A) and imatinib plus decitabine (B) at resistant (1 μM) and sensitive (2 μM) doses of imatinib. AR230-r1 cells exposed to 1 μM imatinib show low-level activation of caspase-3 (C). Combination treatment with a second agent (CombTx) leads to fewer apoptotic cells than one would predict from the sum of single-agent treatment (Σ) in the presence of 1 μM imatinib (1 μM + 1 μM [A] or 1 μM + 0.5 μM [B]) but to more apoptosis than one would predict from single-agent treatment in the presence of 2 μM imatinib (2 μM + 1 μM [A] or 2 μM + 0.5 μM [B]). Differences were significant for imatinib plus As2O3 as determined by the t test (*P < .05), indicating synergy, whereas they were not significant for imatinib plus decitabine, indicating additivity. Columns represent means of 3 independent experiments ± SD.

Activation of caspase-3. Activation in AR230-r1 cells exposed to the combinations of imatinib plus As2O3 (A) and imatinib plus decitabine (B) at resistant (1 μM) and sensitive (2 μM) doses of imatinib. AR230-r1 cells exposed to 1 μM imatinib show low-level activation of caspase-3 (C). Combination treatment with a second agent (CombTx) leads to fewer apoptotic cells than one would predict from the sum of single-agent treatment (Σ) in the presence of 1 μM imatinib (1 μM + 1 μM [A] or 1 μM + 0.5 μM [B]) but to more apoptosis than one would predict from single-agent treatment in the presence of 2 μM imatinib (2 μM + 1 μM [A] or 2 μM + 0.5 μM [B]). Differences were significant for imatinib plus As2O3 as determined by the t test (*P < .05), indicating synergy, whereas they were not significant for imatinib plus decitabine, indicating additivity. Columns represent means of 3 independent experiments ± SD.

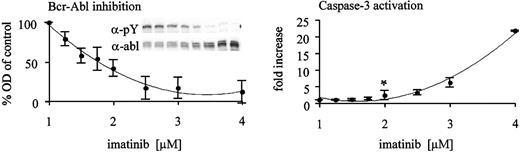

Quantification of kinase inhibition relative to induction of apoptosis

We next asked whether the observed threshold of imatinib required for synergism with As2O3 is related to the degree of Bcr-Abl kinase inhibition that is achieved. Therefore, we exposed the Bcr-Abl–overexpressing cell line Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 to graded concentrations of imatinib for 48 hours and analyzed whole cell lysates for tyrosine-phosphorylated Bcr-Abl as a measure of kinase activity. Cells were also analyzed for activation of caspase-3 by flow cytometry to assess the correlation between kinase inhibition and induction of apoptosis. As illustrated in Figure 4, 50% inhibition of Bcr-Abl kinase activity is the threshold of kinase inhibition required for induction of apoptosis. A concentration of 2 μM imatinib is required to meet this threshold in Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 cells, which mirrors the results obtained by MTT assays (Figure 2).

Induction of apoptosis requires inhibition of the Bcr-Abl kinase to a certain threshold in Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells. Whole cell lysates of Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells were analyzed after 48 hours of exposure to gradually increasing doses of imatinib (x-axis). Western blots using antiphosphotyrosine (α-pY) and antiabl (α-abl) antibodies were performed (insert in left panel). Bcr-Abl kinase activity was derived after densitometry (OD, y-axis) and correction for protein expression (pBcr-Abl/Bcr-Abl ratio). Fractions of the same cultures were analyzed for caspase-3 activation (right panel). Data points represent means of 4 independent experiments ± SD. Statistical analysis using a 1-sided t test revealed 2 μM imatinib as the first dose level with increased apoptosis above baseline (*P < .05).

Induction of apoptosis requires inhibition of the Bcr-Abl kinase to a certain threshold in Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells. Whole cell lysates of Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells were analyzed after 48 hours of exposure to gradually increasing doses of imatinib (x-axis). Western blots using antiphosphotyrosine (α-pY) and antiabl (α-abl) antibodies were performed (insert in left panel). Bcr-Abl kinase activity was derived after densitometry (OD, y-axis) and correction for protein expression (pBcr-Abl/Bcr-Abl ratio). Fractions of the same cultures were analyzed for caspase-3 activation (right panel). Data points represent means of 4 independent experiments ± SD. Statistical analysis using a 1-sided t test revealed 2 μM imatinib as the first dose level with increased apoptosis above baseline (*P < .05).

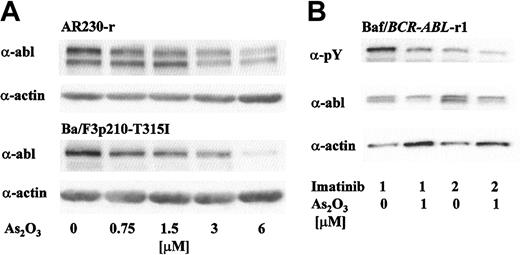

Bcr-Abl protein degradation by As2O3 in imatinib-resistant cell lines

As2O3 has been shown to decrease expression of Bcr-Abl in K562 cells by inducing translational down-regulation at clinically relevant doses.17,20 Bcr-Abl degradation precedes the loss of cell viability and activation of caspase-3.19 This indicates a possible relationship between Bcr-Abl down-regulation and the antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity of As2O3 in Bcr-Abl–positive cells. To investigate the potential of As2O3 to decrease Bcr-Abl expression in imatinib-resistant cell lines, we exposed AR230-r1 and Ba/F3p210T315I cells to gradually increasing doses of As2O3 for 48 hours. Using Western blot analysis with subsequent densitometry, we detected a dose-dependent decrease of Bcr-Abl protein in both cell lines (Figure 5a). Actin expression was stable at doses up to 6 μMAs2O3.

As2O3 induces down-regulation of Bcr-Abl protein in overexpressing (AR230-r1, Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1) and mutant (Ba/F3p210T315I) Bcr-Abl–expressing cells resistant to imatinib. (A) Exponentially growing cells were exposed to increasing doses of As2O3. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and protein expression levels were determined by Western blot analysis using equal amount of protein. Blots were probed with antiabl (top panel) and antiactin antibodies (bottom panel). (B) Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells were exposed to 1 or 2 μM imatinib ± 1 μMAs2O3 for 48 hours. Phosphotyrosine content and protein expression of p210Bcr-Abl were analyzed using α-pY and α-abl antibodies. Protein loading was controlled by probing for actin.

As2O3 induces down-regulation of Bcr-Abl protein in overexpressing (AR230-r1, Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1) and mutant (Ba/F3p210T315I) Bcr-Abl–expressing cells resistant to imatinib. (A) Exponentially growing cells were exposed to increasing doses of As2O3. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and protein expression levels were determined by Western blot analysis using equal amount of protein. Blots were probed with antiabl (top panel) and antiactin antibodies (bottom panel). (B) Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells were exposed to 1 or 2 μM imatinib ± 1 μMAs2O3 for 48 hours. Phosphotyrosine content and protein expression of p210Bcr-Abl were analyzed using α-pY and α-abl antibodies. Protein loading was controlled by probing for actin.

In a separate experiment, Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells were exposed to 1 μM or 2 μM imatinib in the presence of 1 μM As2O3. As depicted in Figure 5B, the amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated Bcr-Abl further decreased when imatinib was combined with As2O3, reflecting the combined effects of kinase inhibition by imatinib and reduced protein expression triggered by As2O3. This implies that cotreatment with As2O3 may reduce the dose threshold of imatinib needed to overcome resistance to apoptosis.

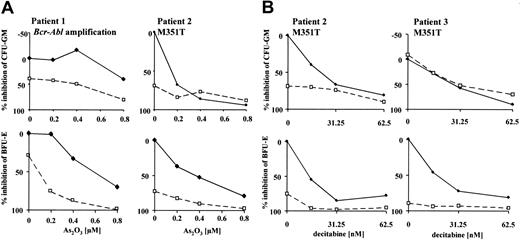

Activity of combined treatment in primary cells

To assess the efficacy of combined treatment in imatinib-resistant primary cells, we evaluated the molecular mechanisms of resistance in patients with available cells for in vitro cultivation. All patients were in late chronic- or accelerated-phase CML and had never achieved a major cytogenetic response with imatinib or had lost this response despite continued therapy with imatinib. At the time of evaluation, patients were on 800 mg (n = 5), 600 mg (n = 1), or 300 mg (n = 1) imatinib daily. Sequence analysis of the Abl kinase domain revealed 2 patients with the p210M351T mutations as the probable mechanism of resistance. Cytogenetic and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis detected 1 patient with BCR-ABL amplification as the most likely cause of resistance to imatinib. No mechanism of resistance could be determined for the remaining patients. Colony-forming assays of mononuclear bone marrow cells in the presence of imatinib and As2O3 or decitabine were performed on patients where sufficient material was available (Figure 6; data of patients with detected mechanisms of resistance are shown). Cells were exposed to 0 μM or 0.5 μM imatinib. Generally, enhanced growth inhibition was seen only in cases where resistance could be overcome by imatinib alone. The effect was more pronounced in erythroid progenitors (BFU-Es), which appear to be inherently more sensitive than CFU-GMs to imatinib alone as well as the combination.

Combined activity of imatinib and As2O3 or decitabine in colony-forming assays of primary CML cells with defined mechanisms of resistance to imatinib. Growth of CFU-GMs and BFU-Es was assessed after continuous exposure to combined treatment for 14 days. Cells were grown in the presence of 0 μM (♦) or 0.5 μM (□) imatinib with increasing doses of the combined agent (x-axis); 0.5 μM was selected because this represents dose escalation under our assay conditions.19 Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib have been determined by cytogenetic and FISH analysis and sequencing of the Abl kinase domain. Results of resistance testing are given next to patient number (M351T or BCR-ABL amplification). Data points represent means of duplicate experiments.

Combined activity of imatinib and As2O3 or decitabine in colony-forming assays of primary CML cells with defined mechanisms of resistance to imatinib. Growth of CFU-GMs and BFU-Es was assessed after continuous exposure to combined treatment for 14 days. Cells were grown in the presence of 0 μM (♦) or 0.5 μM (□) imatinib with increasing doses of the combined agent (x-axis); 0.5 μM was selected because this represents dose escalation under our assay conditions.19 Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib have been determined by cytogenetic and FISH analysis and sequencing of the Abl kinase domain. Results of resistance testing are given next to patient number (M351T or BCR-ABL amplification). Data points represent means of duplicate experiments.

Discussion

This study evaluates 2 novel antileukemic agents, As2O3 and decitabine, as potential candidates to overcome imatinib resistance in patients with CML. The focus of our analysis was imatinib-resistant cell lines that reflect clinically identified mechanisms of resistance to imatinib: Bcr-Abl point mutations and overexpression of Bcr-Abl. In the various cell lines tested, both combinations generally achieved additive to synergistic activity, in particular at high degrees of inhibition (IC80), with the exception of Ba/F3p210T315I cells. These cells are completely resistant even to high doses of imatinib. The combination of imatinib and decitabine appears to be superior to imatinib plus As2O3 when comparing the levels of synergy and the dose range over which synergy can be achieved. The level of synergy for imatinib plus decitabine is in the range of that observed using the combination of imatinib and cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C),39,40 an agent closely related to decitabine. This may reflect the common mechanism of action of these 2 drugs. Because decitabine combines cytotoxic activity with the ability to modulate gene expression by demethylating CpG islands in DNA, the antileukemic activity of this agent might be even more potent.21 However, our studies examined end points of cytotoxicity within 48 hours (apoptosis) or 72 hours (proliferation assays), while most studies examining reexpression of silenced genes by decitabine require 3 to 5 days of exposure to this agent.41 We therefore assumed that effects seen with decitabine are due to short-term cytotoxic effects rather than due to effects on gene expression.

The in vitro studies reported here suggest that the quality of combined effects in imatinib-resistant cells depends to a large degree on administering imatinib at doses that are able to overcome resistance to growth inhibition. Whereas this is feasible in Bcr-Abl–overexpressing cells (Baf/BCR-ABL-r1, AR230-r1) and cells that express Bcr-Abl mutants M351T and Y253F, resistance cannot be overcome in the T315I mutant cells. Thus, combined treatment in resistant patients with mutation T315I may not enhance efficacy. This observation is in line with a report by Hoover et al,42 where the farnesyl-transferase inhibitor SCH66336 was shown to cooperate with imatinib in Baf/BCR-ABL-r1 and AR230-r1 cells but not in Ba/F3p210T315I cells. These data are consistent with the notion that residual activity of imatinib is essential for favorable combined activity with alternative antileukemic drugs.

The caspase-3 assays with the Bcr-Abl–overexpressing AR230-r1 cells indicate that the apoptotic response to As2O3 and, to a lesser extent, decitabine, is modulated by the concentration of imatinib (Figure 3). Thus, imatinib at low concentrations (1 μM) produces less apoptosis than would be expected from the sum of the single agents, while at 2 μM more apoptosis than expected from the sum of the agents is detected. These findings are consistent with data from the proliferation assays. The fact that combination treatment with As2O3 leads to fewer than expected apoptotic cells in the presence of 1 μM imatinib, but more than expected apoptotic cells at 2 μM, implies that increasing the inhibition of the Bcr-Abl kinase to a certain threshold is necessary to achieve synergy. Quantitative assessment of kinase inhibition in conjunction with detection of apoptosis demonstrated that in Baf3/BCR-ABL-r1 cells the threshold for inducing apoptosis with imatinib alone is at 50% kinase inhibition (Figure 5). This is achieved at 2 μM, exactly the dose where enhanced growth inhibition by combined treatment was observed in the proliferation assays (Figure 2B). We therefore conclude that effective combined treatment requires dosages of imatinib that overcome resistance to apoptosis. This suggests that quantitative analysis of kinase inhibition in patients could further improve treatment outcome by adjusting the imatinib dose according to the degree of kinase inhibition.

These findings further support the hypothesis that patients with resistance to imatinib may benefit from adding decitabine or As2O3 only if they harbor a resistance mechanism that is amenable to a simultaneous dose escalation of imatinib. This may be the case in patients with overexpression of wild-type Bcr-Abl or expression of the 253 and 351 mutation but not in patients with the 315 mutation. Clinical trials are underway to determine whether this hypothesis is valid.43

As was demonstrated for imatinib-sensitive cell lines,17,20 As2O3 is also able to reduce cellular Bcr-Abl protein levels in cells that are resistant to imatinib due to Bcr-Abl overexpression or point mutation. This may allow sufficient exposure to imatinib to reduce the kinase activity below the threshold required for the induction of apoptosis. Reductions in Bcr-Abl protein expression have also been reported using geldanamycin and 17-AAG, 2 inhibitors of the heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90).44 These findings suggest the possibility of using As2O3 or 17-AAG to reduce intracellular Bcr-Abl levels, even in cases such as the T315I mutant, where imatinib has no inhibitory effect on the kinase.

The results from primary cell assays indicate that enhanced growth inhibition can be achieved in clinically relevant samples. However, because patient cells represent polyclonal cell populations, conclusions based on distinct mechanisms of resistance must be drawn with caution. Besides mutation or BCR-ABL amplification that has been detected, other yet undetected factors that modulate drug activity (ie, drug efflux45 ) may be present in the same samples.

Recently, 2 groups provided evidence that early quiescent CML progenitor cells show primary resistance to the proapoptotic activity of imatinib in vitro.46,47 Using CD34+-selected CML progenitors, Holtz et al also showed that induction of apoptosis by chemotherapy or As2O3 can be negatively affected by combined treatment with imatinib.48 These data reveal that drug interactions in primary CML cells may also be a function of the developmental stage of the leukemic cells. Thus, for clinical decision making, genotyping of BCR-ABL alone may not reliably predict response and may have to be supplemented by functional tests. These observations warrant close attention in clinical trials of combinations.

In summary, our data emphasize the importance of incorporating resistance testing into clinical decisions and clinical trials, because optimal antileukemic treatment may depend on the resistant genotype. This report also emphasizes the need for reliable quantitative assays to determine the kinase inhibition by imatinib in vivo for optimal dosing in combined regimens.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 21, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1074.

B.J.D. supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and grants from the National Cancer Institute, The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, T. J. Martell Foundation, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. P.L. is a recipient of a postdoctoral grant of the Deutsche Krebshilfe, Dr Mildred Scheel Stiftung, Germany.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are very grateful to all members of our laboratory for helpful discussions and to Sarah Anderson and Chris Koontz for administrative assistance. We also thank Dr Antony Bakke, head of the Oregon Health and Science University Cancer Institute's Flow Cytometry Core, for technical advice.

![Figure 3. Activation of caspase-3. Activation in AR230-r1 cells exposed to the combinations of imatinib plus As2O3 (A) and imatinib plus decitabine (B) at resistant (1 μM) and sensitive (2 μM) doses of imatinib. AR230-r1 cells exposed to 1 μM imatinib show low-level activation of caspase-3 (C). Combination treatment with a second agent (CombTx) leads to fewer apoptotic cells than one would predict from the sum of single-agent treatment (Σ) in the presence of 1 μM imatinib (1 μM + 1 μM [A] or 1 μM + 0.5 μM [B]) but to more apoptosis than one would predict from single-agent treatment in the presence of 2 μM imatinib (2 μM + 1 μM [A] or 2 μM + 0.5 μM [B]). Differences were significant for imatinib plus As2O3 as determined by the t test (*P < .05), indicating synergy, whereas they were not significant for imatinib plus decitabine, indicating additivity. Columns represent means of 3 independent experiments ± SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/1/10.1182_blood-2003-04-1074/6/m_h80145417003.jpeg?Expires=1766352430&Signature=YUxtrM12G5vhirHQ3LoDbBUfhqI32Vtnyr-vllC1~mCEefl2NUsEEYYrSTwooNoAuelHRF8iCN8oHEGTpcfo13J5z0P3pKHHQ7ZbMzZ6BgCsM4w9jxdexoVh-RWPYqmOq01eW1RDWpkogS1ZosKsFZ4y9q7YJOm2F2IU0wKfAAppXiczEqEInrfAluR7mBT3J6uMbBvUaC40ZNLPHN7wZJ4pRSJugi8kwzbSd-yh1hsAgdhi81ZSA758w4L7kd3AjID--LrT~V4~OFjmIMQBkQYSQtFhGX5BrIodQdnAZVDuhmLeveoCRM9BSNHL1qiSvdRfIM~sDM8VRksctI1H9A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)