Abstract

Etoposide is a substrate for P-glycoprotein, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and UGT1A1. Glucocorticoids modulate CYP3A and P-glycoprotein in preclinical models, but their effect on clinical etoposide disposition is unknown. We studied the pharmacokinetics of etoposide and its catechol metabolite in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, along with polymorphisms in CYP3A4, CYP3A5, MDR1, GSTP1, UGT1A1, and VDR. Plasma pharmacokinetics were assessed at day 29, after 1 month of prednisone (n = 102), and at week 54, without prednisone (n = 44). On day 29, etoposide clearance was higher (47.4 versus 29.2 mL/min/m2, P < .0001) than at week 54. The day 29 etoposide or catechol area under the curve (AUC) was correlated with neutropenia (P = .027 and P = .0008, respectively). The relationship between genotype and etoposide disposition differed by race and by prednisone use. The MDR1 exon 26 CC genotype predicted higher day 29 etoposide clearance (P = .002) for all patients, and the CYP3A5 AA and GSTP1 AA genotypes predicted lower clearance in blacks (P = .02 and .03, respectively). The UGT1A1 6/6, VDR intron 8 GG, and VDR Fok 1 CC genotypes predicted higher week 54 clearance in blacks (P = .039, .036, and .052, respectively). The UGT1A1 6/6 genotype predicted lower catechol AUC. Prednisone strongly induces etoposide clearance, genetic polymorphisms may predict the constitutive and induced clearance of etoposide, and the relationship between genotype and phenotype differs by race.

Introduction

Etoposide is a commonly used anticancer agent with a broad range of antitumor activity.1 It is often combined with other agents, such as cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, glucocorticoids, or anthracyclines, but little is known about its drug interactions. Interactions that affect the pharmacokinetics of etoposide disposition may influence its efficacy or toxicity because the relationship between the pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamic action of etoposide has been well documented.2-4

A number of host- and treatment-related factors may influence etoposide disposition. Etoposide is a substrate for P-glycoprotein (Pgp, the MDR1 gene product),5 whose expression in tissues such as biliary tract, intestine, and renal tubules suggests that it has a role in the absorption and excretion of xenobiotics such as glucocorticoids6 and etoposide.5 Etoposide is O-demethylated by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and CYP3A5,7 whose expression is regulated partly by the vitamin D receptor (VDR).8,9 The most stable O-demethylated metabolite of etoposide, its catechol, provides an index of reactive metabolites, which bind to DNA and cellular proteins and exert intrinsic cytotoxic effects,10-12 many of which are attenuated by glutathione conjugation.13 Although the glutathione transferase (GST) that conjugates etoposide metabolites is not known, GSTs exhibit overlapping substrate specificity, and GSTP1 has been linked to cancer outcome in several prior studies and undergoes a common polymorphism.14,15 Etoposide is also glucuronidated by UGT1A1.16

Glucocorticoids induce and inhibit CYP3A17 and Pgp18,19 in preclinical models. Their clinical effect on etoposide disposition has not been documented. Many anticancer drugs, including etoposide, are substrates for both CYP3A and Pgp.20 Because it is difficult to predict, based on preclinical data, whether glucocorticoids are likely to increase or decrease the clearance of CYP3A/Pgp substrates, clinical pharmacokinetic data are needed to address the possible drug interactions in vivo. Moreover, although there are common genetic polymorphisms in genes coding for proteins that may influence etoposide disposition, or may influence any effect of glucocorticoids on etoposide pharmacokinetics, their relationship to etoposide disposition has not heretofore been evaluated. Therefore, we studied the pharmacokinetics of etoposide and its CYP3A-formed catechol metabolite, as well as genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A4, CYP3A5, MDR1, GSTP1, UGT1A1, and VDR, in children undergoing treatment for newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), with and without glucocorticoid pretreatment.

Patients and methods

Patients

Plasma etoposide pharmacokinetics were studied in 109 children with newly diagnosed ALL treated on the St Jude ALL study Total XIIIB between 1994 and 1998. The protocol (summarized in Table 1)21,22 was approved by the St Jude Children's Research Hospital Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from parents, guardians, or patients (as appropriate) according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Pharmacokinetic studies

The first pharmacokinetic study was performed on day 29, after 28 days of remission induction therapy including prednisone 40 mg/m2/d. Data are available from a total of 102 of these patients; 7 were excluded due to confounding drug use. In the subset of 48 patients who had higher-risk ALL and therefore received etoposide during continuation therapy,23 a second pharmacokinetic study was performed at week 54, at least 2 weeks after the last dose of glucocorticoid; 4 of these patients were excluded due to confounding drug use, leaving 44 patients available for evaluation. The duration of any inductive effect of glucocorticoids on clinical pharmacokinetics has not been established, but based on the half-lives of dexamethasone and prednisone, the mechanism of putative induction (increased transcription of the CYP3A or Pgp genes), and the half-lives for turnover of the proteins involved,24 any effect would likely have dissipated by 3 to 7 days following glucocorticoid administration. The in vivo inducibility index was defined as the ratio of the day 29 to the week 54 etoposide clearance in the subset of patients who were evaluable at both time points without confounding drug use (n = 41). An additional pharmacokinetic study was performed at week 19 after reinduction therapy that followed 21 days of prednisone 40 mg/m2/d in a small subset (n = 6). Drug histories for the week prior to and the day of etoposide administration at day 29 and week 54 were prospectively obtained by a research nurse and screened for all possible medications known to interact with CYP3A or Pgp or both. The only likely interacting agents were azole antifungals, anticonvulsants, or unscheduled glucocorticoids; the relevant pharmacokinetic study for such courses was excluded from the analysis.

Etoposide (300 mg/m2) was given intravenously as a 2-hour infusion, and plasma samples were obtained at 4 to 6 time points, 2 to 25 hours after the start of the infusion. Etoposide dose and administration schedules were identical at day 29, week 54, and throughout the treatment protocol. Actual doses and infusion times were recorded prospectively and were used in the analyses. The concentrations of etoposide and its catechol metabolite were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection.25 The pharmacokinetic model was a first-order 2-compartment model with Bayesian estimation of parameters for the parent drug and the catechol metabolite.26,27 The area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) from hour 0 to hour 24 was estimated by using noncompartmental techniques with concentrations simulated at 10-minute intervals.

Pharmacodynamics

The change in absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was defined as the ratio of postetoposide ANC (measured 6 to 8 days after etoposide) to pre-etoposide ANC (determined the morning of the day etoposide was given). The time point of 6 to 8 days was chosen because this was assessed in most patients at both day 29 and week 54 (regardless of toxicity), whereas earlier time points were not, and later time points might have been confounded by other chemotherapy.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from normal blood cells. Genotyping was performed for 8 polymorphic loci using the indicated methods. CYP3A4*1B and CYP3A5*3 were assessed as described.28 The MDR1 exon 21 2677G>T/A,29 MDR1 exon 26 3435C>T,30 VDR intron 8 G>A,31 and GSTP1 313A>G32 polymorphisms were genotyped by single-base extension (SBE) and separated by denaturing HPLC (DHPLC).33 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and extension primers were: MDR1 exon 21 2677G>T/A, 5′-CTGGCTTTGCTACTTTCTG-3′ and 5′-TATCCTTCATCTATGGTTGG-3′ and 5′-TATTTAGTTTGACTCACCTTCCCAG-3′ (extension); MDR1 exon 26 3435C>T, 5′-TAAGGGTGTGATTTGGTTGC-3′ and 5′-AATGTTCAGTGGCTCCGAG-3′ and 5′-CGGGTGGTGTCACAGGAAGAGAT-3′ (extension); VDR intron 8 G>A, 5′-CACAGATAAGGAAATACCTACT-3′ and 5′-CTCATCACCGACATCATGTC-3′ and 5′-GAGCAGAGCCTGAGTATTGGGAATG-3′ (extension); and for GSTP1, 5-AGGGCTCTATGGGAAGGACC-3′ and 5′-GTCAGACCAAGCCACCTGAG-3′ and 5′-TAGTTGGTGTAGATGAGGGAGA-3′ (extension). For the SBE reactions, PCR-amplified products were treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I, incubated in 10 μL volumes with 1 μM extension primer, 250 μM each ddNTP and 1.25 U thermosequenase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), and cycled at 96°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 60°C for 30 seconds for 60 cycles. Separation of the SBE products was performed on a WAVE 3500HT DHPLC system (Transgenomic, Omaha, NE) at 70°C after denaturation of the samples. The VDR Fok 1 start site polymorphism34 was genotyped by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion35 with primers 5′-GACTCTGGCTCTGACCGTGGC-3′ and 5-ACAGATCCGGGGCACGTTC-3′. The UGT1A1 promoter repeat polymorphism was assessed as previously described.36

Statistical analysis

The distribution of race (black, white) and sex in the day 29 and week 54 groups was compared by the χ2 test, and the distribution of age in these groups was compared by t test. The serum albumin concentration, plasma etoposide clearance, and catechol AUC were compared at day 29 versus week 54 using the Wilcoxon matched-pair test. The correlation between age and etoposide clearance, between etoposide AUC and catechol AUC, and between the AUC and change of ANC was estimated by the Spearman rank correlation. For the 8 cases with undetectable ANC after therapy, the ANC was considered to be 4/μL (the midrange value between 0 and the lowest detectable ANC). The distribution of genotypes between the racial groups was tested using the χ2 test with the Yates correction.

A few rare genotypes (eg, MDR1 exon 21 A/G [n = 5 at day 29, n = 3 at week 54] and A/T [n = 2 at day 29, n = 1 at week 54]; UGT1A1 (TA)5/6 [n = 4 at day 29, n = 2 at week 54], (TA)5/7 [n = 2 at day 29, n = 1 at week 54], (TA)6/8 [n = 1 at day 29], and (TA)7/8 [n = 1 at day 29, n = 1at week 54]) were excluded from the genotype/phenotype statistical analyses involving those loci. We tested the relationship between each genotype of interest and the etoposide clearance within each racial group by the Kruskal-Wallis test for the univariate analysis. Genotype/phenotype associations with P ≤ .2 in the univariate analyses were included in multivariate analyses using multiple linear regression models. Genotypes included in the multivariate analyses were treated as ordered categorical variables and tested for trend. For multivariate analyses, we fitted a single model on all the patients, including both black and white patients, with interaction terms between race and each genotype, to detect genotypes whose effects on phenotypes differed between racial groups. Stepwise variable selection based on Akaike information criteria was used to obtain the final set of predictive genotypes in the multivariate analysis. In the final model, we built race-specific contrasts for those factors interacting with race and tested their significance by F test after adjusting for other significant predictors. We applied weighted linear regression analysis for etoposide clearance, with weights being the reciprocal of the variance estimates of the etoposide clearance obtained from the pharmacokinetic model fitting. We used robust linear regression of catechol AUC to accommodate extreme values. We also applied linear mixed effect models that used all the data on both occasions and obtained very similar results as to genotype/phenotype associations (data not shown).

Because the analysis was exploratory, P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patients

We observed no significant difference between the patients evaluable at day 29 (n = 102; 77 whites and 25 blacks) and at week 54 (n = 44; 27 whites and 17 blacks) in age, race distribution (white versus black), sex distribution, or serum albumin concentration (the lowest value obtained on days 27 through 29 and the lowest value obtained during weeks 52 and 53 for each patient; P > .12). The median age for the subgroup evaluable on day 29 is 7.1 years versus 7.3 years for patients evaluable at week 54, with the same range between 0.4 years and 18.7 years.

Pharmacokinetics of etoposide in relation to prednisone treatment

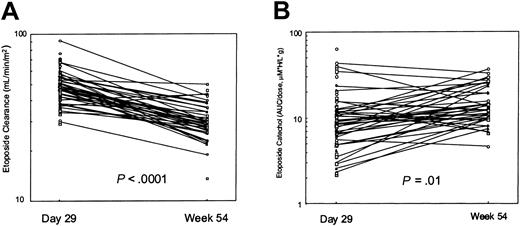

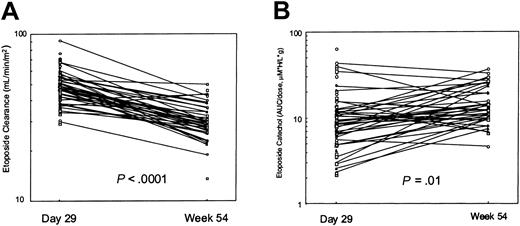

There were 41 patients (26 whites and 15 blacks) who had pharmacokinetic data at both day 29 and at week 54. The day 29 etoposide clearance (median, 47.4 mL/min/m2) was higher than that at week 54 (29.2 mL/min/m2; P < .0001; Figure 1A). Individually, 39 of the 41 patients had a higher etoposide clearance immediately following prednisone treatment. The smaller set of patients studied at week 19 (n = 6) also showed a significantly higher etoposide clearance at the time of prednisone treatment (median, 41.2 mL/min/m2 at week 19) than at week 54 (28.5 mL/min/m2; P < .05). The median in vivo inducibility index was 1.58 with a wide range (0.85-2.69). The “constitutive” etoposide clearance at week 54 was inversely correlated with age (Spearman rho = –0.50, P = .0003), but the induced clearance at day 29 was not (rho = –0.086, P = .371). The dose-normalized catechol AUC at day 29 was significantly less than that at week 54 (median, 11.0 versus 15.0 μM × h/L/g; P = .01; (Figure 1B). There was a positive correlation between etoposide AUC and catechol AUC at day 29 (rho = 0.319, P = .0008) but not at week 54 (rho = 0.16, P = .28). The ratio of catechol AUC to etoposide AUC did not differ significantly (P = .23) between day 29 (ratio = 0.015) and week 54 (ratio = 0.013).

Etoposide and catechol on and off prednisone. In 39 of 41 patients, etoposide clearance was higher at day 29 of therapy (after 28 days of glucocorticoid) than at week 54 (A). The dose-normalized etoposide catechol plasma AUC in 28 of these patients was lower at day 29 than at week 54 (B).

Etoposide and catechol on and off prednisone. In 39 of 41 patients, etoposide clearance was higher at day 29 of therapy (after 28 days of glucocorticoid) than at week 54 (A). The dose-normalized etoposide catechol plasma AUC in 28 of these patients was lower at day 29 than at week 54 (B).

Pharmacodynamics

The day 29 etoposide or catechol AUC was negatively correlated with the change in ANC (the ratio of the postetoposide ANC to the pre-etoposide ANC, n = 97, Spearman rho = –0.22, P = .027 for etoposide AUC; and rho = –0.34, P = .0008 for catechol AUC), but no correlations between AUCs and ANCs at week 54 were observed (n = 21; rho = –0.001, P = 1.00 for etoposide AUC; and rho = –0.03, P = .89 for catechol AUC).

Distribution of genotypes in the study group

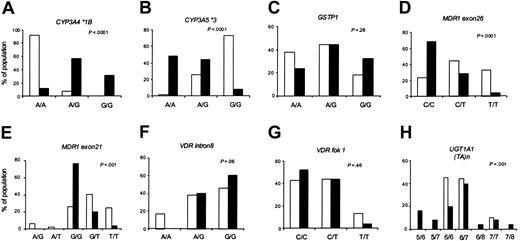

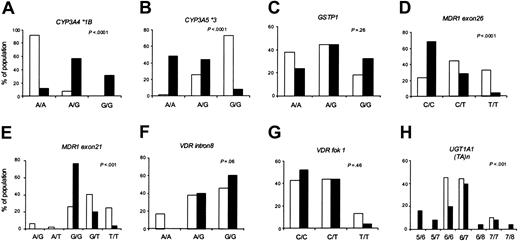

Allele frequencies differed significantly between black and white patients for 5 of the 8 loci (Figure 2). Within each racial group, the allele frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The genotypes were distributed similarly in the day 29 and week 54 patient subsets (data not shown).

Genotype frequencies by race. Using the set of patients evaluable at day 29 (n = 102; 77 whites and 25 blacks), the distribution of the indicated genotypes in whites (□) and blacks (▪) is compared.

Genotype frequencies by race. Using the set of patients evaluable at day 29 (n = 102; 77 whites and 25 blacks), the distribution of the indicated genotypes in whites (□) and blacks (▪) is compared.

Predictors of etoposide clearance

In univariate analyses, on prednisone (at day 29), and among whites, only the MDR1 exon 26 CC (P = .16) and MDR1 exon 21 GG (P = .20) genotypes were associated with higher etoposide clearance (see the Supplemental Table link at the top of the online article on the Blood website; Supplemental Table S1). Among blacks, only the CYP3A5 GG (P = .16) and GSTP1 AA (P = .016) genotypes were associated with lower etoposide clearance (Supplemental Table S1). For example, etoposide clearance was a median of 39.5 (n = 6), 48.8 (n = 11), and 51.4 mL/min/m2 (n = 8) among blacks with the GSTP1 AA, AG, and GG genotypes, respectively. Neither MDR1 genotype interacted with race, and stepwise multiple regression analysis showed MDR1 exon 26 to be an independent predictor of etoposide clearance at day 29 in patients of both races (P = .002, Table 2). No other genotypes were predictive of day 29 clearance in whites in the multivariate analysis. Among blacks, CYP3A5 (P = .022) and GSTP1 (P = .034) genotypes, together with age, were predictors of clearance (Table 2). The multivariate model explained 26% of overall variation in etoposide clearance in all patients.

At week 54, in the absence of prednisone, among whites, only the CYP3A4 AA (P = .16) and GSTP1 AA (P = .073) genotypes associated with lower clearance (Supplemental Table S1). Among blacks, the CYP3A5 AA (P = .17), UGT1A1 7/7 (P = .038), VDR intron 8 AA/AG (P = .051), and the VDR Fok 1 TT (P = .11) genotypes were associated with lower clearance (Supplemental Table S1). In the multivariate analysis, age was negatively correlated with etoposide clearance at week 54 in all patients of both races (P = .041; Table 3). There were no other statistically significant independent predictors among whites. Among blacks, UGT1A1 (P = .039), VDR intron 8 (P = .036), and VDR Fok 1 (P = .052) polymorphisms were additional predictors in the multivariate model (Table 3). The multivariate model explained 55% of overall variation in etoposide clearance at week 54.

Predictors of etoposide catechol AUC

In univariate analyses, on prednisone (at day 29), only the CYP3A4 AA genotype (P = .12 among whites and P = .049 among blacks) and the UGT1A1 7/7 genotypes (P = .001 among whites) were associated with higher catechol AUC (Supplemental Table S2). At week 54, in univariate analyses, only the UGT1A1 7/7 genotype (P = .16 among whites) and CYP3A5 AA (P = .045 among blacks) were associated with higher catechol AUC (Supplemental Table S2). For example, the median catechol AUC at day 29 was 7.5, 10.5, and 18.7 μM × h/L/g among those with UGT1A1 6/6, 6/7, and 7/7 genotypes, respectively. We found no interaction between race and the relationships between genotypes and catechol AUC. In the multivariate analyses, UGT1A1 7/7 genotype was a predictor of the catechol metabolite AUC in all patients of both races, with higher AUC in those with the low activity 7/7 genotypes, explaining 16% of overall variation on day 29 (P = .0013) and 14% of overall variation at week 54 (P = .03). Sex was also a weak predictor of the day 29 catechol AUC in all patients, with a tendency for higher AUC in girls (P = .07).

Discussion

We found that etoposide clearance was significantly higher in patients who had recently received glucocorticoid (prednisone) therapy. A few reports have addressed the influence of other drugs on etoposide pharmacokinetics,23,37,38 but this is the first study to assess the effects of glucocorticoid use. A possible explanation for our findings is that Pgp was induced by glucocorticoids. Pgp is a transporter of many anticancer agents, including etoposide. Glucocorticoids have been reported to induce expression of Pgp, to be substrates for Pgp, and to inhibit Pgp function18,19 —with varying results likely due to experimental differences in drug concentrations, tissue types, and confounding effects of other enzymes and transporters. If prednisone induced the expression of Pgp in the tissues involved in etoposide excretion (eg, biliary tract and renal tubules), its clearance would likely be increased. Consistent with this mechanism, the Pgp inhibitor cyclosporine was shown to decrease clearance of etoposide in adults39 and in children,40 suggesting that induction of Pgp (by prednisone) could have increased the clearance of etoposide.

It is known that CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 metabolize etoposide,7 and CYP3A can be induced by glucocorticoids,24,41-43 but it is not clear that induction of CYP3A4 or CYP3A5 by glucocorticoids was the cause of the increased etoposide clearance we observed at day 29. CYP3A can also be inhibited by glucocorticoids.7 If prednisone had induced the metabolism of etoposide to its catechol, the ratio of catechol to parent drug would have been expected to increase on prednisone compared to off prednisone, but it did not (P = .23). Thus, it is not clear that the increase in etoposide clearance with glucocorticoids is due to CYP3A induction. The smaller absolute catechol AUC we observed in patients receiving steroids may have reflected a decrease in the parental drug AUC, although the correlation between parental drug and metabolite AUCs was weak. Age was negatively correlated with constitutive, noninduced etoposide clearance (only at week 54). We speculate that young children may have a greater capacity to clear etoposide and may be less susceptible than older children and adults to induction of etoposide clearance by glucocorticoids, although the mechanism underlying such a difference is unknown.

The pharmacodynamic effects of etoposide on hematologic toxicity have been well documented.2-4 Our finding of the association between etoposide or catechol AUC and the change of ANC at day 29 is consistent with these reports, although the effects of the concomitantly administered drug, cytarabine, may have confounded these associations. Interestingly, the correlation between catechol metabolite AUC and the ANC change was stronger than that between etoposide AUC and the ANC change (Spearman rho = –0.34, P = .0008 versus rho = –0.22, P = .027), and the catechol is known to be pharmacologically active.10-13

In 5 of 8 polymorphic loci, the allele frequencies differed between white and black patients. We found that etoposide clearance (the phenotype) differed according to race in patients of the same apparent genotype. It appears that common germline polymorphisms influence etoposide disposition, especially in black patients. However, particularly in blacks, the relatively large number of genetic loci and small numbers of patients (especially in some genotypic subgroups) put us at risk of overestimation of genotype/phenotype associations (type 1 error).

Patients with the MDR1 exon 26 T allele tended to have lower etoposide clearance than patients with the CC genotype only when receiving steroids (Supplemental Table S1), with a lower inducibility index in the TT genotypes (data not shown). This finding suggests that clearance was not induced by steroids to the same extent in MDR1 exon 26 TT patients as in others. The association between MDR1 polymorphisms and phenotypic Pgp activity is somewhat controversial.44 The MDR1 exon 26 T allele has been associated with lower29,30,45 and with higher46 Pgp expression. If the MDR1 exon 26 TT genotype means higher Pgp expression, then one would predict lower oral bioavailability of prednisone, and therefore perhaps a lesser effect on inducibility of etoposide clearance (which is indeed what we observed). Alternatively, if the TT genotype means lower Pgp expression, then direct Pgp-mediated biliary or renal excretion of etoposide would be reduced, and thus clearance of etoposide could be lower. Our data are more consistent with the former interpretation because the MDR1 exon 26 polymorphism related only to etoposide clearance on prednisone, not in the uninduced state at week 54.

GSTP1 was an independent predictor of etoposide clearance in black patients receiving steroids; the presence of the lower activity G allele14 predicted a higher etoposide clearance. It is possible that inducibility by steroids was increased by the GSTP1 G allele, if low GST activity translated into greater exposure to prednisone and thus greater inducibility.

UGT1A1 was significantly associated with etoposide clearance at week 54 (not on steroids) in black patients and with catechol metabolite AUC in the entire group at both time points. The results of an in vitro assay suggested that UGT activity decreases as the number of (TA) repeats increases from 5 to 9,47 although the functional effects of the more rare (TA)5 and (TA)8 repeats is controversial. Etoposide is glucuronidated by UGT1A1,16 and glucuronidation of etoposide catechol has not yet been demonstrated. Our findings support the data that UGT1A1 is responsible for etoposide glucuronidation because greater glucuronidation in patients with the (TA)6 than (TA)7 alleles would be consistent with greater etoposide clearance.

VDR polymorphisms were associated with etoposide clearance in black patients not receiving glucocorticoids. VDR has been proposed to induce expression of CYP3A by coupling with the VDR-activated retinoid X receptor heterodimer to the CYP3A pregnane X receptor (PXR) response element and promoting CYP3A gene transcription.8 Transgenic mice expressing a constitutively active form of human PXR show markedly increased UGT activity.48 Hence, it is possible that VDR induces UGT1A1 as well as CYP3A, and VDR genetic polymorphisms may be associated with the difference in etoposide clearance in the black population.

We conclude that glucocorticoids are strong inducers of etoposide clearance. Germline polymorphisms may predict constitutive and glucocorticoid-inducible clearance of etoposide and its catechol metabolites, but the relationship between genotype and phenotype may differ by race or ethnicity.

Supported by National Cancer Institute grants CA 51001, CA 78224, and CA21765 and the NIH/NIGMS Pharmacogenetics Research Network and Database (U01 GM61393, U01GM61374) from the National Institutes of Health; by a Center of Excellence grant from the State of Tennessee; and by American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). C.-H.P. is the American Cancer Society F. M. Kirby Clinical Research Professor.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 11, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2105.

We thank our protocol coinvestigators, clinical staff, research nurses (Sheri Ring, Lisa Walters, Margaret Edwards, Terri Kuehner, and Paula Condy), and the patients and their parents for their participation. We also thank Dr Jean Cai, Pam McGill, and Nancy Duran for laboratory assistance and Nancy Kornegay and Carl Panetta for computing assistance.