Abstract

Sprouting angiogenesis is critical to blood vessel formation, but the cellular and molecular controls of this process are poorly understood. We used time-lapse imaging of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing vessels derived from stem cells to analyze dynamic aspects of vascular sprout formation and to determine how the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor flt-1 affects sprouting. Surprisingly, loss of flt-1 led to decreased sprout formation and migration, which resulted in reduced vascular branching. This phenotype was also seen in vivo, as flt-1-/- embryos had defective sprouting from the dorsal aorta. We previously showed that loss of flt-1 increases the rate of endothelial cell division. However, the timing of division versus morphogenetic effects suggested that these phenotypes were not causally linked, and in fact mitoses were prevalent in the sprout field of both wild-type and flt-1-/- mutant vessels. Rather, rescue of the branching defect by a soluble flt-1 (sflt-1) transgene supports a model whereby flt-1 normally positively regulates sprout formation by production of sflt-1, a soluble form of the receptor that antagonizes VEGF signaling. Thus precise levels of bioactive VEGF-A and perhaps spatial localization of the VEGF signal are likely modulated by flt-1 to ensure proper sprout formation during blood vessel formation. (Blood. 2004;103:4527-4535)

Introduction

The first step in the formation of most blood vessels is the production of an intricately branched vascular plexus.1-3 This plexus is subsequently pruned and remodeled and in some cases coalesced to form larger vessels. The primary branched plexus forms by several processes, including the initial assembly of vascular precursor cells called vasculogenesis, and the subsequent migration of endothelial cells from the parent vessel called sprouting angiogenesis. The sprouts that form migrate until they reach another sprout or vessel, whereupon they most often form connections that are essential for elaborating and expanding the branched network. Although the formation of vascular sprouts has been described historically,4-6 surprisingly little is known of the cellular processes and molecular controls of sprout formation, and even less is known about how these processes are integrated with other ongoing cellular events such as cell division.

The vascular sprouts that form during embryonic development extend from primitive vessels. Individual endothelial cells send out filopodia, then migrate away from the parent vessel without breaking all contacts with surrounding cells, so that eventually multiple cells comprise the sprout. Cell numbers in the sprout are also increased by cell division behind the leading tip of the sprout.6,7

Formation of a branched vascular plexus depends on the regulated expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) by nonendothelial cells. This signal modulates intracellular signaling pathways that regulate endothelial cell division, migration, and survival.8 This regulation is dose-dependent, as modest changes in the amount of available VEGF-A in either direction compromise vascular development, and loss of even one copy of the Vegf-A gene leads to vascular disruption and embryonic lethality.9-13 Availability also seems to be regulated by the production of different isoforms of VEGF-A via alternative splicing. These isoforms have differing affinities for matrix components, and disruption of individual isoforms affects vessel morphogenesis.14-16

VEGF-A signals through 2 receptor tyrosine kinases, flk-1 (VEGFR2) and flt-1 (VEGFR1). VEGF/flk-1 interactions positively influence endothelial chemotaxis and proliferation, but the outcomes of VEGF/flt-1 interactions are less clearcut.17,18 The flt-1 gene encodes both a receptor tyrosine kinase (membrane flt-1 [mflt-1]) and a secreted splice variant, sflt-1, which consists of the flt-1 extracellular domain. The sflt-1 protein binds VEGF-A with high affinity and is a potent antagonist of VEGF/flk-1 signaling.19,20 Mouse mutants lacking flt-1 die at embryonic day 9.5 with highly disorganized blood vessels and excess endothelial cells,21 yet a mouse with a modified flt-1 gene that lacks most of the cytoplasmic domain is viable,22 suggesting that sflt-1 is sufficient for the developmental role of flt-1. We recently showed that flt-1 negatively modulates endothelial cell division,23 but the role of flt-1 in endothelial cell migration remains unclear. In vitro studies, including analysis of chimeric VEGF receptors, failed to demonstrate a role for flt-1 in endothelial migration.17,18,24-26 However, a study in which VEGF/flt-1 binding was selectively blocked suggested that flt-1 promotes VEGF-dependent actin reorganization and migration.27

In the course of investigating the effects of a flt-1 null mutation on blood vessel formation, we noticed aberrant morphogenesis of flt-1-/- embryonic vessels.23 Thus we reasoned that flt-1 might modulate the VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration that occurs during embryonic sprouting angiogenesis. Our use of confocal time-lapse imaging afforded us the unique ability to analyze dynamic processes of mammalian vascular development. Vascular sprout formation was analyzed in wild-type and flt-1-/- mutant embryonic stem (ES) cells induced to differentiate to form primitive vessels. To our surprise, flt-1-/- blood vessels exhibited decreased sprout formation, and the flt-1-/- mutant sprouts that formed had a reduced migration rate. Moreover, flt-1-/- embryos showed defective sprouting of vessels from the dorsal aorta. This defect is likely not an immediate consequence of increased endothelial cell division in the mutant background, since the sprouting defect persisted after endothelial cell division rates returned to normal in flt-1-/- mutant vessels. Rather, rescue of the mutant phenotype with an sflt-1 transgene suggests a model whereby sflt-1 protein interacts locally with VEGF-A. This interaction is predicted to establish or modify a gradient that regulates vascular sprouting and endothelial cell migration.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and in vitro differentiation

Wild-type (WT; +/+) and flt-1-/- ES cells21 containing an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) or an sflt-1 transgene under the transcriptional control of the platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) promoter/intron enhancer element (P. Robson, D. Song, C.E., V.L.B., and H. S. Baldwin, manuscript in preparation) were maintained and differentiated in vitro as described previously.28 Cultures were plated onto slide flasks (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) at day 3 of differentiation and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 until time-lapse imaging was performed.

DNA constructs and electroporation

The PECAM promoter/enhancer (gift of H. S. Baldwin; P. Robson, D. Song, C.E., V.L.B., and H. S. Baldwin, manuscript in preparation) was cloned into a modified eGFP vector (BD Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) for electroporation into WT ES cells and designated PECAM-eGFP. PGKHygro (gift of N. Maeda) was then inserted into the PECAM-eGFP vector for electroporation into flt-1-/- ES cells and designated PECAM-eGFP-Hygro. The sflt-1 cDNA was generated by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification of a 500-base pair (bp) fragment of sflt-1 (nucleotides [nt's] 1834-2544) from WT day-8 ES cell cultures, which was cloned via the TA method (Promega, Madison, WI) and verified by sequence analysis. A 2.1-kbp XbaI fragment from mflt9 (mouse flt-1 cDNA; gift of G. Breier29 ) that encompassed nt's 1-2134 of full-length flt-1 was cloned into the unique XbaI site at position 2134 of the sflt-1 clone. The sflt-1 cDNA was cloned into the PECAM-Hygro vector and designated PECAM-sflt-1.

Twenty micrograms of linearized PECAM-eGFP and PECAM-eGFP-Hygro DNAs were electroporated into 2 × 107 ES cells using a BioRad GenePulser II electroporator (250 V/300 μF; BioRad, Hercules, CA). WT ES cell selection was in 200 μg/mL G418 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), and selection of flt-1-/- ES cells was in 200 μg/mL hygromycin B (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). After 10 to 12 days, drugresistant ES colonies were picked, expanded, and analyzed. We initially analyzed 3 WT transgenic lines (designated as WT; Tg pecam-egfp) and 4 flt-1-/- transgenic lines (designated as flt-1-/-; Tg pecam-egfp) and saw no differences except by genotype, so single WT and mutant lines were used. PECAM-eGFP and PECAM-sflt-1 were linearized and electroporated into flt-1-/- ES cells at a 1:3 molar ratio. After selection in hygromycin B, drug-resistant ES colonies that expressed eGFP were picked and analyzed.

Time-lapse imaging and quantitative analysis

Slide flasks containing day-6 to -8 in vitro-differentiated ES cultures were sealed, then placed on a heated stage on a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope (Melville, NY) with a Perkin Elmer spinning disk confocal head (Shelton, CT). Confocal images were acquired at 1-minute intervals using Metamorph software (version 6.0; Universal Imaging Corp, Downing-town, PA) and a Hamamatsu Orca CCD camera (McHenry, IL) with a × 20 objective.30 Quantitative image analysis was performed using Metamorph software. For sprout index measurements, total vessel perimeter was determined by outlining vessels and measuring total line length. Sprouts were defined as endothelial cell projections that included cytoplasm and were at least 10 μm in length. For sprout velocity measurements, total sprout length was determined by measuring the distance from the tip of the sprout to the point at which the sprout joined the primary vessel wall. For cell division score measurements, average percentage of GFP-positive area was determined for each movie by thresholding and averaging 3 separate frames: the first, middle, and last frame. Significance was determined using the 2-tailed Student t test.

For fixed branch point analysis, cultures labeled with anti-PECAM antibody were photographed using a Nikon eclipse E800 upright microscope at × 10 magnification. Vessel length was determined by tracing a vascular skeleton and measuring total line length using Metamorph software. Branch points were identified by visual scoring of each frame.

Antibody and β-galactosidase staining

Following time-lapse imaging, ES cell cultures were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 5 minutes in ice-cold methanol-acetone (50:50). Fixed cultures were reacted with rat antimouse PECAM at 1:1000 (MEC 13.3; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and donkey antirat immunoglobulin G (IgG; H+L) TRITC (tetramethylrhodamine-5(and 6)-isothiocyanate) cross-absorbed at 1:100 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) antibodies as described previously.12,28 All cultures were viewed and photographed with an Olympus IX-50 inverted microscope (Melville, NY) outfitted with epifluorescence. PECAM images were aligned with the last frame of each movie using Photoshop version 5.5 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Cocultures were fixed and processed for β-galactosidase reactivity as described.23

Embryo manipulations

Flt-1+/- mice were intercrossed, and embryos were dissected at 8.5 dpc (days after coitus) and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C. Yolk sacs were used for genotyping as described.23 The next day embryos were dehydrated through a MeOH series then rehydrated and whole-mount stained for PECAM-1 as described.31 After staining, embryos were visualized and photographed on an Olympus SZH10 dissecting microscope.

Results

Dynamic image analysis of vascular sprout formation

To assay dynamic components of vascular morphogenesis, we generated stable ES cell subclones using a PECAM promoter/enhancer reporter in WT and flt-1-/- genetic backgrounds (see “Materials and methods” for details). A subset of drug-resistant subclones expressed eGFP in the endothelial lineage upon differentiation. Because subclones of the same genotype were phenotypically similar, we chose a single WT line (P27; WT-eGFP) and a single flt-1-/- line (GG5-15; flt-1-/--eGFP) for further analysis. To confirm that expression of the reporter recapitulated expression of endogenous PECAM, we fixed day-8 WT-eGFP and flt-1-/--eGFP ES cell differentiation cultures after time-lapse image analysis and stained for PECAM (Figure 1). These images were overlayed with the last GFP image filmed (Figure 1Aiii,vi,ix). The congruence of the images showed that the eGFP reporters were expressed in the same cells that also expressed endogenous PECAM, and in all cases expression was associated with blood vessels. While the majority of PECAM-positive cells were endothelial cells lining the vessels, a small number of cells within the vessels also expressed PECAM, and these are likely to be the subset of hematopoietic cells that are PECAM positive. The apparent lack of eGFP expression in a subset of PECAM-positive cells results from the comparison of confocal (Figure 1Ai,iv,vii) with epifluorescence (Figure 1Aii,v,viii) images, since confocal images had a thinner focal plane. These data also confirm that the vascular phenotypes of the eGFP-expressing ES cell subclones recapitulate the parental vascular phenotypes.23,32 Specifically, a branched vascular plexus was seen in WT-eGFP cultures (Figure 1Ai-iii), while both sheets of endothelial cells (Figure 1Avii-ix) and some branched areas (Figure 1Aiv-vi) were seen in the flt-1-/--eGFP cultures. Finally, these results confirm that the conditions of time-lapse imaging do not adversely affect vascular development in the ES cell cultures.

GFP expression allows for visualization of mammalian sprouting angiogenesis. Stable ES cell lines expressing PECAM-GFP were generated (see “Materials and methods”) and subjected to time-lapse image analysis of vascular processes for 4.5 to 9.5 hours. (A) Day-8 WT-eGFP (+/+, i-iii) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-, iv-ix) ES differentiation cultures were imaged by time-lapse at 1-minute intervals for 4.5 to 9.5 hours, then fixed and reacted with an anti-PECAM antibody. The last frame captured (i,iv,vii) was overlayed (iii,vi,ix) with the PECAM-stained image (ii,v,viii). Original magnification × 20. (B) Time-lapse frames of a day-8 WT-eGFP ES differentiation culture showing the formation of a vascular sprout and its fusion with another sprout. Time in minutes is at bottom left of each frame. The white arrowhead indicates sprout formation and extension; the white arrow, the fusion of the sprout tip with the second sprout. Scale bar in panel B is 20 μm (Supplemental Movie S1).

GFP expression allows for visualization of mammalian sprouting angiogenesis. Stable ES cell lines expressing PECAM-GFP were generated (see “Materials and methods”) and subjected to time-lapse image analysis of vascular processes for 4.5 to 9.5 hours. (A) Day-8 WT-eGFP (+/+, i-iii) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-, iv-ix) ES differentiation cultures were imaged by time-lapse at 1-minute intervals for 4.5 to 9.5 hours, then fixed and reacted with an anti-PECAM antibody. The last frame captured (i,iv,vii) was overlayed (iii,vi,ix) with the PECAM-stained image (ii,v,viii). Original magnification × 20. (B) Time-lapse frames of a day-8 WT-eGFP ES differentiation culture showing the formation of a vascular sprout and its fusion with another sprout. Time in minutes is at bottom left of each frame. The white arrowhead indicates sprout formation and extension; the white arrow, the fusion of the sprout tip with the second sprout. Scale bar in panel B is 20 μm (Supplemental Movie S1).

We next asked whether a specific morphogenetic behavior, the formation of a vascular sprout, was recapitulated in ES cell differentiation cultures (Figure 1B and Supplemental Movie S1, available at the Blood website; see the Supplemental Movies link at the top of the online article). Day-8 WT-eGFP ES differentiation cultures were imaged for 2 to 10 hours. The resulting images were examined for sprout formation, as defined by projections from the parent structure that were at least 10 μm in length and were GFP-positive. Numerous examples of sprout formation were noted, and one example is shown in Figure 1B. This sprout initiated, extended, and formed a connection with a sprout from another area within a 145-minute period. The eGFP reporter did not allow for precise location of cell boundaries, but the sprout length was approximately 20 μm at maximum, suggesting that it was composed of one or at most 2 endothelial cells. Most sprouts that formed in WT cultures either joined with another sprout or part of a vessel, or they remained in place as sprouts at the end of filming (Figure 2A; data not shown). Rarely, sprouts formed and retracted during the period of filming. These results show that ES cell differentiation is an appropriate model system for visualization and analysis of vascular morphogenetic processes in the mammal.

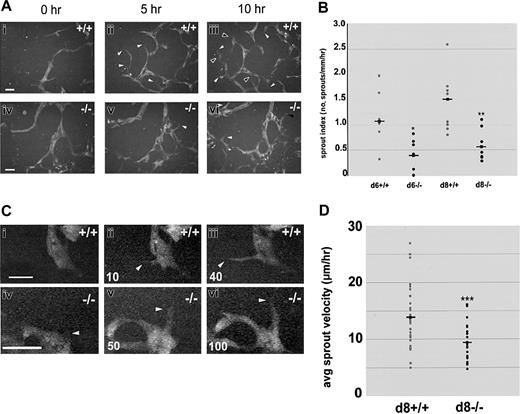

Sprout formation and migration are reduced in the absence of flt-1 Day-8 WT-eGFP (+/+; Ai-iii, Ci-iii) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-; Aiv-vi, Civ-vi) ES differentiation cultures were imaged by time-lapse at 1-minute intervals for the indicated times. (A) Over a 10-hour period, numerous new WT sprouts (i-iii) formed (white arrowheads) and remained or extended and/or fused at later times (black arrowheads), whereas very few flt-1-/- sprouts (iv-vi) formed during the same time period. Scale bar is 20 μm (Supplemental Movies S2-S3). (B) Movie frames were analyzed to determine a sprout index (no. of sprouts/mm/h) for multiple movies on day 6 (d6) or day 8 (d8) of differentiation. Gray dots indicate WT-eGFP sprout indices; black dots, flt-1-/--eGFP sprout indices; and squares with lines, the average of each group. *P < .03; **P < .01. (C) Over a 40-minute period, a WT sprout formed and extended between 30 and 40 μm, while over a 100-minute period a flt-1-/- mutant sprout formed and extended only 20 μm. White arrowheads point to sprout tips, and time in minutes is at bottom left. Scale bar = 20 μm (Supplemental Movies S4-S5). (D) Movie frames were analyzed to determine average sprout velocity (μm/h) for multiple sprouts from different movies on day 8 (d8) of differentiation. Gray dots indicate WT-eGFP average sprout velocities; black dots, flt-1-/--eGFP average sprout velocities; and squares with lines, the average of each group. ***P < .001.

Sprout formation and migration are reduced in the absence of flt-1 Day-8 WT-eGFP (+/+; Ai-iii, Ci-iii) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-; Aiv-vi, Civ-vi) ES differentiation cultures were imaged by time-lapse at 1-minute intervals for the indicated times. (A) Over a 10-hour period, numerous new WT sprouts (i-iii) formed (white arrowheads) and remained or extended and/or fused at later times (black arrowheads), whereas very few flt-1-/- sprouts (iv-vi) formed during the same time period. Scale bar is 20 μm (Supplemental Movies S2-S3). (B) Movie frames were analyzed to determine a sprout index (no. of sprouts/mm/h) for multiple movies on day 6 (d6) or day 8 (d8) of differentiation. Gray dots indicate WT-eGFP sprout indices; black dots, flt-1-/--eGFP sprout indices; and squares with lines, the average of each group. *P < .03; **P < .01. (C) Over a 40-minute period, a WT sprout formed and extended between 30 and 40 μm, while over a 100-minute period a flt-1-/- mutant sprout formed and extended only 20 μm. White arrowheads point to sprout tips, and time in minutes is at bottom left. Scale bar = 20 μm (Supplemental Movies S4-S5). (D) Movie frames were analyzed to determine average sprout velocity (μm/h) for multiple sprouts from different movies on day 8 (d8) of differentiation. Gray dots indicate WT-eGFP average sprout velocities; black dots, flt-1-/--eGFP average sprout velocities; and squares with lines, the average of each group. ***P < .001.

Sprout formation and function is compromised in the absence of flt-1

To determine how flt-1 affects vascular morphogenesis at the cellular level, we next compared sprout formation between WT and flt-1-/- vessels using dynamic image analysis (Figure 2A-B; Supplemental Movies S2-S3). Because flt-1-/- ES cell cultures had areas of endothelial sheets, we were careful to score mutant sprout formation only in areas of flt-1-/- ES cell cultures that contained a vascular plexus (Figure 1Aiv-vi; Figure 2Aiv-vi). To measure sprout formation, a sprout index that was normalized for time and vessel perimeter was calculated for multiple movies of each genotype. Since the lack of flt-1 leads to increased rates of endothelial cell division via up-regulation of VEGF signaling,23,33 we hypothesized that morphogenetic parameters such as sprout formation would also be increased in the flt-1-/- genetic background. To our surprise, flt-1-/- vessels had a reduced sprout index relative to WT vessels. The sprout indices for day-6 and day-8 WT-eGFP time-lapse movies (Figure 2B, gray circles) had a wider distribution that ranged much higher than day-matched flt-1-/--eGFP movies (Figure 2B, black circles). Furthermore, flt-1-/--eGFP vessels showed a 2.5-fold decrease in average sprout formation index over day-matched WT controls. These results show that flt-1-/- blood vessels sprout less often than WT blood vessels.

We next determined whether the absence of flt-1 affects the rate of sprout migration. Analysis of time-lapse images was used to determine average sprout velocity (sprout vessel tip displacement/time) for flt-1-/--eGFP vascular sprouts and WT control sprouts (Figure 2C-D; Supplemental Movies S4-S5). Sprout vessel tips (Figure 2C, white arrowheads) were tracked over time using the base of the sprout at each time as the reference point. A plot of the average velocity for individual sprouts (Figure 2D) showed that flt-1-/--eGFP sprouts (black circles) displayed a lower range of velocities than WT-eGFP sprouts. Moreover, flt-1-/--eGFP sprouts had a mean average sprout velocity that was reduced by 36% compared with WT-eGFP sprouts. This result indicates that flt-1 also modulates the speed with which sprouts migrate along a vector once they form.

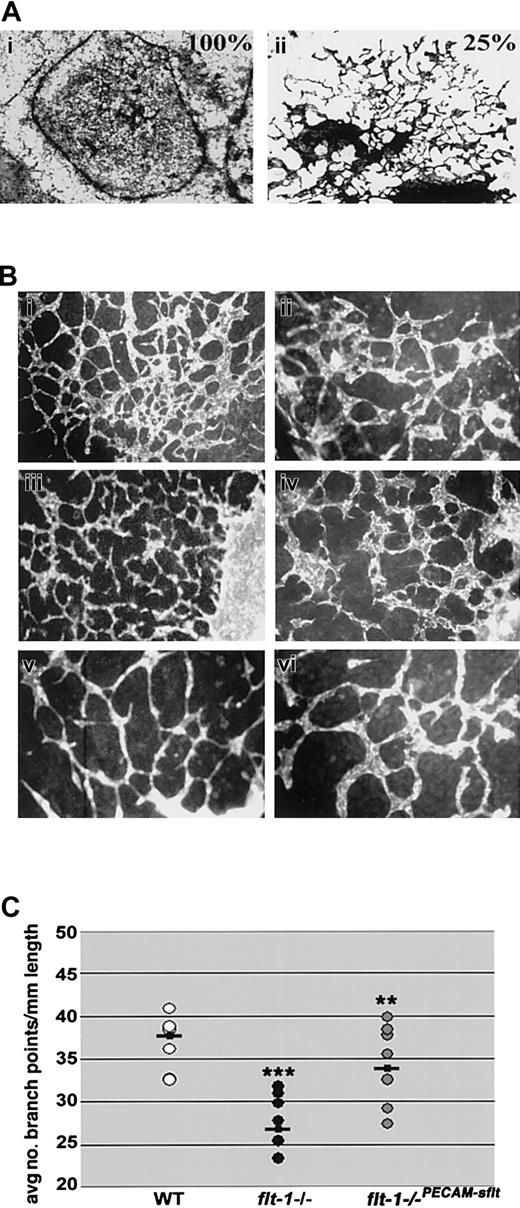

We confirmed these results with a more traditional assay that is reflective of sprout formation: branch point analysis. Fixed samples of day-8 WT-eGFP and flt-1-/--eGFP differentiated ES cell cultures were labeled with PECAM to visualize vessels (Figure 3). The flt-1-/--eGFP and WT-eGFP vascular plexuses showed a range of branch point densities (Figure 3A), but flt-1-/--eGFP ES cell cultures had less complex networks of blood vessels on average than WT controls (compare Figure 3Ai-iii with iv-vi). Quantitation showed that flt-1-/--eGFP ES cell cultures had a 30% to 40% decrease in branch point formation relative to WT (Figure 3B). Thus, the fixed branch point data are consistent with the time-lapse data, and they support a model whereby flt-1 normally modulates vessel morphogenesis by positively regulating both the frequency of endothelial sprout formation and the rate of sprout migration.

Branching morphogenesis is reduced in the absence of flt-1 Day-8 WT-eGFP (+/+; Ai-iii) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-; Aiv-vi) ES differentiation cultures were fixed and reacted with an anti-PECAM antibody. (A) Note that while each genotype had a range of branching complexities, on average less complexity was seen in the flt-1-/--eGFP cultures. Scale bar is 50 μm. (B) The average number of branch points per millimeter of vessel length was determined using 10 fields of each genotype in 2 experiments and expressed as a percentage of wild-type branching. ***P < .001.

Branching morphogenesis is reduced in the absence of flt-1 Day-8 WT-eGFP (+/+; Ai-iii) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-; Aiv-vi) ES differentiation cultures were fixed and reacted with an anti-PECAM antibody. (A) Note that while each genotype had a range of branching complexities, on average less complexity was seen in the flt-1-/--eGFP cultures. Scale bar is 50 μm. (B) The average number of branch points per millimeter of vessel length was determined using 10 fields of each genotype in 2 experiments and expressed as a percentage of wild-type branching. ***P < .001.

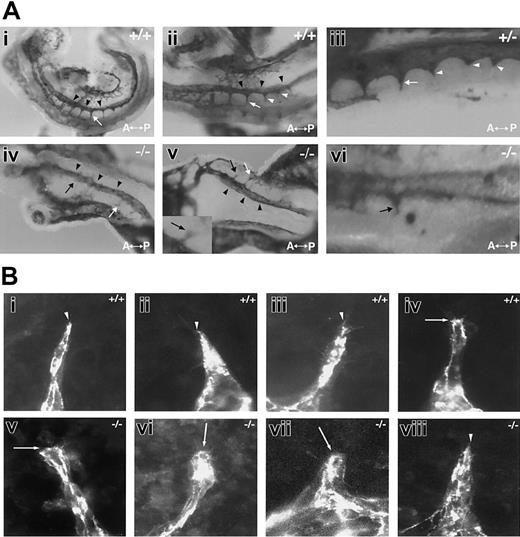

To determine if the reduced sprout formation seen in the absence of flt-1 was also seen in vivo, we examined the formation of intersomitic vessels that arise via sprouting angiogenesis from the dorsal aorta (Figure 4A). At 8.5 dpc, wild-type embryos consistently had several intersomitic vessels, and well-defined vascular sprouts were seen in register posterior to the vessels (Figure 4Ai-iii). In contrast, day-matched flt-1-/- embryos had very few intersomitic sprouts, and those that formed were short and seldom connected to the vertebral vessel (Figure 4Aiv-vi). Thus the sprout defect documented in vascular development in ES differentiation cultures is also seen in mutant embryos lacking flt-1.

Sprouting from the dorsal aorta is reduced in the absence of flt-1 (A) The 8.5-dpc embryos that were WT (+/+; i-ii), flt-1+/- (+/-; iii), or flt-1-/- (-/-; iv-vi) were collected and whole-mount stained with an anti-PECAM antibody. (i-iii) In 3 different normal embryos, intersomitic vessels (white arrows) branch from the dorsal aorta (black arrowheads). A magnified view in panel iii shows several intersomitic sprouts (white arrowheads) in register posterior to the vessels. (iv-vi) Two different flt-1-/- embryos show few branches from the dorsal aorta, and those that are seen are often stunted (black arrows). The inset in panels v and vi show stunted sprouts with blunted tips. A indicates anterior; and P, posterior. Original magnification × 5. (B) Day-8 WT (i-iv) and flt-1-/- (v-viii) ES differentiation cultures were fixed and stained with a PECAM antibody. Representative sprouts were photographed. Note that most WT sprouts are tapered at the distal end (white arrowheads), while most flt-1-/- mutant sprouts are blunted (white arrows) at the distal end. Original magnification × 60.

Sprouting from the dorsal aorta is reduced in the absence of flt-1 (A) The 8.5-dpc embryos that were WT (+/+; i-ii), flt-1+/- (+/-; iii), or flt-1-/- (-/-; iv-vi) were collected and whole-mount stained with an anti-PECAM antibody. (i-iii) In 3 different normal embryos, intersomitic vessels (white arrows) branch from the dorsal aorta (black arrowheads). A magnified view in panel iii shows several intersomitic sprouts (white arrowheads) in register posterior to the vessels. (iv-vi) Two different flt-1-/- embryos show few branches from the dorsal aorta, and those that are seen are often stunted (black arrows). The inset in panels v and vi show stunted sprouts with blunted tips. A indicates anterior; and P, posterior. Original magnification × 5. (B) Day-8 WT (i-iv) and flt-1-/- (v-viii) ES differentiation cultures were fixed and stained with a PECAM antibody. Representative sprouts were photographed. Note that most WT sprouts are tapered at the distal end (white arrowheads), while most flt-1-/- mutant sprouts are blunted (white arrows) at the distal end. Original magnification × 60.

We reasoned that if sprout formation and migration were affected in the absence of flt-1, the endothelial cells at the tip of the sprout might have an abnormal morphology. Indeed, our examination of sprouts in flt-1-/- embryos suggested that sprout tips tend to be blunted in the absence of flt-1 (Figure 4Av inset,vi). To analyze this observation more carefully, we examined the morphologies of WT and flt-1-/- mutant sprouts in ES cell differentiation cultures (Figure 4B). WT sprout tips in general gradually tapered to a point, although rare WT sprouts were less tapered (Figure 4Bi-iv). In contrast, more of the flt-1-/- mutant sprout tips were blunted (Figure 4Bv-viii), consistent with our findings that sprout migration along a vector is reduced.

Cell division defects are not immediately upstream of morphogenesis defects in flt-1-/- mutant vessels

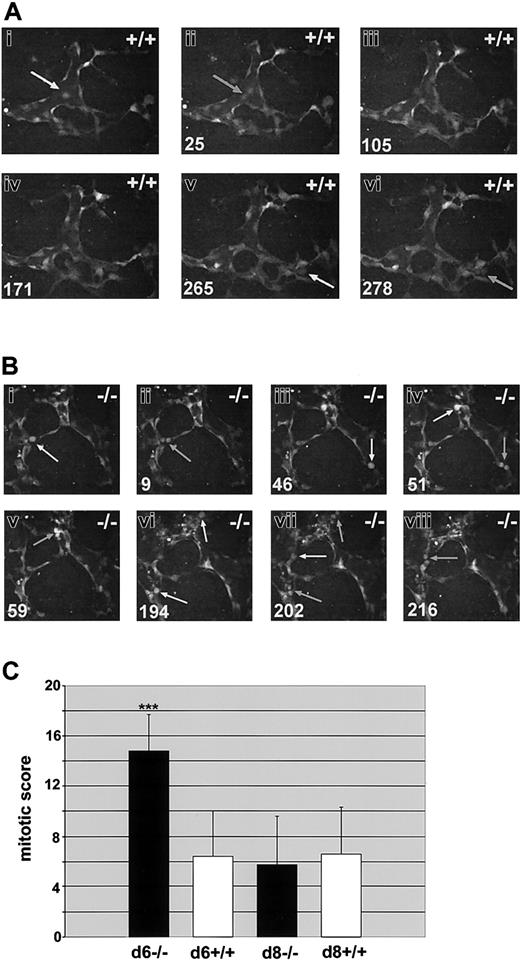

We previously showed that flt-1-/- ES cultures display a 2- to 3-fold increase in endothelial cell division on day 6 of differentiation.23 To determine if this difference was also observed with dynamic image analysis, we scored endothelial cell mitoses in flt-1-/--eGFP ES cell differentiation cultures and in WT controls (Figure 5; and Supplemental Movies S6-S7). Day-6 flt-1-/--eGFP cultures had increased numbers of mitotic endothelial cells compared with WT controls (compare Figure 5A and 5B). The number of endothelial cell divisions per hour was normalized for vascular area and used to produce a mitotic score that was averaged for multiple movies of both genotypes (Figure 5C). Day-6 flt-1-/--eGFP vessels had an average mitotic score that was increased over WT-eGFP vessels by more than 2-fold, consistent with our previous results.23 However, the differences in mitotic score between WT and flt-1-/- mutant vessels were resolved by day 8, a time point that was not assayed in our original study.

Endothelial cell divisions are increased in the absence of flt-1 Day-6 WT-eGFP (+/+;A) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-; B) ES differentiation cultures were imaged by time lapse at one-minute intervals for the indicated times. Day-8 cultures of both genotypes were also imaged for quantitation (C). (A-B) Endothelial cell predivision rounding up is denoted by white arrows, and cytokinesis is denoted by gray arrows. Time in minutes is at the bottom left. Note that over a similar time span there are more divisions scored in the flt-1-/- mutant vessels (Supplemental Movies S6-S7). Original magnification × 20. (C) Time-lapse movies from day-6 WT-eGFP (n = 6), day-6 flt-1-/--eGFP (n = 8), day-8 WT-eGFP (n = 8), and day-8 flt-1-/--eGFP (n = 8) were analyzed for a mitotic score (no. of endothelial cell divisions/eGFP-positive area/h). ***P < .001.

Endothelial cell divisions are increased in the absence of flt-1 Day-6 WT-eGFP (+/+;A) or flt-1-/--eGFP (-/-; B) ES differentiation cultures were imaged by time lapse at one-minute intervals for the indicated times. Day-8 cultures of both genotypes were also imaged for quantitation (C). (A-B) Endothelial cell predivision rounding up is denoted by white arrows, and cytokinesis is denoted by gray arrows. Time in minutes is at the bottom left. Note that over a similar time span there are more divisions scored in the flt-1-/- mutant vessels (Supplemental Movies S6-S7). Original magnification × 20. (C) Time-lapse movies from day-6 WT-eGFP (n = 6), day-6 flt-1-/--eGFP (n = 8), day-8 WT-eGFP (n = 8), and day-8 flt-1-/--eGFP (n = 8) were analyzed for a mitotic score (no. of endothelial cell divisions/eGFP-positive area/h). ***P < .001.

One explanation for the decreased frequency of sprout formation in the absence of flt-1 is the possibility that the increased rate of cell division precludes sprout formation and migration. The fact that day-8 flt-1-/--eGFP cultures had the same mitotic score as day-matched WT controls, whereas the sprout index and sprout velocity were still significantly decreased at day 8 in the flt-1-/- mutant vessels, suggests that this simple explanation is not valid. Time-lapse analysis provided the opportunity to observe the temporal and spatial positioning of endothelial cell divisions relative to sprout formation and maturation (Table 1). The sprout field was defined as the area of the primary vessel wall that would in the near future give rise to a sprout and the sprout itself. The rest of the structure was classified as primary vessel. Significant cell divisions occurred in the sprout field, and we even saw rare divisions in the distal-most tip cell of the sprout in both wild-type and flt-1-/- mutant vessels (data not shown), indicating that cell division and sprout formation/migration are not mutually exclusive over time. Moreover, the distribution of mitoses between the primary vessel and the sprout field was similar between WT and flt-1-/- mutant vessels on both days, indicating that the flt-1 mutation does not change the distribution of endothelial mitoses.

Aberrant flt-1-/- vascular morphogenesis is rescued in a non-cell-autonomous manner and with an sflt-1 transgene

To begin to determine the mechanism whereby flt-1 positively affects vascular morphogenesis, we asked whether sflt-1, the soluble antagonist of VEGF signaling, was generated coincident with vascular morphogenesis during ES cell differentiation. Day-8 wild-type and flt-1+/- heterozygous ES differentiation cultures expressed sflt-1 RNA and protein, and as predicted both RNA and protein were undetectable in day-matched flt-1-/- ES differentiation cultures (data not shown). We reasoned that if flt-1 positively regulates sprout formation via effects of the sflt-1 protein, it might be possible to rescue the morphogenetic defect in flt-1-/- vessels in a non-cell-autonomous manner. To test this hypothesis, we cocultured wild-type and flt-1-/- mutant embryoid bodies (EBs) in the same wells, by allowing EBs of both genotypes to attach on day 3 and continue differentiation to day 8 (Figure 6A). In contrast to flt-1-/- vessels that consisted of large sheets with a few sprouts at the edges, flt-1-/- vessels in wells with wild-type EBs (ratio of 3 WT to 1 mutant) showed areas of significant rescue and increased branching (compare Figure 6Ai to 6Aii). Thus the morphogenetic defect of flt-1-/- vessels can be rescued in a non-cell-autonomous manner, suggesting that sflt-1 and/or some other soluble component is critical to normal vascular morphogenesis.

The flt-1-/- phenotype is partially rescued non-cell-autonomously and by an sflt-1 transgene. (A) Coculture analysis. Day-3 EBs were plated in wells so that (i) 100% were flt-1-/- mutant EBs or (ii) 75% were WT and 25% were flt-1-/- mutant EBs, and after attachment and incubation for a further 5 days, cultures were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity. Original magnification × 10. (B) Day-8 WT (Bi-ii), flt-1-/- transfected with a PECAM-sflt transgene (Biii-iv), and flt-1-/- (Bv-vi) ES differentiation cultures were fixed and reacted with an anti-PECAM antibody. Original magnifications × 10 (Bi,iii,v) and × 20 (Bii,iv,vi). Note that branching in flt-1-/-PECAM-sflt cultures more closely resembles WT than flt-1-/- cultures. (C) The average number of branch points per mm of vessel length was determined using multiple fields of each genotype. **P < .01, flt-1-/- versus flt-1-/-PECAM-sflt; ***P < .001, WT versus flt-1-/-.

The flt-1-/- phenotype is partially rescued non-cell-autonomously and by an sflt-1 transgene. (A) Coculture analysis. Day-3 EBs were plated in wells so that (i) 100% were flt-1-/- mutant EBs or (ii) 75% were WT and 25% were flt-1-/- mutant EBs, and after attachment and incubation for a further 5 days, cultures were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity. Original magnification × 10. (B) Day-8 WT (Bi-ii), flt-1-/- transfected with a PECAM-sflt transgene (Biii-iv), and flt-1-/- (Bv-vi) ES differentiation cultures were fixed and reacted with an anti-PECAM antibody. Original magnifications × 10 (Bi,iii,v) and × 20 (Bii,iv,vi). Note that branching in flt-1-/-PECAM-sflt cultures more closely resembles WT than flt-1-/- cultures. (C) The average number of branch points per mm of vessel length was determined using multiple fields of each genotype. **P < .01, flt-1-/- versus flt-1-/-PECAM-sflt; ***P < .001, WT versus flt-1-/-.

To directly address the role of sflt-1 in vascular morphogenesis, we reintroduced sflt-1 into flt-1-/- ES cells. A PECAM-sflt-1 transgene was expressed in day-8 flt-1-/-PECAM-sflt cultures by RT-PCR (data not shown), and this was accompanied by a rescue of the mutant vascular phenotype (Figure 6B). A branch point analysis was performed, and the flt-1-/-PECAM-sflt cultures had rescued branching, with values that fell between WT and mutant cultures and that were significantly increased from flt-1-/- cultures (Figure 6C).

Discussion

Our results show that flt-1 modulates vascular sprout formation developmentally. To our surprise, this modulation is positive, and flt-1 is required for proper sprout formation and migration. The data that support this conclusion are: (1) the rate of sprout formation and migration are both decreased in the absence of flt-1, (2) decreased vascular branching accompanies loss of flt-1 during ES cell differentiation and is rescued by an sflt-1 transgene, and (3) decreased sprouting from the dorsal aorta results from loss of flt-1 in vivo. Our data support a model whereby flt-1 affects vascular morphogenesis via a soluble mediator that is likely to be sflt-1, suggesting that formation and/or modulation of a VEGF gradient may be important to the effect of flt-1 on vascular sprout formation (Figure 7).

Models of flt-1 modulation of VEGF signal-negative modulation results in net positive effect on sprout formation. We favor a model of flt-1 action on sprout formation that results from flt-1 binding VEGF-A and preventing binding to flk-1 (see “Discussion” for details). This could occur in several ways. (A) VEGF-Amay be deposited in a gradient between the producing tissue and the target vessel, and this unmodified gradient is not conducive to sprout formation in the absence of flt-1. (B) sflt-1 may be secreted and form a counter-gradient that modifies and steepens the VEGF-A gradient, leading to increased sprout formation. (C) mflt-1 and/or sflt-1 may locally decrease the availability of VEGF-A, leading to increased sprout formation.

Models of flt-1 modulation of VEGF signal-negative modulation results in net positive effect on sprout formation. We favor a model of flt-1 action on sprout formation that results from flt-1 binding VEGF-A and preventing binding to flk-1 (see “Discussion” for details). This could occur in several ways. (A) VEGF-Amay be deposited in a gradient between the producing tissue and the target vessel, and this unmodified gradient is not conducive to sprout formation in the absence of flt-1. (B) sflt-1 may be secreted and form a counter-gradient that modifies and steepens the VEGF-A gradient, leading to increased sprout formation. (C) mflt-1 and/or sflt-1 may locally decrease the availability of VEGF-A, leading to increased sprout formation.

How does flt-1 affect morphogenesis?

Since flt-1-/- endothelial cells have a higher rate of division than do wild-type endothelial cells,23 it was possible that the cell division defect was immediately upstream of the morphogenetic defect. That is to say, the endothelial cells possibly were too busy dividing to migrate. There is precedent for this model in that both normal and tumor vessels restrict cell divisions to sprout areas more proximal to the parent vessel,6,7,34 suggesting that actively migrating and sensing cells are prevented from dividing. Moreover, in tubulogenesis in the fly trachea, the tracheal precursor cell pool divides to produce all the tracheal cells, which then migrate and form the tracheal tubes in the absence of further cell division.35

Our use of time-lapse image analysis allowed us to determine the relationship between cell division and cell migration with finer resolution than with end-point analyses, and it showed that endothelial cells in a migratory mode can also undergo cell division. The cells did not migrate during mitosis or for some time prior to mitosis, but once division was complete the daughter cells often migrated quite rapidly to resume sprout formation. We found that divisions were not excluded from the “sprout field” but in fact were in most cases enriched in the sprouts and their vicinity (N.C.K. and V.L.B., unpublished results), suggesting that sprout formation may stimulate cell division. We even on occasion saw the most distal cell of the sprout undergo mitosis in both WT and flt-1-/- mutant vessels, although this event did not occur with high frequency. This finding differs from a recent study that found no tip cell division in retinal vessels.34 However, retinal vessels track along a VEGF template provided by astrocytes, while in our model and in many developmental vascular beds the source of VEGF is likely to be more diffuse. Thus sprouts may have distinct phenotypes in response to different presentations of agonist. Finally, we saw no difference in the distribution of cell divisions to different areas of the vessel in the flt-1-/- vessels compared with controls, indicating that flt-1 does not regulate this parameter of cell division. It is formally possible that aberrant cell division in flt-1-/- mutant vessels somehow compromises sprout formation, since there are more endothelial cell divisions in the flt-1 mutant background. However, the observation that the sprouting defects persist at day 8, when the rate of cell division in mutant vessels has returned to wild-type levels, strongly suggests that the effect of flt-1 on sprout formation and extension is independent of cell division.

Flt-1 is a negative regulator of VEGF-A/flk-1 signaling,19,33 and VEGF-A and flk-1 are both expressed during ES cell differentiation and required for vessel formation.12,36 Thus the flt-1-/- mutant vessels were expected to have increased sprout formation and migration. Instead, flt-1-/- mutant sprouts formed less frequently and had slower migration rates. There are several models that are consistent with this phenotype. Perhaps VEGF signaling through the flt-1 receptor (mflt-1) positively modulates endothelial cell migration developmentally, and the absence of this receptor in flt-1 mutants blocks this positive migratory pathway. VEGF/flt-1 signaling induces actin reorganization in cultured endothelial cells,27 the flt-1 kinase domain interacts with proteins involved in cell migration,37 and a VEGFR1-blocking antibody decreases capillary connections in vitro.38 However, a mouse model that lacks the flt-1 kinase domain shows normal vascular development, and stimulation of retinal vessels with placental growth factor (PlGF), which binds flt-1 but not flk-1, did not affect filopodia formation.22,34 These findings suggest that signaling through the flt-1 receptor is not required for proper sprout formation developmentally.

Another possible model to explain reduced sprouting in the absence of flt-1 is that mflt-1 and/or sflt-1 negatively modulate local interactions between VEGF-A and flk-1 that are important for migration (Figure 7). Flk-1 mediates VEGF-dependent endothelial cell migration, and VEGF/flk-1 signaling affects focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src, molecules involved in focal adhesion signaling and turnover.24,39-41 VEGF/flk-1 signaling also up-regulates the activity of the small guanine 5′-triphosphatase (GTPase) Rho,42,43 whose levels and spatial distribution are critical to proper migration as well.44,45 Indeed, recent work shows that cell migration involves the proper balance of adhesion and retraction of a cell, and imbalance in either parameter can impede movement.46,47 Thus the increased flk-1 signaling in flt-1-/- endothelial cells may lead to deregulation of Rho and/or focal adhesion turnover and thereby inhibit endothelial cell migration and sprout formation.

A model of vascular sprout formation

Our data are most consistent with a model of vascular sprout formation in which flt-1 normally negatively regulates the amount of VEGF-A that is available to interact with the flk-1 receptor, and this regulation provides the proper balance for a net positive effect on sprout formation and migration. Moreover, we show that the flt-1-/- morphogenetic defect can be rescued in a non-cell-autonomous manner, that sflt-1 is expressed appropriately to effect this rescue, and that an sflt-1 transgene expressed via the PECAM promoter/enhancer can significantly rescue the aberrant branching. Thus, although we cannot exclude a role for surface-localized mflt-1 in regulating the availability of VEGF-A, it is likely that sflt-1 is the primary molecular mediator of sprout formation from the flt-1 locus (Figure 7).

In our model, sflt-1 is produced by endothelial cells and secreted into the local milieu, where it can interact with local sources of VEGF-A. VEGF-A secretion from nonendothelial cells induces migration toward the source of the signal. It is possible that sflt-1 forms a protein gradient emanating from endothelial cells that interacts with VEGF-A to set up an effective VEGF gradient, or it could steepen an existing gradient (Figure 7B). sflt-1 binds heparin via IgG domain 4,48 so it may bind the matrix and thus form a gradient. Alternatively, sflt-1 could modulate a preexisting VEGF-A gradient without forming an independent gradient (Figure 7C). VEGF-A has 3 major isoforms that result from alternative splicing, and they have different biochemical properties. The VEGF120 isoform is completely diffusible, while the VEGF165 and VEGF188 isoforms are localized to the outer surface and surrounding matrix of VEGF-A-producing cells, although a significant fraction of VEGF165 diffuses from the cell.14 Thus these isoforms could produce a VEGF-A gradient by virtue of their differing affinities for matrix, and sflt-1 could impact this gradient. In this scenario, flt-1-/- mutant endothelial cells are inhibited from forming sprouts by exposure to excess VEGF-A (Figure 7A). Clearly, flt-1-/- mutant blood vessels do form sprouts, so while sflt-1 may modulate sprout formation and migration, it is not absolutely required for sprouting angiogenesis.

What is the evidence for this model? Spatially localized VEGF expression predicts branching morphogenesis in the embryonic lung.49 Analysis of retinal vessels in mouse mutants expressing only a single VEGF isoform demonstrates defects in vessel size and number, suggesting that the local availability and diffusion of VEGF-A protein is critical for vascular patterning during angiogenesis.15 A further analysis of VEGF isoform-selective mice provides evidence that a VEGF-A gradient set up in the hindbrain is compromised in the absence of matrix-bound VEGF.16 Moreover, inappropriate amounts of VEGF-A negatively affect sprout formation. Exogenous VEGF-A165 injected into quail embryos inhibits the formation and branching of intersomitic vessels from the dorsal aorta,50 similar to the effects seen in the flt-1-/- mutant embryos in our study. A recent study in the eye showed that increased levels of each VEGF isoform led to reduced filopodia length and reduced expansion of the retinal vascular plexus.34 These results suggest that excess VEGF-A leads to a perturbed endothelial migratory response, perhaps by disruption of a VEGF-A gradient, and support a model whereby flt-1 negatively modulates local availability of VEGF-A to positively affect sprout formation.

The use of soluble receptors to modulate the activity of soluble ligands is not exclusive to the VEGF-A pathway. Other growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), morphogens such as Wingless/Wnt, and vascular modifiers such as the angiopoietins, have soluble receptors of high affinity that can negatively modulate their respective signaling pathways.51-55 Indeed, the soluble receptor frizzled-related protein (Frzb) is thought to form gradients that modulate the availability of Wingless to target cells.52 Thus, this molecular mechanism of signal regulation is conserved in other signaling pathways.

Conclusions

We have identified a novel role for flt-1 in vascular morphogenesis, as a positive regulator of sprout formation and migration. This role is independent of a negative modulatory effect on endothelial cell division. We propose a model in which flt-1 positively affects sprout formation by negatively controlling the amount of VEGF-A signal that is sensed by endothelial cells, using sflt-1 as the primary mediator of the effect. We also suggest that gradient formation, either by VEGF-A or sflt-1 or both proteins, may be important in modulating sprout formation and migration. In any case, these results have implications for the development of disease therapies and for reconstruction of vessels. Clearly, the local availability of VEGF-A signal is critical to proper morphogenesis, and the regulation of this availability under normal conditions appears complex. Thus a better understanding of how this is accomplished will allow for better design of regimens for vessel reconstitution.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 24, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2315.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL71993 and HL43174 (V.L.B.); a Department of Defense (DOD) predoctoral fellowship (J.B.K.); NIH Training Grant T32-HL69768 and an American Heart Association (AHA) predoctoral fellowship (N.C.K.); and postdoctoral support from The Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT) and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (C.E.).

J.B.K. and N.C.K. contributed equally to this work.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Guo Hua Fong for the flt-1+/- and flt-1-/- ES cells and for the flt-1+/- mice, Georg Breier for the mouse flt-1 cDNA, Nobuyo Maeda for the PGK-Hygro construct, and Scott Baldwin for making available the PECAM promoter/enhancer prior to publication. We thank the Bautch Lab members and the Carolina Cardiovascular Development Group for fruitful discussions.

Supplemental data

A 10-hour time-lapse video of day-8 flt-1-/--eGFP ES differentiation culture that illustrates typical levels of sprout formation in flt-1-/- vessels. Notice how very few flt-1-/- sprouts form relative to the wild-type culture (Movie S2). Each frame corresponds to a single exposure; exposures were taken at one-minute intervals.

A 278-minute time-lapse video of day-6 WT-eGFP ES differentiation culture displaying typical levels of endothelial cell division in day-6 wild-type cultures. Note that over a similar time span there are more divisions scored in the day-6 flt-1-/- mutant vessels than in wild-type controls (see Movie S7 and the graph in Figure 5C). Each frame corresponds to a single exposure; exposures were taken at one-minute intervals.

A 216-minute time-lapse video of day-6 flt-1-/--eGFP differentiation culture that shows numerous flt-1-/- endothelial cells undergoing cell division. Note the increased number of endothelial cell divisions compared to wild-type (see Movie S6 and the graph in Figure 5C). Each frame corresponds to a single exposure; exposures were taken at one-minute intervals.