Abstract

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), a class III receptor tyrosine kinase, is expressed at high levels in the blasts of approximately 90% of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Internal tandem duplications (ITDs) in the juxtamembrane domain and point mutations in the kinase domain of FLT3 are found in approximately 37% of AML patients and are associated with a poor prognosis. We report here the development and characterization of a fully human anti-FLT3 neutralizing antibody (IMC-EB10) isolated from a human Fab phage display library. IMCEB10 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1], κ) binds with high affinity (KD = 158 pM) to soluble FLT3 in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and to FLT3 receptor expressed on the surfaces of human leukemia cell lines. IMC-EB10 blocks the binding of FLT3 ligand (FL) to soluble FLT3 in ELISA and competes with FL for binding to cell-surface FLT3 receptor. IMC-EB10 treatment inhibits FL-induced phosphorylation of FLT3 in EOL-1 and EM3 leukemia cells and FL-independent constitutive activation of ITD-mutant FLT3 in BaF3-ITD and MV4;11 cells. Activation of the downstream signaling proteins mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and AKT is also inhibited in these cell lines by antibody treatment. The antibody inhibits FL-stimulated proliferation of EOL-1 cells and ligand-independent proliferation of BaF3-ITD cells. In both EOL-1 xenograft and BaF3-ITD leukemia models, treatment with IMC-EB10 significantly prolongs the survival of leukemia-bearing mice. No overt toxicity is observed with IMC-EB10 treatment. Taken together, these data demonstrate that IMC-EB10 is a specific and potent inhibitor of wild-type and ITD-mutant FLT3 and that it deserves further study for targeted therapy of human AML. (Blood. 2004;104:1137-1144)

Introduction

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3)1-3 (for a review, see Lyman4 ) is a member of the class III receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family that also includes FMS, KIT, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF-R). These RTKs are characterized by an extracellular domain composed of 5 immunoglobulin-like motifs and by a cytoplasmic domain with a split tyrosine kinase motif. FLT3 is expressed in immature precursors of myeloid and B-lymphoid lineages.5,6 Interaction of FLT3 with its ligand, FLT3-L (FL), results in receptor dimerization, activation of the tyrosine kinase domain, and receptor autophosphorylation.7,8 Activated FLT3 transduces signals through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (Stat5), and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) pathways, among others.9-14

FLT3 also appears to play an important role in leukemia (reviewed in Gilliland and Griffin15 and Levis and Small16 ). FLT3 is overexpressed in approximately 90% of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), B precursor-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and a smaller fraction of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in blast crisis.17-19 FL stimulation of FLT3 promotes the proliferation and survival of leukemia blasts, and this can occur through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms.20-24 Mutations of the FLT3 receptor can also result in ligand-independent activation of its tyrosine kinase activity. Two types of activating mutations of FLT3 have been reported. Internal tandem duplication (ITD) of sequence within the juxtamembrane domain is found in up to 30% of patients with AML and is linked to a poor prognosis.25 Another 7% of AML patients have a point mutation, such as D835, within the FLT3 activation loop.26,27 Both mutations cause constitutive activation of its kinase domain and downstream signaling events and confer survival advantages to leukemia cells.13,14,26-28

Current treatments for AML are mostly unsuccessful.29 Although AML patients initially respond to induction therapy with cytosine arabinoside and anthracycline, cytotoxic therapy eventually fails because of disease relapse. The situation is even worse for elderly patients who are usually unable to tolerate aggressive treatment regimens such as dose-intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation.30 Therefore, novel forms of treatment for AML are needed to improve the cure rate and to lessen associated toxicities. Based on its role in leukemia, FLT3 is an attractive molecular target for leukemia therapy. To date, several FLT3-selective small molecule inhibitors have been reported.31-36 Most of these kinase inhibitors are active against FLT3 ITD. However, none of these inhibitors are truly FLT3 specific because they often recognize other molecular targets such as PDGF-R, KIT, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGF-R2). Because of their high specificity and high binding affinity, neutralizing antibodies offer an attractive approach for the development of FLT3 inhibitors. We report here the generation and characterization of a fully human anti-FLT3 neutralizing antibody and demonstrate that this antibody inhibits wild-type and ITD-mutant FLT3 in vitro. We also demonstrate that IMC-EB10 is effective in prolonging the survival of mice in 2 leukemia models expressing either wild-type FLT3 or FLT3 ITD.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male NOD-SCID mice and female athymic nude mice (NU/NU), 6 to 8 weeks of age, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), respectively, and housed under pathogen-free conditions.

Cell lines

Human leukemia cell lines JM1 (FLT3-negative), EOL-1, and EM3 (the latter 2 positive for wild-type FLT3) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C with 5% CO2.18 Human leukemia cell line MV4;11 (positive for FLT3 ITD) was maintained in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) supplemented with 20% FCS.32,37 The interleukin-3 (IL-3)-independent BaF3-ITD cell line was generated from BaF3 cells transformed with FLT3-ITD cDNA isolated from a patient with AML38 and was maintained in RPMI 1640 with 1 mg/mL geneticin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The BaF3-control cell line was generated by transfection of BaF3 cells with pCIneo vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and was maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% WEHI-conditioned medium.

Reagents

FLT3-Fc, a chimeric protein of the extracellular domain of human FLT3 fused to the 6 × histidine-tagged Fc region of human immunoglobulin G (IgG), was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Immunex (Seattle, WA) provided the recombinant human FL. A humanized anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody IMC-C225 (Cetuximab; ImClone Systems, New York, NY) was used as a control for in vitro experiments. Purified human IgG, purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA), was used as a control for in vivo experiments.

Selection of human anti-FLT3 Fab fragments from phage display library

The phage display procedure for selecting Fab fragments has been described previously.39 Briefly, a large human Fab phage display library containing 3.7 × 1010 clones was used for selection.40 The library stock was grown to log phase, rescued with M13K07 helper phage, and amplified overnight in 2YTAK medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 30°C. The phage preparation was precipitated in 4% PEG/0.5 M NaCl, resuspended in 3% fat-free milk/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1000 μg/mL Fc protein, and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour to capture phage displaying anti-Fc Fab fragments and to block nonspecific binding.

FLT3-Fc (50 μg/mL)-coated Maxisorp Star tubes (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were first blocked with 3% milk/PBS at 37°C for 1 hour and then incubated with the phage preparation at room temperature for 1 hour. Tubes were washed 10 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and then 10 times with PBS. Bound phage was eluted at room temperature (RT) for 10 minutes with 1 mL of 10 mM triethylamines (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The eluted phage was incubated with 10 mL mid log-phase TG1 cells at 37°C for 30 minutes stationary and 30 minutes shaking. Infected TG1 cells were pelleted and transferred to several large 2YTAG plates and incubated overnight at 30°C. All the colonies grown on the plates were scraped into 5 mL 2YTA medium, mixed with 10% glycerol, and stored in aliquots at -70°C. For the next round selection, 100 μL phage stock was added to 25 mL 2YTAG medium and grown to mid log-phase. The culture was rescued with M13K07 helper phage, amplified, precipitated, and used for selection following the procedure described above, with reduced concentrations (5 μg/mL) of FLT3-Fc immobilized on the immunotubes and increased numbers of washes after the binding process.

Individual TG1 clones were picked and grown at 37°C in 96-well plates and were rescued with M13K07 helper phage, as described above. The amplified phage preparation was blocked with 1/6 vol 18% milk/PBS at RT for 1 hour and was added to Maxisorp 96-well microplates (Nunc) coated with FLT3-Fc (1 μg/mL in 100 μL). After incubation at RT for 1 hour, the plates were washed 3 times with PBST and were incubated with a mouse anti-M13 phage antibody-horseradish peroxide (HRP) conjugate (Pharmacia Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Plates were washed 5 times, 3,3′, 5,5′-tetra-methylbenzidine (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) was added, and absorbance at 450 nm was measured in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Diversity of the anti-FLT3 Fab clones was determined by restriction analysis, and Fab purification was performed as previously described.39

Antibody engineering and expression

DNA sequences encoding heavy- and light-chain genes from Fab candidates were cloned into the glutamine synthetase expression system (Lonza Biologics, Portsmouth, NH). Stably transfected NS0 clones were cultured in serum-free condition, and IgG protein was purified by affinity chromatography. Purity of the antibody preparations was analyzed using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the concentrations were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with an antihuman Fc antibody as the capturing agent and an antihuman κ chain antibody-HRP conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory) as the detection agent. IMC-C225 was used as the standard for calibration. The endotoxin level of each antibody preparation was examined to ensure the products were free of endotoxin contamination.

ELISA binding and blocking assays

For the FLT3 binding assay, a 96-well plate (Nunc) was coated with an anti-His antibody (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) overnight at 4°C. Wells were blocked for 1 hour with blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween and 5% FCS) and then were incubated with FLT3-Fc (1 μg/mL × 100 μL/well) for 1 hour at room temperature. Wells were washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween, and IMC-EB10 or control IgG was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After washing, the plate was incubated with 100 μL antihuman κ chain antibody-HRP conjugate at room temperature for 1 hour. Plates were washed and incubated with 100 μL 3,3′, 5,5′-tetra-methylbenzidine. Absorbance at 450 nm was read on a microplate reader.

For the receptor-ligand blocking assay, varying amounts of IMC-EB10 or control IgG were mixed with a fixed amount of biotinylated FLT3-Fc fusion protein (45 ng/well) and were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The mixture was transferred to 96-well plates precoated with FL (25 ng/well) and incubated at room temperature for another 1 hour. After washing, streptavidin HRP conjugate was added, and the absorbance at 450 nm was read. The antibody concentration required for 50% inhibition of FLT3 binding to FL (IC50) was calculated.

Binding kinetics analysis of the antibody

Binding kinetics of the antibody to FLT3 was measured using a BiaCore 2000 biosensor (Pharmacia Biosensor, Uppsala, Sweden). Antibody was immobilized onto a sensor chip, and soluble FLT3-Fc fusion protein was injected at concentrations ranging from 1.5 to 100 nM. Sensorgrams were obtained at each concentration and evaluated using the BIA Evaluation 2.0 program to determine the association rate constant (kon) and the dissociation rate constant (koff). The dissociation constant KD was calculated from the ratio of rate constants kon/koff.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells (5 × 105) were washed twice in cold PBS and incubated for 30 minutes with 10 μg/mL anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) in 100 μL PBS to block Fc receptors on the cells. Cells were washed with cold PBS and then incubated for 45 minutes with IMC-EB10 (10 μg/mL) or corresponding human IgG isotype control diluted in PBS. Cells were washed with cold PBS and then incubated in 100 μL phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antihuman F(ab′)2 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) (1/200 dilution) for 45 minutes on ice. After washing, cells were analyzed using a Coulter Epics flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells were cultured in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium overnight. Cells were treated for 60 minutes with various concentrations of antibodies in serum-free medium. Cells were then stimulated with 30 ng/mL FL for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, and 1 μg/mL aprotinin). Equal amounts of cell lysates from each sample were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-FLT3 antibody 4G8 (BD PharMingen) and then with protein A agarose (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) for 2 more hours. After electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen), immunoblotting was performed with antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology) to assess phosphorylated FLT3. Membranes were stripped, treated with Qentix signal enhancer (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and reprobed with anti-FLT3 antibody S-18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) to detect total FLT3 protein. Protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). To detect activated MAPK, Stat5, or AKT, 50 μg cell protein extract was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies: phospho-p44/42 MAPK antibody, phospho-Stat5 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), or phospho-AKT antibody (BD PharMingen). To detect total MAPK, Stat5, or AKT proteins, membranes were stripped and reprobed with indicated antibodies: p44/42 MAPK antibody, Stat5 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), or AKT antibody (BD PharMingen).

Cell proliferation assays

EOL-1 cells were harvested and washed 3 times using serum-free RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were cultured in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium for 12 hours. Cells were reconstituted in serum-free AIM-V medium, plated in triplicate in a flat-bottomed, 96-well plate (1 × 104/100 μL/well), and incubated with varying concentrations of antibodies (0-100 nM) and 30 ng/mL FL at 37°C for 68 hours. As a background control, cells were incubated with medium alone in the absence of exogenous FL. Cells were then pulsed with 0.25 μCi/well (0.00925 MBq/well) of [3H]-thymidine for 4 hours. Cells were harvested, and cycles per minute were measured in a PerkinElmer Wallac-1205 Betaplate Liquid Scintillation Counter (Wellesley, MA). To calculate the percentage inhibition of FL-induced proliferation for EOL-1 cells, the cycles per minute of background proliferation (ie, cell samples not stimulated with FL) was first deduced from the cycles per minute of all experimental samples. The following formula was used: [(cpm of untreated sample - cpm of antibody-treated sample)/cpm of untreated sample] × 100%.

For BaF3-ITD cells, the proliferation assay was performed in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS in the absence of exogenous FL.

In vivo EOL-1 human xenograft and BaF3-ITD leukemia models

For the EOL-1 human xenograft leukemia model, NOD-SCID mice in groups of 10 were injected intravenously with 5 × 106 EOL-1 cells. Starting 1 day later, mice were treated 3 times weekly with intraperitoneal injections of 500 μg, 250 μg, 100 μg or 10 μg IMC-EB10 in 200 μL PBS solution. A control group was treated with purified human IgG (500 μg). Mice were monitored daily for survival.

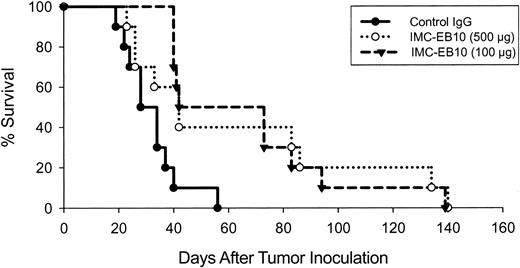

For the BaF3-ITD leukemia model, athymic nude mice in groups of 10 were injected intravenously with 5 × 104 BaF3-ITD cells. Starting 1 day later, mice were treated 3 times weekly with intraperitoneal injections of 500 μg or 100 μg IMC-EB10 or purified human IgG (500 μg). Mice were monitored daily for survival. For statistical analysis, the nonparametric 1-tailed Mann-Whitney rank sum test (SigmaStat 2.03; SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used.

Histology

Tissue samples were fixed overnight in 10% zinc formalin at 4°C, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm onto silane-coated slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemical staining of tumor cells, bone marrow cells were harvested from femurs of antibody-treated or untreated mice and captured on slides by dabbing. The slides were then incubated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antihuman CD45 antibody overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, slides were incubated with anti-FITC antibody-HRP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 30 minutes. Color was developed with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAKO, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom). Pictures were taken under a Zeiss Axioskop microscope with Ph2Plan-NeoPlurar lenses (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) at 0.17 numerical aperture using an AxioCam camera (Zeiss). Images were acquired using Axiovision 4.0 software (Zeiss).

Results

Binding and blocking activities of IMC-EB10

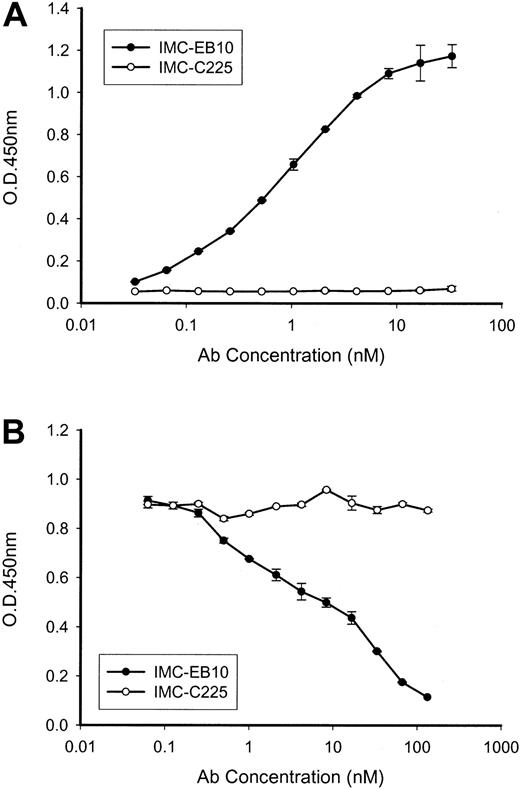

The human anti-FLT3 antibody IMC-EB10 (IgG1, κ) was constructed from a Fab fragment selected from a naive human-antibody, phage-display library through immunopanning against soluble FLT3-Fc protein. IMC-EB10 showed strong binding to soluble FLT3-Fc (Figure 1A). IMC-EB10 did not bind to a control fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-Fc fusion protein (data not shown), indicating its specificity for FLT3. IMC-EB10 did not cross-react with other tyrosine kinases, such as VEGF-R1, VEGF-R2, PDGFRa, and PDGF-Rb (data not shown). Binding kinetics of IMCEB10 to FLT3 was measured using BiaCore analysis (Pharmacia Biosensor). Affinity of IMC-EB10 (KD) was determined to be 158 pM, slightly higher than that reported for FL (200-500 pM).41 Association and dissociation rate constants (kon and koff) were 3.52 × 105 M-1 s-1 and 5.55 × 10-5 s-1, respectively. The ability of IMC-EB10 to block receptor-ligand binding was examined in an FL-binding competition ELISA. As shown in Figure 1B, IMC-EB10 blocked the binding of FL to FLT3 with an IC50 of 10 nM, whereas no blocking activity was seen for control IgG.

Binding and blocking activities of IMC-EB10. (A) Plates precoated with an anti-His antibody were incubated with His-tagged FLT3-Fc protein for 1 hour. After washing, titrated IMC-EB10 or control antibody IMC-C225 was added and incubated for 1 hour. Bound antibodies were measured in a biotin-streptavidin reaction with a microplate reader at OD450nm. IMC-EB10 is shown to bind to the FLT3 receptor in a dose-dependent manner. (B) Antibody competition assay of ligand-receptor binding was performed in plates coated with FL. Mixtures of biotinylated FLT3 receptor (fixed amount) and antibody (titrated concentrations) were then added and incubated for 1 hour. FLT3 receptor bound to FL was measured in a biotin-streptavidin reaction with a microplate reader at OD450nm. IMC-EB10 shows a strong blocking activity toward FL-FLT3 receptor binding. Error bars represent means ± SD.

Binding and blocking activities of IMC-EB10. (A) Plates precoated with an anti-His antibody were incubated with His-tagged FLT3-Fc protein for 1 hour. After washing, titrated IMC-EB10 or control antibody IMC-C225 was added and incubated for 1 hour. Bound antibodies were measured in a biotin-streptavidin reaction with a microplate reader at OD450nm. IMC-EB10 is shown to bind to the FLT3 receptor in a dose-dependent manner. (B) Antibody competition assay of ligand-receptor binding was performed in plates coated with FL. Mixtures of biotinylated FLT3 receptor (fixed amount) and antibody (titrated concentrations) were then added and incubated for 1 hour. FLT3 receptor bound to FL was measured in a biotin-streptavidin reaction with a microplate reader at OD450nm. IMC-EB10 shows a strong blocking activity toward FL-FLT3 receptor binding. Error bars represent means ± SD.

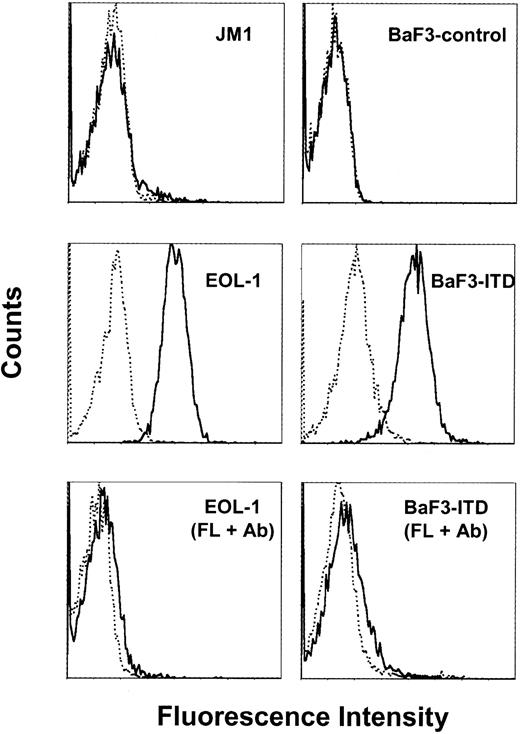

Whether IMC-EB10 recognizes cell-surface FLT3 was examined by flow-cytometric analysis. IMC-EB10 bound to wild-type FLT3 expressed on EOL-1 cells and also to ITD-mutant FLT3 expressed on BaF3-ITD cells. No binding for IMC-EB10 was observed on the FLT3-negative JM1 or the BaF3-control cell lines (Figure 2). Moreover, IMC-EB10 appears to share a common binding epitope with FL because binding to FLT3 was diminished when EOL-1 or BaF3-ITD cells were preincubated on ice for 30 minutes with FL before they were stained with the antibody (Figure 2).

IMC-EB10 binds to cell-surface FLT3 receptor in leukemia cells. Cells were incubated on ice with IMC-EB10 (solid line) or human IgG isotype control (dotted line) and then with PE-conjugated antihuman F(ab′)2 antibody. IMC-EB10 bound to the EOL-1 and BaF3-ITD cell lines, but not to the FLT3-negative cell lines JM1 or BaF3-control. Preincubation of EOL-1 or BaF3-ITD cells for 30 minutes on ice with FL (100 ng/mL) before antibody staining abrogated IMC-EB10 binding to cell surface FLT3 receptor.

IMC-EB10 binds to cell-surface FLT3 receptor in leukemia cells. Cells were incubated on ice with IMC-EB10 (solid line) or human IgG isotype control (dotted line) and then with PE-conjugated antihuman F(ab′)2 antibody. IMC-EB10 bound to the EOL-1 and BaF3-ITD cell lines, but not to the FLT3-negative cell lines JM1 or BaF3-control. Preincubation of EOL-1 or BaF3-ITD cells for 30 minutes on ice with FL (100 ng/mL) before antibody staining abrogated IMC-EB10 binding to cell surface FLT3 receptor.

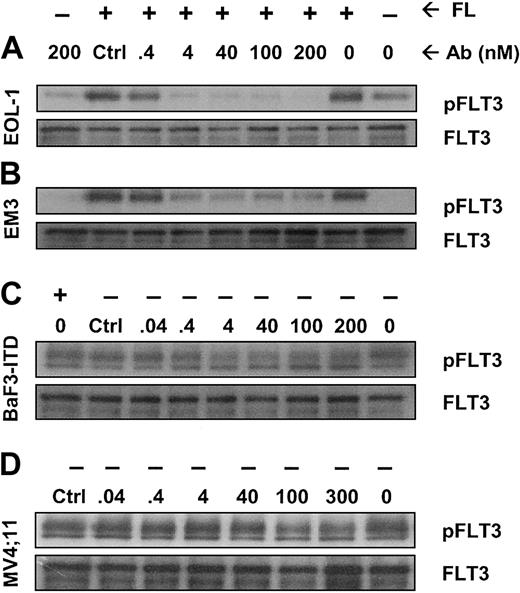

IMC-EB10 inhibits FL-induced phosphorylation of wild-type FLT3 and ligand-independent constitutive phosphorylation of ITD-mutant FLT3

We next investigated whether IMC-EB10 blockade of the FLT3-FL interaction would lead to the inhibition of FLT3 receptor phosphorylation in leukemia cells. In EOL-1 and EM3 cells, adding FL strongly increased FLT3 receptor phosphorylation. Incubation with IMC-EB10 blocked FL-induced phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 0.4 to 4 nM (Figure 3A-B). These results indicate that IMC-EB10 is a potent inhibitor of ligand-induced activation of wild-type FLT3.

IMC-EB10 inhibits FL-induced phosphorylation of wild-type FLT3 and ligand-independent constitutive phosphorylation of FLT3-ITD. (A) EOL-1 and (B) EM3 cells were incubated in varying concentrations of antibody in the presence or absence of FL (30 ng/mL). Lanes 1 and 2 (from right) indicate that a low level of FLT3 phosphorylation existed in untreated EOL-1 cells and that ligand strongly increased the level of receptor phosphorylation. Ligand-induced receptor phosphorylation was blocked by IMC-EB10 antibody but not by a control antibody (control, IMC-C225 at 200 nM). (C) BaF3-ITD and (D) MV4;11 cells were incubated in varying concentrations of antibody without exogenous FL. Ligand-independent phosphorylation was inhibited by IMC-EB10 treatment. Total FLT3 protein was unaffected by antibody treatment.

IMC-EB10 inhibits FL-induced phosphorylation of wild-type FLT3 and ligand-independent constitutive phosphorylation of FLT3-ITD. (A) EOL-1 and (B) EM3 cells were incubated in varying concentrations of antibody in the presence or absence of FL (30 ng/mL). Lanes 1 and 2 (from right) indicate that a low level of FLT3 phosphorylation existed in untreated EOL-1 cells and that ligand strongly increased the level of receptor phosphorylation. Ligand-induced receptor phosphorylation was blocked by IMC-EB10 antibody but not by a control antibody (control, IMC-C225 at 200 nM). (C) BaF3-ITD and (D) MV4;11 cells were incubated in varying concentrations of antibody without exogenous FL. Ligand-independent phosphorylation was inhibited by IMC-EB10 treatment. Total FLT3 protein was unaffected by antibody treatment.

The ITD mutation found with high frequency in AML is known to cause FL-independent receptor phosphorylation and activation of kinase signaling pathways. Using the BaF3-ITD and MV4;11 cell lines, we examined whether IMC-EB10 has an inhibitory effect on constitutive activation of mutant FLT3. As expected, the mutant FLT3 in BaF3-ITD and MV4;11 cell lines was constitutively phosphorylated. Compared with a control antibody, IMC-EB10 inhibited FL-independent FLT3-ITD phosphorylation in BaF3-ITD cells. To a lesser extent, IMC-EB10 also significantly inhibited FL-independent FLT3-ITD phosphorylation in MV4;11 cells (Figure 3C-D). Taken together, these results suggest that IMC-EB10 is also a potent inhibitor of FLT3-ITD kinase activity.

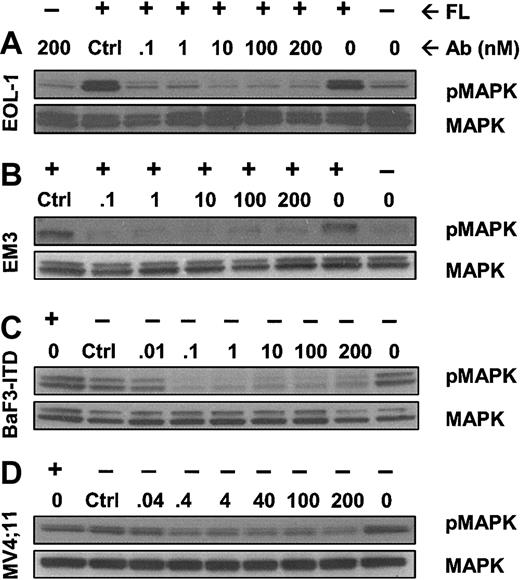

IMC-EB10 inhibits FLT3-mediated activation of downstream kinases

The MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and Stat5 pathways are involved in the downstream signaling of activated FLT3.9-14 To test the effect of IMC-EB10 on FLT3 signal transduction, we first examined the phosphorylation state of MAPK in FL-treated EOL-1 and EM3 cells in the presence of varying concentrations of the antibody. IMC-EB10 strongly blocked the phosphorylation of MAPK in both cell lines (Figure 4A-B). These results suggest that blocking the FLT3 ligand-receptor interaction by IMC-EB10 results in inhibition of the downstream MAPK signaling pathway. We next investigated the effect of IMC-EB10 on FL-independent MAPK phosphorylation induced by the FLT3-ITD mutation using the BaF3-ITD and MV4;11 cells. IMC-EB10 treatment blocked the constitutive phosphorylation of MAPK (Figure 4C-D).

IMC-EB10 inhibits phosphorylation of downstream MAP kinase induced by wild-type FLT3 or FLT3-ITD. (A) EOL-1 and (B) EM3 cells were incubated with varying amounts of antibody with or without exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). MAPK was phosphorylated after FL stimulation (lanes 1 and 2 from right). Control antibody treatment did not affect MAPK phosphorylation (lane 8 from right). In contrast, treatment with IMC-EB10 (1-200 nM) completely inhibited FL-induced MAPK phosphorylation. (C) BaF3-ITD and (D) MV4;11 cells were incubated in varying concentrations of antibody without exogenous FL. Lane 1 (from right) indicates that MAPK was constitutively phosphorylated. Treatment with control antibody did not affect ligand-independent constitutive MAPK phosphorylation (lane 8 from right). In contrast, constitutive MAPK phosphorylation was inhibited by IMCEB10. Total MAPK protein was unaffected by antibody treatment.

IMC-EB10 inhibits phosphorylation of downstream MAP kinase induced by wild-type FLT3 or FLT3-ITD. (A) EOL-1 and (B) EM3 cells were incubated with varying amounts of antibody with or without exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). MAPK was phosphorylated after FL stimulation (lanes 1 and 2 from right). Control antibody treatment did not affect MAPK phosphorylation (lane 8 from right). In contrast, treatment with IMC-EB10 (1-200 nM) completely inhibited FL-induced MAPK phosphorylation. (C) BaF3-ITD and (D) MV4;11 cells were incubated in varying concentrations of antibody without exogenous FL. Lane 1 (from right) indicates that MAPK was constitutively phosphorylated. Treatment with control antibody did not affect ligand-independent constitutive MAPK phosphorylation (lane 8 from right). In contrast, constitutive MAPK phosphorylation was inhibited by IMCEB10. Total MAPK protein was unaffected by antibody treatment.

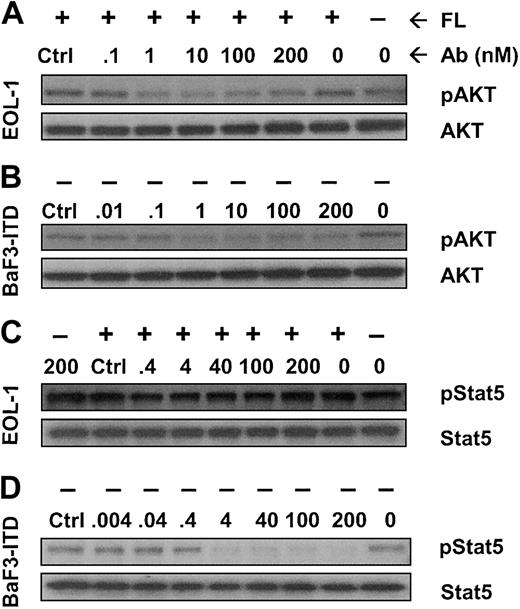

We also examined whether AKT and Stat5 signaling proteins were affected by IMC-EB10 inhibition of FLT3. Incubation with IMC-EB10 inhibited FL-induced phosphorylation of AKT in EOL-1 cells (Figure 5A) and the FL-independent phosphorylation of AKT in BaF3-ITD cells (Figure 5B). Interestingly, Stat5 was found to be activated in EOL-1 cells in the absence of FL stimulation. Incubation with IMC-EB10 did not have any significant effect on the activation state of Stat5 (Figure 5C). In BaF3-ITD cells, however, FL-independent Stat5 phosphorylation was strongly inhibited by IMC-EB10 (Figure 5D).

Effect of IMC-EB10 on the phosphorylation of AKT and Stat5. Cells were incubated with varying amounts of antibody with or without exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). (A) In EOL-1 cells, AKT phosphorylation was up-regulated after FL stimulation (lanes 1 and 2 from right). Control antibody treatment did not affect AKT phosphorylation (lane 8 from right). In contrast, IMC-EB10 treatment (1-200 nM) completely inhibited FL-induced AKT phosphorylation. (B) In BaF3-ITD cells, constitutive phosphorylation of AKT was strongly inhibited with IMC-EB10 treatment (1-200 nM). (C) In EOL-1 cells, Stat5 was phosphorylated in the absence of FL stimulation (lane 1 from right), and FL stimulation did not significantly increase the level of phosphorylation of Stat5. Incubation with IMC-EB10 did not have any significant effect on Stat5 phosphorylation in this cell line. (D) In BaF3-ITD cells, constitutive phosphorylation of Stat5 was strongly inhibited with IMC-EB10 treatment (4-200 nM). In both cell lines, total AKT or Stat5 proteins were unaffected by antibody treatment.

Effect of IMC-EB10 on the phosphorylation of AKT and Stat5. Cells were incubated with varying amounts of antibody with or without exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). (A) In EOL-1 cells, AKT phosphorylation was up-regulated after FL stimulation (lanes 1 and 2 from right). Control antibody treatment did not affect AKT phosphorylation (lane 8 from right). In contrast, IMC-EB10 treatment (1-200 nM) completely inhibited FL-induced AKT phosphorylation. (B) In BaF3-ITD cells, constitutive phosphorylation of AKT was strongly inhibited with IMC-EB10 treatment (1-200 nM). (C) In EOL-1 cells, Stat5 was phosphorylated in the absence of FL stimulation (lane 1 from right), and FL stimulation did not significantly increase the level of phosphorylation of Stat5. Incubation with IMC-EB10 did not have any significant effect on Stat5 phosphorylation in this cell line. (D) In BaF3-ITD cells, constitutive phosphorylation of Stat5 was strongly inhibited with IMC-EB10 treatment (4-200 nM). In both cell lines, total AKT or Stat5 proteins were unaffected by antibody treatment.

IMC-EB10 inhibits proliferation of leukemia cells expressing either wild-type or ITD-mutant FLT3

FL plays an important role in the proliferation of leukemia cells.20-24 Whether IMC-EB10 is capable of inhibiting FL-induced proliferation of these cells was investigated in a [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Incubation with FL (30 ng/mL) increased the [3H]-thymidine uptake of EOL-1 cells. Treatment with IMC-EB10 inhibited FL-induced proliferation of EOL-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6A).

IMC-EB10 inhibits proliferation of EOL-1 and BaF3-ITD cells. (A) EOL-1 cells were starved in serum-free medium overnight. Cells were resuspended in AIM-V medium and were incubated for 68 hours with varying concentrations of antibodies (0-100 nM) in the presence or absence of exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). In a background control, cells were incubated with medium alone in the absence of exogenous FL. Cell proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. For EOL-1 cells, background cycle per minute was deduced from the cycles per minute of all experimental samples. Percentage inhibition of FL-induced cellular proliferation was calculated as follows: [(cpm of untreated sample - cpm of antibody-treated sample)/cpm of untreated sample] × 100%. (B) Proliferation assay with BaF3-ITD cells was performed in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS in the absence of exogenous FL for all samples. Error bars represent means ± SD.

IMC-EB10 inhibits proliferation of EOL-1 and BaF3-ITD cells. (A) EOL-1 cells were starved in serum-free medium overnight. Cells were resuspended in AIM-V medium and were incubated for 68 hours with varying concentrations of antibodies (0-100 nM) in the presence or absence of exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). In a background control, cells were incubated with medium alone in the absence of exogenous FL. Cell proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. For EOL-1 cells, background cycle per minute was deduced from the cycles per minute of all experimental samples. Percentage inhibition of FL-induced cellular proliferation was calculated as follows: [(cpm of untreated sample - cpm of antibody-treated sample)/cpm of untreated sample] × 100%. (B) Proliferation assay with BaF3-ITD cells was performed in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS in the absence of exogenous FL for all samples. Error bars represent means ± SD.

As previously reported, FLT3-ITD-transformed BaF3 cells proliferate in the absence of FL stimulation.14 Indeed, we have found that FL stimulation did not increase the proliferation of BaF3-ITD cells. To investigate whether IMC-EB10 was able to inhibit the growth of leukemia cells expressing an FLT3-ITD mutation, proliferation assays were performed using BaF3-ITD cells in the absence of exogenous FL. IMC-EB10 treatment inhibited FL-independent proliferation of these cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6B).

In vivo efficacy of IMC-EB10 in animal models of leukemia expressing wild-type or ITD-mutant FLT3

To test the in vivo efficacy of the anti-FLT3 antibody, we intravenously inoculated NOD-SCID mice with EOL-1 cells and monitored the survival of mice treated intraperitoneally with various doses of IMCEB10 in comparison with control IgG-treated mice (Figure 7A). All mice in the control group succumbed to extensive dissemination of disease within 40 days (mean survival time, 36.0 ± 3.1 days). In comparison, survival was significantly prolonged in groups of mice treated with 500 μg, 250 μg, or 100 μg IMC-EB10 (mean survival times, 62.3 ± 18.7, 55.3 ± 18.9, or 52.8 ± 18.6, respectively; P < .001, P < .005, or P < .001, respectively). No effect was observed in the group treated with 10 μg IMC-EB10, indicating that the antileukemic effect of IMC-EB10 was dose dependent. In a separate experiment, bone marrow was harvested from IMC-EB10-treated mice (500 μg) and the control IgG-treated group at day 20 and was compared for the degree of tumor cell infiltration of bone marrow using immunohistochemical staining with an antihuman CD45 antibody. The number of tumor cells in bone marrow was decreased significantly in IMC-EB10-treated mice (Figure 7B).

In vivo therapeutic effect of IMC-EB10 in EOL-1 xenograft leukemia model. (A) NOD-SCID mice (10 per group) bearing EOL-1 leukemia were treated intraperitoneally with indicated doses of antibodies 3 times weekly. Mouse survival was monitored daily. Compared with control IgG, treatment with 500 μg, 250 μg, and 100 μg IMC-EB10 all significantly prolonged survival of the mice. No effect was seen for 10 μg IMC-EB10, suggesting that the antileukemic effect of IMC-EB10 was dose dependent. This graph is representative of results from 3 similar experiments. (B) Mice bearing EOL-1 leukemia were treated with IMC-EB10 (500 μg) for 20 days. Mice were killed, and bone marrow cells were analyzed by immunohistochemical staining with antihuman CD45 antibody. The number of leukemia cells was significantly decreased by IMC-EB10 treatment. Original magnification, × 200.

In vivo therapeutic effect of IMC-EB10 in EOL-1 xenograft leukemia model. (A) NOD-SCID mice (10 per group) bearing EOL-1 leukemia were treated intraperitoneally with indicated doses of antibodies 3 times weekly. Mouse survival was monitored daily. Compared with control IgG, treatment with 500 μg, 250 μg, and 100 μg IMC-EB10 all significantly prolonged survival of the mice. No effect was seen for 10 μg IMC-EB10, suggesting that the antileukemic effect of IMC-EB10 was dose dependent. This graph is representative of results from 3 similar experiments. (B) Mice bearing EOL-1 leukemia were treated with IMC-EB10 (500 μg) for 20 days. Mice were killed, and bone marrow cells were analyzed by immunohistochemical staining with antihuman CD45 antibody. The number of leukemia cells was significantly decreased by IMC-EB10 treatment. Original magnification, × 200.

Because IMC-EB10 showed a significant antiproliferative effect on BaF3-ITD cells in vitro, we tested whether the antibody could also affect the growth of this mutant FLT3 leukemia model in vivo. Nude mice were inoculated intravenously with BaF3-ITD cells and then treated intraperitoneally with IMC-EB10 (500 μg or 100 μg) or control human IgG (Figure 8). In comparison with control IgG treatment (mean survival time, 32.2 ± 10.7 days), IMC-EB10 treatment significantly prolonged the survival of mice (63.4 ± 44.6 days, P < .05 for the 500-μg dose; 66.5 ± 32.9 days, P < .01 for the 100-μg dose). These results suggest that IMCEB10 is therapeutically effective in wild-type FLT3 and ITD-mutant FLT3 models in vivo.

In vivo therapeutic effect of IMC-EB10 in BaF3-ITD leukemia model. Athymic nude mice (10 per group) with BaF3-ITD leukemia were treated intraperitoneally with indicated doses of antibodies 3 times weekly. Mouse survival was monitored daily. Compared with control IgG, treatment with IMC-EB10 (500 μg and 100 μg) significantly prolonged survival of the mice.

In vivo therapeutic effect of IMC-EB10 in BaF3-ITD leukemia model. Athymic nude mice (10 per group) with BaF3-ITD leukemia were treated intraperitoneally with indicated doses of antibodies 3 times weekly. Mouse survival was monitored daily. Compared with control IgG, treatment with IMC-EB10 (500 μg and 100 μg) significantly prolonged survival of the mice.

Given that IMC-EB10 cross-reacts with mouse Flt3 and blocks mouse Flt3 ligand binding to mFlt3 (data not shown), an experiment was performed to investigate whether IMC-EB10 might have any toxic effect on mice. Naive NOD-SCID mice were treated intraperitoneally with the antibody (1 mg, 3 times weekly) for 3 months and were monitored for any sign of adverse effects. No weight loss or any sign of sickness was observed in these mice compared with PBS-treated mice. The number of granulocytes in the peripheral blood was unchanged. Histologic analysis revealed no abnormal changes in bone marrow, brain tissue, spleen, kidney, lung, or heart (data not shown).

Discussion

We have developed a high-affinity, fully human, anti-FLT3 neutralizing antibody and tested this antibody for its ability to inhibit the function of FLT3 in leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Antibody IMC-EB10 binds to FLT3 receptor expressed on the surfaces of human leukemia cell lines and blocks the binding of FL to FLT3 receptor. We have demonstrated that IMC-EB10 not only blocks FL-induced phosphorylation of FLT3 but also inhibits ligand-independent phosphorylation of ITD-mutant FLT3. MAPK and AKT, downstream signaling targets of FLT3, are inhibited in response to IMC-EB10 treatment. We have also shown that IMC-EB10 inhibits FL-stimulated proliferation of EOL-1 cells and ligand-independent growth of BaF3-ITD cells. In vivo efficacy of the antibody was investigated in a human xenograft EOL-1 leukemia model and a BaF3-ITD leukemia model. Treatment with the antibody significantly prolonged the survival of leukemia-bearing mice in both cases. Taken together, these data suggest that IMC-EB10 is a potent inhibitor of wild-type FLT3 and FLT3 ITD in vitro and in vivo.

The important role of FLT3 in the survival and proliferation of leukemia cells and its overexpression and mutation in high percentages of AML and ALL patients make FLT3 an attractive target for leukemia therapy. To date, several FLT3-selective, small-molecule inhibitors have been reported.31-36 Indolocarbazole derivative CEP-701 is a potent and selective inhibitor of FLT3 phosphorylation in FLT3-ITD-expressing BaF3 cells, human AML cell lines, and primary AML cells in vitro, and it prolongs mouse survival in an in vivo leukemia model.32 It is undergoing testing in patients with relapsed and refractory AML with FLT3-activating mutations. N-benzoylstaurosporine (PKC412), originally developed as a protein kinase C inhibitor, is a potent inhibitor of ITD-mutant FLT3 tyrosine kinase activity and is now being tested as an antileukemia agent in patients with mutant FLT3 receptors.33 Another compound, CT53518, is an antagonist of FLT3, PDGF-R and KIT, and has shown efficacy in FLT3-ITD-positive leukemia models in vivo.34 SU11248, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting VEGF-R2 and PDGF-R, was also found to inhibit FLT3 tyrosine kinase activity in vitro and in leukemia models in vivo.36 Most of these kinase inhibitors are not truly FLT3 specific because they also target other kinases, such as high-affinity nerve growth factor receptors,32 protein kinase C,33 VEGF-R2, PDGF-R, and KIT.34-36 Their broad target profiles make accurate evaluation of the role of inhibiting FLT3 kinase activity in the treatment of this disease difficult based on results obtained with these compounds. Potential toxicity could also be a major concern because these kinase inhibitors have multiple targets. It is unclear whether any of these compounds alone can achieve levels high enough to significantly inhibit FLT3. Moreover, several of these compounds inhibit FLT3-ITD better than wild-type FLT3. It is not yet clear whether these compounds can be effective against leukemia associated with the overexpression of wild-type FLT3. Resistance to small-molecule FLT3 inhibitors is also likely to arise, as has been seen for imatinib mesylate in CML. An FLT3-specific antibody may overcome some of these shortcomings. Our results with IMC-EB10 demonstrate that inhibiting FLT3 function with a neutralizing antibody may prove a viable approach to AML therapy. Further validation of this approach requires additional studies in models of primary leukemia.

The present study has demonstrated that IMC-EB10 has an inhibitory effect not only on wild-type FLT3 but also on ITD-mutant FLT3. However, the mechanisms underlying the ability of IMC-EB10 to inhibit FLT3-ITD remain to be clarified. One possible mechanism is antibody-mediated internalization and down-modulation of cell-surface FLT3 receptor. In a preliminary experiment, we found that the FLT3 receptor was internalized on incubation with IMC-EB10 antibody for 1 to 6 hours (see Supplemental Materials on the Blood website; click on the Data Set link at the top of the online article), supporting such a possibility. On the other hand, it has been hypothesized that disrupting an autoinhibitory motif in the juxtamembrane domain, either by deletion or insertion, results in constitutive activation of the FLT3 kinase.42 This model may offer another potential mechanism for the antibody-mediated inhibition of FLT3-ITD activity. The antibody binding to the FL binding site in the FLT3-ITD dimer could potentially induce a conformational change of its tertiary structure, resulting in re-exposure of the autoinhibitory motif and ultimately in deactivation of its kinase activity. Clearly, additional studies are required to elucidate the precise mechanism(s) of IMC-EB10 inhibition of FLT3-ITD activity.

EOL-1 cells have recently been reported to express the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene.43 In fact, Stat5 and, to a lesser extent, MAPK and AKT are phosphorylated in EOL-1 cells even in the absence of FL stimulation. Interestingly, we found that activation of MAPK and AKT, but not of Stat5, can be blocked by IMC-EB10 inhibition of FL-stimulated FLT3 activation in EOL-1 cells. By contrast, in BaF3-ITD cells, which do not express FIP1L1-PDGFRA, activation of all 3 downstream signaling targets (MAPK, AKT, and Stat5) can be blocked as a result of FLT3 inhibition. These data suggest that FIP1L1-PDGFRA may contribute to the state of Stat5 observed in EOL-1 cells.

There are 2 forms of FLT3, the high-molecular-weight glycoprotein at the plasma membrane and the low-molecular-weight glycoprotein in the endoplasmic reticulum.44 It appears that both forms of FLT3 are phosphorylated in ITD-mutant cell lines BaF3-ITD and MV4;11. In wild-type, FLT3-expressing EOL-1 and EM3 cell lines, only the high-molecular-weight form of FLT3 was strongly activated on FL stimulation. A similar pattern of expression is shown in some previously published papers.32,34 In the case of BaF3-ITD and MV4;11 cells, it appears that the plasma membrane p-FLT3, but not the cytoplasmic p-FLT3, was significantly affected by IMC-EB10 treatment. This observation suggests that the cytoplasmic form of the receptor is less accessible to an antibody inhibitor than the plasma membrane form of the receptor. This may partially explain why it is apparently difficult to achieve cell death with the antibody and why disease latency was prolonged but not cured in our in vivo leukemia models. Notably, several small-molecule FLT3 inhibitors appear to be able to inhibit both forms of phosphorylated FLT3 in FLT3-ITD-positive cells in vitro.32,35 Such differential effects on cell surface and cytoplasmic forms of a receptor by small-molecule compared with antibody antagonists have been previously reported for VEGF-R1 inhibitors.45

The FLT3 receptor is expressed in immature precursor cells of myeloid and B-cell lineages. Targeted disruption of the FLT3 gene results in healthy adult mice with normal, mature hematopoietic populations, but they have subtle deficiencies of primitive B-lymphoid progenitors, NK cells, and hematopoietic stem cells.6 Therefore, the potential toxicity of FLT3-based therapies might be similar to the cellular deficiencies noted in the FLT3 knockout mice. We carefully examined the adverse effects associated with IMC-EB10 treatment. First, no overt toxicities, such as weight loss, were observed. Second, in a treatment experiment with normal mice, we did not find morphologic or microscopic changes in any organs examined. Hematologic profiles remained unchanged in these mice. These results suggest a safe toxicity profile for the FLT3-specific antibody, though whether this treatment affects primitive precursor cell populations must be further investigated.

In summary, our data suggest that FLT3-specific antibodies may be useful not only in treating leukemia patients with FLT3-ITD mutations but also in treating those with associated overexpression of the wild-type FLT3 allele. IMC-EB10, as an efficacious and apparently nontoxic FLT3 inhibitor, may be a candidate for clinical testing in AML patients, especially those for whom cytotoxic chemotherapy has failed or those who are too old for more intensive treatment regimens, such as bone marrow transplantation. Moreover, anti-FLT3 antibody-based therapy may have synergistic effects when combined with other therapies, such as cytotoxic chemotherapy46 and antiangiogenic therapy.47,48 Further experiments to optimize anti-FLT3 antibody-based treatments are clearly warranted and might ultimately improve outcomes for patients with AML and other types of leukemia.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 22, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2585.

Some of the authors (Y.L., H.L., M.-N. W., D.L., R.B., Y.W., H.Z., P.B., D.L.L., B.P., P.K., P.B., L.W., Z.Z., and D.J.H.) are employed by a company (ImClone Systems) whose potential product was studied in the present work.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr D. Pereira for helpful suggestions; X. Jimenez for BiaCore analysis; H. Koo, A. Persaud, A. Kayas, and V. Mangalampalli for antibody expression; M. J. Kim, R. Apblett, and A. Malikzay for antibody purification; and G. Makhoul for assistance with histologic analysis.

![Figure 6. IMC-EB10 inhibits proliferation of EOL-1 and BaF3-ITD cells. (A) EOL-1 cells were starved in serum-free medium overnight. Cells were resuspended in AIM-V medium and were incubated for 68 hours with varying concentrations of antibodies (0-100 nM) in the presence or absence of exogenous FL (30 ng/mL). In a background control, cells were incubated with medium alone in the absence of exogenous FL. Cell proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. For EOL-1 cells, background cycle per minute was deduced from the cycles per minute of all experimental samples. Percentage inhibition of FL-induced cellular proliferation was calculated as follows: [(cpm of untreated sample - cpm of antibody-treated sample)/cpm of untreated sample] × 100%. (B) Proliferation assay with BaF3-ITD cells was performed in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS in the absence of exogenous FL for all samples. Error bars represent means ± SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/4/10.1182_blood-2003-07-2585/6/m_zh80160465320006.jpeg?Expires=1765023668&Signature=fpNfq8HpVys63rrQT68x1X61bDxIQ~xqZsLV9vTIOwvQbH6OiTmCl-StS9crvqcFqzXFsRb4yekP7mOChzqNQZFzO3KD4uhtAE~eN5fBYhtXgmij8jRirnsqheysogjeVut0--A5fnXZGQLvc5tFaqpX4SZz6A09QA9f5STNRAg7DaYreooBspQR07iAlhe4vX4Zeq5G9IKZQ53pw63vldxYqslC9DQg9cVQmMmoiWdDqxQFHIME05SE40ph2bZTbv4GTLeONKTbWB6KNQ~YriMZ0nrR~7R3hYtLV2ncR~kKBQJXSWnI47U7ZUndle-nLfnDTV0Bz4Wv-PZMBLwktA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)