Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell alloreactivity is reported to mediate strong GvL (graft versus leukemia) effect in patients after haploidentical stem-cell transplantation (SCT) for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Because subsequent immune reconstitution remains a major concern, we studied NK-cell recovery in 10 patients with AML who received haplomismatched SC transplants, among whom no GvL effect was observed, despite the mismatched immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) ligand in the GvH direction for 8 of 10 patients. NK cells generated after SCT exhibited an immature phenotype: the cytotoxic CD3-CD56dim subset was small, expression of KIRs and NKp30 was reduced, while CD94/NKG2A expression was increased. This phenotype was associated to in vitro lower levels of cytotoxicity against a K562 cell line and against primary mismatched AML blasts than donor samples. This impaired lysis was correlated with CD94/NKG2A expression in NK cells. Blockading CD94/NKG2A restored lysis against the AML blasts, which all expressed HLA-E, the ligand for CD94/NKG2A. Our present study allows a better understanding of the NK-cell differentiation after SCT. These results revealed that the NK cells generated after haplomismatched SCT are blocked at an immature state characterized by specific phenotypic features and impaired functioning, having potential impact for immune responsiveness and transplantation outcome.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK)-cell lysis is negatively regulated by inhibitory immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on target cells. When the necessary additional activating signals are present, NK cells lyse target cells that lack specific KIR ligands.1,2 KIR receptors are clonally distributed on NK cells,3 and KIR-bearing NK cells make up a discrete repertoire in any individual. Consequently, NK cells will be alloreactive toward cells that lack their KIR ligands and conversely tolerant to self-antigens.4 The inactivation of NK cells by self-HLA molecules may be a mechanism that permits malignant host cells to evade NK-cell-mediated immunity and may explain in part why adoptively transfused autologous NK cells or lymphokine-activated killer cells only mediate partial antitumoral effects.5 It has previously been reported that allogeneic NK cells can mediate antileukemic effects against high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after allogeneic haploidentical6,7 and partially mismatched unrelated8 hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (SCT) with KIR ligand/KIR ligand incompatibility in the graft-versus-host (GvH) direction; that is, when an MHC class I KIR ligand is absent in the recipient but present in the donor. In this situation, ligands expressed on recipient leukemia cells do not inhibit donor NK-cell cytotoxicity, which, in turn, substantially reduces the risk of disease relapse (compared with patients whose transplantation lacked such a mismatch). Furthermore, haploidentical SCT is an interesting alternative when no sibling or unrelated HLA-matched donor is available. Transplantation across the histocompatibility barrier is now possible, when extensive T depletion of the graft to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) is combined with a very immunosuppressive-conditioning regimen and high doses of hematopoietic CD34+ cells to overcome host-versus-graft (HvG) reaction.9-11

After SCT with purified CD34+ cells, the distinct cell lineages of the developing immune system reconstitute at very different rates. T-cell recovery is very slow, but new NK cells integrate this system within 2 to 3 weeks by rapid differentiation from engrafted CD34+ cells.12-14 This maturation occurs under the influence of the microenvironment and the KIR epitopes expressed on the donor hematopoietic cells and host marrow stromal cells.15-17 In healthy individuals, mature NK cells comprise roughly 10% of circulating lymphocytes and are important effectors of innate immunity because they can lyse target cells without prior antigen stimulation.18 They are a heterogeneous population made up of different subsets with distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics, including a predominant highly cytotoxic CD3-CD56dim subset and a relatively small population of CD3-CD56bright cells that produce abundant cytokines but are only slightly cytotoxic.19,20 The heterogeneity of NK cells, that is, the diversity of the repertoire and their functional differences, is likely to affect immune response after hematopoietic SCT, that is, the success of engraftment, tolerance to alloantigens, and recognition and eradication of malignant tumor cells.

Patients undergoing haplo-SCT provide a unique model for analyzing NK-cell differentiation in vivo, because the circulating NK cells that appear at engraftment are probably generated directly from the CD34+ graft and are minimally contaminated by the mature NK cells present in it. No study has examined the maturation state of NK cells after haploidentical SCT in adult recipients, even though these cells are thought to carry out the major portion of the graft-versus-leukemia (GvL) effect in this situation. The aim of this study was to analyze the reconstitution of the NK compartment during the first 4 months after haploidentical SCT in adults receiving this transplant for malignant hematopoietic disease. We analyzed the postgraft phenotypic expression of natural toxicity receptor (NCR), KIRs, and CD94/NKG2A on NK cells as well as their cytolytic functioning against the recipient leukemic blasts. Our study revealed that phenotypic and functional abnormalities accompanied the rapid recovery of circulating NK cells. We consider the question of the correlation of the immature state of NK cells with the clinical outcome observed after haploidentical SCT in our experience.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and donors

Ten young adult (median age, 24 years; range, 15-38 years) patients received a hematopoietic SC transplant from fully haplomismatched related donors at Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital, France, between March 1997 and September 2003. The indication for all transplantations was high-risk (refractory to chemotherapy or in second or third remission) AML and no available matched donor. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of patients. Patients received a positive selection of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized peripheral stem-cell CD34+ cells obtained with Miltenyi beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), to ensure extensive T-cell depletion (< 1 × 105/kg). Eight of the 10 patients received grafts with a KIR ligand incompatibility in the GvH direction (Table 2), as defined by Ruggeri et al.6

The following receptors and their ligands were taken into consideration in the analysis: KIR2DL1 (CD158.a) is specific for group 2 HLA-C allotypes with lysine at position 80 (Cw2, 4, 5, 6, 15, 17, 18, and related alleles); KIR2DL2 (CD158.b) is specific for group 1 HLA-C allotypes with asparagine at position 80 (Cw1, 3, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, and related alleles), and KIR3DL1 (CD158.e) is specific for HLA-B allotypes expressing the serologic epitope Bw4. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses and cytotoxic assays were performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from the last 6 patients (patients no. 5 to no. 10), engrafted between November 2002 and September 2003, and all were mismatched in the GvH direction. Patients and donors provided informed consent in compliance with the ethics committee guidelines before peripheral blood samples were collected for the study.

HLA typing

HLA-A and -B were serologically determined. HLA-C type was determined by polymerase chain reaction sequence-specific oligonucleotides (PCR-SSO) using the INNO-LiPA kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL).

Transplantation procedure

Patients underwent the conditioning regimen described by Ruggeri et al6 and Aversa et al9 , which combined total body irradiation (TBI) with subsequent anti-T-cell globulin, fludarabine, and thiotepa. They received no immunosuppression drug treatment after engraftment as GvHD prophylaxis. Supportive care was provided as previously described.9

Flow cytometry (FACS)

Cell-surface staining that used a 4-color FACS analysis was performed on freshly harvested blood cells. Isotype-matched immunoglobulin served as the negative control (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). NK cells were analyzed after staining with an appropriate antibody cocktail: anti-CD45 (HI30), anti-CD3 (UCHT1; BD Biosciences Pharmingen), anti-CD56 (NKH1; Beckman-Coulter, Marseille, France), anti-KIR2DL1/CD158a (HP-3E4), anti-KIR2DL2/CD158b (CH-L), anti-KIR3DL1/CD158e/NKB1 (DX9), anti-2B4 (2-69), anti-CD16 (3G8; BD), anti-NKG2A/CD159a (Z199), anti-NKp30 (Z25), anti-NKp44 (Z231), and anti-NKp46 (BAB281; Beckman-Coulter). Leukemic blast cells were studied with the following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): anti-CD45 (HI30)-APC (allophycocyanin), anti-HLA-A, -B, -C-FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate), anti-CD11a/LFA1 (G4325B)-PE (phycoerythrin; BD Biosciences). Myeloid blasts cells were identified by their low expression of CD45. Erythrocytes were lysed with the FACS lysing solution kit (BD). After extensive washing, at least 20 000 events were analyzed on a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Results were analyzed with CellQuest software (BD) and expressed as the percentage of mAb-positive CD45+ or CD3-CD56+ cells in the mononuclear cell gate.

Western blot analysis of HLA-E on leukemic blasts

HLA-E expression by AML leukemic blasts from 5 patients was analyzed by Western blot, as previously described.21 Briefly, whole-cell lysate was prepared with the M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Pierce) and kept on ice for 1 hour. Protein concentration after centrifugation was determined with the BCA-200 protein assay kit (Pierce). Lysate (10 mg) was electrophoresed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane filter. Immunoblotting used a 1:10 000 dilution of the anti-HLA-E (MEM-E/02; Exbio, Prague, Czech Republic) mAb, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoblot was developed with a Western blotting detection system (Pierce).

NK-cell preparation and cytolytic assay

PBMCs were collected from the donors and from patients at engraftment and monthly thereafter. NK cells were isolated by depletion of T, B, and myeloid cells (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergish Gladbach, Germany; purity > 95%) and were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in the presence of 100 IU/mL interleukin 2 (IL-2; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 48 hours.

NK-cell cytotoxicity against both MHC class I-deficient human erythro-leukemia K562 cell line and primary leukemic blasts from patients was evaluated in a standard 4-hour 51Cr release assay, as previously described.22 The inhibitory effect of HLA-E expression on target cells was tested with the MHC class I-deficient 721-221 human cell line and transfected LCL-221-AEH cells, which express the E*0101 allele, as previously described23,24 (generously provided by D. Geraghty, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). The role of CD94/NKG2A was analyzed by adding an anti-NKG2A (Z199) mAb (Immunotech, Marseille, France) or its immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b) isotypic control (BD), at a final concentration of 20 μg/mL and incubating them with the effector cells for 30 minutes at 37°C.

Results

Clinical outcome

Outcome was very poor: no patient survived to 11 months after SCT. Relapse caused 7 of the 10 deaths: all occurred in the early posttransplantation period (median time of relapse, day 115; range, day 59-185). One of these patients died of infection on day 31 after the transplantation, and the remaining 2 died of treatment toxicity at 7 and 4 months after SCT (Table 1). No GvH or HvG reaction was observed.

NK-cell reconstitution after haploidentical SCT

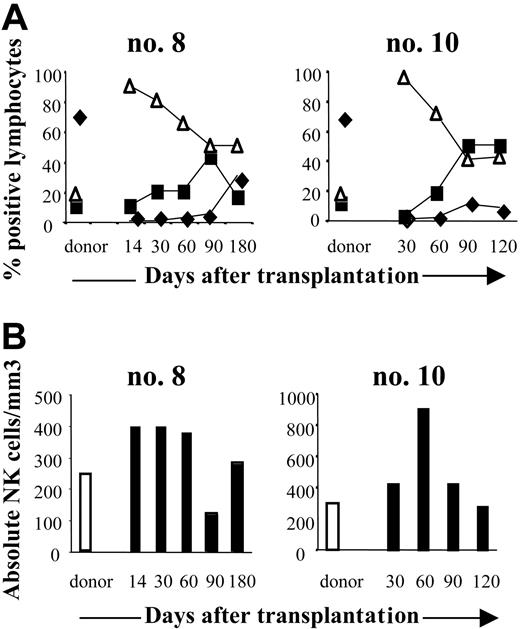

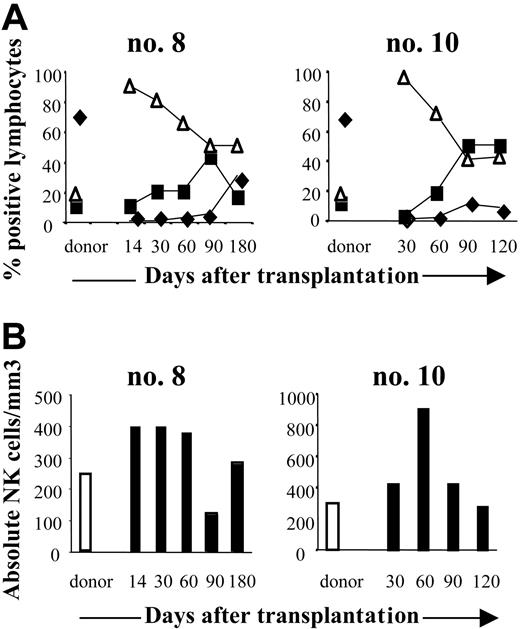

To monitor NK-cell recovery after transplantation, FACS analysis measured the number and frequency of CD3-CD56+ cells. NK cells were detectable in all 6 patients soon after transplantation: at engraftment their NK counts (324 ± 185/mm3; range 78-589/mm3 at 1 month after transplantation and 287 ± 171/mm3; range, 140-550/mm3, at 3 months), had reached those of the donors (310 ± 125/mm3; range, 233-456/mm3) (Figure 1A). At each sampling point, CD3-CD56+ NK cells accounted for most of the circulating lymphocyte population: 89% ± 7% of the lymphocytes at 1 month (range, 80%-98%), and 59% ± 16% at 3 months (range, 40%-86%) (Figure 1A). In contrast, CD3+ T cells reconstituted later and were usually not detectable until the fourth month after graft. At 1 month after SCT, the mean absolute T-cell count was 0.4 ± 0.8/mm3 (range, 0-2/mm3) and 192 ± 392/mm3 (range, 0-990/mm3) at 3 months (Figure 1B). Of the 6 patients monitored, none had regained a normal T-lymphocyte count by the last assessment (6 months after SCT).

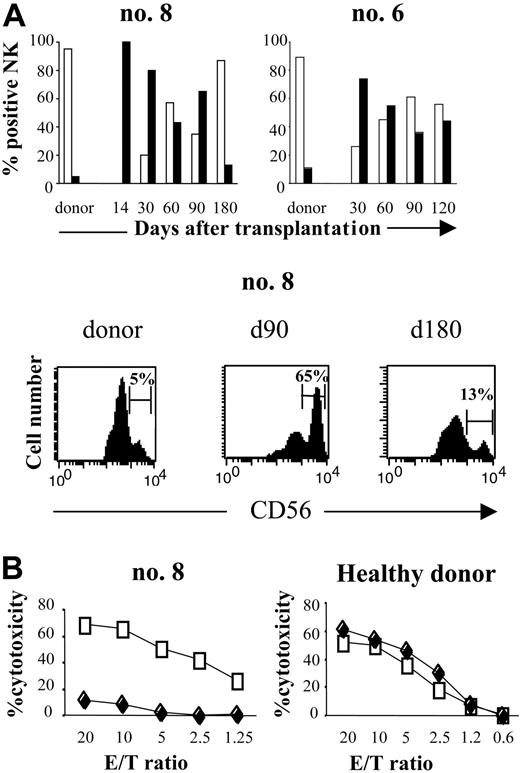

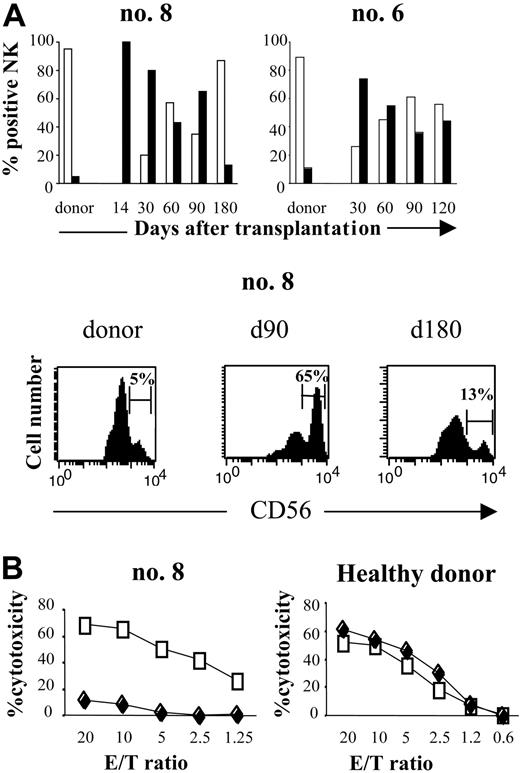

Phenotypic analysis defined the differentiation stage of CD3-CD56+ cells and thereby characterized the NK-cell population generated after SCT. CD3-CD56bright NK cells represented a very small fraction of the total circulating NK-cell population in donors (5% ± 2.7%; range, 3%-11%). In contrast, this NK subset was sharply higher in recipients, both as a percentage and an absolute count, especially during the first 3 months (Figure 2A).

It represented 47% ± 27% of the total NK cells at 1 month (range, 22%-80%) and 38% ± 20% at 3 months (range, 14%-65%). Most remarkably, there were many fewer CD3-CD56dimNK cells than in normal peripheral blood, where they are usually the predominant subset of mature cytotoxic NK cells. Thus, despite the rapid numerical recovery of CD3-CD56+ cells, their phenotypic profile reflects abnormalities in NK-cell differentiation after SCT.

To examine the functional effects of this increase in the CD3-CD56bright subset during early recovery after SCT, we compared the cytotoxicity of NK cells at engraftment (day 14) with that of NK cells from the same patient isolated 6 days later (day 20). The percentage of CD56dim cells in those samples was nearly 0% and 20%, respectively. As Figure 2B shows, the killing potential of the NK cells against K562 cells at engraftment was much lower than that of the NK cells isolated 6 days later. As control, we performed the same experiments with NK cells isolated from unrelated healthy donors. NK cells were stimulated 2 days and 8 days with IL-2 100 IU/mL and tested against K562. Cytotoxicity of healthy donors NK cells against K562 was similar after 2 days or 8 days of activation (Figure 2B). Taken together, these results suggest that the reduced fraction of the highly cytotoxic CD56dim NK-cell subset during the first months after engraftment was correlated with diminished cytotoxicity.

Reconstitution of NK cells after haploidentical SCT. (A) FACS analysis of CD3+, CD19+, and CD3-CD56+ cells in peripheral blood (PB) from 2 donor and patient pairs (no. 8, no. 10). PB from donors was collected before SCT and from patients at engraftment to the fourth or sixth month after SCT. Cells were analyzed on lymphocyte gates. T (♦), B (▪), and NK (▵) cell contents are expressed as a percentage of CD45+ lymphocytes. (B) Absolute counts of CD3-CD56+ NK cells in PB of the same pairs. Days after transplantation are indicated.

Reconstitution of NK cells after haploidentical SCT. (A) FACS analysis of CD3+, CD19+, and CD3-CD56+ cells in peripheral blood (PB) from 2 donor and patient pairs (no. 8, no. 10). PB from donors was collected before SCT and from patients at engraftment to the fourth or sixth month after SCT. Cells were analyzed on lymphocyte gates. T (♦), B (▪), and NK (▵) cell contents are expressed as a percentage of CD45+ lymphocytes. (B) Absolute counts of CD3-CD56+ NK cells in PB of the same pairs. Days after transplantation are indicated.

Distribution of CD56dimand CD56brightNK cells subsets after haploidentical SCT. (A, top) FACS profile of CD3-CD56dim (□) and CD3-CD56bright (▪) subpopulations of CD3-CD56+ NK cells in 2 patients after haploidentical SCT (no. 8, no. 6), compared with their respective donors. Percentage of NK cells is presented from the engraftment (day 14) to the sixth or fourth month after SCT. Days after transplantation are indicated. (Bottom) Flow cytometric density plots are gated on CD3-CD56+ NK cells at 90 and 180 days after transplantation and are compared with donors. Percentage of CD3-CD56dim and CD3-CD56bright cells in the total CD3-CD56+ population are indicated. (B, left) Cytotoxicity of CD3-CD56bright NK cells compared with CD56dim NK cells against K562 target cells, for patient no. 8. At engraftment (day 14), all NK cells were CD56bright (♦). These cells were collected and then activated by 100 IU/mL IL-2 for 8 days. At day 20, PB from the same patient was collected: 80% of circulating NK cells was CD56bright and 20% was CD56dim. NK cells collected at day 20 (□) were activated for 2 days with 100 IU/mL IL-2. Cytotoxicity for both NK lines was measured by 51Cr release assay against K562 target cells. (Right) NK cells from unrelated healthy donor were activated 2 days (□) and 8 days (♦) with 100 IU/mL IL-2 and tested against K562. This result is representative of 2 different experiments.

Distribution of CD56dimand CD56brightNK cells subsets after haploidentical SCT. (A, top) FACS profile of CD3-CD56dim (□) and CD3-CD56bright (▪) subpopulations of CD3-CD56+ NK cells in 2 patients after haploidentical SCT (no. 8, no. 6), compared with their respective donors. Percentage of NK cells is presented from the engraftment (day 14) to the sixth or fourth month after SCT. Days after transplantation are indicated. (Bottom) Flow cytometric density plots are gated on CD3-CD56+ NK cells at 90 and 180 days after transplantation and are compared with donors. Percentage of CD3-CD56dim and CD3-CD56bright cells in the total CD3-CD56+ population are indicated. (B, left) Cytotoxicity of CD3-CD56bright NK cells compared with CD56dim NK cells against K562 target cells, for patient no. 8. At engraftment (day 14), all NK cells were CD56bright (♦). These cells were collected and then activated by 100 IU/mL IL-2 for 8 days. At day 20, PB from the same patient was collected: 80% of circulating NK cells was CD56bright and 20% was CD56dim. NK cells collected at day 20 (□) were activated for 2 days with 100 IU/mL IL-2. Cytotoxicity for both NK lines was measured by 51Cr release assay against K562 target cells. (Right) NK cells from unrelated healthy donor were activated 2 days (□) and 8 days (♦) with 100 IU/mL IL-2 and tested against K562. This result is representative of 2 different experiments.

Phenotypic analysis of the inhibitory NK receptor repertoire

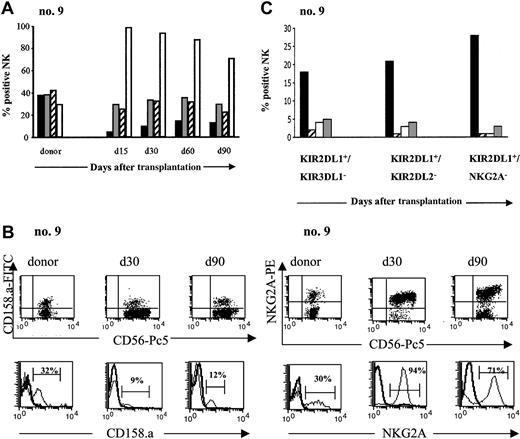

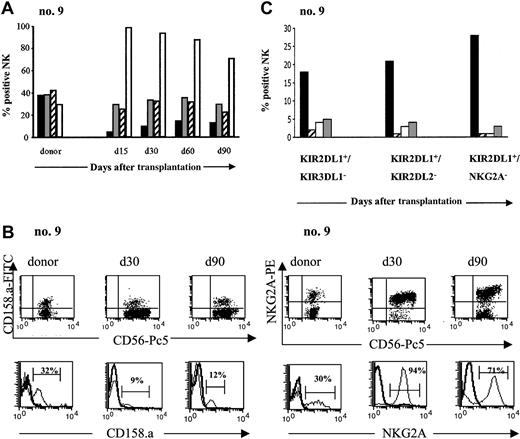

After transplantation, peripheral blood was sampled from each patient at monthly intervals for the next 4 months. NK-cell expression of CD94/NKG2A and 3 inhibitory KIRs, KIR2DL1 (CD158.a), KIR2DL2 (CD158.b), and KIR3DL1 (CD158.e), was determined by flow cytometry and compared with the same expression in the donor. Figure 3A illustrates the recovery of inhibitory NK-cell receptor expression in 1 patient, and similar results were obtained in all patients. KIR expression was lower in patients than in donors, throughout the 4-month period. The difference was greatest for KIR2DL1. The ratio of recipient-donor KIR2DL1 on NK cells was 0.27 at 1 month and 0.39 at 4 months after SCT. Kinetic analysis of the ratio for these KIRs (Table 3) showed the same level of KIRs at 4 months as at engraftment.

In striking contrast to the weak KIR expression, CD94/NKG2A was expressed by the great majority of circulating NK cells during the 4 months following the SCT. The percentage of circulating NK cells expressing CD94/NKG2A was 96% ± 4% at 1 month (range, 90%-100%) and 79% ± 21% at 4 months (range, 41%-97%), compared with 41% ± 18% among donors (range, 26%-73%) (Figure 3B). The recipient-donor ratio was thus 2.6 ± 1.03 at 1 month and 2 ± 0.54 at 4 months (Table 3). The sharp rise in CD94/NKG2A expression in all patients appeared to counterbalance the low expression of inhibitory KIRs and reflects a defect in the differentiation of NK cells reconstituted from the CD34+ grafts.

According to Ruggeri et al,6,7 the presence of donor alloreactive NK cells should eliminate host tumor cells and thereby improve survival. Alloreactive NK cells are defined as NK cells whose inhibitory HLA class I ligand is missing in the recipient.25 We hypothesized that the alloreactive NK subset expands after transplantation. To test this hypothesis, we conducted phenotypic analyses to assess the frequency of putative donor-versus recipient alloreactive NK cells for each patient. A similar phenomenon was observed in all cases, exemplified in transplantation no. 9: donor and recipient were mismatched for group 2 HLA-C ligands, which bind KIR2DL1. The donor alloreactive NK subset should therefore express KIR2DL1 (because KIR2DL1 ligand is missing in recipient) but not KIR2DL2 or KIR3DL1 (because the ligands for those 2 receptors are present in the recipient). According to 4-color cytofluorimetric analysis, however, after SCT, the recipient has an extremely low level of this putative alloreactive population, KIR2DL1+/KIR2DL2- or KIR3DL1- (Figure 3C), and it did not expand during the 5 months after SCT.

Phenotypic analysis of the activating NK receptor repertoire

We further investigated whether activating receptors were normally expressed on CD3-CD56+ NK cells after engraftment. Cell surface expression of the 3 NCRs, NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46, was analyzed by FACS and compared with donor phenotypes. Normally, in the donors, NKp30 and NKp46 are expressed constitutively on resting NK cells, while NKp44 expression on NK cells requires activation with IL-2.26 At 1 month, NKp46 expression by the NK cells of the 6 patients tested was similar to that of the resting, mature NK cells isolated from their donors (Figure 4A). In contrast, however, NKp30 levels were much lower in patients than in donors; the recipient-donor ratio of NKp30 on NK cells at 1 month was 0.58 ± 0.1. This low level of expression persisted throughout the follow-up, with a ratio of 0.35 ± 0.06 at 4 months (Figure 4A). Interestingly, although resting mature NK cells from donors did not constitutively express NKp44 (0.8% ± 0.8%), after transplantation, 3% to 20% of circulating NK cells after transplantation did. This NKp44 expression was restricted to the CD3-CD56bright NK cells and was sometimes observed on up to 60% of this subset (Figure 4B).

We note that the phenotype of the NK cells derived at 4 months after SCT from all 6 patients was similar to that detected at engraftment: no in vivo differentiation had occurred.

Pattern of inhibitory receptor expression on CD3-CD56+NK cells after haploidentical SCT. (A) PB from donor and patient (no. 9) after SCT was stained with various inhibitory receptors: KIR2DL1 (CD158.a ▪), KIR2DL2 (CD158.b ▦), KIR3DL1 (CD158.e ▨), and CD94/NKG2A (□). Percentage of CD3-CD56+ cells positive for those receptors are represented from day 15 to day 90 and compared with donor. Days after transplantation are indicated. (B) Expression of KIR2DL1 (CD158.a) and CD94/NKG2A on NK cells from donor and patient (no. 9) after SCT. Flow cytometric density plots and histograms are gated on CD3-CD56+ NK cells. (C) Evolution of the putative alloreactive NK subset after SCT compared with the donor. Results obtained in the donor (▪) and in patient no. 9 at the engraftment (▨), day 30 (□), and day 90 (▦) after SCT are shown. The alloreactive NK subset was analyzed by 4-color flow cytometry expressed KIR2DL1 but not KIR3DL1 or KIR2DL2 or CD94/NKG2A. Results are expressed as the percentages of the alloreactive NK subset in the total NK population.

Pattern of inhibitory receptor expression on CD3-CD56+NK cells after haploidentical SCT. (A) PB from donor and patient (no. 9) after SCT was stained with various inhibitory receptors: KIR2DL1 (CD158.a ▪), KIR2DL2 (CD158.b ▦), KIR3DL1 (CD158.e ▨), and CD94/NKG2A (□). Percentage of CD3-CD56+ cells positive for those receptors are represented from day 15 to day 90 and compared with donor. Days after transplantation are indicated. (B) Expression of KIR2DL1 (CD158.a) and CD94/NKG2A on NK cells from donor and patient (no. 9) after SCT. Flow cytometric density plots and histograms are gated on CD3-CD56+ NK cells. (C) Evolution of the putative alloreactive NK subset after SCT compared with the donor. Results obtained in the donor (▪) and in patient no. 9 at the engraftment (▨), day 30 (□), and day 90 (▦) after SCT are shown. The alloreactive NK subset was analyzed by 4-color flow cytometry expressed KIR2DL1 but not KIR3DL1 or KIR2DL2 or CD94/NKG2A. Results are expressed as the percentages of the alloreactive NK subset in the total NK population.

Functional analysis of NK cells generated after transplantation

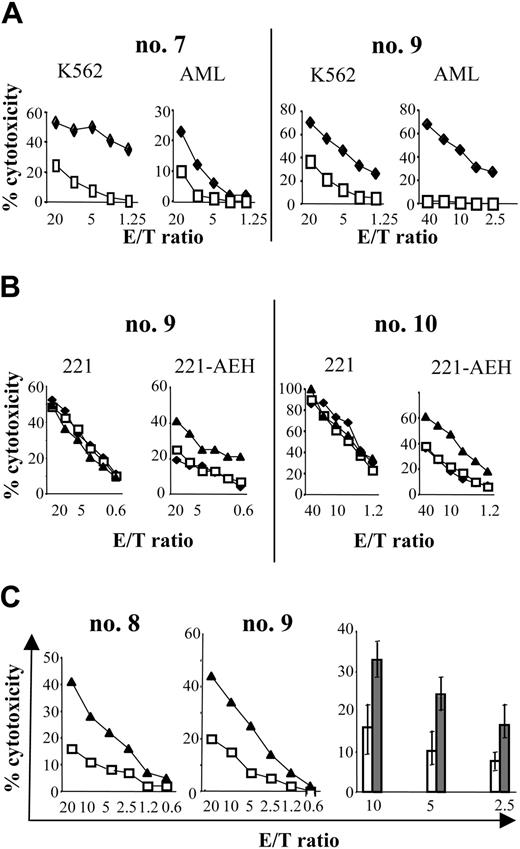

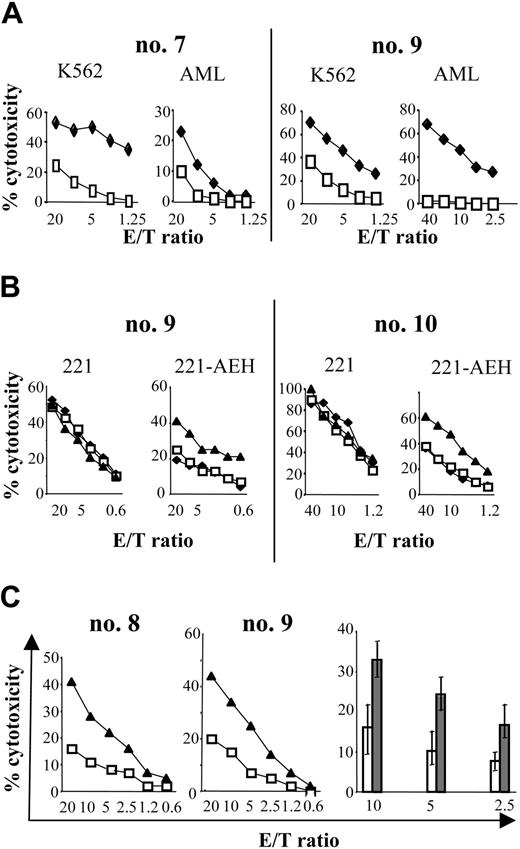

The phenotypic abnormalities described above concerning NK-cell differentiation after SCT suggest that the functional capacity of the NK-cell compartment is impaired during early recovery from SCT. To verify this possibility, we assessed the cytolytic activity against K562 cells and recipient primary leukemic blasts. Figure 5A reports a representative experiment conducted with NK cells generated in 2 recipients at engraftment or at 1 month after the graft. The cytotoxic potential of these cells against K562 was around 3-fold lower (at an effector-target [E/T] ratio, 10:1) than that of donor NK cells. Concomitantly, their cytotoxicity against recipient primary AML blasts was poorer than the donor cells, despite the HLA mismatch in the GvH direction. This finding ruled out the possibility that the minimal lysis observed was due to any specific HLA mismatch, but results were similar for patients mismatched for Cw group 1 ligands, Cw group 2 ligands, or Bw4 (data not shown).

As previously observed, nearly all the circulating NK cells sampled during the first 4 months after SCT expressed CD94/NKG2A. To evaluate the involvement of CD94/NKG2A in the low levels of NK-mediated lysis, we assessed the cytolytic activity of the NK cells against target cells that did or did not express HLA-E, the ligand of CD94/NKG2A (Figure 5B-C). As Figure 5B shows, activated NK cells generated in the recipient after the SCT were cytotoxic against untransfected LCL-721-221 cells, but cytotoxicity was much lower against the HLA-E-transfected 721-221 cells, which suggests that HLA-E expression by target cells inhibited lysis. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of HLA-E was blocked when anti-NKG2A mAb was present: in that case, the blockade of NKG2A partially restored the lysis against HLA-E-transfected 721-221 cells (see Figure 5B). This suggests that some interaction between HLA-E and CD94/NKG2A mediates this inhibition of cytotoxicity.

Further studies used the primary AML blasts as the target. HLA-E expression by the AML blasts was verified by Western blot (data not shown). Activated NK cells isolated from the peripheral blood after SCT were tested for cytotoxicity against AML blasts in the presence and absence of anti-NKG2A mAb. Figure 5C describes the results of a representative experiment for 2 patients. In line with the results observed in Figure 5A, a very low level of cytotoxicity was detected against the AML blast, despite the HLA mismatch in the GvH direction. Cytotoxicity increased strongly in the presence of anti-NKG2A mAb (Figure 5C). Together, these results suggest that the expression of CD94/NKG2A by a great majority of NK cells after SCT could take part in the absence of GvL effect, despite the KIR ligand mismatch.

Discussion

We show here that a purified CD34+ haploidentical SCT provides a useful system for examining the in vivo reconstitution of NK cells after transplantation. The inoculum was depleted of mature donor T and NK cells, and GvHD was not observed in any patients. A serious problem in the transplantation of T-cell-depleted grafts is the increased risk of relapse after transplantation, due to the loss of the GvL effect that T cells mediate. The NK cells, therefore, because they reconstitute much faster than T cells after SCT, must induce the GvL effect in this type of transplantation. The role of NK-cell alloreactivity in the outcome of transplantations for tumoral hematopoietic disease is a topic of debate. Some studies report that SCT with KIR ligand incompatibility27-30 provides no survival advantage or even results in a disadvantage, whereas Ruggeri et al6 report impressive control of AML relapse for patients who receive transplants with a KIR/HLA mismatch in the GvH direction. Others obtained similar results in unrelated SCT without any ex vivo T-cell depletion and with 1 or more HLA mismatches in the GvH direction.8 Discrepancies in these clinical results may well reflect heterogeneity in the transplantation protocols at different treatment centers, including disease type and status, use of anti-T-cell globulin before transplantation, graft source, degree of its T-cell depletion, occurrence of GvHD, and use of immunosuppressive drugs. Clearly, further study will be required before these clinical results can be fully reconciled.

Pattern of activating receptors expression on CD3-CD56+NK cells after haploidentical SCT. (A, left) Frequency of CD3-CD56+ NK cells expressing NCRs NKp30, NKp44, or NKp46, in 2 donor-recipient pairs (no. 10, no. 9). Cells were stained at the time of engraftment (day 15) and in the months thereafter. Results are expressed as the percentage of CD3-CD56+ cells positive for NKp30 (▪), NKp44 (▦), or NKp46 (□). (Right) Representative histogram analysis of each NCR for 1 patient (no. 10) at 90 days after graft, compared with the donor. (B, top) NKp44 is expressed mostly on CD3-CD56bright NK cells. Percentage of CD3-CD56dim (▪) or CD3-CD56bright NK cells (□) expressing NKp44 in the total population of CD3-D56dim or CD3-CD56bright NK cells are represented at different times after SCT and compared with the donor. M indicates month. (Bottom) FACS distribution of NKp44+ NK cells in CD3-CD56dim and CD3-CD56bright subpopulations is indicated for patient no. 10 at day 90. Values shown are percentage of NK cells (gated by CD3-CD56+) that expressed NKp44 in the various quadrants.

Pattern of activating receptors expression on CD3-CD56+NK cells after haploidentical SCT. (A, left) Frequency of CD3-CD56+ NK cells expressing NCRs NKp30, NKp44, or NKp46, in 2 donor-recipient pairs (no. 10, no. 9). Cells were stained at the time of engraftment (day 15) and in the months thereafter. Results are expressed as the percentage of CD3-CD56+ cells positive for NKp30 (▪), NKp44 (▦), or NKp46 (□). (Right) Representative histogram analysis of each NCR for 1 patient (no. 10) at 90 days after graft, compared with the donor. (B, top) NKp44 is expressed mostly on CD3-CD56bright NK cells. Percentage of CD3-CD56dim (▪) or CD3-CD56bright NK cells (□) expressing NKp44 in the total population of CD3-D56dim or CD3-CD56bright NK cells are represented at different times after SCT and compared with the donor. M indicates month. (Bottom) FACS distribution of NKp44+ NK cells in CD3-CD56dim and CD3-CD56bright subpopulations is indicated for patient no. 10 at day 90. Values shown are percentage of NK cells (gated by CD3-CD56+) that expressed NKp44 in the various quadrants.

Ruggeri et al6,7 have conducted extensive in vitro studies of NK cells from the donors and recipients in their cohort. Their analysis of alloreactive NK cells is based mainly on mature NK cells collected from donors before transplantation and on a few NK clones from recipients after transplantation. Their in vitro assay studied NK clones amplified from a purification of CD16+ cells, which represent a subset of NK cells decreased after SCT.31,32 In our study, the mean expression of CD16, in the whole population of NK cells, was 97% (range, 96%-98%) in the donors versus 55% (range, 47%-68%) in the recipients after transplantation. Thus, CD3-CD56+/CD16+ cells were not fully representative of the NK population after haploidentical SCT. Accordingly, selecting CD16+ cells may bypass the major problem of NK-cell differentiation that we observed in the first months after the grafts. Most of the pairs in our study were mismatched for KIR ligand in the GvH direction, and we expected that alloreactive NK cells would mediate a GvL effect. Strikingly, relapses occurred in the early posttransplantation period in 7 of these 10 patients who received highly purified CD34+ cell transplants. Our clinical results motivated us to study the reconstitution of NK cells after haplo-SCT and to evaluate their functionality. Our approach to these in vitro experiments was very different from Ruggeri et al.6,7 We did not work on clones but on the entire NK-cell population, for which we performed kinetic phenotypic and functional assays that we compared with donor samples.

Ex vivo analysis of NK differentiation after engraftment of extensively T-cell-depleted mismatched CD34+ cell transplants revealed that NK cells recovered rapidly. They were observed in large quantities (up to 95% of circulating lymphocytes) from engraftment. These high NK-cell fractions were usually accompanied by a disproportional 17-fold increase in the ratio of CD3-CD56bright to CD3-CD56dim NK cells, a finding consistent with earlier observations.31,32 The patterns of NK-cell receptor expression during the first 4 months after transplantation revealed that the frequency of KIR-positive NK cells remained very low for all patients, and, the frequency of CD94/NKG2A and KIR were inversely correlated: almost all the NK cells expressed CD94/NKG2A. We observed no amplification of alloreactive NK populations, defined phenotypically by the expression of 1 inhibitory receptor that does not match an HLA class I ligand from the recipient. If we also consider CD94/NKG2A in the definition of alloreactive NK cells, this subset, which does not express CD94/NKG2A, is even smaller (Figure 3C). Recently, Pende et al25 showed that the size of NK-cell subset expressing KIR not engaged by the HLA class I alleles of the patient was correlated with the degree of NK cytotoxicity against leukemic cells.

Taken together, our data provide direct evidence that differential expression of both KIRs and CD94/NKG2A lectin-like receptor is coordinated during NK-cell development. Indeed, those 2 types of receptors share a common purpose to avoid autoreactivity. We also analyzed the acquisition of triggering receptors and found NKp30 levels to be low during the 4 to 6 months after engraftment. Vitale et al33 observed decreased NKp30 and NKp46 expression in a few patients after allogeneic matched SCT, but this decrease was transient and expression normalized at 1 month after SCT.

This low level of NKp30 might be consistent with an immature NK phenotype, which persisted in our study throughout the follow-up (maximum, 6 months). Analysis of the cytolytic activity of these NK cells showed that their cytotoxicity against the HLA class I-deficient K562 cells and against recipient mismatch AML blasts was severely impaired. This finding is consistent with earlier observations.31 In addition, NKG2D expression by NK cells was not affected after SCT, and the expression of its ligands, MHC class I chain-related A or B (MICA/B), was not detected in AML blasts (data not shown). This suggests that the interaction between NKG2D and its ligands might not be important in the NK lysis against AML blasts, as recently reported.25

Cytolytic activity of NK cells after haploidentical SCT and inhibitory effect of CD94/NKG2A on NK cells. (A) Lower lysis activity by NK cells from SCT (□) than by NK cells from healthy donor (♦). NK cells from 2 patients were tested at engraftment (no. 7) or at 1 month after SCT (no. 9). NK cytolytic activity was tested against K562 target cells (K562) and mismatched primary AML targets (AML). Similar results were obtained with recipient primary AML blast. Primary AML blasts presented both distinct mismatches; in HLA-Cw of the group 2/KIR2DL2 (no. 7) or in HLA-Cw of the group 1/KIR2DL1 (no. 9). (B) Expression of HLA-E on target cells inhibited cytotoxicity of NK cells after haploidentical SCT by CD94/NKG2A. NK cells from 2 patients were tested at 3 months (no. 10) or at 1 month after SCT (no. 9) for cytotoxicity against LCL-721-221 target (221) or against LCL transfected by HLA-E (221-AEH; B2, B4). NK cells were incubated with media alone (♦), anti-IgG2b isotype control (□), or anti-NKG2A mAb (▴). Results are representative of 3 different experiments. (C) Cytotoxicity of NK cells from haploidentical SCT against primary leukemic AML blasts was restored by blocking NKG2A. (Left) Activated NK cells from 2 patients (no. 8, no. 9) were tested at 2 months after SCT for cytotoxicity against mismatched AML blasts. Primary AML blasts presented both distinct mismatches in Bw6/KIR3DL1/Cw group1/KIR2DL1 (no. 8) or Cw group 1/KIR2DL1 (no. 9). NK cells were incubated with anti-IgG2b isotype control (□) or anti-NKG2A mAb (▴). (Right) Percentage of lysis against mismatched AML blast at different effector-target (E/T) ratio. NK cells after transplantation were incubated with anti-IgG1 isotype control (□) or anti-NKG2AmAb (▦). Results show the mean of 6 different experiments and their standard deviation.

Cytolytic activity of NK cells after haploidentical SCT and inhibitory effect of CD94/NKG2A on NK cells. (A) Lower lysis activity by NK cells from SCT (□) than by NK cells from healthy donor (♦). NK cells from 2 patients were tested at engraftment (no. 7) or at 1 month after SCT (no. 9). NK cytolytic activity was tested against K562 target cells (K562) and mismatched primary AML targets (AML). Similar results were obtained with recipient primary AML blast. Primary AML blasts presented both distinct mismatches; in HLA-Cw of the group 2/KIR2DL2 (no. 7) or in HLA-Cw of the group 1/KIR2DL1 (no. 9). (B) Expression of HLA-E on target cells inhibited cytotoxicity of NK cells after haploidentical SCT by CD94/NKG2A. NK cells from 2 patients were tested at 3 months (no. 10) or at 1 month after SCT (no. 9) for cytotoxicity against LCL-721-221 target (221) or against LCL transfected by HLA-E (221-AEH; B2, B4). NK cells were incubated with media alone (♦), anti-IgG2b isotype control (□), or anti-NKG2A mAb (▴). Results are representative of 3 different experiments. (C) Cytotoxicity of NK cells from haploidentical SCT against primary leukemic AML blasts was restored by blocking NKG2A. (Left) Activated NK cells from 2 patients (no. 8, no. 9) were tested at 2 months after SCT for cytotoxicity against mismatched AML blasts. Primary AML blasts presented both distinct mismatches in Bw6/KIR3DL1/Cw group1/KIR2DL1 (no. 8) or Cw group 1/KIR2DL1 (no. 9). NK cells were incubated with anti-IgG2b isotype control (□) or anti-NKG2A mAb (▴). (Right) Percentage of lysis against mismatched AML blast at different effector-target (E/T) ratio. NK cells after transplantation were incubated with anti-IgG1 isotype control (□) or anti-NKG2AmAb (▦). Results show the mean of 6 different experiments and their standard deviation.

NK receptors and effector functions seem to be acquired in a specific order.34,35 In vitro analysis of NK-cell differentiation from CD34+ stem cells revealed that most of the immature NK cells expressed both the CD56bright surface antigen and the CD94/NKG2A inhibitory receptor.34 At the same time, no KIR expression could be detected, and NCR expression remained low. Consistently with these findings, weak cytotoxicity against HLA class I-negative or -positive target cells was observed. In addition, immature NK cells mediated TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-dependent, but not Fas ligand or granule-release dependent, cytotoxicity.36,37 In the presence of suitable cytokines and stromal cells, however, CD34+ cells became CD56dim and rapidly acquired large quantities of NCR KIR receptors and intracellular perforin. At this stage the NK cells were cytotoxic.34 Looking for this sequential acquisition of receptors and functions in our study, however, we find instead that NK cells generated in vivo after haplo-SCT had an immature phenotype, and the particularity of our cohort is the persistence of this immature phenotype for at least 6 months. This early period seems to be crucial for tumor progression, since all the patients relapsed between the third and sixth months after SCT. The feature most likely to explain the absence of lysis against the recipient leukemic blasts was the persistence of the expression of CD94/NKG2A by the majority of NK cells after transplantation. Inhibition of lysis was mediated by the CD94/NKG2A heterodimer, by recognition of HLA-E, which is expressed by all the cells of an individual that express normal amount of classic MHC class I molecules.23,38 High expression of CD94/NKG2A by immature NK cells in murine models appears to prevent most neonatal and prenatal NK cells from attacking self-cells.39,40 As we have seen here, myeloid leukemic blasts also express HLA-E, and this expression inhibited their lysis by NK cells isolated ex vivo after haplo-SCT. This inhibition was mediated by HLA-E recognition by CD94/NKG2A, which plays a role in preventing both autoreactivity, but also GvL effect. Shilling et al41 analyzed the NK repertoire generated after HLA-matched SCT and reported a similar profile with high expression of CD94/NKG2A and low expression of KIRs. In that study, the NK repertoire after SCT then tended to recapitulate the donor repertoire in 6 months to 3 years. The similarity of the profile of inhibitory receptors found in both HLA-matched SCT and in the present study suggests that the HLA environment is not the dominant factor that influences immature phenotype. The impairment of NK functions observed in vitro seemed thus to be correlated with the immature phenotype and with the high relapse rate in vivo, despite the KIR incompatibility between donor and recipient.

It remains unknown why NK cells remained immature after haplo-SCT. Intensive conditioning with TBI and myeloablative treatments for SCT may impair bone marrow stromal cells, which are essential for the maturation of NK cells.17 Furthermore, the very small number of mature T cells after CD34+ SCT may affect NK-cell development. Fehniger et al42 showed that the proportion of CD3-CD56bright NK cells in the lymph nodes of healthy donors is high and that T cells activate them. This suggests that NK precursors may travel from the bone marrow to the lymph nodes for maturation and then differentiate into mature NK cells in the periphery. Similarly, several studies propose that dendritic cells (DCs) play a key role in promoting NK-cell functions. It even appears that direct DC/NK-cell cross talk modulates NK cells functions.42-44 Furthermore, Ferlazzo et al45 observed that NK cells recognize DCs by the NKp30 receptor. In our study, we observed a specific decrease in NKp30 expression on NK cells from patients after transplantation. This suggests a regulatory circuit between NK cells and DCs, in which NK cells require DCs for maturation.

In conclusion, there is currently considerable excitement over the potential of haploidentical SCT and renewed interest in NK-cell clinical applications. However, elucidation of the inhibition of NK-cell differentiation will be crucial to determine the contribution of NK cells to the GvL effect.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 1, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4113.

Supported by grants from the Association Cent pour Sang la Vie and Fondation de France. S.N. was supported by a fellowship from Caisse Nationale d'Assurance Maladie des Professions Indépendantes (CANAM)/Assistance Publique et Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Sophie Hilpert for her excellent technical assistance.