Abstract

The Kit receptor tyrosine kinase is critical for normal hematopoiesis. Mutation of the aspartic acid residue encoded by codon 816 of human c-kit or codon 814 of the murine gene results in an oncogenic form of Kit. Here we investigate the role of protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) in responses mediated by wild-type murine Kit and the D814Y mutant in a murine mast cell-like line. PKCδ is activated after wild-type (WT) Kit binds stem cell factor (SCF), is constitutively active in cells expressing the Kit catalytic domain mutant, and coprecipitates with both forms of Kit. Inhibition of PKCδ had opposite effects on growth mediated by wild-type and mutant Kit. Both rottlerin and a dominant-negative PKCδ construct inhibited the growth of cells expressing mutant Kit, while SCF-induced growth of cells expressing wild-type Kit was not inhibited. Further, overexpression of PKCδ inhibited growth of cells expressing wild-type Kit and enhanced growth of cells expressing the Kit mutant. These data demonstrate that PKCδ contributes to factor-independent growth of cells expressing the D814Y mutant, but negatively regulates SCF-induced growth of cells expressing wild-type Kit. This is the first demonstration that PKCδ has different functions in cells expressing normal versus oncogenic forms of a receptor.

Introduction

Kit, the receptor for stem cell factor (SCF), is a type III receptor tyrosine kinase of the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) subfamily. c-kit maps to the white spotting (W) locus in the mouse,1,2 while the gene for its ligand SCF maps to the steel (Sl) locus.3,4 Mutations that reduce function or expression of either the receptor or ligand lead to macrocytic anemia, mast cell deficiency, abnormal pigmentation of skin and hair, infertility, reduced gastrointestinal motility, and impaired hippocampal learning.5 Gain-of-function mutations in Kit can be oncogenic and are found in various diseases including leukemias, mastocytosis, germ cell tumors, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).6 One common gain-of-function mutation is the substitution of valine, tyrosine, asparagine, or histidine for aspartic acid 816 in the catalytic domain of human Kit. Mutations of codon 816 have been identified in patients with mastocytosis,7-10 acute myeloid leukemia (AML),11-13 and germ cell tumors.14 Mutations of the corresponding codon (D814 in mice, D817 in rats) have been found in a murine mastocytoma cell line P-81515 and a rat mast cell tumor line RBL-2H3.16 Expression of D814Y/V Kit in the murine mast cell-like line IC2, as well as several other factor-dependent hematopoietic cell lines, results in factor-independent growth and tumorigenesis.17-20 Interestingly, cells expressing a Kit catalytic domain mutant are resistant to STI571/imatinib (Gleevec), an inhibitor of wild-type (WT) Kit.21-23 Thus, drugs targeting this mutant receptor or its downstream effectors could be useful therapeutic agents in the treatment of diseases associated with this mutation.

The protein kinase C (PKC) family of serine-threonine protein kinases encompasses at least 12 members,24 which can be separated into 3 classes: conventional, novel, and atypical. The conventional PKCs include the α, β, and γ isoforms. Activation of these PKCs requires both calcium ions and a lipid, such as diacylglycerol (DAG) or phosphatidylserine, or a phorbol ester. The novel PKCs, including δ, ϵ, η, and θ isoforms, are calcium-independent and require only a lipid or a phorbol ester for kinase activity. Unlike the conventional isoforms, the novel isoforms can be activated by the products of phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase (PI3K), PtdIns-3,4-P2, or PtdIns-3,4,5-P3, as well as DAG or phosphatidylserine.25 The atypical PKCs, including the ζ and λ isoforms, require neither calcium nor a lipid or phorbol ester for kinase activity.

PKC isoforms are reported to phosphorylate wild-type (WT) Kit on serine residues after stimulation with SCF. Previous work has shown that this reduces autophosphorylation activity and subsequent interaction with a variety of signaling components.26,27 Importantly, these studies were performed in porcine aortic endothelial cells, which predominantly express the conventional PKC isoforms α and β. The role of novel PKC isoforms in signaling through WT Kit has not been addressed. Further, little is known about the role of PKC isoforms in transformation mediated by oncogenic Kit mutants. Interestingly, recent work has implicated PKCδ in B-cell lymphocytic leukemia28 and multiple myeloma.29

The objective of this study was to investigate the role of PKCδ in responses mediated by a normal and an oncogenic form of Kit. We found that while PKCδ is activated after SCF stimulation of WT Kit and is constitutively active in cells expressing the D814Y mutant, it plays a different role in growth mediated by these 2 forms of Kit.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

IC2 cells are an interleukin-3 (IL-3)–dependent murine mast cell-like cell line that is syngeneic with the DBA2 strain. IC2 cells stably transfected with WT Kit or D814Y Kit19 were grown in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamate (PSG Gibco), and 10 ng/mL murine IL-3 (Pepro Tech, Rocky Hill, NJ) at 37°C/5% CO2.

Drugs and antibodies

Rottlerin and Gö6976 were purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for PKCδ (C17 and C20), Kit (C19), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3, K15) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). A goat polyclonal antibody specific for Kit (M14), which was used for immunoprecipitation, and the antiphosphotyrosine antibody PY99 were also purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies specific for phosphotyrosine 705 of STAT3 and phosphoserine 727 of STAT3 were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Protein A–sepharose beads were purchased from Amersham (Uppsala, Sweden) and Protein G Plus sepharose beads were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies specific for rabbit, goat, and mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated streptavidin were purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories (Gaithersburg, MD).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% FBS and 1% PSG and then resuspended at 2 × 107 cells/mL. Cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes in the presence or absence of 100 ng/mL murine SCF (Pepro Tech) and then lysed. Whole cell lysates were prepared using a high phosphatase inhibitor (HPI) lysis buffer (1% Triton-X-100, 10 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]–HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 30 mM tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mg/mL p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and 5 mM sodium fluoride, pH 7.5). Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 minutes and then centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. Clarified lysates were stored at –70°C. Membrane-enriched fractions were prepared as follows: Cells were resuspended in hypotonic 5/5/5 buffer (5 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA [ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid], pH 7.5) and kept on ice for 15 minutes before being drawn 4 times through a 22-gauge needle then 4 times through a 27-gauge needle. Membranes were pelleted at 35 000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C in a SW50.1 rotor in a Beckman ultracentrifuge (Palo Alto, CA). Pellets were resuspended in HPI buffer and rotated for 2 hours at 4°C to solubilize. Triton-X-100–insoluble material was pelleted and discarded. Membrane-enriched fractions were stored at –70°C. The protein concentrations of the clarified lysates and membrane preparations were determined using the bicinchinonic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Depending upon the experiment, between 300 and 800 μg protein and 1 μg antibody were used per immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Immunoblots were blocked in TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2% goat serum, and 1% liquid gelatin. Primary and secondary antibodies and HRP-conjugated streptavidin were diluted in TBST with 0.1% BSA and 1% liquid gelatin. Immunoblots were developed with Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagent (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) or with Super Signal chemiluminscent substrate (Pierce). Immunoblots were visualized by exposure to Biomax film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Immunoblots were stripped with ReBlot Plus (Chemicon, Temecula, CA).

Cell proliferation assays

IC2 cells were washed 3X with RPMI with 10% FBS and resuspended at 1 × 105 cells/mL. Cells (100 μL [104]/well) were seeded in quadruplicate samples in 96-well plates. The cells were then preincubated with rottlerin or Gö6976 for 1 hour 20 minutes or 1 hour, respectively, prior to the addition of media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF for cells expressing WT Kit. Media with 10% FBS alone or media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF were added to cells expressing D814Y Kit. After the addition of growth factor, the cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 hours and then 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) 3H-thymidine (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) was added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37°C for another 4 hours before harvesting with a Mach II M cell harvester (Tomtec, Hamden, CT). Cell growth was assayed by 3H-thymidine incorporation assessed by liquid scintillation counting. Cell growth in the presence of rottlerin or Gö6976 was normalized to cell growth in the absence of drug.

Plasmids and transfection

IC2 cells were transfected with 15 μg wild-type or dominant-negative PKCδ in metallothionein promoter-driven (MTH) vector30 or with empty MTH vector31 by electroporation. Transfection efficiency was 30% to 40% based on a green fluorescent protein control. After transfection, cells were diluted in growth media with 20% FBS and transferred to 6-well plates. At 24 hours after transfection, cells were washed 3 times with RPMI with 10% FBS and resuspended at 1 × 105 viable cells/mL. Cells (100 μL [104]/well) were seeded in 96-well plates. Quadruplicate samples received either media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (WT Kit and D814Y transfectants) or 10% FBS alone (D814Y Kit transfectants). Cells were incubated for 48 hours before the addition of 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) 3H-thymidine/well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for another 6 hours before harvesting. Cell growth was assayed by 3H-thymidine incorporation assessed by liquid scintillation counting.

PKCδ kinase assay

PKCδ was immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates or membrane-enhanced fractions in HPI buffer using the C17 PKCδ antibody and protein A–sepharose beads. The beads were washed twice with HPI buffer and then twice with kinase buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) with 2.5X Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). A master mix of kinase buffer supplemented with 20 μg/mL l-α–phosphatidylserine (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 40 μM adenosine triphosphate (ATP; Roche), 10 μCi (0.37 MBq)/reaction γ32P ATP (NEN, Boston, MA), and 1 μg/reaction myelin basic protein or 2 μg/reaction histone H1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) was added to the beads, which were then incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS buffer. Samples were boiled and then run on 4% to 20% Tris-glycine gradient gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in SDS running buffer (BioRad, Hercules, CA), transferred to immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and visualized by autoradiography.

Results

PKCδ is activated by WT Kit and is constitutively active in cells expressing D814Y Kit

Mutation of codon 816 of human Kit is frequently associated with mastocytosis. Mutation of the corresponding codon in mice (814) and rats (817) is also associated with mast cell disease.15,16 We sought to study WT Kit and a catalytic domain mutant in a cellular background similar to one in which a disease state associated with this mutant occurs in vivo. Consequently, we used IC2 cells, a murine mast cell-like line. These cells do not express Kit, so cells stably expressing WT or D814Y murine Kit were generated by retroviral infection.19 IC2 cells expressing WT Kit were factor dependent and grew in response to either SCF or IL-3. In contrast, IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit were factor independent and tumorigenic in mice.19,20

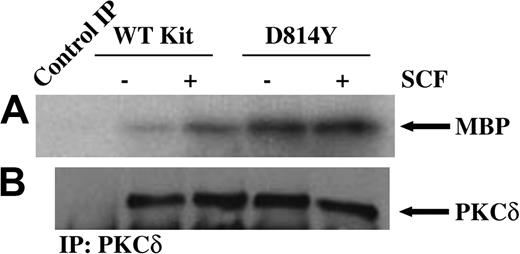

To investigate the role of PKCδ in responses mediated by a normal and an oncogenic form of Kit, we first examined PKCδ activity in IC2 cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit. In vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed on PKCδ immunoprecipitated from equivalent amounts of protein from whole cell lysates of cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit. As shown in Figure 1A, treatment of cells expressing WT Kit with SCF induces an increase in PKCδ activity. Further, PKCδ is constitutively active in cells expressing the D814Y mutant. Consistent with the requirements for PKCδ activation, kinase activity was lipid dependent and Ca++ independent (data not shown). Figure 1B confirms that equivalent amounts of PKCδ were present in each of the kinase reactions. Further, staining of the blots with Ponceau S indicated that equivalent amounts of substrate were present in each of the reactions (data not shown). These data indicate that PKCδ is activated after stimulation of WT Kit by SCF and is constitutively active in cells expressing D814Y Kit. Further, PKCδ activity is higher in cells expressing D814Y Kit than cells expressing WT Kit.

PKCδ is constitutively active in cells expressing D814Y Kit. In vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed using whole cell lysates from cells expressing wild-type (WT) or D814Y Kit. (A) IC2 cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to lysis. Whole cell lysate protein (800 μg per sample) was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were incubated with γ32PATP, phosphatidylserine, and myelin basic protein (MBP) as a substrate. Samples were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature before resolution by SDS-PAGE and transfer to immobilon-P. Substrate phosphorylation was visualized by exposure to autoradiography film. (B) Membranes were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ. These data are representative of results from more than 3 experiments.

PKCδ is constitutively active in cells expressing D814Y Kit. In vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed using whole cell lysates from cells expressing wild-type (WT) or D814Y Kit. (A) IC2 cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to lysis. Whole cell lysate protein (800 μg per sample) was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were incubated with γ32PATP, phosphatidylserine, and myelin basic protein (MBP) as a substrate. Samples were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature before resolution by SDS-PAGE and transfer to immobilon-P. Substrate phosphorylation was visualized by exposure to autoradiography film. (B) Membranes were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ. These data are representative of results from more than 3 experiments.

Cells expressing D814Y Kit have more tyrosine phosphorylated PKCδ associated with the plasma membrane than cells expressing WT Kit

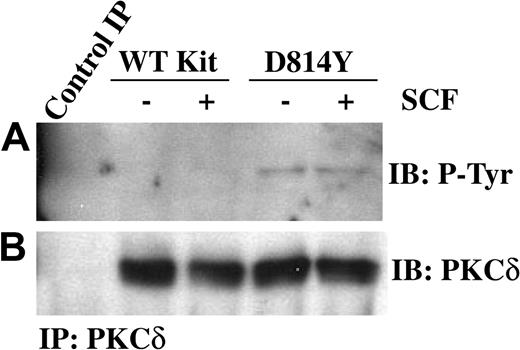

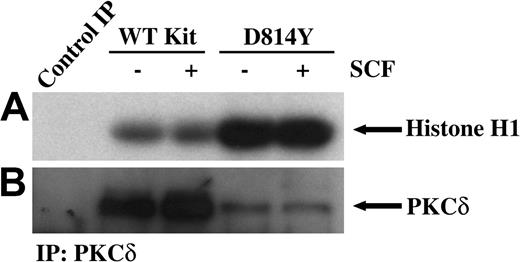

PKCδ undergoes a multistep phosphorylation process to become fully mature and capable of activation by lipids or phorbol esters. Immature forms of PKCδ are cytosolic, while mature PKCδ is localized at the cell membrane. PKCδ can be phosphorylated on tyrosine and this has been correlated with increases in PKCδ kinase activity.32,33 Thus we next examined tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ in membrane-enriched fractions from cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit. Figure 2A demonstrates an increase in the amount of tyrosine phosphorylated PKCδ associated with membranes from cells expressing D814Y Kit compared with cells expressing WT Kit. To evaluate the activity of PKCδ associated with the membrane, immune complex kinase assays were performed. Indeed, higher amounts of PKCδ activity were associated with membranes from cells expressing D814Y Kit than cells expressing WT Kit (Figure 3A). Ponceau S staining indicated that equivalent amounts of substrate were present (data not shown). Further, the higher levels of PKCδ activity were not mediated by increases in the amount of PKCδ protein in the membrane fractions of cells expressing D814Y Kit (Figure 3B). In fact, less PKCδ was observed in the samples from cells expressing D814Y Kit than cells expressing WT Kit (Figure 3B). This contrasts with the data shown in Figure 2B and likely results from the breakdown of activated PKCδ under the conditions of the kinase assay. These data indicate that PKCδ associated with the membranes of cells expressing D814Y Kit is phosphorylated on tyrosine and more active than PKCδ associated with the membranes of cells expressing WT Kit.

PKCδ associated with membranes from IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit is phosphorylated on tyrosine. IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to isolation of membranes. (A) Membrane protein (600 μg) from IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon-P, and immunoblotted with an antibody for phosphotyrosine. Membrane proteins immunoprecipitated with normal rabbit IgG were used as a negative control. (B) The immunoblots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with an antibody specific for PKCδ. These data are representative of results from 4 independent experiments. IB indicates immunoblot.

PKCδ associated with membranes from IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit is phosphorylated on tyrosine. IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to isolation of membranes. (A) Membrane protein (600 μg) from IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon-P, and immunoblotted with an antibody for phosphotyrosine. Membrane proteins immunoprecipitated with normal rabbit IgG were used as a negative control. (B) The immunoblots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with an antibody specific for PKCδ. These data are representative of results from 4 independent experiments. IB indicates immunoblot.

PKCδ associated with membranes from IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit has significantly greater kinase activity. In vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed using membrane-enhanced fractions from cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit. (A) IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to isolation of membranes. Membrane protein (400 μg per sample) was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ. The immunoprecipitates were incubated with γ32PATP, phosphatidylserine, and histone H1 as a substrate. Samples were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature before resolution by SDS-PAGE and transfer to immobilon-P. Substrate phosphorylation was visualized by exposure to autoradiography film. (B) Membranes were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ. These data are representative of results from more than 3 experiments.

PKCδ associated with membranes from IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit has significantly greater kinase activity. In vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed using membrane-enhanced fractions from cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit. (A) IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to isolation of membranes. Membrane protein (400 μg per sample) was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ. The immunoprecipitates were incubated with γ32PATP, phosphatidylserine, and histone H1 as a substrate. Samples were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature before resolution by SDS-PAGE and transfer to immobilon-P. Substrate phosphorylation was visualized by exposure to autoradiography film. (B) Membranes were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ. These data are representative of results from more than 3 experiments.

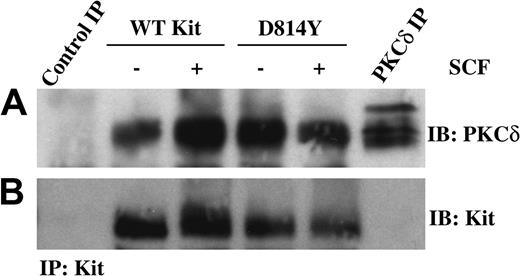

PKCδ is associated with wild-type and D814Y Kit

One mechanism to activate PKCδ could be through association with the Kit receptor complex. Therefore we next investigated whether PKCδ and Kit coimmunoprecipitated. Equivalent amounts of protein from whole cell lysates of IC2 cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit were immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for Kit and then immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ (Figure 4A). Interestingly, PKCδ coprecipitated with both wild-type and D814Y Kit. While multiple forms of PKCδ were observed in the PKCδ immunoprecipitate, the faster migrating form of PKCδ was found in each of the Kit receptor complexes. This may relate to preferential association of this species with Kit or Kit-associated proteins. The different sizes of PKCδ are likely related to the multiple phosphorylation states of this kinase or other secondary modification such as ubiquitination. Figure 4B demonstrates that similar amounts of Kit were present in each immunoprecipitate.

PKCδ is associated with WT and D814Y Kit. IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to lysis. (A) Whole cell lysate protein (600 μg per sample) was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for Kit, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon-P, and immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ. Lysate protein (600 μg) immunoprecipitated with normal goat IgG was included as a negative control and 300 μg lysate protein immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ was included as a positive control. (B) The immunoblots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with an antibody specific for Kit. These data are representative of results from more than 3 experiments.

PKCδ is associated with WT and D814Y Kit. IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit were stimulated with 100 ng/mL murine SCF for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to lysis. (A) Whole cell lysate protein (600 μg per sample) was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for Kit, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon-P, and immunoblotted with an antibody specific for PKCδ. Lysate protein (600 μg) immunoprecipitated with normal goat IgG was included as a negative control and 300 μg lysate protein immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for PKCδ was included as a positive control. (B) The immunoblots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with an antibody specific for Kit. These data are representative of results from more than 3 experiments.

Consistent with the immunoblot data, there was also serine kinase activity associated with Kit immunoprecipitates from cells expressing wild-type or mutant Kit. Of note was an increase in activity associated with D814Y Kit compared with WT Kit (data not shown). This is consistent with the coprecipitation of PKCδ with both wild-type and mutant Kit (Figure 4), as well as with the increase in total PKCδ activity (Figure 1) and membrane-associated PKCδ activity (Figure 3) in cells expressing mutant Kit. However, it is possible that this activity could represent an additional serine kinase in the Kit receptor complex.

Although PKCδ was readily detected in Kit immunoprecipitates, Kit protein was not observed in the PKCδ control immunoprecipitate (Figure 4B). Several Kit antibodies were used in these studies, however many of the commercially available antibodies recognize human Kit and are less effective at detecting murine Kit. Thus, the low sensitivity of the Kit-specific antibody in immunoblotting murine Kit probably accounts for this result.

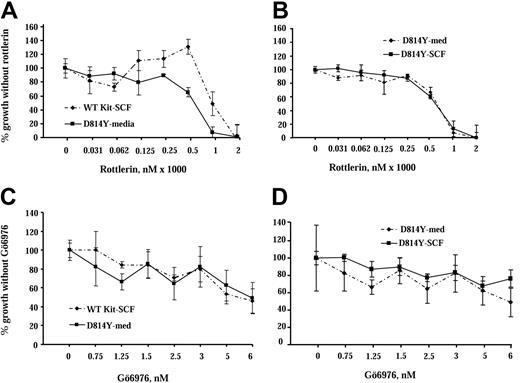

Inhibition of PKCδ has different effects on growth of IC2 cells expressing wild-type and D814Y Kit

Our study shows that PKCδ is activated by WT Kit, is constitutively active in cells expressing the Kit catalytic domain mutant, and coprecipitates with both forms of Kit. To assess the role of PKCδ in responses mediated by wild-type and mutant Kit we used rottlerin, a drug that inhibits PKCδ.34,35 IC2 cells expressing wild-type or D814Y mutant Kit were cultured in increasing concentrations of rottlerin for 72 hours and cell growth was assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation (Figure 5A). Factor-independent growth of cells expressing the D814Y Kit mutant decreased by nearly 40% in the presence of 500 nM rottlerin, while the same concentration of rottlerin increased SCF-induced growth of cells expressing WT Kit by 20%. Further, the addition of SCF did not alter the response of cells expressing D814Y Kit to rottlerin (Figure 5B). These results are consistent with PKCδ having a specific role in negative regulation of WT Kit, but possibly contributing to growth mediated by the Kit mutant. In contrast, when IC2 cells expressing wild-type or D814Y Kit were cultured in increasing concentrations of Gö6976, a PKC inhibitor selective for the α, β, and γ isoforms,35 the effect on the growth of both types of cells was essentially the same (Figure 5C). In addition, as in the rottlerin experiment, the addition of SCF did not alter the response of cells expressing D814Y Kit to Gö6976 (Figure 5D). These data suggest that PKCδ contributes to factor-independent growth mediated by the Kit catalytic domain mutant, but may be involved in negative regulation of WT Kit. These data are of particular note since the effective dose of rottlerin (500 nM) is an order of magnitude lower than the 5-μM amount reported to have nonspecific effects.36,37

Inhibition of PKCδ has different effects on growth of IC2 cells expressing WT and D814Y Kit. IC2 cells were cultured with the PKCδ selective inhibitor rottlerin or the conventional isoform PKC inhibitor Gö6976 in cell proliferation assays. (A) IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of rottlerin for 1 hour 20 minutes and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (WT Kit; ♦) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (D814Y Kit; ▪). (B) IC2 cells expressing D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of rottlerin for 1 hour 20 minutes and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (▪) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (♦). Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine and harvested after a 4-hour incubation period. Mean counts of quadruplicate samples exposed to the drug were normalized to the means of samples that were cultured without drugs. These data are representative of the results of 4 independent trials. (C) IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Gö6976 for 1 hour and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (WT Kit; ♦) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (D814Y Kit; ▪). (D) IC2 cells expressing D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Gö6976 for 1 hour and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (▪) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (♦). Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine and harvested after a 4-hour incubation period. Mean counts of quadruplicate samples exposed to the drugs were normalized to the means of samples that were cultured without drug. These data are representative of the results of 3 independent trials. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Inhibition of PKCδ has different effects on growth of IC2 cells expressing WT and D814Y Kit. IC2 cells were cultured with the PKCδ selective inhibitor rottlerin or the conventional isoform PKC inhibitor Gö6976 in cell proliferation assays. (A) IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of rottlerin for 1 hour 20 minutes and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (WT Kit; ♦) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (D814Y Kit; ▪). (B) IC2 cells expressing D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of rottlerin for 1 hour 20 minutes and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (▪) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (♦). Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine and harvested after a 4-hour incubation period. Mean counts of quadruplicate samples exposed to the drug were normalized to the means of samples that were cultured without drugs. These data are representative of the results of 4 independent trials. (C) IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Gö6976 for 1 hour and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (WT Kit; ♦) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (D814Y Kit; ▪). (D) IC2 cells expressing D814Y mutant Kit were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Gö6976 for 1 hour and then cultured for 72 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (▪) or media supplemented with 10% FBS alone (♦). Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine and harvested after a 4-hour incubation period. Mean counts of quadruplicate samples exposed to the drugs were normalized to the means of samples that were cultured without drug. These data are representative of the results of 3 independent trials. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

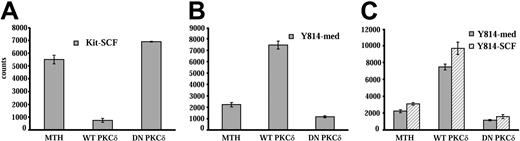

Ectopic expression of wild-type and dominant-negative PKCδ constructs has the opposite effect on growth of cells expressing WT Kit or D814Y Kit

To further define the role of PKCδ in responses mediated by WT Kit and the D814Y mutant, wild-type and dominant-negative PKCδ constructs were transiently transfected into IC2 cells expressing wild-type or mutant Kit. Transfected cells were cultured for 48 hours and growth was assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Transfection of cells expressing WT Kit with PKCδ reduced SCF-induced growth by 70%, while expression of the dominant-negative construct enhanced SCF-induced growth by 20% (Figure 6A). These results are consistent with PKCδ acting as a negative regulator of SCF-activated Kit in these cells. In contrast, expression of the wild-type PKCδ construct in cells expressing D814Y Kit enhanced factor-independent growth by 90%, while expression of the dominant-negative construct reduced factor-independent growth by nearly 50% (Figure 6B). In addition, SCF did not alter the effect of the PKCδ constructs on responses of cells expressing D814Y Kit (Figure 6C). These data, in conjunction with the results with the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin, indicate that PKCδ is a negative regulator of SCF-stimulated WT Kit and a positive regulator of growth in cells transformed by the D814Y Kit mutant.

Transfection of a PKCδ construct inhibits SCF-stimulated growth of IC2 cells expressing WT Kit, but enhances factor-independent growth of cells expressing D814Y mutant Kit. IC2 cells expressing WT Kit or the D814Y mutant were transfected with constructs coding for wild-type or dominant-negative PKCδ by electroporation. Control cells were electroporated with empty vector (MTH). (A) WT Kit transfectants were cultured for 48 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF. (B) D814Y Kit transfectants were cultured for 48 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS alone or (C) in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS (▦) and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (▧). Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine and harvested after a 6-hour incubation period. Mean counts of quadruplicate samples are shown above. These data are representative of 5 independent trials. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Transfection of a PKCδ construct inhibits SCF-stimulated growth of IC2 cells expressing WT Kit, but enhances factor-independent growth of cells expressing D814Y mutant Kit. IC2 cells expressing WT Kit or the D814Y mutant were transfected with constructs coding for wild-type or dominant-negative PKCδ by electroporation. Control cells were electroporated with empty vector (MTH). (A) WT Kit transfectants were cultured for 48 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL murine SCF. (B) D814Y Kit transfectants were cultured for 48 hours in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS alone or (C) in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS (▦) and 100 ng/mL murine SCF (▧). Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine and harvested after a 6-hour incubation period. Mean counts of quadruplicate samples are shown above. These data are representative of 5 independent trials. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

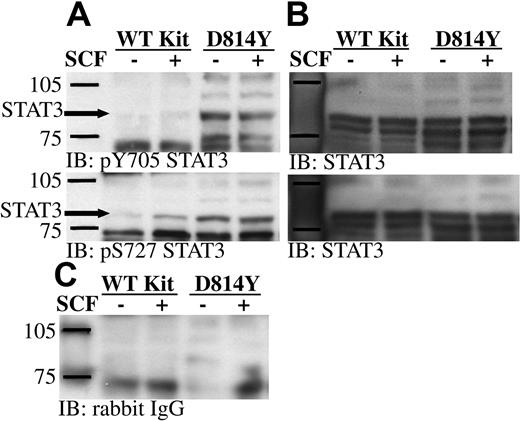

STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on Tyr705 and Ser727 in cells expressing D814Y Kit

Work by Ning et al38,39 showed constitutive DNA binding activity of STAT3 in cells expressing D816H Kit. However the upstream activating component remains to be defined. Phosphorylation of STAT3 on serine 727 is involved in the activation of this important transcription factor.40,41 PKCδ and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are 2 kinases capable of phosphorylating STAT3 on this residue. Our current findings demonstrate constitutive activation of PKCδ in cells expressing D814Y Kit. Further, previous studies from our lab have shown JNKs 1 and 2 are constitutively active in cells expressing D816V Kit.42 Therefore, we sought to determine if serine 727 of STAT3 was constitutively phosphorylated in cells expressing the Kit catalytic domain mutant. Consistent with previous studies, tyrosine 705 of the STAT3α and γ isoforms was constitutively phosphorylated in cells expressing D814Y Kit (Figure 7A).20,38,39 In addition, Figure 7A shows that serine 727 of STAT3α is also constitutively phosphorylated in cells expressing D814Y Kit. The STAT3β and γ isoforms do not contain serine 727. Some increase in serine phosphorylation of STAT3 was also noted after SCF stimulation of cells expressing WT Kit. Reprobing the membranes with an antibody specific for STAT3 demonstrated that STAT3 is expressed at equal levels by cells expressing wild-type and D814Y Kit (Figure 7B).

STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on tyrosine 705 and serine 727 in IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit. (A) Whole cell lysate protein (35 μg per lane) from IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit was run on SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon-P, and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phosphotyrosine 705 STAT3 or phosphoserine 727 STAT3. (B) Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with an antibody specific for STAT3. (C) An identical control panel was immunoblotted with normal rabbit IgG. These data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on tyrosine 705 and serine 727 in IC2 cells expressing D814Y Kit. (A) Whole cell lysate protein (35 μg per lane) from IC2 cells expressing WT or D814Y Kit was run on SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon-P, and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phosphotyrosine 705 STAT3 or phosphoserine 727 STAT3. (B) Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with an antibody specific for STAT3. (C) An identical control panel was immunoblotted with normal rabbit IgG. These data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Since both PKCδ and JNKs are activated in cells expressing the Kit catalytic domain mutant, these data raise the intriguing possibility that STAT3 is activated downstream of one of these signaling components. Studies determining if either of these kinases contributes to constitutive activation of STAT3 are in progress.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the role of PKCδ in responses mediated by wild-type and D814Y murine Kit in a murine mast cell-like line. PKCδ was activated after SCF stimulation of cells expressing WT Kit and was constitutively active in cells expressing mutant Kit (Figures 1, 3). Further, PKCδ activity was consistently higher in cells expressing D814Y Kit than cells expressing WT Kit (Figures 1, 3). This increase in kinase activity correlated with increases in tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ associated with membrane fractions (Figure 2). A positive link between tyrosine phosphorylation and PKCδ activity has been observed in some studies.32,33 This report is the first demonstration that either WT Kit or the Kit catalytic domain mutant activates PKCδ.

Although PKCδ is activated in cells expressing either wild-type or mutant Kit, we found that this serine kinase promotes growth of cells expressing D814Y Kit but inhibits growth of cells expressing WT Kit. This was illustrated in studies inhibiting PKCδ either with rottlerin or through ectopic expression of dominant-negative PKCδ constructs (Figures 5, 6). Further, overexpression of wild-type PKCδ had opposite effects on cells expressing wild-type and mutant Kit (Figure 6). In addition, SCF does not alter the effect of rottlerin or the dominant-negative PKCδ construct in cells expressing mutant Kit (Figures 5, 6).

Previous work has shown that PKCδ can have pro- or antiproliferative effects, depending upon the cell type and receptors expressed. Studies with Rat1 fibroblasts expressing the oncoprotein BCR-ABL and studies with NIH 3T3 fibroblasts expressing an oncogenic form of insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) found that PKCδ contributed to colony formation,43,44 but overexpression of PKCδ alone in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and in a human glioma cell line U-251 MG slowed cell growth.45,46 Similarly, PKCδ can have pro- or antiapoptotic functions when activated by the p60 tumor necrosis factor α receptor in human neutrophils depending on whether the cells are in suspension or adherent.47 Thus, our results and other recent data indicate that the function of PKCδ can depend on the signaling context of a given receptor. The importance of the present study is that this is the first demonstration that PKCδ function changes in response to an oncogenic mutation in a receptor.

One mechanism that could mediate the different outcome of PKCδ activation in cells expressing wild-type and mutant Kit could be changes in substrate specificity that lead to enhanced activation of one or more signaling pathways. Indeed, previous studies have suggested that phosphorylation on tyrosine alters PKCδ substrate recognition.32,48 Here we show increases in PKCδ activity and tyrosine phosphorylation in membrane fractions of cells expressing the Kit catalytic domain mutant. We also observed an increase in phosphorylation of STAT3 on serine 727, a residue known to be a target for PKCδ49,50 (Figures 2, 3, and 7). However, a variety of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase family members can also phosphorylate serine 727 of STAT3.51-54 In cells expressing the Kit catalytic domain mutant, JNKs 1 and 2 are constitutively active and could be possibilities too.42 Although extracellular signal-related kinases (Erks) 1 and 2 can also phosphorylate this residue, they are unlikely candidates in this case since they are not active in cells expressing this Kit mutant.20,39,42

PKC inhibitors show promise as potential therapeutics (reviewed in Goekjian and Jirousek55 and Swannie and Kaye56 ). PKC412, a staurosporine analog, has already progressed favorably through phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials as a single agent.57-59 This drug is a relatively selective inhibitor of the α, β, and γ isoforms of PKC, but it also inhibits several other kinases including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGF-R2), PDGF receptor (PDGFR), and Kit.55,56 Bryostatin-1 is a natural product derived from a marine organism. It activates and down-regulates PKC. Trials of bryostatin-1 suggest this drug may be useful for patients with refractory acute leukemia when combined with 1-B-D-arabinofuranosylcyotosine.60 ISIS 3521, an antisense oligonucleotide for PKCα, has demonstrated acceptable toxicity as a single agent and in combination with traditional chemotherapy drugs in phase 1 trials.61-63 ISIS 3521 in combination with chemotherapy has been most promising in patients with non–small cell lung cancer, and large phase 3 trials are currently under way.64

The introduction of inhibitors specific to other PKC isoforms, particularly PKCδ, may advance treatment of hematologic disease since PKCδ has been associated with several hematologic malignancies. Indeed, the present work suggests that PKCδ may be a therapeutic target in mastocytosis or AML associated with mutations in the catalytic domain of Kit. Other recent work has linked PKCδ expression to B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia,28 multiple myeloma,29 and inappropriate survival of neutrophils,47 which occurs in inflammatory diseases. PKCδ inhibitors offer the possibility of a novel therapy with potentially less toxicity than traditional chemotherapy since PKC412 and ISIS 3521 have been well tolerated. PKCδ inhibitors likely have greatest potential in conjunction with traditional chemotherapy or as part of a cocktail targeting several signal transduction components. The potential benefits of a cocktail approach over a monotherapeutic approach are supported by reports that chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and GIST patients acquire resistance to STI571/imatinib over time.65-67 Thus, simultaneous targeting of a gain-of-function mutant receptor and its downstream signaling pathways may ultimately be the most effective treatment strategy. Since Kit catalytic domain mutants are resistant to STI571/imatinib, studies are under way to define direct inhibitors of this type of Kit mutant that could be combined with inhibitors of PKCδ.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 12, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1450.

Supported in part by the NCI under contract NO1-CO-12400 with Science Applications International (SAIC)–Frederick.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr Shivakrupa, Dr Johan Lennartsson, Dr Alan Bernstein, and Dr Doug Lowy for critical reading of this manuscript and helpful discussions. We also thank Dr Bernstein for providing the IC2 cell lines infected with wild-type and mutant Kit as well as Dr Peter Blumberg for kindly providing the PKCδ constructs.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.