Comment on Boles et al, page 779

Cancer cells easily triumph over the body's defenses. Gene fusion, gene amplification, and gene silencing promote tumor survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis. Escape from immune surveillance adds another piece to the cancer puzzle.

Mother Nature has revealed few clues that support the notion that common human cancers pay attention to the immune system. Natural killer group 2D (NKG2D) is a c-lectin–like receptor on the surface of human natural killer (NK) cells, γδ T cells, and αβ CD8+ T cells that, when engaged by its ligands, can activate a killer program. In 2002, Groh and colleagues1 showed that a variety of common human cancers express ligands for NKG2D collectively called MHC class I chain related (MIC), which are not expressed on most normal tissues. MIC+ tumors shed soluble MIC into the bloodstream, resulting in NKG2D endocytosis and marked reduction of its surface expression on large numbers of tumor-infiltrating and blood T cells, which severely impairs their responsiveness to tumor antigens.1 When a tumor sheds a ligand that naturally binds to and down-modulates a killer cell's triggering receptor, Mother Nature is speaking loud and clear: certain tumors are evading the immune system, not by avoiding immune recognition but rather by using it to their advantage.FIG1

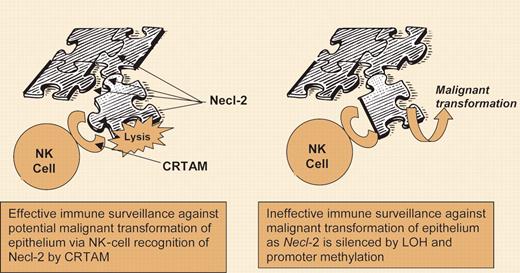

In the current issue of Blood, Boles and colleagues discover a new receptor-ligand story that sheds light on how a common human tumor, this time lung cancer, has evolved yet another mechanism to evade the cytotoxic arm of the immune system. Loss of heterozygosity plus gene methylation silences tumor suppressor in lung cancer-1, or TSLC1, that encodes a cell-surface protein called Necl-2. Necl-2 belongs to a family of nectin-like molecules required for cell-to-cell adhesion in ordered epithelial-cell growth. The absence of Necl-2 likely contributes to loss of cell polarity and cell-to-cell adhesion during neoplastic transformation and metastasis. Boles and colleagues have uncovered yet another very important reason for Necl-2 to be silenced in cancer: it serves as the ligand for a receptor only expressed on activated NK cells and CD8+ T cells. The receptor, known as class I–restricted T-cell–associated molecule, or CRTAM, is abundantly unregulated on NK cells following activation of specific receptors (eg, CD16 or NKp30) or following incubation with NK tumor-cell targets such as K562. Likewise, engagement of CD3, which might occur in T-cell recognition of a tumor antigen, up-regulates CRTAM in CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). In a series of elegant experiments, these researchers show that engagement of CRTAM by Necl-2 promotes cytotoxicity by NK cells and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) secretion by CD8+ CTLs. Importantly, they also demonstrate that when Necl-2 is expressed by tumor cells, NK cells are responsible for inhibiting tumor growth in vivo.

But if Necl-2 is expressed on normal lung epithelial cells, one might ask why nonneoplastic lung tissue is not a target of NK-cell lysis. First, CRTAM is not expressed on resting human NK or T cells, and the mechanism for its expression appears to be tightly regulated. Second, through homotypic and heterotypic binding required for normal cell adhesion and ordered growth, the epitopes of Necl-2 recognized by CRTAM are likely not exposed. Regardless, the discovery by Boles and colleagues adds to the growing body of evidence in support of immune surveillance for control of common cancers. Conceivably, pharmacologic induction of tumor suppressor genes silenced by methylation, as is currently being explored for treatment of cancer, may result in cell-surface alterations that substantially weaken immune escape. ▪