Comment on Hill et al, page 2559

Previous optimism about the complement inhibitor eculizumab as a treatment for hemolytic paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is sustained with a report in this issue of Blood by Hill and colleagues.

In 1938, Jordan,1 Dacie et al,2 and Ham3 demonstrated, almost simultaneously, that serum complement is responsible for the lysis of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) red cells. In the next 67 years, numerous laboratories systematically explored the molecular, cellular, and biochemical pathways accountable for hemolysis in PNH. PNH is an acquired hemolytic anemia caused by the expansion of a clone that has acquired a mutation in the PIGA gene essential in the biosynthesis of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors. Consequently, blood cells derived from the mutant clone are deficient in all GPI-anchored proteins. The classic clinical features of PNH are due to intravascular hemolysis, cytopenia, and thrombophilia. While intravascular hemolysis and thrombosis occur with the expansion of the abnormal clone, cytopenia often pre-exists and is due to underlying bone marrow failure. Two of the missing proteins on PNH blood cells, CD55 and CD59, are complement regulatory proteins protecting the cell from complement lysis. The lack of these 2 proteins accounts for the increased sensitivity of PNH red cells to lysis by complement. Complement is the immune system's first line of defense to eliminate foreign and harmful pathogens. It is a blood-based system composed of a series of enzymes and precursors that interact with each other in a series of all-or-none steps that ultimately leads to the lysis of the pathogen (see figure). Knowledge of the pathway responsible sets the stage for the development of a targeted therapy for hemolysis in PNH. Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody binding the C5 complement protein and blocking the hemolytic activity of serum. In a first open-label pilot study in patients with hemolytic PNH the complement inhibitor resulted in an impressive reduction of intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, and transfusion requirement.4 The investigators now show in a 52-week extension study of the 11 patients receiving eculizumab that continuous treatment with the complement inhibitory antibody upholds the dramatic reduction of intravascular hemolysis as demonstrated by the maintenance of low levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The decrease in hemolysis leads to a decrease in transfusion requirement, a decreased frequency of hemoglobinuria episodes, and, most rewardingly, to a significant improvement in quality of life. During the study eculizumab continued to be safe and was well tolerated by all study participants. Complement is not responsible for the underlying bone marrow failure; not surprisingly, therefore, eculizumab showed no effect on cytopenia in patients with PNH. The pathogenesis of thrombosis, which is the major cause of death in patients with PNH, is not understood. The effect of eculizumab on the risk of thrombosis remains to be determined in studies including more patients with a longer follow-up. Long-term studies will also be necessary to determine possible adverse effects caused by long-term complement inhibition. Complement inhibition is not a cure for PNH. The abnormal cell clone persists necessitating sustained treatment and disease surveillance. However, for PNH patients with symptoms of hemolysis, which may be debilitating and otherwise difficult to treat, complement inhibition promises to become the future treatment of choice.

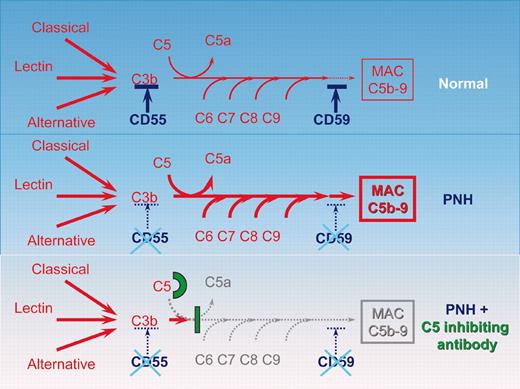

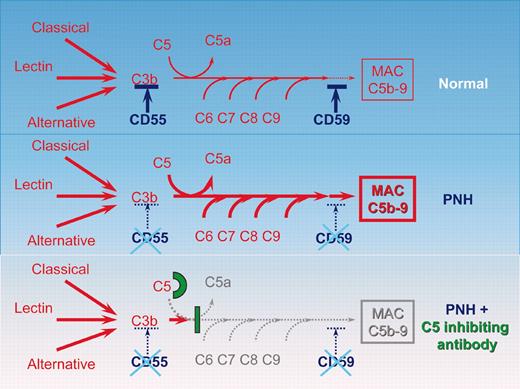

Schematic representation of the complement cascade reaction in healthy individuals, in patients with PNH, and in patients with PNH receiving the C5-inhibiting antibody. In humans the complement system consists of more than 30 plasma and cell-surface proteins. The complement system may be activated by 3 different pathways: the classic, lectin, and alternative pathways. The primary goal of the activation pathway is C3b deposition on the target cell, which is followed by the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) in the lytic pathway of complement activation, necessary for the lysis of the target. The deficiency of the surface proteins CD55 and CD59 leads to the uncontrolled lysis of PNH red cells by complement. The C5-binding antibody eculizumab blocks the lytic pathway of complement activation.

Schematic representation of the complement cascade reaction in healthy individuals, in patients with PNH, and in patients with PNH receiving the C5-inhibiting antibody. In humans the complement system consists of more than 30 plasma and cell-surface proteins. The complement system may be activated by 3 different pathways: the classic, lectin, and alternative pathways. The primary goal of the activation pathway is C3b deposition on the target cell, which is followed by the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) in the lytic pathway of complement activation, necessary for the lysis of the target. The deficiency of the surface proteins CD55 and CD59 leads to the uncontrolled lysis of PNH red cells by complement. The C5-binding antibody eculizumab blocks the lytic pathway of complement activation.

I thank P.J. Mason for interesting discussions. ▪