Abstract

CREB-binding protein (CBP) and its para-log p300 are transcriptional coactivators that physically or functionally interact with over 320 mammalian and viral proteins, including 36 that are essential for B cells in mice. CBP and p300 are generally considered limiting for transcription, yet their roles in adult cell lineages are largely unknown since homozygous null mutations in either gene or compound heterozygosity cause early embryonic lethality in mice. We tested the hypotheses that CBP and p300 are limiting and that each has unique properties in B cells, by using mice with Cre/LoxP conditional knockout alleles for CBP (CBPflox) and p300 (p300flox), which carry CD19Cre that initiates floxed gene recombination at the pro–B-cell stage. CD19Cre-mediated loss of CBP or p300 led to surprisingly modest deficits in B-cell numbers, whereas inactivation of both genes was not tolerated by peripheral B cells. There was a moderate decrease in B-cell receptor (BCR)–responsive gene expression in CBP or p300 homozygous null B cells, suggesting that CBP and p300 are essential for this signaling pathway that is crucial for B-cell homeostasis. These results indicate that individually CBP and p300 are partially limiting beyond the pro-B-cell stage and that other coactivators in B cells cannot replace their combined loss.

Introduction

CBP (Crebbp) and p300 (Ep300) are highly related, large (∼265 kDa) nuclear proteins that function as coactivators and cofactors for an ever-increasing number of transcriptional regulators and other proteins in vitro. They enhance transcription (hence “coactivate”) predominantly through binding to the activation domains of transcription factors via specific protein-binding domains that are unique to this 2-member family of proteins. It is believed that this positions the adaptor, protein acetyltransferase, and ubiquitin ligase functions of CBP and p300 at gene promoters and enhancers in order to potentiate transcription.1 The necessity of CBP and p300 for the expression of endogenous genes has mostly been unexplored, however.

Over the last decade, the number of interacting partners for CBP and p300 has grown over a hundred-fold so that these coactivators could now be considered the most heavily connected nodes in the known mammalian protein-protein interaction network.2-4 Over 60 transcription factors and other proteins essential for lymphocyte development and function in mice are included among the more than 320 described CBP and p300 interaction partners.3,5 Of these, 36 are required for B cells (Table 1). The “high connectivity” of CBP and p300 as nodes in transcriptional regulatory networks signifies that they may be present in limiting quantities. Several studies indicate that this may be the case.9,31 The in vivo evidence is compelling, as mice that are doubly heterozygous for CBP and p300 null alleles die during early embryogenesis, and mice and humans that are haploinsufficient for CBP have severe developmental defects.31,32

CBP and p300 have been implicated in the activities of numerous B-cell–critical transcription factors such as NF-κB, PU.1, E47, EBF, and Pax5 (Table 1).33 B cells originate in the bone marrow where hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) produce multilineage progenitors that yield the first B-lineage–committed stage (pro-B), which then develop stepwise through the pre-B and immature B-cell stages before exiting the bone marrow to become transitional T1 and T2 immature B cells in the spleen, where maturation is completed.34 In this regard, CBP–/– mouse embryos have defective hematopoiesis,35 as do chimeric mice generated using CBP or p300 null embryonic stem cells,36 but the effects of the mutations appear to be at the level of the HSC. CBP+/– mice have approximately 3-fold fewer B cells as a percentage of peripheral blood cells, whereas T cells are normal, although the B-cell phenotype is statistically significant only if splenomegaly is present.37 Conversely, others have reported equivalent percentages of T cells and B cells in the spleens of CBP+/– mice.38 Additional studies have shown that CBP can have a tumor suppressor role in hematopoietic lineages, including T cells39 and possibly the B-cell lineage (plasmacytomas developed in mice that received transplants of CBP+/– cells).37 Interestingly, mice homozygous for mutations in the CREB- and c-Myb–binding domain (KIX) of p300 have a B-cell deficiency included in a multilineage defect in hematopoiesis.40 It is uncertain, however, if CBP and p300 are essential for B-cell development and function after commitment of progenitor cells to the B-cell lineage. To address the roles of CBP and p300 in these processes, we induced the inactivation of CBPflox and p300flox alleles in CD19Cre mice that begin to express Cre recombinase at the pro-B-cell stage.

Materials and methods

Mice

The p300flox allele was constructed by flanking exon 9 of the mouse Ep300 gene with LoxP sites.3 CBPflox and CD19Cre mice were described previously.39,41 The recombined null alleles are designated p300Δflox and CBPΔflox. Relevant alleles in control and mutant mice are wild type unless specified otherwise. Most experiments used mice maintained on a C57BL/6 background, except that Mx-Cre mice were maintained on BALB/c.

Genotyping of mice

Recombination of the LoxP sites flanking p300 exon 9 in cells expressing Cre was determined by Southern blot using an EcoRI digest and a cDNA probe to the region encoding amino acids (aa's) 615-681 or by semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers p4, CTCTACATCCTAAGTGCTAGG; p5, TGGACTGGTTATCGGTTCACC; and p6, CAGTAGATGCTAGAGAAAGCC, producing a 540-bp wild-type band, a 720-bp p300 flox band, and a 1.1-kb p300 Δflox band. This semiquantitative PCR overestimates the deletion of p300flox that can be corrected by using a standard curve of samples of known deletion as determined by Southern blot. PCR genotyping for the CBPflox allele was previously reported.39 Detection of the CBPflox and CBPΔflox alleles by Southern blot was performed using an EcoRI digest and a 5′ external probe.

B-cell purification

Magnetic beads from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA) were used for positive (B220 microbeads, 130-049-501) and negative (B-cell isolation kit, 130-090-862) selection. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) purification of B-cells was performed as indicated.

Indirect immunofluorescent and Western blots

Antibodies against CBP (A-22 and C-20) and p300 (N-15 and C-20) for immunofluorescence (IF) and Western blotting were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). IF was performed essentially as described using splenic B cells purified by negative selection and C-terminal–specific p300 (1:800 dilution, C-20) and CBP (1:800, C-20) antibodies.3,39 After immunostaining, cells were viewed under a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a 40 ×/0.95 objective lens and a Nikon DMX1200 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were recorded with Nikon ACT-1 software; Adobe Photoshop 5.0 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) was used to process images. Western blots using boiled SDS whole-cell lysates from purified splenic B cells were performed as previously described using cocktails of CBP (A-22 and C-20) or p300 antibodies (N-15 and C-20).40

ELISA assays

Serum samples were collected from 3- to 6-month-old mice. Relative immunoglobulin levels (absorbance at 405 nm) were measured by enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL).

Microarray

Affymetrix U74Av2 microarray chips (12 488 probe sets; Santa Clara, CA) were used to test RNA isolated from unstimulated splenic B220+ B cells purified by magnetic bead–positive selection. Spotfire software version 8.1 (Cambridge, MA) was used for data analysis.

Flow cytometry and complete blood count

Bone marrow, spleen, and lymph node cells obtained from 6- to 10-week-old control and mutant littermate mice were made into single-cell suspensions in PBS supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated FBS. Cells were stained with a combination of fluorescence-conjugated antibodies (anti-B220, anti-CD43, anti-IgM, anti-CD3, anti-IgD, anti-CD21, or anti-CD23; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and applied to a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson). Data were collected and analyzed by using CellQuest 3.3 software (Becton Dickinson). Automated complete blood counts (CBCs) were performed using a Hemavet 3700R (CDC Technologies, Oxford, CT).

B-cell culture and B-cell receptor (BCR) stimulation

Splenic B220+ cells purified by FACS from 6- to 8-week-old littermate mice were cultured in IMDM medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.25% Pluronic F-68, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin for 16 hours and treated with 30 μg/mL of soluble anti-IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Bar Harbor, ME) for 4 hours. Cells were harvested and total RNA was purified using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

RT-qPCR

cDNA was generated from 500 ng total RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on an Opticon DNA Engine (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) using Qiagen (Valencia, CA) SYBR Green PCR master mix. qPCR primers (sequences available upon request) were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and only pairs with sense and antisense primers on different exons were chosen for RT-qPCR analysis. A single product for each primer pair was further confirmed by gel and melt-curve analysis. mRNA level for each gene was normalized to β-actin. Relative expression was calculated by normalizing to the lowest value for an experiment; this permits combining data from multiple experiments. BCR-dependent expression was determined by subtracting the expression for mock-treated cells from anti-IgM–treated cells.

Results

Inactivation of CBPflox and p300flox conditional alleles in mouse B cells

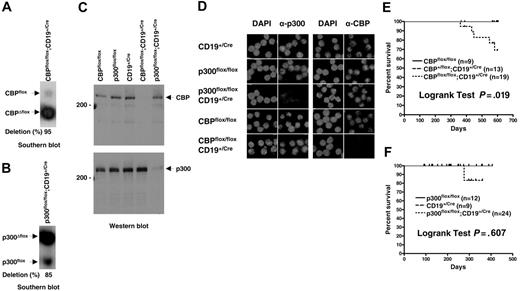

The p300flox allele contains LoxP sites in the 2 introns flanking the exon encoding aa's 588-626, which is part of the conserved CREB-binding domain (KIX)3 ; the equivalent exon is targeted in CBPflox and constitutes a comparable experimental system.39 Cre-recombinase–mediated deletion of the intronic and exonic sequences yielding CBPΔflox and p300Δflox null alleles was achieved using a CD19Cre gene that is expressed throughout B-cell development starting at the pro-B stage.41 The CD19Cre mutant allele contains a Cre recombinase cDNA insertion that inactivates CD19, necessitating its use in the heterozygous state. CBPflox/flox; CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice efficiently recombined the floxed genes as determined by quantitative Southern blot of splenic B-cell DNA (typically 70%-95%; Figure 1A-B). Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for the N- and C-termini of CBP or p300 confirmed the loss of both proteins in B-cell lysates (Figure 1C), as did indirect immunofluorescence using C-terminal–specific antibodies for CBP or p300 on purified B cells (Figure 1D). There was no apparent increase in the levels of wild-type CBP or p300 protein in Δflox mutant B cells, indicating that compensation by increased expression is unlikely (Figure 1C).

Efficient inactivation of CBPflox or p300flox in mouse B cells does not result in lymphoma. Quantitative Southern blot of genomic DNA isolated from purified splenic B cells for CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (A) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (B) mice. Nonrecombined (flox) alleles, recombined (Δflox) alleles, and percent deletion are indicated. (C) Western blot of cell lysates from purified splenic B cells using CBP-specific (top panel) and p300-specific (bottom panel) antisera. Genotypes, 200-kDa markers, and position of CBP and p300 are indicated. (D) Indirect immunofluorescence of control and CBP and p300 null purified splenic B cells using CBP- and p300-specific antisera. Genotypes are indicated. Nuclear DNA stained with DAPI. Survival curves for CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (E) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (F) and control mice. Age of mice (days) and percent surviving are indicated. Tick marks indicate mice that were censured (killed for experimentation) or still alive at the end of the study. Curve comparisons by 2-tailed log-rank test, number of mice of each genotype, and P values are indicated.

Efficient inactivation of CBPflox or p300flox in mouse B cells does not result in lymphoma. Quantitative Southern blot of genomic DNA isolated from purified splenic B cells for CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (A) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (B) mice. Nonrecombined (flox) alleles, recombined (Δflox) alleles, and percent deletion are indicated. (C) Western blot of cell lysates from purified splenic B cells using CBP-specific (top panel) and p300-specific (bottom panel) antisera. Genotypes, 200-kDa markers, and position of CBP and p300 are indicated. (D) Indirect immunofluorescence of control and CBP and p300 null purified splenic B cells using CBP- and p300-specific antisera. Genotypes are indicated. Nuclear DNA stained with DAPI. Survival curves for CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (E) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (F) and control mice. Age of mice (days) and percent surviving are indicated. Tick marks indicate mice that were censured (killed for experimentation) or still alive at the end of the study. Curve comparisons by 2-tailed log-rank test, number of mice of each genotype, and P values are indicated.

Increased occurrence of premature death in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice but loss of CBP or p300 does not lead to B-cell tumors

CBP and p300 have been identified as tumor suppressors in the myeloid and lymphoid lineages of mice.36,37,39 In humans, CBP and p300 translocations occur in leukemia and somatic mutations have been found in solid tumors.42 We tested whether loss of CBP specifically in lineage-committed cells results in B-cell malignancy and whether loss of p300 in B cells leads to tumors. CBPflox/flox; CD19+/Cre mice on a mixed genetic background appeared generally healthy but had an increased incidence of death after about one year when compared with CBPflox/flox and CBP+/flox;CD19+/Cre littermate controls (Figure 1E; P = .019, log-rank test, n = 9-19). The cause of death was undetermined but there were no instances of B-cell lymphoma. The p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice also appeared healthy and had lifespans that were not significantly different from control mice out to one year of age (Figure 1F; P = .606, log-rank test, n = 9-24). It is possible that p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice will show increased rates of death after one year like CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice, but we have not observed any incidence of lymphoma. We conclude therefore that CBP and p300 do not have highly essential tumor suppressor functions in B cells after the pro-B stage of development.

Modest reduction in peripheral B cells in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice

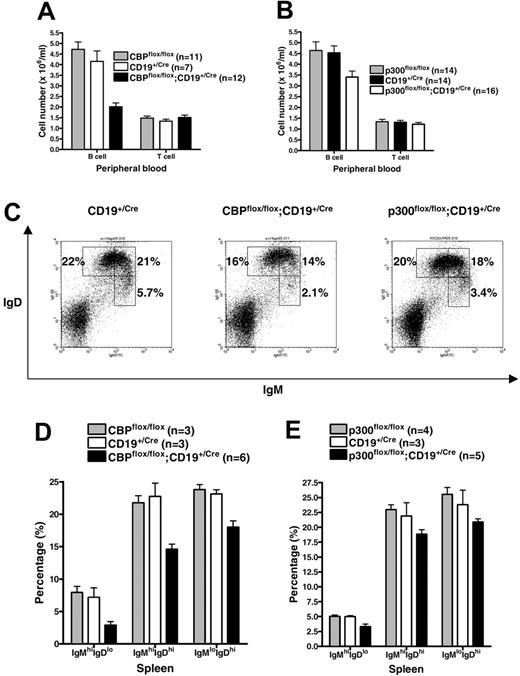

We observed an approximately 50% decrease in the number of B cells in the peripheral blood of CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice compared with CBPflox/flox and CD19+/Cre controls (Figure 2A; analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < .001, n = 7-12). A similar decrease was observed in the spleen and lymph nodes (W.X., data not shown). The p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice showed only an approximately 25% decrease in peripheral B cells in the blood (Figure 2B; ANOVA, P = .02, n = 14-16), spleen, and lymph nodes (W.X., data not shown). T-cell numbers were not disturbed in either mutant, as expected (Figure 2A-B). Flow cytometric analysis of splenic B cells revealed similarly modest decreases in the proportions of all 3 major IgM+ and IgD+ B-cell classes in CBPflox/flox; CD19+/Cre mice: IgMhi IgDlo cells include mature marginal zone (MZ) and B-1 B cells as well as T1 immature B cells; IgMhi IgDhi includes T2 immature B cells and proliferating B cells; and IgMlo IgDhi includes follicular mature (FM) B cells (Figure 2C-D). IgMhi IgDlo B cells were the most affected proportionally (2-to 3-fold lower, P = .004, ANOVA), but examination by IgM and CD21 staining did not reveal a disproportionate loss of IgMhi CD21lo T1 cells (W.X., data not shown). IgM and IgD staining of p300flox/flox; CD19+/Cre splenic B cells showed a similar, albeit more modest, phenotype (Figure 2C,E). Together, these results demonstrate that B cells lacking CBP or p300 can still efficiently populate the lymphoid organs, with only a modest reduction in total cell numbers.

Modest deficit in peripheral B cells of CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. The number of B cells and T cells per mL of peripheral blood for CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (A) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (B) mice and controls. Number of mice of each genotype is indicated. Mean ± SEM. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis using anti-IgM and anti-IgD antibodies and splenic lymphocytes from CD19+/Cre, CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre, and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. Percentage of total splenic lymphocytes representing the major B-cell subtypes (IgMhi IgDlo, IgMhi IgDhi, IgMlo IgDhi). (D-E) Quantification of IgM and IgD flow cytometry data as in panel C for the indicated number of mice of each genotype (mean ± SEM). Flow cytometric analysis and complete blood count analyses for the CBPflox and p300flox groups were performed at different times and may not be directly comparable to each other.

Modest deficit in peripheral B cells of CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. The number of B cells and T cells per mL of peripheral blood for CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (A) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (B) mice and controls. Number of mice of each genotype is indicated. Mean ± SEM. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis using anti-IgM and anti-IgD antibodies and splenic lymphocytes from CD19+/Cre, CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre, and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. Percentage of total splenic lymphocytes representing the major B-cell subtypes (IgMhi IgDlo, IgMhi IgDhi, IgMlo IgDhi). (D-E) Quantification of IgM and IgD flow cytometry data as in panel C for the indicated number of mice of each genotype (mean ± SEM). Flow cytometric analysis and complete blood count analyses for the CBPflox and p300flox groups were performed at different times and may not be directly comparable to each other.

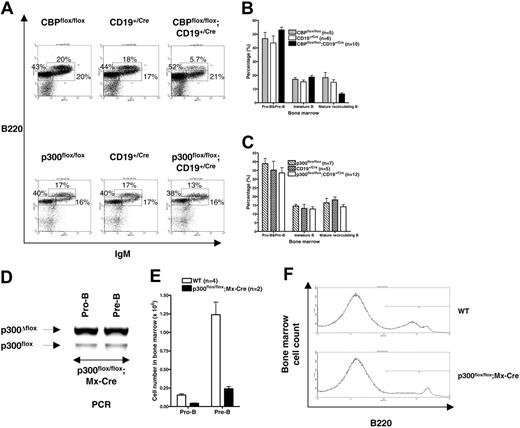

B-cell development in the bone marrow proceeds without obvious blockage in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice

We did not detect significant alterations in the proportions of the pro-B, pre-B, and immature stages of B-cell development in the bone marrow of CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. B220 and IgM staining revealed proportions of B220lo IgM– pro- and pre-B cells and B220int IgM+ immature B cells that were not significantly different between mutant and control mice (Figure 3A-C). The fraction of B220hi IgM+ mature recirculating B cells was approximately 2-fold lower in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (Figure 3B; P < .001, ANOVA) but not p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice (Figure 3C; P = .322, ANOVA). Staining for B220 and CD43 also revealed that the proportions of B220lo CD43+ (pro-B) and B220lo-int CD43– (pre-B and immature B cells) were unaffected in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice (W.X., data not shown). Interestingly, there was a decrease in the mean fluorescence intensity for surface B220 in pre-B and immature B cells, but not mature B cells, from CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre but not p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice (Figure S1, available at the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). This correlated with a reduction in the level of B220 mRNA, indicating that the expression of this isoform produced from the CD45 protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor gene is dependent on CBP in B-cell progenitors (Figure S1). CD45 null mice have a decreased percentage of mature B cells in the bone marrow,43 as do CBPflox/flox; CD19+/Cre mice (Figure 3B), suggesting that reduced expression of B220 may contribute to the phenotype of the latter.

Loss of p300 before B-lineage commitment compromises B-cell development

We previously showed that a mutation in the CREB- and c-Myb–binding KIX domain of p300 causes multilineage defects in hematopoiesis that include B-cell deficiency in mice.40 We were therefore surprised that the loss of p300 did not cause a similar B-cell deficiency in p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. This inconsistency may indicate that p300 (ie, the p300 KIX domain) is necessary for B cells before, or at, the pro-B stage of development when CD19Cre begins expression. We tested this prediction by using mice with the interferon-inducible Mx-Cre transgene that express Cre efficiently in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) following treatment of the mice with double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). The number of pro-B- and pre–B-cell progenitors in the bone marrow was examined in wild-type and p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mice 6 months after injection of dsRNA. The 6-month delay ensured that any effects of interferon on B cells had subsided and that B-cell progenitors have been replaced by new cells originating from HSCs (mature peripheral B cells may not have turned over, however44 ). The p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mice with efficient deletion of p300flox in pro-B and pre-B cells had 3.5-fold fewer pro-B cells and 5-fold fewer pre-B cells in the bone marrow compared with wild-type mice (n = 2-4; Figure 3D-E). B220 flow cytometric analysis also emphasized the deficiency of B cells in the bone marrow of p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mice (Figure 3F). Overall, these findings support the model that p300 is more important for B-cell development before, or at, the pro-B stage, rather than later.

Proportions of B-cell progenitors in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice are normal but p300 is essential before or during the pro-B stage. (A) Representative B220 and IgM flow cytometric analyses of lymphocyte gated bone marrow cells from the indicated mouse genotypes. Percentage of each major subtype is indicated. (B-C) Quantification of bone marrow B-cell progenitors by B220 and IgM flow cytometry as in panel A. Pro-B and pre-B cells (B220lo IgM–), immature B cells (B220int IgM+), and mature recirculating B cells (B220hi IgM+). Number of mice of each genotype is indicated. Mean ± SEM. (D) Recombination of the p300flox allele in FACS-purified pro-B (B220+ CD43+ IgM–) and pre-B (B220+ CD43–IgM–) cells from a representative p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mouse with efficient deletion 6 months after inducing Cre expression with dsRNA. (E) Number of pro-B and pre-B cells in dsRNA-treated wild-type (WT; n = 4) and p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mice (n = 2) as in panel D (mean ± SEM). (F) Representative histogram showing B220+ bone marrow cells as in panels D-E.

Proportions of B-cell progenitors in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice are normal but p300 is essential before or during the pro-B stage. (A) Representative B220 and IgM flow cytometric analyses of lymphocyte gated bone marrow cells from the indicated mouse genotypes. Percentage of each major subtype is indicated. (B-C) Quantification of bone marrow B-cell progenitors by B220 and IgM flow cytometry as in panel A. Pro-B and pre-B cells (B220lo IgM–), immature B cells (B220int IgM+), and mature recirculating B cells (B220hi IgM+). Number of mice of each genotype is indicated. Mean ± SEM. (D) Recombination of the p300flox allele in FACS-purified pro-B (B220+ CD43+ IgM–) and pre-B (B220+ CD43–IgM–) cells from a representative p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mouse with efficient deletion 6 months after inducing Cre expression with dsRNA. (E) Number of pro-B and pre-B cells in dsRNA-treated wild-type (WT; n = 4) and p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mice (n = 2) as in panel D (mean ± SEM). (F) Representative histogram showing B220+ bone marrow cells as in panels D-E.

Slightly increased serum IgM and IgG3 levels in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice

We next tested a crucial parameter of B-cell function by measuring serum immunoglobulin levels in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice. When compared with CBPflox/flox and CBP+/flox;CD19+/Cre controls, the relative levels of IgG3 (P = .007, ANOVA, n = 14-16) and IgM (P = .003, ANOVA, n = 14-16) were increased approximately 2-fold in CBPflox/flox; CD19+/Cre mice. The p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice had normal amounts of IgG3 and IgM, and levels of IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgA, Igκ, and Igλ were comparable between controls and both mutants (W.X., data not shown). We next inquired if marginal zone B cells were increased in the spleens of CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice, as they tend to secrete greater amounts of IgM and IgG3, but there were no significant differences in proportions of marginal zone (B220+ CD21hi CD23lo), follicular (B220+ CD21int CD23hi), and newly formed (B220+ CD21lo CD23lo) B cells between control and mutant mice (D.W. and W.X., data not shown). Although untested here, Notch signaling may be defective in CBP null B cells, as loss of the Notch-responsive factor RBP-J reportedly leads to approximately 3-fold higher levels of IgG3.45

Resting CBP null B cells have nominal changes in global gene expression

We next tested if widespread alterations in gene expression would occur in B cells lacking a global coactivator such as CBP. Affymetrix microarrays were used to test RNA isolated from unstimulated purified splenic B cells. Unexpectedly, we found that global gene expression in B cells from CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice (deletion frequency ∼80%-85% confirmed by semiquantitative PCR, not shown, n = 2) was largely unperturbed compared with CBPflox/flox (n = 2) and CBP+/flox;CD19+/Cre controls (n = 2). Only 59 probe sets were downregulated more than 1.7-fold in CBP null B cells compared with controls in a statistically significant manner (Table 2; 2.6 ± 1.9-fold, mean ± SD, P < .05, t test). Another 30 probe sets were upregulated 1.7-fold or more (2.2 ± 0.6-fold, P < .05; Table S1). Thus, only 89 (1.3%) of 6651 probe sets (omitting probe sets with unreliable signals in all 6 samples) were more than 1.7-fold different in the mutants and statistically significant. As these criteria are not highly stringent, some of the differences observed in the mutants could have occurred by chance. Therefore, most genes were not measurably disturbed in resting CBP null B cells, although a few potential outliers are worth noting. Genes with reduced expression (∼2- to 3-fold) in the mutant arrays include effectors (eg, Ig kappa and heavy chains, Ccr7) and transcriptional regulators with roles in B cells (eg, C2ta, Ets1, Relb). Transcriptional cofactors (eg, Mcm2 and Smarca3) that are upregulated may hint at compensatory mechanisms for loss of CBP.

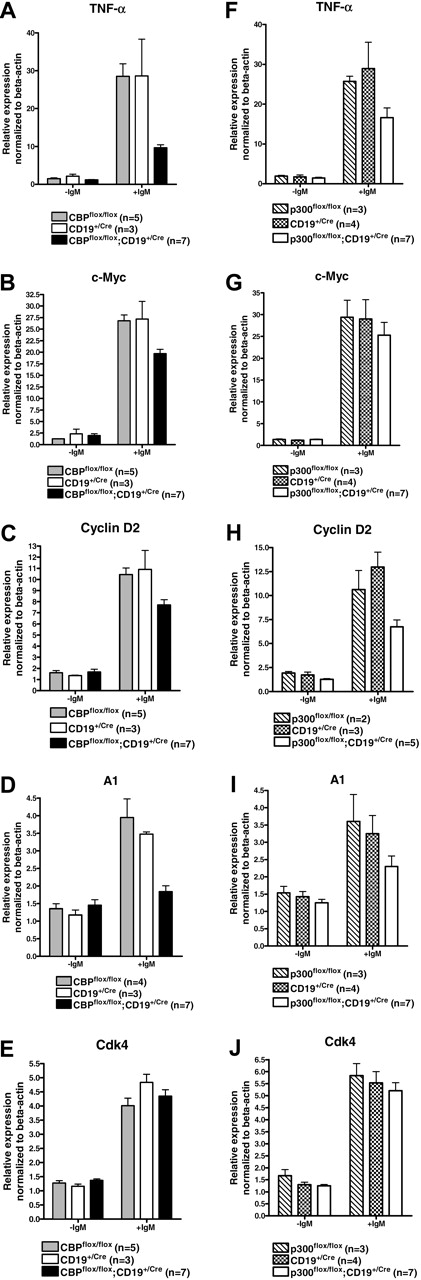

Attenuated BCR-responsive gene expression in CBP and p300 null B cells

BCR-signaling–responsive gene transcription has a central role in maintaining B-cell homeostasis and is thought to principally involve several CBP/p300 interacting transcription factors that include NF-κB and NF-AT. We tested if CBP or p300 was limiting for BCR-inducible target genes using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) to measure mRNA from FACS-purified splenic B cells following 4-hour stimulation with anti-IgM ex vivo. Test gene expression was normalized to β-actin mRNA. Efficient recombination (typically ∼80%-90%) of the CBPflox and p300flox alleles was confirmed by PCR (W.X., data not shown). We tested 5 BCR-inducible genes that represent putative CBP/p300 target genes and play roles in B-cell biology: tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; Tnf), c-Myc (Myc), Bcl2-related protein A1a (A1, Bfl-1; Bcl2a1a), cyclin D2 (Ccnd2), and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4). TNF-α is regulated in lymphocytes by the CBP/p300 interacting factors ATF2, Jun, and NF-AT and has reduced expression in T cells with CBP haploinsufficiency.38,46 BCR-dependent TNF-α expression was reduced approximately 68% in CBP null B cells (P = .002, one-tailed ANOVA) and approximately 40% in p300 null B cells compared with controls (P = .044; Figure 4A,F). A comparable deficit in TNF-α expression was observed in CBP null follicular and marginal zone splenic B cells, indicating that the defect is not specific for a particular B-cell subtype (W.X., data not shown). The role of TNF-α in B cells is unclear but it may act as an autocrine growth factor, suggesting that reduced expression may affect B-cell homeostasis.47,48 c-Myc expression in B cells requires the CBP/p300 interacting factor NF-κB,49 and BCR-dependent expression was reduced approximately 30% in CBP null cells (P = .004) but only approximately 14% in p300 null B cells (P = 0.33; Figure 4B,G). c-Myc is highly essential in B cells, suggesting that modestly reduced levels may be detrimental in conjunction with reductions in other essential factors.50 Cyclin D2 is an NF-κB target that is limiting for BCR-dependent B-cell proliferation51,52 and its BCR-dependent expression was reduced approximately 34% in CBP null cells (P = .01) and approximately 44% in p300 null B cells (P = .008; Figure 4C,H). Another NF-κB target is A1, an antiapoptotic Bcl2 family member thought to have a role in BCR-mediated B-cell survival.51 BCR-inducible expression of A1 was markedly reduced by approximately 84% in CBP null cells (P < .001) and approximately 46% in p300 null B cells (P = .075; Figure 4D,I). Not all tested genes were affected by the loss of CBP or p300, however, as the E2F target Cdk4 showed normal BCR-inducible expression in both mutants53 (Figure 4E,J). Together, these results indicate that CBP and p300 are generally limiting for BCR-dependent transcription.

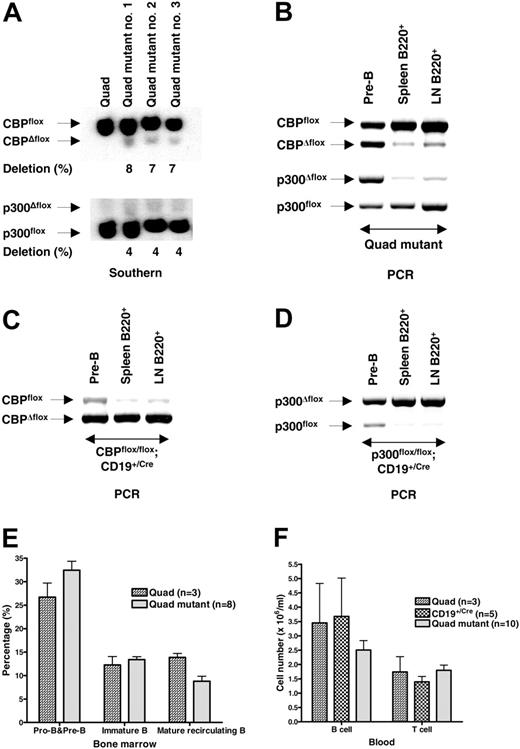

The combined dosage of CBP and p300 is critical for peripheral B cells

The ability of B cells to develop and survive with only CBP or p300 raised the possibility that cells lacking both coactivators could be generated. We tested this by creating CBPflox/flox;p300flox/flox; CD19+/Cre mice (“quad mutants”), which were compared with CBPflox/flox;p300flox/flox “quad” control mice. Quantitative Southern blot analysis of FACS-purified quad mutant splenic B cells detected only about 4% to 8% recombination of CBPflox and p300flox alleles, suggestive that cells lacking both CBP and p300 are selected against (Figure 5A). The low levels of Δflox alleles detected could be from B cells with incomplete recombination or perhaps viable double-null B cells. We next tested if quad mutant B cells were at a selective disadvantage by determining the frequency of gene deletion in purified pre-B cells from the bone marrow and B cells from the spleen and lymph nodes. Semiquantitative PCR analysis of DNA isolated from quad mutants showed a marked reduction in the percentage of recombined alleles in peripheral B cells when compared with pre-B cells (Figure 5B), the former of which was quantitatively similar (∼6% CBPΔflox) to the Southern blot result (Figure 5A). In contrast, CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre and p300flox/flox; CD19+/Cre B cells from the spleen and lymph node had a greater percentage of the recombined alleles compared with bone marrow pre-B cells (Figure 5C-D; PCR quantitation is fairly linear for CBPΔflox but tends to overestimate the relative abundance of the p300Δflox allele). These results strongly indicate that B cells require CBP or p300 in order to populate the periphery.

We unexpectedly observed marginal effects on B-cell development in the quad mutants as determined by flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells for B220 and IgM (Figure 5E) and B220 and CD43 (W.X., data not shown). The quad mutant looked similar to the CBP mutant in this respect. Quad mutant mice also had only an approximately 30% decrease in the number of B cells in the blood compared with controls (Figure 5F), indicating that there is compensation by homeostatic proliferation of peripheral B cells that did not recombine the conditional alleles. These results suggest 3 possibilities. First, loss of CBP and p300 does not strongly affect B-cell development but is highly detrimental to peripheral B cells. Second, loss of CBP and p300 is detrimental to B-cell progenitors, but cells having nonrecombined alleles can expand to fill the bone marrow niche. Third, quad mutant progenitors retain sufficient CBP and p300 protein to enable development because of insufficient protein turnover/dilution but die as CBP and p300 become limiting.

Loss of CBP or p300 attenuates BCR-inducible gene expression. Real-time RT-qPCR of RNA from FACS-purified splenic B cells of the indicated genotypes following 4 hours treatment with or without soluble anti-IgM. Test gene expression was normalized to signal derived from β-actin mRNA and then normalized to the lowest signal for each gene in a given experiment. Gene tested and the number of mice of each genotype are indicated (mean ± SEM).

Loss of CBP or p300 attenuates BCR-inducible gene expression. Real-time RT-qPCR of RNA from FACS-purified splenic B cells of the indicated genotypes following 4 hours treatment with or without soluble anti-IgM. Test gene expression was normalized to signal derived from β-actin mRNA and then normalized to the lowest signal for each gene in a given experiment. Gene tested and the number of mice of each genotype are indicated (mean ± SEM).

Loss of both CBP and p300 is highly detrimental for peripheral B cells. (A) Quantitative Southern blot of DNA of FACS-purified splenic B cells from control CBPflox/flox;p300flox/flox (Quad) and 3 different quadruple mutant CBPflox/flox;p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (Quad mutant) mice. Position of each allele and percent deletion are indicated. (B) Semiquantitative PCR of DNA isolated from quad mutant bone marrow pre-B cells (B220+ CD43–IgM– purified by FACS) and B cells (B220+ purified by FACS) from the spleen and lymph node (LN). Positions of PCR products representing each allele are indicated. PCR tends to overestimate the abundance of the p300Δ/flox allele. Semiquantitative PCR of DNA isolated from CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (C) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (D) B cells as in panel B. (E) Quantification of B-cell progenitors as determined by B220 and IgM flow cytometry (lymphocyte gate) of bone marrow derived from mice of the indicated genotypes. Number of mice is indicated (mean ± SEM). (F) The number of B and T cells per mL of peripheral blood from mice of the indicated genotypes. Number of mice is indicated (mean ± SEM).

Loss of both CBP and p300 is highly detrimental for peripheral B cells. (A) Quantitative Southern blot of DNA of FACS-purified splenic B cells from control CBPflox/flox;p300flox/flox (Quad) and 3 different quadruple mutant CBPflox/flox;p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (Quad mutant) mice. Position of each allele and percent deletion are indicated. (B) Semiquantitative PCR of DNA isolated from quad mutant bone marrow pre-B cells (B220+ CD43–IgM– purified by FACS) and B cells (B220+ purified by FACS) from the spleen and lymph node (LN). Positions of PCR products representing each allele are indicated. PCR tends to overestimate the abundance of the p300Δ/flox allele. Semiquantitative PCR of DNA isolated from CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre (C) and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre (D) B cells as in panel B. (E) Quantification of B-cell progenitors as determined by B220 and IgM flow cytometry (lymphocyte gate) of bone marrow derived from mice of the indicated genotypes. Number of mice is indicated (mean ± SEM). (F) The number of B and T cells per mL of peripheral blood from mice of the indicated genotypes. Number of mice is indicated (mean ± SEM).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that individually CBP and p300 are not highly essential for major aspects of B-cell development and function beyond the pro-B stage. This was unexpected, as the combined levels of CBP and p300 are generally presumed to be limiting; their described interactions with 36 different B-cell–critical transcriptional regulators support this view. CBP was moderately more important than p300 in peripheral B cells when it was lost after the pro-B stage. This may indicate that CBP protein is relatively more abundant compared with p300 in B cells or that it has unique B-cell–critical biochemical properties.

Although individual loss of CBP or p300 was fairly well tolerated, B cells lacking both coactivators were nonexistent or very rare in the periphery. This indicates that this small family of coactivators is indispensable and that other transcriptional cofactors like GCN5 and P/CAF that share functionalities with CBP and p300 (ie, protein acetyltransferase activity and a bromodomain for binding acetylated lysines) cannot supply completely redundant functions, at least in lymphocytes. CBP and p300 have a number of unique domains that function predominately to bind other proteins; our results suggest that there are no functional substitutes for all these domains outside the CBP/p300 family.

It is uncertain if loss of both CBP and p300 starting at the pro-B stage was detrimental to quad mutant B-cell development in bone marrow, although the effect on peripheral B cells was clear (Figure 5). CD19Cre-mediated recombination of both CBPflox and p300flox in quad mutant pre-B cells was considerably less than in cells deleting either floxed gene alone. This would suggest that progenitors lacking both CBP and p300 are selected against. The percentages, however, of pro-B, pre-B, and immature B cells were comparable between quad mutant and quad control mice, implying that cells lacking both CBP and p300 develop normally, although it is possible that cells retaining CBP and p300 protein expand to fill the niche. Comparison of the floxed gene recombination frequencies in pro-B, pre-B, and immature B cells in quad mutant mice would help resolve this question.

Cell survival in the bone marrow and periphery, or migration from bone marrow, may be aberrant in the quad mutants. We believe that survival is likely to be affected because the deletion frequency of both CBPflox and p300flox in quad mutant pre-B cells is less than if only one of the conditional alleles is present (ie, possible selection against double-null cells). There is also no obvious accumulation or blockage at any precursor stage in quad mutant bone marrow (Figure 5). The mechanism causing the loss of quad mutant B cells is unknown but may involve a deficit in BCR-responsive transcription (discussed in the following paragraph). In this regard, attenuated NF-κB–dependent transcription in quad mutant B cells may contribute to the phenotype; CD19Cre-mediated inactivation of the NF-κB regulators IKK2 and NEMO has little effect on B-cell development in the bone marrow but reduces mature B-cell numbers.54

Global gene expression was not greatly altered in resting CBP null B cells as measured by microarray, which is consistent with the modest B-cell phenotype. It is worth noting, however, that the effects of CBP and p300 loss on gene expression are underestimated because the frequency of deletion in bulk populations was always less than 100%. In contrast, the moderately reduced numbers of peripheral B cells in CBPflox/flox;CD19+/Cre, and to a lesser degree p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre, mice correlated with attenuated BCR-responsive gene expression. BCR signaling is essential for the maintenance of resting mature B cells,55 although the crucial downstream target genes are unclear. It is believed that NF-κB is one of the key transcription factors mediating BCR survival and proliferation signals, and we observed attenuated BCR-inducible expression in CBP and p300 null B cells of the NF-κB targets A1 and cyclin D2, which are thought to have roles in these processes. Expression measured by microarray of the NF-κB family member genes Nfkb1, Nfkb2, Rel, and Rela was not significantly different in CBP null B cells, although Relb was reduced approximately 1.7-fold (data not shown; Table 2).

TNF-α expression in response to BCR signaling was sensitive to the loss of CBP or p300, in general agreement with the findings by Falvo et al38 who used TCR-activated CBP+/– T cells. LPS-dependent TNF-α expression in macrophages that were deficient for CBP or p300 was not strongly affected, however, indicative that transcriptional regulators for this gene differ between cell lineages or signaling pathways.3

The mild B-cell phenotype seen in p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre mice was initially perplexing because we previously showed that p300KIX/KIX knock-in mutant mice have a marked deficiency in peripheral B cells.40 The p300KIX mutation abrogates the interaction of the p300 KIX domain with the principal activation domains of c-Myb and CREB. The disparity between the p300KIX/KIX and p300flox/flox;CD19+/Cre phenotypes could be explained if the p300 KIX domain is essential prior to, or during, the pro-B stage of development. Alternatively, there may be a delay in p300 protein and mRNA turnover following p300flox recombination, which initiates at the pro-B stage in mice with the CD19Cre allele. This would prevent a deficiency of p300 KIX domain function at the pro-B and possibly later stages. We addressed these 2 models by inactivation of p300flox in HSCs using p300flox/flox;Mx-Cre mice, which led to a substantial deficit in pro-B and pre-B progenitors, indicating that p300 has a crucial role in B lymphopoiesis prior to, or during, the pro-B stage. There is precedence for CBP/p300 interacting transcription factors being required very early in B-cell development but not at later stages. For example, the conventional knockout of PU.1 shows that it is essential for B cells but the conditional knockout reveals that it is not required beyond the pre-B-cell stage.56

It is somewhat counterintuitive that loss of both CBP and p300 did not lead to a significant decrease in peripheral B cells, even though loss of CBP alone causes a modest deficit. There are several possible explanations for this observation. First, B cells lacking CBP alone may function in a cell-nonautonomous manner to suppress homeostatic mechanisms; since B cells lacking both CBP and p300 are very rare or nonexistent outside of the bone marrow where B-cell development occurs, homeostatic compensation of peripheral B-cell numbers would function normally in CBPflox/flox; p300flox/flox; CD19Cre mice. Second, homeostatic “cell counting” mechanisms may respond more efficiently to a profound deficit in peripheral B cells (ie, the lack of double-null B cells) than if cells are modestly affected in the periphery as with CBPflox/flox; CD19Cre mice. Third, CBP null peripheral B cells themselves may be defective for homeostatic proliferation.

In summary, we have discovered that the 2 most heavily connected transcriptional coactivators known are individually only marginally limiting in peripheral B cells. Even though they do not appear to separately have very unique roles in mature B cells, CBP and p300 function to maintain B-cell homeostasis, and p300 is particularly important during very early B lymphopoiesis. The loss of both CBP and p300, however, shows that the CBP/p300 family is extremely important for B lymphocytes. Finally, the absence of a robust phenotype in singly homozygous null mice suggests that there is an unexpected degree of functional redundancy supplied by coactivators unrelated to CBP and p300. This may indicate that coactivator networks are decidedly more robust and interconnected than typically appreciated,2 although the identities of the CBP/p300-compensating factors are unknown.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 19, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3263.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 CA076385 (P.K.B.) and R01 HL073284 (D.W.), American Cancer Society grant RSG CCG-106204 (D.W.), Cancer Center (CORE) support grant P30 CA021765-28, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St Jude Children's Research Hospital.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

Thanks to M. Biesen, S. Lerach, M. Randall, and C. Barlow for excellent technical assistance; L. Kasper and D. Bedford for helpful comments on the manuscript; R. Cross, J. Gatewood, and J. Smith and the Mouse Immunophenotyping core; R. Ashmun and the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Shared Resource; and the Animal Resource Center at SJCRH. The Hartwell Center at SJCRH provided oligonucleotides and Affymetrix analyses.