A novel gene, CLL up-regulated gene 1 (CLLU1)—possibly implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)—has been identified, cloned, and characterized.

Numerous studies have searched for genes involved in the pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), with several aims. The first is to unravel the still elusive cell of origin of CLL. The second is to improve our limited knowledge of the genetic events that underlie the malignant transformation. The third is to track the natural history of the disease and define a biologically based prognostic approach to individual patients.1 In this context, the variable clinical course has been related to the presence or the absence of somatic hypermutations in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IgVH) of the B-cell antigen receptor (BCR).2,3 The fourth aim relates to the possibility that the microenvironment may influence the malignant cell's behavior.4 FIG1

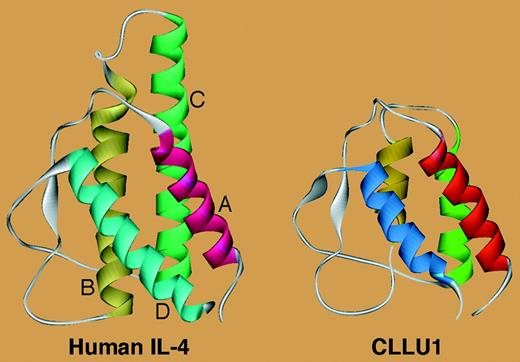

Similarity between the CLLU1-encoded protein and IL-4. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2904.

Similarity between the CLLU1-encoded protein and IL-4. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2904.

The study of Buhl and colleagues falls within this general scenario. Using the technique of differential display, which has the advantage of identifying not only known but also novel mRNAs, the authors have compared gene expression in CLL cells with and without IgVH mutations and have identified a gene—CLLU1—that encodes 6 mRNAs with no sequence homology to any known gene. Appreciable levels of CLLU1 were detectable by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) only in CLL cells and not in a large panel of normal tissue extracts, normal B-cell subsets, human leukemia cell lines, or a range of other blood malignancies including acute and chronic lymphoid tumors. CLLU1 was mapped to chromosome 12q22, in an area that does not include any known microRNA (miRNA). CLLU1 expression was nevertheless unrelated to trisomy 12 and also independent from large chromosomal rearrangements. CLL unmutated cases showed a strikingly higher level of CLLU1 expression (several hundred fold) compared with mutated ones, which in turn showed a median 5.7-fold up-regulation compared with normal B cells.

These findings raise a number of questions. It may be asked whether CLLU1 is an example of the long-sought CLL-specific gene, and whether it can become a therapeutic target. It is also conceivable that it can be used as a prognostic marker to easily discriminate mutated from unmutated cases. A further issue is whether CLLU1 expression reflects a hitherto unknown genetic aberration or whether it reveals a CLL-specific microenvironment stimulation that differs between mutated and unmutated cases. The answer to some of these questions likely lies in the definition of CLLU1 function. None of the detected transcripts can form the characteristic hairpin structure required for the generation of miRNAs. Of interest, 3D-structure modelling revealed that 2 of the 6 CLLU1 gene transcripts potentially encode a peptide that shows remarkable structural similarity to human IL-4 and appears to retain the capacity to interact with the IL-4 receptor (see figure). Considering that IL-4 may be involved in the microenvironment stimulation of CLL cells,4 the observation that the 2 CLL cell lines studied (MEC1 and MEC2)—although unmutated—express CLLU1 levels as low as fresh mutated samples may be a hint reflecting the importance of in vivo microenvironment stimulation in CLLU1 expression. ▪

Comment on Buhl et al, page 2904