Abstract

Most CD4+CD25hiFOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) from adult peripheral blood express high levels of CD45RO and CD95 and are prone to CD95L-mediated apoptosis in contrast to conventional T cells (Tconvs). However, a Treg subpopulation remained consistently apoptosis resistant. Gene microarray and 6-color flow cytometry analysis including FOXP3 revealed an increase in naive T-cell markers on the CD95L-resistant Tregs compared with most Tregs. In contrast to Tregs found in adult humans, most CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells found in cord blood are naive and exhibit low CD95 expression. Furthermore, most of these newborn Tregs are not sensitive toward CD95L similar to naive Tregs from adult individuals. After short stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), cord blood Tregs strongly up-regulated CD95 and were sensitized toward CD95L. This functional change was paralleled by a rapid up-regulation of memory T-cell markers on cord blood Tregs that are frequently found on adult memory Tregs. In summary, we show a clear functional difference between naive and memory Tregs that could result in different survival rates of those 2 cell populations in vivo. This new observation could be crucial for the planning of therapeutic application of Tregs.

Introduction

There is now clear evidence that CD4+ T cells contain a population of naturally immunosuppressive T cells characterized by constitutive expression of CD25, CTLA-4, and FOXP3.1 Because not all potentially autoreactive T cells are deleted in the thymus,2,3 peripheral control of T-cell responses by naturally occurring CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ immunoregulatory T cells (Tregs) is crucial to prevent autoimmunity.1 Depletion of Tregs contributes to the induction of severe autoimmune diseases in animal models, and several studies have reported a defect of Tregs in various human autoimmune diseases.1,4,5

Despite extensive research to unravel the immunosuppressive function of Treg, the exact molecular mechanism of immunosuppression is still elusive. Promising targets for pharmacologic mimicking of Tregs function remain undefined. Consequently, direct use of Tregs for therapy is currently under examination. Therapeutic expansion or depletion of Tregs with defined antigen specificity offers new treatment options for human diseases.6 Because accumulation of Tregs has been shown to be detrimental in cancer,7 new insights into mechanisms of Treg homeostastis are required.

To gain new insight into the modulation of Treg numbers as well as their antigen specificity, the development of natural Tregs during ontogeny and in the adult needs to be explored. The peripheral Treg compartment consists mainly of thymus-derived Tregs.1 However, under specific circumstances Tregs can also be generated out of conventional T cells (Tconvs) (eg, if the antigen is targeted to immature dendritic cells [DCs]).8-10 It has yet to be established how much “converted” Tregs contribute to the total number of Tregs in the periphery of adult mice and humans.

At a given time, the overall number of Tregs is defined by a balance of generation and demise of Tregs. At the end of an immune reaction, T cells are depleted by apoptosis. Activation-induced cell death (AICD) through CD95/CD95L has been described as such an apoptosis-inducing mechanism.11 While naive T cells are CD95– and resistant to apoptosis induction, activated T cells (CD45ROhi) up-regulate CD95 and become sensitive to apoptosis. Upon T-cell receptor (TCR) restimulation, activated effector T cells (Teffs) up-regulate CD95L and induce AICD through crosslinking of CD95 by CD95L. AICD eliminates Teffs after an immune response and contributes to T-cell homeostasis. We have previously shown that most Tregs constitutively express CD95 and can easily be killed via crosslinking of this death receptor by CD95L.12 Together with the fact that most Tregs express high levels of CD45RO, we hypothesized that most Tregs resemble memory/recently activated T cells rather than naive T cells. Only very recently has the presence of naive Tregs of CD4+CD25+CD45RAhi phenotype in addition to memory Tregs been appreciated in peripheral blood.13-15 However, because naive Tregs express less CD25 (CD25+) than memory Tregs (CD25hi) and because those studies did not include fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of FOXP3 expression, a clear separation between CD25+ Tregs and CD25+ Teffs was not possible. Therefore, analysis of CD4+CD25+CD45RAhi T cells might have included contaminating Teffs. Moreover, no functional differences between naive and memory Tregs were described; both cell types were reported to be immunosuppressive.14,15 In contrast, memory Tconvs are highly differentiated cells with distinct biologic properties from those of naive Tconvs. Analagously, naive and antigen-primed/memory Tregs should exhibit different functional features.

Here we analyzed CD95 expression levels and apoptosis sensitivity of Treg subpopulations. We showed that naive Tregs are resistant to CD95L-mediated apoptosis in contrast to memory Tregs. First, gene microarray analysis of CD95L-mediated apoptosis-resistant Tregs (rTregs) revealed a naive T-cell signature of rTregs. A 6-color FACS analysis was performed to detect FOXP3 and typical memory/naive T-cell markers on Tregs from adult peripheral blood. Naive Tregs constitute only 0.2% to 0.8% of total human CD4 cells, whereas in cord blood most Tregs belong to this naive apoptosis-resistant subpopulation. Short-term TCR stimulation in vitro converted these naive Tregs into CD95L-sensitive Tregs similar to adult memory (CD4+CD25hi) Tregs. In vivo, recognition of self antigens by Tregs might lead to the conversion of most Tregs into memory cells, and previous studies focused on CD25hi memory Tregs to avoid Teff contamination of the Treg pool. However, under pathogenic conditions like human autoimmunity we expect alterations of adult memory Treg frequencies (eg, due to enhanced CD95L-mediated apoptosis as reported for [CD4+CD25hi] Tregs derived from systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE] patients).16 In such situations, the analysis of the so far neglected naive Treg pool might be of great importance.

Materials and methods

Human samples

Peripheral blood was obtained from healthy adult donors. Cord blood samples were obtained from the placentas of healthy full-term newborns delivered at the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at the University of Heidelberg. All samples were obtained after informed consent and approval by the University of Heidelberg ethics committee according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Abs and reagents

The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against human CD4, CD45RO, CD45RA, and CD31 were obtained from BD Pharmingen (Heidelberg, Germany) and αCD25 Ab from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). CD95L was produced as a Leucin zipper-tagged ligand of CD95, which binds both murine and human CD95.17 The monoclonal αCD3 Ab (OKT3), αCD28 mAb, and the agonistic monoclonal αCD95 Ab (anti–Apo-1) were purified from hybridoma supernatants by protein A affinity purification as described.17 The monoclonal αFoxP3 mAb (clone PCH101) was obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA), annexin V Alexa Fluor 488 from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), and propidium iodide (PI) and protein A from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Lymphocyte separation

Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were purified from peripheral blood by Biocoll (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) gradient centrifugation followed by plastic adherence to deplete monocytes. Adult peripheral CD4+CD25+ cells were first enriched using magnetic-activated cell separation (MACS) beads (Miltenyi Biotec), and subsequently CD4+CD25high cells were sorted with a FACS-Diva cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). CD4+CD25hi Tregs cells contained only the 1% to 2% of human CD4 cells with the highest CD25 expression, as previously reported.18 Similarly, CD4+CD25+ or CD4+CD25+CD45ROlo/hi T cells were FACS sorted from cord blood–derived lymphocytes. FACS-sorted CD4+CD25– cells were used as Tconvs.

Dead cell removal

Dead cells were depleted using the MACS annexin V MicroBead kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Briefly, cells were incubated with annexin V microbeads and passed over a medium-size (MS) column to magnetically remove annexin V–positive cells. Purity of viable cells was determined by forward scatter/sideward scatter (FSC/SSC) analysis and propidium iodide staining.

Cell culture and cytotoxicity assays

Freshly isolated human T cells were cultured in IL-2 (100 IU) containing ex Vivo-15 medium (Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 1% glutamine (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). For apoptosis induction, T cells were stimulated with αCD95 Ab and 10 ng/mL protein A or different concentrations of CD95L (maximal 1:20 dilution) as previously described.12 Unstimulated cells were incubated with an isotype control Ab or CD95L-free control medium. To expand Tregs, cells were incubated with 0.1 μg/mL αCD3 Ab and 1 μg/mL αCD28 Ab in combination with irradiated JY feeder cells (kind gift from C. Falk, GSF-Institute for Molecular Biology, Munich, Germany) and 300 IU IL-2.12 Cell death was assessed by annexin V/propidium iodide costaining and forward to sideward scatter profiles. Specific cell death was calculated as described previously.12

Cell proliferation assay

When expanded Tregs were used, they were washed extensively to remove IL-2, but no further resting of Tregs occurred prior to cell proliferation assays. Tconvs (1 × 104) were incubated in 96-well plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) alone or in coculture with Tregs (1 × 104 Tregs) together with irradiated T-cell–depleted PBMCs (1 × 105) and were stimulated with soluble αCD3 mAb (0.2 μg/mL) and αCD28 mAb (0.005 μg/mL). Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and Tconvs were always derived from the same blood sample. After 4 days at 37°C in 5% CO2, 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) [3H]-thymidine per well was added for additional 16 hours, and proliferation was measured in counts per minute (cpm) with a scintillation counter. Inhibitiory capacity (percentage) of Tregs in coculture experiments was defined as (1 – 3[H]-thymidine uptake [cpm] of coculture of Tregs with Tconvs divided by cpm of Tconvs alone) × 100%. Triplicate wells were used in all suppression experiments.

FACS staining

FOXP3 staining was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. For 6-color FACS, cells were first stained with the surface mAb of interest followed by FOXP3 intracellular staining. FACS acquisition was performed immediately with a FACS Canto cytometer and analyzed with FACS-Diva software (BD Biosciences).

RNA preparation and quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the Absolutely RNA Microprep kit (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany), and cDNA was prepared using random oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen). The FOXP3 message was quantified by detection of incorporated SYBR Green using the ABI Prism 5700 sequence detector system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The relative expression level was determined by normalization to GAPDH, and results are presented as fold expresssion of Tconv mRNA levels. FOXP3 primer sequences were 5′-AGCTGGAGTTCCGCAAGAAAC (forward) and 5′-TGTTCGTCCATCCTCCTTTCC (reverse). GAPDH primer sequences were 5′-GCAAATTCCATGGCACCGT (forward) and 5′-TCGCCCCACTTGATTTTGG (reverse).

DNA microarray hybridization and analysis

Quality and integrity of 500 ng total RNA were controlled by running all samples on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). For RNA amplification, the first round was done according to Affymetrix without biotinylated nucleotides using the P1300 RiboMax Kit (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) for T7 amplification. For the second round of amplification, the precipitated and cleaned aRNA was converted to cDNA using random hexamers (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). Secondstrand synthesis and probe amplification was performed as in the first round, with 2 exceptions: There was an incubation with RNAse H before first-strand synthesis to digest the aRNA, and T7T23V oligo was used for initiation of the synthesis of the second strand. The concentration of biotin-labeled cRNA was determined by UV absorbance. In all cases,12.5 μg of each biotinylated cRNA preparation was fragmented and placed in a hybridization cocktail containing 4 biotinylated hybridization controls (BioB, BioC, BioD, and Cre) as recommended by the manufacturer. Samples were hybridized to an identical lot of Affymetrix HG-U133A 2.0 for 16 hours. After hybridization the GeneChips were washed, stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin (SA-PE), and read using an Affymetrix Gene-Chip fluidic station and scanner.

Microarray data analysis

Analysis of microarray data was performed using the Affymetrix GCOS 1.2 software. For global normalization, all array experiments were scaled to a target intensity of 150, otherwise using the default values of the GCOS 1.2 software. Filtering of the results was done as follows: Genes were considered as regulated when their fold change was greater than or equal to 1.2 or less than or equal to –1.2 and the statistical parameter for a significant change (change call) was not NC (no change). The entire Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAME)–compliant data set of the microarray experiments will be posted at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database.19

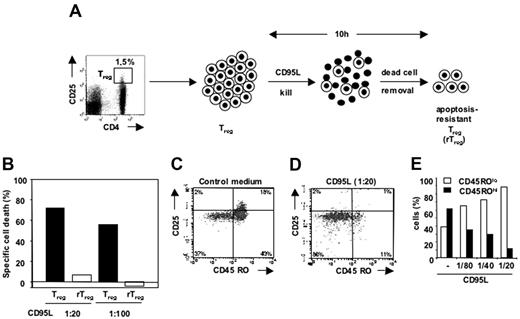

Resistance to CD95L-mediated apoptosis of a Treg subpopulation. (A) Isolation of apoptosis-resistant Tregs (rTregs). FACS-sorted Tregs were incubated with CD95L (1:20), and rTregs were recovered after removal of dead cells using annexin V microbeads as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) rTregs were incubated with different concentrations of CD95L, and specific cell death rates were compared with those of Tregs cultured in control medium. (C-D) FACS-sorted Tregs (CD4+CD25hi) were incubated alone (C) or with CD95L (1:20) (D), and the remaining cells were analyzed for the expression of CD25 and CD45RO. (E) The percentage of CD45ROlo and CD45ROhi subpopulations among the total surviving cell population was determined for various concentrations of CD95L.

Resistance to CD95L-mediated apoptosis of a Treg subpopulation. (A) Isolation of apoptosis-resistant Tregs (rTregs). FACS-sorted Tregs were incubated with CD95L (1:20), and rTregs were recovered after removal of dead cells using annexin V microbeads as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) rTregs were incubated with different concentrations of CD95L, and specific cell death rates were compared with those of Tregs cultured in control medium. (C-D) FACS-sorted Tregs (CD4+CD25hi) were incubated alone (C) or with CD95L (1:20) (D), and the remaining cells were analyzed for the expression of CD25 and CD45RO. (E) The percentage of CD45ROlo and CD45ROhi subpopulations among the total surviving cell population was determined for various concentrations of CD95L.

Results

CD4+CD25hi Tregs contain a subpopulation of CD95L-mediated cell death–resistant Tregs

We have previously shown that most CD4+CD25hi regulatory T cells (Tregs) are highly susceptible to CD95L-mediated cell death in contrast to conventional CD4+25lo T cells (Tconvs).12 Interestingly, a subpopulation of Tregs remained consistently apoptosis resistant to the treatment with CD95L. This apoptosis-resistant population (rTregs) represents a minor subpopulation (10% to 30%) within the sorted CD4+CD25hi Tregs.12 To further analyze this population, FACS-sorted CD4+CD25hi Tregs from multiple donors were pooled and incubated with CD95L. Dead Tregs were removed by annexin V microbeads, and the cell-death–resistant rTregs were recovered (Figure 1A). During a second challenge with CD95L (Figure 1B) or αCD95 mAb (data not shown) these rTregs remained apoptosis resistant, confirming that they display a stable phenotype. As a control, CD4+CD25hi Tregs were left without CD95L, incubated with annexin V microbeads, passed over MS columns, washed, and subsequently incubated with CD95L. As expected, specific cell death for these total CD4+CD25hi Tregs remained high (Figure 1B).

CD45ROlo Tregs are resistant to CD95L-mediated cell death

To further characterize rTregs, we pooled rTreg cDNA derived from FACS-sorted CD4+CD25hi Tregs of 8 healthy blood donors and performed gene chip microarray analysis. In this screen, we compared cDNA from rTregs with cDNA derived from all CD4+CD25hi Tregs. Interestingly, rTregs showed a significant decrease of mRNA expression of genes related to T-cell memory like CTLA-4, various HLA genes, and CD103, whereas mRNA for molecules expressed mainly on naive cells such as CCR7 or CD127 (IL7R) was more prevalent in rTregs than in total CD4+CD25hi Tregs (Tables S1-S2, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Tables link at the top of the online article). This finding suggested that rTregs are more naive in contrast to most Tregs found in the CD4+CD25hi T-cell population, which are known to exhibit an antigen-primed/memory-like phenotype. To test this hypothesis, we incubated FACS-sorted CD4+CD25hi Tregs with increasing concentrations of CD95L. The remaining viable rTregs were then analyzed by 4-color FACS for the expression of the typical memory marker CD45RO 20 (Figure 1C-E) and the naive marker CD31 21,22 (data not shown). In contrast to Tregs cultured in control medium (Figure 1C), rTregs surviving CD95L stimulation were mostly CD45ROlo (more than 85%) (Figure 1D). The number of CD45ROhi cells progressively declined with increasing concentrations of CD95L (Figure 1E). The naive cell marker CD31 increased correspondingly on rTregs (data not shown). We conclude that CD95L preferentially kills CD45ROhi Tregs cells, leaving behind rTregs with a naive phenotype and slightly lower CD25 expression levels. Furthermore, FACS analysis for intracellular FOXP3 expression demonstrated that all rTregs were FOXP3+, and the anergy and suppressive capacity of in vitro–expanded rTregs (data not shown) further supported their classification as Tregs.

Human adult CD4+CD25hiFOXP3+ Tregs consist of memory and naive Tregs

Consequently, human Tregs should comprise a heterogeneous population with memory and naive Tregs. To prove that naive CD4+CD25hi T cells are indeed Tregs, we performed FOXP3 FACS analysis in PBLs. In the absence of further highly specific Treg markers, FOXP3 is considered to be the most reliable marker to identify Tregs in human peripheral blood to date.23 Therefore, we established 6-color FACS analysis including mAbs against CD4, CD25, and FOXP3 for Treg detection together with mAbs against CD45RO and CD45RA to distinguish memory and naive Tregs. Naive Tregs were initially considered as CD4+FOXP3+CD45ROlo cells (R2 in Figure 2A, right panel), and memory Tregs were characterized as CD4+FOXP3+CD45ROhi cells (R3 in Figure 2A, right panel). Using multicolor analysis one can ascertain that memory Tregs (blue) are mainly CD25hi while naive Tregs (red) are mainly CD25int and overlap with CD25int Teffs. Accordingly, pure FACS-based isolation of Tregs is limited to the CD25hi memory Treg-enriched cell pool, because surface expression of CD25 is quite similar between naive Tregs and FOXP3– CD4+CD25+ Teffs (Figure 2B). Naive Tregs showed a higher expression of CD45RA than memory Tregs (Figure 2C). Analysis of the naive cell marker CD31 also showed increased expression (data not shown). Comparison of CD95L-resistant cells in Figure 1D with the CD45ROlo naive Tregs (red) from the 6-color staining (Figure 2B-C) revealed a similar phenotype, supporting that apoptosis-resistant Tregs represent naive Tregs in adult peripheral blood. Because sensitization toward CD95L-mediated cell death includes up-regulation of CD95, we compared CD95 expression of naive and memory Tregs by 6-color FACS for expression of CD4, CD25, FOXP3, CD45RO, CD45RA, and CD95 (Figure 2D). Indeed, naive CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROlo Tregs (red) expressed very low levels of CD95 in comparison with the highly CD95+ memory Tregs (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROhi, blue, Figure 2D). Collectively, we define naive Tregs as CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROloCD95lo T cells and memory Tregs as CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROhiCD95hi T cells. Furthermore, we conclude that rTregs represent naive Tregs in adult peripheral blood. The frequency of naive Tregs varied between 10% to 50% of total Tregs in adult peripheral blood and clearly declined with increasing age (Figure 2E).

Detection of memory and naive Tregs among human adult CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs. (A) Freshly isolated adult PBLs were stained directly with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4, CD25, CD45RO, and CD45RA followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) and were analyzed with a FACS Canto cytometer. After gating for CD4+ T cells (R1), CD45ROhiFOXP3+ T cells (R3, blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ T cells (R2, red) were defined. Identical populations (blue, red) are shown in panels B and C. (B) Multicolor analysis allocates CD45ROhiFOXP3+T cells (blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ T cells (red) within the CD4+CD25+ population. (C) CD45ROhiFOXP3+T cells (blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ T cells (red) were analyzed for expression of CD45RA and compared with Tconvs. (D) PBLs were stained with directly fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD95, CD4, CD25, CD45RO, and CD45RA followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) to determine expression of CD95 on CD45ROhiFOXP3+ (R3 as in panel B, blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ (R2 as in panel B, red) cells. The dashed line represents isotype control. (E) Note the significant inverse correlation between the percentage of naive Tregs (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROloCD95lo T cells) among total Tregs and age. Dots correspond to individual samples tested. The solid line shows linear regression.

Detection of memory and naive Tregs among human adult CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs. (A) Freshly isolated adult PBLs were stained directly with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4, CD25, CD45RO, and CD45RA followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) and were analyzed with a FACS Canto cytometer. After gating for CD4+ T cells (R1), CD45ROhiFOXP3+ T cells (R3, blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ T cells (R2, red) were defined. Identical populations (blue, red) are shown in panels B and C. (B) Multicolor analysis allocates CD45ROhiFOXP3+T cells (blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ T cells (red) within the CD4+CD25+ population. (C) CD45ROhiFOXP3+T cells (blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ T cells (red) were analyzed for expression of CD45RA and compared with Tconvs. (D) PBLs were stained with directly fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD95, CD4, CD25, CD45RO, and CD45RA followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) to determine expression of CD95 on CD45ROhiFOXP3+ (R3 as in panel B, blue) as well as CD45ROloFOXP3+ (R2 as in panel B, red) cells. The dashed line represents isotype control. (E) Note the significant inverse correlation between the percentage of naive Tregs (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROloCD95lo T cells) among total Tregs and age. Dots correspond to individual samples tested. The solid line shows linear regression.

Cord blood CD4+CD25+ T cells are FOXP3+ and express low levels of CD95

Whereas the frequency of CD45ROlo Tregs in adult peripheral blood is rather low, newborns should exhibit high numbers of naive Tregs. Therefore, we extended our functional analysis on cord-blood–derived Tregs. Nearly all CD4+CD25+ human cord blood T cells expressed FOXP3 as determined by FACS analysis (Figure 3A) and quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (data not shown). The percentage of FOXP3+ T cells within the CD4+ compartment was only slightly higher in cord blood (5.9% ± 3.1%, n = 6) than in adult peripheral blood (4.8% ± 1.7%, n = 6). Tregs were sorted from adult and cord blood according to CD25 expression as depicted in Figure 3B and showed significant suppressive capacity in vitro (Figure 3C). Thus, all CD4+CD25+ T cells in human cord blood constituted CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs similar to murine Tregs. In contrast, few CD4+CD25+ T cells in adult peripheral blood contained CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs (Figure 3A). Further, FACS analysis revealed that most cord blood Tregs showed low expression of CD45RO (Figure 4B) but high expression of CD45RA and CD31 (data not shown), confirming their naive status. Interestingly, most cord blood Tregs showed a low expression of CD95 (Figure 3D) similar to adult naive Tregs. High expression of CD95 was limited to the minor subpopulation of CD45ROhi Tregs in cord blood (Figure 4B, arrow). To summarize, both naive Tregs from cord blood as well as naive Tregs from adult peripheral blood show a lower expression of CD95 than memory Tregs. In addition, both exhibit a similar level of CD25 expression (compare Figures 2B and 3A), further indicating that cord blood Tregs and adult naive Tregs represent a similar cell population.

Expression of FOXP3 and CD95 on T cells derived from cord blood. (A) Freshly isolated adult PBLs as well as cord blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4 and CD25 followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) and were analyzed with a FACS Canto cytometer. Cells were gated on viable CD4+ T cells. (B) Adult CD4+CD25hi, cord blood CD4+CD25+ T cells, and their respective Tconv counterparts were FACS sorted using the indicated gates, and (C) inhibitory capacities of FACS-sorted Tregs were analyzed by proliferation assays. For this purpose, Tconvs were FACS sorted from a third-party adult donor and incubated with cord blood Tregs or adult Tregs as described in “Materials and methods.” (D) Freshly isolated adult PBLs as well as cord blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4, CD25, and CD95 followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) and were analyzed on a FACS Canto cytometer. Histogram overlays indicate expression of CD95 on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells from cord blood versus adult blood. The isotype control for CD95 is shown for cord blood and was similar to isotype staining of adult PBLs. (E) Cord blood lymphocytes were stained as in panel D plus anti-CD45RO mAb. Histogram overlays indicate the expression of CD95 on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells as well as on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROhi T cells. Isotype control for CD95 staining is shown.

Expression of FOXP3 and CD95 on T cells derived from cord blood. (A) Freshly isolated adult PBLs as well as cord blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4 and CD25 followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) and were analyzed with a FACS Canto cytometer. Cells were gated on viable CD4+ T cells. (B) Adult CD4+CD25hi, cord blood CD4+CD25+ T cells, and their respective Tconv counterparts were FACS sorted using the indicated gates, and (C) inhibitory capacities of FACS-sorted Tregs were analyzed by proliferation assays. For this purpose, Tconvs were FACS sorted from a third-party adult donor and incubated with cord blood Tregs or adult Tregs as described in “Materials and methods.” (D) Freshly isolated adult PBLs as well as cord blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4, CD25, and CD95 followed by intracellular staining with anti-FOXP3 mAb (clone PCH101) and were analyzed on a FACS Canto cytometer. Histogram overlays indicate expression of CD95 on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells from cord blood versus adult blood. The isotype control for CD95 is shown for cord blood and was similar to isotype staining of adult PBLs. (E) Cord blood lymphocytes were stained as in panel D plus anti-CD45RO mAb. Histogram overlays indicate the expression of CD95 on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells as well as on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45ROhi T cells. Isotype control for CD95 staining is shown.

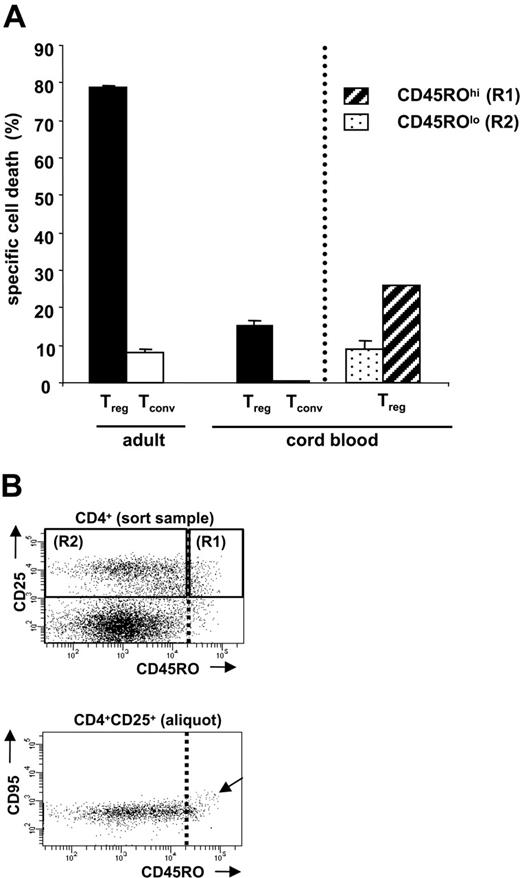

Freshly isolated cord blood Tregs are resistant to CD95L-mediated apoptosis

Next we tested whether cord-blood–derived Tregs were resistant to CD95L-mediated apoptosis similar to adult naive Tregs. In contrast to freshly isolated adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs, cord blood Tregs were nearly resistant toward CD95L-mediated cell death (Figure 4A). This correlates with the CD95hi phenotype of memory Tregs in the adult CD4+CD25hi Treg fraction (Figure 2D) and the rather low presence of such memory Tregs among freshly isolated cord blood Tregs (Figure 4B, arrow). Interestingly, the few CD45ROhi Tregs present in cord blood showed not only increased CD95 expression but also slightly enhanced sensitivity to CD95L-mediated apoptosis (Figure 4A, right).

TCR-stimulated cord blood Tregs are sensitive to CD95L-mediated apoptosis and acquire a memory phenotype similar to adult Tregs

During an immune response, naive Tconvs are stimulated via their TCR. They clonally expand and differentiate into Teffs. One hallmark of peripheral T-cell depletion is that Teffs up-regulate CD95 and become sensitive to CD95L-mediated cell death to allow depletion of the expanded T-cell pool by CD95L.11 We have shown that TCR stimulation of Tconvs from adult peripheral blood with anti-CD3 mAb and IL-2 can be used to mimic this critical process in vitro.11 Accordingly, we questioned whether naive Tregs could also up-regulate CD95 and be sensitized to CD95L-mediated apoptosis in response to TCR stimulation.

Resistance of cord blood Tregs toward CD95L-mediated cell death. (A) FACS-sorted adult Tregs (CD4+CD25hi), cord blood Tregs (CD4+CD25+), and their respective Tconvs were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours, and specific cell death rates were determined by FACS analysis as described previously.12 Similarly, CD4+CD25+CD45ROlo T cells (R2) as well as CD4+CD25+CD45ROhi T cells (R1) were FACS sorted as shown in panel B, and all cells were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Enrichment of naive or memory cord blood Tregs by FACS sorting. Cord blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4, CD25 and CD45RO. Previous to FACS sorting, one aliquot from the sort sample was additionally stained with anti-CD95 mAb to detect CD4+CD25+CD95hi T cells. Because CD4+CD25+CD95hi T cells cosegregate with CD45ROhi T cells (arrow), the sorting gate was set on CD45ROhi cells to separate CD4+CD25+CD45ROhi CD95hi memory T cells in R1 from the naive cord blood Tregs in R2. See the penultimate paragraph of “Results” for further explanation. One representative experiment of at least 3 independent experiments is shown.

Resistance of cord blood Tregs toward CD95L-mediated cell death. (A) FACS-sorted adult Tregs (CD4+CD25hi), cord blood Tregs (CD4+CD25+), and their respective Tconvs were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours, and specific cell death rates were determined by FACS analysis as described previously.12 Similarly, CD4+CD25+CD45ROlo T cells (R2) as well as CD4+CD25+CD45ROhi T cells (R1) were FACS sorted as shown in panel B, and all cells were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Enrichment of naive or memory cord blood Tregs by FACS sorting. Cord blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD4, CD25 and CD45RO. Previous to FACS sorting, one aliquot from the sort sample was additionally stained with anti-CD95 mAb to detect CD4+CD25+CD95hi T cells. Because CD4+CD25+CD95hi T cells cosegregate with CD45ROhi T cells (arrow), the sorting gate was set on CD45ROhi cells to separate CD4+CD25+CD45ROhi CD95hi memory T cells in R1 from the naive cord blood Tregs in R2. See the penultimate paragraph of “Results” for further explanation. One representative experiment of at least 3 independent experiments is shown.

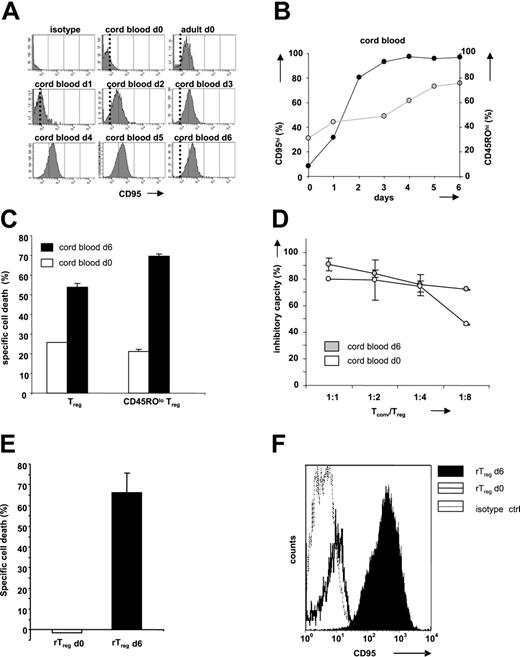

For this purpose, we stimulated freshly isolated cord blood Tregs with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs and IL-2 and analyzed their phenotypes at various time points (Figure 5). Soon after TCR stimulation, CD95 was up-regulated on cord blood Tregs and reached a CD95 expression plateau after 3 to 4 days (Figure 5A-B). This was notable because adult human T cells take 5 to 6 days to reach a plateau of CD95 expression (data not shown). However, murine T cells were also sensitized toward CD95L faster than adult T cells after TCR stimulation,24 which suggests that naive human cord blood T cells share similarities with murine T cells. Simultaneous FACS analysis of memory cell markers during the in vitro stimulation of cord blood Tregs revealed that CD45RO increased more gradually than CD95 (Figure 5B) and that CD45RA and CD31 were gradually lost until day 6 (data not shown). Thus, this in vitro–induced phenotype of cord blood Tregs (CD95hiCD45ROhiCD45RAlo) was identical with the phenotype of most adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs in vivo (Figure 2).

Most importantly, prestimulated cord blood Tregs were sensitive to CD95L treatment in contrast to freshly isolated cord blood Tregs (Figure 5C). To rule out outgrowth of a few preexisting cord blood CD45ROhiCD95hi Tregs, we aimed to exclude CD45ROhiCD95hi Tregs by FACS sorting. However, FACS sorting with anti-CD95 mAb could induce isolation-based apoptosis. Therefore, we defined an expression level of CD45RO that allowed separation of CD95hi from CD95lo cells without costaining for CD95 (dotted line in Figure 4B). This was performed using an aliquot of the FACS-sorting cells stained for CD45RO and CD95. After defining the CD45RO “cutoff,” the sorting cells were separated into CD45ROhi (correspondingly CD95hi) cells (Figure 4B, R1) and CD45ROlo (correspondingly CD95lo) cells (Figure 4B, R2). When we stimulated the CD45ROloCD95lo cord blood Tregs for 6 days, they still up-regulated CD95 and became sensitive toward CD95L-mediated apoptosis (Figure 5C). Therefore, outgrowth of CD45ROhiCD95hi Tregs could be ruled out.

Sensitization of cord blood Tregs toward CD95L-mediated cell death in response to TCR stimulation. FACS-sorted cord blood Tregs (CD4+CD25+) and adult Tregs (CD4+CD25hi) were incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs and IL-2 as described in “Materials and methods.” CD95 expression (A-B, •) and CD45RO expression (B, ○) were determined at the time points indicated. (C) Six days after TCR stimulation, cord blood Tregs were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours, and specific cell death rate was determined and compared with the specific cell death rate of freshly isolated cord blood Tregs. Likewise, freshly isolated FACS-sorted CD45ROlo cord blood Tregs without CD95hi memory Tregs (Figure 3B) were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours. (D) Proliferation assays were used to measure the inhibitory capacities of freshly isolated cord blood Tregs or 6-day activated Tregs (anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs plus IL-2). For this test, Tconvs were FACS sorted from an adult donor and incubated with cord blood Tregs as described in “Materials and methods.” (E-F) Apoptosis-resistant Tregs were incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs plus IL-2 as described in “Materials and methods.” After 6 days, CD95 sensitivity toward CD95-mediated apoptosis (E) and expression of CD95 (F) were determined. One representative experiment of at least 3 independent experiments is shown. Error bars represent SEM.

Sensitization of cord blood Tregs toward CD95L-mediated cell death in response to TCR stimulation. FACS-sorted cord blood Tregs (CD4+CD25+) and adult Tregs (CD4+CD25hi) were incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs and IL-2 as described in “Materials and methods.” CD95 expression (A-B, •) and CD45RO expression (B, ○) were determined at the time points indicated. (C) Six days after TCR stimulation, cord blood Tregs were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours, and specific cell death rate was determined and compared with the specific cell death rate of freshly isolated cord blood Tregs. Likewise, freshly isolated FACS-sorted CD45ROlo cord blood Tregs without CD95hi memory Tregs (Figure 3B) were incubated with CD95L (1:20) for 10 hours. (D) Proliferation assays were used to measure the inhibitory capacities of freshly isolated cord blood Tregs or 6-day activated Tregs (anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs plus IL-2). For this test, Tconvs were FACS sorted from an adult donor and incubated with cord blood Tregs as described in “Materials and methods.” (E-F) Apoptosis-resistant Tregs were incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs plus IL-2 as described in “Materials and methods.” After 6 days, CD95 sensitivity toward CD95-mediated apoptosis (E) and expression of CD95 (F) were determined. One representative experiment of at least 3 independent experiments is shown. Error bars represent SEM.

Likewise, isolated rTregs from adult blood up-regulated CD95 in response to TCR stimulation (anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs plus IL-2) and became sensitive to CD95L-mediated cell death (Figure 5E-F). Finally, freshly isolated adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs, naive cord blood Tregs, and prestimulated cord blood Tregs showed similar immunosuppressive capacity in vitro (Figures 3C and 5D). In contrast, up-regulation of CD95 and sensitization toward CD95L-mediated cell death clearly distinguished memory Tregs from naive Tregs on a functional basis.

Discussion

In our efforts to characterize CD95L apoptosis-resistant Tregs (rTregs) within the population of adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs, we found an increased expression of molecules defining naive T cells and a decreased expression of memory cell–associated molecules by microarray analysis. Further FACS analysis confirmed this finding and revealed that naive Tregs from adult and cord blood express low levels of CD95 and are resistant to CD95L-mediated cell death. This is in contrast to in vitro–prestimulated naive Tregs or in vivo–activated CD4+CD25hiCD45ROhi Tregs, which express high levels of CD95 and are highly sensitive to death receptor ligation. The number of Tregs in the organism is tightly regulated, and we propose that elimination of Tregs after an immune response contributes to the low frequency of Tregs in the adult CD4+ fraction.

CD95L-mediated apoptosis of T cells has mainly been studied in naive Tconvs that were activated in vitro. Analysis of apoptosis sensitivity of in vivo–primed/memory Teffs has been hampered by their low frequencies in the healthy human individual. By contrast, continuous in vivo stimulation of naive Tregs with self antigens seems to keep the proportion of CD95hi Tregs relatively high. In fact, incubation of naive Tregs with autologous APCs and IL-2 has been shown to stimulate naive Tregs in contrast to unreactive naive Tconvs,14 and Romagnoli and coworkers have shown a high degree of self-reactivity within the Treg population.25 Thus, a constant activation of Tregs in vivo could conceivably lead to a very high proportion of memory Tregs in adults. This high frequency of memory Tregs allowed us to demonstrate the high apoptosis sensitivity toward CD95L of these antigen-experienced Tregs with a memory-like phenotype directly ex vivo.

Whereas naive cord blood Tregs are CD95lo similar to naive Tconvs, TCR stimulation in vitro revealed a rapid up-regulation of CD95. Simultaneously, CD45RO was up-regulated, whereas expression of the naive marker molecule CD31 declined in slower kinetics (data not shown). Six days after TCR stimulation in vitro, most cord-blood–derived naive Tregs had acquired the phenotype (CD95hiCD45ROhiCD45RAlo) known from adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue in vivo.15 In summary, naive Tregs show the same phenotype in cord blood and adult peripheral blood but are much more frequent in cord blood. By contrast, memory Tregs predominate in adult peripheral blood and are rare in cord blood. However, short-time TCR stimulation in vitro transformed cord-blood–derived naive Tregs into Tregs of a memory-like phenotype presented by most adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs.

This in vitro induction of memory Tregs might mimic the interaction of naive Tregs with self antigens in vivo, which generates a pool of self-antigen–primed/memory-like Tregs very early in fetal ontogeny. Tregs can be detected as early as 14 weeks of human gestation in the periphery,26 and Tregs in fetal lymph nodes (less than 17 weeks old) already show a higher expression of CD95 and CD45RO in comparison with Tconvs.27 Because the healthy fetus is usually not challenged with foreign antigens, activation of Tregs might reflect the early interaction of Tregs with self antigens in the pathogen-free organism. Interestingly, Tregs in the fetal and adult thymus express lower levels of CD25 and are of naive phenotype, while Tregs in the fetal/adult lymphoid organs as well as in the adult peripheral blood express higher levels of CD25 (CD25hi) and are of memory phenotype (eg, CD95hi, CD45RO).15,27 Thus, after their emigration from the thymus, Tregs recognize self antigen in the periphery and convert to memory Tregs. During adult life ongoing self-antigen–specific activation of naive Tregs might trigger the immunosuppressive function of Tregs and thereby continuously supply the pool of memory CD4+CD25hi Tregs. Up-regulation of CD95 and high sensitivity toward CD95L-mediated cell death would then allow for constant elimination of antigen-experienced Tregs. Both the high turnover of mouse self-specific Tregs28-30 and the larger proportion of activated Tregs than Tconvs in the human periphery26 strongly support this model.

Previously, only CD4+CD25hi T cells have been accepted to represent human Tregs, and many studies have focused on this population because pure isolation of FOXP+ Tregs is limited to this population in humans. With the availability of specific FOXP3 mAbs for flow cytometry, we now detected naive Tregs with lower CD25 expression in adult peripheral blood. This confirmed recent reports that suggested the presence of naive Tregs within the CD4+CD25+CD45RAhi T-cell population of adult peripheral blood.14,15 However, our multicolor FOXP3-FACS analysis also revealed that CD4+CD25+CD45RAhi T cells consist of both FOXP3+ and FOXP3– T cells (data not shown). Therefore, FACS sorting for CD4+CD25+CD45RAhi T cells from adult peripheral blood yields a significant contamination with FOXP3– Tconvs. In fact, these contaminating Tconvs might contribute to the reported relatively high proliferative potential of adult naive Tregs in contrast to the profound anergy of CD4+CD25hi Tregs.14

It has long been appreciated that cord blood contains a distinct population of CD25+CD45RAhi Tregs with suppressive function. Although PCR analysis of these CD25+CD45RAhi cells has revealed FOXP3 expression,31-33 it remained unclear whether all cord blood CD25+ cells express FOXP3 and are Tregs. Our flow cytometric analysis clearly established that essentially all cord blood CD25+ cells coexpress FOXP3. Thus, FOXP3+ cells can easily be isolated from cord blood on the basis of their CD25 expression. Cord-blood–derived Tregs are immunosuppressive and show proliferative anergy like adult CD4+CD25hi Tregs.15,31,33,34 Most importantly, expression of FOXP3 seems to be more specific for naive Tregs than for recently activated Tregs. Activation-induced up-regulation of FOXP3 mRNA has been reported for in vitro–stimulated Teffs and triggered a controversial discussion on FOXP3 specificity for human Tregs.35-38 Interestingly, we also observe a slightly higher FOXP3 expression in memory Tregs than in naive Tregs, which might reflect the recent activation of memory Tregs by self antigen in vivo. However, naive FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells should unequivocally represent natural Tregs because Teffs with activation-induced FOXP3 expression (eg, peripherally generated Tregs) donot exhibit a naive phenotype. Furthermore, strict gating for CD4+CD25hi T cells had led to false low Treg numbers (1% to 2%) in human adult peripheral blood in many previous studies. With the detection of naive Tregs, total Tregs frequencies in mice (5% to 10%) and humans (3% to 7%) are actually comparable.

Modulation of the naive Treg pool could be an interesting target for therapeutic intervention. Sereti et al recently showed reconstitution of CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells in lymphopenic HIV patients after retroviral treatment. In response to IL-2 treatment, CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells rapidly expanded.39 Similarly, CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells have been reported to expand during rheumatoid arthritis.40 Although CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells expressed high amounts of FOXP3, Sereti and coworkers considered these cells to be different from Tregs because they were CD45ROlo, CD25int, and also weak suppressors unlike CD4+CD25hi Tregs. Moreover, CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells were reported to be CD95lo and resistant to CD95L-mediated apoptosis.39 Because these properties are all features of naive Tregs, we consider it highly likely that the reported CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells in treated HIV patients predominantly contained naive Tregs. Because FOXP3 was not analyzed at a single-cell level by flow cytometry, contamination of naive Treg cells with Tconvs within the analyzed CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T cells could not be detected. Such a contamination with Tconvs could explain the low IL-2 production and weak suppressive capacity of the CD4+CD25+CD45RO– T-cell population derived from HIV patients that was observed.

Altogether, several lines of evidence support the existence of naive FOXP3+ Tregs (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD95loCD45ROloCD45RAhi) and warrant thorough investigation of these cells in human disease. Naive and memory Treg frequencies should be considered as a result of different regulating mechanisms including generation, elimination, and transformation of naive Tregs into memory Tregs. It is important to delineate the predominating processes for Treg homeostasis in detail to allow a rational translation into human pathogenesis. This report provides a functional assay for the distinction between naive and antigen-primed Tregs, because resistance toward CD95L-mediated apoptosis clearly separates naive Tregs from their in vivo–preactivated CD4+CD25hi Tregs counterparts. Pathogenetically this difference might be relevant, because Miyara et al recently showed that reduced Treg frequencies in active SLE resulted from enhanced CD95-mediated cell death of SLE-derived CD4+CD25hi Tregs.16 However, only CD25hi Tregs, which are mainly composed of memory Tregs, were studied. Therefore, it remains possible that naive Treg numbers are increased in SLE to compensate for a relative loss of memory-like CD4+CD25hi T cells in SLE. As for other diseases with altered frequencies of CD4+CD25hi Tregs, an analysis of naive Tregs should accompany that of the quantity and function of Tregs. Altered distribution of both cell types within the Treg population might reflect not only age dependency but also fluctuating disease activity. Careful reanalysis of the previously neglected naive Tregs pool might help to optimize novel therapies based on the expansion of naive and apoptosis-resistant Tregs.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 25, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005660.

Supported by grants from the Gemeinnützige Hertie Stiftung (1.319.110/01/11 and 1.01.1/04/003), Landesstiftung Baden-Württenberg (P-65-AL/13) to N.O., and Young Investigator Award of the University of Heidelberg to B.F.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

B.F. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; N.O. performed research and analyzed data; E.P. contributed clinical samples and analyzed data; R.G. performed microarray analysis; J.B. contributed expertise in microarray analysis; J.P. contributed clinical samples; P.K. analyzed data and assisted in writing the paper; O.L. contributed clinical samples and assisted in writing the paper; and E.S.-P. designed research and wrote the paper.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

G. Faehnderich, C. Schneider, Dr A. Steinborn, and Prof Dr C. Sohn are gratefully acknowledged for making cord blood samples available to us. We thank K. Hexel and M. Scheuermann for FACS sorting and Dr A. Kuhn for assistance with recruitment of adult blood donors; T. Toepfer for excellent assistance in gene chip analysis; Dr R. Arnold, Dr K. Gülow, Dr M. Li-Weber, and S. Foehr for critical reading of the manuscript; and Prof Dr B. Arnold, Prof B. Wildemann, and Dr J. Haas for helpful discussion.