Abstract

Nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK) is a chimeric protein expressed in a subset of cases of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) for which constitutive expression represents a key oncogenic event. The ALK signaling pathway is complex and probably involves functional redundancy between various signaling substrates of ALK. Despite numerous studies on signaling mediators, the molecular mechanisms contributing to the distinct oncogenic features of NPM-ALK remain incompletely understood. The search for additional interacting partners of NPM-ALK led to the discovery of AUF1/hnRNPD, a protein implicated in AU-rich element (ARE)-directed mRNA decay. AUF1 was immunoprecipitated with ALK both in ALCL-derived cells and in NIH3T3 cells stably expressing NPM-ALK or other X-ALK fusion proteins. AUF1 and NPM-ALK were found concentrated in the same cytoplasmic foci, whose formation required NPM-ALK tyrosine kinase activity. AUF1 was phosphorylated by ALK in vitro and was hyperphosphorylated in NPM-ALK-expressing cells. Its hyperphosphorylation was correlated with increased stability of several AUF1 target mRNAs encoding key regulators of cell proliferation and with increased cell survival after transcriptional arrest. Thus, AUF1 could function in a novel pathway mediating the oncogenic effects of NPM-ALK. Our data establish an important link between oncogenic kinases and mRNA turnover, which could constitute a critical aspect of tumorigenesis.

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a T/null-cell neoplasm characterized by the expression of a hybrid protein comprising an N-terminal partner protein fused to the cytoplasmic portion of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase. The full-length ALK protein belongs to the family of receptor tyrosine kinases and is highly conserved across species.1 In approximately 80% of ALK-positive lymphomas, the hybrid kinase is the NPM-ALK fusion protein that is encoded by the nucleophosmin (NPM)-ALK fusion gene resulting from the (2;5)(p23;q35) chromosomal translocation.2-4 Other translocations have been described involving the ALK gene and other partners, including TFG,5 CLTC,6 ATIC, 6,7 and TPM3.8 In NPM-ALK, as well as in variant fusion proteins, the N-terminal partner protein is widely expressed in normal cells due to ubiquitous transcription of the corresponding promoter. Thus, cells that do not normally express the full-length ALK receptor because of its restricted tissue distribution4,9 display, if they contain an X-ALK translocation, anomalous transcription of the ALK chimeric mRNA and aberrant expression of the encoded fusion protein. In addition, the N-terminal partner protein (NPM or other variants) contains an oligomerization motif that enables the fusion protein to form homodimers as well as heterodimers with the full-length partner (Bischof et al10 and review in Pulford et al1 ). Oligomerization of the fusion protein results in the constitutive activation of the ALK tyrosine kinase catalytic domain contained in its carboxy-terminal part. This, in turn, leads to abnormal activation of multiple downstream signaling cascades that are responsible for the neoplastic transformation of cells, involving, among others, phospholipase C-gamma (PLCγ),11 phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K),12 STAT-3,13,14 and STAT-5,15 as well as Src kinases.16

Several model systems have been established to study the oncogenic mechanisms used by ALK fusion proteins, including transgenic mice, which develop lymphoma when NPM-ALK expression is directed to lymphocytes,17,18 and cultured cells which acquire transformed properties when they express ALK fusion protein11,19 (for a review, see Pulford et al1 ). A recent analysis of NPM-ALK-associated proteins in the t(2;5)-positive line Karpas 299 led to the identification of a number of proteins and highlighted the complexity of the molecular mechanisms underlying NPM-ALK oncogenicity.20

In this study, we characterized AUF1/hnRNPD as a new partner of NPM-ALK. AUF1 belongs to the family of AU-binding proteins (AU-BPs) that regulate the cellular half-lives of many mRNAs by directly interacting with an AU-rich element (ARE) located in their 3′ untranslated region.21-23 Although AREs are found in mRNAs coding for a wide range of proteins,24 many ARE-containing mRNAs are transcribed from early response genes (ERGs) encoding proto-oncogene products (such as c-Myc), cytokines, cyclins (such as cyclins D1, A2, and B1) and growth factors involved in the control of cell growth and proliferation. Here, we demonstrate that AUF1 is associated with NPM-ALK in human t(2;5)-positive ALCL lines and in murine NPM-ALK- or X-ALK-transformed NIH3T3 cells. Both proteins are found concentrated in cytoplasmic granules. ALK can phosphorylate AUF1 in vitro and AUF1 is found in a hyperphosphorylated state in NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells. The stability of several ARE-containing mRNAs known to be AUF1 targets is increased in NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells compared with controls and contributes to the enhanced cell survival observed after transcriptional arrest. Altering mRNA stability via hyperphosphorylation of AUF1 could represent an important aspect of NPM-ALK tumorigenicity.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, transfection, and immunocytochemistry

SU-DHL1 (a gift from M. Cleary, Stanford University, CA), Karpas 299,25 COST, and FEPD cells were grown in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Invitrogen, St Quentin en Yvelines, France). X-ALK stably transfected NIH3T3 cells are described in Armstrong et al.19 For actinomycin D pulse-chase experiments, 2 μg actinomycin D (Sigma, St Quentin Yvelines, France) was added per milliliter of cell-culture medium and RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen).

For immunofluorescence (IF) analysis, NIH3T3 cells were seeded on cover glasses (104 cells/mL), cultured overnight, fixed, permeabilized, and stained as described.26,27 The antibodies used were rabbit anti-AUF1 (dilution: 1/200); monoclonal anti-ALK128 (dilution: 1/10); rabbit anti-hDcp1a (dilution: 1/200) (generous gift of B. Séraphin, Centre de Génétique Moléculaire, Gif/Yvette, France), monoclonal anti-HuR (dilution: 0.5 μg/mL, 19F12; Clonegene, Hartford, CT). The secondary antibodies were goat antirabbit antibody (TRITC; Jackson Immunoresearch, Gagny, France) and goat antimouse (Alexa 488; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, St Quentin en Yvelines, France). Slides were mounted in Mowiol (Calbiochem, Strasbourg, France) and analyzed with a Leica SP2 confocal microscope (Leica, Rueil Malmaison, France) equipped with helium-neon lasers and appropriate filter combinations. Images in Figure 4 were visualized and acquired using a Leica TCS-SP2 microscope equipped with a 63×/1.32 numeric aperture (NA) objective with a zoom of 2× (for NIH3T3 cells) or 4× (for SU-DHL1, Karpas, and COST cells). Images were processed using Leica confocal software and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). ALCL-derived cells were pelleted, fixed, permeabilized, and stained as described for NIH3T3 cells. Images in Figure 6A were visualized and acquired using a Leitz fluorescence microscope (Le Pecq, France) equipped with a 25×/0.5 NA objective and a Nikon DXm1200 digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were processed using Nikon ACT-1 software and Adobe Photoshop.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

For 1D gel analysis, total protein extracts were prepared from NIH3T3 or ALCL cell lines as previously described;16 nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-ECL; Amersham, Orsay, France) were probed with anti-AUF1 (monoclonal 5B9, generous gift from G. Dreyfuss [Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia]; or polyclonal 1875, generous gift from G. Brewer [University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, Piscataway] and Upstate Biotechnology, St Quentin en Yvelines, France), anti-HuR (monoclonal 3A2, a generous gift from I. Gallouzi, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada), anti-ALK1 or anti-ALKc (a generous gift from Dr B. Falini, Institute of Hematology, University of Perugia, Italy), or antiphosphotyrosine (PY-Plus; Zymed Laboratories, Invitrogen). As a secondary antibody, a goat anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated IgG (GAM PO; Promega) or a goat antirabbit (GAR PO; DAKO, Trappes, France) was used. The signal was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham).

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM EGTA, 1 mM orthovanadate [Na3VO4], 10 mM benzamidine, 1% NP-40, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL pepstatin, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1 mM PMSF) and kept at 4°C under rotation for 30 minutes. Lysates were precleared and, after centrifugation, were incubated at 4°C for 2 hours with monoclonal anti-ALK1, anti-PY, or anti-AUF1 antibody coupled to protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham). After centrifugation, immunocomplexes were washed 3 times with the lysis buffer and boiled in sample buffer. For 2D Western blot analysis of AUF1 immunoprecipitates, 700 μg of proteins extracted from pcDNA3- or NPM-ALK-transfected cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with monoclonalAUF1 antibody; washed immunoprecipitates were solubilized, loaded onto immobiline strips (pH 3-10, 11 cm; Amersham), focused with the IPFGPHOR Isoelectric focusing system (Amersham) and subjected simultaneously to SDS-PAGE with a Multiphor II electrophoresis unit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham).

Proteomic and mass spectrometry analyses

Anti-ALK immunoprecipitates from SU-DHL1 and FEPD ALCL cells were separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and visualized using colloidal blue staining. Excised bands were digested with modified trypsin (Promega). Peptide mass fingerprinting was carried out by using a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer (Voyager DE STR; Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) on each protein band. Unknown proteins were identified using the database-fitting program MS-Fit (Protein Prospector; http://prospector.ucsf.edu). Mass accuracy of 10 ppm was obtained with internal calibration using autodigestion peaks of trypsin (M+H+, 842.51, 2211.10, and 2283.18).

RNase protection assay and riboprobes

The mCYC-1 mouse cyclin multiprobe template set (BD Pharmingen, Pont de Claix, France) was used to synthesize high-specific-activity α-32P-labeled antisense RNA probes which were hybridized with 20 μg of RNA extracted from transfected NIH3T3 cells. A c-myc-radiolabeled probe was also synthesized and used in parallel with the L32 probe. Ribonuclease protection assay (RPA) was performed following BD Pharmingen's instructions.

Results

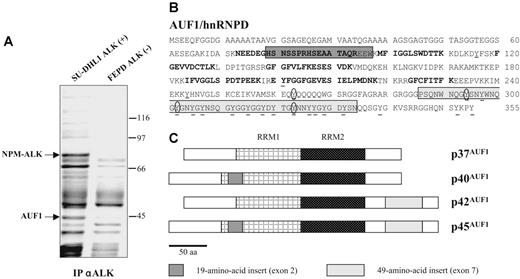

AUF1 is a partner of ALK

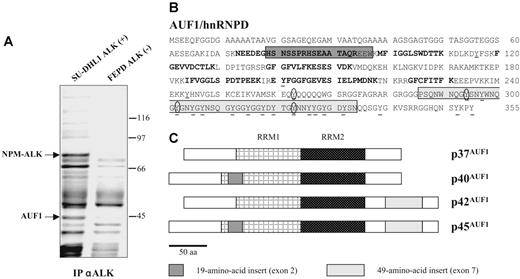

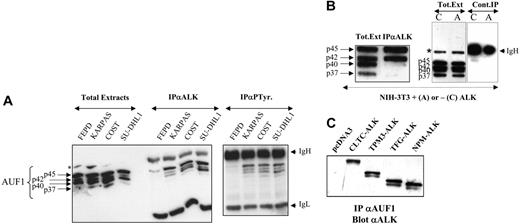

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying ALK-induced oncogenesis in ALCLs, a mass spectrometric analysis of ALK-containing immunoprecipitates was undertaken using the NPM-ALK-positive SU-DHL1 line29 and the ALK-negative FEPD line30 as a control. Proteins immunoprecipitated with the anti-ALK1 monoclonal antibody were resolved by SDS-PAGE analysis. In addition to several known partners of NPM-ALK (results not shown and Crockett et al20 ), we observed a protein that was only present in the immunoprecipitate (IP) from NPM-ALK-positive SU-DHL1 cell line (Figure 1A) and that we identified after analysis of 10 peptides by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (“Materials and methods”) as AUF1/hnRNPD (Figure 1B). AUF1 proteins comprise 4 isoforms, p37AUF1, p40AUF1, p42AUF1, and p45AUF1 (Figure 1C), which vary according to the presence or absence of N-terminal 19 (exon 2)- and C-terminal (exon 7) 49-amino acid-long inserts, resulting from alternative splicing of the same pre-mRNA.32 The molecular weight data together with the fact that 1 peptide overlapped exon 2 (Figure 1B) indicated that, of the 4 AUF1 isoforms, p45AUF1 was predominantly associated with NPM-ALK. The joint presence of AUF1 and NPM-ALK in the same complex was confirmed by ALK immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis, not only in SU-DHL1 cells but also in 2 other NPM-ALK-positive cell lines, COST33 and Karpas 29925 (Figure 2A). Similarly, the use of an antiphosphotyrosine antibody led to the coimmunoprecipitation of AUF1 (anti-P-Tyr; Figure 2A), mainly in the NPM-ALK-expressing ALCL. This indicates either that the

degree of AUF1 phosphorylation on tyrosine residues is higher in NPM-ALK-expressing cells than in the control FEPD cells or that the association of AUF1 with protein(s) recognized by the anti-P-Tyr antibody requires NPM-ALK expression (see Figure 3 and “Discussion”).

AUF1/hnRNPD is an ALK partner. (A) ALK-associated proteins were immunoprecipitated from ALK-positive SU-DHL1 and control FEPD cell lines using anti-ALK (ALK1) antibody. The band labeled AUF1, whose intensity was clearly different in NPM-ALK-positive and -negative protein extracts, was identified by proteomic and mass spectrometry analyses as p45AUF1. (B) Peptide sequence of AUF1. Bold type indicates the peptides used to identify AUF1 (31% recovery). The 2 alternative exons (2 and 7) are boxed. Seven tyrosine residues, common to all 4 isoforms, are found in the core of AUF1, and 14 are located in the alternative carboxy-terminal sequence encoded by exon 7, found in p42AUF1 and p45AUF1 isoforms. Except for tyrosine 244 (numbered according to the human sequence), found only in rat, mouse, and human AUF1 proteins, all these tyrosine residues are present in chicken and Xenopus AUF1 proteins. The conserved tyrosine residues are underlined and those predicted to be efficiently phosphorylated31 (score > 0.6) are encircled. (C) AUF1 protein contains 2 RNA recognition motifs (RRM1, RRM2) and comprises 4 isoforms, p37AUF1, p40AUF1, p42AUF1, and p45AUF1, depending on the presence or absence of the 19-amino acid N-terminal and/or 49-amino acid C-terminal inserts.

AUF1/hnRNPD is an ALK partner. (A) ALK-associated proteins were immunoprecipitated from ALK-positive SU-DHL1 and control FEPD cell lines using anti-ALK (ALK1) antibody. The band labeled AUF1, whose intensity was clearly different in NPM-ALK-positive and -negative protein extracts, was identified by proteomic and mass spectrometry analyses as p45AUF1. (B) Peptide sequence of AUF1. Bold type indicates the peptides used to identify AUF1 (31% recovery). The 2 alternative exons (2 and 7) are boxed. Seven tyrosine residues, common to all 4 isoforms, are found in the core of AUF1, and 14 are located in the alternative carboxy-terminal sequence encoded by exon 7, found in p42AUF1 and p45AUF1 isoforms. Except for tyrosine 244 (numbered according to the human sequence), found only in rat, mouse, and human AUF1 proteins, all these tyrosine residues are present in chicken and Xenopus AUF1 proteins. The conserved tyrosine residues are underlined and those predicted to be efficiently phosphorylated31 (score > 0.6) are encircled. (C) AUF1 protein contains 2 RNA recognition motifs (RRM1, RRM2) and comprises 4 isoforms, p37AUF1, p40AUF1, p42AUF1, and p45AUF1, depending on the presence or absence of the 19-amino acid N-terminal and/or 49-amino acid C-terminal inserts.

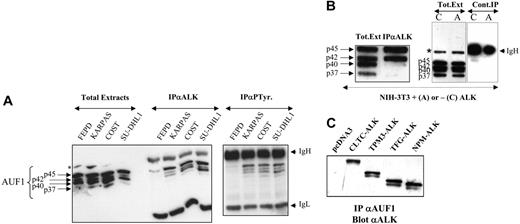

AUF1 and ALK are found in the same complex. (A) Total proteins (Total Extracts; 5 μg) extracted from NPM-ALK-negative FEPD and -positive Karpas 299, COST, and SU-DHL1 cells were run in parallel with proteins (200 μg) immunoprecipitated with anti-ALK1 (IPαALK) or antiphosphotyrosine (IPαP-Tyr) antibody. The membranes were probed with the anti-AUF1 monoclonal antibody, revealing the presence of different AUF1 isoforms contained in the NPM-ALK complex or linked to phosphotyrosine-containing proteins. IgH and IgL indicate the migration of the heavy and light chains of Ig, respectively. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific protein cross-reacting with the anti-AUF1 monoclonal antibody. (B) Total proteins (Tot. Ext; 5 μg) extracted from NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells were run in parallel with proteins (400 μg) immunoprecipitated with anti-ALKc (IPαALK). Control experiments were also performed using NMP-ALK-expressing (“A”) or control cells (“C”) to test for nonspecific AUF1 binding to the IgG1-Sepharose A column (Cont.IP). IgH and asterisk as in panel A. (C) Proteins (400 μg) extracted from NIH3T3 cells stably transfected either with the empty pcDNA3 vector or with different X-ALK fusion cDNAs, as indicated, were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-AUF1 antibody. The presence of ALK protein in the IP was revealed by Western blot analysis using anti-ALK (ALKc) antibody.

AUF1 and ALK are found in the same complex. (A) Total proteins (Total Extracts; 5 μg) extracted from NPM-ALK-negative FEPD and -positive Karpas 299, COST, and SU-DHL1 cells were run in parallel with proteins (200 μg) immunoprecipitated with anti-ALK1 (IPαALK) or antiphosphotyrosine (IPαP-Tyr) antibody. The membranes were probed with the anti-AUF1 monoclonal antibody, revealing the presence of different AUF1 isoforms contained in the NPM-ALK complex or linked to phosphotyrosine-containing proteins. IgH and IgL indicate the migration of the heavy and light chains of Ig, respectively. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific protein cross-reacting with the anti-AUF1 monoclonal antibody. (B) Total proteins (Tot. Ext; 5 μg) extracted from NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells were run in parallel with proteins (400 μg) immunoprecipitated with anti-ALKc (IPαALK). Control experiments were also performed using NMP-ALK-expressing (“A”) or control cells (“C”) to test for nonspecific AUF1 binding to the IgG1-Sepharose A column (Cont.IP). IgH and asterisk as in panel A. (C) Proteins (400 μg) extracted from NIH3T3 cells stably transfected either with the empty pcDNA3 vector or with different X-ALK fusion cDNAs, as indicated, were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-AUF1 antibody. The presence of ALK protein in the IP was revealed by Western blot analysis using anti-ALK (ALKc) antibody.

To further investigate the unexpected association between AUF1 and NPM-ALK in a less genetically variable system than ALCLs, we used the murine NIH3T3 fibroblastic cell line, which acquires transformed properties upon stable expression of NPM-ALK.19 Again, NPM-ALK and AUF1 coprecipitated in anti-ALK IP. p45AUF1 and p42AUF1, the most abundant isoforms in these cells, predominated in the complex (Figure 2B). A control experiment using irrelevant IgG1 confirmed that there was no non-specific binding of AUF1 to the protein A-Sepharose column.

To determine whether the presence of AUF1 in the complex was dependent on the ALK portion of the fusion protein, we used stably transfected NIH3T3 cells expressing various X-ALK fusion proteins, CLTC-ALK, TPM3-ALK, TFG-ALK, or NPM-ALK, which also show transforming capacities.19 Regardless of the ALK fusion protein expressed, ALK was always present in the anti-AUF1 IP (Figure 2C) and vice versa (Figure 2B for NPM-ALK and results not shown for the other fusion proteins). Taken together, these results show that AUF1 and ALK belong to the same complex and that their association depends on the ALK portion and not on the chimeric partner protein moiety.

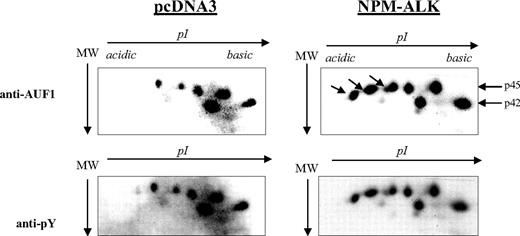

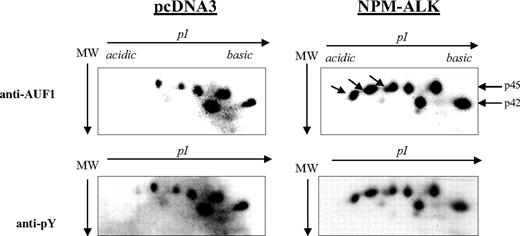

AUF1 is phosphorylated upon ALK expression

AUF1 contains numerous tyrosine residues (Figure 1B) and is thus a potential substrate for ALK tyrosine kinase. Therefore, we decided to see whether NPM-ALK could phosphorylate AUF1. We constructed GST-p37AUF1, GST-p40AUF1, GST-p42AUF1, and GST-p45AUF1 fusion proteins and used them in an in vitro kinase assay with the kinase portion of the NPM-ALK protein. Other than the autophosphorylation of the kinase, we observed the phosphorylation of all 4 AUF1 isoforms, indicating that they are indeed substrates of ALK in vitro (data not shown). We then wished to determine whether AUF1 was a substrate of NPM-ALK in vivo using control (pcDNA3) and NPM-ALK-transfected NIH3T3 cells. AUF1 was first immunoprecipitated from each cell extract with an anti-AUF1 antibody and the IPs were then simultaneously analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis. p45AUF1 and p42AUF1, which were the most abundant isoforms in the IP, were resolved into several spots corresponding to charge differences. Several more negatively charged variants of AUF1 were observed in NPM-ALK-positive cells (arrow in Figure 3). These and the other spots were recognized by the anti-P-Tyr antibody (αpY). These results indicate that AUF1 is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues under basal conditions and that NPM-ALK expression leads to addition of phosphate groups, either to tyrosine or threonine/serine residues (“Discussion”). All together, our results indicate that NPM-ALK is complexed with AUF1 and enhances its phosphorylation.

Hyperphosphorylation of AUF1 in NPM-ALK-expressing cells. Proteins were extracted from pcDNA3 and NPM-ALK-transfected NIH3T3 cells, and 700 μg were immunoprecipitated with the monoclonal anti-AUF1 antibody. The IPs were subjected to 2D gel analysis; after transfer, the nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with anti-AUF1 antibody (time of exposure, 1 minute), carefully stripped, and hybridized with secondary peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse antibody (GAM PO); no signal was observed after 15 minutes of exposure, indicating that no more antibodies were bound to the membrane (data not shown). The membrane was then stripped again and probed with antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pY) antibody (time of exposure, 2 minutes). The hyperphosphorylated AUF1 variants differentially expressed between control and NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells are shown by arrows.

Hyperphosphorylation of AUF1 in NPM-ALK-expressing cells. Proteins were extracted from pcDNA3 and NPM-ALK-transfected NIH3T3 cells, and 700 μg were immunoprecipitated with the monoclonal anti-AUF1 antibody. The IPs were subjected to 2D gel analysis; after transfer, the nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with anti-AUF1 antibody (time of exposure, 1 minute), carefully stripped, and hybridized with secondary peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse antibody (GAM PO); no signal was observed after 15 minutes of exposure, indicating that no more antibodies were bound to the membrane (data not shown). The membrane was then stripped again and probed with antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pY) antibody (time of exposure, 2 minutes). The hyperphosphorylated AUF1 variants differentially expressed between control and NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells are shown by arrows.

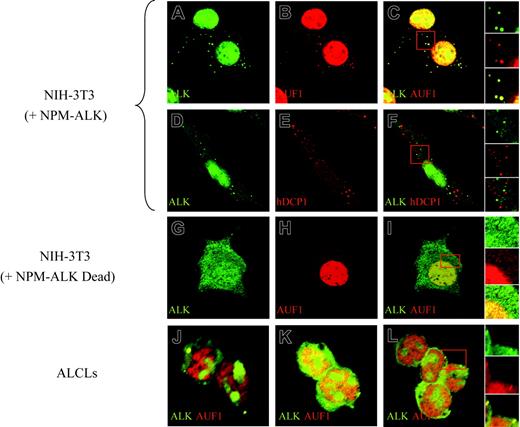

AUF1 and NPM-ALK colocalize in cytoplasmic foci

To further investigate the association of AUF1 and NPM-ALK, we analyzed their cellular localization by immunofluorescence. Apart from their expected high level of expression in the nucleus (NPM-ALK being found in the nucleoli, while AUF1 is excluded from this compartment), both proteins were found concentrated in large foci (0.8-1.5 μm in diameter) in the cytoplasm of NPM-ALK-expressing cells. The foci, where NPM-ALK and AUF1 perfectly colocalized, were observed in NPM-ALK NIH3T3 cells (Figure 4C and right insert) as well as in Karpas (Figure 4J), SU-DHL1 (Figure 4K) and COST cells (Figure 4L and right insert). They were not found in NIH3T3 cells expressing a kinase-defective version of NPM-ALK (Dead)11 (Figure 4G-I). These cytoplasmic granules were reminiscent of processing bodies (P-bodies) that are the sites of mRNA degradation in yeast34 and mammals.26,27 To ascertain whether NPM-ALK and AUF1 colocalized within these structures, we used Dcp1a, which is an established marker of P-bodies.34 The results of double IF labeling using anti-NPM-ALK and anti-hDCP1a antibodies showed both proteins to be present in discrete foci (Figure 4D, ALK; and Figure 4E, hDcp1), which, as shown by the merged view, were essentially nonoverlapping in NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 (Figure 4F and right insert) and ALCL-derived cells (results not shown). Taken together, our biochemical and IF data demonstrate that NPM-ALK and AUF1 are found associated within the same complexes and that they colocalize in cytoplasmic foci in NPM-ALK-expressing cells.

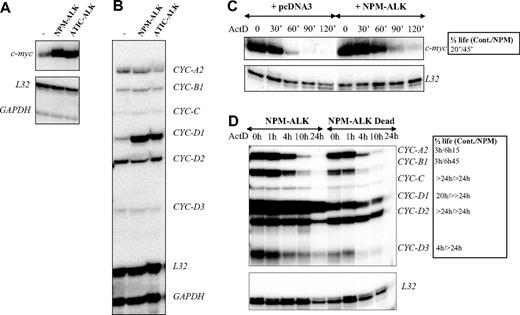

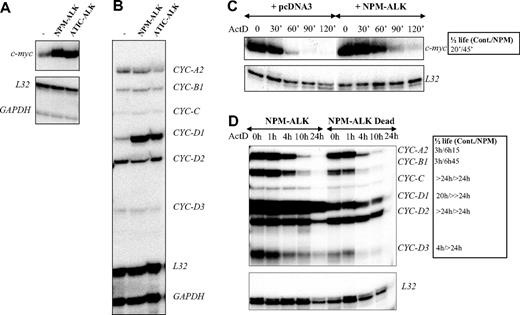

Increased stability of ARE-containing mRNAs in ALK-expressing cells

AUF1 is a ubiquitously expressed hnRNP containing 2 RNA recognition motif (RRM) repeats through which it binds to ARE-containing mRNAs and regulates their turnover rates.35 In the light of recent findings showing that posttranslational modifications of AU-BPs may be critical for regulating ARE-mRNA turnover rates,36-39 we hypothesized that ALK-triggered hyperphosphorylation of AUF1 might influence its function. To test this, we used an RNAse protection assay to compare the level of expression of various ARE-containing mRNAs previously described to be AUF1 targets, including c-myc and several cyclin mRNAs,35,40,41 in control or ALK-transformed NIH3T3 cells (NPM-ALK or ATIC-ALK). As control cells, we used NIH3T3 cells stably transfected with a pcDNA3 vector or expressing the kinase-defective NPM-ALK mutant (Dead). We reproducibly observed a 3- to 5-fold increase in c-myc and cyclin D1 mRNA levels in NPM-ALK-expressing cells (Figure 5A-B), which was correlated with enhanced mRNA stability, as measured by standard actinomycin D (ActD) chase analysis (Figure 5C-D). We also observed increased half-life of cyclins A2, B1, and D3 mRNA in ALK-expressing cells (Figure 5D, and data not shown for an independently performed experiment).

NPM-ALK and AUF1 colocalize in cytoplasmic granules. Permeabilized NPM-ALK NIH3T3 and ALCL-derived cells were incubated with monoclonal anti-ALK and/or polyclonal anti-AUF1 or hDCP1 serum, as indicated. AUF1 and NPM-ALK are found in cytoplasmic foci (A-B) that fully colocalize (panel C and magnification of the insert in the right panels). These cytoplasmic foci do not correspond to P-bodies recognized by a polyclonal anti-hDCP1 serum (E), as NPM-ALK-labeled granules (D) and P-bodies (E) do not overlap (panel F and magnification of the insert in the right panel insert). NPM-ALK tyrosine kinase activity is required for granule formation, as granules are not observed in NIH3T3 cells expressing a NPM-ALK kinase-defective mutant (G-I). Colocalization of NPM-ALK and AUF1 is also observed in NPM-ALK-expressing ALCL-derived cells (Karpas, panel J; SU-DHL1, panel K; and COST, panel L and magnification of the insert in the right panel).

NPM-ALK and AUF1 colocalize in cytoplasmic granules. Permeabilized NPM-ALK NIH3T3 and ALCL-derived cells were incubated with monoclonal anti-ALK and/or polyclonal anti-AUF1 or hDCP1 serum, as indicated. AUF1 and NPM-ALK are found in cytoplasmic foci (A-B) that fully colocalize (panel C and magnification of the insert in the right panels). These cytoplasmic foci do not correspond to P-bodies recognized by a polyclonal anti-hDCP1 serum (E), as NPM-ALK-labeled granules (D) and P-bodies (E) do not overlap (panel F and magnification of the insert in the right panel insert). NPM-ALK tyrosine kinase activity is required for granule formation, as granules are not observed in NIH3T3 cells expressing a NPM-ALK kinase-defective mutant (G-I). Colocalization of NPM-ALK and AUF1 is also observed in NPM-ALK-expressing ALCL-derived cells (Karpas, panel J; SU-DHL1, panel K; and COST, panel L and magnification of the insert in the right panel).

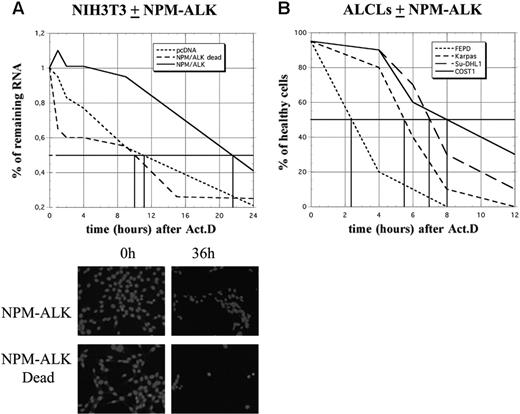

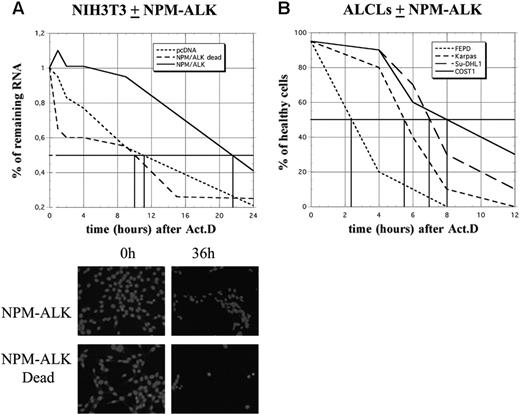

Delayed cell death in NPM-ALK-expressing cells

Analysis of cyclin mRNA half-lives required a longer period of analysis. Strikingly, while more than 50% of control (pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK Dead) cells were dead after 12 hours of ActD treatment, more than 80% of NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells remained healthy at this time and almost one-third had survived at 36 hours, as determined by nuclear DAPI staining (Figure 6A). Furthermore, in ALCL-derived cells, approximately 50% of FEPD cells were dead 2 hours after treatment, while cell death in Karpas, SU-DHL1, and COST cells occurred 3 to 5 hours later, Karpas cells being the least resistant (Figure 6B). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that NPM-ALK acts on a posttranscriptional level by enhancing mRNA stability, which in turn protects cells from death.

Increased stability of c-myc and cyclin mRNAs in ALK-expressing cells. (A-B) Total RNAs were extracted from control (pcDNA3) (-), NPM-ALK-, or ATIC-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells and used in an RNAse protection assay to compare levels of expression of c-myc and cyclin mRNAs. c-myc riboprobe (A) or cyclin multiprobe template set (B) were used simultaneously with L32 and GAPDH riboprobes, which served as controls for RNA loading. (C-D) Actinomycin D was added at 0 time to control (pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK Dead) or NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells. RNAse mapping analysis was performed as in panels A-B. c-myc and cyclin mRNA half-lives in control (Cont.: pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK Dead) and NPM-ALK-expressing cells were calculated from RNAse protection assay data shown in panels C-D. > 24 hours means that the mRNA half-life exceeds 24 hours but could not be calculated precisely, because of the extensive cell death that occurred after this time point.

Increased stability of c-myc and cyclin mRNAs in ALK-expressing cells. (A-B) Total RNAs were extracted from control (pcDNA3) (-), NPM-ALK-, or ATIC-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells and used in an RNAse protection assay to compare levels of expression of c-myc and cyclin mRNAs. c-myc riboprobe (A) or cyclin multiprobe template set (B) were used simultaneously with L32 and GAPDH riboprobes, which served as controls for RNA loading. (C-D) Actinomycin D was added at 0 time to control (pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK Dead) or NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells. RNAse mapping analysis was performed as in panels A-B. c-myc and cyclin mRNA half-lives in control (Cont.: pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK Dead) and NPM-ALK-expressing cells were calculated from RNAse protection assay data shown in panels C-D. > 24 hours means that the mRNA half-life exceeds 24 hours but could not be calculated precisely, because of the extensive cell death that occurred after this time point.

Discussion

Numerous studies have been aimed at understanding how ARE-binding proteins assemble on a given ARE and how they interact with auxiliary proteins to form various complexes which influence mRNA localization, (de)stabilization, or translation. Not only does the abundance of a given AU-BP vary from cell to cell, but its affinity toward AREs depends on the type and functional state of the cell under analysis.42 Several pathways involving mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), such as MAPK p38, MAPK p42/p44, MAPK c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) have been implicated in the stabilization of ARE-containing mRNAs.36,43-49 How the triggering of these signaling pathways results in modulation of ARE-containing mRNAs remains poorly understood. However, recent findings indicate that some ARE-binding proteins may be posttranslationally modified in response to both extracellular stimuli and internally generated signals. Posttranslational modifications of AU-BPs, including methylation,50 ubiquitinylation,51,52 and phosphorylation,35,37,53-55 may be critical for regulating ARE-mRNA turnover rates. In the present study, we show that AUF1, an mRNA-binding protein involved in the control of ARE-containing mRNA stability, is a substrate of the NPM-ALK oncogenic tyrosine kinase. Their partnership leads to AUF1 hyperphosphorylation, which is correlated with changes in stability of several labile AUF1-target mRNAs encoding proteins whose deregulation can lead to oncogenesis.

NPM-ALK expression protects cells from death. (A) Schematic representation of cell survival after actinomycin D treatment in control (pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK dead) or NPM-ALK-transfected NIH3T3 cells. Total RNA was extracted at different times after ActD treatment (1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 15, and 24 hours), quantified, and expressed relative to the amount of RNA found in untreated (0 hours) cells, arbitrarily expressed as 1. The vertical bars indicate the time at which 50% of the starting amount of RNA was recovered in the different cell lines (10 hours in control cells, 22 hours in NPM-ALK-expressing cells). The cells were also fixed and stained with DAPI for counting and to determine their viability. Shown are representative images of NIH3T3 cells expressing NPM-ALK or the mutated dead variant 0 hours and 36 hours after ActD. (B) At different times after ActD treatment, the different ALCL-derived cell lines were stained with trypan blue and counted in a hematocytometer. The ratios between healthy and dead cells were determined.

NPM-ALK expression protects cells from death. (A) Schematic representation of cell survival after actinomycin D treatment in control (pcDNA3 or NPM-ALK dead) or NPM-ALK-transfected NIH3T3 cells. Total RNA was extracted at different times after ActD treatment (1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 15, and 24 hours), quantified, and expressed relative to the amount of RNA found in untreated (0 hours) cells, arbitrarily expressed as 1. The vertical bars indicate the time at which 50% of the starting amount of RNA was recovered in the different cell lines (10 hours in control cells, 22 hours in NPM-ALK-expressing cells). The cells were also fixed and stained with DAPI for counting and to determine their viability. Shown are representative images of NIH3T3 cells expressing NPM-ALK or the mutated dead variant 0 hours and 36 hours after ActD. (B) At different times after ActD treatment, the different ALCL-derived cell lines were stained with trypan blue and counted in a hematocytometer. The ratios between healthy and dead cells were determined.

We first describe the association between AUF1 and ALK in various cell types, including human cell lines derived from (2;5)(p23;q35) ALCLs or murine NIH3T3 cell lines expressing different X-ALK fusion proteins. We show that AUF1 and ALK association requires the ALK portion of the X-ALK fusion protein. Interestingly, colocalization of these proteins was observed in large cytoplasmic granules which, although resembling P-bodies, did not contain Dcp1, a hallmark of these structures.26,56 Formation of these cytoplasmic foci, which have recently been described in Karpas 299 cells,57 requires ALK kinase activity, since they were not observed in NIH3T3 cells expressing the kinase-dead NPM-ALK (K210R) mutant. The nature and the components of these structures are currently under characterization.

In the absence of appropriate antibodies, it is difficult to ascertain which AUF1 isoform(s) is present in the cytoplasmic foci. However, mass spectrometric analysis and immunoprecipitation data clearly indicate that p45AUF1 is reproducibly found associated with NPM-ALK in murine and human cell lines. The other isoforms are also present, but their amount is variable from cell to cell. For instance, although the p45AUF1 and p40AUF1 isoforms are expressed at similar levels in Karpas and SU-DHL1 cells, more p40AUF1 is associated with NPM-ALK in SU-DHL1. As AUF1 isoforms are able to oligomerize,58,59 these differences may be linked to the composition of the oligomers formed.

Association of NPM-ALK with AUF1 isoforms resulted in their increased phosphorylation on tyrosine residues. This was observed in NIH3T3 cells as well as in ALCL-derived cell lines, where more negatively charged forms were specifically found in NPM-ALK-expressing cells. These variants were recognized by the antiphosphotyrosine antibody, suggesting that they contained additional phosphates on tyrosine residues. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that ALK can phosphorylate the 4 isoforms in vitro (not shown). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that these phosphorylated forms have also acquired additional phosphates on serine or threonine residues, as recently reported.39,60 Further experiments are needed to map the residues phosphorylated following constitutive activation of NPM-ALK.

The hyperphosphorylation of AUF1 observed in NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells correlated with increased expression of several mRNA, particularly ARE-containing mRNAs which have been shown to interact with AUF1, namely c-myc and cyclins A2, B1, and D1.35,40,41 Our data are consistent with previous observations in rat 1A fibroblasts, where expression of NPM-ALK induced marked up-regulation of cyclin A and cyclin D1 expression and elevated expression of several immediate early genes involved in cellular proliferation, including fos, jun, and c-myc,61 all known to contain AREs in their mRNAs. Moreover, coexpression of c-Myc and ALK was observed in ALK-positive, but not in ALK-negative, T-cell lymphoma.62 Cyclin D3 was also recently shown to be overexpressed in ALK+ compared with ALK- ALCL.63 Comparative sequence analysis of the mammalian cyclin D3 3′ untranslated region (UTR; not shown) reveals a conserved AU-rich sequence, including the AUUUAAUUUUU sequence, which may be a potent binding site for AU-BPs. Using ActD, we demonstrated that increased level of expression of cyclin D3 mRNA, as well as that of c-myc and cyclins A2, B1, and D1, in NPM-ALK-expressing NIH3T3 cells was largely due to their increased stability.

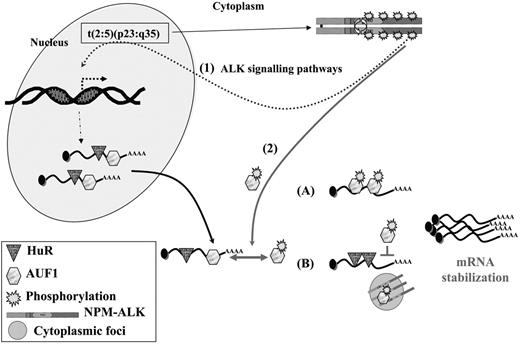

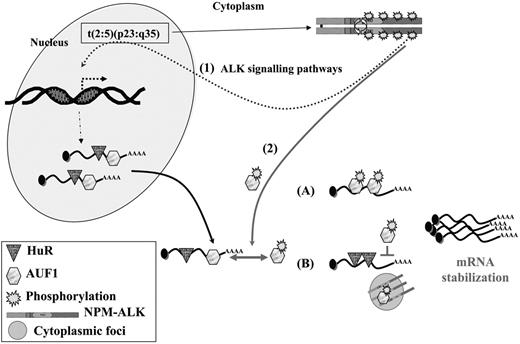

Interestingly, together with the decreased turnover of these mRNAs (and possibly of other short-lived mRNAs that remain to be characterized) we found that the NPM-ALK-positive cells survived longer than control cells after ActD treatment. This result was observed in NIH3T3 cells and also in several human NPM-ALK ALCL-derived cells. However, we noticed that Karpas cells were reproducibly more sensitive to ActD treatment than SU-DHL1 or COST cells. The different patterns of phosphotyrosine-containing proteins found in NPM-ALK ALCLs, as well as the biochemical differences already noted between SU-DHL1 and Karpas cells,57,64 possibly account for the different delays observed. Our study thus brings to light a neglected aspect of NPM-ALK (ie, its activity at the level of mRNA stability). In addition to up-regulating the transcription of several genes via activation of various signaling pathways, NPM-ALK expression leads to decreased turnover of ARE-containing mRNA. Several possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive, can be envisaged (Figure 7). Following interaction with NPM-ALK or other tyrosine kinases complexed with NPM-ALK, such as pp60c-src,16 AUF1 phosphorylation is increased and the protein acquires new properties with respect to its target ARE mRNAs. This hypothesis is supported by several recent data showing that phosphorylation modifies the RNA-binding properties of various AU-BPs,55 including AUF1, in which phosphorylation of serine residues contained in p40AUF1 exon 238 or of threonine residues60 influences ARE binding. Depending on whether AUF1 is viewed as a stabilizing40,65 or destabilizing factor,22,35 its hyperphosphorylation may respectively increase or decrease its affinity for ARE (Figure 7). It is also possible that its sequestration within an NPM-ALK complex in cytoplasmic granules favors the assembly of stabilizing AU-BPs on ARE RNAs. This scenario has recently been proposed to explain the increased levels of Pitx2, c-jun, cyclin D1, and cyclin D2 mRNAs triggered by activation of the Wnt signaling pathway: reduced binding of the destabilizing KSRP and TTP AU-BPs and a concomitantly increased binding of HuR to the ARE contained in the 3′ UTR of these mRNAs were observed.66 Similarly, TTP-dependent degradation of ARE mRNAs is inhibited when its association with 14-3-3 is activated by the p38-MAPK/MK2 kinase cascade in RAW 264.7 macrophages.67 Thus, the ability of NPM-ALK to act at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels by increasing the half-life of short-lived mRNAs contributes to cell survival, enhanced proliferation, and tumorigenesis.

In conclusion, the present work shows for the first time that AUF1 interacts with and is posttranslationally modified by an oncogenic tyrosine kinase. The change in the phosphorylation state of AUF1 and its concentration in NPM-ALK-containing cytoplasmic granules are correlated with an increase in the level of expression of several ARE-containing mRNAs. We thus postulate that modification of AUF1 activity or availability through ALK recruitment leads to a decrease in ARE-directed mRNA turnover and contributes to enhanced cellular proliferation and oncogenicity. This novel mechanism, together with well-characterized antiapoptotic signaling pathways activated by NPM-ALK,68 may contribute to malignancy.

A model for NPM-ALK oncogenicity. In t(2:5)(p23:q35) cells, NPM-ALK enhances transcription of target genes (1) through known signaling pathways, including PLCγ, PI3K, and STAT3/5 activation. Some of these up-regulated genes encode ARE-containing mRNAs whose stability involves AU-BPs. In addition, NPM-ALK enhances mRNA stability (2) by inducing hyperphosphorylation of AUF1. Depending on whether AUF1 is a stabilizing or a destabilizing factor, its posttranslational modification respectively either increases (A) or decreases (B) its affinity/binding for its target mRNAs, in either case leading to their increased stability. Decreased affinity of a destabilizing protein might favor the binding of a stabilizing AU-BP, such as HuR, thus contributing to increased stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. The phosphorylated AUF1 form might also be trapped together with NPM-ALK in cytoplasmic granules (B), allowing access of stabilizing HuR to ARE-mRNAs. In conclusion, enhancing transcription and increasing stability of mRNAs encoding for proteins which are key players of cell proliferation are 2 facets of NPM-ALK activity which both contribute to its oncogenicity.

A model for NPM-ALK oncogenicity. In t(2:5)(p23:q35) cells, NPM-ALK enhances transcription of target genes (1) through known signaling pathways, including PLCγ, PI3K, and STAT3/5 activation. Some of these up-regulated genes encode ARE-containing mRNAs whose stability involves AU-BPs. In addition, NPM-ALK enhances mRNA stability (2) by inducing hyperphosphorylation of AUF1. Depending on whether AUF1 is a stabilizing or a destabilizing factor, its posttranslational modification respectively either increases (A) or decreases (B) its affinity/binding for its target mRNAs, in either case leading to their increased stability. Decreased affinity of a destabilizing protein might favor the binding of a stabilizing AU-BP, such as HuR, thus contributing to increased stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. The phosphorylated AUF1 form might also be trapped together with NPM-ALK in cytoplasmic granules (B), allowing access of stabilizing HuR to ARE-mRNAs. In conclusion, enhancing transcription and increasing stability of mRNAs encoding for proteins which are key players of cell proliferation are 2 facets of NPM-ALK activity which both contribute to its oncogenicity.

Further studies aimed at analyzing precisely the interaction between AUF1 and ALK and the amino acid residues phosphorylated may lead to new therapeutic approaches for the treatment of ALK-expressing lymphomas. Moreover, if the partnership between AUF1 and ALK turns out to be applicable to other AU-BPs and kinases, the study of impaired mRNA stability could constitute an important breakthrough in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of hematopoietic malignancies.

Prepublished online July 11, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014902.

Supported by Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC) contracts no. 9842 and 4794, the Alliance pour les Recherches sur le Cancer (ARECA) network Pôle protéomique et Cancer, the Cancéropole grand Sud-Ouest, and the Conseil Régional “Cibles thérapeutiques et recherche de nouveaux marqueurs diagnostics et pronostics dans les cancers,” as well as the Génopole Toulouse Midi-Pyrénées (B.M.). M.F. is supported by MRT (Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie).

M.F., F.A., S.O., and H.D. performed experimental procedures; C.T. contributed cell lines and analyzed data; B.M. discovered the association between ALK and AUF1; and G.D., B.P., and D.M. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

M.F. and F.A. contributed equally to the work.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank J. Auriol, C. Pichereaux, and F. Capilla for their technical assistance; S. W. Morris for NPM-ALK cDNA; and R.-Y. Bai for NPM-ALK Dead cDNA. This study was also performed with the help of the “Experimental histopathology platform” of IFR30. We are grateful to J. Smith, J. Batut, C. Babinet, N. Vanzo, and C. Moroni for discussion and helpful comments.