Abstract

The source and significance of bloodborne tissue factor (TF) are controversial. TF mRNA, protein, and TF-dependent procoagulant activity (PCA) have been detected in human platelets, but direct evidence of TF synthesis is missing. Nonstimulated monocyte-free platelets from most patients expressed TF mRNA, which was enhanced or induced in all of them after platelet activation. Immunoprecipitation assays revealed TF protein (mainly of a molecular weight [Mr] of approximately 47 kDa, with other bands of approximately 35 and approximately 60 kDa) in nonstimulated platelet membranes, which also increased after activation. This enhancement was concomitant with TF translocation to the plasma membrane, as demonstrated by immunofluorescence–confocal microscopy and biotinylation of membrane proteins. Platelet PCA, assessed by factor Xa (FXa) generation, was induced after activation and was inhibited by 48% and 76% with anti-TF and anti-FVIIa, respectively, but not by intrinsic pathway inhibitors. Platelets incorporated [35S]-methionine into TF proteins with Mr of approximately 47 kDa, approximately 35 kDa, and approximately 60 kDa, more intensely after activation. Puromycin but not actinomycin D or DRB (5,6-dichloro-1-beta-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole) inhibited TF neosynthesis. Thus, human platelets not only assemble the clotting reactions on their membrane, but also supply their own TF for thrombin generation in a timely and spatially circumscribed process. These observations simplify, unify, and provide a more coherent formulation of the current cell-based model of hemostasis.

Introduction

The best known function of tissue factor (TF) is the initiation of clotting.1–3 TF binds factor VIII/factor VIIa (FVII/VIIa), and the complex TF-VIIa activates FX and FIX.4 TF expresses its maximal procoagulant activity (PCA) when incorporated into phospholipid membranes,5 and its gene disruption is associated with embryonic wasting and lethality.6,7 Inversely, excessive TF function triggers thrombotic disorders. Human TF has been purified,8,9 and its recombinant form is widely used.9 The predicted molecular weight [Mr] for the polypeptide chain of 263 amino acids is approximately 30 kDa, vs approximately 47 kDa for the fully glycosylated protein.10

The presence of circulating, functional TF in hemostasis is controversial. Some authors consider that circulating TF is insufficient to generate a timely hemostatic plug,11 and that clotting would be triggered by vessel-wall TF.12 However, the presence in plasma of clotting factor–derived activation peptides13 denotes a normal ongoing, low-grade thrombin generation, and the contrasting changes in plasma levels of these peptides in patients with FVII and FXI deficiencies suggest that clotting is initiated by a bloodborne or blood-exposed TF-FVIIa pathway.14 Particularly, several studies describe a circulating pool of cell- or microparticle-bound TF, able to start clotting.15–20 If the platelet plug obstructs the interaction of plasma-clotting factors with vascular wall TF,21 some form of bloodborne TF would be needed to start or amplify either the normal hemostasis or the thrombus formation and growth.22

The origin of circulating TF has been extensively investigated. Blood monocytes constitute the major potential source of TF,19–21,23–26 as shown by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation assays and the role played by monocytes in the intravascular clotting of septicemia.27 In contrast, resting monocytes express no functional TF,22 likely because it is in an encrypted, inactive form.24 Monocyte interaction with activated platelets and neutrophils would induce TF decryption or the release of monocyte-derived microparticles carrying the active protein.24 Endothelial cells may express active TF after stimulation28 or during systemic infections.29 Synthesis of TF by neutrophils has been positively reported,30 or suggested,31 but it also has been questioned.32,33

Stimulated human platelets seem to export preformed TF17,34 from alpha granules and open canalicular system17 to the plasma membrane.33 Its origin and functionality are unclear, and platelet-leukocyte interactions seem necessary for its expression.17 Reports communicating that TF is transferred to platelets by monocyte-derived microparticles,19,25 or from both monocytes and granulocytes,35 contrast with studies showing that TF would be transferred from platelets to monocytes.36,37 In summary, the origin and localization of bloodborne TF remain highly debatable.

Protein synthesis by anucleated platelets was reported 2 decades ago,38 but only recently was de novo synthesis of Bcl-3,39 interleukin-1β,40 and PAI-141 by human platelets convincingly demonstrated. Denis et al42 found in human platelets constitutive pre-mRNA and critical factors able to splice it upon activation, generating mature messages and new protein. In this context, Camera et al43 described TF-mRNA and an immunoreactive protein with TF activity in platelets. These findings were recently confirmed and extended.44

The platelet plug is built up at sites of vascular injury, where activated platelets play a major role in localizing and controlling the clotting reactions.45 If functional TF is produced by platelets, the current cell-based model of hemostasis45 has to be redefined. Accordingly, we tested the hypothesis that human platelets synthesize de novo TF.

Materials and methods

The IRB (Medical Ethics Committee) of the School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, approved this research. It was also approved by Fondecyt, the government financing agency. Blood samples from healthy volunteers were obtained after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Platelet isolation

Venous blood (70 mL) was collected from healthy volunteers not taking antiplatelet drugs into EDTA (5 mM, final concentration) or ACD-A (1:10, vol/vol). After centrifugation (10 minutes at 150g), the top two-thirds of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was removed and centrifuged (8 minutes at 1400g). The pellet was washed with buffer (137 mM NaCl, 5.3 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 4.1 mM NaHCO3, and 5.5 mM glucose [pH 6.5]) containing prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) (120 nM). Platelets were centrifuged (150g for 5 minutes) to remove residual leukocytes. The supernatants (2 mL) were placed and centrifuged (2700g for 15 minutes) over 1 mL of 40% bovine serum albumin (BSA; fraction V; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO).46 The platelets above the albumin were washed, centrifuged (1400g for 8 minutes), and finally resuspended in the same buffer. Centrifugations were done at room temperature (RT). Cell counts were performed by contrast microscopy. In control experiments, platelets were kept at 4°C during all the isolation steps after blood drawing. Leukocyte contamination was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy using propidium iodide staining and by flow cytometry with CD45 and CD14 MoAbs (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA). Leukocyte counts were always less than 1/105 platelets. In addition, monocyte contamination was evaluated by amplification of CD14 mRNA by reverse transcriptase–PCR. The experiments were conducted in nonstimulated and stimulated platelets at 37°C for different times with 5 μM TRAP (SFLLRN, thrombin receptor activation peptide; Bachem Bioscience, King of Prussia, PA), 0.5 μg/mL equine collagen (Collagenreagent; Hormonchemie, Munich, Germany), or 2 μM ADP (Sigma-Aldrich). When indicated, platelets were incubated for 30 minutes with Salmonella thyphosa LPS (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). The surface expression of P-selectin attained 8% to 21% of nonstimulated platelets isolated at RT, and more than 80% after TRAP activation (Flow cytometry; BD FACSCalibur, Becton and Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Isolation of PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) suspensions were prepared as described,47 with slight modifications. The buffy coats and erythrocytes were reconstituted to their original volumes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mM EDTA (PBS-EDTA) and layered on a Ficoll/Hypaque column (Histopaque 1077; Sigma-Aldrich), 1:1 vol. After RT centrifugation (200g for 30 minutes), the leukocyte layer was collected, washed twice in PBS-EDTA, centrifuged (150g for 10 minutes) and suspended in PBS-EDTA. PBMCs contained 11% to 20% monocytes (n = 5), which were measured by flow cytometry using CD45 and CD14 MoAbs. CD61 MoAb labeling showed that all the PBMC suspensions contained platelets (1.2%-25.5% of all events).

RNA extraction from platelets and PBMCs

Total RNA was extracted from at least 108 platelets or 106 PBMCs before and after TRAP activation for 15 minutes or for 2 hours with 10 μg/mL Salmonella thyphosa LPS. RNA was isolated using 1 mL TRIzol-LS reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The RNA, dissolved in 20 μL RNAse-free H2O, was incubated (65°C for 10 minutes) and quantified by spectrophotometry (GeneQuant pro; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Reverse transcriptase–PCR

Platelet and PBMC TF mRNA was detected by RT-PCR, using commercial reagents (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Briefly, approximately 1 μg of RNA was incubated with 0.5 μg of oligo dT12-18 (70°C for 10 minutes). Reverse transcription was performed by incubating the sample (50 minutes at 37°C) with 9 μL of reverse transcription master mix containing 5 × First-Strand Buffer (4 μL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 0.1M dithiothreitol (2 μL), 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (2 μL), and 200 U M-MLV (Moloney murine leukemia virus) reverse transcriptase. The reaction was stopped by heating (95°C for 15 minutes). Samples were kept at −20°C until assayed.

Specific primers were designed to amplify mRNA fragments of human TF, β-actin, CD14, and GPIbα. Primer sequences and PCR product lengths48–50 are shown in Table 1. The primers for the first 3 genes were designed to obtain PCR products of different lengths than their gDNA products. The PCR conditions to amplify TF, β-actin, and CD14 were 1 cycle (95°C for 5 minutes) followed by 30 cycles (95°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute), with a final step at 72°C for 10 minutes. For GPIbα, the PCR protocol was similar, but the annealing temperature was 55°C. TF and β-actin cDNA fragments were cloned separately into a pGem-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), sequenced (Sequencer 3100; Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and used as positive control in PCR reactions (GeneAmp PCR System 2700).

SDS-PAGE in 8% gels was performed with 1 μL of actin PCR products and 20 μL of all the other transcripts, and stained with silver nitrate.51 The gels were submerged in acetic acid/ethanol solution (1:200 vol/vol) and microwave-heated (10 seconds) at maximum potency, soaked in 0.18% AgNO3, warmed again for 10 seconds, and rinsed 3 times with water. The gels were gently agitated in developing solution (0.5 mL of 37% formaldehyde, 20 mL of 7.5% NaOH, and 30 mL of twice-distilled water) until the PCR bands were visible, and then kept in 1% acetic acid. PCR products were analyzed using Scion Image for Windows (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD), and normalized against β-actin.

PCA and ELISA measurement of platelet TF

Platelet PCA was measured in nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelet preparations. The initial experiments were done in platelets isolated at RT, but controls were carried out in platelets isolated at 4°C. The suspensions were preincubated in parallel for 1 hour either with 1 mM puromycin or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide; DMSO). Washed platelets (2 × 107) were diluted 1:10 with 50 mM HEPES buffer containing 0.01% BSA and incubated with 1 IU/mL FVIIa for 5 minutes at 37°C. Then, human FX (0.1 IU/mL), CaCl2 (2.5 mM), and chromogenic substrate (0.2 mM, Spectrozyme FXa) were added and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. (Clotting factors and substrate were from American Diagnostica, Stamford, CT). The FXa generated was measured at 405 nm. A standard curve was made with relipidated human recombinant TF (hrTF; Innovin, Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany), considering 1000 AU/mL the activity of 1:100 dilution of the reagent. The Mr of hrTF (30 kDa) was the reference to convert the TF activity in mass equivalence. TF protein in solubilized platelet membranes was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; American Diagnostica).

To assess the TF dependence of FXa generation, assays were performed after 30 minutes of incubation with sheep anti-TF Ab (2 μg/mL; Affinity Biologicals, Ancaster, Ontario, Canada), α-FVIIa MoAb (4 μg/mL; American Diagnostica), corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI; 50 mM), activated protein C (aPC; 2 μg/mL), or IgG fraction of anti-FVIIIc serum (32 μg/mL) purified from a patient with high-titer FVIII inhibitor. Controls also omitted FVIIa in the assay.

Platelet membrane immunoprecipitation, biotinylation, and Western blots of TF

The membranes from 3 × 108 nonstimulated and activated (TRAP, 30 minutes) platelets, obtained as described,52 were suspended in PBS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and 15 mM n-octyl β-glucopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were stored at −80°C when not processed immediately. Solubilized membranes were incubated either with sheep α-TF Ab or with an irrelevant, nonspecific IgG for 2 hours at RT and immunoprecipitated with protein A–sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at RT. The beads were washed with RCD/EDTA buffer (108 mM NaCl, 38 mM KCl, 1.7 mM NaHCO3, 21.2 mM sodium citrate, 27.8 mM glucose, 1.1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, and 2 mM EDTA [pH 6.2]) and placed in 30 μL SDS-PAGE loading buffer under reducing conditions. Proteins were electrotransferred, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes were incubated with α-TF MoAb (made from rTF in Escherichia coli; Affinity Biologicals). Proteins, revealed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–coupled α-mouse IgG (KPL Inc, Gaithersburg, MD), were visualized using Western Lightning Plus Chemiluminescence Reagent (ECL; Perkin Elmer).

Nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets were preincubated (30 minutes at RT) with 5 mM N-hydroxysuccinimido biotin (Sigma-Aldrich) for different times. After washing, platelet membranes were obtained and immunoprecipitated with polyclonal α-TF as described. Proteins were electrophoresed, transferred to PVDF membranes, and revealed with streptavidin-HRP (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark).

Membranes from nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets, with and without preincubation with puromycin (1 mM for 1 hour) were used for Western blotting. Samples were suspended in reducing buffer, separated in 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with the sheep α-TF Ab, then with a rabbit α-sheep Ab, and revealed with an HRP-coupled α-rabbit IgG (KPL Inc). Control hrTF was included in the electrophoresis gel. Preincubation of the α-TF antibody with hrTF for 30 minutes tested the specificity of the assay.

Platelet TF immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Drops of fresh, nonstimulated, and activated platelet (10 μM TRAP plus 2 μg/mL collagen; 2 hours at 37°C), and of resting and LPS-stimulated PBMC (5 hours at RT) suspensions were dried-fixed on glass slides. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with goat serum containing 0.1% BSA and 0.01% gelatin. After overnight incubation at 4°C, platelet TF and GPIbα were immunolabeled (Figure 5 legend), mounted with UltraCruz mounting medium (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and observed under confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert 200 M and LSM 5 Pascal Laser-Scanning Confocal; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). An UPAL SAPO 100×/1.40 objective was used (Olympus immersion oil; Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) and image was acquired with Fluoview 5.0 software and further processed using Microsoft Office Picture Manager 2003 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA).

Metabolic radiolabeling

Platelets (3 × 108 cells) were preincubated (1 hour at RT) with 10 μCi (0.37 MBq) of [35S]-methionine (Perkin Elmer) and stimulated with TRAP or LPS (30 minutes at 37°C). Membranes were immunoprecipitated either with the sheep α-TF Ab or α-TF MoAb (Clone IIID8; American Diagnostica) and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and protein transfer. [35S]-TF was detected by autoradiography. Inhibition experiments included 1 hour of preincubation with actinomycin D (4 μg/mL), RNA polymerase IIinhibitor DRB (5,6-dichloro-1-beta-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole; 100 μM), puromycin (1 mM), tunicamycin (10-40 ng/mL), or vehicle (DMSO) before incubation with [35S]-methionine.39

TF synthesis by PBMCs was assessed by incubating 106 cells with 10 μCi(0.037 MBq) of [35S]-methionine (1 hour at RT). After activation (10 μg/mL LPS for 2 or 5 hours at 37°C), the cells were centrifuged and lysed. After 30 minutes at 4°C, the suspension was centrifuged (18 000g for 15 minutes). Both the supernatant and cell membranes were immunoprecipitated separately, and [35S]-TF was detected by autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD or SE. The Wilcoxon test for paired samples was used to compare the mean values of platelet PCA at different times with each inhibitor. The general linear model with Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons was used to compare the time-courses of the platelet PCA curves after activation, with or without puromycin.

Results

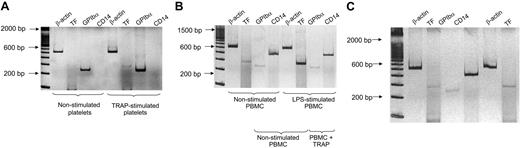

TF mRNA is present in human platelets and is enhanced after activation

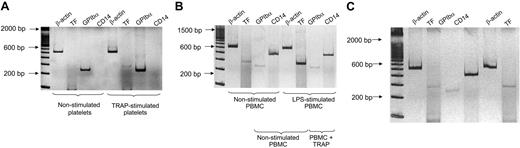

Platelet mRNA amplification is shown in Figure 1A. Abundant platelet-specific GPIbα transcripts were obtained from approximately 1 μg of total mRNA. The lack of transcripts for CD14 mRNA excluded significant monocyte contamination. TF mRNA, although in low quantities, was expressed in 9 of 16 nonstimulated platelet samples. TRAP stimulation induced or increased rapidly (within 15 minutes) the TF mRNA in all samples tested. Collagen or ADP stimulation gave similar results (not shown).

TF mRNA in human platelets and PBMCs. Platelet and PBMC RNAs were extracted before and after stimulation with 5 μM TRAP for 15 minutes. PBMCs were also stimulated for 2 hours with LPS. (A) Amplification of mRNA transcripts in nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets. β-actin represents housekeeping transcripts. In this particular experiment, TF mRNA was detected after TRAP stimulation but not in nonstimulated platelets. The platelet origin of TF mRNA was demonstrated by the amplification of GPIbα mRNA in nonstimulated platelets, by the TF mRNA increase after TRAP activation, and by the lack of transcripts for monocyte CD14 mRNA. (B) PCR amplification of cDNAs of nonstimulated and LPS-stimulated PBMC preparations for 2 hours. CD14 mRNA bands are distinctive of monocytes. TF mRNA was barely detectable in unstimulated PBMCs, although markedly increased after 2 hours of stimulation with LPS. Platelet mRNA in the PBMC suspensions was demonstrated by the observation of GP-1bα amplification in nonstimulated and activated samples. (C) Reverse transcriptase–PCR products of nonactivated and 5 μM TRAP-activated PBMC suspensions. TF mRNA was only slightly enhanced after TRAP stimulation when compared with LPS stimulation in panel B. This mild increase was observed in 3 of 8 experiments, whereas in the remaining 5 experiments, it was unnoticed. Barely visible GPIbα mRNA transcripts were detected, confirming platelet contamination in PBMC preparations. The amplification products were run with a 100-bp ladder in 8% polyacrylamide gel and were silver stained. Negative controls without template showed no amplification products (not shown). gDNA products of β-actin, TF, and CD14 (Table 1) were undetected in all the experiments.

TF mRNA in human platelets and PBMCs. Platelet and PBMC RNAs were extracted before and after stimulation with 5 μM TRAP for 15 minutes. PBMCs were also stimulated for 2 hours with LPS. (A) Amplification of mRNA transcripts in nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets. β-actin represents housekeeping transcripts. In this particular experiment, TF mRNA was detected after TRAP stimulation but not in nonstimulated platelets. The platelet origin of TF mRNA was demonstrated by the amplification of GPIbα mRNA in nonstimulated platelets, by the TF mRNA increase after TRAP activation, and by the lack of transcripts for monocyte CD14 mRNA. (B) PCR amplification of cDNAs of nonstimulated and LPS-stimulated PBMC preparations for 2 hours. CD14 mRNA bands are distinctive of monocytes. TF mRNA was barely detectable in unstimulated PBMCs, although markedly increased after 2 hours of stimulation with LPS. Platelet mRNA in the PBMC suspensions was demonstrated by the observation of GP-1bα amplification in nonstimulated and activated samples. (C) Reverse transcriptase–PCR products of nonactivated and 5 μM TRAP-activated PBMC suspensions. TF mRNA was only slightly enhanced after TRAP stimulation when compared with LPS stimulation in panel B. This mild increase was observed in 3 of 8 experiments, whereas in the remaining 5 experiments, it was unnoticed. Barely visible GPIbα mRNA transcripts were detected, confirming platelet contamination in PBMC preparations. The amplification products were run with a 100-bp ladder in 8% polyacrylamide gel and were silver stained. Negative controls without template showed no amplification products (not shown). gDNA products of β-actin, TF, and CD14 (Table 1) were undetected in all the experiments.

Distinctive monocyte CD14 cDNA expression was found in PBMC preparations, but amplification of GP-Ibα was always observed simultaneously, denoting platelet contamination. A weak TF mRNA band was observed in nonstimulated cells. LPS and TRAP stimulation differed regarding TF mRNA induction: LPS notably and consistently enhanced TF mRNA expression (Figure 1-B) whereas TRAP (Figure 1-C) induced a minor increase in TF mRNA in 3 of 8 experiments. Controls without template demonstrated no amplification (not shown). gDNA products of β-actin, TF, and CD14 (Table 1) were undetected in all the experiments. Two PCR products of TF cDNA from different samples were cloned and sequenced, presenting 99% and 100% identity with the human TF gene, respectively.

PCA of whole platelets is induced with activation and is predominantly dependent upon TF

Nonstimulated platelets isolated at RT exhibited low but consistent PCA, which increased 3-fold after 2 hours of TRAP stimulation. When the isolation procedure took place at 4°C, resting platelets had no detectable PCA, but after stimulation, it attained similar values to those of platelets processed at RT. PCA of TRAP-activated platelets corresponded to the activity generated by approximately 3.6 pM of hrTF. The TF protein measured by ELISA in platelet membranes before TRAP stimulation was 410 ± 257 pg/mg protein (n = 6), equivalent to a concentration of approximately 10.7 in whole platelets. So, 30% to 40% of the immunorecognized TF in platelet membranes could explain all the PCA elicited by TRAP stimulation. Similar results were obtained with other agonists (collagen, ADP). FXa generation was markedly inhibited, although not abolished, by α-TF or α-FVIIa MoAb. The omission of FVIIa in the assay did not alter platelet PCA measurement. α-FVIIIC, aPC, and CTI did not affect significantly the PCA of platelets 2 hours after TRAP activation. Similarly, no inhibitory effect on PCA was observed when platelets were preincubated with puromycin (Figures S1 and S2, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figure link at the top of the online article).

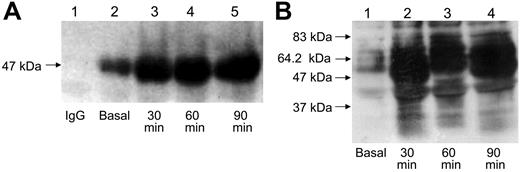

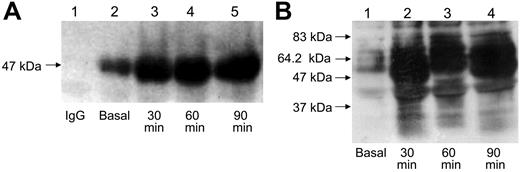

Immunoprecipitation, membrane biotinylation, and immunoblotting assays disclose TF protein in nonstimulated platelets, which augments and translocates to the plasma membrane after platelet activation

Immunoprecipitation assays (Figure 2A) revealed with α-TF MoAb showed an approximately 47-kDa protein in nonstimulated platelets, which increased notably after 30, 60, and 90 minutes of TRAP activation. Resting platelets incubated with biotin and precipitated with polyclonal α-TF showed low TF protein expression on the plasma membrane, which increased strikingly after activation (Figure 2B). α-TF MoAb consistently detected the approximately 47-kDa TF, whereas the sheep α-TF Ab not only disclosed the approximately 47-kDa species, but also other TF-immunoreactive proteins of different Mrs, predominantly of approximately 35 kDa and approximately 60 kDa. Western blots (Figure S3) confirmed the presence of TF in platelets, but also demonstrated that preincubation with puromycin for 60 minutes did not result in a TF decrease, both in nonstimulated and activated platelets, in accordance with the PCA assays. Immunoprecipitation or Western blotting assays in 28 experiments always revealed variable amounts of TF protein in nonstimulated platelets, consistent with the ELISA measurements.

Immunoprecipitation and biotinylation of TF in platelet membranes. (A) Platelet membrane TF in nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets for 30, 60, and 90 minutes was immunoprecipitated with the polyclonal α-TF antibody, and revealed with the α-TF MoAb. A TF band of approximately 47 kDa was detected, which was notably enhanced after activation. Lane 1 shows the lack of reaction when an irrelevant, nonspecific IgG replaced the polyclonal anti-TF antibody. Control hrTF migrated as an approximately 30-kDa major band and a minor band of approximately 60 kDa, and the TF bands disappeared when the anti-TF antibody was quenched with hrTF for 30 minutes before addition to the PVDF membrane, demonstrating the specificity of the reaction (not shown). (B) Resting and activated platelets were incubated with biotin for 30 minutes. The platelet membranes were immunoprecipitated with the polyclonal α-TF, and after electrophoresis and protein transfer, the PVDF membranes were revealed with streptavidin-HRP. Nonstimulated platelets express modest and nondistinctive TF-immunoreactive bands, which are markedly increased after TRAP stimulation.

Immunoprecipitation and biotinylation of TF in platelet membranes. (A) Platelet membrane TF in nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets for 30, 60, and 90 minutes was immunoprecipitated with the polyclonal α-TF antibody, and revealed with the α-TF MoAb. A TF band of approximately 47 kDa was detected, which was notably enhanced after activation. Lane 1 shows the lack of reaction when an irrelevant, nonspecific IgG replaced the polyclonal anti-TF antibody. Control hrTF migrated as an approximately 30-kDa major band and a minor band of approximately 60 kDa, and the TF bands disappeared when the anti-TF antibody was quenched with hrTF for 30 minutes before addition to the PVDF membrane, demonstrating the specificity of the reaction (not shown). (B) Resting and activated platelets were incubated with biotin for 30 minutes. The platelet membranes were immunoprecipitated with the polyclonal α-TF, and after electrophoresis and protein transfer, the PVDF membranes were revealed with streptavidin-HRP. Nonstimulated platelets express modest and nondistinctive TF-immunoreactive bands, which are markedly increased after TRAP stimulation.

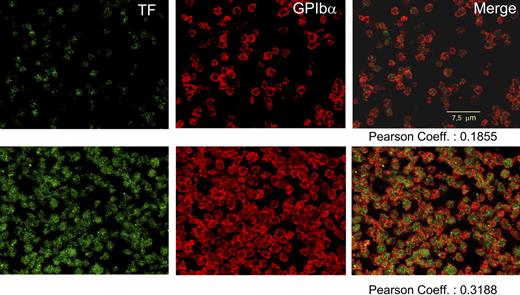

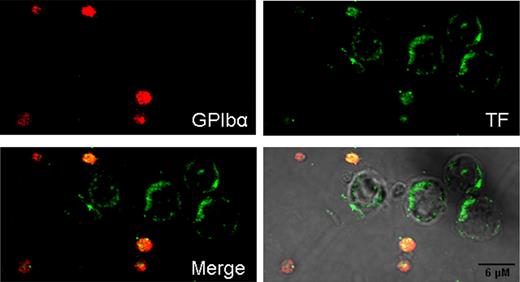

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy show TF-immunoreactive protein in nonstimulated platelets, which augments after platelet activation

Immunofluorescent TF was observed in EDTA-nonstimulated platelets, exhibiting 19% colocalization with GPIbα. The intensity of the label for both proteins increased after stimulation attaining 32% of colocalization (Figure 3). In citrated platelets, more easily activated, the corresponding colocalization values were 21% and 57%.

Confocal immunodetection of TF and GPIbα in human, nonpermeabilized platelets. After fixation, blockade of nonspecific binding sites, and overnight incubation at 4°C, EDTA-PGE1 platelets were immunolabeled with polyclonal anti-TF and/or α-GPIbα (α-CD42b, clone SZ2; Immunotech, Westbrook, ME). For TF, incubation with rabbit anti-sheep IgG was required before incubating with the appropriate FITC antibody. Alexa 555 (Invitrogen) was used to visualize the GPIbα. Top row shows, from left to right: nonstimulated, freshly prepared platelets labeled for TF, GPIbα, and merge imaging. Bottom row shows an aliquot of the same sample stimulated with TRAP and collagen for 2 hours. A striking enhancement of both labels is noticed with a significant increase in the colocalization of both proteins. No leukocytes were observed in all the experiments.

Confocal immunodetection of TF and GPIbα in human, nonpermeabilized platelets. After fixation, blockade of nonspecific binding sites, and overnight incubation at 4°C, EDTA-PGE1 platelets were immunolabeled with polyclonal anti-TF and/or α-GPIbα (α-CD42b, clone SZ2; Immunotech, Westbrook, ME). For TF, incubation with rabbit anti-sheep IgG was required before incubating with the appropriate FITC antibody. Alexa 555 (Invitrogen) was used to visualize the GPIbα. Top row shows, from left to right: nonstimulated, freshly prepared platelets labeled for TF, GPIbα, and merge imaging. Bottom row shows an aliquot of the same sample stimulated with TRAP and collagen for 2 hours. A striking enhancement of both labels is noticed with a significant increase in the colocalization of both proteins. No leukocytes were observed in all the experiments.

Metabolic radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation reveal de novo TF synthesis by human platelets

The autoradiographs showing the immunoprecipitated [35S]-TF from platelet membranes shown in Figure 4A-B are representative of 25 experiments with samples from 18 different individuals. Similar studies were performed in PBMC suspensions (Figure 4C). Description of the findings is given in the corresponding figure legend. Nonstimulated platelets generally expressed newly synthesized TF, more frequently the species of approximately 47-kDa, visible as a band of low to moderate intensity. TRAP as well as LPS stimulation (Figure S4) enhanced the TF synthesis, with or without the appearance of TF proteins of different Mr, mainly of approximately 35 kDa or approximately 60 kDa. Puromycin abolished or substantially inhibited the translation process, whereas actinomycin D did not impair platelet TF neosynthesis. The Mr of neosynthesized TF was unaffected by tunicamycin.

De novo synthesis of TF by platelets and PBMCs. Platelets or PBMCs with or without pretreatment with puromycin, actinomycin D, DRB, or tunicamycin were incubated with [35S]-methionine, and activated with TRAP or LPS. The platelet membranes before and after stimulation were immunoprecipitated with anti-TF antibodies and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, protein transfer, and autoradiography. (A) TF immunoprecipitated from platelet membranes with polyclonal α-TF Ab. Nonstimulated platelets reveal a dominant [35S]-TF band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 1). This pattern is almost identical to that of lane 3 (1-hour preincubation with 10 ng/mL tunicamycin). TRAP activation induces a new band (approximately 60 kDa), indicated by the asterisk, that is also unaffected by tunicamycin (lanes 2 and 4). When the incubation with tunicamycin was extended for 2 hours in nonactivated (lane 7) and activated (lane 8) platelets, the same results shown in lanes 3 and 4 were obtained. Puromycin abolishes all neosynthesis in TRAP-activated platelets (lane 6). In nonstimulated samples, puromycin induces a marked inhibition of the approximately 47-kDa TF, and abolishes all the remaining bands (lane 5). (B) the membrane TF of nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets was now immunoprecipitated with the α-TF MoAb. Lane 1 shows a modest incorporation of [35S]-methionine into TF in nonstimulated platelets, and the puromycin effect is shown in lane 2. Lane 3 shows the enhancement of the approximately 47-kDa TF neosynthesis after 30 minutes of TRAP activation, with a new approximately 60-kDa immunoreactive TF species. This band was abolished by puromycin, and the approximately 47-kDa band is considerably reduced (lane 4). (C) PBMC preparations were incubated with [35S]-methionine while activated with LPS for 5 hours. The flow cytometry of this sample showed that 17% and 10% of all events were CD14+ and CD61+, respectively. After cell lysis and centrifugation (18 000g for 15 minutes) the membrane (lanes 1-3) and supernatant (lanes 4-6) fractions were immunoprecipitated. With this prolonged stimulation, most of the radioactivity is recovered in the membrane fraction. The predominant bands in nonstimulated cells are of approximately 47 kDa and approximately 35 kDa, which were enhanced after LPS (lane 3) and suppressed by puromycin (lane 2). In the supernatant, the unstimulated PBMCs exhibit a predominant band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 4) which, upon stimulation, is slightly amplified with appearance of new bands, predominantly 1 of approximately 35 kDa (lane 5). All the bands are abolished by puromycin (lane 6).

De novo synthesis of TF by platelets and PBMCs. Platelets or PBMCs with or without pretreatment with puromycin, actinomycin D, DRB, or tunicamycin were incubated with [35S]-methionine, and activated with TRAP or LPS. The platelet membranes before and after stimulation were immunoprecipitated with anti-TF antibodies and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, protein transfer, and autoradiography. (A) TF immunoprecipitated from platelet membranes with polyclonal α-TF Ab. Nonstimulated platelets reveal a dominant [35S]-TF band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 1). This pattern is almost identical to that of lane 3 (1-hour preincubation with 10 ng/mL tunicamycin). TRAP activation induces a new band (approximately 60 kDa), indicated by the asterisk, that is also unaffected by tunicamycin (lanes 2 and 4). When the incubation with tunicamycin was extended for 2 hours in nonactivated (lane 7) and activated (lane 8) platelets, the same results shown in lanes 3 and 4 were obtained. Puromycin abolishes all neosynthesis in TRAP-activated platelets (lane 6). In nonstimulated samples, puromycin induces a marked inhibition of the approximately 47-kDa TF, and abolishes all the remaining bands (lane 5). (B) the membrane TF of nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets was now immunoprecipitated with the α-TF MoAb. Lane 1 shows a modest incorporation of [35S]-methionine into TF in nonstimulated platelets, and the puromycin effect is shown in lane 2. Lane 3 shows the enhancement of the approximately 47-kDa TF neosynthesis after 30 minutes of TRAP activation, with a new approximately 60-kDa immunoreactive TF species. This band was abolished by puromycin, and the approximately 47-kDa band is considerably reduced (lane 4). (C) PBMC preparations were incubated with [35S]-methionine while activated with LPS for 5 hours. The flow cytometry of this sample showed that 17% and 10% of all events were CD14+ and CD61+, respectively. After cell lysis and centrifugation (18 000g for 15 minutes) the membrane (lanes 1-3) and supernatant (lanes 4-6) fractions were immunoprecipitated. With this prolonged stimulation, most of the radioactivity is recovered in the membrane fraction. The predominant bands in nonstimulated cells are of approximately 47 kDa and approximately 35 kDa, which were enhanced after LPS (lane 3) and suppressed by puromycin (lane 2). In the supernatant, the unstimulated PBMCs exhibit a predominant band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 4) which, upon stimulation, is slightly amplified with appearance of new bands, predominantly 1 of approximately 35 kDa (lane 5). All the bands are abolished by puromycin (lane 6).

We never obtained platelet-free PBMC suspensions. In resting conditions, these preparations showed different degrees of TF synthesis, which increased substantially after LPS stimulation. Autoradiographs obtained 2 hours after LPS activation revealed that almost all the [35S]-TF was recovered in the supernatant fraction, not in the membranes, and that puromycin, but not actinomycin D or DRB, abolished TF neosynthesis (Figure S4). When the LPS stimulation was extended to 5 hours, the [35S]-TF was preferentially recovered in the membrane fraction, and was also completely inhibited by puromycin (Figure 4C). In this case, actinomycin D inhibited de novo TF synthesis observed in the supernatant fraction, but not that of PBMC membranes (not shown).

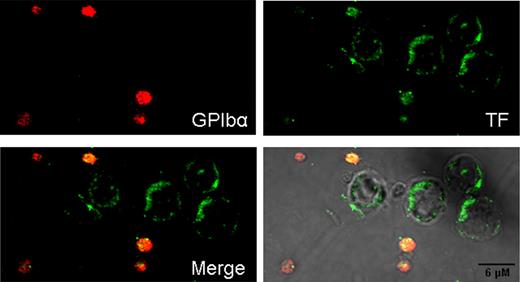

Immunofluorescence–confocal microscopy in resting and activated PBMC preparations

Immunofluorescence of resting PBMC preparations (Figure 5) illustrates the contamination with platelets. Leukocytes do not expose TF protein, whereas intense expression and TF colocalization with GPIbα are shown in the adjacent platelet. This was consistently observed in several experiments (Figure S5). When PBMC samples were stimulated for 5 hours with LPS, some leukocytes, presumably monocytes, expressed moderate amounts of TF protein in the cell periphery (Figure 6), consistent with the autoradiography findings.

Confocal immunofluorescence of TF and GPIbα in nonstimulated PBMC preparations. Unstimulated, fresh, nonpermeabilized suspensions of PBMCs were examined by contrast microscopy, Hoechst staining, and TF and GPIbα immunolabeling. No TF label is observed in leukocytes, whereas 1 platelet stained strongly for TF and GPIbα, with extensive colocalization of both glycoproteins. The other platelet is identified only by expression of the GPIbα label. Vis is phase contrast; arrows in Vis show platelets expressing GPIbα label.

Confocal immunofluorescence of TF and GPIbα in nonstimulated PBMC preparations. Unstimulated, fresh, nonpermeabilized suspensions of PBMCs were examined by contrast microscopy, Hoechst staining, and TF and GPIbα immunolabeling. No TF label is observed in leukocytes, whereas 1 platelet stained strongly for TF and GPIbα, with extensive colocalization of both glycoproteins. The other platelet is identified only by expression of the GPIbα label. Vis is phase contrast; arrows in Vis show platelets expressing GPIbα label.

Confocal immunofluorescence of TF protein expressed by LPS-stimulated PBMC preparations. PBMC suspensions, similar to those of Figure 5, were stimulated with LPS during 5 hours. Here, a distinctive TF label is observed in the cell periphery of leukocytes (presumably monocytes). Contaminating platelets stained strongly for GPIbα and TF, which showed extensive colocalization.

Confocal immunofluorescence of TF protein expressed by LPS-stimulated PBMC preparations. PBMC suspensions, similar to those of Figure 5, were stimulated with LPS during 5 hours. Here, a distinctive TF label is observed in the cell periphery of leukocytes (presumably monocytes). Contaminating platelets stained strongly for GPIbα and TF, which showed extensive colocalization.

Discussion

The origin, nature, and function of physiological bloodborne TF constitute a controversial issue. This study shows that human platelets contain TF mRNA, which is translated into de novo synthesized protein, mainly after activation. These processes are associated with increases of membrane-bound TF protein and platelet PCA.

TF mRNA detection in human platelets confirmed 2 recent reports.43,44 The platelet origin of TF mRNA was established after eliminating other TF-synthesizing cells (eg, monocytes). The purity of platelet suspensions was assessed by fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, and the absence of CD14 mRNA transcripts. In contrast, microscopy observation, flow cytometry, and amplification of platelet-specific GPIbα mRNA indicated platelet contamination of PBMC preparations. Thus, our platelet samples were essentially free of monocytes, whereas the PBMC preparations always had a variable number of platelets.

Expression of TF mRNA was observed in nonstimulated platelets of most individuals, but was induced in all of them after TRAP stimulation. This has been explained by the existence of pre-mRNA species that undergo an outside-in signaling to splice pre-mRNA into mature mRNA.42,44 Regarding PBMCs, most resting samples presented a narrow but discernible band of TF mRNA. The response of PBMCs to TRAP and LPS was different. TRAP activation for 15 minutes slightly increased the TF mRNA expression in 3 of 8 individuals, whereas in the remaining 5 patients, no effect was observed. In contrast, PBMCs stimulated with LPS for 2 hours showed a strong and consistent expression of TF mRNA, likely through a transcriptional process. Taken together, these observations suggest that TF mRNA in TRAP-stimulated PBMCs is platelet derived, possibly enhanced by platelet-monocyte interactions,17,24 whereas the 2-hour LPS stimulation induced the expression of genuine monocyte TF mRNA.

TF-mRNA expression in most of the “resting” platelet samples may be a consequence of ex vivo activation of platelets. Denis et al42 also found low levels of spliced IL-1β message in “quiescent” platelets, attributing it to activation during processing. Our platelet preparations exposed more surface P-selectin than platelets in whole blood, denoting some activation. Thus, platelet processing probably contributes to some extent to TF mRNA expression.44 However, in vivo activation-induced splicing cannot be excluded and an ongoing TF synthesis by circulating platelets could be postulated.

Fink et al,53 using laser-assisted microdissection and real-time PCR, found no TF mRNA in assays with up to 6 ×105 platelets, whereas Camera et al,43 also using real-time PCR, detected it in platelets starting with 100 ng of total RNA. Our preparations contained at least 108 platelets and approximately 1000 ng RNA, and the reverse transcriptase–PCR products were detected using silver-stained polyacrylamide gels.51 This probably explains the apparent discrepancy with Fink et al,53 who showed that the variability in relative amounts of specific mRNA was strictly dependent on the platelet mass and RNA amount. In fact, our study showed that platelet TF transcripts were less abundant than those of other proteins (ie, GPIbα). This is consistent with a report showing that TF mRNA is not in the list of the highly expressed platelet genes.54

Platelets isolated at RT or at 4°C attained a similar level of PCA after activation. However, nonstimulated platelets isolated at RT had always some basal PCA, whereas those processed at 4°C had no detectable PCA in our assay. These observations suggest that resting, circulating platelets have no physiologically significant PCA, and that some of this activity is elicited by ex vivo processing. The stimulation-induced PCA was substantially, though not completely, blocked by polyclonal α-TF or α-FVIIa MoAb, whereas antagonists of the intrinsic pathway (CTI, aPC, and anti-FVIIIC) had no inhibitory effect. Accordingly, FXa generation by stimulated platelets is predominantly TF-FVIIa dependent. Omission of FVIIa in the assay did not affect the PCA measurements. This apparently conflicting result confirms a similar finding,43 and may be explained by the recent demonstration that activated platelets expose FVIIa.55 Predictably, the immunorecognized TF protein measured by ELISA in nonstimulated platelets would be sufficient to express 2 or 3 times the PCA measured in stimulated platelets, assuming that platelet TF protein has the same relative activity than hrTF. Thus, circulating platelets would contain enough TF to account for the initiation of their clotting function. In this context, a preformed, rapidly exposed TF in active form,17,43 or more slowly decrypted56 upon stimulation, has been described. This probably would explain the lack of inhibitory effect of puromycin on platelet PCA (and Western blotting), either because neosynthesized TF is quantitatively insufficient, not yet fully processed, or not functionally exposed in the plasma membrane to be detectable by our assay.

The activation-induced PCA paralleled the TF protein increase in platelet membranes, as shown by biotin labeling and immunofluorescence–confocal microscopy. TF protein had been previously found in platelets using flow cytometry, Western blots, ELISA, immunoelectron microscopy, and immunocytochemistry.43,44,57,58 The approximately 47-kDa TF consistently found in most cell types was revealed with an α-TF MoAb in immunoprecipitates, both in nonstimulated and activated platelets. In addition, the polyclonal antibody used in Western blots disclosed other immunoreactive proteins appearing later after stimulation. Among these, the most consistently found had Mr of approximately 35 kDa and approximately 60 kDa. Tunicamycin did not affect TF Mr, denoting that N-glycosylation does not account for Mr differences of TF protein. The heterogeneity might be explained by partial degradation of TF, dimer,59 or heterodimer60 formation, or coprecipitation with other platelet proteins. In this regard, we have observed that TF coprecipitates with GPIbα-IX in resting platelets.61 It is remarkable that the postactivation increase of TF protein observed in Western blots (as well as in PCA) was not inhibited by puromycin. This observation, more difficult to understand, could be explained by lack of antibody reaction with a possibly protected TF, which would be increasingly exposed and recognized by the antibodies as the platelet activation progresses.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy observations confirmed the presence of TF in nonstimulated platelets and demonstrated its colocalization with the more abundant GPIbα, particularly after activation. Resting PBMCs showed no detectable TF, contrasting with the intense colocalized TF and GPIbα labels observed in adjacent platelets. However, prolonged activation with LPS elicited the appearance of TF in the periphery of some PBMCs, presumably monocytes in their way to becoming macrophages, without changing the TF exposure by platelets.

Lindmark et al,62 using flow cytometry in whole blood, found that platelet-monocyte complexes expressed TF antigen within 15 minutes after TRAP activation. In contrast, the highest response to LPS occurred 2 hours after stimulation. They concluded that the activated platelets induced the early TF expression by monocytes. Given that almost all of the blood monocytes were covered with platelets, it is difficult to establish in these experiments the origin of TF. In contrast, using a similar experimental design, a recent study63 concluded that TF expressed on leukocyte-platelet aggregates was probably of platelet origin. The different time-course responses to TRAP and LPS described by Lindmark et al62 are fully consistent with our results. We observed fast increases of TF mRNA, protein, and PCA in TRAP-activated platelets. In contrast, PBMCs showed a strong TF mRNA response after 2 hours of LPS stimulation. The LPS-induced TF mRNA expression in PBMCs was associated with some TF neosynthesis in this 2-hour period, which was completely abolished by puromycin, but not inhibited by actinomycin D or DRB. These observations suggest that TF neosynthesized by PBMCs in these conditions is platelet derived. The immunofluorescent confocal images provide further evidence that platelets only exposed to glass contact express TF, whereas the surrounding, fresh PBMCs have no visible label for the protein.

A crucial observation is that platelet activation induces or enhances the synthesis of TF; this was observed in all of the 25 experiments performed. Using 2 different α-TF antibodies, we observed that the Mr of [35S]-TF were similar to those found by immunoprecipitation or immunoblotting. The process was inhibited by puromycin, but not by actinomycin D or DRB, indicating that transcription was unneeded.40–42 The incorporation of [35S]-methionine into TF by nonstimulated platelets may reflect an ongoing synthesis in the circulation, or slight platelet activation ex vivo. We detected some interindividual variability, similar to that observed in interleukin-1β40 and PAI-141 synthesis: in some individuals, the incorporation of [35S]-methionine by nonactivated platelets was scanty. In others, the radioactivity was prominent in the approximately 35-kDa and approximately 60-kDa bands. In LPS-stimulated PBMCs, the TF synthesis was detected in the supernatant fraction 2 hours after stimulation, with negligible [35S]-TF incorporation into cell membranes. As discussed previously, this synthesis would be platelet derived: it is unaffected by transcription inhibitors and abolished by puromycin. The extended 5-hour stimulation induced a more intense TF synthesis, and the new protein with an Mr of approximately 60 kDa was mainly recovered in membrane fractions. Again, the synthesis of this TF protein was unaffected by actinomycin D, supporting a platelet origin. However, the approximately 30-kDa [35S]-TF species found in the supernatant fraction of activated PBMCs was inhibited by actinomycin D (not shown), probably denoting the start of genuine monocyte synthesis of TF not yet fully processed and not incorporated into membranes.

In summary, we found that activated platelets synthesize TF. Shortly after activation, however, the newly synthesized protein does not contribute detectably to increase the TF-dependent PCA; in fact, puromycin abolishes the TF synthesis without inhibiting the platelet PCA. This implies that the clotting activity of platelets shortly after activation would be supported by preformed TF. In all our experiments in nonstimulated platelets, we found TF protein and de novo synthesis of TF, as well as TF mRNA in platelets of most individuals. Some of these findings may respond to ex vivo slight platelet activation. However, and although direct proof is still needed, the weight of our data suggest that circulating platelets contain preformed TF, readily functional to participate in hemostatic or thrombotic processes, that do not require additional sources of TF to express PCA. Whether this postulated ongoing de novo TF synthesis during the platelet lifespan occurs through a physiologically modulated process or in response to mild, reversible encounters in the circulation remains to be elucidated. In this regard, it was recently shown that circulating platelets in sepsis have spliced TF mRNA, supporting in vivo TF synthesis.64

Our results, as a whole, complement recent findings43,44 and in several aspects agree with the points of view of Engelmann57 and Lösche.58 The current paradigm of the physiologic cell-based clotting system assigns the platelets a pivotal role in assembling the coagulation complexes on their membranes while demanding an additional source of TF to trigger the reactions.45 Human platelets, as novel TF-synthesizing cells, would play the role of these “TF-bearing cells,” ensuring the localization of TF in the right place and at the right time. This prompt exposure, precise spatial location, and progressive and orderly layering of active TF on the platelet membrane configure a more rational model to explain hemostatic mechanisms in health and disease. In fact, the modulated progress of thrombin generation and fibrin deposition on the surface of platelets, like mortar laid on bricks, would build up either physiologic hemostatic plugs or thrombi. This concept highlights the incomparable role of platelets for unifying the primary and secondary hemostasis, modulating the times of both processes and emphasizing the self-sufficiency of intravascular components to accomplish all hemostatic needs. This formulation does not seek for foreign sources of TF, like microparticles and leukocytes, but also does not dismiss their potential contribution in specific conditions. It also solves the problem of the restricted accessibility of clotting factors to the vascular wall TF.21 Probably, the decreased thrombin generation evoked by aspirin65 and anti-GPIIb/IIIa drugs66 is also related to a reduced exposure of active TF on platelets. Finally, variability in platelet TF expression, synthesis, and activity among individuals must be further characterized to determine its potential predictive value for both thrombotic and bleeding events.

Several results of this manuscript were presented in abstract form in the XXth Congress of the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Sydney, Australia, August 11, 2005.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of the issue.

The online version of this manuscript contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mauricio Ocqueteau and Patricia Hidalgo (Department of Hematology-Oncology, School of Medicine, P. Catholic University of Chile) for their counseling and help in the flow cytometry studies and to Juan A. Godoy, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Centro de Regulación Celular y Patología, for his help in the confocal microscopy studies.

This work is supported by grant nos. 8010002 (D.M., J.P., T.Q.) and 1060637 (D.M.) from Fondecyt, Chile.

Authorship

Contribution: O.P., V.M, C.G.S. and D.M. participated in designing the research; O.P., V.M. and C.G.S performed the experiments and collected the data; O.P., V.M., C.G.S. and D.M. analyzed the data; J.P., and T.Q. contributed with ideas and suggestions for new experiments, with their expertise with some analytical tools and participated actively in the discussion of results and in the reviewing of the manuscript; D.M. wrote the paper; and all the authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Diego Mezzano, Department of Hematology-Oncology, School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, PO Box 114-D, Santiago, Chile; e-mail: dmezzano@med.puc.cl.

![Figure 4. De novo synthesis of TF by platelets and PBMCs. Platelets or PBMCs with or without pretreatment with puromycin, actinomycin D, DRB, or tunicamycin were incubated with [35S]-methionine, and activated with TRAP or LPS. The platelet membranes before and after stimulation were immunoprecipitated with anti-TF antibodies and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, protein transfer, and autoradiography. (A) TF immunoprecipitated from platelet membranes with polyclonal α-TF Ab. Nonstimulated platelets reveal a dominant [35S]-TF band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 1). This pattern is almost identical to that of lane 3 (1-hour preincubation with 10 ng/mL tunicamycin). TRAP activation induces a new band (approximately 60 kDa), indicated by the asterisk, that is also unaffected by tunicamycin (lanes 2 and 4). When the incubation with tunicamycin was extended for 2 hours in nonactivated (lane 7) and activated (lane 8) platelets, the same results shown in lanes 3 and 4 were obtained. Puromycin abolishes all neosynthesis in TRAP-activated platelets (lane 6). In nonstimulated samples, puromycin induces a marked inhibition of the approximately 47-kDa TF, and abolishes all the remaining bands (lane 5). (B) the membrane TF of nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets was now immunoprecipitated with the α-TF MoAb. Lane 1 shows a modest incorporation of [35S]-methionine into TF in nonstimulated platelets, and the puromycin effect is shown in lane 2. Lane 3 shows the enhancement of the approximately 47-kDa TF neosynthesis after 30 minutes of TRAP activation, with a new approximately 60-kDa immunoreactive TF species. This band was abolished by puromycin, and the approximately 47-kDa band is considerably reduced (lane 4). (C) PBMC preparations were incubated with [35S]-methionine while activated with LPS for 5 hours. The flow cytometry of this sample showed that 17% and 10% of all events were CD14+ and CD61+, respectively. After cell lysis and centrifugation (18 000g for 15 minutes) the membrane (lanes 1-3) and supernatant (lanes 4-6) fractions were immunoprecipitated. With this prolonged stimulation, most of the radioactivity is recovered in the membrane fraction. The predominant bands in nonstimulated cells are of approximately 47 kDa and approximately 35 kDa, which were enhanced after LPS (lane 3) and suppressed by puromycin (lane 2). In the supernatant, the unstimulated PBMCs exhibit a predominant band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 4) which, upon stimulation, is slightly amplified with appearance of new bands, predominantly 1 of approximately 35 kDa (lane 5). All the bands are abolished by puromycin (lane 6).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/12/10.1182_blood-2006-06-030619/4/m_zh80120702040004.jpeg?Expires=1765036352&Signature=Go6cd~pbqi4uCH~nJpsVZDaOC5ER5Iyl3btiWqa~S-G48WR4PI~4z7eer-KEntrgII33Vt4w90ZMPr9h3DICWlYQ2sXPqY9QWTFe0sgJjMgeg7hIUydPtu7dE14agJ6YWNfyzuYF7UFuFYTkeVVZQIvL-qRLlUfEWLFkh07gRaZT4OZwPEeTa7eJlpF5-uI2CdiEgvF51JM47RDl-vAwv~9d3uBXn~YTsD1OpUFyngJkHp7z8s3GjzghRrNz6FX85iWgtlZIWbmmdsJ27B1V-QEtaLbjXac6Z6dgB7Q3OlpF8cTnzwyOCV5~kfeUEx5p5lT-6mParKVHsrZuue9g4A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. De novo synthesis of TF by platelets and PBMCs. Platelets or PBMCs with or without pretreatment with puromycin, actinomycin D, DRB, or tunicamycin were incubated with [35S]-methionine, and activated with TRAP or LPS. The platelet membranes before and after stimulation were immunoprecipitated with anti-TF antibodies and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, protein transfer, and autoradiography. (A) TF immunoprecipitated from platelet membranes with polyclonal α-TF Ab. Nonstimulated platelets reveal a dominant [35S]-TF band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 1). This pattern is almost identical to that of lane 3 (1-hour preincubation with 10 ng/mL tunicamycin). TRAP activation induces a new band (approximately 60 kDa), indicated by the asterisk, that is also unaffected by tunicamycin (lanes 2 and 4). When the incubation with tunicamycin was extended for 2 hours in nonactivated (lane 7) and activated (lane 8) platelets, the same results shown in lanes 3 and 4 were obtained. Puromycin abolishes all neosynthesis in TRAP-activated platelets (lane 6). In nonstimulated samples, puromycin induces a marked inhibition of the approximately 47-kDa TF, and abolishes all the remaining bands (lane 5). (B) the membrane TF of nonstimulated and TRAP-activated platelets was now immunoprecipitated with the α-TF MoAb. Lane 1 shows a modest incorporation of [35S]-methionine into TF in nonstimulated platelets, and the puromycin effect is shown in lane 2. Lane 3 shows the enhancement of the approximately 47-kDa TF neosynthesis after 30 minutes of TRAP activation, with a new approximately 60-kDa immunoreactive TF species. This band was abolished by puromycin, and the approximately 47-kDa band is considerably reduced (lane 4). (C) PBMC preparations were incubated with [35S]-methionine while activated with LPS for 5 hours. The flow cytometry of this sample showed that 17% and 10% of all events were CD14+ and CD61+, respectively. After cell lysis and centrifugation (18 000g for 15 minutes) the membrane (lanes 1-3) and supernatant (lanes 4-6) fractions were immunoprecipitated. With this prolonged stimulation, most of the radioactivity is recovered in the membrane fraction. The predominant bands in nonstimulated cells are of approximately 47 kDa and approximately 35 kDa, which were enhanced after LPS (lane 3) and suppressed by puromycin (lane 2). In the supernatant, the unstimulated PBMCs exhibit a predominant band of approximately 47 kDa (lane 4) which, upon stimulation, is slightly amplified with appearance of new bands, predominantly 1 of approximately 35 kDa (lane 5). All the bands are abolished by puromycin (lane 6).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/12/10.1182_blood-2006-06-030619/4/m_zh80120702040004.jpeg?Expires=1765217437&Signature=PiJwdAHP2Sf6WJPK5zg-u1C8FVWsl6PtuFAsazgolJ5eU8y6reQ2ybyCsDkBgZWocEFKj2my7s0mWztTQrUxzYND0avE0vFW7XuacxNsL2RA66zVNYYNgBCxudoG-8PExAMpztvLcgXTvcEDGZEb5JD3Poaf-9oejXODEPJW05nCAXx8jeaeItjc8meD1alaz-cNBtM9xjDjzfn3~w0SsLNlciv1bZ-Aok7EXZi1W5LJTYJfnPmXUMtIo4HFea7KGTcxViUmrd5UAsyTNicqGlvHW~9pcz6OTft4plgwG61K-cZZo0xUXvpH~imzzxmN4CshrxlBB7wtbZ~iP72stg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)