Abstract

Interaction between von Willebrand factor (VWF) and platelet GP Ib-IX-V is required for hemostasis, in part because intracellular signals from VWF/GP Ib-IX-V activate the ligand-binding function of integrin αIIbβ3. Because they also induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the ADAP adapter, we investigated ADAP's role in GP Ib-IX-V signal transduction. Fibrinogen or ligand-mimetic POW-2 Fab binding to αIIbβ3 was stimulated by adhesion of ADAP+/+ murine platelets to dimeric VWF A1A2 but was significantly reduced in ADAP−/− platelets (P < .01). αIIbβ3 activation by ADP or a Par4 thrombin receptor agonist was also decreased in ADAP−/− platelets. ADAP stabilized the expression of another adapter, SKAP-HOM, via interaction with the latter's SH3 domain. However, no abnormalities in αIIbβ3 activation were observed in SKAP-HOM−/− platelets, which express normal ADAP levels, further implicating ADAP as a modulator of αIIbβ3 function. Under shear flow conditions over a combined surface of VWF A1A2 and fibronectin to test interactions involving GP Ib-IX-V and αIIbβ3, respectively, ADAP−/− platelets displayed reduced αIIbβ3-dependent stable adhesion. Furthermore, ADAP−/− mice demonstrated increased rebleeding from tail wounds. These studies establish ADAP as a component of inside-out signaling pathways that couple GP Ib-IX-V and other platelet agonist receptors to αIIbβ3 activation.

Introduction

Binding of von Willebrand factor (VWF) to GP Ib-IX-V is important for the initial capture of platelets to the extracellular matrix of injured blood vessels at high shear rates.1-3 GP Ib-IX-V is a complex of 4 transmembrane polypeptides.4-6 While the cytoplasmic tail of each subunit lacks catalytic function, each may interact directly or indirectly with proteins that can transmit intracellular signals. For example, the cytoplasmic tail of GP Ibα can interact directly with filamin; GP Ibα and Ibβ tails can interact with 14-3-3-ζ; and GP Ibβ and GP V tails can interact with calmodulin.7-10 GP Ib-IX-V can be coimmunoprecipitated from platelets with signaling molecules, including Src family kinases,11 phosphatidyl inositol (PI) 3-kinase,12 and SHIP-2.13 Furthermore, VWF-dependent platelet activation may require localization of GP Ib-IX-V to lipid rafts, membrane structures implicated in cellular signaling.14 In a recent study, we demonstrated that the interaction of GP Ib-IX-V with the dimeric A1 domain of VWF is sufficient to trigger a sequence of reactions in platelets that leads to activation of αIIbβ3 (inside-out signaling), even when costimulatory inputs from other agonist receptors are blocked.15 These reactions include activation of Src family kinases, intracellular Ca2+ oscillations, and the actions of PI 3-kinase and protein kinase C. An unanticipated finding was the tyrosine phosphorylation of ADAP, a Src substrate not previously recognized as a potential effector in GP Ib-IX-V signaling.

ADAP (adhesion and degranulation promoting adapter protein; previously called Fyb or SLAP-130) is a variably spliced 120 or 130 kDa protein expressed in T cells and other hematopoietic cells.16-18 Notable domains or motifs in ADAP include 2 potential nuclear localization sequences16 ; polyproline-rich regions in the amino terminal half of the molecule that can interact with the SH3 domains of SKAP5519 and SKAP-HOM20,21 ; and several tyrosines, including Y595 and Y651, which when phosphorylated enable binding to the SH2 domains of SLP-76 or Fyn in T cells.17,18,22 ADAP can potentially modulate cytoskeletal interactions through an FP4 motif that recognizes the EVH1 domain of VASP23 and a polyproline-rich region that recognizes the SH3 domain of mammalian actin binding protein 1 (mAbp1).24 Furthermore, ADAP can coimmunoprecipitate with WASP and Arp 2/3, known regulators of actin polymerization.23,25 Thus, ADAP is a candidate linker between cell activation events at the plasma membrane and intracellular events that effect changes in actin polymerization, dynamics, and organization.

Studies in ADAP knockout mice or ADAP-deficient T cells have indicated a necessary role for ADAP in the regulation of T-cell proliferation and IL-2 production26 and the promotion of cell adhesion through clustering and valency modulation of β1 and β2 integrins.27-32 However, no information exists as to whether ADAP is necessary for integrin affinity modulation in general or for αIIbβ3 function in platelets. Given the aforementioned tyrosine phosphorylation of ADAP in response to engagement of GP Ib-IX-V,15 we investigated here whether this adapter is required for GP Ib-IX-V–triggered activation of αIIbβ3. The results using ADAP−/− mice establish that ADAP is involved in receptor-mediated affinity modulation of αIIbβ3, with consequences for platelet adhesive function ex vivo and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Preparation of dimeric, murine A1A2 VWF (dmA1A2 VWF) was similar to that of human dA1 VWF33 except that it encompassed residues 445 to 909 of murine VWF. POW-2, an antibody Fab fragment to murine activated αIIbβ3, has been described.34-36 Monoclonal antibody 1B5 against murine αIIbβ3 was from Dr Barry Coller (Rockefeller University, New York, NY)37 ; polyclonal antibodies developed against the amino-terminus of murine ADAP and SKAP-HOM have been described17,20,38,39 ; monoclonal antibodies against murine CD62P (P selectin) and anti-CD41(αIIb) were from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); and a monoclonal antibody against murine GP Ibα was from Emfret Analytics (Eibelstadt, Germany). Fibronectin was from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) and fibrinogen from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). QiaAMP DNA Mini Kit, plasmid vectors pcDNA 3.1 and pIRESeEGFP, and Lipofectamine were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Convulxin was from Alexis Biochemicals (Lausen, Switzerland). PPACK was from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). SuperSignal WestPico reagent was from Pierce Chemicals (Rockford, IL). All other reagents were from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO).

Mouse strains and bleeding times

ADAP−/− and SKAP-HOM−/− mice have been described.28,40 ADAP+/+ and SKAP-HOM+/+ mice represent littermate controls. Bleeding time assays were performed by placing the tails of mice in a Plexiglas restraining device, prewarming the tails to 37°C in normal saline, and cutting transversely 0.5 cm from the tip. After immediate reimmersion in the saline solution, the time to arrest of bleeding was noted. Tail bleeding was further monitored for at least an additional 60 seconds to determine if rebleeding occurred. Statistical analyses for bleeding times and rebleeding times were performed using the Student t test and the χ2 test, respectively.

Platelet preparation

Mouse blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and diluted with an equal volume of modified Tyrode buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM NaH2PO4.H2O, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM dextrose, pH 6.5) containing acid-citrate dextrose anticoagulant and 1.5 U/mL apyrase. After centrifugation for 4 minutes at 450g, the platelet-rich plasma was removed, centrifuged for 15 minutes at 800g in the presence of 0.5 U/mL apyrase and 1 μM PGE1, and platelet pellets were resuspended in Walsh buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2.6H2O, 3.3 mM NaH2PO4.H2O, 3.8 mM HEPES, 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 0.1% dextrose, pH 7.35).41

Characterization of ADAP−/− platelets

To determine the surface expression of αIIbβ3 and GP Ibα, platelets were incubated with an antibody against murine anti-CD41 (αIIb) or against murine GP Ibα in Tyrode buffer (137 mM NaCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 26 mM KCl, 5.5 mM glucose, 0.1% BSA, 5.0 mM Hepes, 0.5 mM CaCl2,1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) for 30 minutes. Platelet suspensions were diluted with buffer, and the amount of antibody bound to platelets was determined by flow cytometry. CD62P (P selectin) surface expression, reporting on α-granule secretion, was determined by flow cytometric analysis of binding of an antibody against murine CD62P in platelets that were resting or stimulated with 250 μM Par4 receptor-activating peptide (AYPGKF). Statistical analyses were performed using the Student t test.

Measurements of αIIbβ3 affinity state

Binding of FITC-fibrinogen or POW-2 Fab41 to mouse platelets adherent to dmA1A2 VWF was evaluated by deconvolution microscopy. Glass coverslips were coated with 15 μg/mL dmA1A2 VWF for 1 hour at room temperature and blocked with 1% denatured BSA. Platelets were added to the coverslips for 40 minutes at 37°C, routinely in the presence of FITC-fibrinogen or POW-2 Fab, 2 U/mL apyrase, 10 μM indomethacin, and a phycoerythrin-conjugated, noninhibitory antibody to β3, the latter to facilitate discrimination of the cell outline. Nonspecific fibrinogen or POW-2 Fab binding was assessed in the presence of 5 mM EDTA. Adherent platelets were washed gently with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, and stained with Alexa-488–conjugated anti–murine H + L chain–specific IgG (for POW-2 Fab). Images were captured with a Deltavision deconvolution microscope (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) using a Photometrics (Tucson, AZ) Sony Coolsnap HQ charged-coupled device camera system (Sony, Park Ridge, NJ) attached to an inverted, wide-field fluorescence microscope (Nikon [Melville, NY] TE-200) equipped with a 100× Nikon (NA 1.4) oil-immersion objective. Identical settings were used for slides from all experimental conditions. Platelet fluorescence intensity range was standardized in deconvolution micrographs using the Softworks Analysis Program (Applied Precision). Single-cell analysis was performed by calculating fluorescence intensities for FITC-fibrinogen bound to each cell using Image-Pro Plus Software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). The mean for each group was determined from data derived from 50 to 300 cells per experimental condition for both ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets. Results are expressed as the percentage of average ADAP+/+ fluorescence ± standard error of the mean (SEM). To determine the role of ADAP in αIIbβ3 activation through agonists other than GP Ib-IX-V, platelets from ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− mice were stimulated with varying concentrations of ADP, Par4-activating peptide,42 or convulxin in the presence of FITC-fibrinogen, and bound FITC-fibrinogen was assessed by flow cytometry at equilibrium binding conditions. Platelet aggregation was measured as previously described.43 Statistical analyses were performed using the Student t test.

Platelet adhesion under flow conditions

Whole blood was drawn from the retro-orbital plexus and anticoagulated with 40 μg/mL PPACK. Platelet number was adjusted in blood from ADAP+/+ mice to correspond to the reduced counts in ADAP−/− mice by centrifuging for 8 minutes at 750g and carefully depleting platelets from the buffy coat, thus maintaining hematocrit. Remaining cells and plasma were reblended very gently. Glass coverslips were coated with either 20 μg/mL dmA1A2 VWF, 25 μg/mL fibronectin, or a combination of the two for 45 minutes at room temperature, rinsed with buffer containing 20 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, and mounted in a parallel plate flow chamber maintained at 37°C. Platelet dense granules were labeled by addition of 20 μg/mL mepacrine to whole blood to allow platelet visualization with an inverted epifluorescence microscope.1 Blood was aspirated through the chamber at a shear rate of 1500 s−1. No platelets were in contact with the surface prior to initiation of shear flow. Analog videotaped images of platelets directly captured to the surface from shear flow were subsequently digitized using Adobe Premiere (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). The number of platelets that remain stationary (displaced by less than 1 cell diameter) for the specified time period was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the total number of platelets contacting the surface over the period of observation. Data are shown for platelets adherent at 20 seconds, 1 minute, or 2 minutes following initiation of flow. From 800 to 1500 platelets were analyzed for each data point shown. Following flow, platelets were fixed in situ by flowing 3.7% formaldehyde, rinsed, permeabilized, and stained with a noninhibitory, FITC-conjugated antibody against αIIb.

Studies of ADAP and SKAP-HOM in a CHO cell model system

A5 CHO cells that stably express αIIbβ3 were a gift from Dr M. Ginsberg (University of California San Diego) and cultured as described.44 The following mammalian expression plasmids were used: pEF-BOS/Flag-tagged SKAP-HOM20 and pEF/Flag-tagged ADAP.17 The SKAP-HOM plasmid was used as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) template to obtain full-length SKAP-HOM and SKAP-HOM lacking the amino terminal SH3 domain, and PCR products were subcloned into pIRES2-EGFP (Invitrogen) at 5′ XhoI and 3′ SacI restriction sites. Coding sequences were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing. For transfection, subconfluent cells in 100 mm plates were transfected with a maximum of 6 μg plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). When required, pcDNA 3.1 (Invitrogen) was used to maintain equal quantities of cDNA per transfection. Cells were examined for ADAP and SKAP-HOM expression 48 hours after transfection, a time point verified to produce maximal recombinant protein levels.

Results and discussion

ADAP-deficient mice rebleed from tail wounds

To address the role of ADAP in platelet function, we studied mice deficient in this protein. Tail bleeding times in the mouse can be prolonged if there are coagulation abnormalities or platelet dysfunction, but not mild thrombocytopenia,45 although subtle defects in platelet function may yield only an increase in tail rebleeding frequency due to thrombus fragility.43 ADAP−/− mice exhibited bleeding times comparable to their ADAP+/+ littermates (Figure 1A), confirming that the mild thrombocytopenia in these mice28 was not itself sufficient to prolong bleeding. However, whereas only 21.9% of ADAP+/+ mice showed rebleeding from tail wounds within 1 minute of initial arrest, 61.8% of ADAP−/− mice rebled (P < .01 in a χ2 test) (Figure 1B). Plasma from ADAP−/− mice showed normal thrombin and activated partial thromoboplastin times (not shown), suggesting that the higher rebleeding rate in ADAP−/− mice was likely due to platelet dysfunction.

Bleeding times in wild-type or ADAP knockout mice. Tails of ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice were warmed and then transected 0.5 mm from the end and immersed in 0.9% isotonic saline solution at 37°C. Blood flow was monitored, and the time when bleeding arrested initially was noted as the bleeding time. Tails were monitored further for a minimum of 60 seconds to determine if bleeding recurred. (A) Bleeding times ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Percentage of mice that showed rebleeding. Results are calculated from measurements on a total of 33 ADAP+/+ and 37 ADAP−/− mice.

Bleeding times in wild-type or ADAP knockout mice. Tails of ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice were warmed and then transected 0.5 mm from the end and immersed in 0.9% isotonic saline solution at 37°C. Blood flow was monitored, and the time when bleeding arrested initially was noted as the bleeding time. Tails were monitored further for a minimum of 60 seconds to determine if bleeding recurred. (A) Bleeding times ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Percentage of mice that showed rebleeding. Results are calculated from measurements on a total of 33 ADAP+/+ and 37 ADAP−/− mice.

Characterization of ADAP−/− platelets

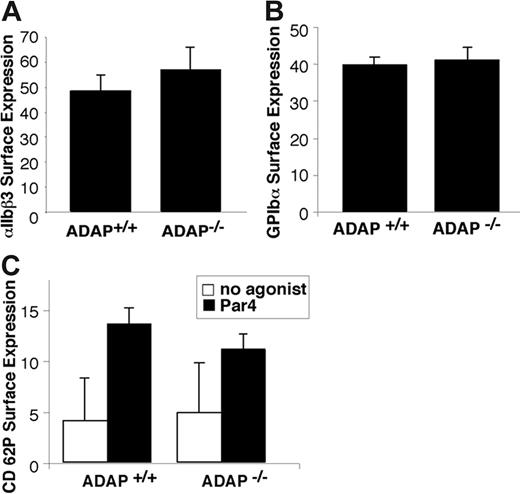

Expression of GP Ib-IX-V and αIIbβ3 was comparable in ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets as assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 2A-B). The botrocetin-mediated binding of FITC-VWF was also comparable, indicating that GP Ib-IX-V can interact normally with VWF (not shown). ADAP−/− platelets also exhibited normal α-granule secretion in response to Par4-activating peptide, as measured by surface expression of P selectin. Thus, to the extent that α-granule secretion may contribute to thrombus growth or stability, a defect in this process is not likely to be the primary cause of the increased frequency of tail rebleeding observed in the ADAP−/− mice.

Characterization of ADAP−/− platelets. Washed platelets from ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− mice were incubated with the appropriate antibodies, and binding was determined by flow cytometry. (A) αIIbβ3 surface expression. (B) GP Ibα surface expression. (C) α-granule secretion. Platelets were resting, or activated with 250 μM Par4-activating peptide, and the binding of an anti–murine P selectin antibody was determined. There was no statistically significant difference in P selectin expression between ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets in response to Par4-activating peptide despite statistically significant increases in P selectin expression compared with resting platelets. Results shown represent a summary of at least 4 experiments and show the average ligand binding ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Characterization of ADAP−/− platelets. Washed platelets from ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− mice were incubated with the appropriate antibodies, and binding was determined by flow cytometry. (A) αIIbβ3 surface expression. (B) GP Ibα surface expression. (C) α-granule secretion. Platelets were resting, or activated with 250 μM Par4-activating peptide, and the binding of an anti–murine P selectin antibody was determined. There was no statistically significant difference in P selectin expression between ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets in response to Par4-activating peptide despite statistically significant increases in P selectin expression compared with resting platelets. Results shown represent a summary of at least 4 experiments and show the average ligand binding ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

ADAP is required for normal αIIbβ3 activation

Primary hemostasis is reliant on initial capture of platelets to the vessel wall, platelet activation, and recruitment of additional platelets into growing thrombi. GP Ib-IX-V is important from this standpoint, and Bernard-Soulier patients and mice deficient in GP Ibα exhibit severe bleeding defects.46 GP Ib-IX-V is the only known receptor that can successfully mediate platelet capture across a wide range of physiologically relevant shear stresses.47,48 Furthermore, its signaling functions are important for αIIbβ3 activation and for the resulting stable platelet adhesion and aggregation. To investigate the contribution of ADAP to GP Ib-IX-V–induced αIIbβ3 activation, platelets from ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice were allowed to adhere to a GP Ib-IX-V–specific ligand, dmA1A2 VWF, in the presence of soluble FITC-fibrinogen, a ligand for activated αIIbβ3.

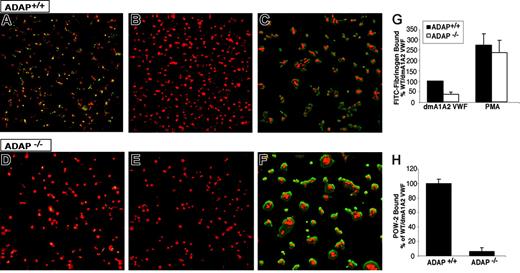

Apyrase and indomethacin were present to prevent costimulatory effects of ADP and thromboxane A2, respectively.15 Adhesion of wild-type ADAP+/+ platelets to dmA1A2 VWF induced the binding of FITC-fibrinogen, as evidenced by patches of green fluorescence associated with the platelets (Figure 3A). Fibrinogen binding was αIIbβ3 specific because it was prevented by EDTA (Figure 3B) and by 1B5, a function-blocking antibody to αIIbβ3 (data not shown). In contrast, there was much less specific FITC-fibrinogen binding to ADAP−/− platelets under the same conditions (Figure 3D-E). A quantitative analysis indicated a statistically significant 64% ± 10% decrease in FITC-fibrinogen binding to ADAP−/− platelets compared with ADAP+/+ platelets (P < .01) (Figure 3G). Addition of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), which circumvents platelet agonist receptors by directly stimulating intracellular mediators, such as protein kinase C49 and CalDAG-GEFI,50 caused increased FITC-fibrinogen binding to both ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets adherent to dmA1A2 VWF. This indicates that αIIbβ3 is inherently functional in ADAP−/− mouse platelets. PMA also induced increased platelet spreading (Figure 3C,F). To confirm that adhesion to dmA1A2 VWF stimulated an increase in αIIbβ3 affinity, the binding of POW-2, a ligand-mimetic, monovalent anti-αIIbβ3 antibody Fab, was assessed. Compared with ADAP+/+ platelets, there was a 94% ± 5% decrease in POW-2 binding to ADAP−/− platelets (Figure 3H; P < .01). Taken together, these results indicate that ADAP is involved in the modulation of αIIbβ3 affinity in response to ligation of GP Ib-IX-V by dmA1A2 VWF.

Integrin activation induced by GP Ib-IX-V. Washed platelets from ADAP+/+ (A-C) or ADAP−/− (D-F) mice were allowed to settle on dmA1A2 VWF. The activation state of αIIbβ3 was reported by the binding of soluble FITC-fibrinogen (green). A noninhibitory antibody to αIIbβ3 was used to view the cell outline (red). (A and D) Platelets were on dmA1A2 VWF in the presence of a cocktail of inhibitors against ADP and thromboxane A2. (B and E) As in panels A and D, with the addition of EDTA. (C and F) Platelets were on dmA1A2 VWF and activated with PMA without inhibitors. Results shown are representative of at least 3 experiments with similar results. (G-H) Quantification of specific, activation-dependent FITC-fibrinogen (G) or POW-2 Fab (H) binding to αIIbβ3 in response to GP Ib-IX-V ligation, as shown in panels A to F for FITC-fibrinogen. Results for ADAP−/− (white bars) are depicted as a percentage of the soluble ligand that is specifically bound by ADAP+/+ platelets (black bars) ± SEM. Data represent a summary of 4 experiments.

Integrin activation induced by GP Ib-IX-V. Washed platelets from ADAP+/+ (A-C) or ADAP−/− (D-F) mice were allowed to settle on dmA1A2 VWF. The activation state of αIIbβ3 was reported by the binding of soluble FITC-fibrinogen (green). A noninhibitory antibody to αIIbβ3 was used to view the cell outline (red). (A and D) Platelets were on dmA1A2 VWF in the presence of a cocktail of inhibitors against ADP and thromboxane A2. (B and E) As in panels A and D, with the addition of EDTA. (C and F) Platelets were on dmA1A2 VWF and activated with PMA without inhibitors. Results shown are representative of at least 3 experiments with similar results. (G-H) Quantification of specific, activation-dependent FITC-fibrinogen (G) or POW-2 Fab (H) binding to αIIbβ3 in response to GP Ib-IX-V ligation, as shown in panels A to F for FITC-fibrinogen. Results for ADAP−/− (white bars) are depicted as a percentage of the soluble ligand that is specifically bound by ADAP+/+ platelets (black bars) ± SEM. Data represent a summary of 4 experiments.

Because GP Ib-IX-V is important for mediating initial platelet surface interactions under shear flow, we tested whether ADAP was required for activation of αIIbβ3 and stable adhesion in platelets captured from shear flow through GP Ib-IX-V. In preliminary experiments, we verified that adhesion and translocation on dmA1A2 VWF were normal in ADAP−/− platelets, and therefore any differences observed in stable adhesion would not be attributable to defective VWF/GP Ib-IX-V interactions. Blood was perfused at a wall shear rate of G = 1500 s−1 over a surface of either dmA1A2 VWF, fibronectin, or a combination of the two. Unlike for adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen,1 αIIbβ3 must be in a high-affinity state to stably adhere to fibronectin in shear flow.51 Thus, with a mixed dmA1A2 VWF/fibronectin surface, we expected that initial platelet contacts through the GP Ib-IX-V/VWF A1 domain interaction would be reinforced by contacts through the αIIbβ3/fibronectin interaction only if αIIbβ3 had become activated. Indeed, this was the case for ADAP+/+ platelets, which displayed an increase in the average time that they remained stably adherent to the combined dmA1A2 VWF/fibronectin surface when compared with the single dmA1A2 VWF surface (Figure 4) (P < .05). The function-blocking anti-αIIbβ3 antibody 1B5 reduced stable adhesion to the combined surface to levels observed with dmA1A2 VWF alone (not shown) (P < .05), confirming that this response was αIIbβ3 dependent. Almost no platelet adhesion to a surface of fibronectin alone or soluble thrombi was observed at this shear rate, indicating that platelets that were stably adherent had not simply become preactivated during preparative procedures. In contrast to ADAP+/+ platelets, stable adhesion of ADAP−/− platelets to the combined surface was impaired (Figure 4). While on the dmA1A2 VWF surface, ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets showed similar levels of adhesion, on the combined surface with the αIIbβ3 ligand, fibronectin, ADAP−/− platelets were less able to adhere stably. Whereas there was a 27% to 43% decrease in the percentage of ADAP−/− platelets stably adherent for at least 3.5 seconds (Figure 4A), the decrease in the percentage of platelets stably adherent for at least 10 seconds was 50% to 85% (P < .05) at the time points after initiation of flow shown (Figure 4B). It is possible that multimeric VWF may have provided a better substrate than a combined matrix of dmA1A2 VWF and fibronectin, because GP Ib-IX-V and αIIbβ3 binding sites are optimally present within the same molecule. However, VWF was not used as a surface because murine GP Ibα does not recognize human VWF directly, and murine VWF was not available. Nevertheless, under conditions of shear flow we were able to distinguish small but significant increases in stable adhesion when the fibronectin αIIbβ3 ligand was presented on the surface along with dmA1A2 VWF. Thus, the results are consistent with a role for ADAP in inside-out signaling and activation of αIIbβ3 initiated by platelet adhesion through GP Ib-IX-V. The differences observed in stable adhesion between ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets may also be due in part to differences in response to generated secondary agonists, stabilization of ligand-receptor contacts, and cytoskeletal reinforcements.52-55

GP Ib-IX-V–induced αIIbβ3 activation under shear flow. Whole blood from ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice was adjusted to correct for thrombocytopenia of ADAP−/− mouse blood and aspirated over a coverslip coated with dmA1A2 VWF, with or without fibronectin (FN), and placed in a parallel plate flow chamber. The total number of platelets tethering to the surface was measured, and the percentage of these platelets that remained stationary for 3.5 seconds or 10 seconds was determined at 20 seconds, 1 minute, or 2 minutes after the initiation of flow. Results represent stationary platelets, as a percentage of the total number of platelets contacting the surface within the sampling time, ± SEM. (A) Platelets stationary for 3.5 seconds. (B) Platelets stationary for 10 seconds. Stationary adhesion (dependent on αIIbβ3 activation) is much higher for platelets on the combined dmA1A2 VWF/FN surface than on dmA1A2 VWF alone. Results shown are the summary of at least 3 experiments. *P < .05 in a Student t test for ADAP−/− platelets compared with ADAP+/+ platelets.

GP Ib-IX-V–induced αIIbβ3 activation under shear flow. Whole blood from ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice was adjusted to correct for thrombocytopenia of ADAP−/− mouse blood and aspirated over a coverslip coated with dmA1A2 VWF, with or without fibronectin (FN), and placed in a parallel plate flow chamber. The total number of platelets tethering to the surface was measured, and the percentage of these platelets that remained stationary for 3.5 seconds or 10 seconds was determined at 20 seconds, 1 minute, or 2 minutes after the initiation of flow. Results represent stationary platelets, as a percentage of the total number of platelets contacting the surface within the sampling time, ± SEM. (A) Platelets stationary for 3.5 seconds. (B) Platelets stationary for 10 seconds. Stationary adhesion (dependent on αIIbβ3 activation) is much higher for platelets on the combined dmA1A2 VWF/FN surface than on dmA1A2 VWF alone. Results shown are the summary of at least 3 experiments. *P < .05 in a Student t test for ADAP−/− platelets compared with ADAP+/+ platelets.

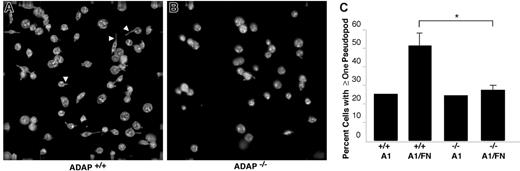

One consequence of αIIbβ3 interaction with ligands such as fibrinogen is outside-in signaling, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangements and the development of filopodial and lamellipodial extensions. In the absence of soluble agonists such as ADP, mouse platelets adherent to fibrinogen exhibit more filopodia and fewer lamellipodia compared with human platelets. Spreading of ADAP+/+ platelets on the combined dmA1A2 VWF/fibronectin surface under shear flow was limited mostly to filopodial extension (Figure 5A), a response that was reduced in ADAP−/− platelets (Figure 5B). Thus, while 51% ± 7% of ADAP+/+ cells showed one or more filopodia on dmA1A2 VWF/fibronectin, only 27% ± 3% of ADAP−/− platelets showed filopodia (Figure 5C; P < .05). No such difference between wild-type and knockout platelets was noted on dmA1A2 VWF alone (25% and 24%, respectively) (Figure 5B-C). Additionally, the filopodia of ADAP+/+ platelets on the combined surface tended to be longer than the few produced on the single surface or the ones exhibited by ADAP−/− platelets on either surface (Figure 5A-B). Altogether, these results indicate that ADAP+/+ platelets undergo GP Ib-IX-V–dependent activation of αIIbβ3 leading to increased filopodial extension, whereas such responses are considerably diminished in ADAP−/− platelets. The reduced length of filopodia in ADAP−/− platelets under shear flow adherent to the combined dmA1A2 VWF/fibronectin surface suggests that ADAP may additionally mediate αIIbβ3-dependent outside-in signals for cytoskeletal rearrangements.

Cytoskeletal rearrangements in response to adhesion to dmA1A2 VWF and fibronectin under shear flow. Platelets were allowed to interact with dmA1A2 VWF alone or together with FN as described in Figure 4. Cells were fixed after 2 minutes of flow, stained for αIIb, imaged by deconvolution microscopy, and scored for filopodial extensions. (A) ADAP+/+ or (B) ADAP−/− platelets adherent on the combined A1A2 VWF/FN surface. Arrowheads illustrate filopodia, which were shorter and less numerous in panel B. (C) Quantitative representation of the percentage of cells with filopodial protrusions on dmA1A2 VWF alone or together with FN ± SEM (*P < .05). Results shown are the summary of 3 separate experiments.

Cytoskeletal rearrangements in response to adhesion to dmA1A2 VWF and fibronectin under shear flow. Platelets were allowed to interact with dmA1A2 VWF alone or together with FN as described in Figure 4. Cells were fixed after 2 minutes of flow, stained for αIIb, imaged by deconvolution microscopy, and scored for filopodial extensions. (A) ADAP+/+ or (B) ADAP−/− platelets adherent on the combined A1A2 VWF/FN surface. Arrowheads illustrate filopodia, which were shorter and less numerous in panel B. (C) Quantitative representation of the percentage of cells with filopodial protrusions on dmA1A2 VWF alone or together with FN ± SEM (*P < .05). Results shown are the summary of 3 separate experiments.

To determine if ADAP is involved in αIIbβ3 activation downstream of excitatory receptors other than GP Ib-IX-V, platelets were stimulated with ADP, convulxin, or the Par4 receptor-activating peptide, AYPGKF. Platelets from ADAP+/+ mice bound FITC-fibrinogen in a dose-dependent manner in response to each agonist. By comparison, ADAP−/− platelets exhibited a 45% to 75% reduction in FITC-fibrinogen binding to ADP-activated platelets (P < .05) (Figure 6A), an approximately 75% reduction in binding to Par4 peptide-activated platelets (P < .01) (Figure 6B), and an approximately 15% to 29% reduction to convulxin-activated platelets (P < .05) (Figure 6C) despite normal αIIbβ3 expression (Figure 2C). Aggregation of stirred platelets stimulated with ADP or Par4 resulted in normal shape change in ADAP+/+ and ADAP−/− platelets. At lower agonist concentrations, ADAP−/− platelets showed an 18% to 50% decrease in the maximum aggregation at 2 minutes, and after 2 to 5 μM ADP the ADAP−/− platelets disaggregated while the wild-type platelets did not (not shown). Because ADAP deficiency impairs αIIbβ3 activation by several agonists, ADAP may transduce signals through modulators, such as talin, or stabilize signaling complexes that converge on the integrin cytoplasmic tails to modulate affinity.36,56 It has been suggested that talin interaction with integrins may be regulated by phosphorylation, binding of PIP2, or calpain-mediated proteolysis.57-60 ADAP could participate in talin regulation by increasing intracellular calcium levels and activating protein kinase C61 or calpain.59 Alternatively, ADAP might regulate access of PIP2 to talin by interacting with PIP2 through the ADAP extended helical SH3 domain.62 Finally, the small GTPase, Rap1, has been implicated in promoting ligand binding to integrins.63 Perhaps ADAP influences the localization of Rap1b effectors to talin. Further studies are required to assess these possibilities.

Soluble FITC-fibrinogen binding to platelets activated by ADP, Par4 receptor-activating peptide, or convulxin. Platelets were stimulated with varying concentrations of agonist, and the binding of soluble FITC-fibrinogen to platelets was determined by flow cytometry. ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− platelets stimulated with (A) ADP, (B) Par4, or (C) convulxin. Results are shown as the percentage of ADAP+/+ FITC-fibrinogen binding to ADAP+/+ cells for a given agonist concentration ± SEM (*P < .05; **P < .01). Results are a summary of at least 4 separate experiments.

Soluble FITC-fibrinogen binding to platelets activated by ADP, Par4 receptor-activating peptide, or convulxin. Platelets were stimulated with varying concentrations of agonist, and the binding of soluble FITC-fibrinogen to platelets was determined by flow cytometry. ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− platelets stimulated with (A) ADP, (B) Par4, or (C) convulxin. Results are shown as the percentage of ADAP+/+ FITC-fibrinogen binding to ADAP+/+ cells for a given agonist concentration ± SEM (*P < .05; **P < .01). Results are a summary of at least 4 separate experiments.

The ADAP-binding partner, SKAP-HOM, is not required for αIIbβ3 activation

ADAP and SKAP-HOM, its binding partner, have been detected in macromolecular complexes upon platelet activation through GP VI.64 In the process of evaluating ADAP-binding proteins, we discovered that SKAP-HOM protein levels were undetectable in ADAP−/− mouse platelets (Figure 7A). This is similar to observations that ADAP may be required for regulating levels of SKAP55 in a Jurkat T-cell line65 and SKAP-HOM levels in lymphocytes.66 To investigate whether ADAP can regulate SKAP-HOM independently of other proteins with which it may be associated in hematopoietic cells, we transfected CHO cells with expression vectors for each of these proteins. Very little SKAP-HOM protein was detected when it was transfected without ADAP (Figure 7B). However, SKAP-HOM was readily detected when cotransfected with ADAP. This was not observed with a SKAP-HOM mutant lacking the SH3 domain (Figure 7B). Thus, ADAP stabilizes SKAP-HOM protein levels in a manner dependent on the SKAP-HOM SH3 domain.

SKAP-HOM protein expression and function in ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice. (A) Washed platelets from ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice were lysed, subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis, and Western blotted for SKAP-HOM. Blots were then reprobed for ADAP and integrin β3, the latter to monitor gel loading. Two separate anti–SKAP-HOM antibodies were used to confirm results. (B) SKAP-HOM regulation by ADAP in CHO cells. CHO cells were transfected with 1 μg ADAP alone, 3 μg EGFP-SKAP-HOM or EGFP-SKAP-HOM lacking the SH3 domain (dSH3) alone, or a combination of ADAP and EGFP-SKAP-HOM. After 48 hours, cells were subjected to SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed for ADAP and SKAP-HOM. Platelet lysate from wild-type mice, prepared as in Figure 6A, was used as a positive control, and blots were reprobed with a β-actin antibody to monitor gel loading. (C) Platelets from wild-type or SKAP-HOM knockout mice were allowed to adhere to dmA1A2 VWF as described in Figure 2, and integrin activation was assessed by FITC-fibrinogen binding in the presence or absence of a cocktail of inhibitors or PMA. Results in panels A and B are representative of at least 3 experiments, with similar results. Results in panel C are for ADAP−/− platelets (white bars), depicted as a percentage of soluble ligand that is specifically bound by ADAP+/+ platelets (black bars) ± SEM, and are a summary of 3 separate experiments.

SKAP-HOM protein expression and function in ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice. (A) Washed platelets from ADAP+/+ or ADAP−/− mice were lysed, subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis, and Western blotted for SKAP-HOM. Blots were then reprobed for ADAP and integrin β3, the latter to monitor gel loading. Two separate anti–SKAP-HOM antibodies were used to confirm results. (B) SKAP-HOM regulation by ADAP in CHO cells. CHO cells were transfected with 1 μg ADAP alone, 3 μg EGFP-SKAP-HOM or EGFP-SKAP-HOM lacking the SH3 domain (dSH3) alone, or a combination of ADAP and EGFP-SKAP-HOM. After 48 hours, cells were subjected to SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed for ADAP and SKAP-HOM. Platelet lysate from wild-type mice, prepared as in Figure 6A, was used as a positive control, and blots were reprobed with a β-actin antibody to monitor gel loading. (C) Platelets from wild-type or SKAP-HOM knockout mice were allowed to adhere to dmA1A2 VWF as described in Figure 2, and integrin activation was assessed by FITC-fibrinogen binding in the presence or absence of a cocktail of inhibitors or PMA. Results in panels A and B are representative of at least 3 experiments, with similar results. Results in panel C are for ADAP−/− platelets (white bars), depicted as a percentage of soluble ligand that is specifically bound by ADAP+/+ platelets (black bars) ± SEM, and are a summary of 3 separate experiments.

SKAP55, a protein homologous to SKAP-HOM, is not expressed in platelets.64 However, it associates with ADAP in T cells20 and has been implicated in integrin-mediated T-cell adhesion.27,28 Therefore, the absence of SKAP-HOM in ADAP−/− platelets raised the possibility that it and not ADAP is required for αIIbβ3 activation. To address this possibility, SKAP-HOM−/− mice were studied.40 These mice exhibited platelet numbers and levels of platelet ADAP similar to wild-type littermates. However, unlike the results with ADAP−/− platelets, SKAP-HOM−/− platelets bound fibrinogen normally after adhesion to dmA1A2 VWF or stimulation with PMA (Figure 7C). In addition, SKAP-HOM−/− platelets bound FITC-fibrinogen normally in response to 10 μM ADP or 250 μM Par4 receptor-activating peptide (not shown). Thus, ADAP and not SKAP-HOM is required for signaling through GP Ib-IX-V and other agonists to αIIbβ3.

Taken together, these experiments establish that ADAP is involved in (1) normal GP Ib-IX-V–induced signaling to αIIbβ3, both under static and shear flow conditions; (2) αIIbβ3 activation downstream of agonists acting through G-protein–coupled receptors; (3) regulation of platelet expression of SKAP-HOM; and (4) normal platelet function in vivo as assessed by rebleeding from tail wounds. Thus, ADAP deficiency has several consequences for platelet function through the promotion of integrin activation and stable adhesion under shear flow. This discovery raises new questions. Does the increased frequency of rebleeding from tail wounds in ADAP−/− mice mean that defects in GP Ib-IX-V signaling can lead to unstable thrombi in vivo? If so, would it be possible to selectively block this signaling pathway to achieve an antithrombotic effect with minimal disruption of hemostasis? Does ADAP influence platelet function through interactions with known modulators of αIIbβ3 affinity, such as talin or Rap1b, or does it regulate αIIbβ3 affinity by a novel mechanism? The answers to these questions will illuminate how one major class of platelet adhesion receptor communicates with another.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K.-F. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; B.M. and J.N.-O. collected data; K.S. and B.S. supplied vital reagents; Z.M.R. supplied vital reagents, designed research, and wrote the paper; B.G.N. and G.K. supplied vital reagents and wrote the paper; and S.J.S. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ana Kasirer-Friede, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr, Mail Code 0726, La Jolla, CA 92093-0726; e-mail: akasirer@ucsd.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL31950, HL42846, HL7874, HL78784, DK50654-09), the German Research Foundation, German Israelian Foundation, and the state of Saxony-Anhalt and an American Heart Association fellowship (0425107Y).

The authors are grateful to Drs Barry Coller and Mark Ginsberg for supplying reagents.