Abstract

During erythroid differentiation and maturation, it is critical that the 3 components of hemoglobin, α-globin, β-globin, and heme, are made in proper stoichiometry to form stable hemoglobin. Heme-regulated translation mediated by the heme-regulated inhibitor kinase (HRI) provides one major mechanism that ensures balanced synthesis of globins and heme. HRI phosphorylates the α-subunit of eukaryotic translational initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) in heme deficiency, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis globally. In this manner, HRI serves as a feedback inhibitor of globin synthesis by sensing the intracellular concentration of heme through its heme-binding domains. HRI is essential not only for the translational regulation of globins, but also for the survival of erythroid precursors in iron deficiency. Recently, the protective function of HRI has also been demonstrated in murine models of erythropoietic protoporphyria and β-thalassemia. In these 3 anemias, HRI is essential in determining red blood cell size, number, and hemoglobin content per cell. Translational regulation by HRI is critical to reduce excess synthesis of globin proteins or heme under nonoptimal disease states, and thus reduces the severity of these diseases. The protective role of HRI may be more common among red cell disorders.

Introduction

Mature red blood cells (RBCs) are packed with a very high concentration of hemoglobin, approximately 5 mM in both humans and mice. Thus, during erythroid differentiation and maturation, it is critical that the 3 components of hemoglobin, α-globin, β-globin, and heme, are made in the 2:2:4 ratio in order to form stable α2β2 hemoglobin complexed with 4 heme molecules. Imbalance of these 3 components can be deleterious since each component is cytotoxic to RBCs and their precursors. The importance of equimolar concentration of α- and β-globin proteins is best illustrated by the prevalent human red cell disease of thalassemia, and the significance of the globin-heme ratio is well demonstrated by the hypochromic anemia in iron deficiency.

Iron and heme play very important roles in hemoglobin synthesis and erythroid cell differentiation (reviewed in Ponka1 and Taketani2 ). Heme iron accounts for the majority of iron in the human body, and hemoglobin (the most abundant hemoprotein) contains as much as 70% of the total iron content of a healthy adult. In addition to serving as a prosthetic group for hemoglobin, heme also regulates the transcription of globin genes through its binding to the transcriptional factor Bach1 during erythroid differentiation (reviewed in Taketani2 and Igarashi and Sun3 ). Furthermore, heme controls the translation in erythroid precursors by modulating the eIF2α kinase activity of the heme-regulated eIF2α kinase, HRI (reviewed in Chen4 ). Recently, we have found that this translational regulation of HRI is essential to reduce excessive synthesis of globin proteins and phenotypic severities in the anemias of iron deficiency,5 erythropoietic protoporphyria, and β-thalassemia.6 Most significantly, HRI is responsible for the morphologic hypochromia and microcytosis of these 3 anemias. In this review, I focus on the recent advances in our understanding of the functions of HRI in the stress erythropoiesis that occurs in anemia.

Inhibition of protein synthesis by HRI in heme deficiency

HRI, the heme-regulated inhibitor of translation, was discovered in reticulocytes under the conditions of iron and heme deficiencies, which cause inhibition of protein synthesis at initiation with disaggregation of polysomes.7-12 HRI was later shown to be the heme-regulated eIF2α kinase phosphorylating the α-subunit of eIF213,14 (and reviewed in Chen4 ), a key regulatory translation initiation factor.

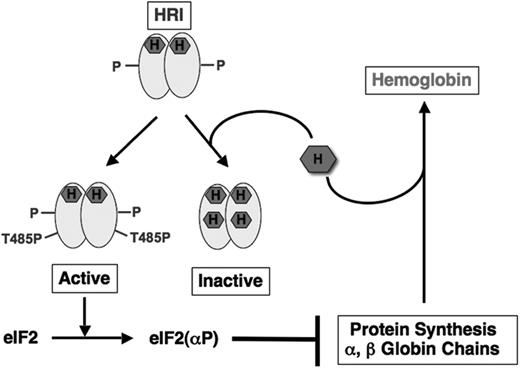

In heme deficiency, HRI is activated by multiple autophosphorylation.15-20 Autophosphorylation is also important in the formation of active, stable HRI that is regulated by heme and, therefore, senses intracellular heme concentration. Our biochemical studies have led us to propose that newly synthesized HRI with heme incorporated in its N-terminus domain rapidly dimerizes and undergoes intermolecular multiple autophosphorylation in heme deficiency in 3 stages (Figure 1). In the first stage, autophosphorylation of newly synthesized HRI stabilizes HRI against aggregation. At this stage, HRI is an active autokinase, but is without eIF2α kinase activity. Additional autophosphorylation (denoted by P in Figure 1) in the second stage is required for the formation of stable dimeric HRI that is regulated by heme.19 As shown in Figure 1, in heme abundance, heme binds to this stable HRI and represses HRI activation.21 In heme deficiency, HRI undergoes the final stage of autophosphorylation at Thr485 (T485P) and attains eIF2α kinase activity. This fully activated HRI is no longer regulated by heme, and is degraded.22

HRI balances heme and globin synthesis by sensing intracellular heme concentrations. During the synthesis of hemoglobin, one molecule of heme is incorporated into each globin chain. When heme concentration is high, heme binds to the second heme-binding domain of HRI and keeps HRI in inactive state, thereby permitting globin protein synthesis and the formation of stable hemoglobin. In heme deficiency, HRI is activated by autophosphorylation. Activated HRI phosphorylates eIF2α and inhibits globin protein synthesis by the mechanism illustrated in Figure 2. HRI, therefore, acts as a feedback inhibitor of globin synthesis to ensure no globin is translated in excess of the heme available for assembly of stable hemoglobin.

HRI balances heme and globin synthesis by sensing intracellular heme concentrations. During the synthesis of hemoglobin, one molecule of heme is incorporated into each globin chain. When heme concentration is high, heme binds to the second heme-binding domain of HRI and keeps HRI in inactive state, thereby permitting globin protein synthesis and the formation of stable hemoglobin. In heme deficiency, HRI is activated by autophosphorylation. Activated HRI phosphorylates eIF2α and inhibits globin protein synthesis by the mechanism illustrated in Figure 2. HRI, therefore, acts as a feedback inhibitor of globin synthesis to ensure no globin is translated in excess of the heme available for assembly of stable hemoglobin.

Using Hri−/− mice, we have demonstrated that Hri−/− reticulocytes had a higher rate of protein synthesis with larger sized polysomes when compared with Hri+/+ reticulocytes.5 Furthermore, protein synthesis in Hri−/− reticulocytes was no longer affected by hemin. Thus, in the absence of HRI, the steady-state level of protein synthesis in reticulocytes is considerably increased in a heme-independent manner with the primary impact on the synthesis of α- and β-globin chains, the most abundant proteins translated in these cells.5 These results provide the in vivo evidence for the roles of HRI and heme in the regulation of translational initiation in erythroid precursors (Figure 1).

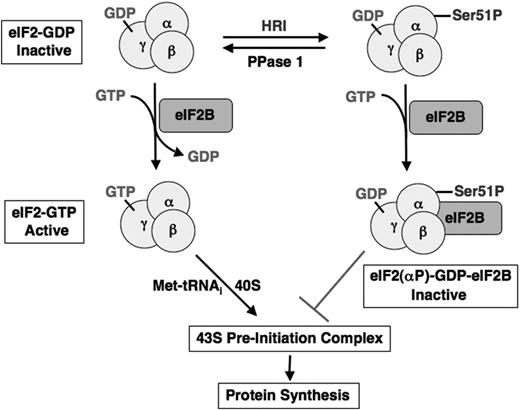

The molecular mechanism of inhibition of translational initiation by the phosphorylation of eIF2α has been studied extensively (reviewed in Hinnebusch23 and Hershey and Merrick24 ), and is illustrated in Figure 2. eIF2 is a heterotrimeric protein that binds GTP, initiating Met-tRNAi and the small 40S ribosomal subunit to form the 43S preinitiation complex. In vivo, eIF2 exists in 2 forms, the inactive eIF2-GDP and the active eIF2-GTP. The GTP in the eIF2-GTP complex is hydrolyzed to GDP upon binding of the large 60S ribosomal subunit to the 43S preinitiation complex during translation. The recycling of eIF2 for another round of translational initiation, therefore, requires the exchange of its bound GDP for GTP. However, eIF2 has a 400-fold greater affinity for GDP than for GTP under physiological conditions. This exchange of tightly bound GDP for GTP requires another initiation factor, eIF2B, which is rate limiting with a concentration of 15% to 25% of eIF2. When eIF2α is phosphorylated by HRI at Ser51, the phosphorylated eIF2(αP)–GDP binds much more tightly to eIF2B than eIF2- GDP does and prevents the GDP/GTP exchange activity of eIF2B.25 Thus, once the amount of phosphorylated eIF2 exceeds the amount of eIF2B, protein synthesis is shut off. The inhibitory effect of HRI on protein synthesis is reversed following heme repletion. This recovery of protein synthesis requires not only the inhibition of HRI by heme but also the removal of the inhibitory phosphate at Ser51 of eIF2α by type 1 phosphatase (PPase 1)26-30 to regenerate the active eIF2-GTP.

Inhibition of the recycling of eIF2 by HRI during translational initiation. eIF2 is a heterotrimeric protein with GTP/GDP-binding site on the γ-subunit. In the initiation of translation, active eIF2-GTP binds initiating methionyl-tRNA and 40S ribosomal subunit to form 43S preinitiation complex. Upon the joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit, GTP bound to eIF2 is hydrolyzed to GDP as an energy source for the joining reaction to form 80S initiating ribosome. To recycle eIF2 for another round of initiation, it is necessary to exchange the bound GDP for GTP. This exchange reaction is catalyzed by another initiation factor eIF2B, which is present in a limiting amount. When eIF2 is phosphorylated by HRI on the Ser51 of the α-subunit, it binds to eIF2B tightly and inactivates eIF2B activity. Depletion of functional eIF2B, therefore, keeps eIF-2 strained in the inactive GDP state and inhibits protein synthesis.

Inhibition of the recycling of eIF2 by HRI during translational initiation. eIF2 is a heterotrimeric protein with GTP/GDP-binding site on the γ-subunit. In the initiation of translation, active eIF2-GTP binds initiating methionyl-tRNA and 40S ribosomal subunit to form 43S preinitiation complex. Upon the joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit, GTP bound to eIF2 is hydrolyzed to GDP as an energy source for the joining reaction to form 80S initiating ribosome. To recycle eIF2 for another round of initiation, it is necessary to exchange the bound GDP for GTP. This exchange reaction is catalyzed by another initiation factor eIF2B, which is present in a limiting amount. When eIF2 is phosphorylated by HRI on the Ser51 of the α-subunit, it binds to eIF2B tightly and inactivates eIF2B activity. Depletion of functional eIF2B, therefore, keeps eIF-2 strained in the inactive GDP state and inhibits protein synthesis.

Family of eIF2α kinases

Phosphorylation of eIF2α occurs under various stress conditions in addition to heme deficiency. Recently, it has been shown that pre-emptive phosphorylation of eIF2α can protect cells from oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stresses.31 In addition to HRI, 3 other eIF2α kinases are known: the double-stranded RNA-dependent eIF2α kinase (PKR), the GCN2 protein kinase, and the ER resident kinase (PERK). The 4 eIF2α kinases share extensive homology in their kinase catalytic domains32-38 and phosphorylate eIF2α at the same Ser51 residue.37-40 While they share a common mode of action, each elicits a different physiological response as a consequence of distinctive tissue distributions and the different signals to which they respond via their unique regulatory domains.

PKR responds to viral infection (reviewed in Kaufman41 ), while GCN2 senses nutrient starvations (reviewed in Hinnebusch42 ). PERK is activated by ER stress (reviewed in Ron and Harding43 ), and HRI is regulated by heme. The unique function of each of these eIF2α kinases in response to different stresses has been verified by generations of knock-out mice with each of the 4 eIF2α kinases.5,44-47 Pkr−/− mice are compromised in their ability to respond to viral challenges,44,48 and Perk−/− mice develop diabetes between 2 and 4 weeks of age.45 Gcn2−/− mice have reduced viability upon amino acid starvation,46 and we have demonstrated that the erythroid response to iron and heme deficiency is abnormal in Hri−/− mice.5,6

Regulation of HRI by heme

Both autokinase and eIF2α kinase activities of purified homogeneous HRI were inhibited by hemin with an apparent Ki of 0.2 μM.18,19 It is interesting to note that this heme-binding affinity of HRI is on the same order as those of Bach1 and heme oxygenase 1.3 Hemin inhibits ATP binding to HRI in a concentration-dependent manner,49 thus blocking the kinase activities of HRI. Biochemical studies have demonstrated that HRI has 2 distinct types of heme-binding sites.18 One type of binding site is nearly saturated with stably-bound endogenous heme and copurifies with HRI, while the other binding site is available to bind exogenous hemin reversibly (Figures 1 and 3). This second reversible heme-binding site is likely to be responsible for the down-regulation of HRI activity by heme. The stoichiometry of 2 heme molecules per HRI monomer was established recently by direct measurement of heme chromophor.19

Protein structure of HRI. HRI is divided into 5 domains as indicated. The amino acid sequence of mouse HRI is used here. Heme molecules are marked in red; S denotes the stable heme-binding site, while R denotes the reversible heme-binding site. *Histidine residues that coordinate the heme molecule.

Protein structure of HRI. HRI is divided into 5 domains as indicated. The amino acid sequence of mouse HRI is used here. Heme molecules are marked in red; S denotes the stable heme-binding site, while R denotes the reversible heme-binding site. *Histidine residues that coordinate the heme molecule.

As illustrated in Figure 3, HRI has 3 unique regions, the N-terminus, the kinase insert (KI) domain, and the C-terminus. Both the N-terminus and KI can bind heme, whereas the kinase catalytic domains (kinase I, kinase II) and the C-terminus cannot.21 In addition, the N-terminus is necessary for stable high-affinity heme binding to HRI, and is also required for achieving higher eIF2α kinase activity, although it is not essential for the kinase activity of HRI. Of most importance, the N-terminus is essential for the highly sensitive heme regulation of HRI. The N-terminally truncated HRI has a 10-fold higher apparent Ki by heme.21

It has been shown that heme binds to several hemoproteins such as δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase,50 Hap1,51 and Bach152 through the heme regulatory motif (HRM). The HRM consists of Cys-Pro dipeptide in which Cys is essential for heme ligation. There are 2 such putative HRMs, Cys409-Pro410 and Cys550-Pro 551, in mouse HRI. However, they are unlikely to participate in the heme regulation of HRI for the following reasons. First, mutation of these 2 Cys residues individually to Ser had no apparent effect on the heme responsiveness of HRI.21 Second, these 2 Cys residues are not conserved in chicken, Xenopus, or fish HRI,53,54 indicating that they may not be important for heme regulation of HRI. Third, our recent electron paramagnetic resonance and resonance Raman spectroscopic studies demonstrate that heme molecules in both the N-terminus and KI domains are 6-coordinated by the nitrogen groups of histidines (Bettina Bauer and J.-J.C., unpublished observations, September 2003).

Conserved His75 and His120 of HRI were the proximal and distal heme ligand, respectively, in the N-terminus domain55,56 (Bettina Bauer and J.-J. C., unpublished observations, October 2002). Mutation of His75 and His120 individually to Ala in the full-length HRI resulted in decreased sensitivity to heme inhibition, similar to N-terminally truncated HRI (Andrew Yen and J.-J.C., unpublished observations, January 2004), further underscoring the importance of heme in the N-terminus for the down-regulation of HRI activity. This raises an important question of the function of the high-affinity heme binding in the N-terminus domain. Our biochemical studies suggest that heme may be incorporated into the N-terminus domain of HRI cotranslationally or soon after synthesis (Figure 1), similar to the assembly of heme into globin chains.57 Ligation of heme in the N-terminus might be important for subsequent correct folding to generate stable heme-regulated HRI or for the stability of the HRI protein.

Role in iron-deficiency anemia

In the formation of stable α2β2 hemoglobin, it is important to keep the concentrations of globin chains and heme balanced. Globin chains misfold and precipitate in the absence of proper binding to heme, as observed in vitro58,59 and in vivo of unstable hemoglobins caused by mutations that decrease heme incorporation.60,61 Biochemical and in vitro studies described in “Regulation of HRI by heme” suggest that HRI may serve as a feedback inhibitor of globin synthesis to balance heme and globin synthesis by sensing heme availability as illustrated in Figure 1. This hypothesis has been proven by studies of the Hri−/− mice in iron deficiency.5

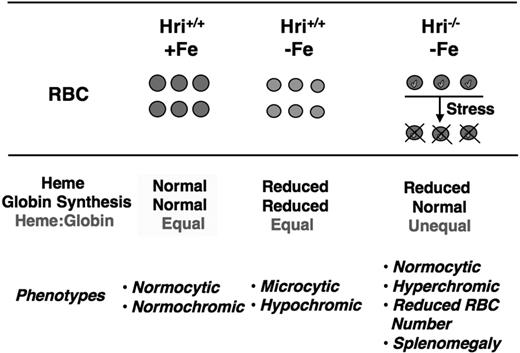

Iron deficiency is very common, with an incidence of approximately 2 billion cases worldwide.62 The normal adaptive response to iron deficiency in humans and mice is the well-characterized microcytic hypochromic anemia with decreased mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) in RBCs (Figure 4). In Hri−/− mice, this physiological response to iron deficiency was dramatically altered. These mice develop a very unusual pattern of slight hyperchromic normocytic anemia with an accentuated decrease in RBC counts. Thus, HRI is critical in determining red blood cell size, cell number, and hemoglobin content per cell. HRI is solely responsible for the adaptation of microcytic hypochromic anemia in iron deficiency.

HRI is responsible for the adaptation of microcytic hypochromic anemia in iron deficiency. In iron deficiency, heme concentration declines, which leads to HRI activation and inhibition of globin synthesis as illustrated in Figure 1. This results in decreased hemoglobin and total protein content in Hri+/+ RBCs. In the absence of HRI (Hri−/−), protein synthesis continues in the face of heme deficiency, resulting in excess globins. These heme-free globins are unstable and precipitate as inclusions (marked in green) in RBCs and their precursors, causing destruction of these cells. Hri−/− RBCs are of normal cell size and slightly hyperchromic. However, Hri−/− mice have decreased RBC number, reticulocytosis, and splenomegaly.

HRI is responsible for the adaptation of microcytic hypochromic anemia in iron deficiency. In iron deficiency, heme concentration declines, which leads to HRI activation and inhibition of globin synthesis as illustrated in Figure 1. This results in decreased hemoglobin and total protein content in Hri+/+ RBCs. In the absence of HRI (Hri−/−), protein synthesis continues in the face of heme deficiency, resulting in excess globins. These heme-free globins are unstable and precipitate as inclusions (marked in green) in RBCs and their precursors, causing destruction of these cells. Hri−/− RBCs are of normal cell size and slightly hyperchromic. However, Hri−/− mice have decreased RBC number, reticulocytosis, and splenomegaly.

There were marked expansions of erythroid precursors in the bone marrow and spleen of iron-deficient Hri−/− mice. In addition, reticulocyte counts in the blood were significantly elevated in these mice, providing additional evidence for erythroid hyperplasia. There was no apparent difference in the survival of RBCs from Wt and Hri−/− mice whether on normal or iron-deficient diets. However, there was an increase in apoptosis of late erythroid precursors in iron-deficient Hri−/− mice. Thus, HRI is also essential for the survival of erythroid precursors in iron deficiency.

Multiple variably sized globin inclusions were observed within reticulocytes and, to a lesser extent, within fully mature RBCs in iron-deficient Hri−/− mice as summarized in Figure 4. Together, studies of Hri−/− mice in iron deficiency uncovered the function of HRI in coordinating the synthesis of globins in RBC precursors to the concentration of heme in vivo (Figures 1 and 4). HRI normally ensures that no globin chains are translated in excess of what can be assembled into hemoglobin tetramers for the amount of heme available. In the absence of HRI, heme-free globins precipitate in iron deficiency and become a major cell destruction component in the pathophysiology of the iron-deficiency anemia.5 Moreover, the survival rate of iron-deficient Hri−/− mice upon phenylhydrazine-induced erythroid stress was dramatically reduced.5

Role in erythropoietic protoporphyria

The importance of HRI in the pathophysiology of heme-deficiency disorders was revealed recently by generating mice with combined deficiencies of HRI and ferrochelatase (Fech). Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice have a point mutation in Fech at amino acid 98 from Met to Lys, resulting in a dramatic decrease of its enzyme activity to only 3% to 6% of the Wt.63 Since Fech (the last enzyme of heme biosynthesis) inserts iron into protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) to form heme, Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice are functionally heme deficient, and accumulate PPIX, similar to the human disease of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).63,64 HRI was activated in Fechm1Pas/m1Pas reticulocytes, providing the in vivo evidence that HRI is regulated directly by heme and not by iron.6

In the presence of HRI, Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice had a microcytic hypochromic anemia. These mice became significantly more anemic in HRI deficiency. However, the MCV and MCH were not significantly decreased in HRI deficiency; the decreased hemoglobin was due to an overall decrease in the number of normochromic, normocytic RBCs, similar to the unusual effect of HRI deficiency on the normally microcytic anemia of iron deficiency.5 Furthermore, inclusion bodies were seen in reticulocytes from HRI-deficient Fechm1Pas/m1Pas animals. Both α- and β-globin proteins were present in the inclusions, consistent with the global inhibition of protein synthesis by HRI in heme deficiency. Furthermore, both copies of HRI were necessary to inhibit fully the accumulation of excess heme-free α- and β-globins in heme-deficient Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice. The morphologically and biochemically similar red cell abnormalities elicited by the absence of HRI both in iron and heme deficiencies further underscore the importance of HRI in inhibiting protein synthesis to avoid accumulation of excess heme-free α- and β-globins in heme-deficiency states.

Although Hri−/−Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice were viable, they were smaller in size and appeared severely jaundiced. Most significantly, PPIX levels were dramatically increased by 30-fold in the RBCs and reticulocytes of Hri−/−Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice compared with Hri+/+Fechm1Pas/m1Pas controls. Furthermore, Fechm1Pas/m1Pas animals lacking one copy of HRI also had significantly increased PPIX levels (4.5-fold). Compared with heme, PPIX is a poor inhibitor of HRI.65 Consequently, excessive PPIX biosynthesis in Hri−/−Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice is likely due to the inability of translational inhibition in heme deficiency. Sustained protein synthesis of the heme biosynthetic enzymes contributes to the excessive PPIX synthesis in Hri−/−Fechm1Pas/m1Pas animals, further demonstrating the role of HRI in globally regulating red cell protein expression. In this manner, HRI regulates not only globin synthesis, but also heme biosynthesis.

While the erythron is the major source of excess PPIX in EPP, the primary clinical complications are hepatocellular toxicity and skin photosensitivity (reviewed in Sassa and Kappas66 ). Similar to human patients with EPP, Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice have hepatomegaly, hepatic porphyrin deposits, and photosensitivity.63 These abnormalities were more severe in HRI-deficient animals lacking even one copy of HRI. As described in the preceding paragraph, both copies of HRI are necessary to reduce excess synthesis of PPIX in erythroid precursors, thereby reducing PPIX accumulation in the liver and cutaneous photosensitivity. It is well established that a small fraction (2%) of EPP patients develop fatal hepatic pathology (reviewed in Sassa and Kappas66 ). The molecular mechanism for this severe phenotypic expression is unknown, but does not appear to be necessarily related to the specific disease allele.66,67 The more severe pathology of the Hri−/−Fechm1Pas/m1Pas mice indicates that HRI may be a significant modifier gene contributing to EPP disease severity, particularly in the development of hepatic pathology.

Activation of HRI by stresses other than heme deficiency

While each of the 4 eIF2α kinases has its specific stress signal as described in “Family of eIF2α kinases,” it is not clear which eIF2α kinase(s) is activated upon more general stresses such as oxidative stress, heat shock, and osmotic shock. In addition to HRI, both PKR68 and GCN220 are expressed in erythroid precursors. Using Hri−/− erythroid precursors, we have established that HRI was activated by arsenite-induced oxidative stress, osmotic shock, and heat shock, but not by ER stress, or amino acid or serum starvation in heme-sufficient reticulocytes and nucleated fetal liver erythroid precursor cells.20 These observations are consistent with the specific functions of PERK and GCN2 for ER stress and nutrient starvation, respectively. Of most importance, HRI is the only eIF2α kinase activated by arsenite and is the major eIF2α kinase responsible for heat shock response in erythroid cells.20 Activation of HRI by arsenite involves reactive oxygen species and requires molecular chaperone hsp70 and hsp90.20

Role in β-thalassemia intermedia

In view of the activation of HRI under nonheme stress, HRI may protect erythroid cells against stress in general and may play a role in the physiological response to RBC disorders beyond iron and heme deficiency. To begin investigating this, we chose to study the role of HRI in β-thalassemia intermedia because it displayed oxidative stress and denatured globins, both of which could activate HRI. Indeed, HRI was activated in the blood cells of β-thalassemic Hbb−/− mice, which lack both copies of β-globin major.70 We found that HRI was necessary for the survival of Hbb−/− mice. Beginning at E15.5, double knock-out embryos were very pale and smaller in size, and died uniformly by E18.5 of severe anemia.6

Erythropoiesis in mice undergoes switching during embryonic development. Starting at E8, macrocytic, nucleated primitive erythrocytes containing embryonic hemoglobin (α2y2) are produced in the yolk sac. Definitive (adult) erythropoiesis, which produces enucleated, normocytic erythrocytes expressing α-globin and β-major globin and a small amount of β-minor globin (adult globins, α2β

Similar to human β-thalassemia intermedia, Hbb−/− mice had a severe microcytic hypochromic anemia.5 The anemia was more severe in Hbb−/− mice lacking one copy of HRI. Furthermore, these mice had more inclusions in their reticulocytes and RBCs. The inclusions in the Hbb−/− blood samples were almost entirely composed of α-globin chains despite the presence of βminor-globin in the soluble hemoglobin. Therefore, activation of HRI is critical in minimizing the production and the accumulation of denatured α-globin aggregates; of importance, both copies of HRI are required for this function. Thalassemic syndromes are often complicated by splenomegaly, cardiomegaly, and iron overload. Each of these syndromes was more severe in HRI deficiency. In addition, the lifespan of Hri+/−Hbb−/− mice was compromised and the fertility was significantly decreased. All together, these results demonstrate that HRI plays a critical role in modifying the β-thalassemic phenotype in mice. These studies also suggest that HRI may be a modifier gene that influences the outcome of β-thalassemia in humans.6 In fact, HRI exhibited the most drastic nonglobin modifier effect in mouse β-thalassemic models to date.

HRI/eIF2αP signaling pathway in stress erythropoiesis of anemia

As discussed, the essential protective role of HRI in these 3 anemias is achieved by activation of the HRI/eIF2αP signaling pathway to inhibit globin synthesis (Figure 1–2). However, in addition to inhibition of global protein synthesis, the second important consequence of eIF2α phosphorylation is the reprogramming of the translation and transcription of genes required for stress response, and is termed “integrated stress response”71 (and reviewed in Proud72 and Holcik and Sonenberg73 ) (Figure 5). Under integrated stress response, a specific increase in the translation of transcriptional factors is observed amid inhibition of general protein synthesis by eIF2α phosphorylation. The best example of this type of translational up-regulation has been documented in amino acid starvation of yeast in which GCN2 is activated and the expression of the transcriptional activator GCN4 is up-regulated to induce the enzymes of amino acid biosynthetic pathways. This up-regulation requires the presence of upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in the 5′-UTR of GCN4 mRNA (reviewed in Hinnebusch23 ).

Proposed roles of HRI signaling pathway in stress erythropoiesis. Upon stress in erythroid cells, HRI is activated first to inhibit protein synthesis in order to reduce toxic globin precipitates. We propose that HRI also participates in the second arm of defense by increasing expression of specific genes such as Chop and GADD34, necessary for the adaptation to stress conditions. However, when the stress is insurmountable, this signaling pathway can also lead to apoptosis. In the absence of HRI, excess globins form inclusions and lead to hemolysis as well as apoptosis of erythroid precursors. Consequently, ineffective erythropoiesis occurs.

Proposed roles of HRI signaling pathway in stress erythropoiesis. Upon stress in erythroid cells, HRI is activated first to inhibit protein synthesis in order to reduce toxic globin precipitates. We propose that HRI also participates in the second arm of defense by increasing expression of specific genes such as Chop and GADD34, necessary for the adaptation to stress conditions. However, when the stress is insurmountable, this signaling pathway can also lead to apoptosis. In the absence of HRI, excess globins form inclusions and lead to hemolysis as well as apoptosis of erythroid precursors. Consequently, ineffective erythropoiesis occurs.

In mammalian cells, ATF4 is up-regulated upon ER stress and amino acid starvation.38,74 Like GCN4, ATF4 also contains uORFs, which are essential for its translational activation when eIF2α is phosphorylated.75,76 A major target gene of ATF4 is the transcriptional factor C/EBP homologous protein-10 (Chop, also known as GADD153), which is up-regulated transcriptionally in a wide variety of cells by many stresses.77,78 In ER stress, induction of Chop leads to the expression of GADD34, which recruits eIF2αP for dephosphorylation by PPase 1.26-29 This action of GADD34 in regenerating active eIF2 (Figure 2) is necessary for the recovery of protein synthesis of stress-induced gene expression that occurs late in stress response.30

The accumulations of globin aggregates in HRI-deficient erythroid precursors upon stress demonstrate the critical function of HRI in cytoplasmic unfolded protein response (UPR), similar to the role of PERK in UPR of ER stress. Of interest, knock out of ATF4 gene in mice resulted in transient fetal anemia with relatively normal erythropoiesis in adulthood.79 Additionally, Chop expression was increased upon exposure to erythropoietin, and was also up-regulated in mouse erythroleukemic (MEL) cells upon induction of erythroid differentiation by DMSO.80 We have found recently that Chop expression in erythroid precursors of fetal livers was induced by arsenite stress. Of importance, this induction of Chop was dependent on the presence of HRI; Chop induction was not seen in Hri−/− cells (Rajasekkhar Suragani and J.-J.C., unpublished observations, February 2006). Furthermore, recent studies of Gadd34−/− mice revealed that GADD34 was required for hemoglobin synthesis.81 Gadd34−/− mice developed mild microcytic hypochromic anemia and had a higher level of eIF2αP in their reticulocytes, establishing the function of GADD34 in the dephosphorylation of eIF2αP in erythroid cells. Together, these findings indicate that HRI is likely to activate a second arm of stress response in nucleated erythroid precursors in order to reduce ineffective erythropoiesis. It will be important to investigate whether HRI affects the expression of erythroid transcriptional factors such as GATA-1, Fog-1, NF-E2, or Bach1.

Pivotal role in microcytic hypochromic anemia

Since HRI is necessary for the phenotypic expression of the microcytic hypochromic anemias of iron deficiency, EPP and β-thalassemia, activation of HRI may be a hallmark of this type of anemia. The state of HRI may, therefore, affect the outcome of the anemia characterized by microcytosis and hypochromia. Besides the 3 anemias described here, HRI may also modify all other types of thalassemia, sideroblastic anemia, and unstable hemoglobin hemolytic anemia. Similarly to EPP and β-thalassemia, the clinical severities of these anemias are also quite heterogeneous.

Concluding remarks

Recent studies have established the essential protective role of HRI in 3 anemias, iron deficiency anemia, EPP, and β-thalassemia intermediates. The hallmarks of HRI deficiency in these 3 anemias are increased globin inclusions, decreased red blood cell number with normal MCV and MCH, and aggravation of ineffective erythropoiesis. HRI is therefore critical upon erythroid stress in safeguarding the proper cell size, cell number, and hemoglobin content of RBCs. Moreover, HRI may play a broader role in many red cell diseases involving heme and globin synthesis. To date, no human disease has yet been linked to HRI gene at chromosome 7p13q. The recent advancement of HRI studies thus warrants the search for possible mutations in the HRI gene in cases of hematologic syndromes of unknown origin in which normocytic normochromic anemia is observed in iron deficiency with inclusions in RBC and late erythroid precursors. It is also important to examine HRI as a modifier gene in EPP, thalassemia, and other anemias in human patients. This can be achieved initially by monitoring the eIF2αP in the erythroid precursors as an indicator of HRI activity. Future research on the second arm of the adaptive response of HRI signaling pathway inducing gene expressions unique to erythroid cells will be helpful in furthering our understanding of the molecular mechanism of ineffective erythropoiesis, which is the source of major complications in many anemias.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jane-Jane Chen, E25-545, MIT, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139; e-mail: j-jchen@mit.edu.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive & Kidney Diseases (DK16272 and DK 53223).

I would like to thank Dr Clara Camaschella (Internal Medicine, University Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Italy), Dr Lee Gehrke (HST, MIT), Mr Albert Liau (Biophysics program, University of California, Berkeley), and Drs Sijin Liu and Rajasekhar N. V. S. Suragani, from my laboratory, for their critical reading of this review.