Abstract

The transcription factor NF-κB is a tightly regulated positive mediator of T- and B-cell development, proliferation, and survival. The controlled activity of NF-κB is required for the coordination of physiologic immune responses. However, constitutive NF-κB activation can promote continuous lymphocyte proliferation and survival and has recently been recognized as a critical pathogenetic factor in lymphoma. Various molecular events lead to deregulation of NF-κB signaling in Hodgkin disease and a variety of T- and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas either upstream or downstream of the central IκB kinase. These alterations are prerequisites for lymphoma cell cycling and blockage of apoptosis. This review provides an overview of the NF-κB pathway and discusses the mechanisms of NF-κB deregulation in distinct lymphoma entities with defined aberrant pathways: Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (ATL). In addition, we summarize recent data that validates the NF-κB signaling pathway as an attractive therapeutic target in T- and B-cell malignancies.

Introduction

The development, maintenance, and progression of malignant lymphomas depend mechanistically on a deregulation of cellular pathways that control differentiation, proliferation, or apoptosis in lymphocytes. One essential and tightly regulated signaling cascade that mediates development, activation, and survival of normal lymphocytes for regulated immune responses is the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. In recent years it is becoming clear that aberrant deregulated NF-κB activation is a hallmark of several lymphoid malignancies and is directly linked to advanced disease. Several lymphoma types depend on NF-κB activity for cell cycling and survival, indicating that an inhibition of this pathway could be a therapeutic option. Here, we review the central components and the molecular regulation of NF-κB signaling as well as summarize mechanisms and consequences of aberrant NF-κB activation in distinct lymphoma entities, together with experimental data that validate the NF-κB pathway as a therapeutic target in lymphoma.

Physiology of NF-κB signaling

Mechanisms of NF-κB activation

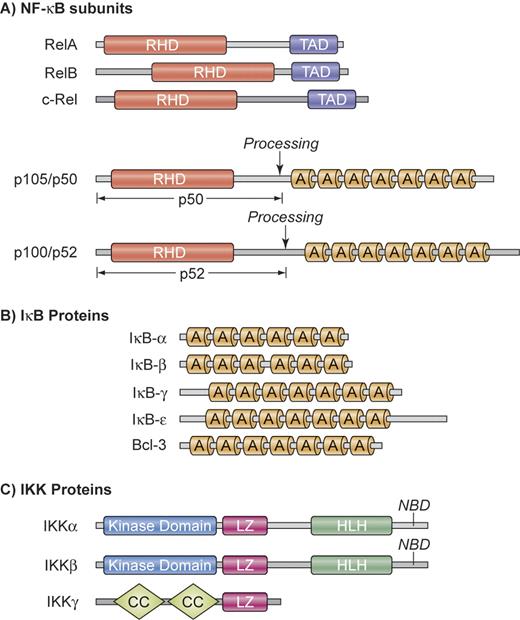

NF-κB is not a single protein, but a small family of inducible transcription factors that operates in virtually all mammalian cells.1 It plays a particular important role in the activation and survival of immune cells.2 The 5 mammalian NF-κB/Rel members are RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p50 and its precursor p105), and NF-κB2 (p52 and its precursor p100) (Figure 1A). These proteins form various homodimers and heterodimers and are kept inactive by cytoplasmic association with inhibitory proteins, which consist of IκBα, IκBβ, IκBϵ, as well as the p105 and p100 precursors of p50 and p52, respectively (Figure 1B). Physiologic activation of NF-κB occurs mainly through either the canonical or the alternative pathway (Figure 2).2 Both pathways are based on inducible phosphorylation of IκB proteins by the multiprotein IκB-kinase (IKK) that contains 2 catalytic subunits, IKKα (IKK1) and IKKβ (IKK2), as well as the regulatory subunit IKKγ (or NEMO for NF-κB essential modifier) (Figure 1C).

Structural organization of NF-κB, IκB, and IKK proteins. (A) NF-κB subunits. NF-κB comprises a group of 5 related transcription factors that share a highly conserved amino-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD), which is responsible for dimerization, nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins. RelA, RelB, and c-Rel additionally possess a carboxy-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) that initiates transcription from NF-κB–binding sites in target genes. The ankyrin repeat (A) containing NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 precursor proteins p105 and p100 can be proteolytically processed to p50 and p52. (B) IκB proteins. The IκB proteins are characterized by the presence of 6 or 7 ankyrin repeats (A) to mediate protein-protein interactions. The ankyrin repeat motif can bind to the nuclear localization sequence of NF-κB proteins and is important for the retention of NF-κB in an inactive state in the cytoplasm. The mammalian IκB family members are IκB-α, IκB-β, IκB-γ, IκB-ϵ, and BCL-3. In addition, NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 precursor proteins p100 and p105 can also function as IκBs. (C) IKK proteins. The IKK complex contains the catalytic kinase subunits IKKα and IKKβ, as well as a regulatory subunit IKKγ (NEMO). IKKα and IKKβ possess a helix-loop-helix region (HLH) and a leucine zipper (LZ), which are responsible for both homodimerization and heterodimerization of IKKα and IKKβ. The catalytic subunits interact through their NEMO-binding domain (NBD) with IKKγ, which contains a coiled coil (CC) domain and a leucine zipper (LZ). Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

Structural organization of NF-κB, IκB, and IKK proteins. (A) NF-κB subunits. NF-κB comprises a group of 5 related transcription factors that share a highly conserved amino-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD), which is responsible for dimerization, nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins. RelA, RelB, and c-Rel additionally possess a carboxy-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) that initiates transcription from NF-κB–binding sites in target genes. The ankyrin repeat (A) containing NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 precursor proteins p105 and p100 can be proteolytically processed to p50 and p52. (B) IκB proteins. The IκB proteins are characterized by the presence of 6 or 7 ankyrin repeats (A) to mediate protein-protein interactions. The ankyrin repeat motif can bind to the nuclear localization sequence of NF-κB proteins and is important for the retention of NF-κB in an inactive state in the cytoplasm. The mammalian IκB family members are IκB-α, IκB-β, IκB-γ, IκB-ϵ, and BCL-3. In addition, NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 precursor proteins p100 and p105 can also function as IκBs. (C) IKK proteins. The IKK complex contains the catalytic kinase subunits IKKα and IKKβ, as well as a regulatory subunit IKKγ (NEMO). IKKα and IKKβ possess a helix-loop-helix region (HLH) and a leucine zipper (LZ), which are responsible for both homodimerization and heterodimerization of IKKα and IKKβ. The catalytic subunits interact through their NEMO-binding domain (NBD) with IKKγ, which contains a coiled coil (CC) domain and a leucine zipper (LZ). Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

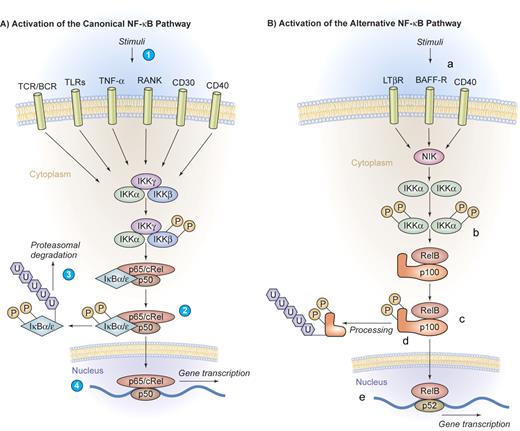

Canonical and alternative pathway of NF-κB activation. (A) Activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway. A series of stimuli activate the canonical pathway of NF-κB activation, including proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, TNF-α, or pathogen-associated molecular patterns that bind to TLRs, the antigen receptors TCR/BCR, or lymphocyte coreceptors such as CD40, CD30, or receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) (1). Activated IKK phosphorylates IκB proteins on 2 conserved serine residues and induces IκB polyubiquitinylation (2), which in turn induces their recognition by the proteasome and causes successive proteolytic degradation (3). Following the IκB degradation, the cytoplasmic NF-κB dimers are released and translocate into the nucleus, where gene transcription is activated (4). (B) Activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway. The alternative pathway of NF-κB activation is engaged by a restricted set of cell-surface receptors that belong to the TNF receptor superfamily, including CD40, the lymphotoxin β receptor, and the BAFF receptor (a). This pathway culminates in the activation of IKKα (b), which can directly phosphorylate NF-κB2/p100 (c), inducing partial proteolysis of p100 to p52 by the proteasome (d). The p52 protein lacks the inhibitory ankyrin repeats and preferentially dimerizes with RelB to translocate into the nucleus (e). Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

Canonical and alternative pathway of NF-κB activation. (A) Activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway. A series of stimuli activate the canonical pathway of NF-κB activation, including proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, TNF-α, or pathogen-associated molecular patterns that bind to TLRs, the antigen receptors TCR/BCR, or lymphocyte coreceptors such as CD40, CD30, or receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) (1). Activated IKK phosphorylates IκB proteins on 2 conserved serine residues and induces IκB polyubiquitinylation (2), which in turn induces their recognition by the proteasome and causes successive proteolytic degradation (3). Following the IκB degradation, the cytoplasmic NF-κB dimers are released and translocate into the nucleus, where gene transcription is activated (4). (B) Activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway. The alternative pathway of NF-κB activation is engaged by a restricted set of cell-surface receptors that belong to the TNF receptor superfamily, including CD40, the lymphotoxin β receptor, and the BAFF receptor (a). This pathway culminates in the activation of IKKα (b), which can directly phosphorylate NF-κB2/p100 (c), inducing partial proteolysis of p100 to p52 by the proteasome (d). The p52 protein lacks the inhibitory ankyrin repeats and preferentially dimerizes with RelB to translocate into the nucleus (e). Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

The canonical pathway of NF-κB activation can be engaged by a large series of stimuli, including proinflammatory cytokines, pathogen-associated molecular patterns that bind to innate immune receptors, T-cell receptor (TCR) and B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, as well as ligation of lymphocyte coreceptors.1-3 Activated IKK phosphorylates IκB proteins, thereby inducing IκB polyubiquitinylation and subsequent proteolytic degradation by the proteasome. Following IκB degradation, NF-κB dimers are released and are then able to translocate into the nucleus, activating gene transcription (Figure 2A).

The alternative pathway of NF-κB activation represents an additional specialized signaling cascade that is particularly important in mature B cells. This pathway is engaged by a restricted set of cell-surface receptors that belong to the TNF receptor superfamily, including CD40, the lymphotoxin β receptor, and BAFF receptor.2 This pathway culminates in the activation of IKKα that directly phosphorylates NF-κB2/p100. This process induces the partial proteolysis of p100 to p52, which preferentially dimerizes with RelB (Figure 2B).

Physiologic functions of NF-κB in lymphocytes

The physiologic functions of the NF-κB subunits and of many upstream regulators have been intensely studied. Particularly, the analyses of mice with genetic mutations in NF-κB signaling components have tremendously advanced our knowledge of this cascade in physiology. These studies revealed essential roles for NF-κB activation in lymphocyte development, activation, proliferation, and survival that have been comprehensively reviewed previously.4 Although each NF-κB subunit has distinct regulatory functions, many of the target genes are common to several NF-κB dimers. The target genes that are relevant for lymphocyte biology can be grouped into several functional classes: positive cell-cycle regulators, antiapoptotic factors, inflammatory and immunoregulatory genes, and negative feedback regulators of NF-κB. The NF-κB–induced cell-cycle regulators that directly drive lymphocyte division include cyclin D1, cyclin D2, c-myc, and c-myb.5-8 NF-κB–induced survival factors include the caspase inhibitors of the cIAP (cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein) family, the BCL2 family members A1 and BCL-XL,9 and c-FLIP (cellular FLICE inhibitor protein).10 NF-κB can additionally trigger lymphocyte proliferation and survival indirectly by inducing immunoregulatory cytokines, lymphokines, or other ligands, including IL-2, IL-6, or CD40L that activate lymphocyte growth receptors in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. Enforced activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway by constitutive active IKKβ in murine B lymphocytes causes accumulation of resting B cells and promotes their proliferation and survival.11

Both constitutive activation of lymphocyte proliferation and/or blockage of cell death are alterations that are required for the development of lymphomas. Consistently, aberrant NF-κB activity has been detected in various lymphoid malignancies. The first reports linking any component of the NF-κB system to oncogenicity in lymphoid organs came from studies with the avian reticuloendotheliosis virus.12 The viral oncogene v-Rel (a homologue of the cellular c-Rel gene) can cause aggressive forms of leukemia and lymphoma in animals. By now, a wide variety of genetic alterations that affect the activity and/or expression of NF-κB/Rel proteins have also been observed in human B- and T-cell malignancies (Table 1).

Deregulation of NF-κB in human lymphoma

Constitutive NF-κB activation is a hallmark of Hodgkin lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is characterized by a low frequency of malignant Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (H/RS) cells in a reactive background of nonmalignant B cells, T cells, eosinophils, histiocytes, and other cells.13 In most cases H/RS cells arise from a germinal center B cell that has lost its BCR surface expression.14 Because normal B cells require BCR expression and signaling for survival,15 the BCR-less H/RS cells must have up-regulated other maintenance pathways to persist.14 Indeed, strong constitutive activation of NF-κB was found to be a characteristic of HL cell lines16 and also of primary H/RS cells.17

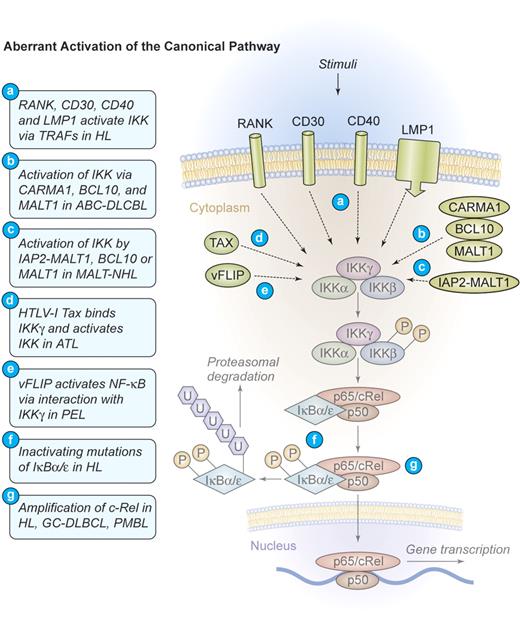

Several distinct mechanisms of aberrant NF-κB activation have been identified in HL. Most frequently found is a constitutive upstream activation of IKK by TNF-α receptor-associated factor (TRAF)–dependent mechanisms.18 TRAFs are signaling molecules that homodimerize and heterodimerize to mediate interactions of signaling proteins such as kinases or ubiquitin-modulating factors to propagate activating signals from cell-surface receptors to IKK.19 Specific for H/RS cells is the self-oligomerization of CD30 receptor molecules that can recruit TRAF2 and TRAF5 to their intracellular tail, subsequently activating IKK (Figure 3). 20,21 CD30 signaling can activate both the canonical and the alternative pathway of NF-κB22 and directly contributes to H/RS cell survival (Figures 3–4). An additional TNF receptor superfamily member that is expressed in H/RS cells is RANK. Cultured H/RS cells were found to coexpress both RANK and its ligand (RANK-L).23 The coexpression of RANK and RANK-L in H/RS cells is likely to result in constitutive RANK signaling, which activates NF-κB through TRAF2, TRAF5, and TRAF6 (Figure 3).24 The third TNF receptor that is frequently expressed in H/RS cells is CD40. In HL, the ligand for CD40 (CD40L, CD154) is present on activated CD4+ cells, surrounding the H/RS cells. These T cells constantly deliver stimuli to the H/RS cells, leading to CD40 oligomerization and TRAF2 as well as TRAF5 recruitment to the intracytoplasmatic tail. Subsequent activation of both canonical and alternative NF-κB signaling takes place (Figures 3–4).25 Additionally, EBV often usurps the CD40 signaling machinery in HL. H/RS cells infected by EBV express the viral latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1),26 a transmembrane protein that possesses an intracellular tail with a high homology to the signaling domain of CD40. Instead of an extracellular ligand-binding region, LMP1 contains 6 hydrophobic transmembrane domains that can strongly self-aggregate, inducing constitutive TRAF2 and TRAF5 oligomerization as well as engagement of the canonical and the alternative NF-κB pathways (Figures 3–4).27

Mechanism of aberrant NF-κB activation through the canonical signaling pathway in human lymphomas. Aberrant activation of the canonical pathway. NF-κB can be aberrantly activated in HL by signals from CD30, CD40, and RANK, which induce the activation of the IKK complex via TRAF proteins. The latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) of EBV engages the intracellular CD40 signaling machinery in HL. CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1 are key upstream mediators of NF-κB activation in ABC-DLBCL. The viral oncoproteins TAX of HTLV-I and vFLIP of HHV-8 are able to bind IKKγ and induce constitutive IKK activation in ATL and PEL, respectively. The fusion protein IAP2-MALT1 or deregulated expression of the proteins MALT1 or BCL10 frequently activates the IKK complex in MALT lymphomas. Deregulated MALT1 expression is also found in selected cases of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and Burkitt lymphoma. Inactivating mutations of IκBα/ϵ, resulting in a decreased inhibitory function and a persistent NF-κB transcriptional activity, have been identified in HL. Amplifications of c-Rel have been recognized in HL, germinal center (GC)–DLBCL, and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL). Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

Mechanism of aberrant NF-κB activation through the canonical signaling pathway in human lymphomas. Aberrant activation of the canonical pathway. NF-κB can be aberrantly activated in HL by signals from CD30, CD40, and RANK, which induce the activation of the IKK complex via TRAF proteins. The latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) of EBV engages the intracellular CD40 signaling machinery in HL. CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1 are key upstream mediators of NF-κB activation in ABC-DLBCL. The viral oncoproteins TAX of HTLV-I and vFLIP of HHV-8 are able to bind IKKγ and induce constitutive IKK activation in ATL and PEL, respectively. The fusion protein IAP2-MALT1 or deregulated expression of the proteins MALT1 or BCL10 frequently activates the IKK complex in MALT lymphomas. Deregulated MALT1 expression is also found in selected cases of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and Burkitt lymphoma. Inactivating mutations of IκBα/ϵ, resulting in a decreased inhibitory function and a persistent NF-κB transcriptional activity, have been identified in HL. Amplifications of c-Rel have been recognized in HL, germinal center (GC)–DLBCL, and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL). Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

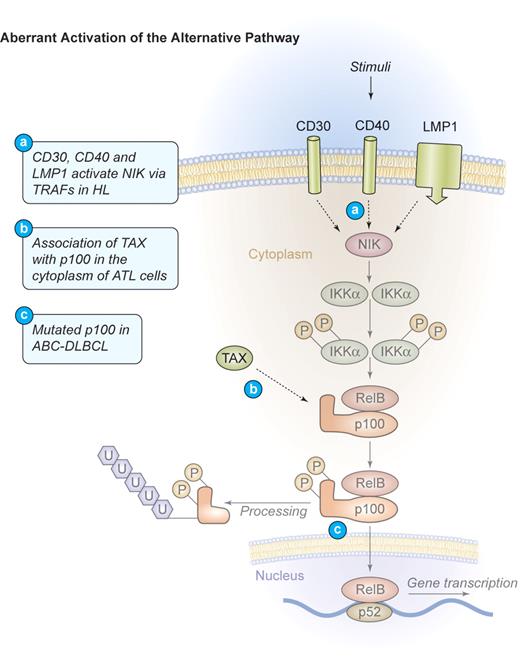

Mechanism of aberrant NF-κB activation through the alternative signaling pathway in human lymphomas. Aberrant activation of the alternative pathway. Signaling through CD30, CD40, and LMP1 also activates the alternative NF-κB pathway via NIK and IKKα in HL. These events lead to the phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of the NF-κB2 precursor protein p100 as well as the translocation of mature p52/RelB dimers into the nucleus. In ATL, TAX can bind to p100 in the cytoplasm and increase its proteolytic processing. Mutations of NF-κB2/p100, leading to a decreased inhibitory p100 function and an increased p52 activity, have been found in cases of ABC-DLBCL. Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

Mechanism of aberrant NF-κB activation through the alternative signaling pathway in human lymphomas. Aberrant activation of the alternative pathway. Signaling through CD30, CD40, and LMP1 also activates the alternative NF-κB pathway via NIK and IKKα in HL. These events lead to the phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of the NF-κB2 precursor protein p100 as well as the translocation of mature p52/RelB dimers into the nucleus. In ATL, TAX can bind to p100 in the cytoplasm and increase its proteolytic processing. Mutations of NF-κB2/p100, leading to a decreased inhibitory p100 function and an increased p52 activity, have been found in cases of ABC-DLBCL. Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

In HL, NF-κB can further be induced by mechanisms that operate downstream of IKK. Inactivating mutations in IKB genes represent one of these alterations. Mutations were detected in the ankyrin repeats of IκBα proteins that lead to its inactivation.18,28 Hemizygous frameshift mutations in IKBE, generating a preterminal stop codon and a hemizygous mutation that affect the 5′-splicing site of intron 1, were additionally found in a HL cell line.29 Interestingly, most IκBα mutations were reported in HL cases that are negative for EBV.30 This could indicate a selective pressure for the acquisition of NF-κB–activating alterations in tumor cases where LMP1 does not signal (Figure 3).

Another common set of genomic alterations that influence NF-κB in H/RS cells directly affects the c-REL locus on chromosome 2p14-15. It is amplified in 50% of all patients, but functional studies of c-REL amplifications in HL are still missing (Figure 3).31-33

The functional consequences of constitutive NF-κB activity in HL were studied with dominant-negative (DN) IκBα mutants.17 These DN-IκBα proteins bind to NF-κB but do not release NF-κB dimers on cellular stimulation and therefore inhibit NF-κB activation. Introduction of DN-IκBα molecules into HL cells resulted in a strong suppression of G1 phase cell-cycle progression. Moreover, these DN-IκBα mutants induce rapid apoptosis of HL cell lines on serum starvation, suggesting that constitutive NF-κB activity promotes proliferation and blocks apoptosis in HL. Further support for this hypothesis came from in vivo experiments. Compared with control HL cells, the xenotransplantation of DN-IκBα transfected HL cells resulted in significantly lower rates of tumor formation in vivo.17 After constitutive NF-κB signaling was found to be a critical prerequisite for H/RS cell survival and proliferation, pharmacologic inhibition of the pathway has been investigated.34 Arsenic-containing compounds are potent inhibitors of NF-κB activation35 by targeting IKKβ. Arsenite treatment can block constitutive IKK activity in H/RS cells,34 leading to a down-regulation of NF-κB DNA binding activity and down-modulation of NF-κB target genes, including TRAF1, c-IAP2, CCR7, and IL-13. In vivo experiments with xenotransplanted H/RS cell lines in nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/Scid) mice demonstrated a substantial reduction of the tumor volume in arsenite-treated animals compared with controls. This reduction was directly associated with decreased NF-κB activity in isolated tumor cells.34 Together, these preclinical studies indicate that strategies to inhibit the NF-κB pathway should be developed as therapies for Hodgkin disease.

Chromosomal translocations of NF-κB signaling molecules provoke antigen-independent MALT lymphoma growth

Marginal zone lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) most commonly arise in the gastric mucosa where they are strongly associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. MALT lymphomas also develop at other sites, often in the context of autoimmune diseases or chronic inflammation.36 Although tumor formation is initially dependent on the presence of antigen,37 more advanced lymphomas grow independent of external stimulation. Several specific genetic alterations were identified in MALT lymphoma. These include the chromosomal translocation t(11;18)(q21;q21), which directly correlates with nonresponsiveness to antibiotic treatment and advanced disease,38 t(14;18)(q32;q21), and t(1;14)(p22;q32). Molecular cloning of the breakpoints identified the oncogenes MALT1 and BCL10.39-41 The translocation t(11;18) leads to the fusion of MALT1 on chromosome 18 to the IAP2 locus on chromosome 11, generating a novel chimeric IAP2-MALT1 protein. The translocations t(14;18) and t(1;14) bring either the full-length MALT1 gene or the BCL10 gene under the control of the immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer on chromosome 14 (Figure 3).

Although involved in independent chromosomal translocations, functional studies demonstrated that MALT1 and BCL10 are able to directly bind to each other and to cooperate in the activation of NF-κB in response to antigen receptor ligation.42-46 In physiologic immune responses, BCL10 is thought to oligomerize MALT1 to initiate a signal transduction cascade that culminates in IKK activation through the ubiquitinylation of IKKγ (NEMO).46 In MALT lymphoma the BCL10 or MALT1 translocations uncouple the BCL10/MALT1 signaling complex from physiologic upstream stimuli to induce constitutive NF-κB activation. The IAP2-MALT1 fusion protein also activates NF-κB autonomously by deregulating IKKγ (NEMO) ubiquitinylation.47 Although wild-type IAP2 can interact with TRAF1 and TRAF2, these 2 adaptors are not required for IAP2-MALT1–induced NF-κB activation.48 In contrast, IAP2-MALT1 can self-oligomerize and mediate ubiquitinylation of IKKγ (NEMO) either directly or via an additional ubiquitin ligase.

Recently, a further independent translocation was detected in MALT lymphoma: t(3;14)(p14.1;q32) brings the forkhead transcription factor FOXP1 under the control of the IgH enhancer on chromosome 14.49 FOXP1 belongs to the FOXP family of proteins that also include FOXP2, a protein involved in speech regulation,50 and FOXP3, the master regulator of regulatory T-cell development and/or function.51 FOXP factors can cooperate with NF-AT or NF-κB,51,52 and FOXP1 specifically controls early B-cell development by regulating recombination-activating gene expression.53 However, whether FOXP1 can cooperate with NF-κB pathways remains to be investigated.

Aberrant NF-κB activation determines poor clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

The most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). On the basis of correlations of microarray gene expression profiling and clinical outcome, it is now possible to classify the majority of DLBCLs into subentities called activated B-cell–like DLBCL (ABC-DLBCL), germinal center–like DLBCL (GC-DLBCL), and an unclassified group of DLBCLs.54-56 Although a 5-year survival rate of 60% can be achieved in GC-DLBCL, patients with ABC-DLBCL and unclassified DLBCL exhibit a much more aggressive disease.54

Analysis of the gene expression signature in the ABC-DLBCL subtype revealed an up-regulation of a large series of classical NF-κB target genes, including BCL-2 family members, c-FLIP, and cyclin D2. Moreover, in cell line models of DLBCL constitutive IKK activity, rapid IκBα degradation, and high nuclear NF-κB DNA binding activity were found in ABC-DLBCL but not in the GC-DLBCL subtype.57 However, the IκBα gene is not commonly mutated in DLBCL.58,59

Introduction of IκBα super-repressor molecules to inhibit NF-κB in distinct DLBCL cell lines resulted in rapid apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest, specifically in ABC-DLBCL cells.57 The GC-DLBCL cells were not affected, indicating that the constitutive NF-κB activity is specifically required for the survival and proliferation of ABC-DLBCL cells.57 Furthermore, using the highly specific small molecule IKKβ inhibitors PS-1145 and MLX105, signal transduction through the IKK complex was blocked in DLBCL cells.60 Both compounds were selectively toxic for ABC-DLBCL cells at nanomolar concentrations but not for GC-DLBCL cells. Cell death was accompanied by a decrease in the expression of NF-κB target genes and an activation of the proapoptotic caspases 3 and 7. Introduction of an estrogen-inducible RelA fusion protein into ABC-DLBCL restored NF-κB activity even in the presence of IKK inhibition, because RelA operates downstream of IKK. The active forms of RelA also stopped apoptosis induction by the kinase inhibitors PS-1145 and MLX105, demonstrating that the NF-κB inhibition is directly responsible for tumor cell death. Using an unbiased subgenomic siRNA library approach, Ngo et al61 recently identified 3 key upstream signaling molecules that mediate constitutive activation of NF-κB in ABC-DLBCL cells. These molecules are CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1, which compose a signaling complex that specifically relays signaling from the BCR to NF-κB (Figure 3).3 Although the mechanisms that activate CARMA1/BCL10/MALT1 signaling in ABC-DLBCL are still unclear, molecular targeting of this signaling cascade should be beneficial for the treatment of ABC-DLBCL.

An additional less common, but distinctive, DLBCL subgroup is the primary mediastinal B-cell lymphomas (PMBLs). PMBL shows also an NF-κB target gene signature, but the clinical outcome of patients with PMBL is much more favorable compared with patients with ABC-DLBCL.62,63 The exact reasons why the patients with PMBL do better is as of yet unclear. However, the gene expression signature of PMBL is more related to Hodgkin disease than to ABC-DLBCL,63 as a wide variety of genes are expressed in both HL and PMBL but not in the other DLBCL subgroups. Although it is not known which upstream pathways deregulate NF-κB in PMBL, the gene expression profile indicates that these pathways might be distinct from the BCR signaling pathway that drives NF-κB in ABC-DLBCL. It can, therefore, be speculated that the difference in clinical outcome of patients with PMBL and patients with ABC-DLBCL might in part be caused by different mechanisms of NF-κB activation.

Some rare, but historically early recognized, NF-κB alterations in DLBCL are direct genomic rearrangements of the NF-KB2 locus on chromosome 10q24,64 including partial or total deletions of the 3′-end of the NFKB2 gene. These mutations result in an increased NF-κB2 mRNA expression and a deletion of the carboxy-terminal ankyrin repeats of the NF-κB2 protein, giving rise to a constitutive transcriptional activator with oncogenic potential (Figures 3–4).65 Furthermore, amplifications of the NF-κB subunit c-Rel were detected in DLBCL but predominantly in GC-DLBCL (Figure 3).56 Because c-Rel amplifications do not correlate with global NF-κB target gene expression, their pathogenetic relevance in GC-DLBCL needs to be further evaluated.31,66,67

Viral oncoproteins activate NF-κB in primary effusion lymphoma and adult human T-cell lymphoma/leukemia

In addition to EBV, there are 2 other human lymphomagenic viruses known that carry NF-κB–activating oncoproteins. These are the Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also called human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and the human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-1), which play a critical role in primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (ATL), respectively.

PEL is a rare high-grade B-cell malignancy associated with KSHV infection.68 Often the PEL cells are also coinfected with EBV, but, once a lymphoma develops in which both EBV and KSHV are present, KSHV expresses a set of latent genes, whereas EBV latent gene expression is fairly restricted.69 KSHV contains a homologue of the cellular FLIP protein called vFLIP that has the ability to activate the NF-κB pathway in a variety of overexpression systems (Figure 3).70,71 When experimentally transfected into murine B-cell lymphoma cells, it facilitates their tumor growth in mice.72 Biochemically, vFLIP binds to the IKK complex to induce constitutive kinase activation.73 Consequently, all PEL cell lines tested have high levels of nuclear NF-κB activity.74 Treatment of PEL cells with the IKK inhibitor Bay 11-7082 abrogates the NF-κB DNA binding activity and again results in a down-regulation of the NF-κB–dependent cytokine IL-6 and in apoptosis. In addition, direct targeting of vFLIP with siRNA approaches also induced cell death in KSHV-infected PEL cells.74 Together, these studies support the idea that vFLIP-mediated NF-κB activation is necessary for the survival of PEL lymphoma cells and that this pathway represents a target for a molecular therapy of this disease.

The adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (ATL) is an aggressive malignant disease of T cells that is caused by the endemic human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-1).75 HTLV-1–mediated transformation of T lymphocytes is dependent on the 40-kDa Tax phospho-oncoprotein.76,77 Tax is sufficient to immortalize primary human T cells78 and is able to transform rodent fibroblasts, inducing tumors in nude mice.79 When expressed as a transgene, it provokes leukemia and lymphoma development in animals.80,81 Tax can directly bind to IKKγ and activate the IKK-complex (Figure 3),82 leading to increased phosphorylation of both IκBα and IκBβ and a persistent activation of the classical NF-κB pathway.83,84 Tax can also associate with the inhibitory p100 precursor of NF-κB2, abrogating p100 inhibition, and thereby activating the alternative NF-κB pathway (Figure 4).85,86 Consistently, human ATL cells exhibit a constitutive activation of NF-κB87 and an up-regulation of NF-κB–dependent proteins, including IL-2, the IL-2 receptor α-chain, BCL-XL, D-type cyclins, and c-MYC.88,89 Chemical inhibition of NF-κB signaling was investigated in primary ATL cells90 using the IKK-inhibitor Bay 11-7082. Rapid and efficient reduction of NF-κB DNA binding activity and down-regulation of its targets BCL-XL, cyclin D1, and cyclin D2 in HTLV-I–infected cells was observed. This resulted in a profound apoptosis induction and the killing of freshly isolated primary leukemic cells from patients with ATL, confirming the NF-κB pathway as a potential therapeutic target in ATL.

Conclusions and perspectives

The central importance of the NF-κB pathway for physiologic lymphocyte proliferation and survival has been known for several years. Now, it is realized that its aberration is causally connected to lymphoma development. Pathogenetic NF-κB activation pathways have been specifically identified in HL, ABC-DLBCL, MALT lymphoma, PEL, and ATL. A further lymphoid malignancy, which is at least in part dependent on aberrant NF-κB activity, is multiple myeloma (MM). In addition to MM cell intrinsic-transforming events, which do not necessarily involve NF-κB, MM cells require close contact to bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) in their microenvironment for proliferation and expansion.91 The BMSCs produce IL-6 as a major growth and survival factor for the MM cells in an NF-κB–dependent fashion. Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor that blocks IκBα degradation, increases IκB levels in cells, and shifts NF-κB from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. In vitro experiments show that bortezomib directly down-regulates IL-6 production in BMSCs,92 causing a block in proliferation and death of the tumor cells. Landmark clinical trials have shown that bortezomib is highly effective as a single agent or in combination with dexamethasone in patients with MM with manageable side effects.93 Although bortezomib is not specific for NF-κB but additionally affects other cellular signaling pathways that involve the proteasome, the NF-κB inhibition by bortezomib clearly contributes to its efficiency.91 On the basis of the promising clinical results of bortezomib in MM, several clinical trials are currently ongoing that investigate bortezomib in a spectrum of other tumors, particularly lymphomas including those with aberrant NF-κB signaling.94,95

In conclusion, accumulating experimental and preclinical data validates the NF-κB pathway as a promising therapeutic target in lymphomas. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling could potentially be effective as single agents in lymphomas that solely depend on NF-κB for survival. However, blocking NF-κB could also be useful in combination with radiotherapy or chemotherapy, especially because these DNA-damaging strategies secondarily induce NF-κB activation96 and because NF-κB activity in lymphoma blocks intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways that are engaged by and are required for conventional therapies.53 However, because NF-κB has also important nonredundant functions in normal cell physiology, a general and complete inhibition of NF-κB might not be optimal. One attractive lymphocyte-specific pathway for therapeutic targeting is the CARMA1/BCL10/MALT1 signaling cascade. The challenge for the future is to develop intelligent strategies for NF-κB upstream inhibition that target pathways, which are selectively relevant in lymphocytes and in lymphomas.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jürgen Ruland, III. Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, Ismaninger Str. 22, 81675 Munich, Germany; e-mail: jruland@lrz.tum.de.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Peschel, Ulrich Keller, Ellis Muggleton, and Konstanze Pechloff for scientific discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Max-Eder-Program Grant from Deutsche Krebshilfe and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB grants).