In comparison with standard myeloablative conditioning regimens in preparation for allografting in multiple myeloma, reduced-intensity conditioning treatments decreased transplantation-related mortality at a cost of higher relapse rates and shorter progression-free survival, without extending overall survival.

Over the last few years, there has been a progressive shift from myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens to reduced-intensity, or nonmyeloablative, conditioning (RIC) treatments in preparation for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. This change was justified by the need to decrease transplantation-related mortality below the 20% to 30% range seen with MAC regimens1 and to extend the age range of allograft recipients. Surprisingly, no study providing evidence of the superiority of RIC over MAC regimens has been reported to date in support of the widespread use of reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation.

The paper by Crawley and colleagues published in this issue of Blood tries to shed light on this poorly investigated issue. For this purpose, the authors retrospectively analyzed the outcomes of 516 myeloma patients who received allografts from 1998 to 2002 and were reported to the European Blood and Marrow Transplant registry. The overall transplantation-related mortality at 2 years for the 320 patients receiving RIC regimens was 24%, a value lower than that of 196 patients prepared with myeloablative treatments (37%). However, reduced mortality associated with nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation was at a cost of significantly lower complete remission rates (33.6% versus 53.4% for MAC regimens) and a double risk of relapse compared with that observed with myeloablative allografts (54% versus 27% at 3 years, respectively; hazard risk: 1.0 versus 0.51, respectively) (see figure). As a result, the 3-year progression-free survival for patients receiving RIC regimens was only 18.9%, as opposed to 34.5% for myeloablative-treated patients. The corresponding 3-year overall survival probabilities were 38.1% and 50.8%, respectively (see figure).

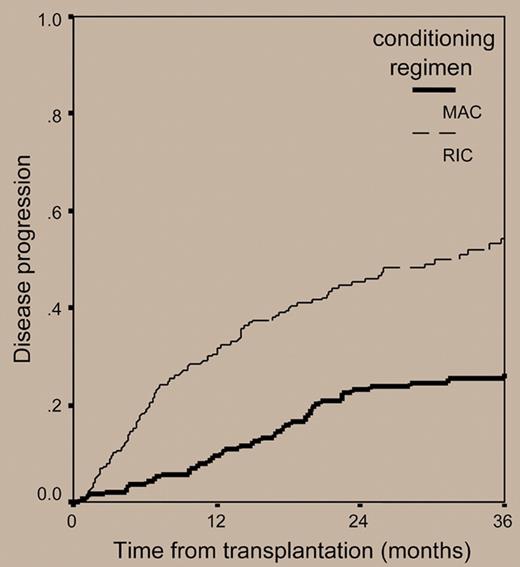

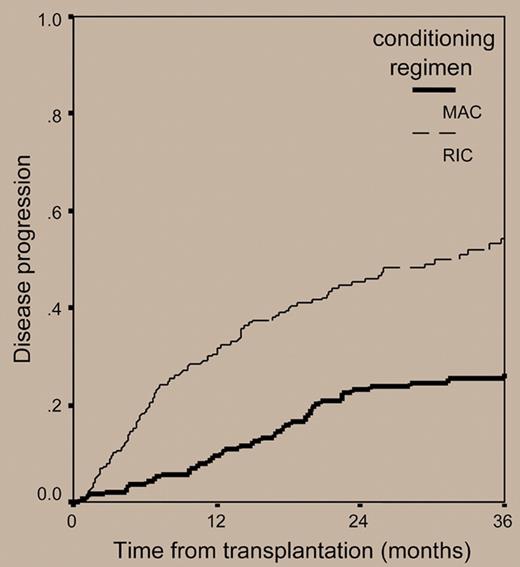

Cumulative incidence of disease relapse or progression in 516 patients with myeloma who underwent transplantation with reduced-intensity or myeloablative conditioning regimens.

Cumulative incidence of disease relapse or progression in 516 patients with myeloma who underwent transplantation with reduced-intensity or myeloablative conditioning regimens.

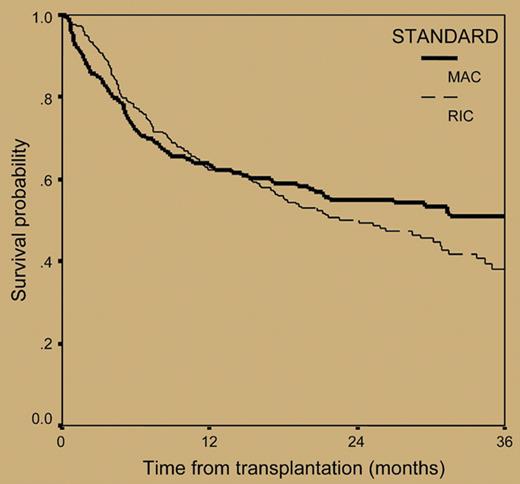

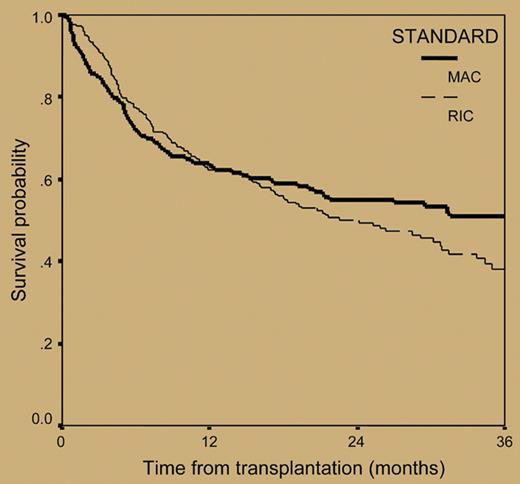

Overall survival from transplantation in 516 patients with myeloma who underwent transplantation with reduced-intensity or myeloablative conditioning regimens. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 3588.

Overall survival from transplantation in 516 patients with myeloma who underwent transplantation with reduced-intensity or myeloablative conditioning regimens. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 3588.

Although these data might suggest that harnessing the graft-versus-myeloma effect in the context of RIC regimens does not substitute marked cytoreduction delivered with myeloablative treatments, results should be cautiously interpreted due to major differences between the 2 groups of patients analyzed. In particular, in comparison with patients in the myeloablative-treated group, patients who received RIC regimens had a higher frequency of progressive myeloma, underwent transplantation later in the course of the disease, and were treated more frequently with antithymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab; all these variables were independent risk factors for a poorer outcome in multivariate analyses.

Despite these caveats, several limitations of reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation have been recognized, particularly in heavily pretreated patients with advanced refractory disease2 and/or chromosome 13 alterations.3 On the contrary, a consensus has emerged that upfront tandem autologous-allogeneic stem cell transplantation provides better outcomes,4 although it was not superior to double autologous transplantation in high-risk patients with chromosome 13 alterations and elevated serum beta 2 microglobulin levels.5

In conclusion, in multiple myeloma, allogeneic stem cell transplantation prepared with RIC regimens still remains an investigational treatment option that should be recommended only in the context of clinical trials. In these studies, application of cytogenetics and molecular genetics should aid a more accurate identification of those patients who are more likely to benefit, or not, from nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation. Due to the need to better balance immunosuppression with cytoreduction, clinical trials exploiting alternative immunosuppressive strategies to assure donor engraftment while preserving a graft-versus-myeloma effect seem appropriate. Concurrently, major experimental challenges lie ahead to increase the therapeutic efficacy of allografts by investigating the role of novel agents as part of the conditioning regimens and/or as posttransplantation maintenance therapies.6 Finally, outside clinical trials or in particular settings, such as that of high-risk patients who carry cytogenetic abnormalities for whom double autologous transplantation is unlikely to result in beneficial outcomes, standard myeloablative allografting still has a role.

The author declares no competing financial interests. ▪