Abstract

Steroids have been shown to inhibit the function of fresh or IL-2–activated natural killer (NK) cells. Since IL-15 plays a key role in NK-cell development and function, we comparatively analyzed the effects of methylprednisolone on IL-2– or IL-15–cultured NK cells. Methylprednisolone inhibited the surface expression of the major activating receptors NKp30 and NKp44 in both conditions, whereas NK-cell proliferation and survival were sharply impaired only in IL-2–cultured NK cells. Accordingly, methylprednisolone inhibited Tyr phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in IL-2–cultured NK cells but only marginally in IL-15–cultured NK cells, whereas JAK3 was inhibited under both conditions. Also, the NK cytotoxicity was similarly impaired in IL-2– or IL-15–cultured NK cells. This effect strictly correlated with the inhibition of ERK1/2 Tyr phosphorylation, perforin release, and cytotoxicity in a redirected killing assay against the FcRγ+ P815 target cells upon cross-linking of NKp46, NKG2D, or 2B4 receptors. In contrast, in the case of CD16, inhibition of ERK1/2 Tyr phosphorylation, perforin release, and cytotoxicity were not impaired. Our study suggests a different ability of IL-15–cultured NK cells to survive to steroid treatment, thus offering interesting clues for a correct NK-cell cytokine conditioning in adoptive immunotherapy.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells represent a lymphocyte population capable of recognizing and lysing tumor cells and virus-infected cells in the absence of previous sensitization.1,2 NK-cell function is regulated by a balance between activating and inhibitory signals. Upon specific recognition of HLA class I molecules, the HLA class I–specific inhibitory receptors suppress NK-cell cytolytic activity, whereas target-cell lysis will require a partial or complete down-regulation of HLA class I molecules.3–7

Several structurally different activating receptors are involved in NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity. The CD16 receptor, expressed on the majority of peripheral-blood NK cells, mediates antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC) against IgG-coated target cells. CD16 associates with CD3ζ and FcϵRγ, which carry cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs).8 NK-mediated lysis of tumor cells or virus-infected cells is mainly mediated by NKp46, NKp30, and NKp44 (collectively referred to as natural cytotoxicity receptors [NCRs]) and by NKG2D.5,9–11 NKp46 and NKp30 are present on both resting and activated NK cells, whereas NKp44 is expressed only upon NK-cell activation. NKp30 and NKp46 deliver intracellular signals, thanks to their association with CD3ζ or CD3ζ plus FcϵRγ, respectively, whereas NKp44 associates with the KARAP/DAP12 molecules.12 Other activating receptors include DNAM-1, 2B4, NTBA, and NKp80. Notably, 2B4, NTBA, and NKp80 are considered coreceptors, as they can significantly increase the NK-cell cytotoxicity against some cellular targets when they are coengaged with NCRs or NKG2D.13–17

It is evident that the surface expression of activating receptors is crucial for the NK-mediated killing of various target cells. Therefore, it appeared conceivable that immunosuppressive drugs such as glucocorticoids (GCs) could impair the NK-cell function by affecting the surface expression and/or the function of activating NK receptors. In this context, we have recently shown that pediatric patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) display a profound down-regulation of most activating NK receptors and coreceptors and an impaired cytolytic activity. This effect appeared to be related to the administration of methylprednisolone (MePDN) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). Indeed, in vitro analysis of NK cells from healthy donors confirmed that MePDN could induce both down-regulation of the NKp30 and NKG2D activating NK receptors and a sharp impairment of NK-cell function. Moreover, in spite of its unaltered surface expression, NKp46 failed to efficiently transduce triggering signals.18

In this context, however, it should be stressed that NK-cell cytotoxicity is a complex process that requires adhesion to target cells, synapse formation, signal transduction leading to granule polarization, and exocytosis. Accordingly, it is conceivable that MePDN might also interfere with different steps of this process.

In previous studies, GCs have been shown to inhibit different T-cell functional activities (including proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production) mostly by interfering with the IL-2–induced JAK-STAT signaling pathway and with the transactivation of other transcription factors such as NF-kB and activated protein-1 (AP-1).19–23 These effects appear to be mainly mediated by GC-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) and the MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1). Remarkably, their expression is positively regulated by GCs. Both proteins have been shown to interfere with NF-kB– and AP-1–mediated transcription and to inhibit both MAPK kinase activity and ERK-mediated signaling.19,24–27 It is of note that ERK activation is required for lymphocyte proliferation and is involved in lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity through the induction of granule exocytosis.28–30

In order to extend our previous finding that MePDN exerts an inhibitory effect on NK-cell function, we analyzed the effect of MePDN treatment on NK cells cultured in the presence not only of IL-2 but also of IL-15, a cytokine that plays a major role in the NK-cell development in vivo as well as in NK-cell activation and proliferation.31–34 We show that IL-2–cultured NK cells display a higher susceptibility to apoptotic cell death and to inhibition of cell proliferation compared with NK cells cultured in IL-15. The effect of MePDN on Tyr phosphorylation of STAT1, 3, and 5 and JAK3 as well as of ERK1/2 was also investigated both in NK cells activated by IL-2 or IL-15 and following cross-linking of their activating NK receptors. Finally, we analyzed the effect of MePDN on ERK1/2 phosphorylation and granule exocytosis, a crucial step in NK-cell cytotoxicity and target-cell lysis.

Materials and methods

Approval was obtained for these studies from the institutional review boards of the Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IST) and the Ospedale San Martino, Genova, and the G. Gaslini Institute. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell cultures

Peripheral-blood mononucleated cells (PBMCs) were collected from peripheral blood of healthy donors and isolated by centrifugation on density gradient (Lympholyte; Cedarlane Lab, Hornby, ON, Canada) as previously described.35 NK cells were purified from whole blood by negative selection with a Rosette-Sep NK separation kit (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). NK cells were plated in 96-well round-bottom plates (Falcon/Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at the concentration of 3 × 105 cells/well. They were cultured for different time intervals in RPMI 1640 (BioWhittaker, Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium) plus penicillin-streptomycin-neomycin and L-glutamine 1% mixture (BioWhittaker) in the presence of IL-2 at 100 U/mL (Proleukin, kindly provided by Chiron-ITALIA, Milano, Italy) or IL-15 at 20 ng/mL corresponding to 40 U/mL (Peprotech, London, United Kingdom) alone or in combination with different concentrations of MePDN (1, 0.5, 0.1, 0.01 μg/mL, corresponding to 2 × 10−6 M, 1 × 10−6 M, 2 × 10−7 M, and 2 × 10−8 M, respectively; Urbason, Aventis-Pharma, Gruppo Lepetit, Anagni, Italy). In order to assess NK-cell proliferation and survival, a dose-response curve was performed in NK cells cultured in the presence of different concentrations of IL-2 (200 U/mL, 100 U/mL, 20 U/mL) or IL-15 (50 ng/mL, 25 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, corresponding to 100 U/mL, 50 U/mL, and 10 U/mL, respectively) in the presence or absence of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL).

mAbs and cytofluorimetric analysis

The following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were produced in our laboratory: JT3a (anti-CD3; IgG2a), KD1 (anti-CD16; IgG2a), and c218 (anti-CD56; IgG1). The following mAbs were kindly provided by D. Pende or A. Moretta: GPR165 (anti-CD56; IgG2a), 7A6 (anti-NKp30; IgG1), (anti-NKG2D; IgG1), BAB 281 (anti-NKp46; IgG1), PP35 (anti-2B4; IgG1), and F22 (anti-DNAM-1; IgG1).5,13 Cytofluorimetric analyses were performed on resting or activated NK cells as previously described.13 For intracytoplasmic immunofluorescence analysis, 5 × 105 NK cells were fixed upon incubation for 5 minutes with 1 mL of 4% formaldehyde solution and washed; cell permeability was induced by cell treatment with 20 μL of 1% NP40 solution. Cells were then washed and stained with appropriate labeled mAbs. Cytofluorimetric analyses were also used for detection of cell death and apoptosis. Annexin V–FITC (MBL Medical and Biological Laboratories, Naka-ku, Nagaya, Japan) was used to evaluate the number of cells undergoing apoptosis. Briefly, aliquots of cells in different culture conditions were collected, washed in PBS, resuspended in the binding buffer (10 mM Hepes/NaOH [pH 7.4]/140 mM NaCl/2.5 mM CaCl2), and mixed with 1 μL of annexin V–FITC/105 cells and 1 μL of propidium iodide (PI) at a final concentration of 2 μg/mL. After 5 minutes of incubation in the dark at room temperature, cells were analyzed by using flow cytometry. The criteria for cell death measured by flow cytometry were based on the following parameters: changes in light-scattering properties (forward side scattering and side scattering) of dead cells because of cell shrinkage and increased granularity. Samples were analyzed by Cell Quest program (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Data are expressed as logarithmic values of fluorescence intensity.

Cytolytic assay and detection of perforin granule release

NK-cell cytotoxicity was analyzed in a 4-hour 51Cr-release assay against the 721.221 B-EBV human cell line, the melanoma FO1 human cell line, and the FcγR+ P815 mastocytoma murine cell line, as previously described.36 All experiments were performed in duplicates and data are expressed as percentage of lysis of target cells. Analysis and quantification of granule release was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay. IL-2– or IL-15–stimulated NK cells were cultured for 4 days in the presence or absence of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL). Cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in 10% FCS + RPMI medium. They were then stimulated by cross-linking of various NK receptors with appropriate mAbs. After overnight incubation at 37°C, supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA assay specific for in vitro quantitative determination of perforin (Perforin-ELISA kit; Diaclone Research, Besancon Cedex, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis (WB)

NK receptor cross-linking.

After 4 days of culture in IL-2 100 U/mL or IL-15 20 ng/mL, with or without MePDN 0.5 μg/mL, cells were starved, to reduce basal phosphorylation, for 4 hours at 37°C in serum-free medium. Collected viable cells were labeled with the appropriate mAbs for 30 minutes at 4°C. After washing, cells were stimulated with AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti–mouse IgG (GAM, H+L; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) 10 μg/mL for 5 minutes at 37°C. Reaction was stopped with ice-cold PBS and cells were centrifuged. Cell pellets were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (20% SDS; 50% Tris HCl 1 M, pH 6.8; 5% β-mercaptoetanolo; 25% glycerol; bromophenol blue). Samples were stored at 80°C.

CD132, STATs, JAK3, and ERK phosphorylation analysis.

After overnight culture in IL-2 100 U/mL or IL-15 20 ng/mL, with or without MePDN at different concentrations (1 μg/mL, 0.5 μg/mL, 0.1 μg/mL, 0.01 μg/mL), cells were centrifugated and cell pellets were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (see “NK receptor cross-linking”). Samples were stored at 80°C. Rabbit polyclonal Ab against CD132 (62 kDa) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit Abs against human phospho-STAT1 (p-STAT1; Tyr 701), STAT1 (84/91 kDa), and p-STAT3 (Tyr 705; 79/86 kDa) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); murine mAb against STAT3 (92 kDa) and rabbit polyclonal Ab against p-JAK3 (Tyr 980) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Murine mAbs against human p-STAT5 (Tyr 694; 92 kDa) and STAT5 (92 kDa) were purchased from BD Bioscience Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). Murine mAb against p-ERK1/2 (Tyr 204) and goat Ab ERK 2 (C-14) sc-154-G against ERK2 p42 (42 kDa) and ERK1 p44 (44 kDa) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary HRP-conjugated goat antimouse, goat antirabbit, and rabbit antigoat antibodies and murine mAb against α-tubulin (54 kDa) were also purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Lysates were analyzed on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the proteins were transferred to Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) overnight, and WB was performed as previously described37 followed by detection using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in experiments of NK-cell survival, proliferation, and NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity. Nonparametric paired t test parallel analysis (Wilcoxon signed rank test) was used to compare the percentages of NK-cell annexin-V binding or of NK-cell proliferation in the presence of MePDN and different concentrations of IL-2 or IL-15 cytokine (200 U/mL IL-2 vs 50 ng/mL IL-15; 100 U/mL IL-2 vs 25 ng/mL IL-15; and 20 U/mL IL-2 vs 5 ng/mL IL-15) versus controls in which NK cells were cultured with cytokines alone. Parallel analysis was performed to compare the levels of each NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity in the presence of MePDN and IL-2 or IL-15. In order to evaluate our data, a nonparametric t test (Mann-Whitney) was used. Differences were considered significant when P values were less than .05.

Results

Inhibitory effect of MePDN on the surface expression of NKp30 and NKp44 and proliferation in response to IL-2 or IL-15

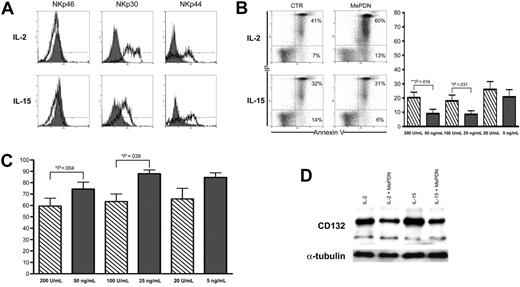

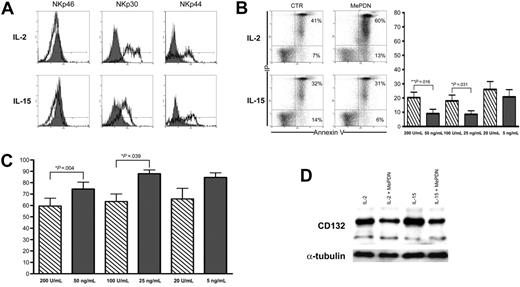

We had previously shown that MePDN induces a partial inhibition of human NK-cell proliferation and inhibits the surface expression of NKp30 and NKp44 activating receptors. This was observed both in vivo, in pediatric patients undergoing steroid therapy to treat GvHD who also received HSC transplants, and in vitro, upon NK-cell culture in IL-2.18 Since it is generally accepted that IL-15 plays a key role in NK-cell development and activation, we investigated whether IL-15–cultured NK cells were susceptible to steroid-mediated inhibition. NK cells from healthy donors were cultured with IL-2 or IL-15 in the presence or absence of MePDN at different concentrations, ranging from 1 to 0.01 μg/mL (ie, between 2 × 10−6 M and 2 × 10−8 M). After 5 days of culture, cytofluorimetric analysis revealed that in the presence of MePDN, NK cells that had been cultured either in IL-2 or in IL-15 displayed a sharp down-regulation of NKp30 and failed to express NKp44. On the other hand, surface expression of NKp46 (Figure 1A), NKG2D, and 2B4 (not shown) was not affected. Figure 1A shows a representative experiment of 15 performed. Although not shown, the inhibitory effect of MePDN was clearly dose dependent.

MePDN-mediated effects on NKp30 and NKp44 surface expression and on NK-cell survival and proliferation in the presence of IL-2 or IL-15. (A) NK cells were cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) either with MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL (gray profiles) or without MePDN (empty profiles). Cytofluorimetric analysis revealed that MePDN selectively inhibited NKp30 and NKp44 surface expression. This experiment is representative of 15 independent experiments performed using different donors. (B) In order to analyze whether MePDN could affect NK-cell survival, we performed, at different time intervals (day 3 and day 5), cytofluorimetric analysis of annexin-V surface expression on NK cells cultured in the presence of different concentrations of IL-2 (200 U/mL, 100 U/mL, 20 U/mL) or IL-15 (50 ng/mL, 25 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, corresponding to 100 U/mL, 50 U/mL, and 10 U/mL, respectively). (left) An experiment representative of 11 independent analyses (performed at day 3) is shown. (right) Analysis of annexin V–binding NK cells cultured with MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) in the presence of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) versus control NK cells in IL-2 or IL-15 alone. Data are expressed as the mean percentage (± SEM) of 7 independent experiments. Statistical significance was checked by nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. (C) NK cells cultured for 5 days in different concentrations of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) in the presence or absence of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) were counted with trypan blue to exclude dead cells. Results are expressed as the mean percentage (± SEM) of NK-cell proliferation in response to IL-2 or IL-15 with MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) versus control NK cells (ie, without MePDN), evaluated in 11 independent experiments. Bars indicate standard error. Statistical significance was checked by a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. (D) NK cells were cultured for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. Cell extracts were analyzed by WB in order to assess the content of CD132. The expression of α-tubulin was analyzed to assess comparable amounts of protein. This experiment is representative of 3 performed.

MePDN-mediated effects on NKp30 and NKp44 surface expression and on NK-cell survival and proliferation in the presence of IL-2 or IL-15. (A) NK cells were cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) either with MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL (gray profiles) or without MePDN (empty profiles). Cytofluorimetric analysis revealed that MePDN selectively inhibited NKp30 and NKp44 surface expression. This experiment is representative of 15 independent experiments performed using different donors. (B) In order to analyze whether MePDN could affect NK-cell survival, we performed, at different time intervals (day 3 and day 5), cytofluorimetric analysis of annexin-V surface expression on NK cells cultured in the presence of different concentrations of IL-2 (200 U/mL, 100 U/mL, 20 U/mL) or IL-15 (50 ng/mL, 25 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, corresponding to 100 U/mL, 50 U/mL, and 10 U/mL, respectively). (left) An experiment representative of 11 independent analyses (performed at day 3) is shown. (right) Analysis of annexin V–binding NK cells cultured with MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) in the presence of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) versus control NK cells in IL-2 or IL-15 alone. Data are expressed as the mean percentage (± SEM) of 7 independent experiments. Statistical significance was checked by nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. (C) NK cells cultured for 5 days in different concentrations of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) in the presence or absence of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) were counted with trypan blue to exclude dead cells. Results are expressed as the mean percentage (± SEM) of NK-cell proliferation in response to IL-2 or IL-15 with MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) versus control NK cells (ie, without MePDN), evaluated in 11 independent experiments. Bars indicate standard error. Statistical significance was checked by a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. (D) NK cells were cultured for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. Cell extracts were analyzed by WB in order to assess the content of CD132. The expression of α-tubulin was analyzed to assess comparable amounts of protein. This experiment is representative of 3 performed.

Next we performed a parallel assessment of both cell survival and proliferation in MePDN-treated NK cells cultured in the presence of different concentrations of either IL-2 or IL-15 (see “Cell cultures” under “Materials and methods”). Marked differences existed between the 2 cell-culture conditions. In these experiments, the MePDN-induced apoptotic cell death was assessed at different time intervals (at days 3 and 5 of culture). Figure 1B (left) shows the cytofluorimetric analysis of the surface expression of annexin V in IL-2– or IL-15–cultured NK cells in the presence of MePDN. The data shown are representative of 11 experiments performed using different donors. It is evident that IL-15, but not IL-2, protected NK cells from corticosteroid-induced apoptosis (Figure 1B left). Differences between NK cells cultured either with IL-2 at 200 U/mL versus IL-15 at 50 ng/mL or with IL-2 at 100 U/mL versus IL-15 at 25 ng/mL were statistically significant (P = .016 and P = .031, respectively). Data are expressed as mean percentage (±SEM) of annexin-V binding in MePDN-treated versus control NK cells (Figure 1B right). These results were consistent with those of cell proliferation measured at day 5 of culture. Figure 1C represents the percentage of cell proliferation detected in NK cells cultured with MePDN (0.5 μg/mL) versus control NK cells cultured with different concentrations of IL-2 or IL-15 alone. The results are expressed as the mean percentage (±SEM) of 7 independent experiments using different donors. Parallel analysis of NK cells cultured in the presence of either IL-2 at 200 U/mL versus IL-15 at 50 ng/mL or IL-2 at 100 U/mL versus IL-15 at 25 ng/mL revealed significant differences in the inhibitory effect of MePDN on cell proliferation (P = .004 and P = .039, respectively).

In view of these results, we next investigated whether the surface expression of α, β (CD122), and γ (CD132) chains of the IL-2 and IL-15 receptor complexes was affected by MePDN treatment. As shown in Figure 1D, WB revealed that in spite of a marked difference in NK-cell proliferation, the protein content of CD132 was markedly reduced in cells cultured with MePDN both in IL-2 and IL-15; on the other hand, the surface expression of the other receptor subunits was only marginally affected (not shown).

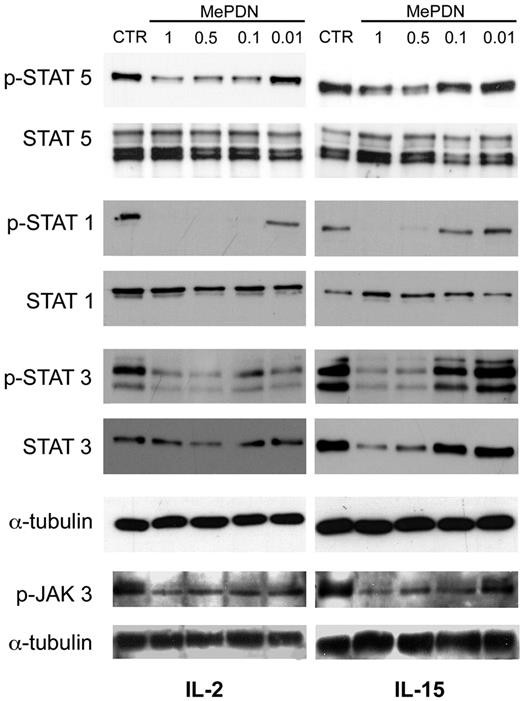

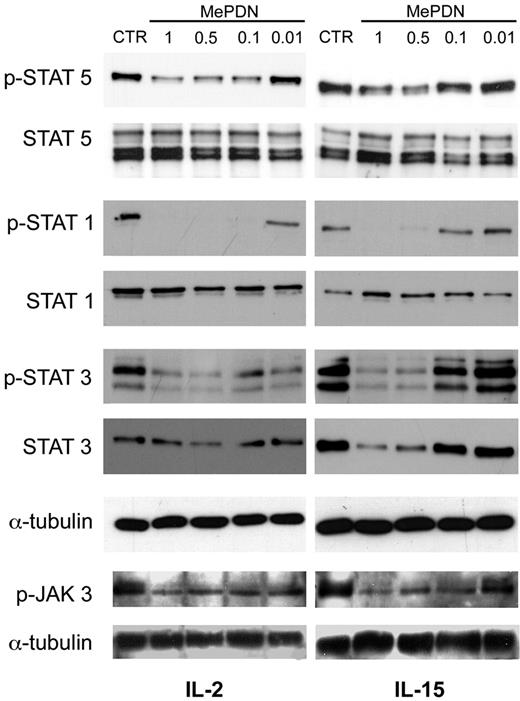

MePDN interferes with the IL-2/IL-15 signaling pathway by inhibiting STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and JAK3 Tyr phosphorylation

We next investigated whether the IL-2 and IL-15 signal transduction pathways were differently affected by corticosteroid treatment. Since CD122 and CD132 subunits are common for IL-2 and IL-15 receptor complexes, the signal transduction pathways involved are shared as well.38 CD132 is known to bind JAK3, which activates STAT5, whereas CD122 displays tyrosine sites that bind JAK1, which, in turn, activates STAT3.38,39 Recent data revealed that STAT1 also becomes phosphorylated upon IL-2 receptor cross-linking.40 Thus, we analyzed Tyr phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and JAK3 in NK cells cultured in IL-2 or IL-15 in the presence or absence of MePDN. To this end, freshly isolated NK cells were cultured overnight with IL-2 or IL-15 in the presence or absence of different steroid concentrations. Cells were harvested and cell pellets analyzed in Western blot. Figure 2 shows a representative experiment of 6 performed. In IL-2–cultured NK cells, STAT5, STAT1, and STAT3 Tyr phosphorylation was sharply inhibited by MePDN up to the steroid concentration of 0.01 μg/mL (Figure 2 left). In contrast, in the presence of IL-15 (Figure 2 right), inhibition of STAT phosphorylation only occurred at the highest steroid concentrations (1 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL). Analysis of JAK3 revealed that MePDN treatment induced similar levels of inhibition of Tyr phosphorylation both in the presence of IL-2 and in the presence of IL-15. It is of note that kinetic studies revealed that inhibition of STAT phosphorylation started 4 hours after the exposure of cells to MePDN and was still observed after 24 hours (data not shown). These data support the notion of a long-lasting effect that is also suggested by the finding of a reduced STAT3 protein content.

MePDN differently affects the IL-2– or IL-15–induced Tyr phosphorylation of STAT1, 3, and 5 and JAK3 molecules. Purified NK cells were cultured overnight with IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence or absence (control = CTR) of different MePDN concentrations from 1 to 0.01 μg/mL (MePDN 1, MePDN 0.5, MePDN 0.1, MePDN 0.01). Total-cell lysates were analyzed by WB using antihuman antibodies against p-JAK3, p-STAT5, p-STAT1, and p-STAT3. Each membrane was probed again with antibodies recognizing the native proteins in order to assess comparable amounts of proteins, with the exception of JAK3. The α-tubulin derived from STAT3 membrane is shown as representative control. For p-JAK3 membranes, only the expression of α-tubulin was analyzed to assess comparable amounts of protein. These data are representative of 7 different experiments.

MePDN differently affects the IL-2– or IL-15–induced Tyr phosphorylation of STAT1, 3, and 5 and JAK3 molecules. Purified NK cells were cultured overnight with IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence or absence (control = CTR) of different MePDN concentrations from 1 to 0.01 μg/mL (MePDN 1, MePDN 0.5, MePDN 0.1, MePDN 0.01). Total-cell lysates were analyzed by WB using antihuman antibodies against p-JAK3, p-STAT5, p-STAT1, and p-STAT3. Each membrane was probed again with antibodies recognizing the native proteins in order to assess comparable amounts of proteins, with the exception of JAK3. The α-tubulin derived from STAT3 membrane is shown as representative control. For p-JAK3 membranes, only the expression of α-tubulin was analyzed to assess comparable amounts of protein. These data are representative of 7 different experiments.

MePDN inhibits natural cytotoxicity and ERK phosphorylation in NK cells when stimulated with either IL-2 or IL-15

As previously shown, IL-2–induced NK cytotoxicity was sharply inhibited by MePDN treatment.18 We further analyzed whether the IL-15–induced NK cytotoxicity was affected as well. To this end, NK cells derived from the same donors were cultured with either IL-2 or IL-15 in the presence or absence of MePDN at different concentrations (see the first paragraph under “Results”): after 5 days of culture, cells were tested for their cytolytic activity against NK-susceptible target-cell lines. It has been shown that NK-mediated killing of human melanoma FO1 cell line involves NCRs (NKp46, NKp30, and NKp44) and NKG2D. On the other hand, lysis of LCL 721-221 B-EBV human cell line was mostly NKp46 dependent41 and the effect was enhanced by the simultaneous engagement of 2B4 receptor. Because the NKp46, NKG2D, and 2B4 surface expression was not affected by MePDN treatment,18 these cell lines were selected as target cells in cytolytic assays. Figure 3A shows a representative experiment (of 8 performed): it is evident that both IL-2– and IL-15–induced NK-cell cytotoxicity were inhibited in a dose-dependent manner.

MePDN inhibits both natural cytotoxicity and the cytokine-induced ERK phosphorylation. (A) NK cells were cultured for 5 days with IL-2 or IL-15 in the presence or absence (control = CTR) of MePDN concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 0.01 μg/mL (MePDN 0.5, MePDN 0.1, MePDN 0.01). A 4-hour 51Cr-release assay was performed in order to assess the cytolytic activity against the human HLA class I–negative, the 721-221 B-EBV (▪), or FO1 melanoma cell lines (⊡). The effector-target (E/T) ratio was 5:1. Data are expressed as percentage of target-cell lysis. This is representative of 8 experiments performed. (B) NK cells derived from the same donors were stimulated overnight with IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence or absence (control = CTR) of different MePDN concentrations from 1 to 0.01 μg/mL (MePDN 1, MePDN 0.5, MePDN 0.1, MePDN 0.01). Total-cell lysates were analyzed by WB using antihuman antibody against p-ERK1/2 and membranes were probed again with antibody recognizing the native protein in order to assess comparable amounts of proteins. In this figure, a representative experiment of 6 performed is shown.

MePDN inhibits both natural cytotoxicity and the cytokine-induced ERK phosphorylation. (A) NK cells were cultured for 5 days with IL-2 or IL-15 in the presence or absence (control = CTR) of MePDN concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 0.01 μg/mL (MePDN 0.5, MePDN 0.1, MePDN 0.01). A 4-hour 51Cr-release assay was performed in order to assess the cytolytic activity against the human HLA class I–negative, the 721-221 B-EBV (▪), or FO1 melanoma cell lines (⊡). The effector-target (E/T) ratio was 5:1. Data are expressed as percentage of target-cell lysis. This is representative of 8 experiments performed. (B) NK cells derived from the same donors were stimulated overnight with IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence or absence (control = CTR) of different MePDN concentrations from 1 to 0.01 μg/mL (MePDN 1, MePDN 0.5, MePDN 0.1, MePDN 0.01). Total-cell lysates were analyzed by WB using antihuman antibody against p-ERK1/2 and membranes were probed again with antibody recognizing the native protein in order to assess comparable amounts of proteins. In this figure, a representative experiment of 6 performed is shown.

Since lytic granule exocytosis depends on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 molecules, we also focused our studies on the IL-2– or IL-15–mediated activation of ERK1/2. Western blot analyses were performed on NK cells treated overnight as described above under “Western blot analysis.” Figure 3B shows a representative experiment of 6 performed: it is evident that MePDN concentrations (1 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL) that were inhibitory on STAT phosphorylation (Figure 2) also inhibited ERK1/2 phosphorylation primarily in NK cells cultured in IL-2 (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figure link at the top of the online article).

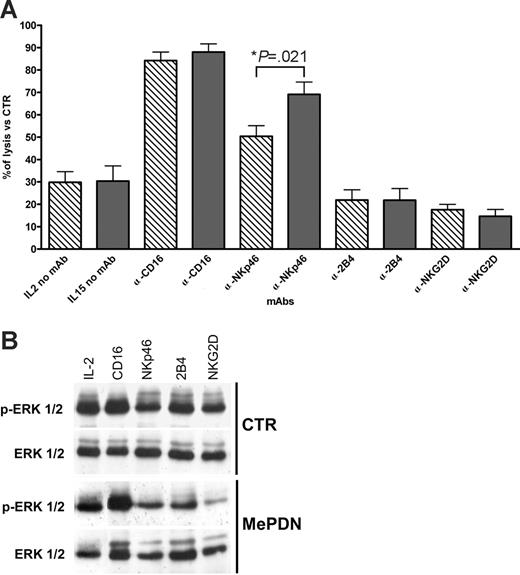

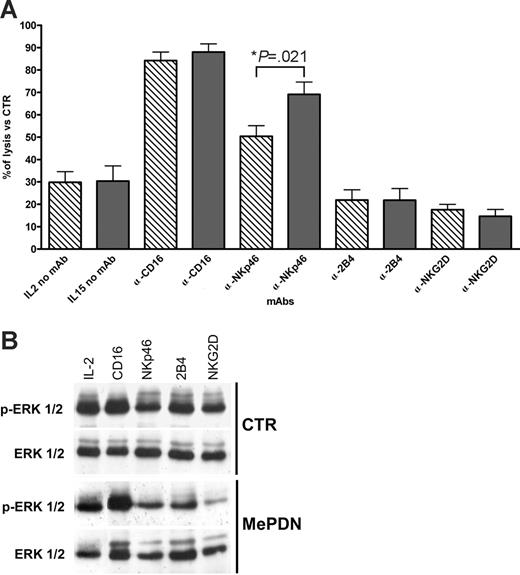

MePDN treatment inhibits NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity and ERK phosphorylation in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-15

In a previous study, we showed that the inhibitory effect of MePDN on the cytolytic activity of IL-2–cultured NK cells was due, at least in part, to the impairment of the NK receptor–mediated signaling as revealed by mAb-mediated redirected killing assays.18 Thus, we analyzed whether MePDN also exerted a similar effect on IL-15–cultured NK cells. We performed redirected killing assays using the FcγR+ P815 cell line as target cells. This would allow us to assess whether those activating NK receptors that were not modulated by steroid treatment could transduce an efficient signal upon mAb-mediated cross-linking. Figure 4 shows the percentage of NK receptor–induced cytotoxicity in MePDN-treated NK cells cultured in the presence of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) versus control NK cells cultured with the cytokines alone. Results are expressed as the mean percentage (±SEM) of cytolytic activity detected in 11 different donors. In agreement with our previous data,18 IL-2–activated NK cells treated with 0.5 μg/mL MePDN displayed a marked reduction of both spontaneous and mAb-induced cytotoxicity. A remarkable exception existed for NK cells stimulated with anti-CD16 and, at least in part, with anti-NKp46 mAbs. Note also that in NK cells cultured with IL-15, NKp46-mediated redirected killing was significantly less affected by MePDN treatment than in the presence of IL-2 (P = .021). On the other hand, cross-linking of NKG2D and 2B4 did not result in an efficient signal transduction with both cytokines.

MePDN inhibits NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity and ERK phosphorylation upon NK receptor cross-linking. (A) NK cells were cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) with or without MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity was assessed in a 4-hour 51Cr-release assay against the FcR-γ+ murine P815 cell line. The E/T ratio was 5:1. Data represent percentage of NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity of MePDN-treated NK cells cultured in the presence of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) versus control NK cells cultured with IL-2 or IL-15 alone. Results are expressed as the mean percentage (± SEM) of cytotoxicity analyzed in 11 experiments performed with 11 different donors. Statistical significance was checked by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (B) After 4 days of culture, NK cells derived from the same donor analyzed in panel A and cultured with IL-2 (100 U/mL) in the presence or absence of MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL were starved for 4 hours at 37°C in RPMI medium with no FCS or cytokines. Cells were then incubated with the indicated mAbs and cross-linked with F(ab′)2 GAM at 37°C for 5 minutes. Total-cell lysates were analyzed in order to detect p-ERK1/2. Cell membrane was reprobed with an antibody recognizing the native protein in order to assess comparable amounts of proteins. Similar results were obtained in the presence of IL-15. In this figure, a representative experiment of 4 is shown.

MePDN inhibits NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity and ERK phosphorylation upon NK receptor cross-linking. (A) NK cells were cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) with or without MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity was assessed in a 4-hour 51Cr-release assay against the FcR-γ+ murine P815 cell line. The E/T ratio was 5:1. Data represent percentage of NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity of MePDN-treated NK cells cultured in the presence of IL-2 (hatched bars) or IL-15 (gray bars) versus control NK cells cultured with IL-2 or IL-15 alone. Results are expressed as the mean percentage (± SEM) of cytotoxicity analyzed in 11 experiments performed with 11 different donors. Statistical significance was checked by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (B) After 4 days of culture, NK cells derived from the same donor analyzed in panel A and cultured with IL-2 (100 U/mL) in the presence or absence of MePDN at the final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL were starved for 4 hours at 37°C in RPMI medium with no FCS or cytokines. Cells were then incubated with the indicated mAbs and cross-linked with F(ab′)2 GAM at 37°C for 5 minutes. Total-cell lysates were analyzed in order to detect p-ERK1/2. Cell membrane was reprobed with an antibody recognizing the native protein in order to assess comparable amounts of proteins. Similar results were obtained in the presence of IL-15. In this figure, a representative experiment of 4 is shown.

Our data suggest that the impairment of cytolytic activity in steroid-treated NK cells could be the result of the parallel inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and of the inability of NK receptors to efficiently transduce activating signals. To this end, we analyzed whether ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced upon NK receptor cross-linking was affected by corticosteroid treatment. NK cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2 or IL-15 with or without MePDN (0.5 μg/mL). Figure 4B shows WB of a representative experiment (of 4 performed). Cross-linking of different activating receptors including CD16, NKp46, NKG2D, or 2B4 induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in control NK cells previously cultured with IL-2 alone. MePDN treatment strongly inhibited ERK2 and totally abrogated ERK1 phosphorylation. Remarkably, the activating signal mediated by CD16 was not significantly affected; these data confirm our results of redirected killing assays. It is also of note that CD16 normally induces higher levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation compared with other activating NK receptors. Similar results were obtained with IL-15–cultured NK cells (not shown). The inhibitory effect on ERK phosphorylation was also observed in freshly isolated NK cells cultured overnight in the presence or absence of MePDN without any cytokines. After labeling with the appropriate mAbs specific for one or another activating receptor, cells were stimulated with parafolmaldehyde-prefixed FcγR+ P815 cell line for 20 minutes at 37°C. This experimental setting allows receptor-induced ERK phosphorylation analysis in a more physiologic context in which cell-adhesion interactions are also involved (not shown).

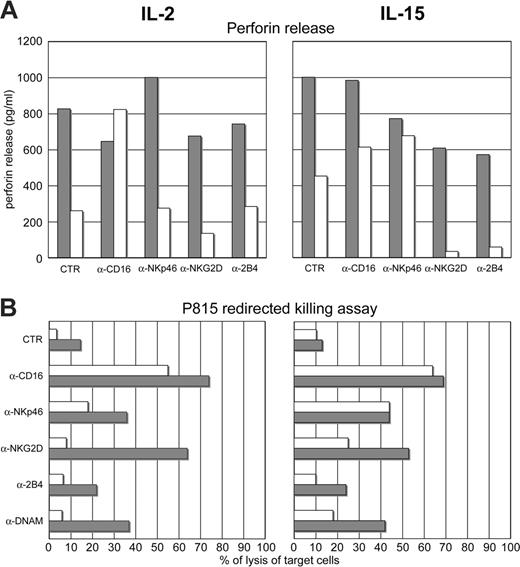

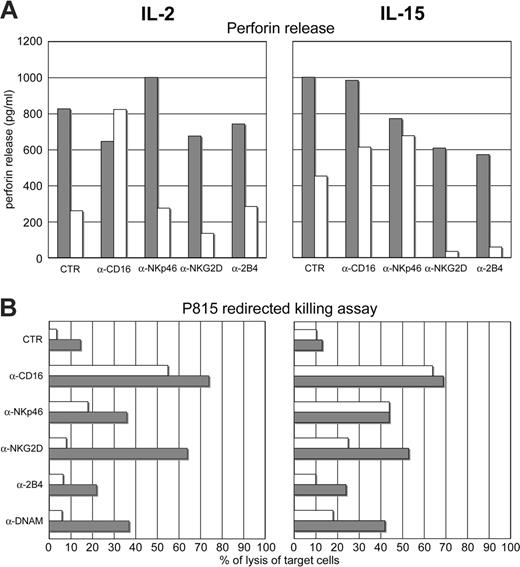

The MePDN-induced inhibition of NK receptor–dependent ERK2 Tyr phosphorylation correlates with the lack of granule exocytosis

It was important to clarify whether the inhibition of ERK phosphorylation correlated with reduced granule exocytosis. To this end, we analyzed perforin degranulation after cross-linking of the activating NK receptors in IL-2– or IL-15–cultured NK cells in the presence (Figure 5A, white bars) or absence (Figure 5A, gray bars) of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL). Perforin release was measured by ELISA assay. These experiments were performed in 4 donors. Importantly, in all 4 experiments the results of receptor-mediated cytotoxicity consistently paralleled those of perforin release. Figure 5 shows a representative experiment. Figure 5A (left) shows that IL-2–cultured NK cells, in the presence of MePDN (white bars), do not release perforin upon mAb-mediated cross-linking of the activating NK receptors, with the exception of CD16. These data are in agreement with those obtained in redirected killing assays performed with NK cells derived from the same donor (Figure 5B left). IL-15–exposed NK cells, cultured in the presence of MePDN (Figure 5A, white bars), efficiently released perforin upon cross-linking of CD16 or NKp46, whereas after cross-linking of NKG2D or 2B4 no release was detected (Figure 5A right). Notably, these data also paralleled those obtained in redirected killing assay from the same donor (Figure 5B right).

MePDN treatment inhibits perforin release: correlation with the impairment of NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity. (A) NK cells were cultured for 4 days in IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL). They were then stimulated by cross-linking the indicated NK receptors with appropriate mAbs. After overnight incubation at 37°C in the presence of RPMI + FCS alone, supernatants were collected and analyzed in an ELISA assay for quantitative determination of perforin release. Data are expressed in pg/mL. (B) The activating NK receptors analyzed in panel A were also tested for their ability to induce cytotoxicity in a redirected killing assay using the FcR-γ+ murine P815 cell line. NK cells derived from the same cultures as in panel A were analyzed after 4 days of culture. The E/T ratio was 5:1. Gray bars indicate IL-2– or IL-15–cultured control NK cells; white bars, MePDN-treated NK cells. This experiment is representative of 4 performed.

MePDN treatment inhibits perforin release: correlation with the impairment of NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity. (A) NK cells were cultured for 4 days in IL-2 (100 U/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/mL) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of MePDN (0.5 μg/mL). They were then stimulated by cross-linking the indicated NK receptors with appropriate mAbs. After overnight incubation at 37°C in the presence of RPMI + FCS alone, supernatants were collected and analyzed in an ELISA assay for quantitative determination of perforin release. Data are expressed in pg/mL. (B) The activating NK receptors analyzed in panel A were also tested for their ability to induce cytotoxicity in a redirected killing assay using the FcR-γ+ murine P815 cell line. NK cells derived from the same cultures as in panel A were analyzed after 4 days of culture. The E/T ratio was 5:1. Gray bars indicate IL-2– or IL-15–cultured control NK cells; white bars, MePDN-treated NK cells. This experiment is representative of 4 performed.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the molecular mechanisms involved in the MePDN-mediated inhibition of NK-cell activation and cytotoxicity. We show that NK cells cultured in either IL-2 or IL-15 display different susceptibility to MePDN treatment in terms of cell survival, proliferation, and NK receptor–mediated cytotoxicity. Moreover, we provide evidence that steroid-induced inhibition of NK-cell cytotoxicity not only results in down-regulation of surface expression or function of the activating receptors but also affects phosphorylation of ERK1/2, thus inhibiting granule exocytosis.

We have previously shown that MePDN induced a sharp inhibition of the surface expression of NKp30 and NKp44, 2 major activating receptors involved in natural cytotoxicity.18 This was originally detected in NK cells isolated from steroid-treated pediatric patients undergoing HSCT and subsequently confirmed in NK cells cultured in vitro with IL-2.18 While IL-2 is commonly used to activate and expand NK cells in vitro, it is conceivable that during the early phases of innate immune responses in vivo, IL-15 may exert a predominant role in NK-cell activation and function.31–34 This led us to characterize the effect(s) of corticosteroids also in IL-15–activated NK cells. In IL-15–cultured NK cells, cytofluorimetric analysis also revealed a sharp down-regulation of NKp30 and a lack of expression of NKp44 occurring in the presence of MePDN. However, in spite of a similar NKp30 and NKp44 surface down-regulation, the effect on NK-cell survival and proliferation was different in IL-2– or IL-15–cultured NK cells. Thus, NK cells cultured in the presence of different concentrations of IL-2 displayed higher susceptibility to MePDN compared with those cultured in different concentrations of IL-15. Parallel analysis revealed that IL-2–cultured NK cells displayed significant increases in their percentage of apoptotic cells compared with IL-15–cultured NK cells. Similarly, MePDN more markedly inhibited the NK-cell proliferation in response to IL-2 than in response to IL-15. Notably, although MePDN induced a marked (> 50%) down-regulation of CD132 expression, this inhibitory effect occurred both in IL-2– and IL-15–cultured NK cells. Therefore, the different capability to proliferate in the presence of the 2 cytokines and MePDN cannot only be explained by inhibition at the cytokine receptor level, although this effect may be more critical for the downstream events of IL-2 signaling.

The signal transduction initiated by IL-2 or IL-15 has been shown to involve Tyr phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3 and of JAK3/STAT5 molecules.38–40 Accordingly, the differential capability of MePDN to inhibit IL-2– versus IL-15–induced NK-cell survival and proliferation could reflect differences in susceptibility of STAT phosphorylation to steroid treatment. Previous data showed that in T lymphocytes, GCs can inhibit cell proliferation, IL-2/IL-15R CD122 and CD132 subunit surface expression, and STAT5 phosphorylation.42–45 In the present study, we show that STAT1 and STAT3 Tyr phosphorylation is sharply inhibited by MePDN in IL-2–cultured NK cells in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, in the presence of IL-15, the inhibitory effect was only detectable at the highest steroid concentrations. For example, at the corticosteroid concentration of 0.1 μg/mL, STAT phosphorylation was inhibited in IL-2–cultured but not in IL-15–cultured NK cells. Analysis of the JAK3/STAT5 pathway revealed some differences between the 2 cytokines: in spite of a similar MePDN-mediated inhibition of JAK3 Tyr phosphorylation, the downstream STAT5 Tyr phosphorylation was more affected by MePDN in the presence of IL-2 than in the presence of IL-15.

Traditionally, IL-2/IL-15–dependent activation of STAT5 is thought to depend on JAK3 phosphorylation triggered through the CD132 subunit. Our present data might suggest that in NK cells, IL-2/IL-15–dependent STAT5 phosphorylation may be uncoupled from JAK3 phosphorylation. This could imply the involvement of other IL-2R/IL-15R subunits, occurring when a marked down-regulation of CD132 expression takes place. A possible substitute could be the IL-2R/IL-15R CD122 subunit. Indeed, its expression in NK cells, different from what is described in T cells,42 is not down-regulated by MePDN (not shown), and thus CD122 could directly trigger STAT5 phosphorylation, as reported by previous studies.46–48

Moreover, the inhibitory activity of MePDN displayed a long-lasting effect and could thus also affect survival and proliferation of NK cells, mainly acting on STAT5 phosphorylation. In this context, IL-15–dependent activation of STAT5 has been shown to induce a set of genes involved in the control of apoptosis (eg, BclxL), proliferation (eg, CCND1), and signal transduction (eg, SOCS3).49 Preliminary results would indicate that in NK cells, BclxL is differently affected by MePDN in the presence of IL-2 or IL-15. Moreover, we could detect surface expression of membrane-bound IL-15 upon NK-cell exposure for 4 hours to high doses of IL-15 and subsequent culture for 48 hours in the presence or absence of MePDN (in the absence of IL-15; C.V., unpublished data, October 2006). This finding might suggest that NK cells, similarly to T cells, can use this form of membrane-bound IL-15 for their survival.50 These observations might support the notion that IL-15 could represent an important mediator for NK-cell homeostasis in vivo.51–54

Notably, in our experimental system, the steroid-mediated effect on NK-cell survival and proliferation did not necessarily parallel the effect on NK-cell activation and cytotoxicity, thus suggesting that these processes are differently regulated. Indeed, MePDN inhibited at a similar extent the natural cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines mediated by NK cells cultured with IL-2 or IL-15. On the other hand, the surface expression of adhesion molecules or conjugate formation was not inhibited by steroid treatment (not shown). Remarkably, it has been suggested that conjugate formation and cytotoxicity do not necessarily correlate.55 Inhibition of cytotoxicity is likely to reflect primarily the down-regulation of NKp30 and NKp44 surface expression and the inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Indeed, ERK1/2 activation has been reported to play a crucial role in NK-cell cytotoxicity; in particular ERK2 would be the final mediator of perforin and granzyme B granule polarization toward target cells.28 Notably, in the presence of MePDN, a sharp decrease of perforin release could be detected after cross-linking of NK receptors. Comparative analysis of cytotoxicity and perforin release in IL-2– or IL-15–cultured NK cells revealed that MePDN inhibited the function triggered by various activating NK receptors but not that induced by CD16. Interestingly, cross-linking of CD16 (but not of the other activating NK receptors), also in the presence of MePDN, could efficiently induce ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Remarkably, we found that NK cells from different donors can display different susceptibility to steroid treatment in the presence of IL-15. Thus, in 3 of 11 donors, cytotoxicity mediated by NKp46 was not inhibited by steroid treatment. Remarkably, statistical analysis performed in the 11 donors revealed that NKp46-mediated cytotoxicity was significantly less affected in the presence of IL-15 than in the presence of IL-2. These results could suggest that IL-15 might, in some individuals, “rescue” the NKp46-mediated natural cytotoxicity. It is of note that CD16 and NKp46 share the signaling pathway via the same ITAM-bearing molecules. It has been suggested that differences in amino acid–charged residues in the transmembrane region may be, at least in part, responsible for differences in CD16- and NKp46-mediated activation, as we observed in the presence of IL-2.56

Regarding the inhibitory effect on ERK phosphorylation, it has been reported that GCs interfere with the MAPK signaling pathways, resulting in reduced ERK activation.19 Our results suggest that GCs interfere with ERK phosphorylation in NK cells with a mechanism that selectively inhibits molecules that are crucial for natural cytotoxicity but not for ADCC. In this context, the calcium signal and degranulation mediator PLCγ2 could represent a likely candidate.57,58

During the process of cell-mediated cytotoxicity, a correct assembly of the immunologic synapse (IS) with clustering of lipid rafts and recruitment of protein kinases is crucial for signal transduction.59,60 In this context, MePDN-treated NK cells might represent a useful model to precisely determine the molecular interactions occurring in NK cells at the level of IS, signal transduction, raft polarization, and cytoskeletal movement.

Our data imply that the different abilities of NK cells to respond to GCs in the course of anti-inflammatory therapies may depend on the cytokine microenvironment. Thus, in the presence of IL-15 (but not of IL-2), NK cells could display a better ability to survive and promptly restore their functions, after dismission of steroid therapy.

In recent years, it became evident that NK cells can play a central role in the positive clinical outcome of allogeneic HSCT to cure acute myeloid leukemias, particularly in the case of haploidentical HSCT.18,61 The role of NK cells, generated from HSCs, appears to be primarily confined to the early events that follow bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and is due to both their graft-antileukemia effect and their ability to provide a first line of defense against lethal viral infections. In this context, the knowledge of the effect of GCs on the phenotypic and functional properties of NK cells would allow an early detection of a possible impairment of NK-cell function. Since NK cells can provide an important tool for defense against leukemias and tumors, they also represent excellent candidates to be used in adoptive immunotherapy in selected neoplastic diseases.34,62,63 Accordingly, the knowledge of possible interferences of GCs or other immunosuppressive drugs with NK-cell function is particularly relevant for correct timing of NK-cell infusion and steroid treatment. In addition, since MePDN exerts different effects on NK cells depending on which cytokine has been used for their activation (IL-2 or IL-15), one may choose the most appropriate cytokine milieu to activate NK cells in vitro before infusion in adoptive immunotherapy.

Authorship

Contribution: L.C. designed the work, performed most of the experimental (molecular and cellular experiments) work, and wrote the paper. C.V. designed and coordinated the work, performed phenotypic and functional experiments in NK cells, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. S.M. performed Western-blot experiments. F.C. performed phenotypic and functional cellular experiments and prepared the figures. B.A. contributed to analysis and discussion of the data and reviewed the paper. L.M. contributed to the discussion, wrote the paper, and provided financial support. M.C.M. supervised the project, reviewed the paper, and provided financial support.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

L.C. and C.V. contributed equally to the present study.

Correspondence: Chiara Vitale, Laboratorio Oncologia Sperimentale D Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro, L.go R.Benzi 10 16132, Genova, Italy; e-mail chiara_vitale@hotmail.com.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This work was supported by grants awarded by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC); Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS); Ministero della Salute–RF 2002/149; Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MIUR); FIRB-MIUR project-RBNE017B4; and European Union FP6, LSHB-CT-2004-503319-AlloStem (the European Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained). Also the financial support of Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino, Italy is gratefully acknowledged.