In this issue of Blood, Sargin and colleagues identify a mutation in the negative regulator c-Cbl in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that mirrors the effects seen with oncogenic Flt3 receptors. Thus, an alternative mechanism for the inappropriate activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in tumors occurs through inactivation of a negative regulator.

Mutations in Flt3, a type III RTK, are the most common genetic lesions found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), representing about a third of all cases.1,2 In addition, Flt3 is overexpressed in most cases of AML. It is well known that Cbl proteins function as E3 ligases that ubiquitinate activated RTKs and direct their trafficking through endosomal compartments, resulting in degradation by lysosomes.3 Most of these studies have focused on the fate of the EGF receptor; however, little is known about the role of Cbl proteins in regulating Flt3, or whether altered forms of Cbl contribute to the development of human leukemias.

In this issue of Blood, Sargin and colleagues make a number of novel and significant findings demonstrating that c-Cbl plays a key role in determining the fate and signaling activity of Flt3. These findings conclusively prove that c-Cbl targets both ligand-activated wild-type Flt3 and oncogenic Flt3 for ubiquitination and degradation. Also examined is an oncogenic form of c-Cbl, known as Cbl-70Z, which has lost its ability to function as an E3 ligase. Sargin and colleagues show that Cbl-70Z not only abolishes Flt3 ubiquitination and degradation, but also confers a constitutively active phenotype to the receptor.

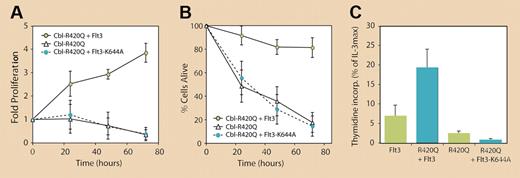

Of particular note is the identification of a RING finger domain mutation in c-Cbl from an AML patient in whom an arginine residue is substituted with a glutamine at position 420 (R420Q). This residue is conserved in all Cbl proteins, including in Caenorhabditis elegans,4 and is a predicted contact point for c-Cbl's interaction with E2-ubiquitin–conjugating enzymes.5 As a consequence, Sargin and colleagues show that this mutation inhibits c-Cbl–directed Flt3 ubiquitination and degradation. This finding is significant, as it represents the first example of a c-Cbl mutation that is likely to be a causative event in the development of a human tumor. Also shown are the biochemical effects of the R420Q mutation where it, like Cbl-70Z, activates Flt3 and its downstream pathways in a ligand-independent manner. Thus, c-Cbl (R420Q) and Cbl-70Z additionally act on Flt3 through a positive mechanism to constitutively enhance receptor activity. This indicates that the effects of these proteins cannot be explained solely through a dominant-negative mechanism that simply blocks endogenous c-Cbl E3 ligase activity. The biological consequence of this enhanced activity is that 32D cells expressing c-Cbl (R420Q) (or Cbl-70Z) plus wild-type Flt3 survive and proliferate in the absence of ligand (see figure). Sargin and colleagues also show that growth-factor independence conferred by these altered forms of c-Cbl can be blocked with an Flt3-specific inhibitor or by the expression of kinase-dead Flt3.

The mutant c-Cbl RING finger protein R420Q confers long-term survival and growth-factor–independent proliferation of 32D cells exclusively in the presence of Flt3. However, kinase-dead Flt3 (K644A) fails to induce autonomous cell growth in the presence of c-Cbl (R420Q). See the complete figure in the article beginning on page1004.

The mutant c-Cbl RING finger protein R420Q confers long-term survival and growth-factor–independent proliferation of 32D cells exclusively in the presence of Flt3. However, kinase-dead Flt3 (K644A) fails to induce autonomous cell growth in the presence of c-Cbl (R420Q). See the complete figure in the article beginning on page1004.

These findings will be of considerable interest to researchers and oncologists, as they demonstrate that aberrant negative regulators of RTK signaling can contribute to the development of human tumors. As a result, it is possible that patients without RTK mutations could still suffer consequences equivalent to constitutive RTK signaling and would therefore benefit from tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Furthermore, since c-Cbl can down-regulate oncogenic forms of RTKs, it is possible that harnessing the natural restraining power of Cbl proteins could offer an alternate approach to the suppression of constitutively active RTKs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

Note added in proof. An article by Caligiuri et al that identifies additional AML patients with RING finger and linker domain mutations in c-Cbl and Cbl-b appears in this issue on page1022.