In this issue of Blood, Schulze zur Wiesch and colleagues unmask strong CD4+ T-cell responses in some chronically HCV-infected patients as remainders of a previously resolved heterologous HCV infection rather than responses to the current persisting infection, further questioning protective immunity to heterologous HCV infection.

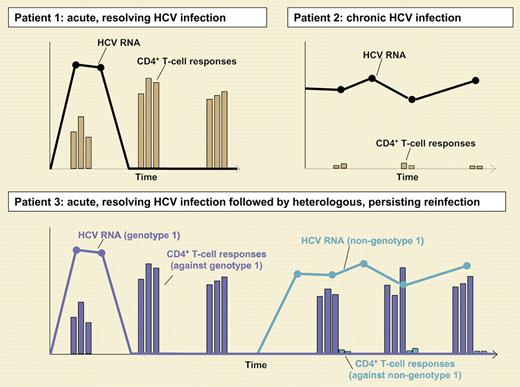

Increasing evidence suggests that the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response plays a key role in the outcome of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Consistent with this concept, individuals with resolved HCV infection harbor strong CD4+ T-cell responses against multiple CD4+ T-cell epitopes (patient 1 in the figure), whereas patients with persistent infection lack a significant CD4+ T-cell response (patient 2 in the figure).1,2 Strikingly, however, a subgroup of patients with persistent HCV non–genotype 1 infection shows a CD4+ T-cell response similar to individuals with resolved infection, when being studied with HCV genotype 1–derived peptides. These results led to the hypothesis that the CD4+ T-cell responses in these chronically HCV-infected patients may represent responses to a previous, resolved HCV genotype 1 infection rather than the current HCV non–genotype 1 infection (patient 3 in the figure).3,4 This hypothesis is supported in the elegant study by Schulze zur Wiesch and colleagues in this issue of Blood, which compares CD4+ T-cell responses in 24 patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection and 20 patients with chronic HCV non–genotype 1 infection using a full-breadth approach. Importantly, the large majority of CD4+ T-cell responses were detected in 4 HCV non–genotype 1 infected patients who were positive for HCV genotype 1–specific antibodies, indicating a previous, resolved HCV genotype 1 infection. In addition, these responses recognized peptides derived from HCV genotype 1, but not peptides derived from the autologous non–genotype 1 virus.

Typical CD4+ T-cell responses in 3 patients with different courses of HCV infection. Patient 1 clears the virus in the presence of sustained vigorous and multispecific CD4+ T-cell responses. In patient 2, who has chronic HCV infection, CD4+ T-cell responses are hardly detectable. Patient 3 goes through acute, resolving HCV genotype 1 infection, resulting in sustained vigorous and multispecific CD4+ T-cell responses. Later, patient 3 is reinfected with a heterologous, HCV non–genotype 1 infection. The vigorous and multispecific CD4+ T-cell responses detectable in the patient represent remainders from the previous genotype 1 infection and do not prevent persistence of the HCV non–genotype 1 infection.

Typical CD4+ T-cell responses in 3 patients with different courses of HCV infection. Patient 1 clears the virus in the presence of sustained vigorous and multispecific CD4+ T-cell responses. In patient 2, who has chronic HCV infection, CD4+ T-cell responses are hardly detectable. Patient 3 goes through acute, resolving HCV genotype 1 infection, resulting in sustained vigorous and multispecific CD4+ T-cell responses. Later, patient 3 is reinfected with a heterologous, HCV non–genotype 1 infection. The vigorous and multispecific CD4+ T-cell responses detectable in the patient represent remainders from the previous genotype 1 infection and do not prevent persistence of the HCV non–genotype 1 infection.

These results extend previous observations in chimpanzees and smaller cohorts of patients, showing the absence of protection against a heterologous challenge. This study also provides the first evidence why a T-cell response induced by a previous resolved HCV infection may not confer protection against a heterologous challenge. Usually, individuals with resolved HCV infection target a number of immunodominant and highly conserved CD4 epitopes that are widely cross-reactive between different genotypes. The patients with heterologous reinfection identified in this study, however, target subdominant viral epitopes with high intergenotype variance. Thus, although genotype 1–specific T cells are detectable, these responses do not recognize peptides of the current, autologous HCV non–genotype 1 infection. Two different mechanisms could explain this interesting finding. First, the patients might have resolved the previous genotype 1 infection without targeting the usual immunodominat, cross-reactive CD4 epitopes. Second, and more tempting to assume, the reinfecting, heterologous HCV may evade the immune response by suppressing T-cell responses against these immunodominant, cross-reactive epitopes, while CD4+ responses against only weakly cross-reactive and thus irrelevant epitopes are sustained. This phenomenon has been called “antigenic sin” in other viral infections.

In sum, this study suggests that genotype 1–specific CD4+ T-cell responses do not confer protection against heterologous non–genotype 1 challenge. These results have important implications for vaccine development, because they suggest that the induction of promiscuous and broadly reactive CD4+ T-cell responses is required for protection from heterologous reinfection and that this does not necessarily occur during natural infection. Clearly, CD4+ T cells do not always help, especially if they only represent survivors of a previous battle.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■