Abstract

The multistep, coordinated process of T-cell chemotaxis requires chemokines, and their chemokine receptors, to invoke signaling events to direct cell migration. Here, we examined the role for CCL5-mediated initiation of mRNA translation in CD4+ T-cell chemotaxis. Using rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, our data show the importance of mTOR in CCL5-mediated T-cell migration. Cycloheximide, but not actinomycin D, significantly reduced chemotaxis, suggesting a possible role for mRNA translation in T-cell migration. CCL5 induced phosphorylation/activation of mTOR, p70 S6K1, and ribosomal protein S6. In addition, CCL5 induced PI-3′K–, phospholipase D (PLD)–, and mTOR-dependent phosphorylation and deactivation of the transcriptional repressor 4E-BP1, which resulted in its dissociation from the eukaryotic initiation factor-4E (eIF4E). Subsequently, eIF4E associated with scaffold protein eIF4G, forming the eIF4F translation initiation complex. Indeed, CCL5 initiated active translation of mRNA, shown by the increased presence of high-molecular-weight polysomes that were significantly reduced by rapamycin treatment. Notably, CCL5 induced protein translation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9, known mediators of migration. Taken together, we describe a novel mechanism by which CCL5 influences translation of rapamycin-sensitive mRNAs and “primes” CD4+ T cells for efficient chemotaxis.

Introduction

Directed cell migration is a tightly regulated process, critical for numerous biologicl processes including proper tissue development, wound healing, and protection against invading pathogens. Chemokines are soluble, extracellular chemoattractant molecules that play a vital role in many of these biologic processes. The chemokines are a large family of mainly secreted, 8- to 10-kDa proteins subdivided into 4 families based on the relative positioning of the first 2 cysteine residues near the N-terminus.1-3 Chemokine ligands interact with 7 transmembrane, G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) to induce directed cellular migration. Secreted chemokines bind to heparin-like glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) normally expressed on proteoglycan components of the cell surface and extracellular matrix, thereby creating a concentration gradient allowing immune cells to migrate via a haptotactic mechanism.4-9 These immobilized chemokines allow leukocytes to stop rolling, promote extravasation, and regulate directional migration.

T-cell chemotaxis is a process that requires the activation and redistribution of a number of signaling, adhesion, and cytoskeletal molecules at the cell surface.10,11 CCL5/RANTES is a member of the β-chemokines and is chemotactic for Th1 T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells through the expression of CCR1 and/or CCR5.12-16 It is now clear that signaling through CCR5 controls a multitude of cellular functions, including chemotaxis, proliferation, cytokine production, survival, and apoptosis.17-24 Through studies with PI-3′K inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002, it is known that CCL5-mediated PI-3′K activation is critical for chemotaxis.25-27 Chemokines activate the PI-3′Kγ isoform by the βγ subunits of trimeric G proteins at the cell membrane, although contributions from other isoforms cannot be discounted.28-30 Studies with the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, have underscored the role for mTOR in fibronectin and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) induced cellular migration downstream of PI-3′K.31-34 mTOR possesses a carboxy-terminal region sharing significant homology with lipid kinases, especially with PI-3′K, and has been assigned to a larger protein family termed the PIKKs (phosphoinositide kinase-related kinases).35 mTOR exists in 2 complexes: mTOR Complex1, which is sensitive to rapamycin and phosphorylates p70 S6K1 and initiation factor 4E–binding proteins (4E-BPs), and mTOR Complex2, which is rapamycin-resistant and phosphorylates PKB.36-38 mTOR Complex1 is responsible for the phosphorylation of S6K1 on threonine 389.36,39,40 Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 at the priming site, threonine 37/46, and additional sites serine 65 and threonine 70 are LY294002 and rapamycin sensitive (albeit to various degrees), indicating that 4E-BP1 is regulated by both mTOR and PI-3′K.36,41 Another important modulator of mTOR activity is phospholipase D (PLD), for which the primary alcohol, 1-butanol, but not tert-butanol, blocks PLD-mediated S6K activation and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation in several cell types.42-44 Indeed, CCL5 has been shown to stimulate PLD activity in Jurkat T cells, but its role in chemotaxis has not been studied.19 mTOR-dependent modulation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 has been implicated in several cellular processes, including metabolism, nutrient sensing, translation, and cell growth.35,45 Here, we examine for the first time the effects of CCL5 on the translation initiation of rapamycin-sensitive mRNAs, and their contribution to CD4+ T-cell chemotaxis.

mRNA translation is an energy-consuming process that is highly regulated at multiple levels in mammalian cells. Changes in translation rates often correlate with changes in the level of eIF4E, and thus its availability is under tight control. Three eIF4E inhibitory proteins, the 4E-BPs (4E-BP1-3), regulate mRNA translation by sequestering eIF4E.46 mTOR regulates translation by modulating the availability of eIF4E through hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1.47 The mRNA 5′-cap structure is bound by eIF4F, a heterotrimeric protein complex composed of an eIF4G backbone, the cap-binding eIF4E, and the RNA helicase, eIF4A. This complex facilitates ribosome binding and passage along the 5′-UTR (untranslated region) toward the initiation codon.48,49 In addition, mTOR controls the translation of 5′-TOP (tract of oligopyrimidines) mRNAs that often encodes for cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins.50,51 Although 5′-TOP mRNA translation is sensitive to rapamycin, the exact mechanism is unclear, and recent studies have shown that S6K1 and its effector molecule rpS6 are dispensable for their translation.52 Taken together, mTOR is a crucial regulator of the translational machinery by (1) directly affecting eIF4F availability for 5′-capped mRNA translation initiation and (2) up-regulating ribosomal protein levels through modulation of 5′-TOP mRNA translation.

Control of translational machinery is an important contributor to the overall gene expression. Translational control allows for the rapid production of proteins without the need for mRNA transcription, processing, and export into the cytoplasm. In the present study, we examined the role for CCL5-mediated initiation of mRNA translation in the context of CD4+ T-cell chemotaxis. Specifically, we focused on the translation of rapamycin-sensitive mRNAs that contain significant secondary structures in their 5′-UTR. We describe a novel mechanism by which CCL5 directly modulates protein levels to “prime” cells for directed cellular migration, thus allowing for a more rapid and effective immune response.

Methods

Cells and reagents

Human peripheral blood–derived T cells were isolated from healthy donors as previously described.20 Approval was obtained from the University Health Network (UHN) Research Ethics Board (REB) for these studies. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, CD4+ T cells were purified using the RosetteSep T-cell enrichment cocktail according to manufacturer's specifications (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). T cells were subsequently activated in the presence of plate-bound 10 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) and 5 μg/mL anti-CD28 antibody (eBiosciences) with soluble 5 ng/mL hrIL-12 (Bioshop Canada, Burlington, ON) and 2.5 μg/mL anti–IL-4 antibody (eBiosciences) for 2 days, and further expanded in culture supplemented with 100 U/mL hrIL-2 (Bioshop Canada) for 3 days. T-cell purity and CCR5 expression were confirmed at day 5 by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis using antihuman CCR5 antibody (2D7) and antihuman CD3 antibody (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Antibodies for phospho-eIF4E (Ser 209), eIF4E, phospho-rpS6 (Ser 235/236), rpS6, phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46), phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 70), 4E-BP1, phospho-p70S6K1 (Thr 389), p70S6K1, phospho-mTOR (Ser 2448), and mTOR were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies for human cyclin D1 (DCS-6), eIF4E (P-2), and eIF4G (H-300) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Murine monoclonal antitubulin antibody was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Polyclonal rabbit antibody against human MMP-9 was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Inhibitors cycloheximide, actinomycin D, rapamycin, and LY294002 were all obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). 1-Butanol and tert-butanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, ON). AS-252424 was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). 2,3-Diphosphoglycerate (DPG) has been shown to inhibit PLD and was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.53,54 CCL3 (LD78β) was purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). CCL5 was a generous gift from Dr Amanda Proudfoot (Geneva Research Center, Merck Serono International, Geneva, Switzerland).

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

T cells were serum starved in RPMI 1640/0.5% BSA overnight to reduce the effects of the various growth factors found in fetal calf serum (FCS) on mTOR and protein translation. Cells were incubated with 10 nM CCL5 for the times indicated, collected, washed 2 times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in 100 μL lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 2 μg/mL pepstatin A). For all experiments using inhibitors, cells were pretreated for 1 hour with the amount of inhibitor indicated prior to CCL5 treatment. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (BioRad laboratories, Hercules, CA). Protein lysate (30 μg) was denatured in sample reducing buffer and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane followed by blocking with 5% BSA (wt/vol) in TBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were probed with the specified antibodies overnight in 5% BSA (wt/vol) in TBST (0.1% Tween-20) at 4°C and the respective proteins visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For immunoprecipitation assays, 2 μg mouse anti-eIF4E monoclonal antibody (P-2) or rabbit anti-eIF4G polyclonal antibody (H-300) was added to 500 μg protein lysates. Appropriate whole molecule mouse or rabbit IgG antibody (2 μg; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) was used as control. Antibodies were pulled down with protein A/G-sepharose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and washed 6 times with lysis buffer. Beads were then denatured in 5× sample reducing buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells (106) were incubated with mouse antihuman CCR5 antibody for 45 minutes on ice and washed 3 times with ice-cold FACS buffer (PBS/2% FCS). Cells were then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti–mouse IgG antibody (eBiosciences). As control, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated isotype control IgG antibody (eBioscience). Cells were analyzed using the FACSCalibur and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Chemotaxis assay

T-cell chemotaxis was assayed using 24-well Transwell chambers with 5 μm pores (Corning, Corning, NY). A total of 105 cells in 100 μL chemotaxis buffer (RPMI 1640/0.5% BSA) were placed in the upper chambers. CCL5, diluted in 600 μL chemotaxis buffer, was placed in the lower wells and the chambers were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Migrated cells located in the bottom wells were collected, washed once with PBS, and counted by FACS. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. In experiments involving inhibitors, cells were pretreated for 1 hour at the indicated inhibitor concentrations and placed in the upper chambers. Cell viability, as measured by PI staining (Figure S2A, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), was not affected at any of the concentrations of inhibitors used in this study.

Semiquantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

T cells (107) were serum starved in RPMI 1640/0.5% BSA overnight and incubated at 37°C with 10 nM CCL5 for the times indicated. Cells were collected, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and lysed with the RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The resulting lysates were homogenized with a QIA shredder column, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD). cDNA was then serially diluted in dH2O as indicated and amplified for human cyclin D1, MMP-9, and GAPDH using the following primers and conditions: cyclin D1, FP 5′ atggaacaccagctcctgtgctgc 3′ and RP 5′ tcagatgtccacgtcccgcacgt 3′ (95°C for 1 minute, 65.5°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute, 35 cycles); MMP-9, FP 5′ cgtggttccaactcggtttg 3′ and RP 5′aagccccacttcttgtcgct 3′ (95°C for 1 minute, 58°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute, 30 cycles); GAPDH, FP 5′ aaggctgagaacgggaagcttgtcatcaat 3′ and RP 5′ ttcccgtctagctcagggatgaccttgccc 3′ (95°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute, 30 cycles).

Polysome gradients

Activated CD4+ T cells were serum starved and treated with 10 nM CCL5 for 1 hour before lysis in ice-cold Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with RNaseOut RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 500 U/mL. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 3000g for 2 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was supplemented with 665 μg/mL heparin, 150 μg/mL cycloheximide, 20 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF and centrifuged at 15 000g for 5 minutes at 4°C to eliminate mitochondria. The supernatant was then layered onto a 30-mL linear sucrose gradient (15%-40% sucrose [wt/vol] supplemented with 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, and 0.5 mg/mL heparin) and centrifuged in a SW32 swing-out rotor (Beckman, Hialeah, FL) at 187 000g for 2 hours at 4°C without a brake. Fractions (750 μL) were carefully collected from the center of the column using a pipette and digested with 100 μg proteinase K in 1% SDS and 10 mM EDTA for 30 minutes at 37°C. RNAs were extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol followed by ethanol precipitation and dissolved in RNase-free water before being analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% denaturing formaldehyde agarose gels to examine polysome integrity. RNA from each fraction was quantified at optical density (OD) of 254 nm. OD readings for each fraction were plotted as a percentage of the total RNA of all fractions to facilitate visual comparisons, and are shown as a function of gradient depth.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed t test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between groups.

Results

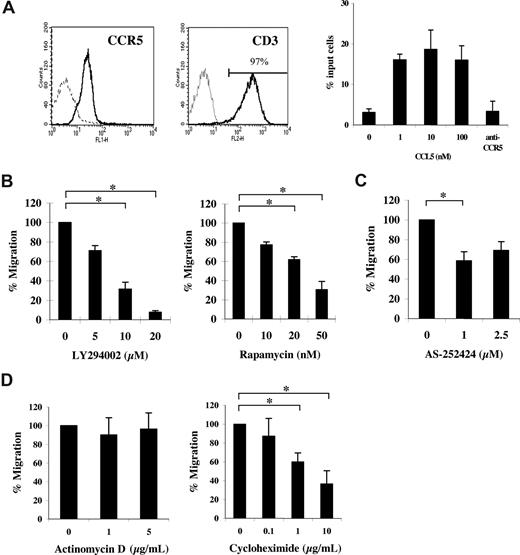

CCL5-mediated chemotaxis of activated CD4+ T cells is mTOR dependent

Studies were undertaken to examine the influence of mRNA translational events on CCL5-mediated chemotaxis. Ex vivo activation of peripheral blood (PB) CD4+ T cells with cytokines induced CCR5 expression (Figure 1A left panel). Notably, we observed no expression of CCR1 in our activated CD4+ T cells (data not shown). T-cell populations used for subsequent experiments were consistently greater than 95% CD3+ and CD4+ (data not shown). CCR5 expression on activated T cells correlated with a functional response to CCL5, as evidenced by dose-dependent migration toward CCL5 and abrogation of migration by pretreatment with anti-CCR5 antibody (5 μg/mL, 2D7; Figure 1A right panel). Subsequent experiments examined the effects of the PI-3′K inhibitor LY294002 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin on CCL5-mediated chemotaxis. As shown in Figure 1B, pretreatment with either LY294002 or rapamycin significantly reduced CCL5-mediated T-cell chemotaxis in a dose-dependent manner. The data suggest that both PI-3′K and mTOR play a role in CCL5-mediated T-cell migration. The PI-3′Kγ–specific inhibitor, AS-252424, also reduced CCL5-mediated T-cell chemotaxis (Figure 1C). Interestingly, experiments with CCL3/MIP1α, another agonist ligand of CCR5, revealed that CCL3-mediated T-cell migration was insensitive to rapamycin at doses as high as 100 nM (Figure S1A). Notably, we find that both CCL3/MIP1α and CCL4/MIP1β are poor effectors of CCR5-mediated T-cell chemotaxis compared with CCL5, with CCL3 exhibiting superior chemotactic activity to CCL4. Specifically, whereas 10 nM CCL5 exhibits a migration index approximately 5-fold over control (Figure 1A), the migration index for 10 nM CCL3 is approximately 2-fold in identical in vitro chemotactic transwell experiments. To further investigate the involvement of mRNA translation on CCL5-mediated T-cell chemotaxis, cells were pretreated with cycloheximide or actinomycin D, inhibitors of mRNA translation and transcription, respectively. As shown in Figure 1D, cycloheximide but not actinomycin D significantly reduced CCL5-mediated T-cell chemotaxis in a dose-dependent manner. The reduction in CCL5-mediated T-cell chemotaxis by inhibitors at the doses used is not due their toxicity or their ability to alter cell adhesion (Figure S2A,B).

CCL5-mediated chemotaxis of activated CD4+ T cells is dependent on PI-3′K and mTOR. (A) Activated peripheral blood (PB) T cells were stained with anti-CCR5 and anti-CD3 antibodies (solid line) or isotype controls (dotted line) and analyzed by FACS. CCL5-mediated chemotaxis is presented as migrated cells per well. (B) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either DMSO (carrier) or the specified inhibitors for 1 hour at the concentrations indicated, and CCL5-mediated chemotaxis was measured using 10 nM CCL5. The data are presented as percentage migration, with the number of migrated cells at 10 nM CCL5 taken as 100%. Representatives of 3 independent experiments are shown (± SD); *P < .05. (C) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either ethanol (carrier) or AS-252424 for 1 hour at the concentration indicated, and CCL5-mediated chemotaxis measured using 10 nM CCL5. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (± SD); *P < .05. (D) Activated PB T cells pretreated with either DMSO (carrier), cycloheximide, or actinomycin D for 30 minutes at the concentrations indicated. The data represent means plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

CCL5-mediated chemotaxis of activated CD4+ T cells is dependent on PI-3′K and mTOR. (A) Activated peripheral blood (PB) T cells were stained with anti-CCR5 and anti-CD3 antibodies (solid line) or isotype controls (dotted line) and analyzed by FACS. CCL5-mediated chemotaxis is presented as migrated cells per well. (B) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either DMSO (carrier) or the specified inhibitors for 1 hour at the concentrations indicated, and CCL5-mediated chemotaxis was measured using 10 nM CCL5. The data are presented as percentage migration, with the number of migrated cells at 10 nM CCL5 taken as 100%. Representatives of 3 independent experiments are shown (± SD); *P < .05. (C) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either ethanol (carrier) or AS-252424 for 1 hour at the concentration indicated, and CCL5-mediated chemotaxis measured using 10 nM CCL5. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (± SD); *P < .05. (D) Activated PB T cells pretreated with either DMSO (carrier), cycloheximide, or actinomycin D for 30 minutes at the concentrations indicated. The data represent means plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

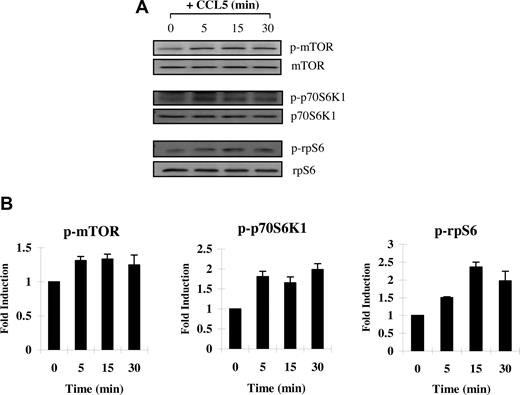

CCL5 induces phosphorylation of mTOR, p70 S6 kinase, and S6 ribosomal protein

Next, we examined CCL5-mediated phosphorylation/activation of mTOR. mTOR is phosphorylated on serine 2448 by the PI-3′K/PKB pathway.55 In turn, phosphorylated/activated mTOR can directly phosphorylate p70 S6K1 at threonine 389 in vitro.56 In time course studies, we show that T cells treated with 10 nM CCL5 induced the rapid phosphorylation/activation of mTOR on serine 2448 and S6K1 on threonine 389, within 5 minutes (Figure 2A,B). We also showed a CCL5-mediated phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein (rpS6), a known downstream effector of S6K1, on serine 235/236 (Figure 2C). Although rpS6 does not regulate translation of 5′-TOP mRNAs, phosphorylation remains an acceptable readout for S6K1 activity. Taken together, the data suggest that CCL5 is able to activate the mTOR/S6K1 pathway to potentially influence translation initiation.

CCL5-dependent phosphorlyation of mTOR, p70 S6K1, and ribosomal protein S6 in T cells. Activated PB T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with (A) anti–phospho-mTOR (Ser 2448) antibody, anti–phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr 389) antibody, or anti–phospho-rpS6 (Ser 235/236) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for the appropriate loading controls. (B) The relative fold increase in phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments plus or minus SD.

CCL5-dependent phosphorlyation of mTOR, p70 S6K1, and ribosomal protein S6 in T cells. Activated PB T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with (A) anti–phospho-mTOR (Ser 2448) antibody, anti–phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr 389) antibody, or anti–phospho-rpS6 (Ser 235/236) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for the appropriate loading controls. (B) The relative fold increase in phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments plus or minus SD.

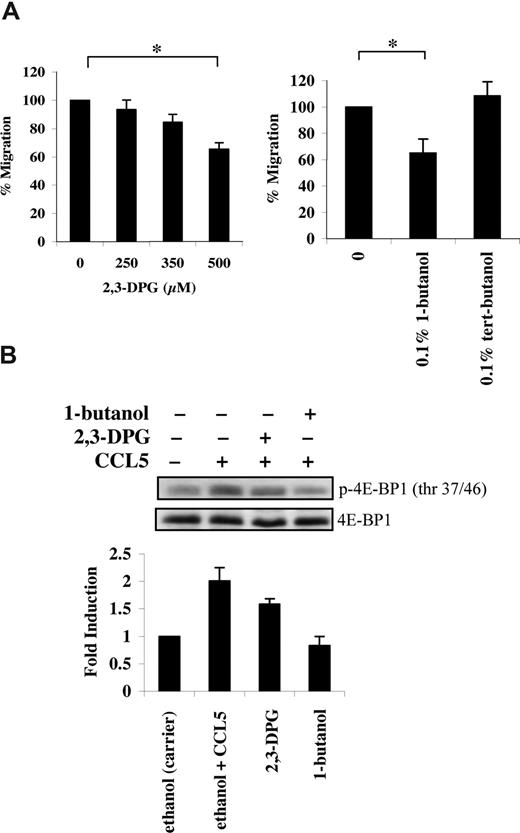

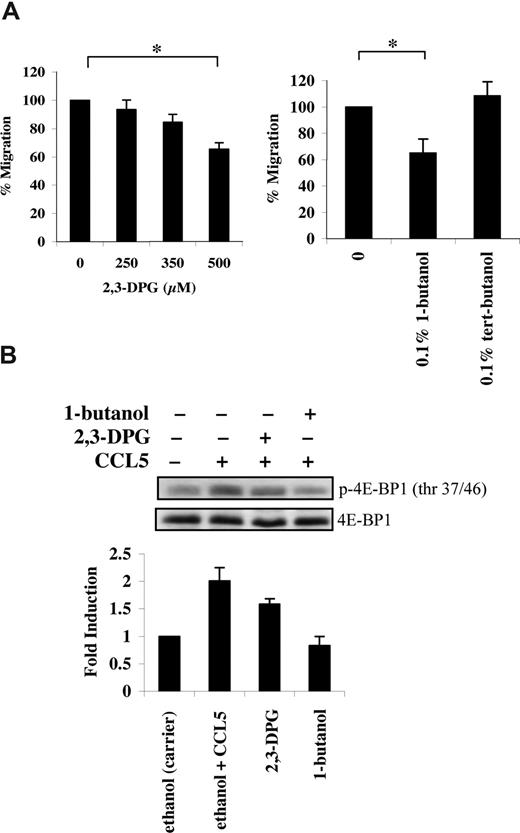

CCL5-mediated 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is PI-3′K, PLD, and mTOR dependent

mTOR has an additional role in phosphorylating the mRNA translational repressor 4E-BP1. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 is sequential, since phosphorylation of threonine 37/46 appears to be required for threonine 70 and serine 65 phosphorylation.36 In PB T cells, CCL5 induced a rapid phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 on both threonine 37/46 and threonine 70 sites (Figure 3A). The roles of PI-3′K, PLD, and mTOR in CCL5-dependent 4E-BP1 phosphorylation on threonine 37/46 were determined using various inhibitors. Pretreatment of PB T cells with LY294002, rapamycin, or 1-butanol abolished 4E-BP1 phosphorylation. (Figures 3B,4B). Consistent with their inhibitory effects on 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, both PLD inhibitors 2,3-DPG and 1-butanol reduced CCL5-mediated migration of PB T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A). Notably, CCL3 did not induce phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 on threonine 37/46, consistent with our findings that rapamycin also does not affect CCL3-mediated T-cell migration (Figure S1B).

CCL5 phosphorylates the 4E-BP1 repressor of mRNA translation through PI-3′ kinase and mTOR. (A) Activated PB T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) antibody or anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 70) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for 4E-BP1 as a loading control. The relative fold increase of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control to the right of each blot. (B) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either DMSO (carrier), 20 μM LY294002, or 50 nM rapamycin for 1 hour prior to 15-minute treatment with 10 nM CCL5. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for 4E-BP1 as a loading control. The relative fold increase of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments plus or minus SD.

CCL5 phosphorylates the 4E-BP1 repressor of mRNA translation through PI-3′ kinase and mTOR. (A) Activated PB T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) antibody or anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 70) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for 4E-BP1 as a loading control. The relative fold increase of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control to the right of each blot. (B) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either DMSO (carrier), 20 μM LY294002, or 50 nM rapamycin for 1 hour prior to 15-minute treatment with 10 nM CCL5. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for 4E-BP1 as a loading control. The relative fold increase of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments plus or minus SD.

CCL5-mediated PLD activation regulates T-cell migration. (A) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either ethanol (carrier) or the specified inhibitors for 1 hour at the concentrations indicated, and CCL5-mediated chemotaxis was measured using 10 nM CCL5. The data are presented as percentage migration, with the number of migrated cells at 10 nM CCL5 taken as 100%. Data representative of 3 independent experiments are shown (± SD); *P < .05. (B) T cells were pretreated with either ethanol (carrier), 500 μM 2,3-DPG, or 0.1% 1-butanol for 1 hour prior to 15-minute treatment with 10 nM CCL5. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) antibody. Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti–4E-BP1 antibody as a loading control. The relative fold increase of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

CCL5-mediated PLD activation regulates T-cell migration. (A) Activated PB T cells were pretreated with either ethanol (carrier) or the specified inhibitors for 1 hour at the concentrations indicated, and CCL5-mediated chemotaxis was measured using 10 nM CCL5. The data are presented as percentage migration, with the number of migrated cells at 10 nM CCL5 taken as 100%. Data representative of 3 independent experiments are shown (± SD); *P < .05. (B) T cells were pretreated with either ethanol (carrier), 500 μM 2,3-DPG, or 0.1% 1-butanol for 1 hour prior to 15-minute treatment with 10 nM CCL5. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) antibody. Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti–4E-BP1 antibody as a loading control. The relative fold increase of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

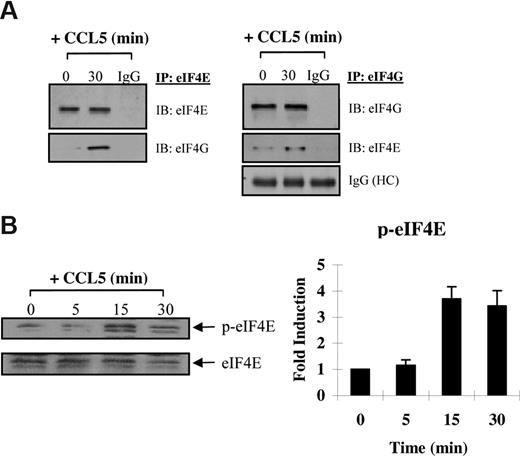

CCL5 initiates protein translation through formation of the eIF4F complex

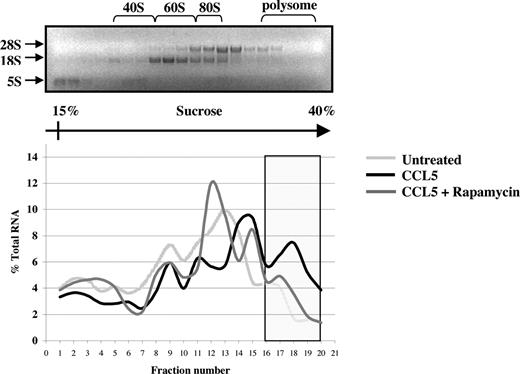

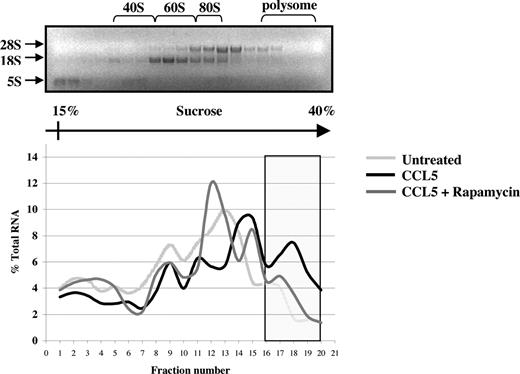

The preceding suggests that CCL5 may regulate eIF4E availability through mTOR-dependent phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Increased availability of eIF4E allows for the formation of the eIF4F complex, which also includes eIF4G, a multidomain scaffold protein, and eIF4A, a RNA helicase that is required to unwind regions of the secondary structure in the 5′-UTRs of mRNAs.48,49 To determine whether CCL5 mediates the formation of the eIF4F complex, cells were treated with CCL5 for 30 minutes and cell lysates immunoprecipiated for eIF4E and eIF4G. As shown in Figure 5A, CCL5 induced an association between eIF4E and eIF4G. To examine the phosphorylation status of eIF4E, cells were treated with 10 nM CCL5 and the cell lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis. As shown in Figure 5B, CCL5 induced phosphorylation of eIF4E on serine 209 after 15 minutes that was sustained for up to 60 minutes (data not shown). To directly show increased mRNA translation, sucrose gradient centrifugation was performed. Cells were treated with CCL5 for 1 hour and RNAs from each fraction extracted and analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel to examine polysome integrity. The distribution of 28S, 18S, and 5S rRNA in untreated cells was visualized by ethidium bromide staining (Figure 6 top panel). CCL5 initiated active translation of mRNA, as shown by the increased presence of high-molecular-weight polysomes deep in the sucrose gradient (fractions 16-20; Figure 6 bottom panel). Pretreatment with rapamycin inhibited the formation of heavy polysomes. Viewed all together, these data show that CCL5 promotes an mTOR-dependent active translation of mRNA by the eIF4F translation initiation complex.

CCL5 induces formation of the eIF4F initiation complex. (A) Activated PB T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for 30 minutes, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with either anti-eIF4E or anti-eIF4G antibodies. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-eIF4E and anti-eIF4G antibody. Whole molecule mouse or rabbit IgG was used as control. (B) Cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times; then lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-eIF4E (Ser 209) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for eIF4E as a loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments plus or minus SD. Values denoting the extent of phosphorylation are shown in the right-hand panel.

CCL5 induces formation of the eIF4F initiation complex. (A) Activated PB T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for 30 minutes, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with either anti-eIF4E or anti-eIF4G antibodies. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-eIF4E and anti-eIF4G antibody. Whole molecule mouse or rabbit IgG was used as control. (B) Cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times; then lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–phospho-eIF4E (Ser 209) antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for eIF4E as a loading control. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments plus or minus SD. Values denoting the extent of phosphorylation are shown in the right-hand panel.

CCL5-inducible protein translation enhances mRNA association with polyribosomes. PB T cells were pretreated with either DMSO (carrier) or 50 nM rapamycin for 1 hour, followed by 10 nM CCL5 for 1 hour. Cells were harvested and lysed, and lysates were layered onto a sucrose gradient. Fractions were collected after centrifugation, and RNAs were extracted and quantified at optical density (OD) 254 nm. A representative gel profile of fractions from untreated cells is shown to visualize the distribution of 5S, 18S, and 28S rRNAs as an indicator of the polyribosome integrity (top panel). OD readings for each fraction were plotted as a percentage of the total RNA of all fractions and are shown as a function of gradient depth (bottom panel). Actively translated mRNA is associated with high-molecular-weight polysomes deep in the gradient (shaded region). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

CCL5-inducible protein translation enhances mRNA association with polyribosomes. PB T cells were pretreated with either DMSO (carrier) or 50 nM rapamycin for 1 hour, followed by 10 nM CCL5 for 1 hour. Cells were harvested and lysed, and lysates were layered onto a sucrose gradient. Fractions were collected after centrifugation, and RNAs were extracted and quantified at optical density (OD) 254 nm. A representative gel profile of fractions from untreated cells is shown to visualize the distribution of 5S, 18S, and 28S rRNAs as an indicator of the polyribosome integrity (top panel). OD readings for each fraction were plotted as a percentage of the total RNA of all fractions and are shown as a function of gradient depth (bottom panel). Actively translated mRNA is associated with high-molecular-weight polysomes deep in the gradient (shaded region). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

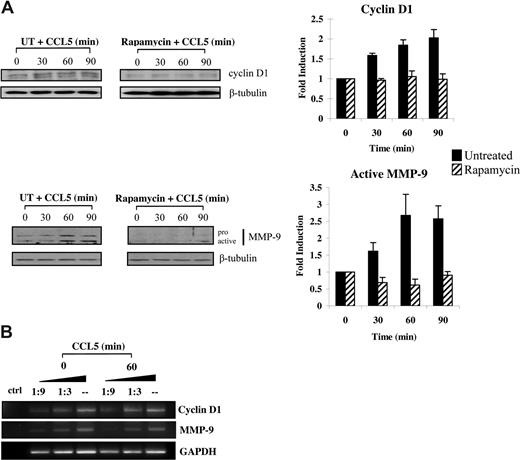

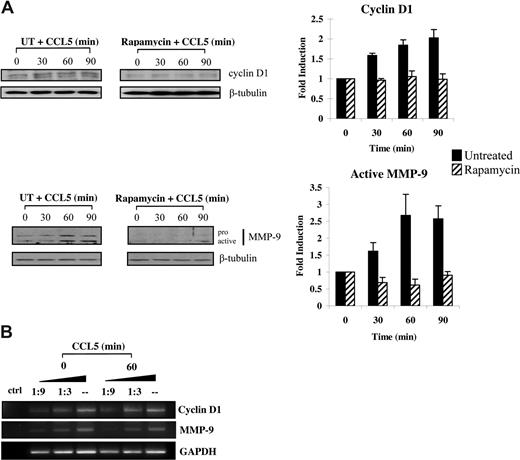

CCL5-inducible protein translation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 is mTOR dependent

Increased eIF4E availability leads to translation initiation of a subset of mRNAs with substantial secondary structures in the 5′-UTR.57 Among these, both MMP-9 and cyclin D1 have recently been shown to promote cellular motility.58-63 Accordingly, we conducted studies to examine whether CCL5 initiated the translation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 levels. Serum-starved T cells were pretreated with either DMSO or rapamycin for 1 hour and treated with 10 nM CCL5 in time course experiments. CCL5 induced up-regulation of both cyclin D1 and MMP-9 protein levels within 60 minutes, whereas rapamycin completely abolished this induction (Figure 7A). The observed increases in cyclin D1, and MMP-9 protein levels were not due to increased mRNA transcription, as their mRNA levels remained unchanged (Figure 7B).

CCL5-inducible up-regulation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 protein levels is dependent on mTOR-mediated mRNA translation. (A) Activated PB T cells were either pretreated with DMSO (carrier) or 50 nM rapamycin for 1 hour prior to treatment with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–cyclin D1 or anti–MMP-9 antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin as loading control. The relative fold increase of cyclin D1 protein level is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD. (B) T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for 1 hour and the mRNAs extracted. Semiquantitative RT-PCRs were performed using primer sets specific for cyclin D1, MMP-9, and GAPDH, as described in “Methods.” Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

CCL5-inducible up-regulation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 protein levels is dependent on mTOR-mediated mRNA translation. (A) Activated PB T cells were either pretreated with DMSO (carrier) or 50 nM rapamycin for 1 hour prior to treatment with 10 nM CCL5 for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–cyclin D1 or anti–MMP-9 antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin as loading control. The relative fold increase of cyclin D1 protein level is shown as signal intensity over loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD. (B) T cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM CCL5 for 1 hour and the mRNAs extracted. Semiquantitative RT-PCRs were performed using primer sets specific for cyclin D1, MMP-9, and GAPDH, as described in “Methods.” Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

Chemokines play a crucial role in directing leukocyte migration toward sites of inflammation during an immune response. Considerable advances have been made toward understanding the complex signaling cascades coordinating cell migration, which include the activation of many distinct tyrosine kinases, lipid kinases, and MAPKs. However, the contribution of mTOR-dependent mRNA translation to chemotaxis has not been studied. Initial observations with cycloheximide and actinomycin D, inhibitors of mRNA translation and transcription, respectively, demonstrated the importance of mRNA translation for CCL5-mediated human T-cell chemotaxis.

We have demonstrated that CCL5-mediated migration of activated CD4+ T cells is partially dependent on mTOR. Once activated, mTOR regulates the translational machinery by directly affecting eIF4F availability for 5′-capped mRNA translation initiation and up-regulates ribosomal protein levels through 5′-TOP mRNA translation. Published reports suggest a role for both mTOR and p70 S6K1 in cellular migration of various cell types. GM-CSF–mediated neutrophil chemotaxis is inhibited by rapamycin, wherein phosphorylation of S6K1 is associated with migration.32,64 Similarly, fibronectin-induced migration of human arterial E47 smooth muscle cells is sensitive to rapamycin.31 Several chemokines have been reported to activate S6K1, but this activation was studied in the context of cell survival and proliferation, not migration.65-68 Interestingly, a G protein–coupled receptor (vGPCR), which belongs to the CXC chemokine receptor family, is encoded by the Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV or human herpesvirus 8 [HHV8]) and exhibits constitutive activity. Ectopic expression and activation induced the TSC2/mTOR pathway, which played a critical role in Kaposi sarcomagenesis by promoting cell growth.69,70 Here, we show the importance of mTOR in CCL5-CCR5–mediated CD4+ T-cell chemotaxis. CCL5 induces rapid phosphorylation/activation of mTOR and S6K1. Several downstream effectors of S6K1 have been identified including rpS6, eIF4B, and eEF2.41,50 S6K1 activation favorably promotes translation by directly phosphorylating eIF4B to assist eIF4A helicase in unwinding RNA secondary structure.71 The role for rpS6 is less well understood, previously believed to be associated with 5′-TOP mRNA translation. However, studies with knock-in mice in which all 5 regulated sites of S6 phosphorylation were altered to alanines (S6[5A]) demonstrated that rpS6 is not required for 5′-TOP mRNA translation, but rather for controlling cell size.52 Nevertheless, phosphorylation of rpS6 remains an important readout for S6K1 activity.

mTOR also phosphorylates the mRNA translational repressor, 4E-BP1, in a sequential manner.56,72 mTOR phosphorylates threonine 37/46, followed by phosphorylation of threonine 70 and serine 65, ultimately leading to its release from eIF4E. Here we show CCL5 mediates a rapid phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 on both threonine 37/46 and threonine 70 sites. Phosphorylation of threonine 37/46 is dependent on PI-3′K, PLD, and mTOR. Therefore, the data indicate that CCL5-mediated activation of the PI-3′K and PLD signaling pathways may converge at the level of mTOR to modulate downstream 4E-BP1 phosphorylation. 4E-BP1 hyperphosphorylation releases eIF4E to allow for association with the scaffold protein eIF4G, which along with the RNA helicase eIF4A, forms the eIF4F heterotrimeric initiation complex.48,49 By binding to the 5′-cap structure of mRNA through eIF4E, the eIF4F initiation complex facilitates ribosome binding and its passage along the 5′-UTR toward the initiation codon. eIF4E is also directly phosphorylated on serine 209 by Mnk1/2, although the physiological relevance is still unclear. Several reports demonstrated that phosphorylated eIF4E actually had reduced m7G cap-binding ability.73,74 Proud suggested that phosphorylation of eIF4E may allow the eIF4F complex to detach from the 5′-cap during scanning to either accelerate translation or to allow a second initiation complex to bind the mRNA.41 Our data support this model, as phosphorylation of eIF4E was not evident until 15 minutes after CCL5 treatment (Figure 5B). This allows time for eIF4E to bind the cap structure and recruit eIF4G/eIF4A and other associated factors such as eIF3 and the 40S subunit before the complex is released for scanning. Consistent with this, CCL5 initiated active translation of mRNA, as shown by increased presence of high-molecular-weight polysomes deep in the sucrose gradient we analyzed (fractions 16-20). The presence of polysomes was significantly reduced in the presence of rapamycin, further supporting the role for mTOR in translation initiation.

It is well known that cap structures at the 5′ end of mRNA are required for efficient translation, nuclear export, and protection from 5′ exonucleases. Once bound by eIF4F, ribosome binding and scanning can commence along the 5′-UTR toward the initiation codon. Unlike mRNAs with short 5′-UTRs (eg, β-actin), a subset of mRNAs with lengthy, highly structured 5′-UTRs is poorly translated when eIF4F levels are low.57,75 Among these, cyclin D1 and MMP-9 have been implicated in cellular migration of a number of cell types.33,59-63 Li et al showed that cyclin D1–deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) exhibited increased adhesion and decreased motility compared with wild-type MEFs.61 Migratory defects in cyclin D1–deficient MEFs were not a direct consequence of reduced DNA synthesis, but rather through derepression of ROCKII and TSP-1 expression. Use of PI-3′K and mTOR inhibitors in cancer cell lines decreased cyclin D1 levels, where eIF4E overexpression led to its increased production.76-79 IL-8 has been shown to up-regulate cyclin D1 at the level of translation in prostate cancer cell lines.80 Similarly, in MMP-9 knockout mice, bone marrow–derived dendritic cell (BM-DC) migration to CCL19 was impaired, and anti–MMP-9 antibody reduced CCL5-mediated migration of IFNα DCs.60 Therefore, we investigated the ability of CCL5 to initiate translation of both cyclin D1 and MMP-9 in T cells. Rapamycin-sensitive up-regulation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 protein levels occurred within 1 hour of CCL5 treatment. Up-regulation of protein levels was not due to increased transcription since we did not observe significant mRNA synthesis of these genes within this time frame. Interestingly, others have shown that CCL5-mediated increases in MMP-9 protein levels are detectable early without significant up-regulation of mRNA, indicating that the early effect of CCL5 on MMP-9 secretion was independent of mRNA synthesis.81 Since T-cell chemotactic migration through a model basement membrane depends on the degradation of matrix proteins by MMP-9, rapid production of the protease during the early stages of cellular migration is critical in vivo.58

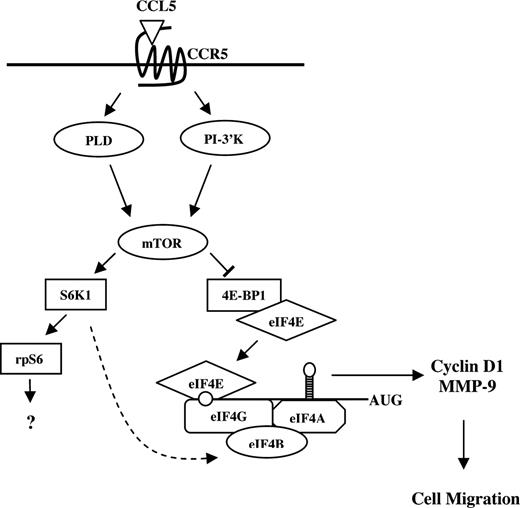

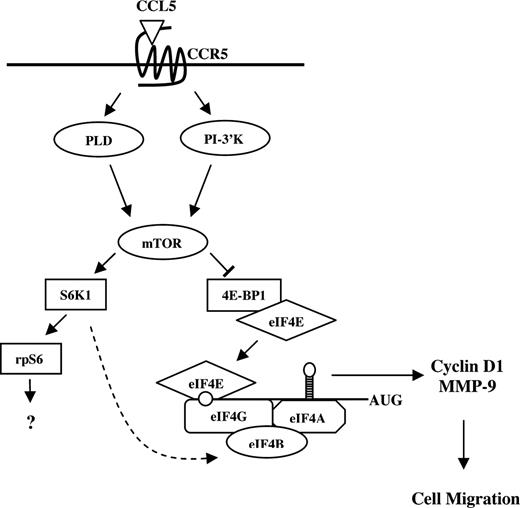

Gomez-Mouton et al used real-time microscopy to elegantly demonstrate that CCR5-positive Jurkat T cells respond to CCL5 almost instantaneously, forming a leading edge and directional migration toward the source of chemokine.82 In a typical chemotaxis assay, migrated cells are collected and counted after 2 hours of incubation, but as demonstrated by real-time microscopy, T cells likely do not take 2 hours to migrate through the membrane pores. We have unpublished data (T.T.M., August 2007) demonstrating that rapamycin does not affect CCL5-mediated actin polymerization, indicating that mTOR plays no role in the initial stages of migration. Rather, CCL5-mediated translation initiation may contribute to the rapid synthesis of chemotaxis-related proteins to “prime” T cells for effective directed migration (Figure 8). CCR5 is the receptor for several chemokines, specifically CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5. We observe that CCL3 and CCL5 differentially activate mTOR signaling. mTOR and mTOR-mediated signaling seem to be dispensable for CCL3-mediated T-cell chemotaxis. Notably, CCL3-CCR5–mediated chemotaxis of T cells is considerably less effective than CCL5-CCR5–mediated T-cell chemotaxis. It is intriguing to speculate that CCR5-indicible activation of mTOR signaling may contribute to this differential potency. The identification of additional proteins that are regulated by CCL5 at the level of translation is currently under investigation. Translational control generates a rapid production of proteins without the need for mRNA transcription, processing, and export into the cytoplasm. As migratory responses must be both initiated and resolved with speed and precision, it is beneficial that chemokines can effect translation and rapidly influence the protein pool within the migrating cell. Our data describe a novel mechanism by which the chemokine CCL5 may regulate translation of mRNAs that encode proteins involved in T-cell migration, such as cyclin D1 and MMP-9. In addition, our data suggest a mechanism for the immunosuppressive effects of rapamycin, possibly by limiting host immune cell migration.

Possible model for CCL5-mediated mRNA translation in CD4+ T cells. CCL5 activates the mTOR pathway and subsequent phosphorylation of p70 S6K1 and 4E-BP1. Hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 leads to its release from eIF4E where it binds to eIF4G to form the eIF4F initiation complex. Through eIF4E, eIF4F binds to the mRNA 5′-cap structure and facilitates ribosome binding and unwinding secondary structure in the 5′-UTR. Translation initiation leads to a rapid up-regulation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 protein levels to “prime” T cells for directed cell migration. S6K1 has been shown to phosphorylate eIF4B (RNA-binding protein that enhances activity of the eIF4A helicase) in response to insulin ( ).

).

Possible model for CCL5-mediated mRNA translation in CD4+ T cells. CCL5 activates the mTOR pathway and subsequent phosphorylation of p70 S6K1 and 4E-BP1. Hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 leads to its release from eIF4E where it binds to eIF4G to form the eIF4F initiation complex. Through eIF4E, eIF4F binds to the mRNA 5′-cap structure and facilitates ribosome binding and unwinding secondary structure in the 5′-UTR. Translation initiation leads to a rapid up-regulation of cyclin D1 and MMP-9 protein levels to “prime” T cells for directed cell migration. S6K1 has been shown to phosphorylate eIF4B (RNA-binding protein that enhances activity of the eIF4A helicase) in response to insulin ( ).

).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Carole Galligan and Cole Stanley for excellent scientific discussions and technical assistance.

These studies were supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant no. 278397. T.T.M. and R.R. were supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) doctorate award. L.C.P. was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA77816 and CA121192 and by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: T.T.M. performed research and drafted the paper; R.R. analyzed and interpreted data; L.C.P. designed and analyzed data; E.N.F. designed research, analyzed data, and drafted the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: E. N. Fish, Division of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Toronto General Research Institute, Canadian Blood Services Bldg, 67, College St, Rm 4-424, Toronto, ON M5G 2M1, Canada; e-mail: en.fish@utoronto.ca.

).

).