In this issue of Blood, Winston and colleagues show that the prophylactic administration of maribavir, an oral inhibitor of the CMV UL97 kinase, reduces CMV infection (reactivation or viremia) by more than 50% after allogeneic HSCT.

I remember cytomegalovirus (CMV) as a scourge that competed with relapse as the top cause of death after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Although ganciclovir eliminated CMV as a significant cause of mortality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), neutropenia associated with its prolonged administration—whether prophylactic (before infection) or preemptive (after infection, but before the development of CMV disease)—increased bacterial and fungal infections, thereby blunting its beneficial impact on survival.1-3 Prolonged ganciclovir administration also delayed reconstitution of CMV-specific cell-mediated immunity, contributing to late infections after therapy was discontinued. However, a short 3-week course of preemptive ganciclovir was found to be effective in treating cytomegaloviremia without increasing other infections or causing frequent episodes of repeat viremia.4 Such preemptive short-course ganciclovir therapy (or its oral prodrug, valganciclovir) has become the gold-standard approach to CMV infection, and arguably is one of the few factors to have improved survival after allogeneic SCT over the last 15 years.5

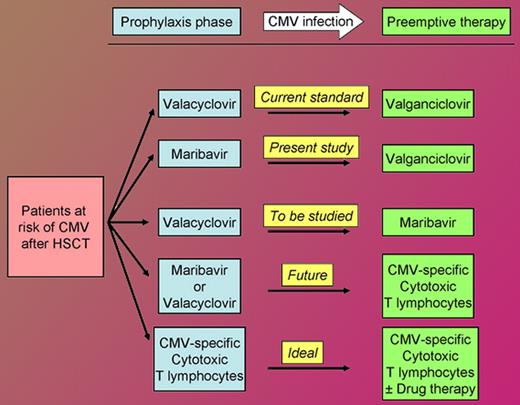

The present study explores the prolonged use of maribavir to prevent CMV infection. However, because maribavir is also effective in treating CMV infection,6 an approach worth exploring is the use of maribavir for preemptive treatment of CMV infection and the use of valacyclovir for prophylaxis. This approach is attractive because valacyclovir, while reducing CMV infection to some extent, effectively suppresses H simplex and V zoster reactivation, viruses against which maribavir is inactive.

Although maribavir did not suppress marrow function or cause nephrotoxicity in this study, it did cause dysgeusia and nausea. These side effects may be of concern in a setting where adequate nutrition is a challenge, and poor compliance with other oral medications such as immunosuppressive and anti-microbial agents may affect outcome adversely. Will prolonged exposure to maribavir also prevent reconstitution of CMV-specific cell-mediated immunity? Will maribavir improve survival? What is the best way to use maribavir? These are important questions that need to be answered, in part by ongoing studies.

The mechanism of action of maribavir differs from the other drugs active against CMV available today (ganciclovir/valganciclovir, foscarnet, cidofovir, and fomivirsen—the last one for ophthalmic use only). Despite similar mechanisms of action, there is evidence to suggest that each of these drugs is effective in some instances of failure of one or more of the others. Additionally, CMV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes have been used to reconstitute immunity after HSCT to prevent and treat CMV infection.7

As the figure shows, the availability of maribavir will increase options for the management of the allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient at risk of CMV infection, today and in the future. Nearly 17 years after I helplessly saw my first patient die of CMV, the multiple drugs and adoptive cell therapy active against CMV have practically “rid me of this turbulent” pest as a major concern after HSCT.

Approach to the allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient at risk of cytomegalovirus infection. This does not cover prophylaxis against Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster virus infections against which valacyclovir is active but maribavir is not.

Approach to the allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient at risk of cytomegalovirus infection. This does not cover prophylaxis against Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster virus infections against which valacyclovir is active but maribavir is not.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Northwestern University is a participant in the ongoing randomized, double-blind study of maribavir in allogeneic HSCT with the author as the local principal investigator. ■