Abstract

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) may be associated with mutations in the C-terminal of factor H (FH). FH binds to platelets via the C-terminal as previously shown using a construct consisting of short consensus repeats (SCRs) 15 to 20. A total of 4 FH mutations, in SCR15 (C870R) and SCR20 (V1168E, E1198K, and E1198Stop) in patients with aHUS, were studied regarding their ability to allow complement activation on platelet surfaces. Purified FH-E1198Stop mutant exhibited reduced binding to normal washed platelets compared with normal FH, detected by flow cytometry. Washed platelets taken from the 4 patients with aHUS during remission exhibited C3 and C9 deposition, as well as CD40-ligand (CD40L) expression indicating platelet activation. Combining patient serum/plasma with normal washed platelets led to C3 and C9 deposition, CD40L and CD62P expression, aggregate formation, and generation of tissue factor-expressing microparticles. Complement deposition and platelet activation were reduced when normal FH was preincubated with platelets and were minimal when using normal serum. The purified FH-E1198Stop mutant added to FH-deficient plasma (complemented with C3) allowed considerable C3 deposition on washed platelets, in comparison to normal FH. In summary, mutated FH enables complement activation on the surface of platelets and their activation, which may contribute to the development of thrombocytopenia in aHUS.

Introduction

Complement activation is regulated on cell surfaces by a combination of several cellular and fluid phase regulators. Platelets express membrane-bound complement regulators CD46, CD55,1,2 and CD59.3 Platelets and megakaryocytes also contain factor H (FH),4,5 the main fluid-phase regulator of the alternative pathway. FH is predominantly produced in the liver6 and exhibits activity both in the fluid phase and on the cell surface. It circulates as a 150-kDa protein at a concentration of approximately 500 μg/mL and acts as a cofactor for cleavage of C3b by factor I.7 In addition, it binds to C3b, preventing binding of factor B to the C3Bb convertase.8 FH consists of 20 short consensus repeats (SCRs).9 The complement regulatory region in the N terminus displays cofactor activity and decay-accelerating activity and the C-terminal cell-binding region mediates host recognition by interacting with heparin, glucosaminoglycans, C3b, and endothelial cells.10,11 We have previously shown that FH binds to washed platelets via the C terminus.12 FH mutations have been identified in a subset of patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). The patients are usually heterozygous for the mutations, of which most are located at the C terminus of the protein, mostly in SCR 20.13 HUS is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure.14 HUS has been classified as typical when associated with a diarrheal prodrome and Shiga toxin–producing bacteria or atypical (aHUS) (ie, not associated with Shiga toxin–producing bacteria) in which a subset is associated with disorders of complement regulation,15 including dysfunctional FH due to mutations or autoantibodies,16-19 as well as mutations in factor I,20,21 CD46/membrane-cofactor protein,22,23 and factor B.24

In Shiga toxin–associated HUS, platelets are activated, leading to their consumption in microthrombi. The mechanism may be related to toxin-mediated endothelial cell injury25 as well as direct platelet activation by Shiga toxin26 and other bacterial virulence factors such as lipopolysaccharide.27 The mechanisms of platelet activation leading to thrombocytopenia in atypical HUS have, as yet, not been elucidated. Defective binding of FH to endothelial cells28 may reduce its capability to protect host cells from complement activation,29 leading to exposure of the subendothelium during endothelial cell injury. This may result in both complement deposition30 and a prothrombotic state secondary to exposure of collagen, von Willebrand factor, and fibrinogen in the subendothelium,31 which may enhance local platelet aggregation.32 Similarly, dysfunctional complement regulation on the platelet surface could be expected to lead to complement deposition and a prothrombotic state. Complement deposition has been shown to trigger platelet activation as well as the generation of the membrane attack complex, leading to lysis.33,34 Deposition of C3 on platelets in conditions such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)35 and during cardiopulmonary bypass was suggested to promote their activation,36,37 leading to reduced platelet counts. During platelet aggregation, procoagulant vesicles are shed. These platelet-derived microparticles (PMPs) express negatively charged phospholipids, which provide a procoagulant surface for assembly of clotting enzymes,38 and recent data identified PMPs as the main source of functionally active tissue factor (TF), the major initiator of coagulation in vivo.39

The purpose of this study was to investigate if FH mutations in aHUS cause dysfunction that enables complement deposition on the surface of platelets, resulting in their activation. Studying 4 different aHUS-related mutations in SCRs 15 and 20, we examined if patient sera and purified FH from one patient enabled complement deposition on platelets, leading to their activation.

Methods

Patients, their parents, and controls

A total of 4 patients with aHUS associated with FH mutations were included in this study as presented in Table 1.

Patient 1 is a 35-year-old female patient treated at the Department of Internal Medicine, Halmstad Regional Hospital (Sweden). The patient underwent an operation for endometriosis, has taken oral contraceptives, and has gone through one successful pregnancy. At 30 years of age, while on oral contraceptives, she was admitted for malaise, fever, nausea, icterus, and hematuria. Laboratory testing indicated hemolytic anemia with helmet cells, thrombocytopenia, increased lactic dehydrogenase, and azotemia. The patient has, since the first episode, had 3 recurrences of HUS leading to reduced renal function (glomerular filtration rate, 28 mL/min). C3 levels have been slightly lower than the normal range (Table 1), and FH has been normal to slightly elevated (84% and 155%; normal range, 69%-154%). A normal FH band at 150 kDa was detected in patient serum by immunoblotting.5 She is currently treated with prophylactic plasma exchange every 14 days. Blood samples were available at different time points (serum, n = 3; platelets, n = 2) taken just before plasma exchange.

Patient 2 is a previously described 9-year-old girl with a de novo mutation in FH5 treated at the Department of Nephrology of Southwest Texas Methodist Hospital, San Antonio. She is currently treated with hemodialysis. FH levels in her serum samples were normal, and a band was detected at 150 kDa.5 Blood samples were available at different time points (serum, n = 2; platelets, n = 2).

Patient 3 is a 27-year-old female patient treated at the Department of Renal Medicine, Huddinge University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden). At 20 years of age, while on oral contraceptives, she was admitted for nausea and edema. Laboratory values indicated hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, azotemia, and elevated creatinine and lactic dehydrogenase levels. She was treated with hemodialysis until December 2006, when she underwent cadaveric renal transplantation. FH and C3 levels were reduced before transplantation (Table 1), and a 150-kDa FH band was detected by immunoblotting. The patient had one recurrence 5 months after transplantation, which was treated successfully with plasma exchange. Blood samples were available from different occasions (serum, n = 3 before transplantation and n = 1 after transplantation; platelets, n = 1 after transplantation; samples taken after transplantation were obtained before the recurrence).

Patient 4 is a previously described 5-year-old boy44 currently treated at Children's University Hospital (Tübingen, Germany) with peritoneal dialysis. C3 and FH levels were normal (Table 1), but immunoblotting detected a double band at 150 kDa and slightly below. Blood samples were available from 3 time points (serum, n = 3; platelets, n = 1).

All 4 patients had normal platelet counts at sampling and normal ADAMTS13 activity tested using a modified collagen-binding assay.45 Serum was also available from all the patients' parents. At the time of sampling, the father of patient 1 was being treated for lymphosarcoma. Blood was further obtained from 15 healthy adult controls (6 men, 9 women) not using medications. Plasma was in addition available from a previously described5 deceased male patient treated at the Department of Renal Medicine, Huddinge University Hospital, for aHUS and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with a homozygous FH mutation in exon 13 (P621T). The plasma sample exhibited FH and C3 deficiency.5 Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from patients, their parents, and controls. Samples were taken with the approval of the Ethics Committees of Lund and Stockholm Universities.

Blood samples and washed platelets

Whole blood was drawn by venipuncture into vacutainer tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K2EDTA; 1.8 mg/mL; Becton Dickinson). Platelet-rich plasma was obtained by centrifugation of whole blood at 200g for 20 minutes. Platelet rich plasma was removed, diluted 1:1 in EDTA buffer (0.9 mM EDTA, 0.26 mM Na2HPO4(H2O), and 0.14 M NaCl [pH 7.2])26 and further centrifuged at 2000g for 10 minutes. Platelets were washed in EDTA buffer and resuspended in Tyrode buffer.46

Washed platelets were also obtained from whole blood drawn by venipuncture via a butterfly needle (Plasti Medical, Villamarzana, Italy). The first 2 mL were discarded, and the remainder was collected into 2.7-mL plastic tubes containing 0.109 M sodium citrate (Becton Dickinson). Platelets were washed and resuspended as described. The final concentration of washed platelets in all experiments was 108/mL. Citrated platelet-poor plasma was obtained by centrifugation of whole blood at 2000g for 10 minutes.

Serum was obtained by allowing freshly drawn blood in BD vacutainer serum tubes (Becton Dickinson) to clot for 1 hour at room temperature. Sera was separated from the clot by centrifugation at 3500g for 10 minutes and stored in aliquots at −80°C until used.

Isolation of DNA and sequencing of FH

FH function assayed by hemolysis of sheep erythrocytes

FH function was determined according to a previously described method.5,41 A total of 20 μL of serum were added to 80 μL of AP-CFTD buffer (2.5 mM barbital, 1.5 mM sodium barbital, 144 mM NaCl, 7 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM EGTA [pH 7.2–7.4]). A total of 100 μL of sheep erythrocytes (108 erythrocytes/mL) were added to each sample and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle agitation. In certain tubes normal FH (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was added at a final concentration of 25 μg/mL to patient serum. To stop the reaction, 1 mL ice-cold veronal-buffered saline with 2 mM EDTA was added. Samples were centrifuged, the absorbance of the supernatant was determined at 414 nm, and the percentage of lysis calculated.

Purification of mutant FH

FH was purified from the serum of the mother of patient 4, who has the same heterozygous FH mutation (E1198Stop) and polymorphism (C-257T) as the patient. FH purification was carried out as previously described.29 The mutant variant of FH (FH-E1198Stop) was purified by heparin affinity chromatography, ion exchange chromatography, and size exclusion chromatography, and thus separated from the normal FH.

Incubation of washed platelets with normal and mutated FH or serum

Washed platelets from sodium citrate tubes were incubated with or without 200 μg/mL normal FH (Calbiochem) or FH-E1198Stop for 30 minutes at 37°C. Alternatively, the platelets were incubated with an equal volume of serum at room temperature. The reaction was stopped after 2 minutes by addition of 1:10 (vol/vol) EDTA buffer followed by centrifugation and fixation with 0.5% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Fixation occurred within 2 hours of sampling. In certain experiments, washed platelets were incubated simultaneously with serum and thrombin (1 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich)12 or preincubated with FH (Calbiochem) at a final concentration of 200 μg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or with PBS alone, for 30 minutes at 37°C before addition of serum with or without thrombin.

In one set of experiments, washed platelets were preincubated with normal FH (Calbiochem; final concentration, 200 μg/mL) or the mutant variant FH-E1198Stop mutant, at the same concentration, or a combination of normal FH and FH-E1198Stop mutant (100 μg/mL of each) for 30 minutes at 37°C. These platelets were further incubated with an equal volume of FH- and C3-deficient citrated plasma (from the male patient with the P621T mutation) with and without addition of purified C3 (400 μg/mL final concentration; Quidel, San Diego, CA). The reaction was stopped by addition of ice-cold EDTA buffer, and platelets were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Generation and isolation of PMPs

Sera (500 μL) were centrifuged for 45 minutes at 20 800g at room temperature. A total of 450 μL of the supernatant were filtered using a 0.2-μm (Schleicher-Schuell, Dassel, Germany) filter to remove preexisting PMPs. Likewise, all buffers used for generation of PMPs were prefiltered.

Washed platelets were incubated with an equal volume of serum for 2 minutes. Samples were then diluted (1:10) in TBS/BSA (50 mM Tris, 120 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin [BSA; pH 7.4]; ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) and centrifuged at 2000g for 10 minutes to discard the platelets. The sample was further centrifuged twice at 20 800g for 45 minutes and the supernatant was removed, resulting in a PMP-enriched suspension that was diluted in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 2.0 mM CaCl2, [pH 7.4]). In certain experiments, normal washed platelets were incubated with normal FH at a final concentration of 200 μg/mL, or with PBS, for 30 minutes at 37°C before addition of serum. Thrombin-activated washed platelets were used as the positive control.

Flow cytometric analysis

FH.

Washed platelets were incubated with 20 μg/mL IgG purified from human serum using Protein G sepharose (GE Healthcare, Stockholm, Sweden), as per the manufacturer's instructions, for 20 minutes on ice to prevent unspecific binding of the antibody, washed, and incubated with goat anti-human FH (0.5 μg/mL; Calbiochem) for 10 minutes on ice, or goat IgG (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, MA) as the control. Platelets were incubated for 10 minutes on ice with the secondary antibody rabbit anti–goat IgG:FITC (1:2000; Calbiochem).

C3.

C3 deposition on platelets was detected by incubation with chicken anti-human C3:FITC (1:700; Diapensia, Linköping, Sweden) for 10 minutes on ice. Chicken anti–human insulin:FITC (1:700; Diapensia) was used as the control antibody.

C9.

Washed platelets were first incubated with human IgG as for detection of FH, washed, and incubated for 10 minutes on ice with goat anti–human C9 (0.5 μg/mL, Advanced Research Technologies, San Diego, CA) or goat IgG (Oncogene Research Products) as the control. Rabbit anti-goat IgG:FITC (1:2000) was the secondary antibody.

CD40 ligand (CD40L) or P-selectin (CD62P).

Platelet activation47 was detected with rabbit anti–human CD40L (10 μg/mL; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or mouse anti–human CD62P:FITC (1:30; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). The control antibody was rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by swine anti–rabbit IgG:FITC (1:40; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) or mouse IgG1:FITC (BD Biosciences).

PMPs.

PMPs were diluted 1:4 in binding buffer and incubated for 20 minutes in the dark with annexin V:PE-Cy5 (1:20), mouse anti-human CD41a:FITC (1:40) and mouse anti–human tissue factor:PE (1:30), simultaneously, or isotype controls IgG1:FITC and IgG1:PE (all from BD Biosciences). Annexin V has high affinity and specificity for phosphatidylserine, and has shown to detect procoagulant activity of PMPs.48 For annexin V:PE-Cy5–positive events were subtracted from samples to which 0.1% EDTA (VWR, Stockholm, Sweden) was added as annexin V binding to membrane phosphatidylserine is inhibited in the absence of free calcium.

Acquisition and interpretation of flow cytometric data.

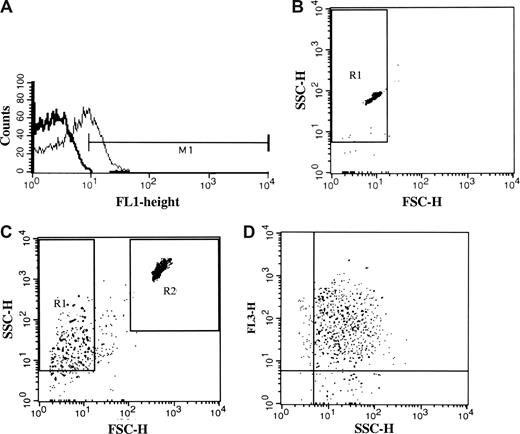

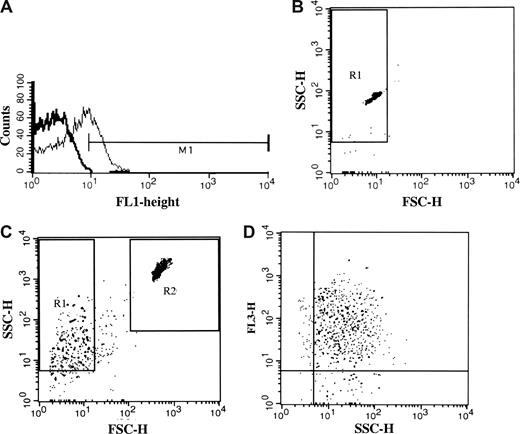

Platelets were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur cytometer and CellQuest Software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Platelets were identified on the basis of their forward scatter (FSC)–side scatter (SSC) profile. A gate was set around the platelet population and 10 000 events were analyzed for FITC fluorescence. In all experiments, binding was calculated after subtracting background fluorescence of the control antibody (Figure 1A) or in the case of annexin V:PE-Cy5 of samples with EDTA. Results are given as a percentage of positive events of the population. Specificity of the secondary antibody was defined by omission of the primary antibody.

Acquisition and interpretation of flow cytometric data. (A) Representative histogram showing binding of the C3 antibody (thin line) to 25% of the platelet population. M1 was determined by subtraction of the background fluorescence (thick line). Background signal from the control antibody was given an M1-value of approximately 1% in all experiments. (B) The PMP gate (R1) was determined in FSC and SSC by 0.8- to 1-μm fluorescent beads in buffer. (C) PMPs in the R1 gate were calculated in relation to the R2 gate consisting of 6μm non-fluorescent beads. Detection of events was terminated when 10 000 counts were obtained in the R2 gate. (D) Detection of phosphatidylserine-positive PMPs by annexin V:PE-Cy5 labeling in FL3 (y-axis) in relation to SSC (x-axis).

Acquisition and interpretation of flow cytometric data. (A) Representative histogram showing binding of the C3 antibody (thin line) to 25% of the platelet population. M1 was determined by subtraction of the background fluorescence (thick line). Background signal from the control antibody was given an M1-value of approximately 1% in all experiments. (B) The PMP gate (R1) was determined in FSC and SSC by 0.8- to 1-μm fluorescent beads in buffer. (C) PMPs in the R1 gate were calculated in relation to the R2 gate consisting of 6μm non-fluorescent beads. Detection of events was terminated when 10 000 counts were obtained in the R2 gate. (D) Detection of phosphatidylserine-positive PMPs by annexin V:PE-Cy5 labeling in FL3 (y-axis) in relation to SSC (x-axis).

PMPs were identified by size. The size of the gate (R1) was adjusted by 0.8- to 1-μm fluorescent microbeads (Sigma-Aldrich; Figure 1B), and threshold was set in the FSC parameter. PMPs were demonstrated in FSC in log scale (Figure 1C) as well as by the presence of annexin V (Figure 1D; FL3 vs SSC). All annexin V+ events sized 1 μm or smaller were considered to be PMPs.

For quantification of PMPs, a modification of the method of Shet et al was used,49 in which a known quantity (300 000) of nonfluorescent 6.0-μm beads (BD Biosciences) were added to each sample tube, and acquisition was terminated when 10 000 beads were counted. A positive event was defined as an event that exhibited higher fluorescent intensity than the isotype control. Results were expressed as the number of PMPs per milliliter of serum.

Immunofluorescence

Platelet aggregation in the presence of citrated plasma was detected by immunofluorescence on glass slides. After incubation of washed normal platelets with plasma for 30 minutes at 37°C, platelets were spun down on glass slides (Cytospin; Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA), fixed, blocked, and washed,27 and detection with mouse anti–human CD62:FITC was carried out as described.27 Thrombin-stimulated platelets were the positive control. Slides were examined under an Axiostar plus fluorescence microscope equipped with a 40×/0.07 objective lens and an Axiocam MRc5 camera (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). AxioVision AC software version 4.4 (Carl Zeiss) was used for image processing.

Statistics

Differences between platelets incubated with patient sera and control sera, with and without FH and/or thrombin, were assessed by the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value of .05 or lower was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 11 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

Results

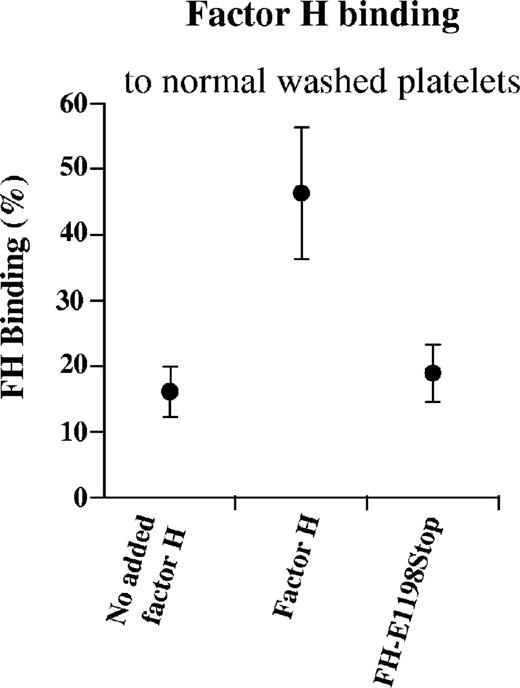

FH-E1198Stop mutant exhibits reduced binding to washed platelets

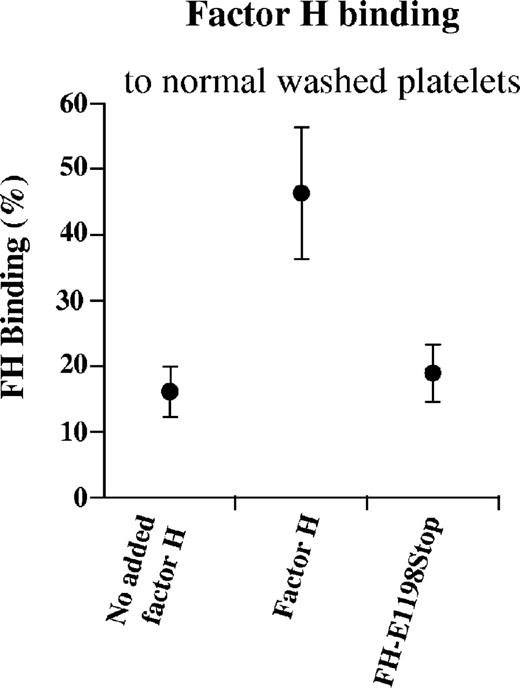

Washed platelets from healthy donors (n = 22) were studied with regard to the presence of FH. The population of normal washed platelets exhibited 16% FH binding on their surface (median; range, 12%-21%; Figure 2). This indicated that a subpopulation of normal platelets have detectable FH bound to their surface. When normal FH was added, bound FH increased to 47% (median; range, 35%-54%), but less so when the purified FH-E1198Stop mutant was added (median, 18%; range, 16%-22%), suggesting that the FH-E1198Stop mutant exhibits less binding to the platelet membrane than normal FH.

FH binding to normal washed platelets. FH on normal washed platelets (from citrated tubes) was detected by 16% binding (median; range, 12%-21%) of goat anti-human FH to the platelet population. When platelets were incubated with normal FH, additional binding was detected, but less so when the platelets were incubated with the FH-E1198Stop mutant. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

FH binding to normal washed platelets. FH on normal washed platelets (from citrated tubes) was detected by 16% binding (median; range, 12%-21%) of goat anti-human FH to the platelet population. When platelets were incubated with normal FH, additional binding was detected, but less so when the platelets were incubated with the FH-E1198Stop mutant. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

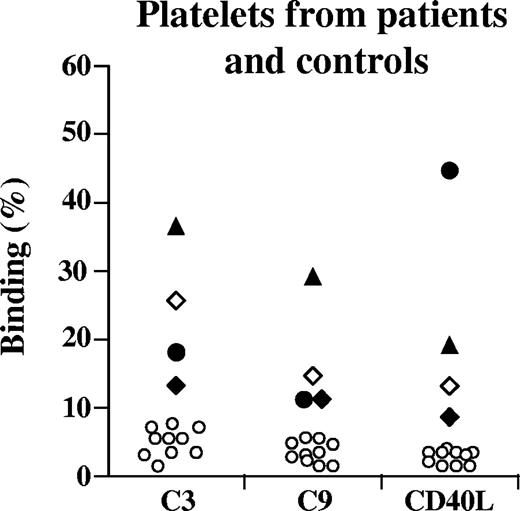

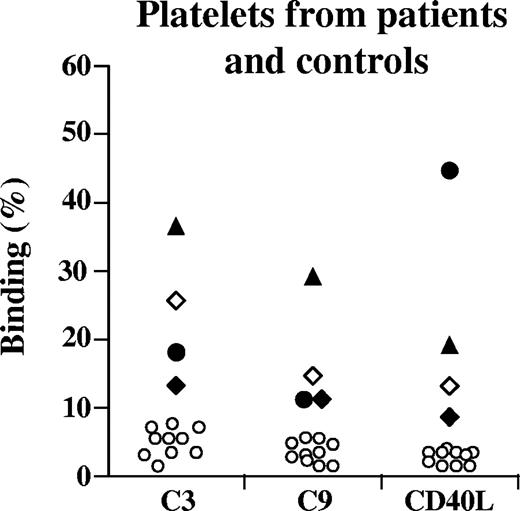

C3, C9, and CD40L on patient and normal washed platelets

Washed platelets from patients 1 through 4 displayed increased surface levels of C3, C9, and CD40L as shown in Figure 3. A minor reactivity for all 3 components was observed for washed platelets derived from healthy controls (n = 10) as shown in Figure 3.

Platelet-bound C3, C9, and CD40L. Washed platelets (from EDTA tubes) from patients 1 (♦), 2 (▴), 3 (●),4 (◇), or controls (○) were incubated with chicken anti-human C3 antibody, goat anti-human C9 antibody, or rabbit anti-human CD40L; binding was detected on patient platelets, but less on control platelets. No serum was added in these experiments. Results for patients 1 and 2 and controls (n = 10) were carried out twice with reproducible results. Results for patients 3 and 4 were carried out once.

Platelet-bound C3, C9, and CD40L. Washed platelets (from EDTA tubes) from patients 1 (♦), 2 (▴), 3 (●),4 (◇), or controls (○) were incubated with chicken anti-human C3 antibody, goat anti-human C9 antibody, or rabbit anti-human CD40L; binding was detected on patient platelets, but less on control platelets. No serum was added in these experiments. Results for patients 1 and 2 and controls (n = 10) were carried out twice with reproducible results. Results for patients 3 and 4 were carried out once.

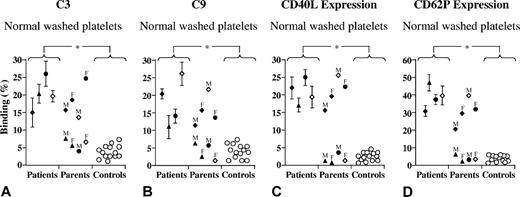

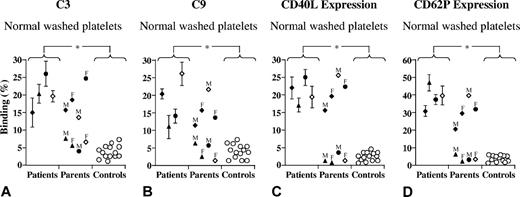

Serum from patients with aHUS mediates increased C3, C9 binding, and CD40L and CD62P expression

Addition of patient serum to normal washed platelets resulted in complement activation as indicated by C3 deposition (Figure 4A). In addition, sera obtained from the nonaffected parents of patients 1 through 4 was also investigated. When adding serum from the mother of patient 1, the father of patient 3, and the mother of patient 4 (all bearing the same mutation as the affected patient; Table 1), increased C3 was noted on normal platelets in comparison with control sera (Figure 4A). Serum from the father of patient 1, who did not have a factor H mutation (Table 1) but was being treated for lymphosarcoma, also showed increased C3 deposition. Similarly, C9, CD40L, and CD62P were detected on normal washed platelets exposed to patient serum, and serum from parents bearing the FH mutation, but not serum from healthy controls or the parents who did not bear the mutation, with the exception of the father of patient 1 (Figure 4B,C).

C3 and C9 binding and CD40L and CD62P expression on normal platelets exposed to serum. Washed normal platelets (from citrated tubes) were incubated with an equal volume (25 μL) serum from patients 1 (♦), 2 (▴), 3 (●), 4 (◇), parents, or controls (○). The patients' serum exhibited increased C3 and C9 binding to normal platelets compared with control sera. Likewise, patient sera resulted in increased CD40L and CD62P expression, suggesting activation. This was not seen when platelets were exposed to normal sera. Serum from the parent bearing the same mutation as the affected patient with aHUS exhibited similar results to the patients, whereas sera from the parents that did not bear the mutation resembled normal sera with the exception of the father of patient 1 (treated at the time of sampling for lymphosarcoma). Results for patients were carried out 3 times, and for the parents and controls twice with reproducible results. *P < .001, when comparing patient sera with control sera. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

C3 and C9 binding and CD40L and CD62P expression on normal platelets exposed to serum. Washed normal platelets (from citrated tubes) were incubated with an equal volume (25 μL) serum from patients 1 (♦), 2 (▴), 3 (●), 4 (◇), parents, or controls (○). The patients' serum exhibited increased C3 and C9 binding to normal platelets compared with control sera. Likewise, patient sera resulted in increased CD40L and CD62P expression, suggesting activation. This was not seen when platelets were exposed to normal sera. Serum from the parent bearing the same mutation as the affected patient with aHUS exhibited similar results to the patients, whereas sera from the parents that did not bear the mutation resembled normal sera with the exception of the father of patient 1 (treated at the time of sampling for lymphosarcoma). Results for patients were carried out 3 times, and for the parents and controls twice with reproducible results. *P < .001, when comparing patient sera with control sera. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

Thrombin stimulation in the presence of control sera resulted in maximal platelet activation as demonstrated by 65% anti-CD40L binding (median; range, 34%-78%) and 89% anti-CD62P binding (median; range, 83%-95%). No difference was found using patient sera. The effect of thrombin on complement deposition in the presence of patient or normal sera was tested. C3 deposition on platelets incubated with patient or normal serum increased after thrombin stimulation (median, 63%; range, 47%-72%; or median, 66%; range, 53%-79%, respectively) compared with unstimulated platelets (median, 23%; range, 14%-30%; or median, 5%; range, 2%-10%; patient or normal serum, respectively). Similarly, thrombin stimulation increased C9 deposition (median 70%, range 65%-82% or median 72%, range 63%-80%; patient or normal serum, respectively) as compared to unstimulated platelets (median 17%, range 6%-29% or median 5%, range 1%-15%, patient or normal serum, respectively). Thus thrombin stimulation had a marked effect on complement deposition in the presence of serum, and no differences were found between patients and controls.

Heterologous combination of platelets from one donor with serum from another did not affect C3 and C9 binding in 14 healthy individuals when ABO blood groups were compatible (data not shown). Filtration of serum (when generating PMPs) did not alter C3 and C9 deposition on platelets. Centrifugation of whole blood to PRP and the procedure of washing of platelets and suspension in ABO-matched serum did not lead to platelet activation as assessed by the expression of CD40L or CD62P (data not shown). Platelet counts did not differ before and 2 minutes after addition of patient or normal serum (data not shown).

Serum from patients with aHUS increased PMP numbers and PMPs with bound TF

PMPs generated by incubation of normal washed platelets with patient serum were significantly higher compared with washed platelets incubated with serum from healthy controls (Table 2). Similarly, PMPs with surface-bound TF were significantly elevated when patient sera were used compared with control sera (Table 2). Thrombin stimulation of washed platelets increased the total number of PMPs generated after incubation with patient or normal serum (median, 2380 × 103/mL serum; range, 1633-3548; or median, 2500; range, 1697-3288, respectively) as well as TF-positive PMPs (median, 2220; range, 1612-3367; or median, 2310; range, 1584-3117, respectively), and no significant differences were found between sera from patients and controls.

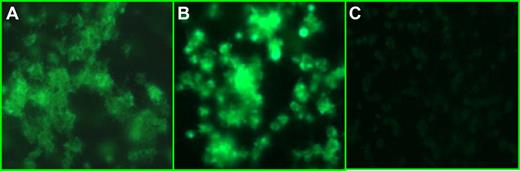

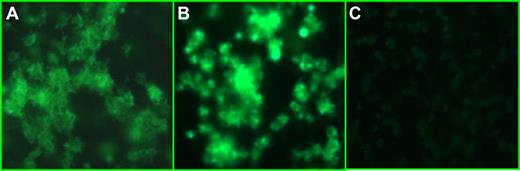

Plasma from patients with aHUS leads to CD62 expression and platelet aggregation

Platelet activation was further investigated by CD62P expression and aggregate formation. Incubation of patient-derived citrate plasma with normal washed platelets induced CD62 expression and platelet aggregation as demonstrated by immunofluorescence in Figure 5A,B. This effect was specific for the patient plasma and was not observed for plasma derived from healthy controls (n = 4; Figure 5C).

Plasma from patients induced platelet aggregation. Combination of patient plasma (panel A, patient 2; panel B, patient 3) with normal platelets induced CD62 expression on the platelet surface and aggregation not seen when normal heterologous plasma was added to the same platelets (C). The figure shows one representative experiment. Similar results were obtained using plasma from patients 1 and 4.

Plasma from patients induced platelet aggregation. Combination of patient plasma (panel A, patient 2; panel B, patient 3) with normal platelets induced CD62 expression on the platelet surface and aggregation not seen when normal heterologous plasma was added to the same platelets (C). The figure shows one representative experiment. Similar results were obtained using plasma from patients 1 and 4.

FH regulates complement deposition and platelet activation

Preincubation of normal platelets with normal FH before addition of patient serum reduced C3 and C9 binding (Figure 6A,B) as well as expression of CD40L and CD62P (Figure 6C,D) on the platelets significantly. When serum from healthy donors was added to normal platelets, minimal C3 and C9 levels as well as CD40L and CD62P expression was observed on the platelet surface. Addition of normal FH to platelets before exposure to normal sera did not alter this effect (Figure 6A-D). When washed platelets were stimulated with thrombin, C3 or C9 deposition was not altered by preincubation of platelets with normal FH before addition of thrombin and serum from patients or controls (data not shown).

Normal FH reduces C3 and C9 binding and CD40L and CD62P expression after exposure to patient serum. Incubation of patient sera with normal washed platelets (patients 1 [♦], 2 [▴], 3 [●], and 4 [◇], from citrated tubes; other platelet donors than in Figure 4) led to C3 and C9 deposition as well as CD40L and CD62P expression. Preincubation of washed platelets with normal FH before addition of patient serum reduced C3 and C9 binding (A,B) as well as expression of CD40L and CD62P (C,D) on normal platelets. Normal serum added to normal platelets (○) led to minimal C3 and C9 binding or CD40L and CD62P expression on the platelet surface; this pattern was not altered in the presence of normal FH. Results were carried out 3 times with reproducible results. *P < .001, when comparing platelets incubated with patient serum with and without normal FH and when comparing patient sera with control sera. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

Normal FH reduces C3 and C9 binding and CD40L and CD62P expression after exposure to patient serum. Incubation of patient sera with normal washed platelets (patients 1 [♦], 2 [▴], 3 [●], and 4 [◇], from citrated tubes; other platelet donors than in Figure 4) led to C3 and C9 deposition as well as CD40L and CD62P expression. Preincubation of washed platelets with normal FH before addition of patient serum reduced C3 and C9 binding (A,B) as well as expression of CD40L and CD62P (C,D) on normal platelets. Normal serum added to normal platelets (○) led to minimal C3 and C9 binding or CD40L and CD62P expression on the platelet surface; this pattern was not altered in the presence of normal FH. Results were carried out 3 times with reproducible results. *P < .001, when comparing platelets incubated with patient serum with and without normal FH and when comparing patient sera with control sera. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.

FH reduces PMPs with bound TF

Preincubation of normal platelets with FH before addition of patient serum significantly reduced PMPs in number as well as PMPs with surface-bound TF (Table 2). There was no difference in PMP numbers or TF-positive PMPs in serum from healthy controls with or without preincubation with FH (Table 2). When washed platelets were stimulated with thrombin, PMP numbers and TF-positive PMPs were not altered by preincubation of platelets with normal FH before addition of thrombin and serum from patients or controls (data not shown).

FH-E1198stop mutant enables C3 deposition on the surface of normal platelets

FH- and C3-deficient plasma to which C3 was added before incubation with normal platelets exhibited 45% and 57% C3 binding in 2 experiments. When the platelets were preincubated with normal FH, C3 binding was reduced considerably, to 13% and 25%, respectively. Incubation with FH-E1198Stop mutant instead of normal FH did not have the same protective effect and exhibited more C3 deposition (39% and 53%). The combination of normal FH and FH-E1198Stop mutant exhibited a partial reduction in C3 binding (28% and 40%), indicating that the presence of FH-E1198Stop mutant did not totally abrogate the effect of normal FH. When no C3 or factor H were added to the FH-deficient serum, binding of the anti-C3 antibody was 5% and 8% in the 2 respective experiments (data not shown).

Discussion

HUS-associated mutant FH variants have previously been shown to have reduced binding capacity to endothelial cells28 and platelets,12 as well as reduced complement regulatory activity on the endothelial cell surface.29 The current study shows that the same phenomenon applies to platelets in which dysregulation of complement on the platelet surface leads to platelet activation and aggregation. The FH-E1198Stop mutant exhibited defective binding to platelets and enabled complement deposition on the surface of normal platelets. Serum from all 4 patients with aHUS exhibited dysfunctional FH, leading to complement deposition on the surface of normal platelets, an effect that was abrogated by preincubating platelets with normal FH before addition of patient serum. The results indicate that FH mutations result in complement activation on the surface of platelets and platelet activation.

The patients described in this study exhibit the same dysfunction with regard to complement activation on platelets in spite of having 4 different mutations. In patients 1, 2, and 4, the product of the mutated allele is expressed as demonstrated by normal FH levels, in patient 2 by cDNA studies,5 and in patient 4 by immunoblotting, showing one normal and one truncated band (data not shown). Patients 2 and 4 have mutations affecting the same amino acid, which in patient 4 leads to a premature stop codon. In these patients, the mutated FH is dysfunctional. For patient 3, the essential Cys residue at position 870 in SCR 15 is replaced by Arg. Exchanges of framework Cys residues may cause a block in protein secretion.50,51 Based on the reduced FH plasma levels in this patient, it is suggested that the product of the mutant FH allele is retained in the cytoplasm and is not secreted. Consequently, the intact allele is expressed and the protein secreted, which results in an overall reduction of FH plasma levels. Thus, the various mutations observed here, which either reflect amino acid ex-changes in the C-terminal SCR 20 or reduced FH plasma levels, result in FH dysfunction and defective complement regulation on the platelet surface.

Patients with aHUS are usually heterozygous for FH mutations.43 One of the parents of patients 1, 3, and 4 bears the same mutation as their respective child and exhibited the same degree of FH dysfunction on platelets. This leads to the intriguing question as to why these parents do not develop HUS. Previous studies have shown that, in addition to mutations in FH, certain constellations of predisposing polymorphisms increase the risk of developing HUS.43 Apparently, the combination of polymorphisms and/or specific mutations may cause dysfunction not seen in the patients' parents,43,52,53 but other environmental or infectious agents may contribute to the disease process. We suggest that FH dysfunction contributes to complement activation on patient platelets, but an additional insult may be required to trigger fulminant activation and thrombocytopenia as seen in manifest aHUS.

As most patients are heterozygous, the patients and the parents (of patients 1, 3, and 4) bearing the same mutation all have one intact normal allele. In patients 1 and 3, risk-associated polymorphisms42,43 were demonstrated on the other allele (E936D in patient 1, homozygous 936D in patient 3), which may contribute to the dysfunction. There is also the possibility that the product of the mutated allele inactivates the product of the normal allele in a dominant-negative manner. For this reason we combined the FH-E1198Stop mutant with normal FH, but the combination did not totally neutralize the beneficial protective effect of normal FH on the surface of platelets. It has been suggested that FH forms oligomers54 mediated at the C terminus. Heinen et al29 showed that wild-type and mutant FH form dimers, and that wild-type protein possibly forms dimers more readily. Thus, when combining mutated and normal FH, these proteins may not preferentially form dimers with each other, but normal protein may form a dimer with normal protein. Recent results show, however, that circulatory FH is mostly monomeric.55 Reduced regulatory activity in the heterozygous patient is thus most probably related to reduced binding and/or function of the mutated allele in the face of an imminent insult. In addition, risk-associated polymorphisms encoded by the other allele may contribute to complement dysregulation.

The sheep hemolysis test has been used by us and by others5,41,56,57 as a method for detection of FH dysfunction on the cell surface. The method is simple and entails combining serum with sheep erythrocytes and measurement of complement-mediated hemolysis. When hemolysis is detected, dysfunction of FH is defined by reduced hemolysis after addition of normal FH to the serum. The results vary depending on the batch of erythrocytes used and from one laboratory to another. Zipfel and coworkers have therefore chosen to carry out the hemolysis assay in FH-depleted serum (to which purified FH, mutant or normal, is added) in order to achieve more reliable results.29 FH depletion is a time-consuming procedure, which also requires immediate assay, as C3 is consumed in FH-depleted serum. In the current study, the hemolysis assay was carried out using serum from the patients or their parents. In all patients the assay showed FH dysfunction, which could be normalized after addition of normal FH. However, 2 of the parents bearing the same mutation (the father of patient 3 and the mother of patient 4) exhibited a normal hemolysis assay. This is surprising, as the FH-E1198Stop mutant purified in this study was found to be dysfunctional and was isolated from the serum of the mother of patient 4. This result therefore suggests that the hemolysis assay may not be absolutely reliable for detection of FH dysfunction, and that other factors affect the lytic activity of the serum. The assay present herein, in which C3 from patient sera deposited on normal platelets as detected by flow cytometry, seems to give more reliable results.

The presence of C3 on platelets has been documented in clinical conditions in which thrombocytopenia or thrombosis occur, such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), in which complement deposition secondary to immunoglobulin binding has been suggested to promote thrombocytopenia,35 and on platelets from patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, in which activation of the alternative complement pathway occurs due to the PIG-A mutation and lack of membrane-bound complement regulators.58,59 The interaction between platelets and complement appears to work both ways (ie, in addition to complement-mediated platelet activation,60-62 complement may be activated on the membrane of activated platelets).46,63-65 The platelets used in this study were not preactivated, as determined by the lack of CD40L on their surface; thus, we conclude that complement deposition led to platelet activation and not vice versa. Previous studies have shown that, in the presence of C3, platelet aggregation was induced via the arachidonic acid pathway,66-68 and thrombin-induced platelet aggregation was increased.63 The present study shows that, in the presence of mutated FH, complement products are deposited on surface of platelets, resulting in a prothrombotic state as exhibited by the release of TF-expressing PMPs. We suggest that normal FH regulates C3 binding to the platelet surface and prevents complement-mediated platelet activation from occurring, a function that is compromised in aHUS due to FH mutations.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

This study was presented in part in poster form at the XXI International Complement Workshop, Beijing, China, October 22-27, 2006.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Eva Holmström for assistance with assays of factor H function using the sheep hemolysis test.

This study was supported by grants from The Swedish Research Council (K2007-64X-14008-07-3), Crafoord Foundation, The Fund for Renal Research, Swedish Renal Foundation, Magnus Bergvalls Stiftelse, Tobias Foundation, Crown Princess Lovisa's Society for Child Care, The Maggie Stephen's Foundation, The Foundation for Fighting Blood Disease, Thelma Zoegas Foundation, Sven Jerring Foundation, Konung Gustaf V's 80-årsfond, and the Blood and Defense Network at Lund University (all to D.K.); and The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Kidneeds (to P.F.Z.). D.K. is the recipient of a clinical-experimental research fellowship from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Authorship

Contribution: A.-l.S. designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; F.V.-S. designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and assisted in writing the paper; S.H. performed the purification of the factor H mutant; A.-C.K. performed the research and analyzed data; K.-H.G., R.R., A.G., and O.B. collected data and assisted in writing the paper; P.F.Z. performed research, analyzed data, and assisted in writing the paper; D.K. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Diana Karpman, Department of Pediatrics, Lund University, 22185 Lund, Sweden; e-mail: diana.karpman@med.lu.se.

![Figure 6. Normal FH reduces C3 and C9 binding and CD40L and CD62P expression after exposure to patient serum. Incubation of patient sera with normal washed platelets (patients 1 [♦], 2 [▴], 3 [●], and 4 [◇], from citrated tubes; other platelet donors than in Figure 4) led to C3 and C9 deposition as well as CD40L and CD62P expression. Preincubation of washed platelets with normal FH before addition of patient serum reduced C3 and C9 binding (A,B) as well as expression of CD40L and CD62P (C,D) on normal platelets. Normal serum added to normal platelets (○) led to minimal C3 and C9 binding or CD40L and CD62P expression on the platelet surface; this pattern was not altered in the presence of normal FH. Results were carried out 3 times with reproducible results. *P < .001, when comparing platelets incubated with patient serum with and without normal FH and when comparing patient sera with control sera. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/11/10.1182_blood-2007-08-106153/6/m_zh80080818240006.jpeg?Expires=1769285366&Signature=oIZrIsxCAaHdY3McCIX5l90cI89p-gvQsb4HJQ8UnXIOXQd-8MfRl284F71FKs-zP~x6DXOEg01nB-dHawj5onxJJcCLF3dXhWnNkNvU2baBtoflqX8EHBO2VfF47kIz~nKynaDxkgPutXPfLQwi9b-DRfJkzNBFu8uyqEYqJ7HCQVZrqF~tk27N4VI7~mjVy7qIgEs2NmdOnixKlr4KBG6lFSi8ALwTSCrq74DHVo1JSOIte~ww5OyJObs7KsGS81bwgECAFTl~x40k1jkiKAV292Gfli8wvv1AW7ofEDzJJ5tQB4myL9HtZuXxkyaIm0whVZlkz7~KyHNg3sIQlw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Normal FH reduces C3 and C9 binding and CD40L and CD62P expression after exposure to patient serum. Incubation of patient sera with normal washed platelets (patients 1 [♦], 2 [▴], 3 [●], and 4 [◇], from citrated tubes; other platelet donors than in Figure 4) led to C3 and C9 deposition as well as CD40L and CD62P expression. Preincubation of washed platelets with normal FH before addition of patient serum reduced C3 and C9 binding (A,B) as well as expression of CD40L and CD62P (C,D) on normal platelets. Normal serum added to normal platelets (○) led to minimal C3 and C9 binding or CD40L and CD62P expression on the platelet surface; this pattern was not altered in the presence of normal FH. Results were carried out 3 times with reproducible results. *P < .001, when comparing platelets incubated with patient serum with and without normal FH and when comparing patient sera with control sera. Results are expressed as median plus or minus SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/11/10.1182_blood-2007-08-106153/6/m_zh80080818240006.jpeg?Expires=1769709944&Signature=b-xGG9btAvrLwURwcvJORVPVWB0efwpIh3debKd96v2EtMbznaf90LwOBtQ7nqX8sh48P32aELzeJvcSeU1kbhpxHpnbm~FQME8Fmb~BwIW2S8JHUe7MsGadSGN7h7WuEqxes671vAQb~XawR8H0Eh7uTDXIvuKD3H0aj1KELKm40FKvZtjq3lu5450PfvQYN4x4iq0QtDj8h-k1KVa0ao0~rVLBaSPfS1ket86rBVXG4w0oLcH1XKNIjRvY5YNk1Tc6k4vfG5b0z~DuyoIKbDl48pJCaH8BvYXg~nkuYy8JwRrpX6BWvSE0QyVfTGHv1ylUxauTURCCoJfvv1VhIw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)