Abstract

Ikaros—a factor that positively or negatively controls gene transcription—is active in murine adult erythroid cells, and involved in fetal to adult globin switching. Mice with Ikaros mutations have defects in erythropoiesis and anemia. In this paper, we have studied the role of Ikaros in human erythroid development for the first time. Using a gene-transfer strategy, we expressed Ikaros 6 (Ik6)—a known dominant-negative protein that interferes with normal Ikaros activity—in cord blood or apheresis CD34+ cells that were induced to differentiate along the erythroid pathway. Lentivirally induced Ik6-forced expression resulted in increased cell death, decreased cell proliferation, and decreased expression of erythroid-specific genes, including GATA1 and fetal and adult globins. In contrast, we observed the maintenance of a residual myeloid population that can be detected in this culture system, with a relative increase of myeloid gene expression, including PU1. In secondary cultures, expression of Ik6 favored reversion of sorted and phenotypically defined erythroid cells into myeloid cells, and prevented reversion of myeloid cells into erythroid cells. We conclude that Ikaros is involved in human adult or fetal erythroid differentiation as well as in the commitment between erythroid and myeloid cells.

Introduction

The transcription factor Ikaros (also known as LyF-1) was first described to interact with Cd3δ and TdT promoters in murine thymocyte cells.1,2 Its sequence is highly conserved between mice and humans,3-5 and its expression is high in the developing and adult hematopoietic systems.1,6 Ikaros proteins are characterized by the presence of 2 Krüppel-like zinc finger domains. The N-terminal domain is involved in DNA binding,2,7 while the C-terminal domain is required for homo- or heterodimerization with family members and is composed of 2 zinc fingers.8 The Ikaros gene contains 7 translated exons and encodes 9 isoforms by means of alternative splicing that alters expression of exons 3 to 6.2,7 In these different proteins, the number of N-terminal zinc fingers varies from 0 to 4; this combination determines DNA binding affinity. At least 3 zinc fingers in this domain are necessary to efficiently bind to DNA. Ik1, Ik2, Ik3, and IKX are considered as functional isoforms. However, Ik4 can only bind DNA on palindromic sequences.7 Ik5, Ik6, Ik7, and Ik8 are considered dominant-negative (DN) isoforms because of their capacity to bind other isoforms and their inefficiency to bind DNA.8

Gene-targeting studies evidenced the fundamental role of Ikaros in hematopoiesis, in particular in T and B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) and dendritic cells, and stem cells.9-12 In addition, analysis of Ikaros L/L mice (insertion of the β-Gal gene in exon-2 of the Ikaros gene) revealed that Ikaros is expressed at low levels in a majority of Ter-119+ erythroid cells.10 Other studies of Ikaros DN (deletion of exon 7) and null (deletion of dimerization domain) mice show that Ikaros is important for erythroid differentiation.13 These mice display a decrease of erythroid precursor numbers, and a drop in hematocrit levels 2 to 3 weeks after birth. In MEL (murine erythroleukemia) cells, Ikaros is associated with the chromatin remodelling PYR complex which binds to an intergenic domain between the γ-globin and β-globin genes, and facilitates the switch between these 2 globins.14 Moreover, Ikaros null mice show a delay in murine embryonic to adult β-globin switching, due to the lack of the chromatin remodeling PYR complex. Delayed switching between human γ- and β-globins is also observed in mice with a human β-globin minilocus and lacking the Ikaros gene.15 These studies show that Ikaros is necessary to the formation of the PYR complex, and to switching of murine and human globins.16,17 The role of Ikaros in erythropoiesis is confirmed by another Ikaros mutation: Ikaros plastic mice have a single amino acid change in the third zinc finger of the N-terminal domain (ENU-induced nucleotide mutation), and die between embryonic day (E) 15.5 and E17.5 with severe anemia18 ; numbers of erythroid progenitors (erythroid colony-forming units [CFUs-E] and erythroid blast-forming units [BFUs-E]), normoblasts, and nonnucleated reticulocytes are reduced, which is due to a failure of normal erythroblast growth and differentiation.

The earliest committed erythroid progenitor is the BFU-E, which then differentiates into CFUs-E. The more immature morphologically identifiable cells are proerythroblasts. Hemoglobinization begins at the basophilic stage, and increases in polychromatophilic erythroblasts.19 Orthochromatophilic erythroblasts undergo terminal maturation, including extrusion of the nucleus to produce enucleated mature erythrocytes. The human β-globin locus contains different genes that are successively expressed during ontogeny.16,20,21 γ-globin genes are first expressed in fetal liver and cord blood (CB) erythropoiesis.19,22 Shortly after birth, a switch between fetal and adult globins allows the expression of δ- and β-globin genes, and the decrease of γ-globin gene expression.21,23,24 Adult erythropoiesis recapitulates fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching in the so-called “compressed switch.”25-27 Fetal-to-adult switch needs interaction of transcription factors and chromatin remodeling proteins with the locus control region (LCR).16,17,21,28 Analyses of transcription factors revealed the importance of erythropoiesis regulation at the transcriptional level. GATA1 is crucial for differentiation, expression of erythroid genes (such as β-globin, FOG1, EKLF, and NFE2), and for survival of erythroid cells.29 GATA1 functions are in part controlled by interaction with FOG1, which is itself involved in terminal erythroid maturation.30 EKLF allows expression of β-globin and the erythropoietin receptor, and is essential for switching process between γ- and β-globin in adult erythroid cells.31,32 NFE2 is also involved in α- and β-globin expression.33 In contrast, the Ets factor PU1, which promotes differentiation of lymphoid and myeloid lineages, inhibits erythroid differentiation through its antagonism with GATA1, whereas it is necessary for proliferation of early erythroid progenitors.34

In this work, we studied the role of Ikaros in human erythropoiesis from CB, and its role in globin switch in adult cells. Using a similar strategy as in a previous study,35 we inhibited Ikaros function by overexpression of the DN Ik6 isoform throughout in vitro erythroid differentiation from CB or apheresis CD34+ progenitor cells.

Methods

Approval of these studies was obtained from the Institute Paoli-Calmettes institutional review board (Comité d'Orientation Strategique). Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Primary cells and cell lines

CB or apheresis (adult mobilized peripheral blood [mPB]) samples were obtained after informed consent from pregnant mothers or patients with cancer, respectively. CD34+ cells were enriched from CB or mPB mononuclear cells using immunoselection with the magnetic-activated cell sorter (MACS) technology according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany).

The MS5 murine stroma cell line was maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Cambrex, Viviers, Belgium) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Lentiviral vectors

The Ik6 cDNA was obtained by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers as previously described.35 The Flag sequence was inserted in 5′ of Ik6 cDNA, upstream of the initiation codon. In a first step, mutation of ATG for ATC, inserting a ClaI site, was introduced by PCR with primers Ik ClaI start and Ik XhoI stop (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The resulting PCR product was subsequently cloned into the pCRII vector and sequenced. Flag Bam/Cla oligos were annealed, introduced in opened BamHI/ClaI Ik6 pCRII vector, cloned, and sequenced. In a second step, the Flag-Ik6 sequence was cloned into TRIP ΔU3 EF1α enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP; a gift from P. Charneau, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), called EF1 GFP in place of EGFP, using the BamHI and XhoI sites.36 This vector was called EF1 IK6 (Figure S1). Production of lentiviral vectors and assays for the detection of replication competent lentiviruses were previously described.37

Erythropoietic cell cultures and lentiviral transductions

CD34+ cells from CB or mPB were cultured as previously described.22 Briefly, cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 20% BIT, 900 ng/mL ferrous sufate, and 90 ng/mL ferric nitrate (basal medium). In the first step (days 0-10), 104/mL CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of 10−6 M hydrocortisone, 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), 5 ng/mL IL-3, and 3 IU/mL erythropoietin. On day 3, these cells were transduced with 2500 ng of p24 antigen of lentivirus per 106 cells/mL of culture medium in the presence of protamine sulfate (8 μg/mL). After 24 hours, the lentiviral medium was removed, and cells were replated in culture medium at 200 000 cells per 4 mL. In the second step (days 10-13), cells were diluted at 5 × 104 or 105 cells/mL (for CB or mPB, respectively) and cocultured on an adherent MS5 stromal layer in basal medium supplemented with erythropoietin. In the third step (days 13-20), cells were cultured on MS5 cells in basal medium without cytokine.

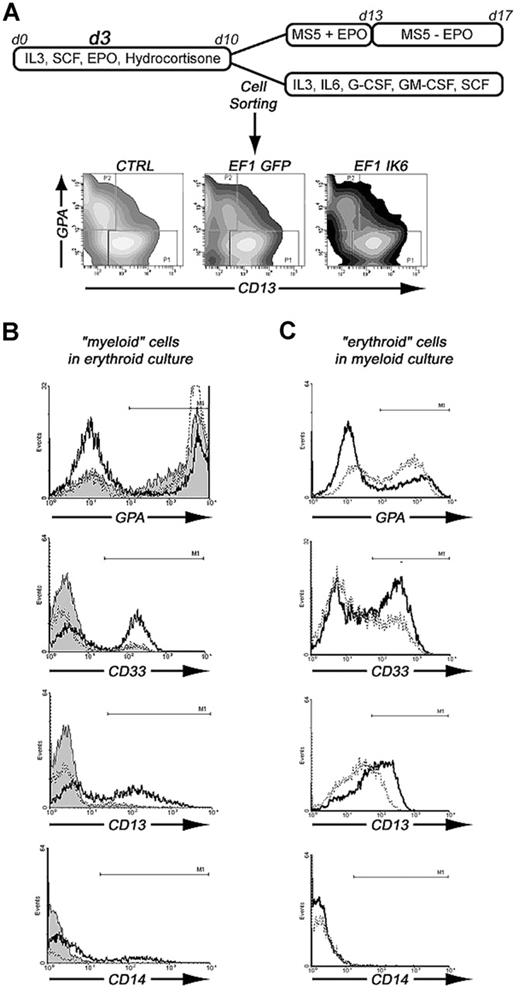

In an alternative experiment, on day 10, cells were sorted on a FACSAria flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson/BD, San Jose, CA) in 2 populations either CD13+/GPA− cells or CD13−/GPA+ cells. One-half of the sorted cells were replated in erythroid conditions as previously described. At 7 days later, cells were analyzed using flow cytometry and quantitative PCR. The second half of sorted cells were plated in “myeloid” medium containing IMDM, 20% BIT, IL-3 (10 ng/mL), IL-6 (10 ng/mL), G-CSF (10 ng/mL), GM-CSF (10 ng/mL), and SCF (100 ng/mL). At 7 days later, cells were analyzed using flow cytometry and quantitative PCR.

Flow cytometric analyses

The following mAbs and their isotypic controls were purchased from Beckman-Coulter (Marseille, France): FITC- and PE-conjugated CD36, PE- and PC5-GPA (glycophorin-A), PE- and PC7-CD13 (N-aminopeptidase), PE-CD33, PE-CD111 (nectin 1), PE-CD117 (c-Kit), PE- and PC5-CD45, PC5-CD71 (transferrin receptor), and PC5-CD34.

After staining, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson/BD Immunocytometry Systems [BDIS], San Jose, CA) equipped with the DIVA analysis software (BDIS).

Cell death was measured using an annexin V–Cy5 assay.

Cytospin and immunofluorescence

The cells were cytospun on glass slides (approximately 100 000 cells per slide) at 72g for 5 minutes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 20% FCS. Analyses of cell morphology and transduction efficiency were performed with either May-Grünwald-Giemsa or immunofluorescence staining, respectively. We stained cells with a mouse anti-Flag antibody (2 μg/mL; Sigma, St Louis, MO), and an Alexa-Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse antibody (2 μg/mL; Invitrogen) as secondary antibody.

RNA and DNA isolation, RT-PCR, and quantitative PCR

Total RNA and DNA were extracted from cells with a Nucleospin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France). cDNA synthesis was performed as previously described.38 To reveal all Ikaros isoforms, classical PCR was done with primers matching sequences on exons 2 and 7 (Table S1 “Ikaros isoforms”); PCR products were loaded on agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Quantitative PCR was performed to evaluate the total amount of endogenous Ikaros mRNA using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and an ABI7700 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), or using Faststar DNA master SYBR Green and a Light Cycler apparatus (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The primers (Table S1 “Ikaros total”) that match in exon 7 were used. Flag Ikaros transgene expression was quantified with Flag Ikaros primers (Table S1 “Flag Ikaros”). The plasmid standards for β-globin, γ-globin, α-globin, EKLF, NFE2, FOG1, and EPOR were obtained by cloning specific amplicons of each gene with respective primers (Table S1) in pCRII vector using the TA-Cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequencing. The plasmid standard for the other genes was an image clone (Invitrogen). Gene expression was normalized using the endogenous GAPDH gene expression as an internal standard.

The expression of 184 apoptotic, transcription factor, and cell-cycle genes was tested from 2 μg cDNA using SYBR Green reagent on an ABI7700 system (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression was normalized, using 4 relative endogenous gene expressions (GAPDH, HPRT, ubiquitin, and β-actin).39

Immunoprecipitation

The supernatant of 106-cell NP40 lysis was incubated with anti-Tag protein G–Sepharose for 3 hours at 4°C. Specific anti-Tag proteins were loaded on an acrylamide gel. Western blot was revealed with an anti Ikaros antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Results

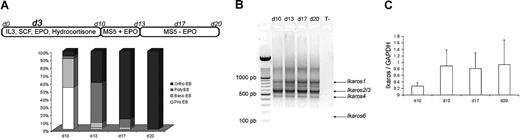

Expression of endogenous Ikaros during erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells from human CB and from human mPB

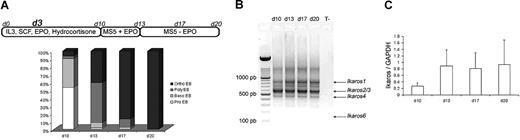

Purified CD34+ cells from human CB and adult mPB were cultured in erythroid conditions, as previously described.22 The 3 culture steps produced similar results in our hands: at the end of the first step (day 10), the cell population was composed of 53% proerythroblasts (pro-EBs) and 36% basophilic erythroblasts (baso-EBs). At the end of the second step (day 13), cultured cells were composed of 50% polychromatophilic erythroblasts (poly-EBs) and 40% orthochromatophilic erythroblasts (ortho-EBs). During the third step (13-20 days), cultured cells were composed of 10% poly-EBs and 84% ortho-EBs, and 100% ortho-EBs were detected at day 17 (intermediate day) and at day 20, respectively (Figure 1A). On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, total RNA was extracted from normal cultured cells and reverse transcribed into cDNA. Figure 1B shows expression of different active endogenous Ikaros isoforms (Ikaros 1 [IK1], Ikaros 2/3 [IK2/3], and Ikaros 4 [IK4])—as well as the absence of endogenous Ik6—at all stages of CB CD34+ cell cultures. The pattern was identical for adult erythroid cultured cells (data not shown). An estimation of the total quantity of the mRNAs that encode the different Ikaros isoforms (relative to GAPDH) by quantitative PCR did not show significant variations between days 10 and 20 of the cultures (Figure 1C).

Ikaros expression during cytokine induced erythroid differentiation. (A) Highly purified CD34+ cells from human CB or from human adult mPB samples were maintained in conditions that drive differentiation to the erythoid lineage. On day 3, cells were transduced with EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6 vectors. Cultures were stopped on day 20 for CB samples, and on day 17 for mPB samples. On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, erythroblast subsets derived from CD34+ CB cells were identified by May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Results are expressed as the mean percentage in 7 independent experiments. (B) On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, total RNA was extracted from cultured erythroid cells in CB samples, and expression of endogenous Ikaros isoforms was visualized by ethidium bromide staining of 2% agarose gel after RT and 40 cycles of amplification of cDNA with primers designed to match exons 2 and 7 (Ikaros isoforms in Table S1) in order to amplify all Ikaros isoforms. Arrows indicate the positions of Ik1-, Ik2/3-, and Ik4-expressed isoforms. (C) On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, total RNA was also extracted from adult cultured erythroid cells. Expression of Ikaros in CB was quantified using quantitative PCR and normalized relatively to endogenous GAPDH gene expression. Results are shown with means (± SEM) for 4 to 7 independent CB samples.

Ikaros expression during cytokine induced erythroid differentiation. (A) Highly purified CD34+ cells from human CB or from human adult mPB samples were maintained in conditions that drive differentiation to the erythoid lineage. On day 3, cells were transduced with EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6 vectors. Cultures were stopped on day 20 for CB samples, and on day 17 for mPB samples. On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, erythroblast subsets derived from CD34+ CB cells were identified by May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Results are expressed as the mean percentage in 7 independent experiments. (B) On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, total RNA was extracted from cultured erythroid cells in CB samples, and expression of endogenous Ikaros isoforms was visualized by ethidium bromide staining of 2% agarose gel after RT and 40 cycles of amplification of cDNA with primers designed to match exons 2 and 7 (Ikaros isoforms in Table S1) in order to amplify all Ikaros isoforms. Arrows indicate the positions of Ik1-, Ik2/3-, and Ik4-expressed isoforms. (C) On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, total RNA was also extracted from adult cultured erythroid cells. Expression of Ikaros in CB was quantified using quantitative PCR and normalized relatively to endogenous GAPDH gene expression. Results are shown with means (± SEM) for 4 to 7 independent CB samples.

Expression of transgenic DN Ik6 isoform during induced erythroid differentiation of transduced cells

As previously mentioned, we did not detect endogenous Ik6 mRNA in CB or mPB differentiating cells (Figure 1B). On day 3 of cultures, fetal and adult cells were transduced with the EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6 vectors. The percentage of transduction was analyzed using immunofluorescence: 30% of CB cultured cells expressed Ik6 on day 10. The relative expression of transgenic Ik6 compared with GAPDH was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription (RT)–PCR on days 10, 13, 17, and 20: although it decreased during CB cell differentiation, transgene expression remained 16- to 59-fold higher than endogenous Ikaros expression (Figure S2). Similar results were obtained with transduced adult mPB cells (data not shown).

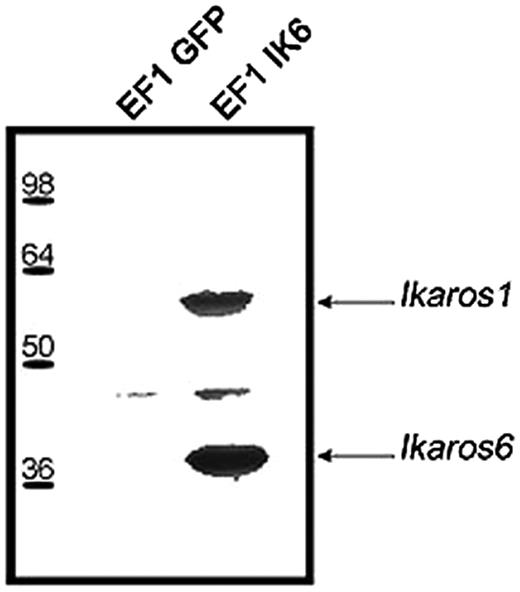

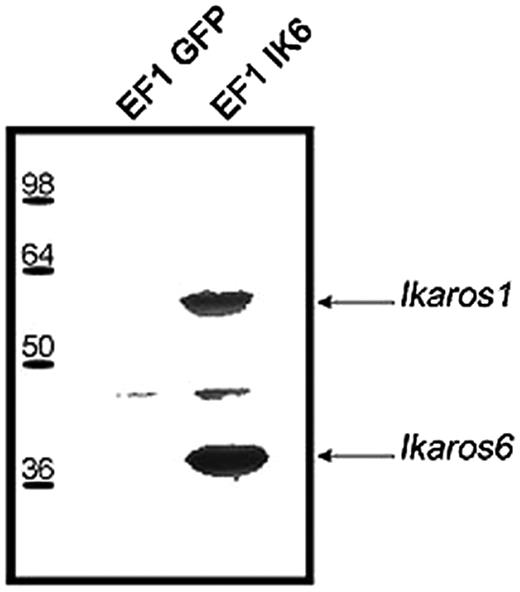

To confirm interactions between endogenous Ikaros and Ik6, EF1 IK6–transduced CB cells or control cells were lyzed on day 7. After immunoprecipitation with an anti-Flag antibody, Western blots revealed with anti-Ikaros showed 2 bands that correspond to Ik1 and Ik6 (Figure 2). These results show that transgenic Ik6 was complexed with endogenous Ikaros.

Expression of transgenic Ik6 in transduced CB cells. Protein extracts of transduced EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6 CB cells were immunoprecipitated at day 7 with an anti-Flag epitope antibody, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Ikaros antibody. Arrows indicate the position of Ik1 and Ik6 immunodetected proteins.

Expression of transgenic Ik6 in transduced CB cells. Protein extracts of transduced EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6 CB cells were immunoprecipitated at day 7 with an anti-Flag epitope antibody, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Ikaros antibody. Arrows indicate the position of Ik1 and Ik6 immunodetected proteins.

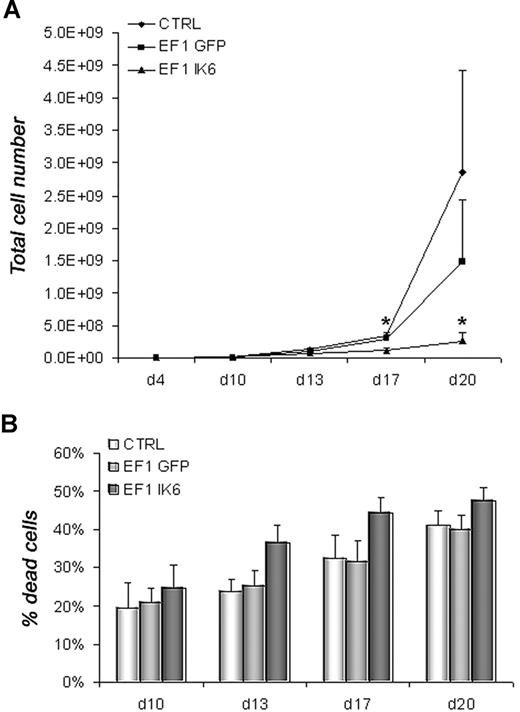

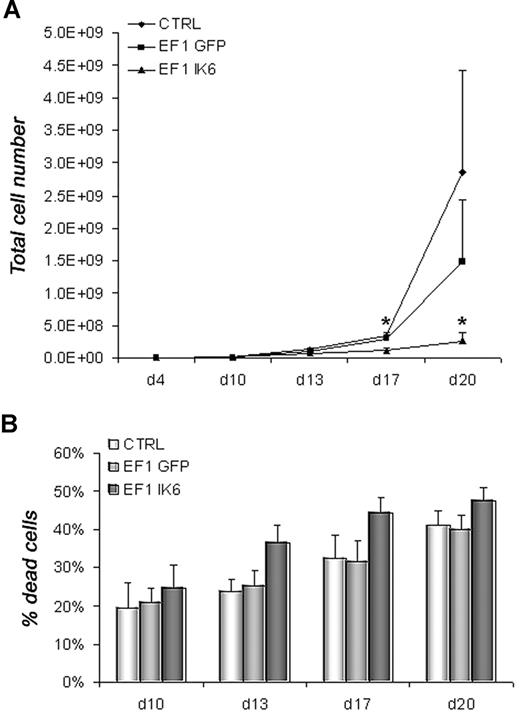

Decrease in cell number and increase in death induced by Ik6 expression

To determine the effects of Ik6 expression, untransduced (CTRL) and transduced (EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6) cells were harvested and counted by trypan blue exclusion on days 10, 13, 17, and 20. In CB cell differentiation, numbers were equivalent between CTRL, EF1 GFP, and EF1 IK6 cells on days 10 and 13. However, following erythropoietin-starvation (days 17 and 20), CTRL and EF1 GFP cell numbers increased, while EF1 IK6 cells did not. Ik6 cell numbers were significantly lower than for CTRL and EF1 GFP (Figure 3A). In parallel, the percentage of dead cells measured with an annexin V assay started to increase at day 13 when CB cells were transduced with EF1 IK6; a modest increase in CTRL and EF1 GFP dead cells was observed on day 20, but remained lower than for EF1 IK6 (Figure 3B). In conclusion, the significant decrease of cell numbers in Ik6-transduced cells probably results both of an increased cell death rate, and a reduced proliferation.

Growth and death of erythroid cells. On day 4, equal numbers of untransduced (CTRL) and transduced (EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6) erythroid cells were replated in erythroid conditions. (A) On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, living untransduced and transduced erythroid cells derived from CB CD34+ cells were counted with trypan blue dye exclusion. The mean cumulative cell numbers of 7 experiments (± SEM) are shown. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions. (B) In erythroid culture of CB CD34+ cells, percentage of dead cells was determined on days 10, 13, 17, and 20 using an annexin V assay (mean values ± SEM for 7 independent experiments).

Growth and death of erythroid cells. On day 4, equal numbers of untransduced (CTRL) and transduced (EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6) erythroid cells were replated in erythroid conditions. (A) On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, living untransduced and transduced erythroid cells derived from CB CD34+ cells were counted with trypan blue dye exclusion. The mean cumulative cell numbers of 7 experiments (± SEM) are shown. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions. (B) In erythroid culture of CB CD34+ cells, percentage of dead cells was determined on days 10, 13, 17, and 20 using an annexin V assay (mean values ± SEM for 7 independent experiments).

Ik6 overexpression disturbs erythroid differentiation without impairing the myeloid potential

To further determine whether Ik6 expression modified erythroid differentiation, cell-surface markers, including CD36, CD71, GPA, and CD111 (“erythroid” markers); CD117 (c-kit) and CD34 (“progenitor” markers); CD45 (human hematopoietic marker lost during erythroid differentiation); and CD33 and CD13 (“myeloid” markers) were analyzed (Figure 4; Table S2). No difference between control and transduced cells was observed until day 17 of culture. At days 17 and 20, the percentages of erythroid marker–positive cells remained equivalent between CTRL, EF1 GFP, and EF1 IK6 cells (Figure 4A). However, corresponding EF1 IK6 cell numbers decreased significantly, except for CD111 (Figure 4B). Percentages of CD117, CD45, and myeloid marker expression increased significantly in EF1 IK6–transduced cells (Figure 4C), although corresponding cell numbers remained unchanged between CTRL, EF1 GFP, and EF1 IK6 (Figure 4D). Thus, forced expression of Ik6 in CB cells resulted in a relative enrichment of the myeloid population at the expense of the erythroid population: the CD13+ population increased, as well as most of the cells expressing CD33, CD117, and CD45 (Figure 4E); however, forced expression of Ik6 did not induce the appearance of “biphenotypic” cells coexpressing GPA and CD13.

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on erythroid cell phenotypes. On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, CB untransduced and transduced cells were harvested and were analyzed for different cell-surface markers (erythroid markers: CD36, CD71, GPA and CD111; progenitor markers: CD117 [c-kit], CD34; human hematopoietic marker: CD45; and myeloid markers: CD33 and CD13) by flow cytometry. On day 20, CD36+, CD71+, GPA+, and CD111+ cell percentages (A) and numbers (B) are shown (mean ± SEM for 7 independent experiments). On day 20, percentages (C) and numbers (D) of CD117+, CD34+, CD45+, CD33+, and CD13+ cells are shown (means ± SEM for 4 to 7 independent experiments). The unchanged results on days 10 and 13 are shown in Table S1. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions; n.s. indicates not significant. Representative dot plots (E) show typical expression of CD13 and GPA, CD13 and CD33, CD13 and CD45, and CD13 and CD117 on day 20 for transduced and untransduced cell populations. Percentage in the quadrants is the percentage of cells present in the defined gate.

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on erythroid cell phenotypes. On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, CB untransduced and transduced cells were harvested and were analyzed for different cell-surface markers (erythroid markers: CD36, CD71, GPA and CD111; progenitor markers: CD117 [c-kit], CD34; human hematopoietic marker: CD45; and myeloid markers: CD33 and CD13) by flow cytometry. On day 20, CD36+, CD71+, GPA+, and CD111+ cell percentages (A) and numbers (B) are shown (mean ± SEM for 7 independent experiments). On day 20, percentages (C) and numbers (D) of CD117+, CD34+, CD45+, CD33+, and CD13+ cells are shown (means ± SEM for 4 to 7 independent experiments). The unchanged results on days 10 and 13 are shown in Table S1. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions; n.s. indicates not significant. Representative dot plots (E) show typical expression of CD13 and GPA, CD13 and CD33, CD13 and CD45, and CD13 and CD117 on day 20 for transduced and untransduced cell populations. Percentage in the quadrants is the percentage of cells present in the defined gate.

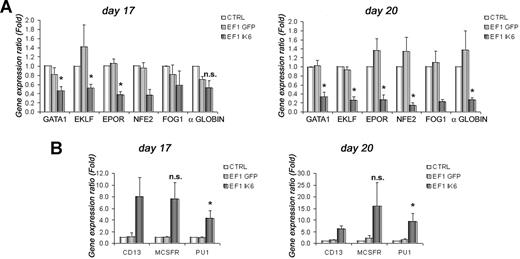

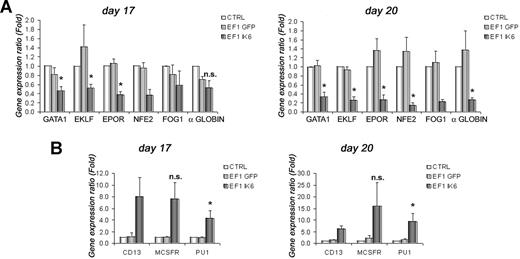

Ik6 overexpression inhibits erythroid gene expression and promotes myeloid gene expression

To test effects of Ik6 on expression of selected erythroid (GATA1, EKLF, EPOR, NFE2, FOG1, and α-globin) and myeloid (CD13, M-CSFR, and PU1) genes, total RNA from cultured cells was extracted at days 10, 13, 17, and 20. RT-PCR was performed, and gene expression was analyzed using quantitative PCR. On days 10 and 13, expression of erythroid genes was unchanged between untransduced and transduced cells (data not shown). However, on day 17, following EPO starvation, expression of GATA1, EKLF and EPOR in EF1 IK6 CB cells decreased significantly when compared with CTRL ( = 1) or EF1 GFP cells (Figure 5A). At this step, expression of NFE2, FOG1, and α-globin was also decreased in EF1 IK6 CB cells. On day 20, the decrease of these 6 erythroid genes was even more drastic, and was significant for GATA1, EKLF, EPOR, NFE2, and α-globin (Figure 5A).

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on gene expression during erythroid differentiation. RT-PCR was performed using total RNA extracted from cultured cells derived from CB CD34+ cells. Gene expression was normalized with GAPDH expression. (A) Relative expression of erythroid genes (GATA1, EKLF, EPOR, NFE2, FOG1, and and α-globin) on days 17 and 20 between untransduced (CTRL) erythroid cells (as reference) and transduced cells. Expression of these genes was reduced in EF1 IK6 erythroid cells. The unchanged results on days 10 and 13 are not shown. (B) Relative expression of myeloid genes (PU1, M-CSFR, and CD13) on days 17 and 20 between untransduced (CTRL) cells (as reference) and transduced cells. Expression of these genes was increased in EF1 IK6 erythroid cells. The unchanged results on day 10 are not shown, and the results on day 13 were similar to that of day 17. Data are mean values (± SEM) for 4 to 7 experiments. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test when comparing with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions; n.s. indicates not significant.

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on gene expression during erythroid differentiation. RT-PCR was performed using total RNA extracted from cultured cells derived from CB CD34+ cells. Gene expression was normalized with GAPDH expression. (A) Relative expression of erythroid genes (GATA1, EKLF, EPOR, NFE2, FOG1, and and α-globin) on days 17 and 20 between untransduced (CTRL) erythroid cells (as reference) and transduced cells. Expression of these genes was reduced in EF1 IK6 erythroid cells. The unchanged results on days 10 and 13 are not shown. (B) Relative expression of myeloid genes (PU1, M-CSFR, and CD13) on days 17 and 20 between untransduced (CTRL) cells (as reference) and transduced cells. Expression of these genes was increased in EF1 IK6 erythroid cells. The unchanged results on day 10 are not shown, and the results on day 13 were similar to that of day 17. Data are mean values (± SEM) for 4 to 7 experiments. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test when comparing with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions; n.s. indicates not significant.

By contrast, at days 13, 17, and 20 of CB cell differentiation, expression of several myeloid genes progressively increased (Figure 5B). Increase in CD13 detection using flow cytometry on EF1 IK6–transduced cells was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR throughout differentiation. In parallel, expression of M-CSFR in EF1 IK6 cells remained drastically higher than for CTRL and EF1 GFP cells. Throughout erythroid differentiation of EF1 IK6 cells, PU1 level of expression was significantly higher than that observed in CTRL and EF1 GFP cells. The increase of myeloid gene expression was detected before the decrease of erythroid gene expression.

This was further confirmed by analysis of 90 apoptotic and 94 various gene (transcription factor, cell-cycle, and apoptotic genes) expressions using multiplex PCR. In Figure S3A, 54 apoptotic genes appeared to be reproducibly modulated in 3 independent experiments on day 17. Among up-regulated genes, there were a majority of “myeloid” genes such as cytokine activator caspase genes (caspase-1, -4, and -5).

Figure S3B shows the modification of 50 genes (a selection of our initial set of 94) on day 20 of CB cell differentiation. Expression of endogenous Ikaros was not modified in EF1 IK6 cells, meaning that transgenic Ik6 did not influence endogenous Ikaros expression. However, Ik6 expression induced an increase of genes that are involved in myelopoiesis (PU1, c-jun), or early and late erythropoiesis (GATA2, Ets-1), and a decrease of important “late” erythroid genes such as GATA1.

Taken together, these results suggest that the expression of genes involved in erythroid differentiation was decreased in the Ik6-transduced population, while that of genes involved in myeloid differentiation was increased.

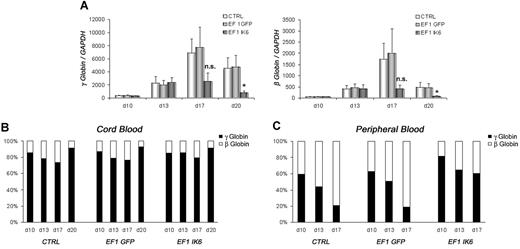

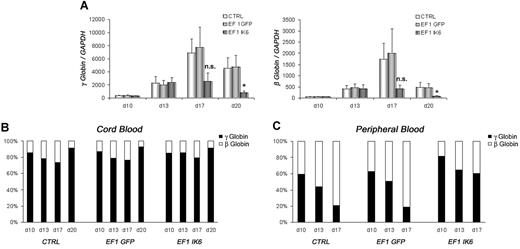

Ik6 overexpression prevents human globin switch

γ- and β-globin expression in CB EF1 IK6 cells was drastically reduced at day 17, and significantly reduced at day 20 (Figure 6A). However, the relative expression of the 2 globins in CTRL, EF1 GFP, and EF1 IK6 cell populations was unchanged throughout CB erythroid differentiation (Figure 6B). Similarly, expression of γ- and β-globin was dramatically reduced in adult EF1 IK6 cells at day 17. During mPB cell erythroid differentiation, the “compressed switch” occurred: the proportion of γ-globin decreased (59% to 21%) in favor of β-globin (41% to 79%) expression in CTRL and EF1 GFP cells. However, when adult cells expressed Ik6, the proportion of γ-globin cells (82% to 60%) remained higher than β-globin cells (18% to 40%) on days 10, 13, and 17 (Figure 6C), thus suggesting that Ik6 expression prevented a “compressed switch” between γ-globin and β-globin in adult cells.

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on γ- and β-globin genes. On the indicated days, RT-PCR was performed using total RNA extracted from cultured erythroid cells derived from CB and mPB CD34+ cells. (A) Expression of γ-globin and β-globin in fetal cDNA erythroid cells on days 10, 13, 17, and 20 is normalized to GAPDH gene expression. Data are mean values (± SEM) for 4 to 7 experiments. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions. (B) Relative expression between γ-globin and β-globin in fetal erythroid cells is shown as the mean of 4 to 7 independent experiments. (C) Relative expression between γ-globin and β-globin is shown in adult erythroid cells in which “compressed switch” normally occurs, and was delayed in Ik6-transduced cells.

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on γ- and β-globin genes. On the indicated days, RT-PCR was performed using total RNA extracted from cultured erythroid cells derived from CB and mPB CD34+ cells. (A) Expression of γ-globin and β-globin in fetal cDNA erythroid cells on days 10, 13, 17, and 20 is normalized to GAPDH gene expression. Data are mean values (± SEM) for 4 to 7 experiments. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions. (B) Relative expression between γ-globin and β-globin in fetal erythroid cells is shown as the mean of 4 to 7 independent experiments. (C) Relative expression between γ-globin and β-globin is shown in adult erythroid cells in which “compressed switch” normally occurs, and was delayed in Ik6-transduced cells.

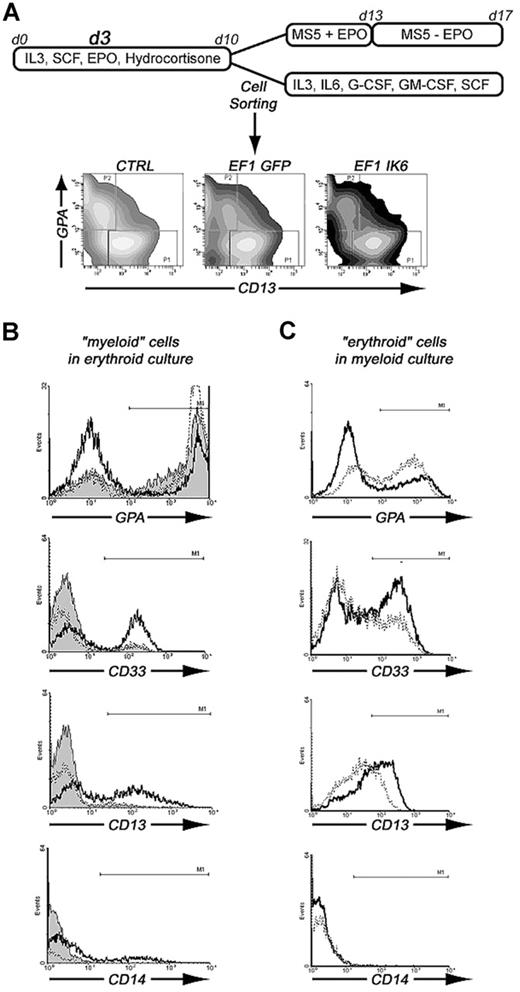

Ik6 overexpression inhibits erythropoiesis and favors myelopoiesis

To test whether Ikaros is involved in erythoid or myeloid commitment, we sorted 2 cell populations after transduction with EF1 GFP or EF1 IK6, and after 10 days of culture in erythroid conditions: CD13+/GPA− (“myeloid”) cells and CD13−/GPA+ (“erythroid”) cells. The 2 sorted cell populations were cultured either in myeloid conditions or in erythroid conditions for 7 days, as shown in Figure 7A. On day 17, subcultured cells were analyzed for expression of GPA, CD33, CD13, and CD14 (Figure 7B,C).

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on GPA+ and CD13+ sorted cells that were subsequently cultured in erythroid or myeloid conditions. (A) CD34+ cells from CB were maintained in erythroid condition for 10 days. On day 3, cells were transduced with EF1 GFP and EF1 IK6 vectors. On day 10, untransduced and transduced cells were stained with CD13-PE and GPA-PC5 antibodies. CD13+/GPA− (CD13+ sorted cells) and CD13−/GPA+ (GPA+ sorted cells) were sorted by FACS. These 2 populations were replated in erythroid or myeloid conditions for 7 days, when subcultured cells were harvested, and living cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion and phenotyped for different cell-surface markers (erythroid marker, GPA; myeloid markers, CD14, CD13, and CD33). (B) Phenotype of erythroid cultured CD13+-sorted cells for CTRL (solid histogram), EF1 GFP (dashed line), and EF1 IK6 (bold line) conditions. (C) Phenotype of myeloid cultured GPA+-sorted cells for EF1 GFP (dashed line) and EF1 IK6 (bold line) conditions.

Effects of Ik6 overexpression on GPA+ and CD13+ sorted cells that were subsequently cultured in erythroid or myeloid conditions. (A) CD34+ cells from CB were maintained in erythroid condition for 10 days. On day 3, cells were transduced with EF1 GFP and EF1 IK6 vectors. On day 10, untransduced and transduced cells were stained with CD13-PE and GPA-PC5 antibodies. CD13+/GPA− (CD13+ sorted cells) and CD13−/GPA+ (GPA+ sorted cells) were sorted by FACS. These 2 populations were replated in erythroid or myeloid conditions for 7 days, when subcultured cells were harvested, and living cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion and phenotyped for different cell-surface markers (erythroid marker, GPA; myeloid markers, CD14, CD13, and CD33). (B) Phenotype of erythroid cultured CD13+-sorted cells for CTRL (solid histogram), EF1 GFP (dashed line), and EF1 IK6 (bold line) conditions. (C) Phenotype of myeloid cultured GPA+-sorted cells for EF1 GFP (dashed line) and EF1 IK6 (bold line) conditions.

In erythroid conditions, 77% and 80% of CTRL and EF1 GFP “myeloid” cells acquired GPA expression, respectively, whereas a smaller percentage (43%) of EF1 IK6 “myeloid” cells expressed GPA (Figure 7B). In EF1 IK6 cells, CD13 expression was maintained at 58% instead of 16% or 12% in CTRL or EF1 GFP populations, respectively. A total of 51% of EF1 IK6 cells expressed CD33 and 15% expressed CD14, whereas fewer CTRL and EF1 GFP cells expressed CD14 (3% and 1%, respectively) and CD33+ (5% and 8%, respectively). CTRL, EF1 GFP, and EF1 IK6 “erythroid” cells preserved GPA expression at 93%, 92%, and 97%, respectively, in erythroid conditions, as described for CB unsorted cells. Even in erythroid conditions, forced Ik6 expression was able to maintain myeloid markers from “myeloid” cells and to induce their expression on “erythroid” cells.

In myeloid conditions, “myeloid” cells remained CD13+, and percentages of GPA, CD14, CD13, and CD33 cells did not present significant differences between CTRL, EF1 GFP, and EF1 IK6 cells (data not shown). On the other hand, “erythroid” cells cultured in myeloid conditions for 7 days lost expression of GPA to acquire CD13 and CD33 expression: 43%, 51%, and 68% of initially CD13−/GPA+ cells were positive for GPA, CD13, and CD33, respectively, in the EF1 GFP protocol, as compared with 31%, 67%, and 86% were CD33+ in the EF1 Ik6 protocol (Figure 7C); rare EF1 GFP and EF1 IK6 cells expressed CD14 (1%). Thus, in myeloid conditions, Ik6 expression did not influence myeloid differentiation of “myeloid” cells, but amplified myeloid differentiation of “erythroid” cells.

Discussion

Our results provide some of the first evidence that expression of Ikaros is necessary for normal human erythroid differentiation.

First, we show that several functional isoforms of Ikaros are expressed at several stages of human erythroid differentiation, induced in an efficient in vitro culture system. Second, we demonstrate that transgenic Ik6 associates with endogenous Ik1—one of the major functional isoforms—in human hematopoietic differentiating cells, as shown by immunoprecipitation; our observation adds to previous studies demonstrating that interaction between Ik6 and Ik1 prevents activating or repressing effects of Ikaros on gene expression.8 Interaction of transgenic Ik6 with endogenous Ikaros proteins is associated with a decrease of the erythroid population differentiating from CB CD34+ progenitors; conversely, the residual myeloid population present in control cultures persists at a relatively unchanged level in cultures of Ik6-transduced cells.

The observed decrease in differentiating cell numbers is associated with an increase of cell death. This observation is consistent with the phenotype of Ikaros plastic mice, which showed dead cells in the fetal liver, and a decrease of differentiating and mature erythroid cells.18 These suggest a role for Ikaros in promoting human erythroid cell differentiation and survival.

Ikaros appears to be active in the early steps of human erythropoiesis. In fact, transgenic Ik6 overexpression induced a decrease of hemoglobin, which is associated with a decrease in GATA1 and its target genes: FOG1, EKLF, and EPOR by day 17 of culture. The decrease in formation of GATA1/FOG1 complexes could in turn induce a decrease of NFE2 and β-globin expression. GATA1, EKLF and NFE2 are also implicated in formation and activation of the β-globin LCR. Thus, Ikaros could indirectly induce the elaboration of an active structure that is associated with a transactivation of γ- and β-globin expression. Ikaros also induces expression and switch of globin genes during adult erythroid differentiation, which recapitulates the switch between γ- and β-globin genes (the so-called compressed switch). Indeed, in Ik6 mPB cells, no switch occurred: γ-globin remained the major expressed globin at the expense of β-globin. These observations are at least partly in agreement with previous murine studies looking at expression of a partial human β-globin locus (32 kb) in Ikaros null mice: these animals showed no defect in the expression of γ- and β-globin in the absence of Ikaros function, a discrepancy with our observations that could be due to interspecies differences or the use of a chimeric human/mouse model; however, they presented a blockade of the switch.15 This is because Ikaros is normally involved in the PYR complex fixed on the intergenic region. The low EKLF expression—a factor necessary to induce the switch40 —may also contribute to this defect.

Conversely, GATA2 and Ets-1 genes are overexpressed in Ik6 cells, while the level of junB gene decreases. In erythroid cells, GATA2 and Ets-1 are necessary in progenitors (GATA2 is a proliferative gene in early progenitors) but their overexpression interferes with terminal erythroid differentiation.41,42 junB is involved in erythroid gene expression and maturation.43 In our culture system, IK6 erythroid cells expressed c-kit and CD45, which are normally repressed during erythroid differentiation. Taken together, the decrease of expression of GATA1 and FOG1 and the remaining expression of c-kit and GATA2 are compatible with a blockade at the early steps of erythroid differentiation. Thus our results suggest that Ikaros is necessary for maturation of human erythroid cells.

These previous observations suggest that Ikaros positively regulates human erythroid differentiation at different stages. To address the question of a potential role of Ikaros in erythroid versus myeloid commitment, we took advantage of the persistence of a residual population of cells with myeloid markers in our culture system. Phenotypically defined “erythroid” or “myeloid” cells were sorted and subcultured either in “erythroid” or “myeloid” conditions in an attempt to induce “reverse differentiation.” “Erythroid” mock-transduced CB cells cultured in myeloid conditions partially lost expression of GPA and acquired myeloid gene expression; this reversion was accentuated by Ik6 forced expression. On the other hand, “myeloid” mock-transduced CB cells cultured in erythroid conditions largely lost CD13 expression and acquired GPA expression. Ik6 expression impairs this reversion, and most “myeloid” cells preserved expression of CD13 and CD33. Thus, while definitive commitment to the erythroid lineage does not occur in most control cells submitted to culture conditions designed to induce massive erytnroid differentiation, transgenic expression of Ik6 favors this phenomenon. These effects could be compared with that of the deletion of Pax5 expression: in these animals, cells were unable to differentiate in B lymphocytes, but reversed into the myeloid or T-cell pathways when these cells were cultured in specific conditions.44 This reversion was not possible with pro-B cells from normal Pax5+/+ mice that probably had reached a “no return” stage with the same phenotype.

It is noteworthy that the subpopulation of cells with myeloid makers did not expand in primary cultures as a consequence of Ik6 forced expression, although its relative importance increased due to the reduced numbers of erythroid cells. Molecular analyses logically detected a (relative) increase in the expression of certain myeloid genes, such as PU1, inflammatory caspases (caspase-1, -4, and -5), M-CSFR, and c-jun. These observations are in agreement with the augmentation of GM-CSFR gene expression in hematopoietic stem cells of deficient Ikaros mice.13 PU1-GATA1 antagonism is a well documented mechanism in myeloid versus erythroid differentiation.45 However, our preliminary results suggest that Ikaros does not significantly affect human myeloid differentiation.

In summary, our studies show for the first time that Ikaros plays a significant role in human erythropoiesis. It favors erythoid differentiation. As a hypothetical model, it is likely that Ikaros functions upstream of GATA1 in this process. Either Ikaros activates directly GATA1, a major gene in erythroid differentiation, or indirectly via the E2A/TAL/LMO2/Ldb complex that activates GATA1 with GATA2.

This study adds to the rare publications that describe the role of Ikaros in human hematopoiesis, especially in B lymphopoiesis and dendritic cell differentiation.35,46,47 The role of Ikaros in diseases has only been described for hematologic malignancies, mostly leukemias and lymphomas. The search for Ikaros deregulation in other diseases of the stem cell and erythroid compartments may provide additional information in the future.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank all personnel at the Beauregard and Bouchard maternity hospitals and at the Center de Thérapie Cellulaire et Génique for access to apheresis and cord blood samples. We also thank Thomas Moreau and Anne Marie Imbert for discussions and advice, Rémy Galindo at the Flow Cytometry Facility for his help during the conduct of these studies, and Patrice Dubreuil for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Institut Paoli-Calmettes, by the Canceropole PACA (Provence, Alpes, Côte d'Azur), and by Stem cell AIP contract Inserm no. A03188AS. M.D. is a recipient of a grant from the Conseil Régional PACA and the Société Française d'Hématologie (SFH).

Authorship

Contribution: M.D., C.C., and C.T. contributed to the conception, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; M.D. performed the majority of experiments with the technical assistance of F.B.; A.M. interpreted differentiation steps by analysis of morphology of cultured cells; and M.B. designed semiquantitative PCR plates.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cécile Tonnelle, Centre de Thérapie Cellulaire et Génique, Inserm UMR 599/Institut Paoli-Calmettes, 232 Bd Sainte Marguerite, 13273 Marseille Cedex 9, France; e-mail: tonnellec@marseille.fnclcc.fr.

![Figure 4. Effects of Ik6 overexpression on erythroid cell phenotypes. On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, CB untransduced and transduced cells were harvested and were analyzed for different cell-surface markers (erythroid markers: CD36, CD71, GPA and CD111; progenitor markers: CD117 [c-kit], CD34; human hematopoietic marker: CD45; and myeloid markers: CD33 and CD13) by flow cytometry. On day 20, CD36+, CD71+, GPA+, and CD111+ cell percentages (A) and numbers (B) are shown (mean ± SEM for 7 independent experiments). On day 20, percentages (C) and numbers (D) of CD117+, CD34+, CD45+, CD33+, and CD13+ cells are shown (means ± SEM for 4 to 7 independent experiments). The unchanged results on days 10 and 13 are shown in Table S1. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions; n.s. indicates not significant. Representative dot plots (E) show typical expression of CD13 and GPA, CD13 and CD33, CD13 and CD45, and CD13 and CD117 on day 20 for transduced and untransduced cell populations. Percentage in the quadrants is the percentage of cells present in the defined gate.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/3/10.1182_blood-2007-07-098202/6/m_zh80040812560004.jpeg?Expires=1768422785&Signature=cskkBlk5G73bVewrpS4H2q5sGqGhuAVe8velPSOVWux7Nn~JJnDEuFIchUw3nJOedmQOYUR2nQMzUAPH0pqkt-FmfVzz1scWEKTV9cKDikvPNWX4iqkQgb2~UKHmkhA3LoRMX5y9qzq7SG~o3064HmOLKK7ZCSYpw8HIsRnCAW6aLjKoRpM9Y9hM1KDVYgsbRYd1ydCcXoOr4Os5BAK-Tz-ZUck~2VHaeXJV0iiYQaHlToE5GgNSjZUjku45ujsTOo0dJKl9z~4FcdffeH-1Od71rZiZJys9EHyrTdTDs1clWPss40SXGJRE~XOoh~jHrXDtGEmEedGxpIApP91t8Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Effects of Ik6 overexpression on erythroid cell phenotypes. On days 10, 13, 17, and 20, CB untransduced and transduced cells were harvested and were analyzed for different cell-surface markers (erythroid markers: CD36, CD71, GPA and CD111; progenitor markers: CD117 [c-kit], CD34; human hematopoietic marker: CD45; and myeloid markers: CD33 and CD13) by flow cytometry. On day 20, CD36+, CD71+, GPA+, and CD111+ cell percentages (A) and numbers (B) are shown (mean ± SEM for 7 independent experiments). On day 20, percentages (C) and numbers (D) of CD117+, CD34+, CD45+, CD33+, and CD13+ cells are shown (means ± SEM for 4 to 7 independent experiments). The unchanged results on days 10 and 13 are shown in Table S1. *P < .05 using the Wilcoxon test compared with CTRL and EF1 GFP conditions; n.s. indicates not significant. Representative dot plots (E) show typical expression of CD13 and GPA, CD13 and CD33, CD13 and CD45, and CD13 and CD117 on day 20 for transduced and untransduced cell populations. Percentage in the quadrants is the percentage of cells present in the defined gate.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/3/10.1182_blood-2007-07-098202/6/m_zh80040812560004.jpeg?Expires=1768422786&Signature=usJ3da~mgEuAPgqFMHBdMZfTSTKbS1sk3ur1F8TZP~6DFXKfR5B-1hddXMZ1HwSSqrCG3iA1NTbilzjC5vSUZ-Fm7vwClVXFRPTfRXIq539lRpYrlU42SSmzf6ry9bPf6iBMIy-s6DpOor6rLjZ-Wee4o7mQYd-eVEgxR7tShY0bE796e6xyHMuahXX-F7peKfW2J-mzyM-efhdb14F5fkqjpd9eW~RTx5NuzF0QGaEmTB0q3CVLiXHvYVFuzPlNOfG5kRUUwKyLzFdVr7yBRdTvqdxx-UcwkaRu~7j9qQ29nYSLnJRjYX6K8JobEGldIIatXtc3VBjhvLpjMqCSeA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)