Abstract

B-cell development is orchestrated by complex signaling networks. Rap1 is a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins and has 2 isoforms, Rap1a and Rap1b. Although Rap1 has been suggested to have an important role in a variety of cellular processes, no direct evidence demonstrates a role for Rap1 in B-cell biology. In this study, we found that Rap1b was the dominant isoform of Rap1 in B cells. We discovered that Rap1b deficiency in mice barely affected early development of B cells but markedly reduced marginal zone (MZ) B cells in the spleen and mature B cells in peripheral and mucosal lymph nodes. Rap1b-deficient B cells displayed normal survival and proliferation in vivo and in vitro. However, Rap1b-deficient B cells had impaired adhesion and reduced chemotaxis in vitro, and lessened homing to lymph nodes in vivo. Furthermore, we found that Rap1b deficiency had no marked effect on LPS-, BCR-, or SDF-1–induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and AKT but clearly impaired SDF-1–mediated activation of Pyk-2, a key regulator of SDF-1–mediated B-cell migration. Thus, we have discovered a critical and distinct role of Rap1b in mature B-cell trafficking and development of MZ B cells.

Introduction

B-cell development involves a series of stages defined by the sequential rearrangement and expression of heavy (H)- and light (L)-chain immunoglobulin genes as well as by the appearance of other cell-surface proteins.1,2 The H-chain locus rearranges V, D, and J segments first in the pro-B cells. A successful VDJH rearrangement leads to the expression of a μH chain, which in combination with a surrogate light chain forms the pre-B-cell receptor (pre-BCR).3-5 Signals emanating from the pre-BCR control pro- to pre-B-cell transition. Subsequently, pre-B cells undergo rearrangement of L-chain V and J gene segments. A successfully rearranged L chain, in combination with the previously rearranged H chain, generates a surface IgM form of the BCR. B cells with a functional BCR quickly progress into immature B cells and emerge from bone marrow (BM) into the spleen.1,2 Maturation of newly formed immature B cells in the spleen involves several steps that are regulated by signals from the BCR.6,7 Immature B cells from BM emerge into the spleen as transitional B cells of type 1 (T1). T1 B cells develop into the transitional B cells of type 2 (T2). Ultimately, T2 B cells give rise to 2 subsets of long-lived mature B cells, follicular (FO) B cells and marginal zone (MZ) B cells. The recirculating FO B cells localize to the B-lymphoid follicles of the spleen and lymph node,8 whereas the mostly nonrecirculating MZ B cells come to reside primarily in the marginal zones of the splenic lymphoid nodules.9-11 A third subset of mature B cells, self-renewing B1 B cells, are derived from fetal liver B-cell progenitors and are enriched in the peritoneal and pleural cavities.12 In addition to signals emanating from the BCR, signals derived from chemokines regulate development and compartmentalization of different subsets of mature B cells.13,14 Defects in chemokine signaling often reduce B-cell chemotaxis, leading to an impairment of the development of mature B-cell subsets.15-17

Rap1 is a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins.18,19 Rap1 has 2 isoforms, Rap1a and Rap1b, coded by distinct genes.18 Like other small GTP-binding proteins, GTP-bound Rap1 is an active form, whereas the GDP-bound form is an inactive form. Activation of Rap1 is regulated by specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors that promote the dissociation of GDP to facilitate GTP loading.18,19 The termination of Rap1GTP activity is regulated by Rap1 GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Rap1GTP is able to regulate activation of all 3 MAPKs.20-26 In some cells, Rap1GTP may competitively interfere with Ras-mediated ERK activation.20 However, Rap1GTP is also able to directly activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway by recruiting phosphorylated B-raf.21 In addition, Rap1GTP induces MEK3/6-mediated p38 activation in a Ras-independent manner.22,23 The small GTPases have also been shown to be involved in the activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK).24-26 Moreover, Rap1 shares 100% homology in the effector domain with Ras and is expected to bind Ras effectors, such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) p110 subunit,18 and studies have shown that the Rap1 is able to regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway.27-30

Rap1 is activated by a variety of receptors, including receptors for antigens, growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, heterotrimeric G-protein–coupled receptors, and cell-adhesion molecules.31 Studies have shown that Rap1 is involved in the regulation of multiple cellular processes, including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation.18,32,33 Previous studies indicate that Rap1 might play an important role in B-cell adhesion, migration, and BCR repertoire.34-38 For instance, mice deficient in SPA-1, a Rap1GAP, show an age-dependent increase in B1a cells producing anti-double-stranded DNA antibody and abnormal acceleration of Vκ gene recombination, resulting in lupus-like nephritis and an altered Vκ gene repertoire, respectively.35 Nonetheless, no direct evidence demonstrates a role of Rap1 in B-cell biology. With Rap1b-deficient mice, we have discovered a critical and distinct role of Rap1b in mature B-cell trafficking to lymph nodes and development of MZ B cells in the spleen.

Methods

All mouse procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Mice

Rap1b-deficient mice were generated as described previously.39

In vivo bromodeoxyuridine labeling assay

The in vivo bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) staining assay was performed as described previously.40 In brief, 8- to 10-week-old mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in 0.2 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 12-hour intervals for 4 days. The splenocytes from BrdU-treated mice were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7-conjugated anti-B220, allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-IgM, PE-conjugated anti-CD21, biotin-conjugated anti-CD23, and subsequently with PE-Cy5.5-labeled streptavidin. Finally, the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-BrdU (monoclonal; BD Biosciences). The degree of BrdU-positivity in the gated B-cell subpopulations, T1, T2, FO, and MZ, was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

In vitro migration assay

Purified splenic B cells (5 × 105) from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were suspended in 100 μL RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and added to an upper chamber of a 24-well tissue transwell plate (5-μm pore size; Costar; Corning Life Sciences, Acton, MA). Stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1; 100 ng/mL), B lymphocyte chemokine (BLC; 500 ng/mL), or secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC; 500 ng/mL) was added to the medium in the bottom chamber. Medium alone was used as a control. After a 2.5-hour incubation at 37°C, migrated cells were collected and stained with PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-B220, FITC-conjugated anti-CD21, PE-conjugated anti-CD23, and APC-conjugated anti-IgM antibodies. Duplicates of input and migrated total B cells and subsets of B cells were quantified by FACS.

Adhesion assay

Adhesion assay was performed as described previously.41 In brief, 96-well plates were coated with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1; 1 μg/mL, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in PBS at 4°C overnight, washed 3 times with PBS, and blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Purified splenic B cells from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 0.5% BSA at 106/mL. Cells (105 in 100 μL; triplicates) were loaded in wells and left to adhere for 30 minutes at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing 6 times with HBSS with 0.5% BSA. Adherent cells were released by incubating for 15 minutes on ice in RPMI 1640 medium with 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Subsequently, cells were stained with PE Cy7-conjugated anti-B220, FITC-conjugated anti-CD21, PE-conjugated anti-CD23, and APC-conjugated anti-IgM antibodies. Input and adhered total B cells and subsets of B cells were quantified by FACS.

Immunizations

Immunization and serum titer analyses were performed as described previously.40,42 In brief, 2- to 5-month-old wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 50 μg T-independent (TI) antigen trinitrophenylated Ficoll (TNP-Ficoll; Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA) or 50 μg T-dependent (TD) antigen nitrophenylated chicken γ-globulin (NP-CGG; Biosearch). Serum was collected from mice immunized with TNP-Ficoll 7 days after immunization and from mice immunized with NP-CGG 14 days after immunization. Antigen-specific antibodies were determined by ELISA.

Western blot analysis

FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) or MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) B cells were sorted from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells (5 × 106/mL) were stimulated with anti-IgM (10 μg/mL, for FO B cells; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 μg/mL, for MZ B cells) at 37°C for the times indicated in Figure 7. For chemokine-induced Pyk-2 activation assay, total splenic B cells were purified using anti-B220-coated magnetic beads and then stimulated with SDF-1 (100 ng/mL) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Rabbit polyclonal anti-ERK (sc-093), anti-JNK2 (sc-572), anti-p38 (sc-535), anti-Rap1 (sc-363), anti–phospho-Pyk2 (pTyr402, sc-11 767), mouse monoclonal anti–phospho-ERK (pThr202/pTyr204, sc-7383), and goat polyclonal anti-Pyk2 (sc-1514) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Akt (phospho-Ser473, no. 9271), rabbit monoclonal anti-Rap1b (no. 2326), mouse monoclonal anti–phospho-JNK (pThr183/pTyr185, no. 9255) and anti–phospho-p38 (pThr180/pTyr182, no. 9216) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by unpaired Student t test.

Results

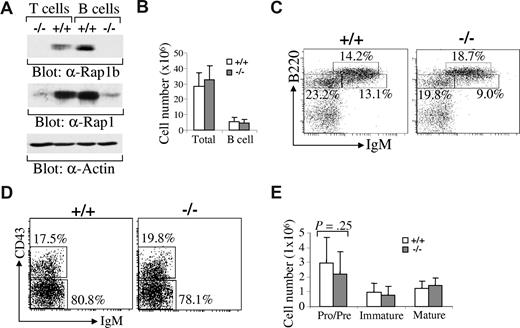

Predominant expression of Rap1b in B lymphocytes

Rap1 has 2 isoforms, Rap1a and Rap1b.18 We examined the expression levels of Rap1b relative to Rap1a in B cells. Splenic B cells were sorted from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then subjected to direct Western blot with anti-Rap1b antibodies (which specifically recognize Rap1b) or anti-Rap1 antibodies (which recognize both Rap1a and Rap1b). Rap1b was expressed in wild-type B cells but not in Rap1b-deficient B cells (Figure 1A). Total Rap1 expression in B cells was dramatically reduced in Rap1b-deficient B cells relative to wild-type B cells, demonstrating that the predominant isoform of Rap1 in B cells is Rap1b instead of Rap1a (Figure 1A). Likewise, Rap1b was expressed in T cells and was the predominant isoform of Rap1 in T cells (Figure 1A). Thus, Rap1b was the predominant isoform of Rap1 in lymphocytes.

Predominant expression of Rap1b isoform in B cells and slight impairment of early B-cell development in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Expression of Rap1a and Rap1b in wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) T and B cells. Based on the expression of B220 and Thy1.2, splenic T and B cells were sorted from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Rap1b, anti-Rap1 or anti-Actin antibodies. (B) The numbers of total BM cells and total BM B cells in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 12 mice of each genotype. (C) B-cell development in BM of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. BM cells from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD43, and anti-IgM antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid population. Data are representative of 12 mice per genotype. (D) Pro- and pre-B cells in BM of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+IgM− population. Data are representative of 12 mice per genotype. (E) The numbers of pro-/pre-, immature, and mature B cells in BM of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 12 mice of each genotype.

Predominant expression of Rap1b isoform in B cells and slight impairment of early B-cell development in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Expression of Rap1a and Rap1b in wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) T and B cells. Based on the expression of B220 and Thy1.2, splenic T and B cells were sorted from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Rap1b, anti-Rap1 or anti-Actin antibodies. (B) The numbers of total BM cells and total BM B cells in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 12 mice of each genotype. (C) B-cell development in BM of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. BM cells from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD43, and anti-IgM antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid population. Data are representative of 12 mice per genotype. (D) Pro- and pre-B cells in BM of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+IgM− population. Data are representative of 12 mice per genotype. (E) The numbers of pro-/pre-, immature, and mature B cells in BM of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 12 mice of each genotype.

Development of early B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice

The number of total BM cells and the population of total B cells (B220+) in BM from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were comparable (Figure 1B). The population of pro-/pre-B cells (B220+IgM−) was slightly but not significantly (P = .25) reduced in BM from Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type mice (Figure 1C,E). In gated IgM− pro-/pre-B cells, the percentages of pro-B cells (B220+CD43+IgM−) and pre-B cells (B220+CD43−IgM−) were comparable between wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice (Figure 1D). In addition, the population of immature (B220+IgM+) and mature (B220hiIgM+) B cells were comparable between wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice (Figure 1C,E). It is noteworthy that development of T cells in thymus was normal in Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type mice (data not shown). Therefore, in the absence of Rap1b, early B-cell development was largely normal.

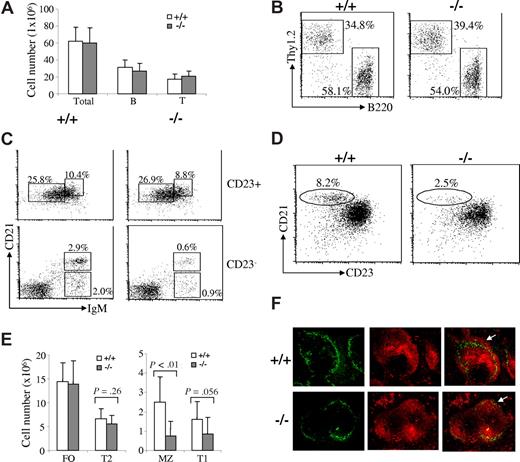

MZ B-cell population in Rap1b-deficient mice is markedly reduced

We also examined B-cell maturation in the spleen of Rap1b-deficient mice. The number of total splenocytes in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice was comparable (Figure 2A). Splenic B and T cell populations in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were comparable (Figure 2A,B).

Marked reduction of MZ B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) The numbers of total splenocytes and total splenic B and T cells in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 10 mice of each genotype. (B) B and T cells in the spleens of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Splenocytes from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-B220 and anti-Thy1.2 antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid population. Data are representative of 10 mice per genotype. (C) T1, T2, FO, and MZ B cells in the spleens of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Splenocytes from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21 and anti-CD23 antibodies. In cells gated on CD23+, T2 (CD23+CD21hiIgMhi) and FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) B cells are shown. In cells gated on CD23−, T1 (CD23−CD21loIgMhi) and MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) B cells are shown. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 10 mice per genotype. (D) MZ B cells in the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Splenocytes from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. In cells gated on B220+, MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) are shown. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+ lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 10 mice per genotype. (E) The numbers of T1, T2, FO, and MZ B cells in the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 10 mice of each genotype. (F) Immunofluorescence histochemical analysis of MZ B cells in the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Frozen splenic sections derived from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-MOMA-1 (green) and anti-IgM (red). MZ B-cell layer external to the ring of metallophilic macrophages is indicated by arrows. The data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Marked reduction of MZ B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) The numbers of total splenocytes and total splenic B and T cells in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 10 mice of each genotype. (B) B and T cells in the spleens of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Splenocytes from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-B220 and anti-Thy1.2 antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid population. Data are representative of 10 mice per genotype. (C) T1, T2, FO, and MZ B cells in the spleens of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Splenocytes from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21 and anti-CD23 antibodies. In cells gated on CD23+, T2 (CD23+CD21hiIgMhi) and FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) B cells are shown. In cells gated on CD23−, T1 (CD23−CD21loIgMhi) and MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) B cells are shown. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 10 mice per genotype. (D) MZ B cells in the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Splenocytes from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. In cells gated on B220+, MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) are shown. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+ lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 10 mice per genotype. (E) The numbers of T1, T2, FO, and MZ B cells in the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown are obtained from 10 mice of each genotype. (F) Immunofluorescence histochemical analysis of MZ B cells in the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Frozen splenic sections derived from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-MOMA-1 (green) and anti-IgM (red). MZ B-cell layer external to the ring of metallophilic macrophages is indicated by arrows. The data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Based on the expression of IgM, CD21, and CD23, splenic B cells can be separated into CD23+ and CD23− populations to define the different subsets of immature and mature B cells.9 Among the populations of CD23+-gated cells, FO (CD23+CD21int IgMlo) B cells in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were comparable (Figure 2C,E). T2 (CD23+CD21hiIgMhi) B cells were slightly decreased in Rap1b-deficient compared with wild-type mice, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .26) (Figure 2C,E). In CD23−-gated cells, the population of T1 B cells (CD23−CD21loIgMhi) was slightly reduced (P = .056) whereas the population of MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was markedly reduced (P < .01) in Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type mice (Figure 2C,E). In addition, the MZ B-cell population can be recognized as B220+CD21hiCD23lo cells based on expression of the B220, CD21, and CD23 markers. In B220+-gated cells, MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) were markedly decreased in Rap1b-deficient mice (Figure 2D).

The severe reduction of MZ B cells was further confirmed by immunofluorescent staining. Frozen spleen sections from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with rhodamine (tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM and FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse metallophilic macrophages antibody-1 (MOMA-1). The ring of metallophilic macrophages permits visualization of the border between the follicular and marginal zones. In agreement with the flow cytometric results, the width of the MZ B-cell area, which lies external to the ring of metallophilic macrophages, was narrowly detectable in the spleen derived from Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type mice (Figure 2F). The distribution of MOMA-1+ metallophilic macrophages was unimpaired, indicating the normal structure of the marginal zone in Rap1b-deficient mice (Figure 2F). It is noteworthy that the splenic white-pulp in Rap1b-deficient mice had a normal structure and an amount of B cells comparable to that in wild-type mice (Figure 2F). Those results, together with the FACS analysis results that the total B cells and subsets of B cells (T1, T2, and FO) were largely normal in the spleens of Rab1b-deficient mice (Figure 2A-E) suggest that Rap1b-deficient B cells enter into the splenic white-pulp cords normally. These results also confirm the dramatic reduction of MZ B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice despite a normal follicular architecture.

The self-renewing mature B1 B cells primarily reside in the peritoneal and pleural cavities. We examined the effect of Rap1b deficiency on the development of B1 cells. Based on expression of CD5 and B220, B cells in the peritoneal and pleural cavities can be divided into B1a (B220loCD5+), B1b (B220loCD5−), and B2 (B220hiCD5−) B cells.43 In peritoneal lymphocytes, the populations of B1a and B1b cells were slightly, but not significantly, increased in Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type mice, whereas B2 cells in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were comparable (Figure 3A,B). Therefore, Rap1b deficiency did not impair the development of B1 B cells.

Normal B1 B cells, reduced lymph node B cells, and an intrinsic MZ B-cell defect in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) B1 B cells in the peritoneal cavities of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Peritoneal cells from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-B220 and anti-CD5 antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 6 mice per genotype. (B) The percentages of B1a, B1b, and B2 B cells in the peritoneal cells of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown were obtained from 6 mice of each genotype. (C) The numbers of B and T cells in the lymph nodes of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Lymphocytes from inguinal (ILN), axillary (ALN), and mesenteric (MLN) lymph nodes of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-B220 and anti-thy1.2 antibodies, and the numbers of B and T cells in ILN, ALN and MLN were determined. Data shown were obtained from 14 mice of each genotype for ILN and ALN and 12 mice of each genotype for MLN. (D) MZ B-cell defect in Rap1b-deficient mice is B-cell intrinsic. Sublethally irradiated JAK3-deficient mice were transplanted with BM from wild-type (Rap1b+/+ + JAK3−/−) and Rap1b-deficient (Rap1b−/− + JAK3−/−) mice. Sublethally irradiated JAK3-deficient mice without BM transplantation (JAK3−/−) were used as a negative control. Eight weeks after transplantation, splenocytes from recipient mice were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. In B220+-gated cells, MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) are shown. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+ lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 4 recipients transplanted with Rap1b+/+ BM, and 5 recipients transplanted with Rap1b−/− BM. The mean (± SD) for the data from all of the recipients in each type of transplantation has been summarized in a bar graph (right).

Normal B1 B cells, reduced lymph node B cells, and an intrinsic MZ B-cell defect in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) B1 B cells in the peritoneal cavities of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Peritoneal cells from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-B220 and anti-CD5 antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 6 mice per genotype. (B) The percentages of B1a, B1b, and B2 B cells in the peritoneal cells of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Data shown were obtained from 6 mice of each genotype. (C) The numbers of B and T cells in the lymph nodes of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Lymphocytes from inguinal (ILN), axillary (ALN), and mesenteric (MLN) lymph nodes of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stained with anti-B220 and anti-thy1.2 antibodies, and the numbers of B and T cells in ILN, ALN and MLN were determined. Data shown were obtained from 14 mice of each genotype for ILN and ALN and 12 mice of each genotype for MLN. (D) MZ B-cell defect in Rap1b-deficient mice is B-cell intrinsic. Sublethally irradiated JAK3-deficient mice were transplanted with BM from wild-type (Rap1b+/+ + JAK3−/−) and Rap1b-deficient (Rap1b−/− + JAK3−/−) mice. Sublethally irradiated JAK3-deficient mice without BM transplantation (JAK3−/−) were used as a negative control. Eight weeks after transplantation, splenocytes from recipient mice were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. In B220+-gated cells, MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) are shown. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+ lymphoid populations. Data are representative of 4 recipients transplanted with Rap1b+/+ BM, and 5 recipients transplanted with Rap1b−/− BM. The mean (± SD) for the data from all of the recipients in each type of transplantation has been summarized in a bar graph (right).

Reduced lymphocytes in the lymph nodes from Rap1b-deficient mice

Furthermore, we examined the B-cell population in the lymph nodes of Rap1b-deficient mice. It is noteworthy that the B-cell population was markedly reduced in the lymph nodes of Rap1b-deficient mice compared with that in wild-type mice (Figure 3C). The reduction was 45% in inguinal (P < .05), 50% in axillary (P = .01), and 30% in mesenteric (P < .05) lymph nodes (Figure 3C). The T cell population was also decreased in the lymph nodes of Rap1b-deficient mice, but this did not reach statistical significance (P > .05) (Figure 3C). These data indicate that Rap1b deficiency affects B-cell homing to peripheral and mucosal lymph nodes.

The MZ B-cell defect in Rap1b-deficient mice is B-cell autonomous

To determine whether the reduction of MZ B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice is the result of an intrinsic abnormality of the B cells, we examined the ability of Rap1b-deficient BM cells to develop into MZ B cells in B-cell–null JAK3-deficient mice.44,45 We transplanted equal numbers of BM cells from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice into sublethally irradiated JAK3-deficient mice. Eight weeks after transplantation, the recipients were analyzed. MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) were markedly reduced in the JAK3-deficient recipients that received Rap1b-deficient BM cells compared with those in the recipients that received wild-type BM cells (Figure 3D), similar to the defect that was found in Rap1b-deficient mice (Figure 2D). These data demonstrate that the MZ B-cell defect in Rap1b-deficient mice is B-cell autonomous.

Normal survival and proliferation of Rap1b-deficient B cells

To determine whether the reduction of MZ B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice is due to impaired cell survival or proliferation, we examined the rate of apoptosis and proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells. First, we stained splenocytes from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies, followed by TUNEL assay. Naive Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) had a similarly low rate of apoptosis relative to wild-type MZ B cells (Figure 4A,B). Likewise, naive Rap1b-deficient T1, T2, and FO B cells had a low rate of apoptosis comparable with the corresponding wild-type B-cell subpopulations (data not shown). Furthermore, after anti-IgM stimulation, Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells displayed a degree of BCR-induced apoptosis similar to that of wild-type cells (data not shown).

Normal apoptosis and proliferation of B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Normal apoptosis in naive Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells. Splenocytes from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. The degree of TUNEL positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate TUNEL-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 3 independent analyses. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentages of TUNEL-positive MZ B cells from panel A (3 mice of each genotype). (C) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells in vivo. Wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were injected with BrdU every 12 hours for 4 days. Splenocytes from the mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Cells were then permeabilized, fixed, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU. The degree of BrdU positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate BrdU-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 2 mice per genotype. (D) Statistical analysis of the percentages of BrdU-positive MZ B cells from panel C (2 mice of each genotype). (E) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells in response to LPS in vitro. MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) and FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) B cells were sorted from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient splenic mature B cells in response to LPS, anti-IgM, or anti-IgM plus IL-4 in vitro. Splenic mature B cells were purified from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS, anti-IgM or anti-IgM plus IL-4 for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Normal apoptosis and proliferation of B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Normal apoptosis in naive Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells. Splenocytes from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. The degree of TUNEL positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate TUNEL-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 3 independent analyses. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentages of TUNEL-positive MZ B cells from panel A (3 mice of each genotype). (C) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells in vivo. Wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were injected with BrdU every 12 hours for 4 days. Splenocytes from the mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Cells were then permeabilized, fixed, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU. The degree of BrdU positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate BrdU-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 2 mice per genotype. (D) Statistical analysis of the percentages of BrdU-positive MZ B cells from panel C (2 mice of each genotype). (E) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells in response to LPS in vitro. MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) and FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) B cells were sorted from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient splenic mature B cells in response to LPS, anti-IgM, or anti-IgM plus IL-4 in vitro. Splenic mature B cells were purified from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS, anti-IgM or anti-IgM plus IL-4 for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

To directly assess the proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells, we used an in vivo BrdU labeling assay. After administration of BrdU, the BrdU-labeling rates of the B-cell subpopulations in the mutant or wild-type mice were determined by FACS analysis. Rap1b-deficient and wild-type MZ B cells exhibited comparable BrdU-incorporating rates (Figure 4C,D). Likewise, Rap1b-deficient T1, T2, and FO B cells had BrdU-incorporating rates similar to those of the corresponding wild-type B-cell subpopulations (data not shown). Furthermore, we examined the in vitro proliferation of Rap1b-deficient B cells in response to LPS and anti-IgM by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. MZ and FO mature B cells were sorted based on the expression of IgM, CD21, and CD23 and then stimulated with LPS. The [3H]thymidine incorporation rates of Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells and corresponding wild-type B cells in response to LPS stimulation were comparable (Figure 4E). The [3H]thymidine incorporation rate of the purified Rap1b-deficient splenic mature B cells (B220+AA4.1−) in response to stimulation of LPS was also similar to that of corresponding wild-type cells (Figure 4F). In addition, the [3H]thymidine incorporation rate of the purified Rap1b-deficient splenic mature B cells in response to stimulation of anti-IgM plus IL-4 was similar to that of corresponding wild-type cells (Figure 4F). Cell cycle analysis also demonstrated that after LPS or anti-IgM stimulation, Rap1b-deficient mature B cells entered S and G2/M phases at the same rate as wild-type mature B cells (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the lack of Rap1b did not affect survival and proliferation of B cells.

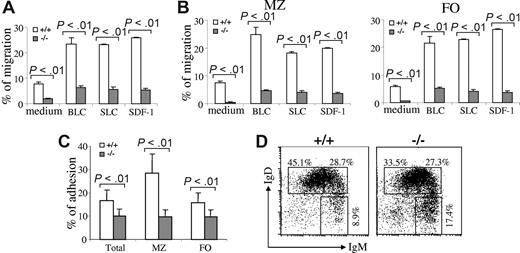

Impaired adhesion and migration of Rap1b-deficient B cells

A defect in the B-cell adhesion, migration, and retention is able to reduce MZ B cells in the spleen.15,16,41,46 To determine whether there is a defect in the migration of Rap1b-deficient B cells, we examined the migration of the mutant B cells in response to the chemokines, including BLC/CXCL13, SLC/CCL21, and SDF-1/CXCL12. Purified splenic B cells from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were subjected to an in vitro transwell chemotaxis assay. Input and migrated B cells were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies, and the numbers of B-cell subpopulations were quantified by FACS. The migration of Rap1b-deficient total splenic B cells toward BLC, SLC, or SDF-1 was markedly decreased compared with that of wild-type total splenic B cells (P < .01; Figure 5A). Furthermore, the migration of Rap1b-deficient FO and MZ B cells to BLC, SLC, or SDF-1 was also markedly reduced relative to that of the corresponding wild-type B cells (P < .01; Figure 5B). Therefore, Rap1b deficiency impaired B-cell migration in response to chemokines, including BLC, SLC, and SDF-1.

Impaired migration and adhesion of Rap1b-deficient B cells. (A) Chemokine-mediated migration of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells. Purified total splenic B cells from wild-type (+/+) or Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were subjected to in vitro transwell migration assays to BLC, SLC, SDF-1, and medium alone. Duplicates of input cells (from aliquots) and migrated cells were quantified by flow cytometry. The number of cells migrated is expressed as the percentage of total input cells. Data shown are from 3 independent experiments for BLC and SLC and 5 independent experiments for SDF-1. (B) Chemokine-mediated migration of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells. Total splenocytes from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were subjected to in vitro transwell migration assays to BLC, SLC, SDF-1, and medium alone. Duplicates of input cells (from aliquots) and migrated cells were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD21, anti-CD23, and anti-IgM antibodies. Input and migrated MZ and FO B cells were quantified by flow cytometry. The numbers of MZ and FO cells migrated are expressed as the percentages of input MZ and FO B cells, respectively. Data shown are from 3 independent experiments for BLC and SLC and 5 independent experiments for SDF-1. (C) Adhesion of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells to VCAM-1. Purified total splenic B cells from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were allowed to adhere to VCAM-1–coated 96-well plates. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing. Triplicate of input and adherent cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. The adhesion of total B cells, MZ, and FO B cells was calculated as a percentage of total, MZ, or FO B cell input, respectively. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) The proportions of immature and mature B cells in the peripheral blood of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Red cell–depleted blood cells were stained with anti-B220, anti-IgM, and anti-IgD antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+ B cells. Data are representative of 6 mice per genotype.

Impaired migration and adhesion of Rap1b-deficient B cells. (A) Chemokine-mediated migration of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells. Purified total splenic B cells from wild-type (+/+) or Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were subjected to in vitro transwell migration assays to BLC, SLC, SDF-1, and medium alone. Duplicates of input cells (from aliquots) and migrated cells were quantified by flow cytometry. The number of cells migrated is expressed as the percentage of total input cells. Data shown are from 3 independent experiments for BLC and SLC and 5 independent experiments for SDF-1. (B) Chemokine-mediated migration of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells. Total splenocytes from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were subjected to in vitro transwell migration assays to BLC, SLC, SDF-1, and medium alone. Duplicates of input cells (from aliquots) and migrated cells were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD21, anti-CD23, and anti-IgM antibodies. Input and migrated MZ and FO B cells were quantified by flow cytometry. The numbers of MZ and FO cells migrated are expressed as the percentages of input MZ and FO B cells, respectively. Data shown are from 3 independent experiments for BLC and SLC and 5 independent experiments for SDF-1. (C) Adhesion of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells to VCAM-1. Purified total splenic B cells from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were allowed to adhere to VCAM-1–coated 96-well plates. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing. Triplicate of input and adherent cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. The adhesion of total B cells, MZ, and FO B cells was calculated as a percentage of total, MZ, or FO B cell input, respectively. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) The proportions of immature and mature B cells in the peripheral blood of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Red cell–depleted blood cells were stained with anti-B220, anti-IgM, and anti-IgD antibodies. Percentages indicate cells in the gated B220+ B cells. Data are representative of 6 mice per genotype.

Next, we examined adhesion of Rap1b-deficient B cells to VCAM-1. Purified splenic B cells from wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice were incubated with VCAM-1–coated plates. Input and adhered B cells were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies, and the numbers of total, MZ, and FO B cells were quantified by FACS. It is noteworthy that adhesion levels of Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells to VCAM-1 were reduced compared with those of wild-type B cells (P < .01; Figure 5C). Furthermore, Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells exhibited a markedly decreased adhesion to VCAM-1 relative to the wild-type corresponding B cells (P < .01; Figure 5C). Therefore, Rap1b deficiency impaired MZ and FO B-cell adhesion to VCAM-1.

Moreover, the proportion of mature B cells (IgMloIgDhi) was decreased, whereas the proportion of newly formed immature B cells (IgMhiIgDlo) was increased in the blood of Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type mice (Figure 5D). These results suggest that trafficking defects are present in newly formed Rap1b-deficient B cells in vivo, and the defect in trafficking hinders B-cell maturation because of impaired homing to lymphoid organs.

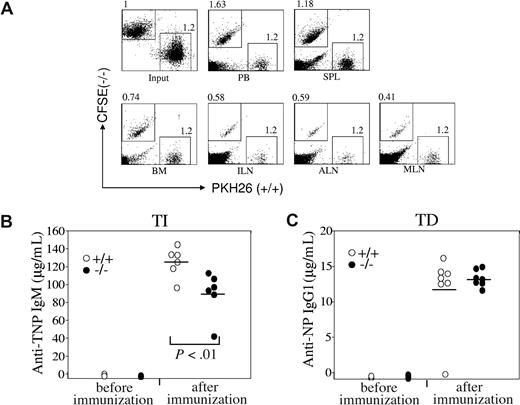

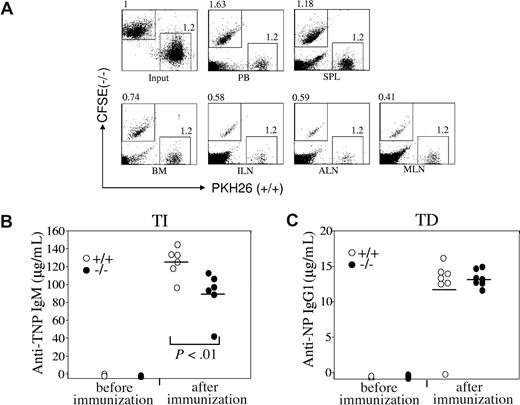

B-cell homing to the lymph nodes in Rap1b-deficient mice is impaired

Chemokines play critical roles in B-cell homing to lymph nodes,13 and we next directly examined the homing ability of Rap1b-deficient B cells in vivo. Mature splenic B cells were purified from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice and stained with PKH26 and carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE), respectively. Subsequently, equal numbers of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells were intravenously injected into wild-type mice. After adoptive transfer, the ratios of Rap1b-deficient B cells to wild-type B cells in the lymphoid organs of the recipients were determined by FACS analysis. The ratios of Rap1b-deficient B cells to wild-type B cells in the lymph nodes were markedly decreased compared with that of input (Figure 6A). The reduction was 40% in inguinal, 40% in axillary, and 60% in mesenteric lymph nodes (Figure 6A). The ratio of Rap1b-deficient B cells to wild-type B cells in BM was also decreased compared with that of input (Figure 6A). Consistent with the impaired homing of Rap1b-deficient B cells to lymph nodes and BM, the ratio of Rap1b-deficient B cells to wild-type B cells in the blood was increased compared with that of input (Figure 6A). It is noteworthy that the ratio of Rap1b-deficient B cells to wild-type B cells in the spleen was slightly increased compared with that of input (Figure 6A). Therefore, these data demonstrate that Rap1b deficiency impairs B-cell homing to the lymph nodes, which is in agreement with the finding that B cells were apparently reduced in the lymph nodes of Rap1b-deficient mice.

Impaired homing of Rap1b-deficient B cells to the lymph nodes in vivo and slightly impaired immune response to TI-specific antigens in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Homing of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells to lymph nodes in vivo. Purified splenic B cells from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were labeled with PKH26 and CFSE, respectively. Equal numbers of labeled wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells were mixed and injected into the tail veins of C57BL/6 wild-type mice. After 1 hour, mononuclear cells from peripheral blood (PB), spleen (SPL), BM, and lymph nodes, including inguinal (ILN), axillary (ALN), and mesenteric (MLN), were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Each experiment contains 2 recipients. (B) Immune response to TI-specific antigens in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Wild-type (n = 6) and Rap1b-deficient (n = 6) mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the TI antigen, TNP-Ficoll. 7 days after immunization, the titers of TNP-specific IgM in sera were determined by ELISA. Mean values are indicated with black bars. (C) Immune response to TD-specific antigens in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Wild-type (n = 7) and Rap1b-deficient (n = 7) mice were immunized intraperitoneally with TD antigen, NP-CGG. Fourteen days after immunization, the titers of NP-specific IgG1 in sera were determined by ELISA. Mean values are indicated with black bars.

Impaired homing of Rap1b-deficient B cells to the lymph nodes in vivo and slightly impaired immune response to TI-specific antigens in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Homing of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells to lymph nodes in vivo. Purified splenic B cells from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were labeled with PKH26 and CFSE, respectively. Equal numbers of labeled wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells were mixed and injected into the tail veins of C57BL/6 wild-type mice. After 1 hour, mononuclear cells from peripheral blood (PB), spleen (SPL), BM, and lymph nodes, including inguinal (ILN), axillary (ALN), and mesenteric (MLN), were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Each experiment contains 2 recipients. (B) Immune response to TI-specific antigens in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Wild-type (n = 6) and Rap1b-deficient (n = 6) mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the TI antigen, TNP-Ficoll. 7 days after immunization, the titers of TNP-specific IgM in sera were determined by ELISA. Mean values are indicated with black bars. (C) Immune response to TD-specific antigens in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. Wild-type (n = 7) and Rap1b-deficient (n = 7) mice were immunized intraperitoneally with TD antigen, NP-CGG. Fourteen days after immunization, the titers of NP-specific IgG1 in sera were determined by ELISA. Mean values are indicated with black bars.

Immune response to TI antigen is slightly impaired in Rap1b-deficient mice

Our studies revealed nonmanipulated Rap1b-deficient mice had the same levels of IgM, IgA, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 in their sera as wild-type mice (data not shown). Furthermore, we examined the role of Rap1b in the humoral immune responses to TI and TD antigen challenge. Rap1b-deficient or wild-type mice were immunized with a TI antigen TNP-Ficoll or a TD antigen NP-CGG. After the immunization, serum titers of antigen-specific antibodies were examined. Wild-type mice produced antigen-specific antibodies; IgM was a major isotype in response to TNP-Ficoll (Figure 6B), and IgG1 was the major isotype in response to NP-CGG (Figure 6C). It is noteworthy that Rap1b-deficient mice produced slightly but significantly (P < .01) less TNP-specific IgM in response to TNP-Ficoll than wild-type mice (Figure 6B). In contrast, Rap1b-deficient and wild-type mice generated comparable amounts of NP-specific IgG1 in response to NP-CGG (Figure 6C). Therefore, Rap1b-deficient mice have slightly impaired TI immune response but normal TD immune response.

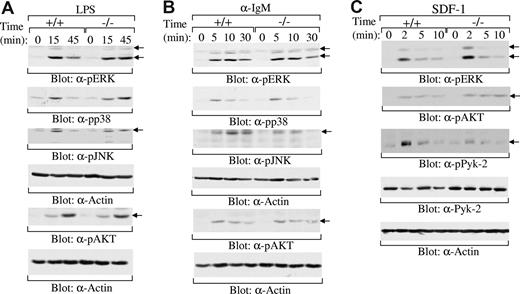

Rap1b-deficiency impairs SDF-1-induced Pyk-2 activation

Previous studies have shown that Rap1 is able to regulate multiple signaling pathways, including MAPK (ERK,20,21,47,48 p38,22,23 JNK24-26 ) and PI3K/AKT27-30 pathways. Studies have also demonstrated that Rap1 is involved in LPS,49,50 BCR,30,51 and SDF-1 signaling.52-54 To elucidate the molecular basis of the impairment of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells, we examined the effect of Rap1b deficiency on LPS, BCR, and SDF-1 signaling. MZ B cells respond strongly, whereas FO B cells respond weakly to LPS stimulation.11,55 Thus, MZ B cells were sorted from the spleens derived from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice. After LPS stimulation, the activation of ERK, p38, JNK, and AKT was examined by direct Western blot analysis. The magnitude and kinetics of the activation of ERK, p38, JNK, and AKT were comparable in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells upon LPS stimulation (Figure 7A). In addition, mature FO B cells from the spleens derived from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stimulated with anti-IgM. Likewise, the magnitude and kinetics of the activation of ERK, p38, JNK, and AKT were comparable in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells upon BCR engagement (Figure 7B). Thus, Rap1b deficiency had no effect on LPS- and BCR-induced activation of ERK, p38, JNK, and AKT.

Normal activation of MAPKs and AKT by LPS, BCR, and SDF-1, and impaired activation of Pyk-2 by SDF-1 in Rap1b-deficient B cells. (A) LPS-induced activation of MAPK family members ERK, p38, and JNK and AKT in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells. Sorted MZ B cells from the spleen of wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stimulated with LPS for the indicated times. The cells were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-p38, anti–phospho-JNK, anti–phospho-AKT, or anti-Actin antibodies. The figure shown is representative of 2 independent analyses. (B) BCR-induced activation of MAPK family members ERK, p38, and JNK and AKT in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells. Sorted FO B cells from the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody for the indicated times. The cells were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-p38, anti–phospho-JNK, anti–phospho-AKT, or anti-Actin antibodies. The figure shown is representative of 2 independent analyses. (C) SDF-1–induced activation of ERK, AKT, and Pyk-2 in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells. Purified B cells from the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stimulated with SDF-1 for the indicated times. The cells were lysed and cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-AKT, anti–phospho-Pyk-2, anti–Pyk-2, or anti-Actin antibodies. The figure shown is representative of 5 independent analyses.

Normal activation of MAPKs and AKT by LPS, BCR, and SDF-1, and impaired activation of Pyk-2 by SDF-1 in Rap1b-deficient B cells. (A) LPS-induced activation of MAPK family members ERK, p38, and JNK and AKT in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells. Sorted MZ B cells from the spleen of wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stimulated with LPS for the indicated times. The cells were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-p38, anti–phospho-JNK, anti–phospho-AKT, or anti-Actin antibodies. The figure shown is representative of 2 independent analyses. (B) BCR-induced activation of MAPK family members ERK, p38, and JNK and AKT in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells. Sorted FO B cells from the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody for the indicated times. The cells were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-p38, anti–phospho-JNK, anti–phospho-AKT, or anti-Actin antibodies. The figure shown is representative of 2 independent analyses. (C) SDF-1–induced activation of ERK, AKT, and Pyk-2 in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient B cells. Purified B cells from the spleen of wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were stimulated with SDF-1 for the indicated times. The cells were lysed and cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-AKT, anti–phospho-Pyk-2, anti–Pyk-2, or anti-Actin antibodies. The figure shown is representative of 5 independent analyses.

In addition to MAPK and AKT pathways, SDF-1 induces the activation of the tyrosine kinase Pyk-2.56 Pyk-2 plays an essential role in SDF-1–mediated migration of B cells.15 Thus, purified splenic B cells were sorted from the spleens derived from wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with SDF-1. The magnitude and kinetics of the activation of ERK and AKT were comparable in wild-type and Rap1b-deficient splenic B cells upon SDF-1 stimulation (Figure 7C). In contrast, SDF-1–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk-2, an indicator of its activation,57 was reduced in Rap1b-deficient relative to wild-type splenic B cells (Figure 7C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Rap1b deficiency has no effect on LPS-, BCR-, or SDF-1–induced activation of MAPKs and AKT, but clearly impaired SDF-1–mediated activation of Pyk-2. Impaired activation of Pyk-2 can be at least one of the mechanisms for reduced SDF-1–mediated B-cell migration.15

Discussion

Rap1a and Rap1b are 95% homologous to each other; however, studies of Rap1a-deficient and Rap1b-deficient mice demonstrate distinct roles of these 2 Rap1s in vivo.39,58,59 Deficiency of Rap1a impairs integrin-mediated T- and B-cell adhesion but has no obvious effect on the immune system.58 In contrast, lack of Rap1b specifically impairs the function of platelets and the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells.39,59 Although previous studies of the GAPs for Rap1 and the Rap1 effector molecule RAPL indicate that Rap1 might play an important role in B-cell adhesion, migration, and BCR repertoire,34-38 no direct evidence demonstrates a role of Rap1a or Rap1b in B cell biology. Our finding that B cells predominantly express Rap1b instead of Rap1a suggests a possible role for the Rap1b isoform in B cell biology. Rap1a deficiency has no consistently obvious effect on B-cell development and function.58 In contrast, here we have found that Rap1b is important for B-cell biology; its deficiency reduces MZ B population and impairs B-cell trafficking to lymph nodes.

Previous studies have shown that Rap1 is involved in the regulation of MAPK activation.20-26 Some evidence shows that Rap1 may interfere with ERK activation,20 but there are also data illustrating that Rap1 can directly activate the MEK/ERK pathway.21 Rap1 has been shown to induce MEK3/6-mediated p38 activation22,23 and may be involved in the activation of JNK.24-26 Moreover, Rap1 has been shown to regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway.27-30 Rap1 is also involved in signaling of multiple receptors, including those for LPS, antigen, and SDF-1.30,49-54 Nonetheless, our data demonstrate that Rap1b deficiency has no obvious effect on the activation of MAPKs and PI3K/AKT by LPS or BCR in B cells. In agreement with this, LPS- and BCR-mediated B-cell survival and proliferation are normal in Rap1b-deficient B cells. Rap1b is predominantly expressed, whereas Rap1a is marginally expressed, in B cells. Although it is very likely that Rap1 may not participate in the activation of MAPKs and PI3K/AKT by LPS or BCR in B cells, the possibility that the low levels of Rap1a may compensate Rap1b deficiency in the activation of these pathways cannot be excluded. A double-knockout of Rap1a and Rap1b in B cells is required to address the issue.

Although Rap1b-deficient B cells have normal SDF-1–induced activation of ERK and AKT, Rap1b deficiency clearly impairs SDF-1–induced activation of Pyk-2. Pyk-2 plays an essential role in chemokine-induced B-cell migration, because B cells from Pyk-2-deficient mice have defective SDF-1–mediated chemotactic response.15 Consistent with our finding, previous studies have shown that overexpression of Rap-specific GTPase-activation protein (RapGAPII) blocks Rap1 activation, resulting in an impaired chemokine-induced activation of Pyk-2 in B-cell lines.34,38 Our results provide direct evidence that Rap1b is important for SDF-1–mediated activation of Pyk-2.

The requirements for the development of the 3 subsets of mature B cells, FO, B1 and MZ, seem to be different. It has been suggested that strong, intermediate and weak BCR signals favor B1, FO, and MZ B-cell development, respectively.60 Complete absence of BCR signals results in the loss of FO, B1, and MZ B cells.61 Severely weakened BCR signals (for example, as a result of the deficiency of Btk or PLCγ262,63 ) lead to loss of FO and B1 but not MZ B cells. Slightly weakened BCR signals (for example, as a result of deficiency of protein kinase Cβ) cause loss of B1 but not FO and MZ B cells.64 Other signals, including those derived from chemokines, also participate in the development of mature B cells.13 Defective B-cell chemotactic response or retention at the right site can also affect the development of mature B cells.13,14 Pyk-2 plays an important role in signaling of chemokines, including SDF-1, and the impairment of chemokine-mediated B-cell migration by lack of Pyk-2 may partly contribute to the loss of MZ B cells in Pyk-2–deficient mice.15 Lsc, a Rho GTP exchange factor, is involved in chemokine signaling, and mice lacking Lsc also suffer severe impairment of MZ B-cell development.16 Dock2, an activator of Rac, is indispensable for B-cell chemotaxis, and its deficiency impairs MZ B-cell development.17 Rap1b deficiency consistently impairs SDF-1–induced activation of Pyk-2, resulting in a defective SDF-1–mediated chemotaxis and a severe reduction of MZ B cells. Moreover, deficiency of RapL, the Rap1 effector molecule, severely impairs B-cell chemotaxis and development of MZ B cells.37 Thus, a signaling cascade that involves activation of Dock2, Lsc, Rap1b, RapL, and Pyk-2 seems to be essential for SDF-1–mediated B-cell migration and subsequent MZ B-cell development.

It is noteworthy that the effect of Rap1b deficiency on MZ B cells is similar to but also different from that of Pyk-2 deficiency.15 Lack of Rap1b or Pyk-2 impairs MZ B-cell migration mediated by chemokines, including SDF-1, BLC, and SLC. The MZ B-cell defects in Rap1b-deficient or Pyk-2-deficient mice are B-cell autonomous. MZ B cells are major players involved in initiating a rapid and effective humoral immune response to TI antigens, whereas FO B cells participate later in the TD antibody responses.65,66 The response of Pyk-2–deficient mice to TI antigens is impaired, and that to TD antigens is largely normal. Likewise, Rap1b-deficient mice have a slightly impaired TI immune response, but normal TD immune response. However, Pyk-2–deficient mice have almost no MZ B cells, whereas Rap1b-deficient mice still have a significant number of residual MZ B cells. The more severe effect on MZ B cells of Pyk-2 deficiency, compared with that of Rap1b deficiency, could be due to the partial impairment of Pyk-2 activation caused by lack of upstream Rap1b. In addition, Pyk-2 could be involved in more signaling pathways than Rap1b.

SDF-1 plays a critical role in B-cell chemotaxis.13 Deficiency of SDF-1 or its receptor CXCR4 blocks B lymphopoiesis by preventing colonization of hematopoietic progenitors in BM but has no obvious effect on B-cell homing to the peripheral lymphoid organs.67-71 SDF-1 is known to be only one of the several chemokines that regulate B-cell homing.72 Thus, lack of prominent effect of SDF-1 or CXCR4 deficiency on MZ B cells is probably due to functional compensation of other chemokines. On the other hand, Rap1b or Pyk-2 deficiency impairs the functions of multiple chemokines, leading to the loss of MZ B cells.15

It is noteworthy that distortion of the splenic microarchitecture (for example by the lack of the nuclear factor-κB family member RelB in nonlymphoid cells) is also able to impair MZ B-cell development.46 However, Rap1b-deficient BM cells, but not wild-type BM cells, have an impaired ability to develop into MZ B cells in JAK3−/− recipient mice. Thus, it is unlikely that Rap1b deficiency could indirectly affect MZ B cells by distortion of the splenic microenvironment; rather, the failure of Rap1b-deficient mice to generate MZ B cells seems to result from an intrinsic B-cell defect. Nonetheless, it also is possible that Rap1b could participate in the signaling of an as yet undefined receptor to contribute to MZ B-cell maturation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Jillian Dargatz for help in maintaining the Rap1b mouse colony and Ms Tina Johnson for critically reading the manuscript.

The study was supported in part by an AHA Scientist Development Grant 0235127N (to M.C.W.), by National Institutes of Health grants (P01-HL45100 to G.C.W. and R01-HL073284 to D.W.), and by a Scholar Award from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (to D.W.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. M.Y. performed some experiments and analyzed data. A.P. performed some experiments, analyzed data, and performed statistical analysis. R.W. analyzed data and critically reviewed the manuscript. M.C.W. contributed to scientific design, contributed vital new mutant mice and critically reviewed the manuscript. G.C.W. contributed vital new mutant mice and critically reviewed the manuscript. D.W. designed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Demin Wang, Blood Research Institute, 8727 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: demin.wang@bcw.edu.

![Figure 4. Normal apoptosis and proliferation of B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Normal apoptosis in naive Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells. Splenocytes from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. The degree of TUNEL positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate TUNEL-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 3 independent analyses. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentages of TUNEL-positive MZ B cells from panel A (3 mice of each genotype). (C) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells in vivo. Wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were injected with BrdU every 12 hours for 4 days. Splenocytes from the mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Cells were then permeabilized, fixed, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU. The degree of BrdU positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate BrdU-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 2 mice per genotype. (D) Statistical analysis of the percentages of BrdU-positive MZ B cells from panel C (2 mice of each genotype). (E) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells in response to LPS in vitro. MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) and FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) B cells were sorted from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient splenic mature B cells in response to LPS, anti-IgM, or anti-IgM plus IL-4 in vitro. Splenic mature B cells were purified from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS, anti-IgM or anti-IgM plus IL-4 for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/9/10.1182_blood-2007-12-128140/4/m_zh80100819260004.jpeg?Expires=1766006819&Signature=Mb1CcOrnRce9ZKVsjiV8IN~CYWtUpUP0pG6USkYx2RtVn5V68TYApCZSmdufRcX0zdPaCo5ukYEJfOQL7X55XzEcQKKv4NisJ6sJVihUHn1nybqYvFXb66Us-Jtg5U1kRQ5r4hjU23o15HMMHX~he-l~ZHGXgdhJ5P3e79lBsnZunEdYIEJODhSqA8fE2gP2M4S2A1YS1o65MSVIRgvrHwTuktlFmjgtbO8E8pyJkYFZX5nT1laLGXe~gBffTTjAp8eFmdwexYny4SVJ~NLziwGQ3sqXJgN6r021EwkkFmVuM9v98gqGM8Lw9Go-xrKjAU508VTxZvXEEJQP11zmPA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Normal apoptosis and proliferation of B cells in Rap1b-deficient mice. (A) Normal apoptosis in naive Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells. Splenocytes from wild-type (+/+) and Rap1b-deficient (−/−) mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21, and anti-CD23 antibodies. The degree of TUNEL positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate TUNEL-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 3 independent analyses. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentages of TUNEL-positive MZ B cells from panel A (3 mice of each genotype). (C) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ B cells in vivo. Wild-type and Rap1b-deficient mice were injected with BrdU every 12 hours for 4 days. Splenocytes from the mice were stained with anti-IgM, anti-CD21 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Cells were then permeabilized, fixed, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU. The degree of BrdU positivity in the gated MZ B cells (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) was determined by FACS analysis. Percentages indicate BrdU-positive cells in the gated B-cell subpopulations. Data are representative of 2 mice per genotype. (D) Statistical analysis of the percentages of BrdU-positive MZ B cells from panel C (2 mice of each genotype). (E) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient MZ and FO B cells in response to LPS in vitro. MZ (CD23−CD21hiIgMhi) and FO (CD23+CD21intIgMlo) B cells were sorted from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Normal proliferation of Rap1b-deficient splenic mature B cells in response to LPS, anti-IgM, or anti-IgM plus IL-4 in vitro. Splenic mature B cells were purified from the splenocytes of wild-type or Rap1b-deficient mice and then stimulated with LPS, anti-IgM or anti-IgM plus IL-4 for 48 hours. Proliferative responses were determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/9/10.1182_blood-2007-12-128140/4/m_zh80100819260004.jpeg?Expires=1766067290&Signature=4qy5nwdq66SMCoBaf0XOPrr9~McxojSSb4~fY8eYZi0jNPhNNKIbnFrqHcq43rcDb7SWgTj8x~jDE0cGEoculoy6SS4XC1P5mq2qaKiQ~IbxEOV~fi2m05LNPOEXGstVxgEtsYM9TnAccB7hN9bbp7DcNcJw3HrP1b7AHb6hffom3KIBxeYqFdGJA6Wns4Qz4x3EtPqV1MTrEsxruG3qoS9FW1bVY8UyxlG8MKkX50VUZDPkSFlwgRzEWVFHMxUco~VPjnAk5-9s842INmn70ng3xo7QUkNuTAzaKr-az7tREcI~UNEiY5~Fvq7RTSWyhACfq20R9z~zP2~oagXoHQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)