Abstract

Anticoagulation management of patients with recent heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery is a serious challenge, and especially difficult in patients requiring urgent heart transplantation. As nonheparin anticoagulants during CPB bear a high risk of major bleeding, these patients are at risk of being taken off the transplant list. Short-term use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) for CPB, with restriction of UFH to the surgery itself, is safe and effective in patients with a history of HIT who test negative for antiplatelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin antibodies. We present evidence that it is safe to expand the concept of UFH reexposure to patients with subacute HIT (ie, those patients with recent HIT in whom the platelet count has recovered but in whom anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies remain detectable) requiring heart transplantation, if they test negative by a sensitive functional assay using washed platelets. This can be lifesaving in patients with end-stage heart failure.

Introduction

Management of patients with recent heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery is a serious challenge for the consulting hematologist. In particular, the choice of adequate anticoagulation management during CPB is problematic. The situation is especially difficult in patients requiring heart transplantation, as the timing of surgery usually cannot be planned in advance, whereas the use of alternative anticoagulants during CPB requires special monitoring and preparation1,2 and bears a significantly enhanced bleeding risk.3 A major conceptual breakthrough was the recognition that use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) for CPB in patients with a history of HIT is safe and effective, provided that circulating anti-PF4/heparin antibodies are no longer detectable.4 This approach is now a Grade 1 recommendation for patients with a history of HIT requiring CPB.2 However, optimal management of patients with subacute HIT in whom platelet counts have normalized, but in whom anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies are still detectable by enzyme immunoassay (EIA), remains uncertain.

We report evidence that in these patients, UFH is an option for anticoagulation during CPB if a sensitive functional assay using washed platelets, such as the heparin-induced platelet activation (HIPA) test,5 is negative.

Methods

Anti-PF4/heparin antibodies were determined by EIA separately for IgG, IgA, and IgM6 ; heparin-dependent platelet-activating antibodies were determined by HIPA.5 Heart transplantation was performed according to standard procedure using UFH adjusted by activated clotting time (ACT) and neutralized by protamine after CPB.

Results and discussion

Case 1

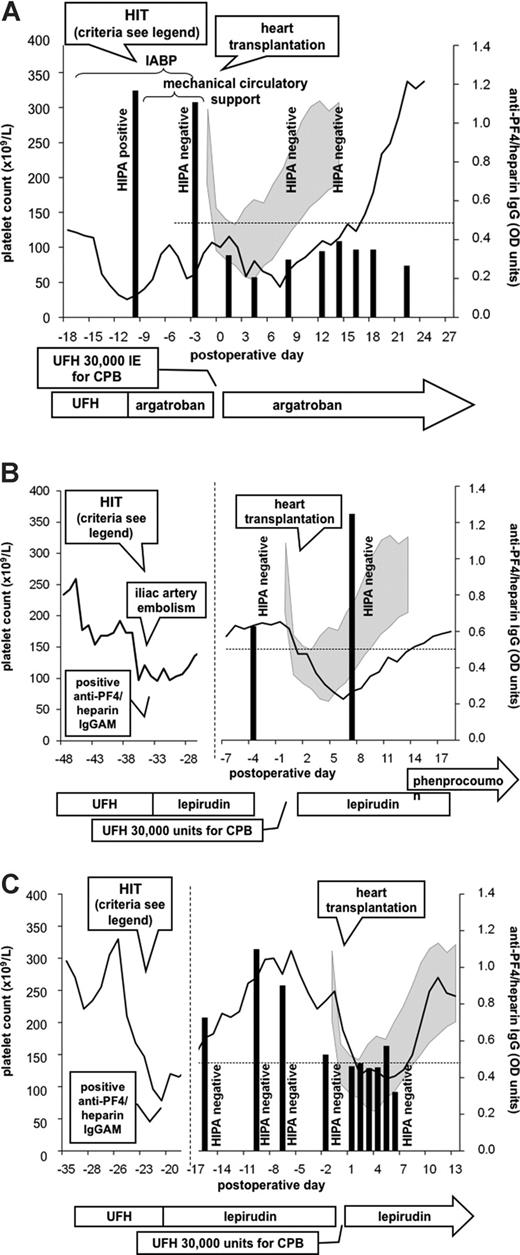

A 55-year-old male patient with severe dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and cardiogenic shock was scheduled for high urgency heart transplantation. At day 9 of UFH treatment, HIT developed (platelet count fall from 135 × 109/L to 28 × 109/L; anti-PF4/heparin IgG [optical density (OD) = 1.1] and positive HIPA; 4T score7 = 5). After switch of anticoagulation to argatroban (aPTT 50-60 seconds) platelet counts recovered rapidly. When a donor heart became available 1 week later, the patient still tested positive for anti-PF4/heparin IgG (OD = 1.1) but negative in the HIPA, and heart transplantation was performed using standard UFH anticoagulation for CPB. Postoperatively, major bleeding occurred (2100 mL in 12 hours) that stopped after surgical revision. Anticoagulation was continued with argatroban. Anti-PF4/heparin IgG declined (OD = 0.32 on postoperative day 1), remained negative (OD < 0.4 until postoperative day 13) as did the HIPA, and platelet counts normalized (Figure 1A). Multiorgan failure required prolonged intensive care treatment; however, no thrombotic events occurred, and the patient was discharged 113 days after surgery.

Three patients scheduled for heart transplantation with end-stage heart failure complicated by subacute heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). In all 3 patients, heart transplantation was successfully performed using short-term unfractionated heparin (UFH) during transplantation despite a positive anti-PF4/heparin IgG by enzyme-immunoassay (EIA). Results of the EIA test are represented by black vertical bars; results of the heparin-induced platelet-activating (HIPA) test are given as text; platelet count courses are represented by lines. The gray shaded area represents standard deviation (plus or minus) of mean platelet counts of 10 consecutive non-HIT patients after heart transplantation. The clinical course and laboratory test results (obtained from another hospital in patients 2 and 3) are given at the left hand side of the figure. Criteria to diagnose HIT in patient 1 were platelet decrease greater than 50% after 9 days of heparin treatment, positive anti-PF4/heparin IgG, positive HIPA, and rapid increase of platelet count after switching from heparin to argatroban. Criteria to diagnose HIT in patient 2 were platelet decrease greater than 50% after 7 days of heparin treatment, complicated by iliac artery embolism, positive anti-PF4/heparin IgGAM by a commercial EIA, and rapid increase of platelet count after switching from heparin to lepirudin. Criteria to diagnose HIT in patient 3 were platelet decrease greater than 50% after 7 days of heparin treatment, positive anti-PF4/heparin IgGAM by a commercial EIA, and rapid increase of platelet count after switching from heparin to lepirudin. CPB indicates cardiopulmonary bypass; IABP, intraaortic balloon pump; and OD, optical density.

Three patients scheduled for heart transplantation with end-stage heart failure complicated by subacute heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). In all 3 patients, heart transplantation was successfully performed using short-term unfractionated heparin (UFH) during transplantation despite a positive anti-PF4/heparin IgG by enzyme-immunoassay (EIA). Results of the EIA test are represented by black vertical bars; results of the heparin-induced platelet-activating (HIPA) test are given as text; platelet count courses are represented by lines. The gray shaded area represents standard deviation (plus or minus) of mean platelet counts of 10 consecutive non-HIT patients after heart transplantation. The clinical course and laboratory test results (obtained from another hospital in patients 2 and 3) are given at the left hand side of the figure. Criteria to diagnose HIT in patient 1 were platelet decrease greater than 50% after 9 days of heparin treatment, positive anti-PF4/heparin IgG, positive HIPA, and rapid increase of platelet count after switching from heparin to argatroban. Criteria to diagnose HIT in patient 2 were platelet decrease greater than 50% after 7 days of heparin treatment, complicated by iliac artery embolism, positive anti-PF4/heparin IgGAM by a commercial EIA, and rapid increase of platelet count after switching from heparin to lepirudin. Criteria to diagnose HIT in patient 3 were platelet decrease greater than 50% after 7 days of heparin treatment, positive anti-PF4/heparin IgGAM by a commercial EIA, and rapid increase of platelet count after switching from heparin to lepirudin. CPB indicates cardiopulmonary bypass; IABP, intraaortic balloon pump; and OD, optical density.

Case 2

A 55-year-old male patient with post–myocardial infarction congestive heart failure (left ventricular ejection fraction 25%) developed HIT at day 7 of UFH therapy (platelet count fall from 259 × 109/L to 97 × 109/L, iliac artery thrombosis; positive anti-PF4/heparin-EIA [HPIA; Diagnostica Stago, France], 4T score = 7). After switching anticoagulation to lepirudin (aPTT 50-60 seconds) platelet counts recovered. When cardiac function further deteriorated heart transplantation was scheduled. At that time the patient still tested positive for anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies by EIA (OD 0.627 OD; cutoff 0.500), but had a negative HIPA test. Three days later, a donor heart became available and heart transplantation was performed using standard UFH anticoagulation for CPB with no major bleeding (postoperative chest tube drainage 1200 mL in 48 hours). Lepirudin was restarted approximately 8 hours after surgery. Anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies increased at day 7 after transplantation (OD = 1.248), but the HIPA remained negative (Figure 1B). No thromboembolic complications occurred, and the patient was discharged 35 days after surgery.

Case 3

A 44-year-old male patient was scheduled for heart transplantation for severe DCM and therapeutic dose anticoagulation with phenprocoumon was switched to UFH (aPTT 50-60 seconds). One week later, HIT developed (platelet count fall from 330 × 109/L to 78 × 109/L; positive anti-PF4/heparin EIA [HPIA; Diagnostica], 4T score = 6). After switch to lepirudin (aPTT 50-60 seconds), platelet counts normalized. Subsequent testing for HIT antibodies within 2 weeks showed a decrease of anti-PF4/heparin IgG levels (OD from 1.099 to 0.526; cutoff 0.500) and a negative HIPA. When a donor heart became available, lepirudin was stopped 4 hours before surgery. Anticoagulation during CPB was performed using standard UFH protocol, with no major bleeding (chest tube drainage 600 mL in the first postoperative 48 hours), lepirudin was restarted (aPTT 50-60 seconds) 6 hours postoperatively (Figure 1C). The further course was complicated by prolonged cardiac shock and intensive care treatment. However, no thrombotic events occurred, and the patient was discharged 91 days after surgery.

Cessation of heparin and use of alternative nonheparin anticoagulation are basic therapeutic principles of HIT.2,8 Furthermore, heparin reexposure in patients with circulating platelet-activating anti-PF4/heparin antibodies should be avoided, as this can cause “rapid-onset” HIT complicated by thromboembolic events or anaphylactoid reactions.4,9,10

However, HIT antibodies unusually become undetectable within 3 months after an episode of HIT. Further, in patients with previous HIT in whom antibodies are no longer detectable, it takes at least 5 days for antibodies to recur after heparin reexposure.4 These observations, together with the significantly enhanced bleeding risk if alternative anticoagulants are used during CPB,3 has led to the strategy of short-term use of UFH for CPB surgery when the patient tests negative for HIT antibodies,11-13 with restriction of heparin to the surgery itself.

Recently, Schroder et al14 reported a retrospective case series of patients with a positive PF4/heparin EIA reexposed to heparin for heart transplantation without an increase of adverse events as compared with antibody negative patients. However, in the view of numerous reports showing acute onset HIT in patients with biologically relevant circulating antibodies15 this strategy may bear a substantial risk in the individual patient. Most hematologists would be very reluctant to recommend heparin reexposure if anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies are still present.

We now provide prospective data indicating that short-term use of UFH is feasible in patients with subacute HIT in whom anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies are still detectable by EIA, but who show a negative washed platelet activation assay. Washed platelet activating assays have a higher specificity for biologically active HIT antibodies and provide among all other HIT tests the best specificity for clinical HIT.16 Therefore, a negative functional assay suggests that residual biologically active antibodies are unlikely to be present.17,18 This strategy is feasible in countries where functional HIT tests are available from a network of trained laboratories, providing assays in a turnaround time and of sufficient quality that clinical decisions may be based on the test result. (Potential alternative approaches are given in Table 1.)

In 2 of the patients, no functional assay was performed at the time when acute HIT was diagnosed. However, the residually detectable anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies, together with the clinical presentation (Figure 1), were very suggestive of recent HIT when anticoagulant management during heart transplantation had to be decided. None of the 3 patients developed platelet-activating antibodies, and there was no evidence for HIT-related thrombotic events after reexposure to UFH. However, compared with non-HIT patients (illustrated as gray shaded area in the figure), platelet count recovery after heart transplantation seemed to be somewhat delayed. This might indicate that the persistent antibodies, although not causing thrombosis, may still impair platelet count recovery.

These 3 patients indicate that the concept of short-term use of UFH during CPB in patients with previous HIT might be expanded to patients with subacute HIT in whom anti-PF4/heparin IgG antibodies are still detectable by EIA, but who test negative by a sensitive platelet activation assay. This strategy increases the feasibility of heart transplantation in patients with end-stage heart failure.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.G. designed the study; A.H., S.S., S.H., and C.S. collected and analyzed data; S.S., K.S., and A.G. wrote the manuscript; and all authors revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Prof Dr Andreas Greinacher, Institut für Immunologie und Transfusionsmedizin, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt Universität, D-17475 Greifswald, Sauerbruchstrasse, Germany; e-mail: greinach@uni-greifswald.de.

References

Author notes

*S.S. and A.H. contributed equally to this study.