Abstract

Outcomes of unrelated donor cord blood transplantation in 191 hematologic malignancy children (median age, 7.7 years; median weight, 25.9 kg) enrolled between 1999 and 2003 were studied (median follow-up, 27.4 months) in a prospective phase 2 multicenter trial. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching at enrollment was 6/6 (n = 17), 5/6 (n = 58), 4/6 (n = 111), or 3/6 (n = 5) by low-resolution HLA-A, -B, and high-resolution (HR) DRB1. Retrospectively, 179 pairs were HLA typed by HR. The median precryopreservation total nucleated cell (TNC) dose was 5.1 × 107 TNC/kg (range, 1.5-23.7) with 3.9 × 107 TNC/kg (range, 0.8-22.8) infused. The median time to engraftment (absolute neutrophil count > 500/mm3 and platelets 50 000/μL) was 27 and 174 days. The cumulative incidence of neutrophil engraftment by day 42 was 79.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75.1%-85.2%); acute grades III/IV GVHD by day 100 was 19.5% (95% CI, 13.9%-25.5%); and chronic GVHD at 2 years was 20.8% (95% CI, 14.8%-27.7%). HR matching decreased the probability of severe acute GVHD. The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 19.9% (95% CI, 14.8%-25.7%). The probabilities of 6-month and 2-year survivals were 67.4% and 49.5%. Unrelated donor cord blood transplantation from partially HLA-mismatched units can cure many children with leukemias. The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00000603.

Introduction

Despite major advances in curing children with leukemias over the last 30 years, approximately 20% of patients relapse and are candidates for transplantation.1,2 Many of these patients will not be able to identify a matched related or unrelated bone marrow donor in a timely fashion.3 Partially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–mismatched banked unrelated donor cord blood units are readily available for the majority of these patients. Although results of unrelated donor cord blood transplantation (UCBT) in children with hematologic malignancies have been published from registry data,4-9 no prospective, multicenter study has been reported to date.

The Cord Blood Transplantation Study (COBLT) study was an National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored, phase 2, multicenter study designed to establish public cord blood banks using common standards and operating procedures10,11 and to determine through a multicenter clinical trial if banked unrelated donor umbilical cord blood could serve as an adequate hematopoietic stem cell source for adults12 and children with malignancies, immune deficiencies, inherited marrow failure, or inborn errors of metabolism.13,14 A list of the members of the COBLT Steering Committee appears in the Appendix (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online artcle). The largest stratum of the COBLT trial studied pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies. We now report the outcomes of UCBT in the pediatric patients enrolled in this stratum.

Methods

Study overview

The transplantation protocol for pediatric malignancies was approved at the Institutional Review Board of each of the 26 participating institutions. The first and last patients received transplantations in March 1999 and October 2003, respectively. All patients or their legal guardians were required to give written informed consent before enrollment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Eligible subjects were pediatric patients diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy that relapsed or were at very high risk of relapse on frontline therapy (remission induction failures, Ph+, hypodiploid). Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) with very high risk features were eligible in first complete remission (CR) along with all patients with ALL in second or subsequent CR (CR1 < 18 months, or ≥ CR3) or relapse. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) were eligible in any CR or relapse. Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) were eligible in chronic or accelerated phase. Patients with active central nervous system (CNS) disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seropositivity, Lansky performance scores less than 50%, age more than 18 years, primary myelofibrosis, suitable related (5/6 or 6/6 matched) donors were ineligible. Patients with prior allogeneic stem cell transplantation within 12 months, or autologous transplantation within 6 months, were excluded, as were individuals with uncontrolled infections. Patients had to have adequate organ function and no contraindication to total body irradiation therapy.14 Patients could not have an available matched related donor or an unrelated matched donor who could be harvested in a timely manner.

Donor characteristics

All patients received a transplantation of a single cord blood unit (CBU) that provided a minimum of 107 total nucleated cells (precryopreservation) per kilogram of recipient weight. The donor units were required to match the patient at a minimum of 4 of 6 HLA loci using low/intermediate resolution typing at HLA class I (A and B) and high resolution typing at DRB1 or at 3 of 6 loci if there was molecular (high resolution) matching at 1 allele of each locus (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-DRB1). Matching was not required at HLA-C or DQB1 but was evaluated at some centers. Units were obtained from COBLT, the New York Blood Center, or National Marrow Donor program US cord blood banks. The HLA matching between the CBU and the patient, as determined by low/intermediate molecular typing for class I (HLA-A and HLA-B) alleles, and high resolution molecular typing for HLA-DRB1 alleles at the time of enrollment, was referred to as “original HLA typing.”

Retrospective HLA typing

Retrospective typing was performed at increasing levels of resolution, including allele level typing, until a mismatch was discovered on 179 donor/recipient pairs, at 2 reference laboratories (Baxter-Lowe laboratory at University of California San Francisco and the Naval Medical Research Institute laboratory) for HLA-A and HLA-B. High resolution typing for HLA-DRB1 was available on these 179 pairs from the pretransplantation analysis. New HLA data are referred to as “final HLA typing” and used as a separate variable for outcomes analysis.

Preparative regimen, graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, and supportive care

The conditioning regimen consisted of 1350 cGy of total body irradiation given in 9 twice-daily fractions (150 cGy) on days −8 through −4. Cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg was administered on days −3 and −2. Methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg was given before each dose of antithymocyte globulin (equine) of 15 mg/kg twice daily on days −3 through −1. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis included methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg twice daily on days 1 through 4, 1 mg/kg twice daily beginning day 5, and continuing until the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) reached 500/mm3, and then tapered. Cyclosporine was permitted to begin between days −3 and −1 and was dosed to achieve trough levels measured by polyclonal immunoassay of more than or equal to 200 ng/mL when administered by bolus dosing or 400 ng/mL when administered by continuous infusion. Cyclosporine prophylaxis was continued for at least 6 months and then tapered per institutional protocol. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was administered to all patients beginning on day 0 and continued until engraftment. All patients were supported with empiric antibiotic therapies for fever; antifungal, antiviral, and anti-Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis and intravenous immunoglobulin according to institutional practices. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) was monitored by weekly antigen or polymerase chain reaction screening and preemptive therapy was initiated with ganciclovir and CMV immune globulin if rising CMV in the blood or signs of clinical disease were observed. Acute and chronic GVHD was scored according to the standard criteria.15,16

Transplantation procedure

CBUs were thawed, washed, and processed according to the standard procedures provided by the study.17 All centers were trained in and used the same thawing procedure to prepare the CBU for infusion. The total number of nucleated cells, clonal hematopoietic progenitor cells, and CD3+ and CD34+ cells were counted, ABO and Rh typing was performed, cell viability was assessed, and bacterial and fungal cultures obtained both at the time of banking and thawing. There was no special treatment of the cord blood if ABO and/or RH incompatibility was present because overall red blood cell content was small and isohemagglutinins are not present in cord blood. After processing, the CBU was brought to the bedside and infused through a central venous line over 10 to 30 minutes.

Study endpoints and statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of the study was survival at 180 days after transplantation. The secondary endpoints included engraftment (neutrophil and platelet), acute and chronic GVHD, disease-free survival, long-term survival, relapse, and regimen-related toxicities. The impact of HLA match, cell dose, race or ethnicity, disease status, age, performance status, risk status, and patient CMV seropositivity were assessed. Risk status is defined in Table 1. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days of achieving an ANC of 500/μL with more than 90% donor cell chimerism. Platelet engraftment was defined as achieving a platelet count of 50 000/μL without transfusion support for 7 days. Primary graft failure was defined as failure to reach an ANC of 500/μL by day 42. Secondary graft failure was defined as either severe persistent neutropenia unresponsive to growth factor therapy or loss of donor chimerism after initial engraftment. Relapse was defined as more than 25% blasts in the blood or bone marrow or more than 5% blasts in the bone marrow with reappearance of the original cytogenetic abnormality associated with patient's malignancy or more than 5% blasts in the bone marrow on multiple occasions or any extramedullary relapse. Infection and toxicity were graded as outlined (https://web.emmes.com/study/cord/protocol.htm). Infections were graded according to the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry grading system operative at the start of the protocol in 1999.

Survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.18 Testing for differences in survival between groups in the univariate analysis used the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence curves were used for engraftment and GVHD endpoints with death as a competing risk.19 The Cox proportional hazards model with backward elimination was used for multivariate testing of covariates on the major endpoints. No imputation was used for missing data. All analyses were performed by statisticians at the Data Coordinating Center using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient enrollment

A total of 193 children (age ≤ 18 years) were enrolled from 22 centers; 2 died before transplantation. All patients were followed for a minimum of 6 months with a median follow-up of 27.4 months (range, 8.8-63.6 months).

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients are shown in Table 2. The majority of patients had either ALL (n = 109, 57%; 17, first CR; 65, second CR; 20, third CR; 6, relapse; 1, primary induction failure) or AML (n = 51, 27%; 13, first CR; 21, second CR; 6, primary induction failure; and 11, relapse). The remaining patients had myelodysplastic syndrome (8%, 2 with Kostmann), lymphoblastic lymphoma (3%), CML (4%), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (0.5%), and biphenotypic leukemia (1%). Most patients (77%) were high risk as defined in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 7.7 years (range, 0.9-17.9 years), median weight was 25.9 kg (range, 7.5-118.4 kg), 40% were nonwhite, 61% were male, and 51% were seropositive for CMV. The Lansky performance status was more than 80 for 85% of patients. No patient had a previous autologous transplantation, whereas 1 patient had relapsed after a previous allogeneic transplantation.

Donor characteristics and patient/donor matching

These characteristics are summarized in Table 3. COBLT banks supplied donor units for 61% of transplantations. The median total nucleated cell (TNC), CD34+, and CD3 doses in the cryopreserved grafts were 5.1 × 107 cells/kg (range, 1.5-23.7), 1.9 × 105/kg (range, 0.0-25.3), and 7.9 × 106/kg (range, 0.1-35.6), respectively. Sixty-eight percent of the donor/recipient pairs were ABO-matched, whereas 88% were Rh-matched (Table 3). Recipients and donors were matched for ethnicity in 61% and matched for gender in 50%. Total HLA matches are summarized in Table 4.

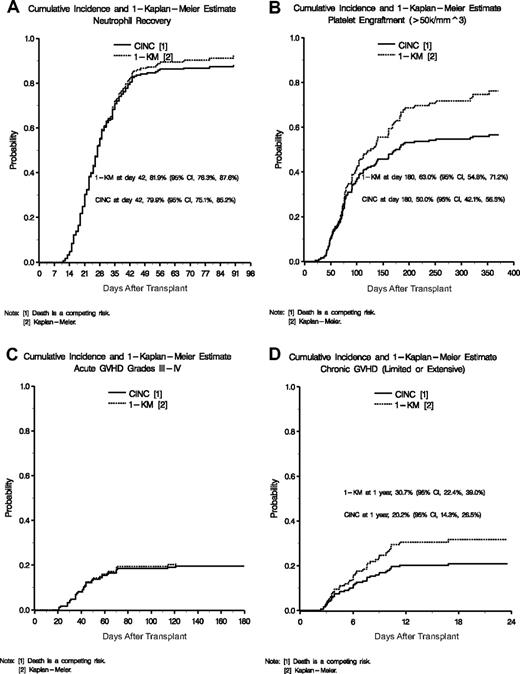

Neutrophil recovery

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery (ANC ≥ 500/mm3) by day 42 was 79.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 75.1%-85.2%) as shown in Figure 1A. An additional 14 patients recovered neutrophils between days 43 and 90. At 6 and 12 months, 86.9% of patients had sustained neutrophil engraftment. The median time to neutrophil recovery was 27 days (range, 11-90 days). Primary and secondary graft failure occurred in 21 and 2 patients, respectively.

Cumulative incidence of engraftment and GVHD. (A) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of neutrophil recovery. (B) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of platelet engraftment of 50 000. (C) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of acute GVHD grades III and IV. (D) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of chronic GVHD.

Cumulative incidence of engraftment and GVHD. (A) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of neutrophil recovery. (B) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of platelet engraftment of 50 000. (C) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of acute GVHD grades III and IV. (D) Cumulative incidences and 1-KM probability of chronic GVHD.

In univariate analysis, lower recipient weight (P = .02), higher original HLA match (P = .03), increasing TNC (P = .03), and CD34+ dose (P = .01) positively impacted neutrophil recovery. In a multivariate Cox model, both original HLA match (P = .04) and TNC dose were independently significant (P = .04; Table 5).

Platelet recovery

Cumulative incidence (CINC) and 1-Kaplan-Meier (1-KM) estimates of platelet engraftment (≥ 50 000/mm3) are displayed in Figure 1B. By day 180, the CINC for platelet engraftment was 50.0% (95% CI, 42.1%-56.5%) and the Kaplan-Meier estimate of platelet engraftment was 63.0% (95% CI, 54.8%-71.2%). At 1 year after transplantation, 87% of surviving patients had achieved a platelet count of more than 50 000/μL. The median duration to platelet engraftment was 174 days (range, 21-353 days). In univariate analysis, lower recipient age (P = .02) and weight (P = .02), white recipient race (P = .07), higher TNC (P = .01), and higher CD34+ cell dose (P = .03) favorably impacted time to platelet engraftment. In multivariate analysis, only higher TNC (> 5.1 × 107/kg; P = .03) was significant (Table 5).

GVHD

Acute GVHD (aGVHD) was graded by center and then reviewed retrospectively by an independent panel.15 The CINC of grades II to IV aGVHD was 41.9% (95% CI, 34.4%-48.7%) with death as a competing risk. Thirty-eight patients (CINC 19.5%; 95% CI, 13.9%-25.5%) had grades III or IV aGVHD (Figure 1C). In univariate analysis, the factors affecting aGVHD were original HLA match and gender. In multivariate analysis, original HLA match of 5 of 6 or 6 of 6 versus 4 of 6 had a hazard ratio of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.04-2.63; Table 5). High-resolution HLA analysis revealed that the probabilities of grades II to IV (P = .02) and grades III and IV (P = .02) aGVHD were significantly higher if the pairs were less than 5 of 6 matched. In addition, female patients had a significantly higher aGVHD. Other variables considered were infused TNC, CD3+, CD34+, recipient/donor sex, and recipient/donor ethnicity, but these were not significant.

Infection, hospitalization, and toxicity

Maximum toxicity in any organ system by day 42 was 23% grade 0 or 1, 49% grade 2, 24% grade 3, and 5% grade 4 using the Bearman scale.20 Seizures occurred in 34 patients, 20 between days 28 and 42. At least one severe life-threatening or fatal infection was reported in 166 patients within the first 6 months after transplantation. Bacterial infections were reported in 77% of patients, fungal infections in 33%, and viral infections in 61%. Two or more infections were experienced by 77% of patients. Of the 762 infectious episodes, 368 (48%) were attributed to bacteria, 258 (34%) to viruses, and 84 (11%) to fungi.

Relapse

The CINC of relapse at 2 years after transplantation was 19.9% (95% CI, 14.8%-25.7%; Figure 2A). Univariate analyses showed female gender (P < .01), ABO mismatch (P = .02), smaller TNC (P = .04), and CMV seropositive patient (P < .01) as significant predictors of relapse. In the multivariate analysis, patients with pretransplantation CMV seropositivity (P < .01), mismatched donor/recipient ABO (P = .03), and female recipient gender (P = .01) were at a significantly increased risk of relapse (Table 5). In patients with ALL or AML, disease status at transplantation was also predictive of relapse, and patients in first or second CR were significantly better off than those in third CR or relapse (Figures 2B and 3C,D).

Cumulative incidence of relapse. (A) Overall cumulative incidence and 1-M probability of relapse. (B) Cumulative incidence and 1-KM probability of relapse by stage of disease (first and second CR vs other).

Cumulative incidence of relapse. (A) Overall cumulative incidence and 1-M probability of relapse. (B) Cumulative incidence and 1-KM probability of relapse by stage of disease (first and second CR vs other).

Survival for patients with pediatric malignancies. (A) Overall survival. (B) Survival by recipient CMV pretransplantation serostatus. (C,D) Survival by disease status for patients with AML and ALL. (E,F) Survival by original and final HLA match.

Survival for patients with pediatric malignancies. (A) Overall survival. (B) Survival by recipient CMV pretransplantation serostatus. (C,D) Survival by disease status for patients with AML and ALL. (E,F) Survival by original and final HLA match.

Survival

Survival analysis is based on 191 patients who underwent the transplantation procedure. Survival was measured from the date of transplantation to date of death and was censored for survivors at the date of the last follow-up. Overall survival was 67.4% (95% CI, 60.7%-74.1%) at day 180, 57.3% (95% CI, 50.2%-64.3%) at 1 year, and 49.5% (95% CI, 42.3%-57.0%) at 2 years (Figure 3A). In univariate analysis, age, weight, gender, donor gender, donor/recipient gender combination, ethnicity, donor/recipient ethnicity combination, primary disease, precryo CD34+ dose, precryo CD3+ dose, precryo TNC dose, original HLA match, retrospective HLA match, performance status, risk, CMV, and ABO matching were evaluated. Sex, ethnicity (white), CMV pretransplantation (negative; Figure 3B), Lansky performance status (> 80%), original HLA match (6 of 6), final HLA match (6 of 6), ABO match (matched), and cell dose (> 2.5 × 107/kg) were favorable. In multivariate analysis, CMV (P < .01), ABO match (donor to recipient; P = .02), recipient gender (P < .01), and TNC (P = .04) were the only variables that remained significant for survival (Table 5).

Causes of death

Ninety-five of the 193 enrolled patients have died, and 93 of 191 patients who received a transplant have died. Sixteen patients died from graft failure, 25 from GVHD (18 acute and 7 chronic), 9 from infections, 37 from relapse, 4 from organ failure, 1 from pulmonary hemorrhage, and 1 from Epstein-Barr virus posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease. Infection was the secondary cause of death in 29 patients. There were 23 graft failures (21 primary and 2 secondary) of which 19 died (12 of graft failure, 4 from aGVHD + graft failure, and 3 of relapses before day 42). The cumulative incidence of regimen related mortality at 100 days was 17.0% (95% CI, 11.7%-22.8%). The probability of nonrelapse mortality at 6 months was 25.8% (95% CI, 18.6%-31.9%).

HLA matching

By original HLA typing, the majority of recipient/donor pairs were mismatched in both the GVHD and rejection directions at either one (30%) or 2 (58%) loci (Table 4). Only 9% of the pairs were 6-of-6 matched. Overall, HLA matching was demoted in 32% of recipient/donor pairs comparing original to final HLA match. Of 111 patients who were originally a 4-of-6 match, 8 were determined to be a 2-of-6 match and 30 to be a 3-of-6 match. Similarly, of the 58 patients originally considered to be a 5-of-6 match, 11, 2, and 1 were determined to be 4-of-6, 3-of-6, and 2-of-6, respectively, after high -resolution typing. Of 17 patients originally a 6-of-6 match, 2 were found to be otherwise (5-of-6 and 3-of-6, respectively) by high-resolution typing.

Discussion

We describe the results of the first prospective, multicenter, national trial of UCBT in 193 pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies. The study was undertaken to examine the outcomes of these transplantations and determine the usefulness of unrelated banked CBUs in expanding the donor pool for children with leukemia in need of transplantation but lacking adult bone marrow donors. To answer this question, only the patients who did not have a matched related or unrelated adult donor who was available for transplantation in a timely manner were enrolled in the study. The majority of patients (91%) received partially HLA-mismatched grafts and 40% represented ethnic minorities. All patients received a common conditioning regimen, GVHD prophylaxis, and similar supportive care. The majority of the children had high-risk disease (77%) and a good performance status score (84.8%). This study on the outcome of UCBT in this well-defined cohort provides very useful information. The overall survival in our patient population at 6 months and 1 year was 67.4% and 57.3%, respectively. These results are compared favorably with those published from registry data.7,21 The CINC of neutrophil recovery with donor cells by day 42 was 79.9%. Grade III or IV acute and overall chronic GVHD occurred in 19.5% and 20.2% of patients, respectively. Leukemic relapse occurred in 18.6% of patients with very few relapses after the first posttransplantation year. The most common primary causes of death were relapse (40%), GVHD (27%) with or without infection, and graft failure (17%).

Higher TNC dose (> 5.1 × 107/kg vs ≤ 5.1 × 107/kg) significantly improved the engraftment of neutrophils (P = .03) as well as the platelets (P = .03). The median cell dose of units selected and infused for transplantation in this pediatric patient cohort (selected precryopreservation count 5.1 × 107, infused 3.9 × 107) was larger than those previously reported in registry series.21 Patients receiving grafts selected to deliver a cell dose of less than or equal to 2.5 × 107 cells/kg had lower and slower engraftment than patients above this threshold (P = .04). In addition, patients receiving grafts containing precryopreserved TNC of less than or equal to 2.5 × 107cells/kg had significantly lower overall survival (P = .04). On the basis of these findings, we recommend that UCB grafts selected for pediatric patients receiving myeloablative transplantations for hematologic malignancies contain greater than 2.5 × 107 cells/kg based on the precryopreservation total nucleated cell count.

We examined the significance of retrospective high resolution HLA matching between donor and recipient. Original matching was based on low/intermediate resolution HLA class I (A and B) typing and high resolution DRB1 typing. When typed at high resolution for all 6 alleles, approximately one-third of the pairs were found to be more disparate. On multivariate analysis, higher original HLA match (≥ 5 of 6 vs ≤ 4 of 6) improved the engraftment of neutrophils (P = .04) but had no impact on the engraftment of platelets. Again, on multivariate analysis, the level of HLA matching at original typing had no impact on the occurrence of moderate/severe (grade II-IV) or severe (grade III-IV) acute GVHD. However, high resolution retrospective typing revealed that the probability of developing severe (grade III-IV) was significantly higher (P = .02) if the donor/recipient pair were matched for fewer than 5 of 6 alleles. In this patient cohort, the impact of original HLA match and final HLA match on graft failure and relapse did not reach statistical significance, possibly because of the small number of events. The impact of original and retrospective HLA matching on overall survival was also examined (Figure 3E,F). When original typing was considered, there was no difference in survival for patients receiving 5 of 6 or 4 of 6 matched grafts. There was, however, a trend for a survival advantage for the small number of patients (n = 17) receiving 6 of 6 matched grafts (P = .07). Conversely, the small number of patients transplanted with 3 of 6 matched grafts (n = 5) trended toward poorer survivals (P = .08). By retrospective, high resolution, HLA matching, there appeared to be a trend toward a survival advantage for patients receiving 6 of 6 matched grafts (n = 16, P = .12), although there was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between patients receiving 4 of 6 or 5 of 6 matched grafts. However, the small numbers of patients in this study may have decreased the statistical power of this analysis. On the basis of current data, we recommend selecting UCB units that are at least 4 of 6 by low/intermediate resolution typing at HLA class I (-A and -B) and high resolution typing at DRB1.

On multivariate analysis, the incidence of aGVHD was favorably influenced by matching for HLA and male gender. The incidence of cGVHD was significantly higher in female patients and younger age of the patient. Male gender, ABO matching, and negative pretransplantation recipient CMV serostatus were all protective against relapse. Overall survival was favorably impacted by pretransplantation CMV seronegativity of the recipient, recipient male gender, donor/recipient ABO matching (matched), HLA match (5 or 6 of 6), and TNC (higher TNC). Patients with ALL in CR1/CR2 fared significantly better than those in subsequent CR/relapse. In a recently reported correlative sub-study, patients capable of mounting T-cell proliferative responses to herpes viruses had a lower probability of relapse and higher overall survival.22 It is important to note that the overall survival in the minority patients was similar to that seen in white patients (P = .13).

It is interesting that many outcome measures showed advantage for a male recipient. On multivariate analysis, boys had lower incidence of grade 2-IV acute GVHD (hazard ratio = 1.78; P = .01), lower relapse rates (hazard ratio = 2.34; P = .01), and better survival (hazard ratio = 1.74; P < .01). These observations about gender differences may be clinically important. It is possible that the gender differences in the biology of leukemia may be contributing to these observations. However, we have seen higher survival in boys with inherited metabolic disorders undergoing UCBT.23 One might speculate that disparities of the H-Y minor histocompatibility antigens or differences in the degree of cytotoxicity may be contributing to these findings. These hypotheses should be tested in a much larger series of patients to be accepted as valid.

Engraftment did not occur in 12% of the patients enrolled in this study although the median cell dose was adequate. Other factors delaying or preventing engraftment included viral infections, persistent leukemic relapse, and inadequate host immunosuppression. Novel approaches to increasing engraftment include the use of 2 cord blood units for a single transplantation,24 which appears in pilot studies to increase the incidence of engraftment to 95% in adults. Augmentation of immunosuppression with pretransplantation fludarabine may also facilitate engraftment of these lower cell dose grafts.

In another strata of the COBLT study, children (n = 32) with infant leukemia who received nonlimiting cell doses of TNC/kg, CD3+ cells/kg, and CD34+ cells/kg, we noted similar estimates of neutrophil recovery and grade III-IV acute GVHD at day 100 and chronic GVHD.14 Notably, in that cohort, higher-level HLA match showed improved survival with the difference being statistically significant when considering the final high resolution HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1 match. Conversely, the cohort of children with metabolic diseases (n = 69) also received comparable cell doses to those with infant leukemia; HLA did not influence engraftment, GVHD, or survival.25 In the present study, HLA matching by low- or high-resolution criteria did not show conclusive impact on survival. These observations in different COBLT strata may reflect limited power of the data because of small sample sizes. High resolution HLA matching did decrease the risk of GVHD, and it is possible that the overall survival may remain unchanged because of the competing contributions of GVHD and graft-versus-leukemia effects. Further analysis in larger series will hopefully provide more conclusive observations about the impact of HLA matching and cell doses on the outcomes of UCBT.

More than 50% of the patients requiring hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are unable to find a suitable adult stem cell donor in a timely fashion, making donor availability a major obstacle to effective antileukemic therapy. Banked umbilical cord blood is prospectively HLA typed, screened for infections and other risk factors, and is readily available for use in patients who cannot identify a matched related or unrelated donor. The results using banked unrelated donor umbilical cord blood to treat children with hematologic malignancies presented in this study are similar to those reported using related and unrelated donor bone marrow in children with leukemia.7,25 Furthermore, as shown with bone marrow donors, transplantation in earlier stages of disease results in higher overall survival and leukemic cure. Thus, children who have high risk leukemia or have relapsed after standard therapy who do not have matched related or unrelated adult donors should be immediately referred and evaluated for unrelated donor cord blood transplantation before their disease status worsens, decreasing their chances for successful outcomes with transplantation therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Presented in part at Tandem BMT Meetings, Keystone, CO, February 12, 2005.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nurses, nurse practitioners, nurse coordinators, social workers, physical, speech, and occupational therapists, and other allied health care professionals for their dedication and outstanding care, and Ms Angela Norman for assistance in manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HB-67138 (J.K.), N01-HB-67132 (S.L.C.), N01-HB 67139 (J.E.W.), and N01-HB 67135 (N.K.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.K., S.L.C., J.E.W., S.A.F., E.C.G., and N.K. were principal investigators on the COBLT study and responsible for conceptualization of the study, collection of clinical data, primary analysis and interpretation of the data, and writing and editing the manuscript; J.K. was the principal investigator responsible for the initial analysis and interpretation of data as well as writing and editing the manuscript; V.K.P. was involved with analysis and interpretation of the data and writing and editing of the manuscript; L.A.B.-L. was a member of the steering committee and was involved in the conceptualizing and planning of the HLA part of the study (her laboratory provided prospective and retrospective HLA typing and was involved in auditing the HLA data); D.W. was involved with analysis and interpretation of the data; E.L.W. was involved with oversight of and collection of clinical data and preparation and review of the manuscript; and N.A.K. was chair of the COBLT steering committee and was involved in conceptualizing the study, analyzing and interpreting the data, and editing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joanne Kurtzberg, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3350, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: kurtz001@mc.duke.edu.