Abstract

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are often found in human tumors; however, their functional characteristics have been difficult to evaluate due to low cell numbers and the inability to adequately distinguish between activated and Treg cell populations. Using a novel approach, we examined the intracellular cytokine production capacity of tumor-infiltrating T cells in the single-cell suspensions of enzymatically digested tumors to differentiate Treg cells from effector T cells. Similar to Treg cells in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals, tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells, unlike FOXP3− T cells, were unable to produce IL-2 and IFN-γ upon ex vivo stimulation, indicating that FOXP3 expression is a valid biological marker for human Treg cells even in the tumor microenvironment. Accordingly, we enumerated FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in intratumoral and peritumoral sections of metastatic melanoma tumors and found a significant increase in proportion of FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in the intratumoral compared with peritumoral areas. Moreover, their frequencies were 3- to 5-fold higher in tumors than in peripheral blood from the same patients or healthy donors, respectively. These findings demonstrate that the tumor-infiltrating CD4 Treg cell population is accurately depicted by FOXP3 expression, they selectively accumulate in tumors, and their frequency in peripheral blood does not properly reflect tumor microenvironment.

Introduction

Regulatory CD4 T (Treg) cells comprise 5% to 10% of peripheral CD4 T cells, constitutively express IL-2Rα chain (CD25), and possess potent suppressive activity in vitro in mice and humans.1,2 The forkhead winged-helix transcription factor, FOXP3, has been shown to be the lineage marker for murine CD4 Treg cells,3,4 yet its role as a lineage marker in human Treg cells is unclear.5 Mutations in FOXP3 leads to a lymphoproliferative syndrome in both mice6 and humans,7 suggesting that expression of FOXP3 is crucial for the function of human CD4 Treg cells as it is in mice. However, recent studies have reported that FOXP3 expression can be up-regulated in human CD4 and CD8 T cells following in vitro activation.5,8-10 Although some studies suggest that FOXP3 expression confers a suppressive phenotype in activated human T cells,8,11 other studies demonstrate that activation-induced FOXP3+ T cells, unlike natural CD4 Treg cells, produce effector cytokines, and therefore do not represent Treg cells despite FOXP3 expression.9,10 In fact, IL-2 and IL-15 have been implicated in mediating FOXP3 expression in non-Treg cells during an in vitro activation, and the removal of these cytokines results in down-regulation of FOXP3 in the activated T-cell population.10

The significant role of CD4 Treg cells in suppressing antitumor immune responses has been well documented for murine tumors.2,12,13 However, the possible implication of CD4 Treg cells in down-modulating antitumor immune responses in humans is under intense investigation. A number of studies have reported a rise in circulating CD4 Treg cells in patients with various cancers.14-17 However, these studies were performed prior to the development of the FOXP3 monoclonal antibody; thus, CD4 Treg cells could not be accurately enumerated on a single-cell level for FOXP3 expression.

In the present study, we investigated the presence of CD4 Treg cells in tumors and peripheral blood of patients with metastatic melanoma. We used a novel approach to functionally distinguish between CD4 Treg cells and effector T cells that may transiently express FOXP3 in tumor-infiltrating T-cell populations. Thus, we evaluated the functional properties of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ CD4 T cells ex vivo and found that they share similar phenotypic and functional characteristics with FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells found in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. We further demonstrate that there is a selective increase in the frequency of intratumoral CD4 Treg cells compared with those in peritumoral regions, suggesting a selective migration and/or expansion of CD4 Treg cells among tumor cells. The frequency of CD4 Treg cells was significantly increased in tumors compared with peripheral blood from the same patients or healthy donors, indicating that enumeration of circulating CD4 Treg cells underestimates the accurate assessment of CD4 Treg cells in tumors.

Methods

Patients, PBMCs, and tumor samples

Tumor specimens and peripheral blood samples were collected from patients with metastatic melanoma. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with metastatic melanoma (n = 24) and healthy donors (n = 12) were obtained as either leukapheresis or blood draws and were prepared over Ficoll-Hypaque (LSM; MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) gradient and cryopreserved until analyzed. Tumor specimens from patients with melanoma (n = 26) were processed by sterile mechanical dissection followed by enzymatic digestion as previously described.18 Single-cell suspensions were filtered and separated on Ficoll-Hypaque gradient and cryopreserved until analyzed. Tumor specimens from 22 patients with metastatic melanoma whose tumor-infiltrating T cells resulted in an objective clinical response (n = 12) or no response (n = 10) were evaluated by immunohistochemistry in a double-blinded fashion to enumerate the frequency of CD4 Treg cells in the intratumoral and peritumoral sections. Specimens from 2 patients (one responder and one nonresponder) were excluded due to lack of immunostaining and internal positive controls. In some patients (n = 4), more than a single tumor was used to generate the treatment tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs); as a result, all of these tumors were analyzed separately by immunohistochemistry, and their averaged numbers are reported. Tumor samples from 9 patients were analyzed both by immunohistochemistry and single-cell fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analyses to confirm FOXP3 staining by both methods. In general, patients had a wide range of prior therapies that might have included 2 or more of the following treatments: surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, or none of the above. A table with patients' characteristics is given in Table S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Antibodies and reagents

The following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific for human antigens were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA): PerCP-conjugated anti-CD3 (SK7), FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 (SK1), and PE-conjugated anti-CD25 (2A3), anti-CD27 (M-T271), anti-CD127 (hIL-7R-M21), anti–IFN-γ (25723.11), anti–IL-2 (MQ1–17H12), anti–TNF-α, anti–IL-10 (JES3–19F1), and anti-CTLA (BNI3). Purified or allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human FOXP3 (PCH101) and its isotype control mAb were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Intracellular cytokine induction

Cryopreserved tumor digests and PBMCs were thawed into complete medium consisting of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Gemini Bio-Products, Calabasas, CA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Rockville, MD), 25 mM HEPES buffer (Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen). The complete medium was supplemented by 1% (10 μg/mL) DNase (Dornase Alfa Pulmozyme; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) to prevent cell clumping in tumor digests. T cells were stimulated with or without PMA (2 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1 μM) in the presence of 1 μM monensin (GolgiStop; BD Biosciences) for 6 to 8 hours. Cells were then spun down and resuspended in complete medium and stained for surface markers followed by fixation with Fix/Perm solution (eBioscience) for 40 to 50 minutes. Cells were washed once with staining buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 3% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) and stored at 4°C overnight prior to intracellular staining.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells were resuspended in staining buffer (PBS containing 3% FBS) and blocked with mouse IgGs (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) for 15 to 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were stained with PerCP-conjugated anti-CD3, FITC-conjugated anti-CD8, and PE-conjugated mAbs against surface antigens for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark. Cells were subsequently washed in staining buffer twice prior to fixation and permeabilization using eBioscience's buffers for intracellular staining of FOXP3 and CTLA-4 according to the manufacturer's instrutctions. Cells were run on a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto flow cytometry instruments (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using CellQuest (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo (Figure 5; TreeStar, Ashland, OR) software. The quadrants were set based on isotype control antibody staining, and the number in each quadrant represents the percentage of cells.

Immunohistochemical analysis

The detailed procedure has previously been described.19 Briefly, paraffin-embedded sections were cut, followed by paraffin removal, and were blocked to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific binding. Slides were incubated with rat anti-human FOXP3 antibody (clone PCH101, dilution 1:1000; eBioscience) for 30 minutes, followed by rabbit anti-rat antibody and the ABC peroxidase detection system (Vectastain Elite Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) using 3–3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) as a brown peroxidase substrate. The slides were subsequently incubated with either anti-human CD4 (clone 1F6, dilution 1:25; Novocastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom) or CD8 mAb (clone C8/144B, dilution 1:100; Dako) for 30 minutes, followed by detection using a horse anti-mouse secondary antibody and the ABC alkaline phosphatase system (Vector Laboratories). Tonsil tissues were used as positive and negative controls. For negative controls, rat IgG2a mAb (eBioscience) and mouse IgG1 (Dako) were substituted as the primary antibodies. A total of 10 independent fields with the most abundant TILs were selected under the microscope (Olympus BX51; Tokyo, Japan) using objective lenses 40×/0.75 without imaging medium. Each field was digitally photographed using a digital camera (Olympus DP71) and counted semiautomatically using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Only cells with morphologic features of lymphocytes were counted to exclude macrophages. Lymphocytes in the fibrous tissue were counted as peritumoral (stromal), and lymphocytes between at least 2 tumor cells were counted as intratumoral. The total number of CD8+, CD4+, FOXP3+, and double-staining cells were counted in 10 high-power fields for each sample in a double-blinded fashion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons of the frequencies of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in healthy individuals and patients with melanoma (Figure 1B) were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To compare the frequencies of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) versus tumors (Figure 1C) and in the intratumoral versus peritumoral sections for each patient (Figure 6B), paired t test was used. P values less than or equal to .05 were considered significant.

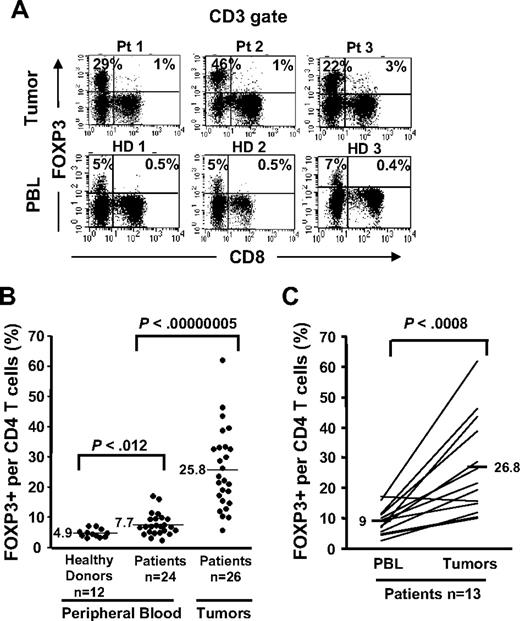

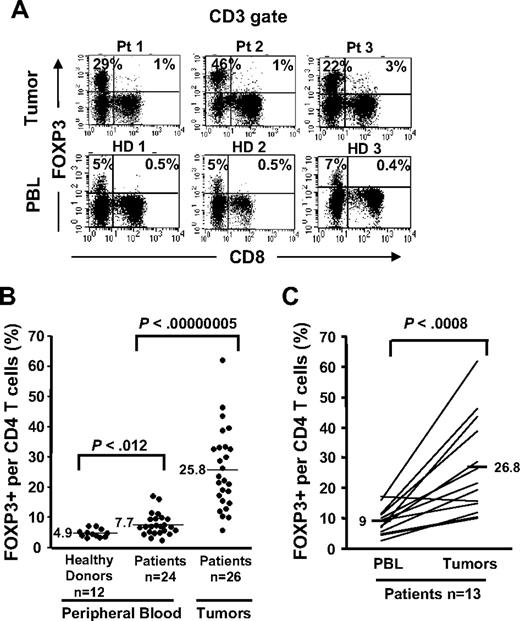

Selective accumulation of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors compared with PBLs. Cryopreserved tumor digests from 3 patients with metastatic melanoma (Pt) and PBLs from 3 healthy donors (HD) were thawed and immediately stained with CD3, CD8, and FOXP3 mAbs. (A) The dotplots were gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. The quadrants were set based on the isotype control Abs. The percentage for each quadrant represents the fraction of FOXP3+ T cells in CD8 T cells (top right quadrant) or in CD4 T cells (top left quadrant). CD3+CD8− T cells were considered CD4 T cells throughout the study. (B) The percentage of FOXP3+CD4 T cells per total CD4 T-cell population is quantified in PBLs from healthy donors (n = 12) and from patients with melanoma (n = 24) and in tumor digests (n = 26) using FACS analyses. (C) The percentage of FOXP3+CD4 T cells per total CD4 T cells in PBLs and tumors from the same patients (n = 13) were enumerated as described earlier.

Selective accumulation of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors compared with PBLs. Cryopreserved tumor digests from 3 patients with metastatic melanoma (Pt) and PBLs from 3 healthy donors (HD) were thawed and immediately stained with CD3, CD8, and FOXP3 mAbs. (A) The dotplots were gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. The quadrants were set based on the isotype control Abs. The percentage for each quadrant represents the fraction of FOXP3+ T cells in CD8 T cells (top right quadrant) or in CD4 T cells (top left quadrant). CD3+CD8− T cells were considered CD4 T cells throughout the study. (B) The percentage of FOXP3+CD4 T cells per total CD4 T-cell population is quantified in PBLs from healthy donors (n = 12) and from patients with melanoma (n = 24) and in tumor digests (n = 26) using FACS analyses. (C) The percentage of FOXP3+CD4 T cells per total CD4 T cells in PBLs and tumors from the same patients (n = 13) were enumerated as described earlier.

Results

Preferential accumulation of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumor relative to blood

In an effort to enumerate CD4 Treg cells in melanoma tumors, we initially used FOXP3 transcription factor assessed by FACS analysis as the surrogate marker for Treg cells. FOXP3 expression was readily detected in the tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T-cell population but not in CD8+ T cells. A high percentage of CD4 T cells in the tumors expressed FOXP3 (mean, 25.8%; range, 5.8%-61.8%, n = 26; Figure 1A,B) that was highly significant (P < .001; Wilcoxon) compared with the frequency of FOXP3+CD4 T cells found in the peripheral blood samples from patients with melanoma (mean, 7.7%; range, 2.5%-17.1%; n = 24) or healthy donors (mean, 4.9%; range, 3.2%-7.2%; n = 12; Figure 1B). The frequencies of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in patient PBLs (mean, 9%; range, 2.5%-17.1%) were significantly (n = 13; P < .001, paired t test) lower compared with their own tumors (mean, 26.8%; range, 10%-61.8%; Figure 1C). Similar to previous reports by us and other investigators, only a minuscule fraction of CD8 T cells in tumors19 or the peripheral circulation9,10 expressed FOXP3 (1%-3%; Figure 1A top right quadrant, tumor vs PBL). Moreover, we found a slight yet significant increase (P < .012, Wilcoxon) in the frequency of circulating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in patients with metastatic melanoma (mean, 7.7%; range, 2.5%-17.1%; n = 24) compared with healthy individuals (mean, 4.9%; range, 3.2%-7.2%; n = 12).

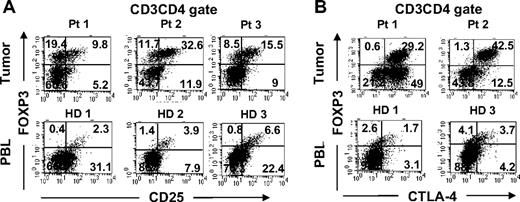

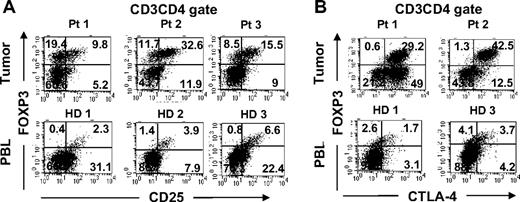

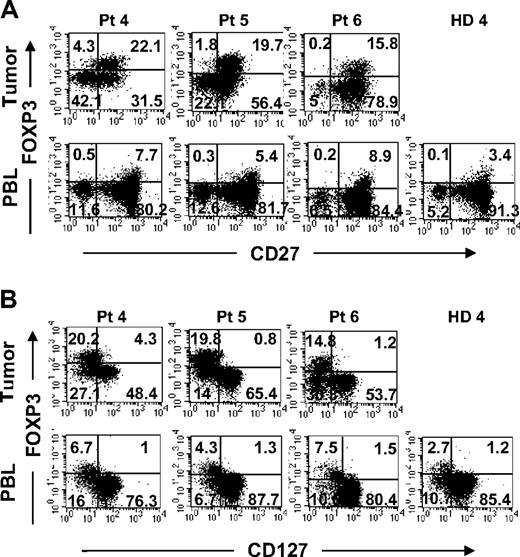

Tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells and circulating Treg cells in peripheral blood share similar phenotype

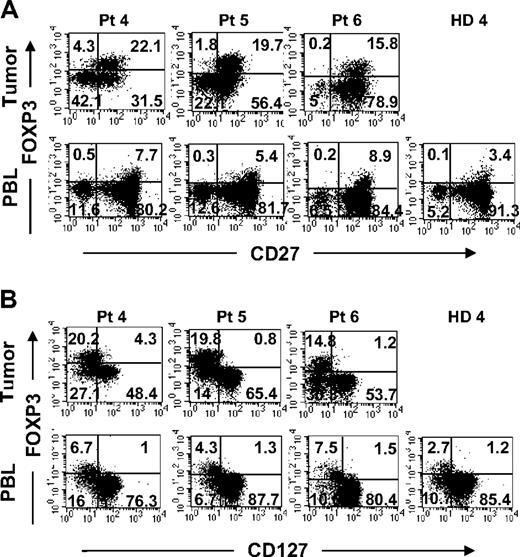

We next examined the phenotype of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells and compared them with Treg cells found in the circulation. A fraction of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells coexpressed CD25 similar to circulating Treg cells in healthy donor PBLs (Figure 2A). In addition to CD25 expression, tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells also coexpressed CTLA-4, a marker that is often expressed by Treg cells in peripheral blood (Figure 2B). In fact, the majority of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in the tumor expressed high levels of CTLA-4, whereas FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in the PBLs of healthy donors were heterogeneous for CTLA-4 expression. A fraction of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3−CD4 T cells also expressed CTLA-4, suggesting that they had undergone activation. In addition to the coexpression of CD25 and CTLA-4, tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells also expressed CD27 and lacked expression of IL-7Rα chain (CD127) at levels similar to FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in peripheral blood from the same patients or healthy donors (Figure 3). Overall, the tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells exhibited phenotypic characteristics similar to that of circulating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in healthy individuals.

Phenotypic comparison of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors versus peripheral blood in healthy donors. Tumor digests from patients and peripheral blood samples from healthy donors were thawed and immediately stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with either (A) anti-CD25 or (B) anti–CTLA-4 mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3CD4 (CD3+CD8−) T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of CD4 T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of several independent experiments using tumor digest samples (n = 26) and PBL samples from the same patients (n = 9) and healthy donors (n = 5).

Phenotypic comparison of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors versus peripheral blood in healthy donors. Tumor digests from patients and peripheral blood samples from healthy donors were thawed and immediately stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with either (A) anti-CD25 or (B) anti–CTLA-4 mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3CD4 (CD3+CD8−) T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of CD4 T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of several independent experiments using tumor digest samples (n = 26) and PBL samples from the same patients (n = 9) and healthy donors (n = 5).

Comparison of surface expression of CD27 and CD127 on FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors versus peripheral blood from the same patients. Tumor digests and peripheral blood from patients were thawed and immediately stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with either (A) anti-CD27 or (B) anti-CD127 mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3CD4 (CD3+CD8−) T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of CD4 T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of multiple independent experiments using tumor digest (n = 19) and PBLs (n = 9) samples from the same patients with metastatic melanoma.

Comparison of surface expression of CD27 and CD127 on FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors versus peripheral blood from the same patients. Tumor digests and peripheral blood from patients were thawed and immediately stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with either (A) anti-CD27 or (B) anti-CD127 mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3CD4 (CD3+CD8−) T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of CD4 T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of multiple independent experiments using tumor digest (n = 19) and PBLs (n = 9) samples from the same patients with metastatic melanoma.

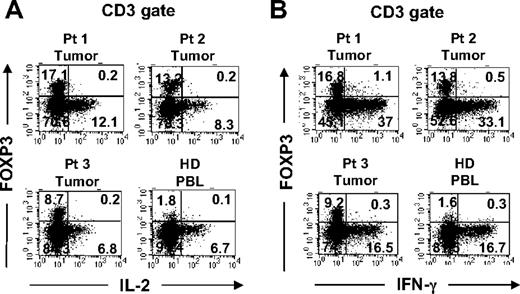

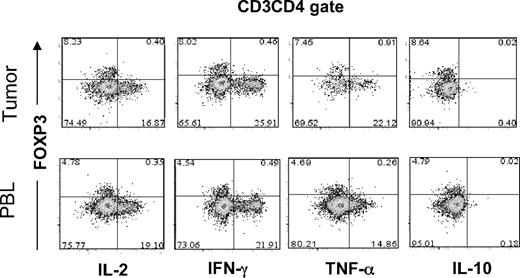

Functional characterization of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells

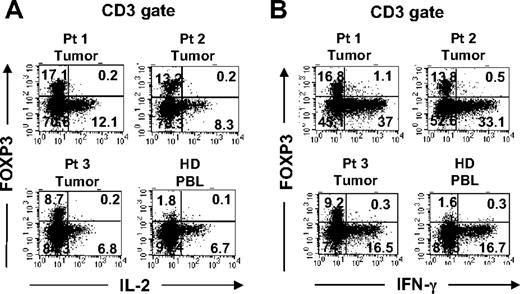

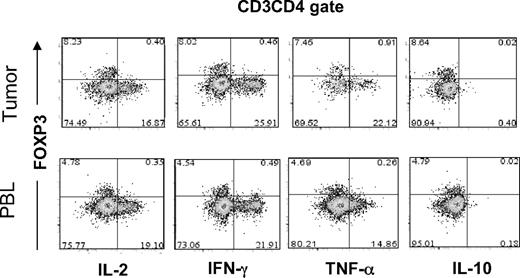

Recent reports have demonstrated that in vitro activation is sufficient to induce the up-regulation of CD25 and FOXP3 expression by CD25−FOXP3− T cells.9,10 Having found elevated percentages of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in melanoma tumors that preferentially expressed the T-cell activation–associated marker CTLA-4, the possibility existed that some or all of the intratumoral FOXP3+CD4 T cells were in fact tumor-activated effector cells. One hallmark of genuine Treg cells is their innate ability to suppress the activation of other T cells. Since the numbers of tumor-infiltrating T cells were limited, we could not examine the potential suppressive ability of these cells in a typical in vitro suppression assay. Another intrinsic characteristic of Treg cells is their relative inability to produce and secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-2 as previously shown in murine Treg cells.20,21 Therefore, we applied a novel approach that uses a small number of tumor-infiltrating T cells ex vivo to determine whether the tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T-cell population functionally represented Treg cells or activated T cells. Tumor-infiltrating T cells in tumor digests were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (PMA/I) for a short period of time in the presence of monensin to trap cytokines for intracellular detection. As demonstrated in Figures 4A and 5, tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells were unable to produce IL-2 in response to strong stimulation with PMA/I, similar to FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in peripheral blood in healthy donors. In contrast to FOXP3+CD4 T cells, tumor-infiltrating as well as peripheral blood T cells that lacked FOXP3 expression produced IL-2, serving as an internal positive control to confirm that the potential for T-cell activation by PMA/I existed (Figures 4A and 5). Thus, the inability to produce IL-2 correlated with FOXP3 expression both in tumor infiltrating cells and circulating peripheral blood T cells in patients (Figure 5) and healthy donors (Figure 4). Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells also lacked the ability to produce IFN-γ following stimulation with PMA/I, similar to their peripheral blood counterparts in healthy donors (Figure 4B) and patient PBLs (Figure 5). However, both tumor-infiltrating and peripheral blood T cells that lacked FOXP3 expression were able to produce IFN-γ, indicating that the ability to produce IFN-γ was not lost by all tumor-infiltrating T cells but only by FOXP3+CD4 T cells. In addition to IL-2 and IFN-γ, we examined whether FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors and peripheral blood were capable of producing other cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-10. In contrast to FOXP3−CD4 T cells, both tumor-infiltrating and peripheral blood FOXP3+CD4 T cells from patients were incapable to produce TNF-α following PMA/I stimulation (Figure 5). Using intracellular staining, we could not detect any IL-10 produced by either FOXP3+ or FOXP3− CD4 T cells. As demonstrated in this study, this anergic functional phenotype of FOXP3+CD4 T cells was not unique to tumor-infiltrating T cells; circulating FOXP3+CD4 T cells were also anergic to PMA/I stimulation in healthy donor (Figure 4) as well as patient peripheral blood (Figure 5), indicating that functional anergy is a general phenomenon of Treg cells whether in the tumor or peripheral blood. Based on the intracellular functional assessment, we conclude that FOXP3+CD4 T cells found in tumors functionally resemble Treg cells that reside in the peripheral blood. Therefore, FOXP3 expression is a valid surrogate marker for identifying intratumoral Treg cells ex vivo.

Functional comparison of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors versus peripheral blood. Tumor digests from patients and peripheral blood samples from healthy donors were thawed and immediately stimulated with PMA/I for 6 to 8 hours in the presence of monensin. Cells were subsequently stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with either (A) anti–IL-2 or (B) anti–IFN-γ mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3+ T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of multiple independent experiments using tumor digest samples from different patients (n = 26) and PBL samples from healthy donors (n = 3) and the same patients (n = 5; Figure 5).

Functional comparison of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumors versus peripheral blood. Tumor digests from patients and peripheral blood samples from healthy donors were thawed and immediately stimulated with PMA/I for 6 to 8 hours in the presence of monensin. Cells were subsequently stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with either (A) anti–IL-2 or (B) anti–IFN-γ mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3+ T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of multiple independent experiments using tumor digest samples from different patients (n = 26) and PBL samples from healthy donors (n = 3) and the same patients (n = 5; Figure 5).

Functional comparison of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumor versus peripheral blood in the same patient. Tumor digests and peripheral blood samples from patients with metastatic melanoma were thawed and immediately stimulated with PMA/I for 6 to 8 hours in the presence of monensin. Cells were subsequently stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with anti–IL-2, anti–IFN-γ, anti–TNF-α, or anti–IL-10 mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3CD4 (CD3+CD8−) T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of CD4 T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of multiple independent experiments using tumor digest samples from different patients (n = 8) and PBL samples from the same patients (n = 5).

Functional comparison of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in tumor versus peripheral blood in the same patient. Tumor digests and peripheral blood samples from patients with metastatic melanoma were thawed and immediately stimulated with PMA/I for 6 to 8 hours in the presence of monensin. Cells were subsequently stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, and anti-FOXP3 mAb along with anti–IL-2, anti–IFN-γ, anti–TNF-α, or anti–IL-10 mAbs. The dotplots were gated on CD3CD4 (CD3+CD8−) T cells. The numbers represent the percentages of CD4 T cells in each quadrant. These results are representative of multiple independent experiments using tumor digest samples from different patients (n = 8) and PBL samples from the same patients (n = 5).

Selective accumulation of FOXP3+CD4 T cells in intratumoral as compared to peritumoral sections in metastatic melanoma tumors

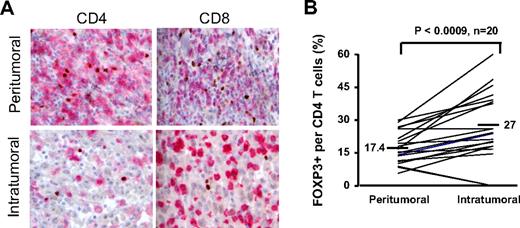

Having determined that tumor-infiltrating CD4 T cells that expressed FOXP3 phenotypically and functionally resembled Treg cells, we used FOXP3 expression as the biological marker for enumerating Treg cells in tumors. Using immunohistochemical analysis, we enumerated the number of Treg cells in the intratumoral versus peritumoral sections of 20 patients with melanoma. FOXP3 expression was confined to CD4 T cells and not CD8 T cells (Figure 6A; Table 1), consistent with the observation in peripheral blood and tumor digests via flow cytometry (Figure 1A). More important, fewer CD4+ T cells were present in the intratumoral regions than in the peritumoral regions (Table 1); however, the percentages of FOXP3+CD4+ Treg cells were significantly (P < .001, paired t test) increased in the intratumoral regions (mean 27%) compared with peritumoral regions (mean 17.4%) from the same patients (Figure 6B).

Enumerating FOXP3+ T cells within peritumoral and intratumoral sections using immunohistochemical analysis. Metastatic melanoma lesions from 20 patients were analyzed by immunhistochemistry to enumerate the number of FOXP3+ T cells in the intratumoral and peritumoral (stromal) areas in metastatic melanoma tumors. (A) CD4 (first column) and CD8 (second column) were visualized in pink and FOXP3 staining of nucleus was depicted in brown; ×40 magnification was used. (B) The percentage of FOXP3+CD4 T cells per total CD4 T-cell population in the intratumoral and peritumoral sections were calculated for each patient. The paired t test was used to compare between intratumoral and peritumoral sections.

Enumerating FOXP3+ T cells within peritumoral and intratumoral sections using immunohistochemical analysis. Metastatic melanoma lesions from 20 patients were analyzed by immunhistochemistry to enumerate the number of FOXP3+ T cells in the intratumoral and peritumoral (stromal) areas in metastatic melanoma tumors. (A) CD4 (first column) and CD8 (second column) were visualized in pink and FOXP3 staining of nucleus was depicted in brown; ×40 magnification was used. (B) The percentage of FOXP3+CD4 T cells per total CD4 T-cell population in the intratumoral and peritumoral sections were calculated for each patient. The paired t test was used to compare between intratumoral and peritumoral sections.

A total of 20 tumor samples evaluated in our study had been resected from patients who later went on to receive adoptive transfer of autologous ex vivo–expanded TILs and IL-2 administration following lymphodepleting preconditioning22 ; 11 patients experienced an objective clinical response, and 9 patients were nonresponsive to this therapy. To evaluate if an association existed between the response to adoptive immunotherapy and the frequency of intratumoral FOXP3+CD4+ Treg cells in tumors collected prior to treatment, we enumerated FOXP3+CD4+ T cells in tumors from responding and nonresponding patients. We did not find a significant difference between the percentage or number of FOXP3+CD4+ Treg cells found in tumors of patients that were responsive (n = 11) to TIL treatment compared with nonresponsive (n = 9) patients (Table 1). Interestingly, there was a trend toward increased numbers of both CD8 and CD4 T cells in tumors from patients that went on to experience an objective response. Although there was a slight increase in the total number of intratumoral CD8 T cells in tumors that gave rise to treatment TILs resulting in an objective clinical response (mean, 263 ± 53) compared with nonresponders (mean, 170 ± 54), these differences were not significant (P = .1, Wilcoxon nonparametric test).

Discussion

In this study, we used a novel approach to functionally distinguish between CD4 Treg cells and effector T cells, and found that tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells shared phenotypic and functional characteristics with circulating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in healthy individuals. Therefore, we conclude that FOXP3 can be used as the surrogate marker for identifying CD4 Treg cells even in the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, we found a significant increase in the frequency of CD4 Treg cells in tumors compared with peripheral blood in patients with metastatic melanoma. In fact, the enrichment of CD4 Treg cells was more pronounced in the intratumoral than peritumoral (stromal) areas in the tumor microenvironment, suggesting a selective accumulation of CD4 Treg cells in the vicinity of tumor cells. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to phenotypically and functionally characterize small numbers of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells ex vivo without additional in vitro expansion, which can have an impact on the expression of FOXP3 in T cells as well as alter their initial phenotype and function.

In our study, we found that tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 T cells phenotypically resembled peripheral FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in healthy donors. Not only did they express CD25 and CTLA-4, they also shared a similar phenotype (CD27+CD127−/low) with the peripheral blood CD4 Treg cells. Human FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells are known to express CD25 and CTLA-423 as well as CD27,24 and they are also known to lack expression of CD127 (IL-7Rα chain).25,26 It is interesting that CTLA-4 was expressed by primarily all FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in tumors but not in peripheral blood, suggesting that tumor-infiltrating Treg cells may possess a more activated and potent suppressive function. Functionally, the tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells were anergic to stimulation with PMA and ionomycin; they were incapable of producing effector cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, whereas the tumor-infiltrating FOXP3−CD4 T cells produced these effector cytokines. These results indicate that tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells were activated Treg cells and not effector T cells. Although their suppressive function were not assessed using a typical suppression assay due to limited number of viable T cells present in tumor digests, we propose that the functional assay applied in this study is sufficient to assess the function of Treg cells at a single-cell level.

In recent years, a number of studies have reported an increase in the number of CD4 Treg cells in PBLs, draining lymph nodes, and tumor tissues in patients with various cancers.14-17,27,28 Many of these studies were performed prior to the development of the FOXP3 mAb and were thus limited to detection of FOXP3 mRNA levels at the cell population and not at the single-cell level, which can enumerate the number of FOXP3+ T cells. Other studies relied on the expansion of tumor-infiltrating T cells with IL-2 to isolate tumor-antigen–specific CD4 T cells that were claimed to have a suppressive function.29,30 IL-2 is a T-cell growth factor that is widely used for in vitro T-cell expansion and cloning; however, IL-2 has recently been demonstrated to induce the de novo expression of FOXP3 in nonregulatory T cells that exhibited effector function.10 The current study is unique because it characterized tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T cells both at a phenotypic and functional level ex vivo without in vitro cell expansion that may alter their initial phenotype and function. In addition, our study evaluated the presence of FOXP3+ T cells in the intratumoral and peritumoral areas in metastatic melanoma legions and found a selective accumulation of CD4 Treg cells among tumor cells (intratumoral) as compared with stromal tissue (peritumoral) and peripheral blood in the same patients. The differential distribution of CD4 Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment indicates that accumulation of Treg cells in tumors is selective. Our study further underlines a significant role for tumors to recruit CD4 Treg cells that may subsequently contribute to an immune suppression of antitumor immune responses within the tumor microenvironment.

We found an overall increase in the total number of tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells in the intratumoral sections in patients with metastatic melanoma that had objective clinical response to TIL treatment compared with nonresponders; however, this difference was not significant. In patients with ovarian cancer, a favorable clinical association was found with a high ratio of CD8 T cells infiltrating into tumors.31 Although the kinetics and migration of CD8 T cells infiltrating into melanoma tumors may differ with the ovarian tumors, it is also likely that a difference in patient selection may account for this difference. The patient tumors that were selected for our immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis included tumors that gave rise to TIL cultures with in vitro tumor reactivity and did not include patients whose tumors failed to generate active TIL cultures. Perhaps a larger number of patients without the current criteria may reveal a similar association as was found in patients with ovarian cancer. Furthermore, we did not find a significant increase in the proportion of intratumoral FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells between patients whose active TIL infusion resulted in an objective clinical response versus those who did not. These results indicate that there is no significant difference in the proportion of intratumoral CD4 Treg cells in tumors that gave rise to active TIL cultures regardless of the clinical outcome. Although our initial objective was to evaluate the proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD4 Treg cells between responders and nonresponders, it would be interesting to determine whether there is any association between the proportion of intratumoral FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells with patients' survival and the ability to grow active TIL cultures among a larger number of patients with metastatic melanoma.

In agreement with earlier studies that either used CD25 in patients with pancreatic or breast adenocarcinoma15 or FOXP3 in patients with leukemia32 to enumerate CD4 Treg cells, we also found a slight yet significant increase (P < .012) in the frequency of circulating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in patients with metastatic melanoma compared with healthy individuals. It is postulated that the relative increase in circulating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in patients with cancer is driven by lymphopenia following chemotherapy32 or other treatments such as administration of IL-2.33,34 However, our findings indicate that the frequency of CD4 Treg cells in the peripheral blood does not accurately reflect their proportion in the tumor as determined by a significantly greater proportion of FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in tumors than in peripheral blood from the same patients (P < .001).

The mechanism(s) responsible for this selective accumulation of CD4 Treg cells in tumors is currently unknown. Chemokines and chemokine receptors have been postulated to play a role in the recruitment of CD4 Treg cells into the tumor microenvironment.27 Tumor-derived CD4 Treg cells can express CCR4, the chemokine receptor for CCL22, which is produced by tumors and tumor-infiltrated macrophages as demonstrated in patients with ovarian cancers.16,27 Whether expression of CCR4 or other chemokine receptors play a role in the trafficking of human CD4 Treg cells into melanoma legions is yet to be resolved. In addition, the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment may promote the expansion of natural CD4 Treg cells as well as de novo generation of induced CD4 Treg cells within the tumor, as indicated in animal models.35,36 For instance, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) produced by melanoma cells37 may induce expansion of CD4 Treg cells within tumors, as it has been demonstrated for peripheral blood CD4 Treg cells in vitro.38 Furthermore, TGF-β has been extensively described to convert nonregulatory CD4 T cells into Treg cells in mice.39-41 Whatever the underlying mechanism(s) for accumulation of human CD4 Treg cells in tumor is, the increased proportion of intratumoral FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells is likely to inhibit the cytolytic function of tumor-infiltrating effector T cells and undermine their antitumor immune responses.

The ability to selectively deplete CD4 Treg cells in vivo has the potential to augment the antitumor immune response and achieve a clinical response in patients with cancer. Clinical approaches for the selective depletion of Treg cells in vivo are numerous and include the adoptive transfer of CD25-depleted T cells after lymphodepletion,42 the use of IL-2R–directed cytotoxins (denileukin diftitox),43 and administration of CD25-directed immunotoxins.19 In our previous clinical trial, administration of LMB-2, a CD25-directed immunotoxin, to patients with metastatic melanoma caused a transient partial reduction in both circulating and intratumoral CD4 Treg cells; however, the effectiveness of vaccination against shared tumor antigen was not enhanced in these patients.19 Others have reported that Treg cell depletion prior to vaccination can improve tumor-specific T-cell responses in patients with cancer;44 however, the ability to induce objective cancer regression in these and other trials of Treg cell depletion has uniformly been disappointing and requires further investigation and optimization. An alternative approach to depletion of Treg cells is to inactivate them by engaging costimulatory molecules such OX40, which subsequently can lead to inhibition of Treg cell suppression as recently demonstrated in a murine tumor model.45 The translation of these observations in patients with cancer awaits clinical trials.

In conclusion, we used a novel functional assay to differentiate between Treg cells and activated T cells in melanoma tumors ex vivo without long-term culturing in T-cell growth factors such as IL-2. Our findings conclusively point to FOXP3 as the biological marker to identify human CD4 Treg cells ex vivo. Using the combination of phenotypic and functional parameters, we found that the frequency of FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells in tumors is significantly higher than the peripheral blood in the same patients. Furthermore, the frequency of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+CD4 Treg cells was significantly higher in the intratumoral than peritumoral areas within the tumor microenvironment. This novel observation demonstrates a hierarchy of CD4 Treg cell distribution within tumors and highlights the significant role of tumor and tumor microenvironment in recruitment and expansion of CD4 Treg cells in the tumor.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to A. Mixon and S. Farid for performing flow cytometry, D. White for statistical consultation and preparing the patient characteristics table, and Mark Dudley for assistance with patient sample selection.

Authorship

Contribution: M.A. designed and performed research and wrote the manuscript; A.F.S. performed all the immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses; B.H. assisted with performing functional assays; D.J.P. compiled the patients' IHC analysis; J.R.W. processed tumor digests; M.J.M. supervised the IHC analyses; and S.A.R. designed and supervised the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven A. Rosenberg or Mojgan Ahmadzadeh, Surgery Branch, NCI, NIH, CRC Building, Room 3W-3940, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: sar@nih.gov or mojgan_ahmadzadeh@nih.gov.