To the editor:

In their recent article in Blood,1 You et al hypothesized on the mechanism by which decoy receptor 3 (DcR3), a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family (TNF-R), could promote tumor growth in patients with cancer. They reported that DcR3 induces apoptosis of dendritic cells (DCs) by binding to their heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). They argued that the ensuing immune suppression would explain why high levels of DcR3 are associated with reduced survival in cancer patients. This effect of DcR3 was shown by using a recombinant form of DcR3 fused to the Fc portion of human IgG1 (DcR3-Fc). However, it is known that the Ig moiety of fusion proteins bind Fc receptors (FcR).2 Because DCs express high-affinity FcR3 that can produce a strong signal into cells,4 the results from You et al do not establish that, without this Ig-FcR interaction, the binding of DcR3 to HSPG is sufficient to induce DC apoptosis. As a consequence, it is not known whether the native form of DcR3 can be held responsible for reduced survival of cancer patients by inducing apoptosis in DCs or, alternatively, by its decoy activity on proapoptotic molecules such as Fas ligand.5

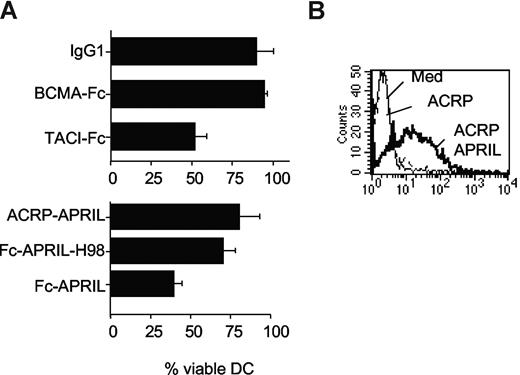

Using another member of the TNF-R family, the transmembrane activator, calcium modulator, and cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI)–Fc, we observed a similar inhibition of DC generation from peripheral blood monocytes (Figure 1A top) as reported by You et al with DcR3-Fc.1,6 It is noteworthy that TACI, like DcR3, has an HSPG-binding domain.7 By contrast, B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–Fc that binds the same ligands as TACI-Fc but has no HSPG binding domain7 and control IgG1 did not affect DC generation. Such inhibition of DC generation was also observed with a member of the TNF family, a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) also bearing an HSPG binding domain8 fused to the same Fc of IgG1 (Fc-APRIL; Figure 1A bottom). A mutant of the latter molecule without its HSPG binding domain, Fc-APRILH98,8 or the wild-type molecule oligomerized by a non-Ig moiety, the collagen domain of adiponectin, ACRP-APRIL,9 failed to inhibit DC generation in spite of binding to DC very efficiently (Figure 1B). Hence, binding to HSPG is essential, but an additional interaction with FcR is prerequisite to affect DCs.

HSPG and FcR cross-linking impair DC generation. (A) Peripheral blood monocytes were cultured in GMCSF/IL-4 in the presence of 10 μg/mL of the indicated reagents. After 6 days, the number of viable DCs in the culture was assessed by dye exclusion; 100% was arbitrarily defined as the number of DCs recovered from culture with medium alone. Error bars represent SD. (B) Binding of 10 μg/mL ACRP-APRIL on monocyte-derived DCs. ACRP alone served as a negative control.

HSPG and FcR cross-linking impair DC generation. (A) Peripheral blood monocytes were cultured in GMCSF/IL-4 in the presence of 10 μg/mL of the indicated reagents. After 6 days, the number of viable DCs in the culture was assessed by dye exclusion; 100% was arbitrarily defined as the number of DCs recovered from culture with medium alone. Error bars represent SD. (B) Binding of 10 μg/mL ACRP-APRIL on monocyte-derived DCs. ACRP alone served as a negative control.

The finding that simultaneous cross-linking of FcR and HSPG and/or bridging FcR and HSPG eliminates DCs and may cause immune suppression is of great interest. Indeed, any protein carrying an HSPG-binding domain fused to a Fc portion of IgG may achieve immunosuppression. Such immunosuppression is likely to constitute an advantage in the ongoing clinical trial with TACI-Fc in autoimmune disorders.10

Authorship

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Foundation Leenaards, and Dr Henri Dubois Ferrière-Dinu Lipatti Foundation.

Contribution: E.R. designed the research and contributed to the writing; P.S. performed experiments; and B.H. designed research, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Bertrand Huard, Division of Hematology, Geneva University Hospital, 1 Rue Michel Servet, Geneva, Switzerland 1211; e-mail: bertrand.huard@medecine.unige.ch.

References

National Institutes of Health