Abstract

Imatinib mesylate (IM), 400 mg daily, is the standard treatment of Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Preclinical data and results of single-arm studies raised the suggestion that better results could be achieved with a higher dose. To investigate whether the systematic use of a higher dose of IM could lead to better results, 216 patients with Ph+ CML at high risk (HR) according to the Sokal index were randomly assigned to receive IM 800 mg or 400 mg daily, as front-line therapy, for at least 1 year. The CCgR rate at 1 year was 64% and 58% for the high-dose arm and for the standard-dose arm, respectively (P = .435). No differences were detectable in the CgR at 3 and 6 months, in the molecular response rate at any time, as well as in the rate of other events. Twenty-four (94%) of 25 patients who could tolerate the full 800-mg dose achieved a CCgR, and only 4 (23%) of 17 patients who could tolerate less than 350 mg achieved a CCgR. This study does not support the extensive use of high-dose IM (800 mg daily) front-line in all CML HR patients. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00514488.

Introduction

The clinical development of imatinib mesylate (IM, previously known as STI571) was rapid. Because a phase 1 study had shown that IM was highly effective and well tolerated at a dose of 300 mg daily or higher,1 a dose of 400 mg daily was selected for a phase 2 study of patients with Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic phase (CP) who were resistant to or intolerant of interferon-alpha (IFNα),2 and for a phase 3 study of patients with previously untreated Ph+ CML in early CP, in which IM was compared with IFNα and low-dose cytarabine.3 These 2 studies led to approval, registration, and worldwide use of the drug (Gleevec or Glivec; Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) at a dose of 400 mg once daily. On the basis of 2 other studies of IM in patients with CML in accelerated phase (AP) and blastic phase (BP), the recommended daily dose for these patients in advanced phases was set at 600 mg daily,4,5 and the recommendation of increasing the IM dose to 600 and also 800 mg daily was rapidly extended also to patients in CP, in case of unsatisfactory response to 400 mg, or response loss. These recommendations were confirmed by a panel of experts appointed by European LeukemiaNet.6 Several prospective but nonrandomized studies reported that responses to IM were more rapid and better in the patients who were treated with 600 or 800 mg.7-10 Moreover, the interest on the best dosing of IM was fostered by other arguments, all favoring a dose increase, including the fact that the maximum tolerated dose had never been determined, that a higher blood drug level could neutralize the mechanisms limiting drug concentration in the target cells, and that several BCR-ABL kinase domain point mutations were still sensitive to IM at concentrations that can be easily achieved in vivo with higher IM doses. On the basis of these premises, we designed and performed a prospective randomized study comparing daily dosing of IM 800 mg with 400 mg front-line, for the treatment of patients with Ph+ CML in early CP. The study was limited to the patients who were high risk (HR) according to the Sokal prognostic classification,11 because it was already known that in HR patients the response to IM standard dose was inferior,12,13 and it was thought that in these patients there was more need for improvement.

Methods

Study population, design, and protocol

All patients, at least 18 years old, with Ph+ and BCR-ABL–positive CML in early CP (within 6 months from diagnosis and previously untreated or treated only with hydroxyurea), and HR according to the Sokal prognostic classification,11 were eligible, provided that the common eligibility criteria were met (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

The screening procedures included medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, chest x-ray, HCV/HBV/HIV serology, AST, ALT, bilirubin and creatinine, blood counts and differential, cytogenetics, and the determination of BCR-ABL transcripts type and level. Once the screening procedures were completed, the patient was randomly assigned to receive IM either 400 mg (once daily) or 800 mg (400 mg twice daily). The dose of IM was adapted according to side effects and toxicity, as reported in Table 1. The core trial time was 1 year, during which time the treatment was continued at the assigned dose, discontinued in case of adverse events (AEs; Table 1), or changed in case of failure. After 1 year, the dose of IM could be modified at investigators' discretion.

The protocol required a visit every month for 1 year, blood chemistry monthly; blood counts and differentials weekly for the first 3 months and monthly thereafter; a bone marrow aspirate with cytogenetics after 3, 6, and 12 months; and a quantitative determination of BCR-ABL transcripts level after 3, 6, and 12 months. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures were performed according to Good Clinical Practice and were approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions.

Definition of phase, risk, response, and failures

The accelerated/blast phase (AP/BP) was identified by a blood myeloblasts or myeloblasts and promyelocytes percentage of at least 10% or 30%, respectively, or by any extramedullary blast involvement, excluding spleen and liver.

The relative risk (RR) was calculated and defined according to Sokal et al11 as follows:

where EXP indicates exponential, age indicates age in years, spleen indicates the maximum distance (in centimeters) from the costal margin, platelet indicates platelet count (in × 109/L), and blasts indicates the percentage of myeloblasts in peripheral blood. Categories of RR are low (< 0.80), intermediate (0.80-1.20), and high (> 1.20).

The hematologic response (HR) and the cytogenetic response (CgR) were defined as previously reported1-3,6-10 (Table S2). The molecular response was defined as major (MMolR) if the BCR-ABL ratio was less than 0.10% on the International Scale (IS),14 whereby 0.10 is equal to a 3-log reduction from a standard baseline level as defined in the IRIS (International Randomized IFN vs ST1571) study.13

Treatment failures were originally defined as lack of complete hematologic response (CHR) at 6 months, or less than minor CgR at 6 months, or loss of CHR, or loss of complete cytogenetic response (CCgR). From 2006 on, the failure criteria of European LeukemiaNet were adopted6 (no HR at 3 months, less than CHR or no CgR at 6 months, less than partial cytogenetic response [PCgR] at 12 months, less than CCgR at 18 months, loss of CHR, loss of CCgR).

Cytogenetics

Cytogenetic studies were performed by chromosome banding analysis of at least 20 marrow cell metaphases, after short-term culture (24 or 48 hours or both) with standard G or Q banding techniques. Fluorescence–in situ hybridization (FISH) of interphase cells was not required, but it was recommended if less than 20 metaphases were evaluable and was performed with BCR-ABL extra-signal, dual-color, dual-fusion probes (Vysis LSI BCR-ABL Translocation Prob; Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, IL), or D-FISH probe (QBiogene, Montreal, QC). FISH was used only for the definition of CCgR, when the number of positive marrow cell interphase nuclei was less than 2 of 200 (< 1%).15-18 Cytogenetic data were not centrally reviewed.

BCR-ABL transcripts level

BCR-ABL transcripts level assessment was performed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-Q-PCR) according to suggested procedures and recommendations.14,19 BCR-ABL transcript levels were expressed as a percentage according to the IS,14 taking advantage of the ongoing international initiatives that allow researchers to standardize the quantitation of BCR-ABL transcripts through the use of a conversion factor and consequently to express their results according to the IS.19-22 The reference laboratories that performed most of the RT-Q-PCR analyses on this study and that were responsible for the validation of the results performed in local laboratories (Table S3) were located in Bologna (Italy), Orbassano-Turin (Italy), Uppsala (Sweden), Istanbul (Turkey), and Tel Hashomer (Israel). Representative samples were cross-checked among these laboratories. The materials, the reagents, and the methods that were used were developed within the international collaborative studies for the harmonization of BCR-ABL mRNA quantification which were performed according to Heidelberg-Mannheim20,22 and Adelaide19,21 laboratories.

Statistics

The primary hypothesis was that treatment with 800 mg IM would lead to a higher proportion of CCgR at 1 year. Therefore, the primary end point was a binary variable in which all randomly assigned patients were classified at 1 year as a CCgR or not, according to the intention-to-treat principle. From the IRIS study, the expected CCgR rate of HR patients after 12 months of treatment at 400 mg daily was 50%.13 To detect an absolute difference of 20% (a CCgR rate of 70% in the experimental arm), with a power 1-β of 80% and α of 0.05 two-sided, the number of patients to accrue was established as 100 for each treatment arm.23 All comparisons were made using the Student t test and the Yates corrected χ2 test, as appropriate. Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), failure-free survival (FFS), and event-free survival (EFS) were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method,24 from the date of the first IM dose to death (OS), to progression to AP or BP or death (PFS), to failure or death (FFS), and to any events, including treatment discontinuation for AEs or severe AE (SAE), failure, progression to AP or BP, or death, whichever came first (EFS).

Results

Two hundred sixteen eligible patients were enrolled during a 3-year period (March 2004 to April 2007). The main clinical and hematologic characteristics at diagnosis are reported in Table 2. The median follow-up time of living patients was 26 months in both arms (range, 13-51 months).

Treatment results are reported in Table 3. At 12 months the number of patients who were in CCgR was 69 (64%) of 108 in the high-dose arm and 63 (58%) of 108 in the standard-dose arm (P = .435). In addition, the number of failures and the number of patients who discontinued treatment for any reasons were not different. At 3 and 6 months, no difference between the 2 arms could be detected (Table 3).

Molecular response is shown in Table 4. At any time point the proportion of MMolR was slightly but nonsignificantly higher in the high-dose arm than in the standard-dose arm, and the BCR-ABL transcript levels were slightly but no significantly lower in the 800-mg arm than in the 400-mg arm.

The dose of IM that was actually taken, and the relation between that dose and the response, was calculated in all the patients who completed 1 year of treatment, or failed during the first year of treatment. In the high-dose arm, the median average daily dose was 720 mg, but there was a considerable spread from 800 to less than 350 mg daily (Table 5). The CCgR rate was highest (96%) in the 25 patients who could take the whole assigned 800-mg dose and was lowest (20%) in the 10 patients who could take only less than 400 mg daily. In the standard-dose arm, the median average daily dose was 400 mg, and the CCgR rate was 66% for those who took 100% of the dose (400 mg), and 77% for those who had a small dose reduction (350-399 mg; Table 5). Also in this arm, the CCgR rate of the patients who had a substantial dose reduction (< 350 mg daily) was low (27%).

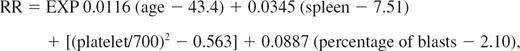

Overall survival. At 36 months the actuarial proportion of patients alive was 91% (95% CI, 87%-94%) in the high-dose arm (HDA) and 84% (95% CI, 78%-90%) in the standard-dose arm (SDA). P = .79, log-rank test. No patient was censored before last contact or death. Total number of deaths was 7 in the HDA and 8 in the SDA.

Overall survival. At 36 months the actuarial proportion of patients alive was 91% (95% CI, 87%-94%) in the high-dose arm (HDA) and 84% (95% CI, 78%-90%) in the standard-dose arm (SDA). P = .79, log-rank test. No patient was censored before last contact or death. Total number of deaths was 7 in the HDA and 8 in the SDA.

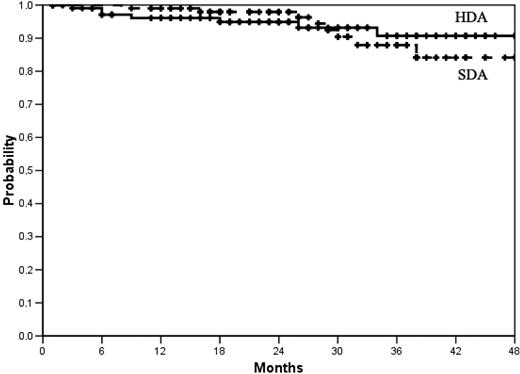

Survival-free from progression to AP or BP. At 36 months the actuarial proportion of patients alive and progression-free was 88% (95% CI, 84%-92%) in the high-dose arm (HDA) and 86% (95% CI, 82%-90%) in the standard-dose arm (SDA). P = .63 log-rank test. No patient was censored before last contact, death, or progression. Total number of progressions was 9 in the HDA and 11 in the SDA.

Survival-free from progression to AP or BP. At 36 months the actuarial proportion of patients alive and progression-free was 88% (95% CI, 84%-92%) in the high-dose arm (HDA) and 86% (95% CI, 82%-90%) in the standard-dose arm (SDA). P = .63 log-rank test. No patient was censored before last contact, death, or progression. Total number of progressions was 9 in the HDA and 11 in the SDA.

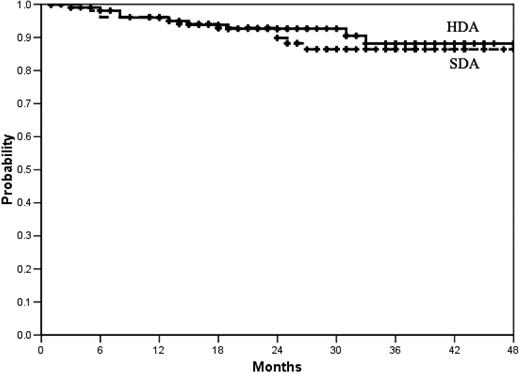

Failure-free survival. See “Methods” for the definition of failure. At 36 months the actuarial proportion of patients alive and failure-free was 72% (95% CI, 66%-78%) in the high-dose arm (HAD) and 74% (95% CI, 70%-78%) in the standard-dose arm (SDA). P = .66, log-rank test. The patients who dropped out or discontinued the treatment for AEs or SAEs were censored.

Failure-free survival. See “Methods” for the definition of failure. At 36 months the actuarial proportion of patients alive and failure-free was 72% (95% CI, 66%-78%) in the high-dose arm (HAD) and 74% (95% CI, 70%-78%) in the standard-dose arm (SDA). P = .66, log-rank test. The patients who dropped out or discontinued the treatment for AEs or SAEs were censored.

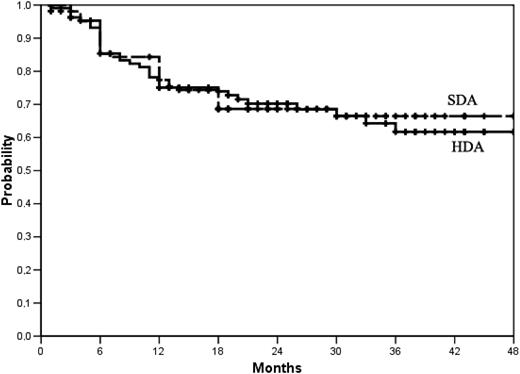

Event-free survival. Events were treatment discontinuation for AEs or SAEs, failure, progression to AP or BP, or death, whichever came first. At 36 months, the actuarial proportion of patients who were alive and event-free was 62% (95 CI, 56%-68%) in the high-dose arm (HDA) and 66% (95% CI, 61%-71%) in the standard-dose arm. P = .89, log-rank test.

Event-free survival. Events were treatment discontinuation for AEs or SAEs, failure, progression to AP or BP, or death, whichever came first. At 36 months, the actuarial proportion of patients who were alive and event-free was 62% (95 CI, 56%-68%) in the high-dose arm (HDA) and 66% (95% CI, 61%-71%) in the standard-dose arm. P = .89, log-rank test.

Discussion

This study represents the largest randomized study on therapy for HR patients with CML to date. Contrary to the expectation, we could not show a significant benefit of increased IM dose. The expectation was based on preclinical, clinical, and pharmacokinetic data. Although pharmacokinetic studies did not show a significant relation between the dose of IM, body weight, body surface, or age,25-28 in the IRIS study IM trough plasma levels ranged from less than 200 ng/mL to more than 2000 ng/mL and correlated significantly with response and event-free survival.29 A similar relation between IM plasma level and response was found in an independent study of 68 patients, in which the data suggested that the trough plasma IM level threshold for MMolR could be set at 1002 ng/mL.30 These data are not surprising, because the therapeutic effects of IM depend on the concentration of the drug in the milieu and in the target cells, which in turn are affected by the factors governing intestinal absorption and liver metabolism,27,28 and by the molecular mechanisms affecting the transport of the drug in and out of leukemic cells.29-36

The IM concentration that inhibits 50% of BCR-ABL enzymatic activity and 50% of BCR-ABL+ cell in vitro growth (IC50) ranges between 500 and 1000 ng/mL and can be easily reached in vivo with a single 400-mg daily dose.25-30 Because inhibition is concentration dependent, a higher IM concentration may be required to inhibit completely BCR-ABL and to optimize therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, during IM treatment several BCR-ABL kinase domain point mutations can develop, conferring resistance to standard-dose IM, but some of them are still sensitive to IM, in vitro, at concentrations below or around 1500 ng/mL.37-41

When this study was planned, the results of the IRIS trial had already been published, confirming the therapeutic efficacy of 400 mg daily,3 and other studies had already reported that a higher IM dose could improve or increase the response.7-9 A single-arm study of 112 patients who were treated front-line with IM 800 mg daily reported a CCgR rate of 90% that compared favorably with the CCgR rate of 74% that was reported for 49 patients treated front-line with 400 mg daily at the same institution.10 More recently, the results of a prospective, single-arm study of 103 patients who were assigned to receive a dose of 600 mg front-line, with dose escalation to 800 mg in case of suboptimal response, were published, reporting a 12-month CCgR and MMolR rate of 88% and 47%, respectively.42 Another prospective, yet single-arm, study of patients with Sokal intermediate risk who were treated front-line with IM 800 mg daily reported a 12-month CCgR of 88% and a MMolR rate of 56%.43 Although these studies were of single-arm design, this trial was designed to compare 800 and 400 mg in a prospective, intention-to-treat, randomized fashion. The CCgR at 12 months was chosen as primary end point, because it was, and still is, the best surrogate marker of later outcome.2,3,6,10,44-46 The results were calculated on all randomly assigned patients, using the intention-to-treat principle. The interpretation of these results is straightforward, because no significant difference could be detected between the experimental arm and the standard arm, for the primary end point, as well as for any other measure of efficacy, toxicity, and compliance (Tables 3,4; Figures 1,Figure 2,Figure 3–4). Some reasons can be discussed. First, detecting or not detecting a difference in cytogenetic and molecular response may depend on methodologic issues.14,19-22,47,48 However, different methods could account for differences between this study and other studies, whereas in this study all cytogenetic and molecular tests were performed in the same laboratories and at the same time, for patients in both arms. Second, this study focused exclusively on Sokal HR patients, who account for approximately 25% of patients with CML, whereas all prior single-arm studies enrolled more low- and intermediate-risk patients than HR patients. Moreover, the boundaries between high-risk and AP are not always sharp, also because the definition of AP may vary.6 On the basis of platelet count and blast cell percentage, 7 of our patients could have been classified in AP, but if these patients were not counted, the CCgR rate at 12 months would have been the same, 64% in the high-dose arm and 59% in the standard-dose arm. Third, we could not show a difference because the sample size was determined to detect an absolute difference of 20% between the expected CCgR rate in the standard-dose arm, which was set at 50% based on the IRIS study13 but was actually slightly higher (58%), and the predicted CCgR rate in the high-dose arm, which was arbitrarily set at 70% but was actually slightly lower (64%). Fourth, although almost all the patients who were assigned to 400 mg could take the full dose, or at least more than 350 mg, many patients who were assigned to 800 mg required a substantial dose decrease (Table 4). Although no subgroup analysis by dose was planned, it cannot be overlooked that the 12-month CCgR rate of the patients who could take the full 800-mg dose, or a dose of 700 to 799 mg, was high (96% and 86%, respectively). However, it is important to notice that in both arms the patients who received less than 350 mg failed almost completely to respond. Fifth, although the number of dropouts and the number of patients who went off treatment for AE and SAE was not significantly different in the 2 arms, it was slightly higher in the high-dose arm (18% or 16.6% vs 10% or 9.2%; P = .156). If these patients were not included in the calculation, so violating the intention-to-treat principle, the 12-month CCgR rate would have become 69 (77%) of 90 patients in the high-dose arm versus 63 (64%) of 98 patients in the standard-dose arm (P = .09).

The results of this study were reported for the first time at the 13th Congress of the European Haematology Association, June 2008.49 At the same Congress, 2 other prospective, controlled, randomized studies of IM 400 mg versus 800 mg were presented. One was a spontaneous study of 400 mg versus 800 mg in 227 patients in late chronic phase who were resistant or intolerant to IFNα, reporting a higher CCgR rate at 6 months but not at 12 months, with 800 mg.50 The other was a company-sponsored study of 476 patients, any risk, who were assigned front-line to receive 800 mg or 400 mg.51 In that study, the end point was the MMolR rate at 12 months, that appeared somewhat higher, but nonsignificantly, in the 800-mg arm.

It is acknowledged that the Sokal prognostic classification, while still providing the most important baseline prognostic factor, may be coming of age and will be modified or replaced, based on the biologic characteristics of leukemia. The reasons why high-risk patients are less responsive to any therapy, with the possible exception of allogeneic stem cell transplantation, are not clear. We hypothesize that the age, the involvement of the megakaryocytic lineage, the higher blast cell proportion, and the greater burden of extramedullary hemopoiesis may all be a cause or a consequence of a greater genomic instability. However, there are no reports of a significant association of Sokal risk with the gene expression profile of leukemic cells or other candidate prognostic factors. It is also acknowledged that the primary end point of this study was the CCgR rate at 12 months, which is a potent and recognized early surrogate marker of survival, but it is only a surrogate. Other prospective studies were designed, and are on the way, to test the effect of IM initial dose on survival.51-53 The concept of IM dose optimization is complex, and probably it cannot be pursued, or applied, in all patients irrespective of response, tolerance, and also pharmacokinetic data. Future improvements may lie in identifying subgroups that could benefit from dose escalation or other agents. However, on the basis of this controlled study, the standard initial or front-line dose of IM for patients with Sokal HR Ph+ CML should be 400 mg once daily. Although the projected 36 months OS was of note (84% in the standard-dose arm and 91% in the high-dose arm), the EFS, which provides a measure of the proportion of patients who are still on therapy and have not failed, was 66% and 62%, respectively, suggesting that HR patients are still in need of improved therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katia Vecchi for collecting the data of the Italian patients, Karin Olsson for collecting the data of the Nordic patients, and Antonio de Vivo, MD, for supervising all informatic issues; their skilled and unevaluable help is strongly acknowledged.

The study was supported by grants from The Italian Association Against Leukemia-Lymphoma and Myeloma (BolognAIL), The Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna, The Italian Ministry of Education (PRIN 2005, no. 20050 63732_003, and PRIN 2007, no. 2007F7 AE7B_002), The University of Bologna, and The European Union (European LeukemiaNet).

Authorship

Contribution: M.B. contributed to writing the protocol, acted as principal investigator, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; G.R. contributed to writing the protocol, acted as responsible investigator for the GIMEMA CML WP, collected and analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript before submission; F.C., I.H., K.P., E.A., G.A., H.E., H.H.-H., L.L., J.L.N., F. Palandri, F. Palmieri, G.R.-C., D.R., G. Specchia, and B.S. contributed by supporting the protocol finalization, collecting and analyzing the data, and revising the manuscript before submission; and V.K., G.M., A.N., U.O., F. Pane, N.T., O.W.-B., and G. Saglio contributed by supporting the protocol finalization, collecting and analyzing the samples for molecular evaluation, and revising the manuscript before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.B. has received research grants from Novartis and has received honorarium as part of speakers' bureau and for consultancy work with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. E.A. has received honorarium as part of speakers' bureau and for consultancy work with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A list of the institutions and investigators who contributed to the study appears in Document S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article.

Correspondence: Michele Baccarani, Institute of Hematology “L. and A. Seràgnoli,” S Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, Via Massarenti, 9, 40138 Bologna, Italy; e-mail: michele.baccarani@unibo.it.