Abstract

The presence of tumor-specific microRNAs reflects tissue of origin and tumor stage. We show that the absence of miRNAs likewise can be used to determine tumor origin (miR-155) and proliferation state because tumor suppressor miRNAs (miR-222/221, let-7 family) were significantly down-regulated in primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and in Kaposi sarcoma (KS), an endothelial cell tumor. PEL and KS are associated with KS-associated herpesvirus infection. We identified 15 virally regulated miRNAs in latently infected, nontumorigenic endothelial cells. MiR-143/145 were elevated only in KS tumors, not virally infected endothelial cells. Thus, they represent tumor-specific, rather than virus-specific, miRNAs. Because many tumor suppressor proteins are wild-type in KS and PEL, down-regulation of multiple tumor suppressor miRNAs provides a novel, alternative mechanism of transformation.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a new class of genes that function as inhibitory RNA molecules that confer specificity to the RNA-induced silencing complex, which degrades the target mRNAs or inhibits protein translation. Because the biochemical function of miRNAs is to inhibit protein expression, it is not surprising that miRNAs can exhibit tumor suppressor phenotypes

Conversely, miRNAs have also been associated with growth-promoting phenotypes if their targets include tumor suppressor proteins or proteins that are required for cell differentiation. Many miRNAs are strictly cell lineage-associated, whereas others are found in multiple tissues, albeit at different levels.1 Hence, miRNAs, like mRNAs, can be subjected to microarray profiling. Tumor signatures based on miRNA profiles have clinical predictive power, analogous to signatures based on mRNA profiles.2 We have used real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction–based arrays to profile miRNAs in 2 AIDS-defining cancers: primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and Kaposi sarcoma (KS).

PEL is a monoclonal CD138+, postgerminal center non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma.3 PELs express CD71+, CD38+ activation markers and are invariably infected with KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). They can be dually infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). EBV-positive and EBV-negative PEL can be differentiated based on their mRNA transcription pattern4 but do not differ appreciably in culture or in animal models.5,6 KS is also associated with KSHV infection.7 KS is a malignancy of endothelial cells (ECs) and thought to be at the border between infection-induced hyperplasia and clonal neoplasia.

We find many known tumor suppressor miRNAs down-regulated in PEL and KS. These include miR-155, miR-220/221, as well as miR-let7 family members. These miRNAs were more down-regulated in the monoclonal, fully transformed PEL than in KS biopsies or KSHV-infected, nontumorigenic ECs. This reinforces the importance of tumor suppressor miRNAs in oncogenic transformation and underscores their clinical utility for tumor classification.

Methods

PELs are listed in Table S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). KS biopsies were obtained with informed consent obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and used deidentified. Whole tonsil samples were used and obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network. RNA was isolated as per our prior procedures,8 and miRNA levels quantified using a commercial assay according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Data were normalized to U6 RNA and clustered using Arrayminer (Optimal Design, Nivelles, Belgium). Analysis of variance, t test, and analysis of residuals after robust regression9 were conducted in R (www.r-project.org).

Results and discussion

To identify miRNAs that are down-regulated in KSHV-associated cancers, we profiled PELs, normal tonsil tissue, KSHV-infected and uninfected ECs, and, for the first time, primary KS biopsies. We had previously used a smaller collection of PELs to catalog miRNAs that were detectable in all PELs.8 At the time, though, we did not have the statistical power to also identify miRNAs that were specifically down-regulated in PEL compared with controls.

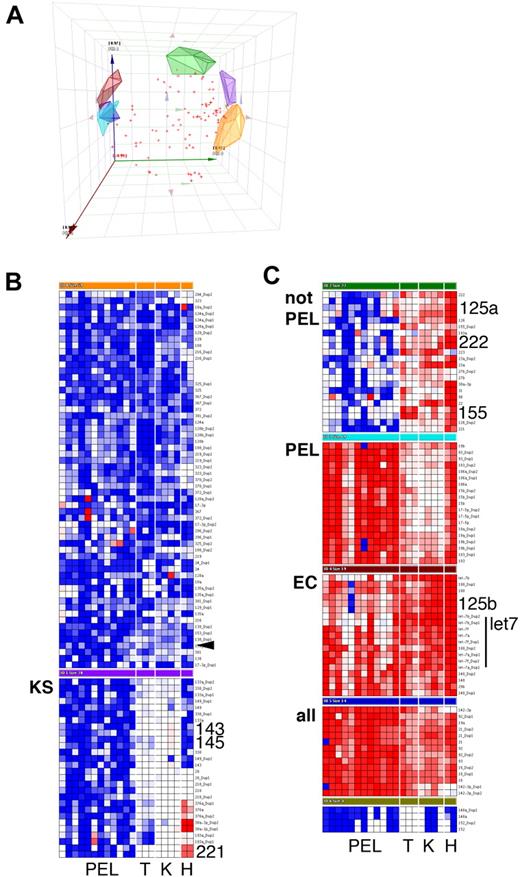

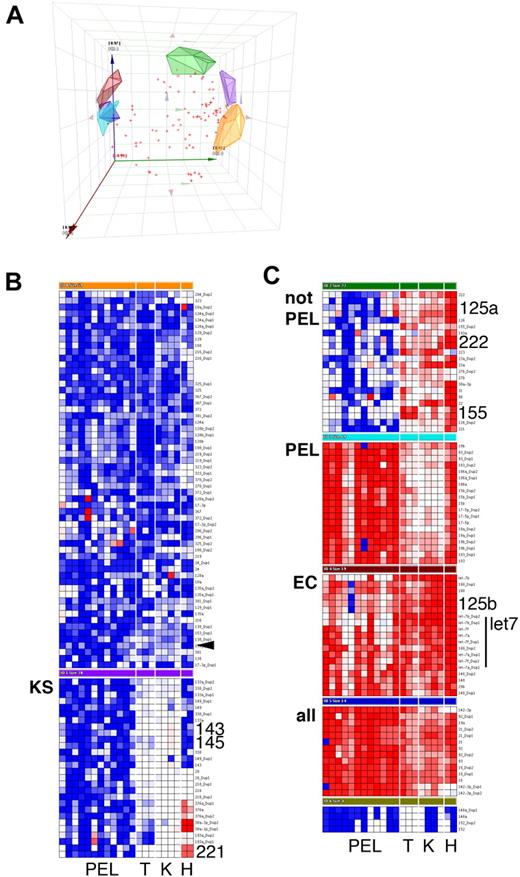

Using a TaqMan real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction-based miRNA array, we determined the levels of 84 mature miRNAs. Based on the large number of samples (n = 21), low false-positive signal of the nontemplate reactions (4.6% of n = 588), and low replicate variability (95% confidence interval of the SD for all individual replicates: 1.63…2.62 CT units), we consider 1.82.62 = 4.7-fold differences in miRNA levels to be biologically significant. All miRNAs were measured in duplicate or triplicate (n = 6265 individual reactions). Principal component analysis identified 7 clusters, as well as miRNAs that could not be uniquely partitioned into any one cluster (Figure 1A). The clusters were (1) miRNAs that were highest in PELs (Figure 1C, cluster PEL); (2) miRNAs that were present at higher levels in KS tumors compared with EC, regardless of KSHV infection, or in PEL, most significantly miR-143 and -145 (Figure 1B, cluster KS; Figure 2A,B); and (3) miRNAs that were down-regulated in PELs compared with tonsil, KS, or ECs (Figure 1C, cluster “not PEL,” “EC”). These included miR-155, which is required for differentiation of germinal center B cells into plasmablasts.10 Low levels of miR-155 are associated with germinal center-type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and genetic instability.11,12 Interestingly, KSHV encodes a viral ortholog to miR-155,13,14 which could compensate for some of the miR-155 functions.

Cluster analysis of mature miRNA levels in KS and PEL. Data were first normalized relative to U6 to yield delta cycle threshold (dCT). dCT data were clustered using a correlation metric. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the data identified 7 clusters as well as miRNAs that did not fall into any of the clusters (red crosses). PCA is a statistical tool of reducing multidimensional datasets. For instance, many miRNA genes are correlated. The PCAs can be derived from gene expression data and form an artificial coordinate system, in which coregulated genes cluster together. (A) Plot of the first 3 PCAs to visually assess the goodness of our cluster algorithm Clean clustering will result in nonoverlapping clusters. (B, C) Heatmap depiction of individual (duplicate) miRNA measurements. Red represents increase relative to all data in this set; blue, decrease relative to all data in this set. Only cluster members are shown, not unclassified miRNAs. PEL indicates primary effusion lymphoma; T, tonsil; K, KS; and H, EC. KS biopsies were from male AIDS-KS patients seen in the United States after 2004. The rightmost lane represents KSHV latently infected ECs. miRNAs that are discussed in the text are in large font.

Cluster analysis of mature miRNA levels in KS and PEL. Data were first normalized relative to U6 to yield delta cycle threshold (dCT). dCT data were clustered using a correlation metric. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the data identified 7 clusters as well as miRNAs that did not fall into any of the clusters (red crosses). PCA is a statistical tool of reducing multidimensional datasets. For instance, many miRNA genes are correlated. The PCAs can be derived from gene expression data and form an artificial coordinate system, in which coregulated genes cluster together. (A) Plot of the first 3 PCAs to visually assess the goodness of our cluster algorithm Clean clustering will result in nonoverlapping clusters. (B, C) Heatmap depiction of individual (duplicate) miRNA measurements. Red represents increase relative to all data in this set; blue, decrease relative to all data in this set. Only cluster members are shown, not unclassified miRNAs. PEL indicates primary effusion lymphoma; T, tonsil; K, KS; and H, EC. KS biopsies were from male AIDS-KS patients seen in the United States after 2004. The rightmost lane represents KSHV latently infected ECs. miRNAs that are discussed in the text are in large font.

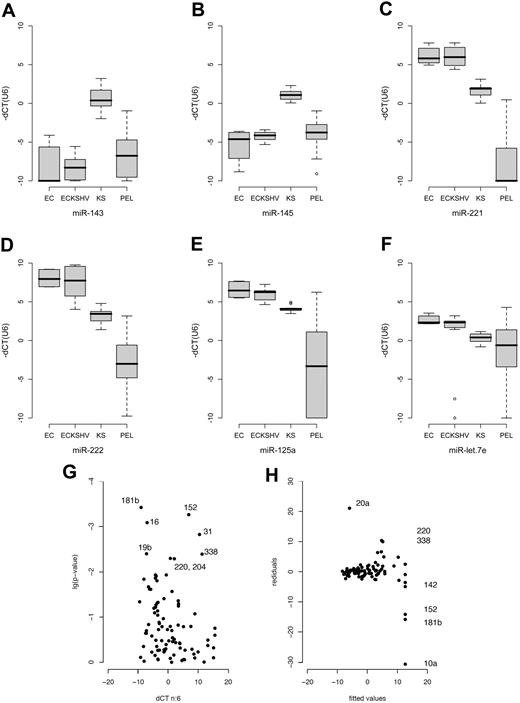

Box plot of miRNA levels in ECs, KSHV-infected ECs, KS, and PEL. Sample classes are shown on the horizontal axis and relative miRNA levels (dCT) on the vertical axis. dCT indicates the miRNA abundance relative to U6 (set to 0). Lower dCT levels correspond to higher mRNA levels on a 2log scale. The line represents the median; boxes, 25% and 75% percentiles; whiskers, 1.5 times the box size. Outliers are indicated by an open circle. (A-F) Based on technical triplicate measurements of each sample and of multiple independent samples for each class. The number of biologic replicates were: ECs, n = 2; EC-KSHV, n = 4; KS, n = 4; PEL, n = 12. Thus, the variation depicted by the box-whisker plot reflects technical as well as biologic variation within each sample class. The P values in each case were less than or equal to .001. (G) Change in miRNA levels in KSHV latently infected ECs. The horizontal axis shows mean relative levels of dCT over n = 6 replicates (3 for uninfected and 3 for KSHV-infected ECs). Lower dCT levels correspond to higher mRNA levels on a log2 scale. The vertical axis shows the P value of the pairwise t test. miRNAs that were significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons25 are labeled. (H) Analysis of residuals for the same dataset. Residuals quantify how far any one actual data point deviates from the fitted prediction based on regression of all data points. Because in array analyses the majority of genes/miRNAs do not change, large residuals identify outliers, that is, those miRNAs that are changed between 2 samples. Analysis of residuals is a more robust and statistically sound technique than calculating the fold change between 2 data points for any one miRNA. Shown on the vertical axis are the residuals and on the horizontal axis the fitted values as predicted by robust linear regression analysis9 of KSHV-infected versus uninfected ECs. Significantly altered genes with residuals greater than 10 units are labeled. Additional changed genes are shown in Table S2.

Box plot of miRNA levels in ECs, KSHV-infected ECs, KS, and PEL. Sample classes are shown on the horizontal axis and relative miRNA levels (dCT) on the vertical axis. dCT indicates the miRNA abundance relative to U6 (set to 0). Lower dCT levels correspond to higher mRNA levels on a 2log scale. The line represents the median; boxes, 25% and 75% percentiles; whiskers, 1.5 times the box size. Outliers are indicated by an open circle. (A-F) Based on technical triplicate measurements of each sample and of multiple independent samples for each class. The number of biologic replicates were: ECs, n = 2; EC-KSHV, n = 4; KS, n = 4; PEL, n = 12. Thus, the variation depicted by the box-whisker plot reflects technical as well as biologic variation within each sample class. The P values in each case were less than or equal to .001. (G) Change in miRNA levels in KSHV latently infected ECs. The horizontal axis shows mean relative levels of dCT over n = 6 replicates (3 for uninfected and 3 for KSHV-infected ECs). Lower dCT levels correspond to higher mRNA levels on a log2 scale. The vertical axis shows the P value of the pairwise t test. miRNAs that were significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons25 are labeled. (H) Analysis of residuals for the same dataset. Residuals quantify how far any one actual data point deviates from the fitted prediction based on regression of all data points. Because in array analyses the majority of genes/miRNAs do not change, large residuals identify outliers, that is, those miRNAs that are changed between 2 samples. Analysis of residuals is a more robust and statistically sound technique than calculating the fold change between 2 data points for any one miRNA. Shown on the vertical axis are the residuals and on the horizontal axis the fitted values as predicted by robust linear regression analysis9 of KSHV-infected versus uninfected ECs. Significantly altered genes with residuals greater than 10 units are labeled. Additional changed genes are shown in Table S2.

MiR-221 and miR-222 were down-regulated in PEL and KS (Figure 1B,C). This was verified by analysis of variance (Figure 2C,D). MiR-221 and miR-222 have multiple phenotypes.15-17 Both miRNAs were also down-regulated in KS compared with KSHV-infected ECs. This unifies earlier observations, which identified c-Kit as a target for miR-221/222 in endothelial cells,18 and observed c-Kit overexpression in KS and KS models.19,20

MiR-125a and let7 family members were also down-regulated in PEL (Figures 1C, 2E,F). These miRNAs are coregulated and exhibit tumor suppressor phenotypes.21,22 In Burkitt lymphoma, ectopic introduction of let-7 family miRNAs decreased c-Myc expression and inhibited cell proliferation.23

To test the hypothesis that KSHV alone was responsible for the alterations in miRNA expression, we used a pair of KSHV-infected or uninfected isogenic EC lines.24 The ECs were immortalized with telomerase and subsequently infected with KSHV.24 After clonal selection, they only express the viral latent proteins and miRNAs. KSHV-infected ECs displayed increased angiogenic potential and enhanced survival in low serum while maintaining EC differentiation markers. They did not form tumors in nude mice and have no detectable chromosome rearrangements (L.W., B.D., D.P.D., unpublished data). Thus, they primarily reflect changes resulting from latent viral infection, rather than secondary alterations resulting from transforming mutations of the host as found in tumorigenic cell lines. We used the t test to identify KSHV-induced miRNAs in these cells (Figure 2G). After adjustment for multiple comparisons25 (q ≤ 0.05), we identified 18 (21%) KSHV-regulated miRNAs. These included miR-31, -16, -19b, -220, -338, -204, -10b, -126, -106a, -15a, and -20a. MiR-181b was not detectable at all in KSHV-negative ECs; miR-20a, -338, and -220 were not present in KSHV-positive ECs. Next in rank order, just above the q ≤ 0.05 significance threshold were miR-376a, -92, -let-7f, and -19a (Table S2).

Because we expected the majority of miRNAs not to change, we used analysis of residuals as an alternative to detect virally regulated miRNAs. This identified miR-181b, -220, -338, -20a, -152, and -10a (Figure 2H). The miRNAs 152 and 10a were not identified by t test because the SD for one of the triplicate measurements was more than 1 CT unit. In case of miR-10a, the entire sample was variable. By contrast, we identified a single reaction failure as an outlier in case of miR-152. As such, miR-152 is also KSHV regulated. There is a caveat in pairwise comparisons as opposed to multisample cluster analysis (Figure 1), as these comparisons are sensitive to clonal variation. Figure S1 shows the degree of variations for the technical and biologic replicates.

To establish the biologic relevance of the KSHV-regulated miRNAs, we analyzed their levels in immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (2 isolates), KSHV-infected immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (4 clones, including the KSHV-infected tumorigenic E1, L1 cell lines), KS and PELs by analysis of variance. KSHV-induced miRNAs were elevated in KS biopsies and many were higher in PEL still (Figure 2A-F). This pattern correlated with KSHV latent mRNA and miRNA levels, which are higher in KS tumors compared with KSHV-infected ECs, and highest in PELs.8

In conclusion, we report that multiple tumor suppressor miRNAs (miR-155, miR-220/221, let-7 family) are down-regulated in KSHV-associated cancers, including PEL and KS. This is also the first report of miRNA profiling of primary KS biopsies. We identified miR-143/145 as novel KS tumor-regulated, as opposed to KSHV-regulated, miRNA biomarkers. Because the classic tumor suppressor proteins (p53, Rb, p21/ARF, PTEN) are not mutant in KSHV-associated malignancies6 (and D.P.D., unpublished data), the down-regulation of tumor suppressor miRNAs provides an alternative mechanism of transformation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize for omitting many excellent publications on individual miRNA targets because of page restrictions.

This work was supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Foundation (6021), the University Cancer Research Fund (Chapel Hill, NC), the AIDS Malignancies Clinical Trials Consortium (CA121947), and the National Institutes of Health (CA109232, DE018304, CA096500, CA121935, and HL083469). B.D. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Foundation scholar. A.J.O. was supported by National Institutes of Health training Grant T32 AI00741.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.O. performed research, wrote the paper, and analyzed data; L.W. performed research; B.J.D. and W.J.H. contributed vital new reagents; B.D. designed research; and D.P.D. designed research, wrote the paper, and analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dirk P. Dittmer, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, 715 Mary Ellen Jones CB#7290, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7290; e-mail: ddittmer@med.unc.edu.