Abstract

Rigorously defined reconstitution assays developed in recent years have allowed recognition of the delicate relationship that exists between hematopoietic stem cells and their niches. This balance ensures that hematopoiesis occurs in the marrow under steady-state conditions. However, during development, recovery from hematopoietic stress and in myeloproliferative disorders, hematopoiesis occurs in extramedullary sites whose microenvironments are still poorly defined. The hypomorphic Gata1low mutation deletes the regulatory sequences of the gene necessary for its expression in hematopoietic cells generated in the marrow. By analyzing the mechanism that rescues hematopoiesis in mice carrying this mutation, we provide evidence that extramedullary microenvironments sustain maturation of stem cells that would be otherwise incapable of maturing in the marrow.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells reside in the marrow where they are guided by specific microenvironmental cues and growth factors to generate all the cellular elements of the blood.1 In recent years, the development of rigorous stem cell assays and of molecular tools for single-cell analyses has permitted characterization of the delicate relationship established by stem cells with their microenvironment as they mature in the marrow.2-4 However, under certain circumstances (fetal development, recovery from stress, and myeloproliferative disorders) hematopoiesis does not occur in the marrow but in extramedullary sites. The relationship established by the stem cells with the microenvironment in these extramedullary sites is still poorly understood.

Gata1 is a member of the GATA family of transcription factors indispensable for appropriate maturation of hematopoietic cells of many lineages, including erythroid cells and megakaryocytes (MKs).5 In both mice and humans, the Gata1 locus has a complex organization spanning approximately 10 Kb of the X chromosome.6 This genomic framework ensures that the gene is appropriately transcribed in hematopoietic cells of different lineages.7-11 The hypomorphic Gata1low mutation deletes those regulatory sequences of the gene, including the hypersensitive site 1 (HS1, also known as HS-3.5 and G1H2), that drive expression in erythroid cells and megakaryocytes (MKs).7,8 Because of the reduced Gata1 levels, the mutation induces anemia, due to increased apoptosis of basophilic erythroblasts, and thrombocytopenia, due to increased megakaryocyte (MK) proliferation with delayed maturation.8,12,13 The mutation is lethal in the C57BL/6 strain but is viable in those strains that efficiently recruit the spleen as extramedullary hematopoietic site in response to stress14 (and D. Metcalf, personal e-mail communication, March 2, 2008). This important phenotypic difference among strains suggests the existence of gene modifiers that may rescue the hematopoietic defects induced by the Gata1low mutation by improving the supportive role of the splenic microenvironment.14

By analyzing the phenotype of hemizygous Gata1low/0 males and heterozygous Gata1low/+ females after splenectomy, by tracking experiments with a reporter gene under the control of HS2, an alternative Gata1 enhancer not deleted by the hypomorphic mutation, and by transplantation studies of Gata1low/0 bone marrow cells in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, we demonstrate that Gata1low stem cells fail to mature in the marrow but are specifically rescued by an extramedullary microenvironment such as the spleen. This microenvironment is capable to support the maturation of stem/progenitor cells with an alternative chromatin configuration of the Gata1 locus that enables their progeny to express Gata1 from regulatory regions spared by the hypomorphic mutation. These results provide evidence for the existence of organ-specific microenvironments capable of sustaining maturation of epigenomically alternative stem cells.

Methods

Mice

Gata1low/0 males, heterozygous Gata1low/+ females, and wild-type males obtained by crossing fifth-generation Gata1low/0 males14 with CD1 females (Charles River) and heterozygous Gata1low/+ DBA/2NCrBR females were used in the study. −2.7kbGata1GFP mice were provided by Dr D. Scadden and −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 and −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 males were obtained by standard genetic methods.15 The mice were housed under conditions of good animal care practices and the experimental protocols approved by the institutional animal care committee of the Instituto Superiore Sanità.

Splenectomy

Mice were anaesthetized with xylazine (10 mg/kg; Bayer) and ketamine (200 mg/kg; Gellini Farmaceutics) and the spleen was removed after double ligation of the splenic artery and vein. The muscle, peritoneum, and skin were closed in separate layers using sterile 5-0 absorbable suture. Animals received the analgesic butorphanol subcutaneously (5 mg/kg per day; intervet Italia Srl) for 4 days after surgery (see supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table 1 for further details, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Transplantation studies

NOD/SCID females (6-8 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River and were kept in microinsulator cages in laminar flow racks. The animals were housed in the animal facility for at least 1 week before beginning the experiments. NOD/SCID mice were treated with total body irradiation (3.5 Gy) 4 to 24 hours before tail vein injection of 106 bone marrow cells from Gata1low/0 males.16 Two to 4 months from the transplantation, the mice were killed and blood cells, bone marrow, spleen, and liver were collected. The frequency of donor-derived cells in the various tissues was evaluated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotype at the Gata1 locus7 and by quantitative PCR based on the amplification ratio between X chromosome– and Y chromosome–specific sequences.17

Hematologic parameters

Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus into ethylen-diamino-tetracetic acid–coated microcapillary tubes (20-40 μL/sampling). Hematocrit, platelet, and white blood cell counts were determined manually.

Histology

Femurs, tibias, and liver sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Gomory-silver (MicroStain MicroKit; Diapath), or Mallory-trichromic staining.18,19 For immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated either with anti-Gata1 or anti-CD45 monoclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), stained with an avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase system (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories), and counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin. Alternatively, slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and consecutively incubated with a rabbit anti-cKit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a FITC anti–rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), a goat anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (RocklandInc), and a TRITC anti–goat secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories; all incubations were 1 hour long at 37°C), as described.20 Histologic observations were carried out using a ZEISS AXIOSKOPE light microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Coolsnap Videocamera (Roper Scientific Photometrics) and the acquired images were analyzed with the MetaMorph 6.1 Software (Universal Imaging Corp).

Flow cytometry and cell purification

Cells were first incubated with a Fcγ blocker (CD16/CD32) and then stained with phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated CD117 (anti-cKit), CD71, and CD61 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD34, TER119, and CD41 (all from PharMingen). The cells in the prospective stem/progenitor cell (cKit+/CD34+ or CD34−), erythroblast (CD71+/TER+), and megakaryocytic (CD41+/CD61+) gates were isolated by sorting with an ARIA cell sorter (Becton Dickinson) and shown to be more than 90% pure based upon reanalysis.21

Progenitor cell counts

Marrow (2 × 104 cells/mL), blood (2 μL/mL), and liver (105 cells/mL) cells or purified stem/progenitor cells (100 cells/mL) were cultured in methylcellulose (0.9% wt/vol) containing fetal bovine serum (30% vol/vol), rat stem cell factor (100 ng/mL), mouse interleukin-3 (10 ng/mL; all from Sigma-Aldrich), and human erythropoietin (EPO, 2 U/mL; Boehringer Mannheim). The culture dishes were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in air. Colonies were scored either after 8 or 15 days of culture, as indicated. In selected experiments, single erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E)–derived colonies were plucked manually from the methylcellulose for gene expression analyses.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared by lysing single erythroid colonies or prospectively isolated cell populations into Trizol (Gibco BRL). RNA was reverse transcribed with 2.5 μM random hexamers using the superscript kit (Invitrogen) and gene expression levels were quantified by real-time reverse-transcription PCR, as described.21 GAPDH cDNA was amplified as an internal standard. Reactions were performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Cycle threshold (Ct) was calculated with the SDS software Version 1.3.1 (Applied Biosystems) and expression levels were expressed as 2−ΔCt (ΔCt = target gene Ct − GAPDH Ct).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance (Anova test) using Origin 3.5 software for Windows (Microcal Software Inc) or by Kruskal-Wallis and Bonferroni-Dunn posthoc and Mann-Whitney tests using GraphPad Prism 4.0, as appropriate.

Results

Splenectomized Gata1low/0 males die of anemia

To study the role of the spleen in rescuing the hematopoietic defects induced by the Gata1low mutation, splenectomy was performed in hemizygous Gata1low/0 males and in heterozygous Gata1low/+ females. A dramatic sex-related difference was observed in long-term survival (supplemental Table 1). Although only a few wild-type (3/11) and heterozygous (1/20) females died during the first month after surgery, all the hemizygous males (9/9) died of severe anemia (hematocrit, .066 ± .012 [6.6% ± 1.2%]) within 1 month after surgery, suggesting that hemizygous females were rescued by the presence of the normal allele.

Marrow hematopoiesis in splenectomized Gata1low/+ females is predominantly wild type

Because Gata1 is localized on the X chromosome,6 all hematopoietic cells in Gata1low/0 males express the mutant allele, whereas those from Gata1low/+ females may express either the Gata1low or the wild-type allele, depending on which copy is inactivated during the lyonization process in embryogenesis. If the expression of either one of the 2 alleles does not confer a proliferative advantage, the ratio between the 2 progenitor cell populations in the marrow of Gata1low/+ females should be 50:50. The observations that hemizygous Gata1low/0 male mice died of severe anemia after splenectomy indicated a permissive role for the spleen microenvironment allowing amplification and maturation of Gata1low progenitor cells. Therefore, removal of the spleen might even favor amplification of wild-type progenitor cells in the marrow of the Gata1low/+ females. To test this hypothesis, the frequency of erythroid progenitors expressing the wild-type and the Gata1low allele in the marrow of untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ females was compared.

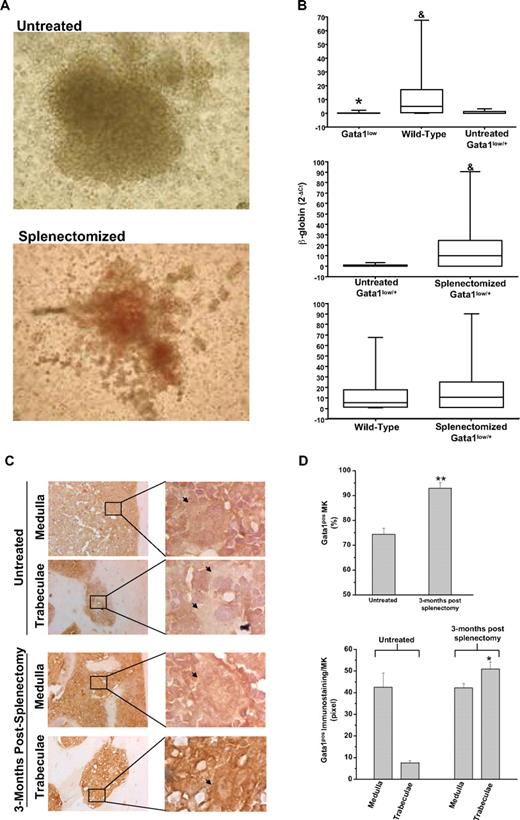

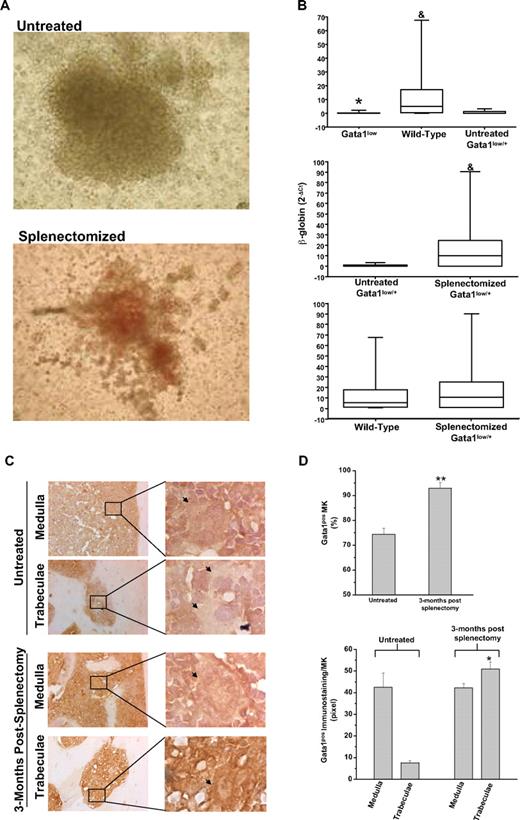

The numbers of BFU-E–derived colonies assayed from the marrow of untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ females were similar (> 150/2 × 104 cells). The BFU-E–derived colonies from the marrow of splenectomized Gata1low/+ females, however, contained greater numbers of cells. Furthermore, the cells were noticeably more mature (as judged by the intensity of their red color, which is indicative of the hemoglobin content) than those derived from untreated Gata1low/+ females (Figure 1A). Erythroid colonies derived from wild-type and Gata1low mice were distinguished on the basis of the levels of β-globin expression (Figure 1B). As expected,7 the levels of β-globin expressed by single colonies assayed from untreated Gata1low/0 males and Gata1low/+ females were significantly lower than those expressed by cells from untreated wild-type mice. By contrast, the levels of β-globin expressed by colonies assayed from splenectomized Gata1low/+ females and wild-type mice were statistically higher than those expressed by the colonies from untreated Gata1low/+ females and similar to those expressed by colonies from wild-type animals (Figure 1B and supplemental Table 2). Therefore, the majority of the erythroid colonies from the marrow of splenectomized Gata1low/+ females were derived from progenitor cells expressing the wild-type allele. A precise quantification of the ratio between colonies (of all type) derived from wild-type and Gata1low progenitor cells in the marrow of the splenectomized Gata1low/+ females will require, however, a formal clonal analyses for the expression of polymorphic genes sufficiently close to the Gata1 gene to cosegregate with this gene during meiosis.

The erythroid progenitors and the MKs present in the marrow of splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice are predominantly derived from the stem cell population expressing the wild-type Gata1 allele. (A) Photograph of a representative erythroid colony generated from the marrow of untreated and splenectomized 18-month-old Gatalow/+ female littermates. Magnification: ×10. (B) Statistical analyses of the levels of β-globin expressed by single erythroid colonies generated in marrow cultures of untreated wild-type, Gata1low/0, and Gata1low/+ mice (top panel) or from untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ littermates (middle panel) or from wild-type and splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice (bottom panel). Results are expressed as median (the line across the boxes), 25% to 75% interquartile range (the boxes), and maximal and minimal value (the end of the vertical line across the boxes). Differences in expression levels were compared by Kruskal-Wallis and Bonferroni-Dunn posthoc tests (top panel) or by Mann Whitney test (middle and bottom panels). * and & indicate levels of β-globin significantly lower (P < .001) than those expressed by cells from wild-type and untreated Gata1low/+ females, respectively (see supplemental Table 1 for further details). (C) Gata1 immunostaining of bone sections of untreated Gata1low/+ mice (top panels) and mice 3 months after splenectomy (bottom panels). All the mice were 9 to 10 months old. Because, to avoid interference with the immunostaining (in brown), the slides were not counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin, MKs are indicated by arrows for clarity. Magnification: ×20. Representative areas (indicated by rectangles) corresponding to the medulla and the bone trabeculae are also represented at ×100 magnification. Similar results were observed with 3 additional untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice. (D) Frequency of Gata1pos MKs (top panel) and level of Gata1 staining in single Gata1pos MKs (bottom panel) from untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ females. Results are presented as mean (± SD) determinations with 3 mice per experimental group. The frequency of Gata1pos cells was determined by analyzing at ×40 magnification 100 MKs for each mouse. The level of Gata1 immunostaining in Gata1pos MKs was determined on 5 MKs randomly chosen in the medullar or in the trabecular area of the bone for each animal with the MetaMorph 6.1 program. Values statistically different (P < .05 or P < .001) from those observed in untreated mice are indicated by * and **, respectively.

The erythroid progenitors and the MKs present in the marrow of splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice are predominantly derived from the stem cell population expressing the wild-type Gata1 allele. (A) Photograph of a representative erythroid colony generated from the marrow of untreated and splenectomized 18-month-old Gatalow/+ female littermates. Magnification: ×10. (B) Statistical analyses of the levels of β-globin expressed by single erythroid colonies generated in marrow cultures of untreated wild-type, Gata1low/0, and Gata1low/+ mice (top panel) or from untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ littermates (middle panel) or from wild-type and splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice (bottom panel). Results are expressed as median (the line across the boxes), 25% to 75% interquartile range (the boxes), and maximal and minimal value (the end of the vertical line across the boxes). Differences in expression levels were compared by Kruskal-Wallis and Bonferroni-Dunn posthoc tests (top panel) or by Mann Whitney test (middle and bottom panels). * and & indicate levels of β-globin significantly lower (P < .001) than those expressed by cells from wild-type and untreated Gata1low/+ females, respectively (see supplemental Table 1 for further details). (C) Gata1 immunostaining of bone sections of untreated Gata1low/+ mice (top panels) and mice 3 months after splenectomy (bottom panels). All the mice were 9 to 10 months old. Because, to avoid interference with the immunostaining (in brown), the slides were not counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin, MKs are indicated by arrows for clarity. Magnification: ×20. Representative areas (indicated by rectangles) corresponding to the medulla and the bone trabeculae are also represented at ×100 magnification. Similar results were observed with 3 additional untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice. (D) Frequency of Gata1pos MKs (top panel) and level of Gata1 staining in single Gata1pos MKs (bottom panel) from untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ females. Results are presented as mean (± SD) determinations with 3 mice per experimental group. The frequency of Gata1pos cells was determined by analyzing at ×40 magnification 100 MKs for each mouse. The level of Gata1 immunostaining in Gata1pos MKs was determined on 5 MKs randomly chosen in the medullar or in the trabecular area of the bone for each animal with the MetaMorph 6.1 program. Values statistically different (P < .05 or P < .001) from those observed in untreated mice are indicated by * and **, respectively.

These results suggest the preferential outgrowth of cells with an activated wild-type allele in the marrow of splenectomized Gata1low/+ females.

To confirm that wild-type progenitor cells became the prevalent population in the marrow of heterozygous Gata1low/+ females after splenectomy, expression of Gata1 by MKs present in the marrow of splenectomized animals was analyzed (Figure 1C-D). Both Gata1neg and Gata1pos MKs were present in the marrow of untreated Gata1low/+ females, whereas MKs detectable in sections of splenectomized Gata1low/+ females were primarily Gata1pos (Figure 1C-D). In addition, the frequency of MKs in the marrow of the splenectomized females progressively decreased to that observed in wild-type controls of comparable age (11 ± 1 vs 26 ± 6/mm2 in splenectomized and untreated 15- to 18-month-old Gata1low/+ mice [P < .01] and 11 ± 1/mm2 in wild-type littermates). Furthermore, blood platelet counts significantly increased (by 2- to 3-fold) after splenectomy to values similar to those observed in age-matched wild-type controls (0.42 ± 0.14 vs 0.1 ± 0.05 × 106/mL in splenectomized and untreated 15- to 18-month-old Gata1low/+ mice [P < .01] and 0.73 ± 0.14 × 106/mL in wild-type littermates, supplemental Figure 2).

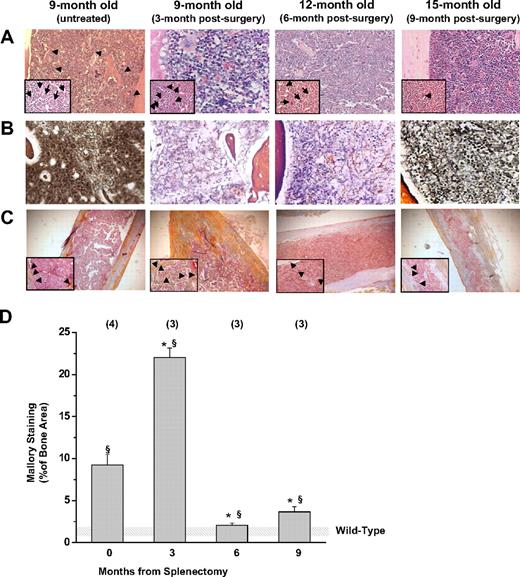

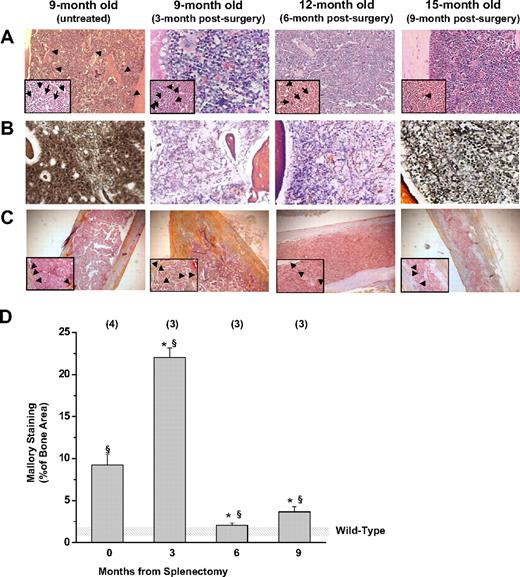

Marrow fibrosis12 and new bone formation22,23 represent characteristic pleiotropic traits of old Gata1low mutants and are thought to be secondary events triggered by MKs abnormalities. The observed prevalence of Gata1pos MKs in the marrow of Gata1low/+ females after splenectomy suggested that splenectomy might also reduce fibrosis and bone formation. Indeed, bone marrow cell counts and hematoxylin-eosin staining of bone marrow sections (Figure 2A) confirmed that the cellularity of the marrow of splenectomized Gata1low/+ females remained normal with age (8 ± 1 vs 3 ± 1 × 106/femur in splenectomized and untreated 15- to 18-month-old Gata1low/+ mice [P < .01] and 10 ± 2 × 106/femur in wild-type littermates, supplemental Figure 2). Although marrow fibrosis was still detected in splenectomized Gata1low/+ females, its extent was greatly reduced compared with that observed in nonsplenectomized mutant mice of similar age (Figure 2B). Moreover, the areas of active bone formation, as indicated by Mallory staining,18 increased 3 months after splenectomy, but became undetectable by 6 to 9 months (Figure 2C-D).

Splenectomy reduces the development of marrow fibrosis and new bone formation in Gata1low/+ mice. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin, (B) Gomory-silver, and (C) Mallory staining of long bones from Gata1low/+ females at different time points after splenectomy, as indicated. Results are compared with those of untreated Gata1low/+ female littermates at 9 months of age. Results are representative of those obtained in multiple experiments. Representative MKs and bony trabeculae are indicated by arrows and arrowheads in the insets, respectively. Magnification is ×20 in the panels and ×40 in the insets. (D) Levels of Mallory staining of the femur of untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice. Results are presented as mean ± SD determinations of at least 3 mice per experimental group and are compared with those observed in untreated wild-type mice of comparable age (shaded area). The levels of Mallory staining were determined by analyzing with the MetaMorph program at least 3 randomly chosen bone areas per mouse. Values statistically different (P < .05 and P < .01) from those observed in untreated wild-type and Gata1low/+ females are indicated by § and *, respectively.

Splenectomy reduces the development of marrow fibrosis and new bone formation in Gata1low/+ mice. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin, (B) Gomory-silver, and (C) Mallory staining of long bones from Gata1low/+ females at different time points after splenectomy, as indicated. Results are compared with those of untreated Gata1low/+ female littermates at 9 months of age. Results are representative of those obtained in multiple experiments. Representative MKs and bony trabeculae are indicated by arrows and arrowheads in the insets, respectively. Magnification is ×20 in the panels and ×40 in the insets. (D) Levels of Mallory staining of the femur of untreated and splenectomized Gata1low/+ mice. Results are presented as mean ± SD determinations of at least 3 mice per experimental group and are compared with those observed in untreated wild-type mice of comparable age (shaded area). The levels of Mallory staining were determined by analyzing with the MetaMorph program at least 3 randomly chosen bone areas per mouse. Values statistically different (P < .05 and P < .01) from those observed in untreated wild-type and Gata1low/+ females are indicated by § and *, respectively.

These results indicated that, in the absence of the spleen, the stem/progenitor cells expressing the wild-type allele contributed prevalently to hematopoiesis in the marrow of Gata1low/+ females, preventing or reducing progression of fibrosis and bone formation with age.

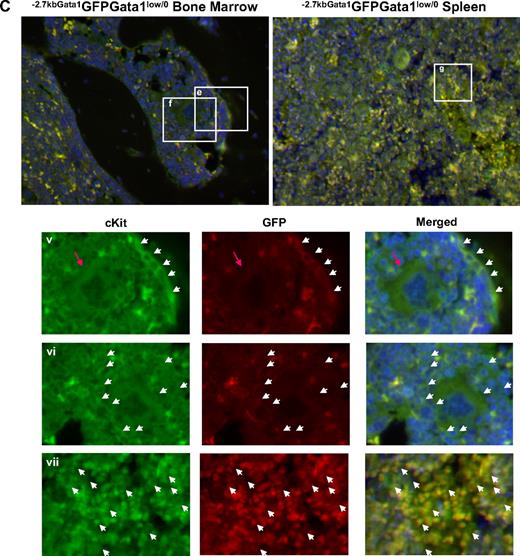

Gata1low/0 progenitor cells are associated with the endosteum in the marrow and the vascular niche in the spleen

Gata1lowcKitpos cells do not express CXCR4,24 the receptor for SDF1, that allows hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to interact with the vascular niche in the marrow.2-4 This observation suggests that the failure of Gata1lowcKitpos cells to mature in the marrow is due to poor interaction with the vascular niche. To test this hypothesis, the location of cKitpos cells within the architecture of the marrow of wild-type (Gata1+/0) and Gata1low (Gata1low/0) mutants was compared by immunohistochemistry (Figure 3). In these experiments, hematopoietic cells were further labeled with a GFP reporter gene under the control of the regulatory regions of Gata1 spared by the Gata1low mutation (−2.7KbGata1GFP) introduced by standard genetic approaches in the genome of Gata1low/0 mice (Figure 3A).

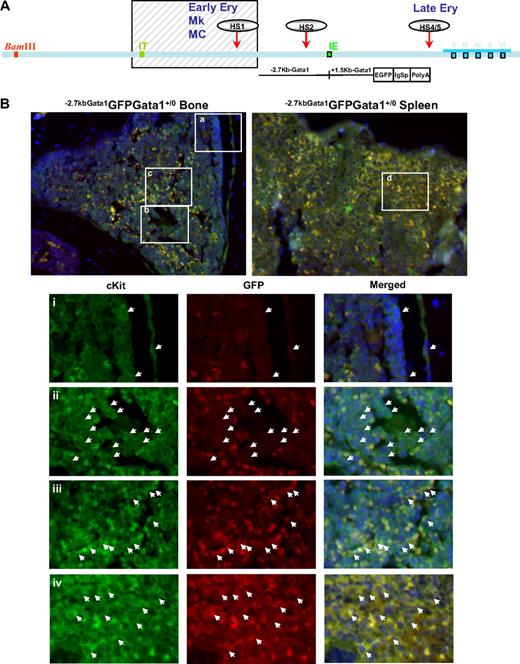

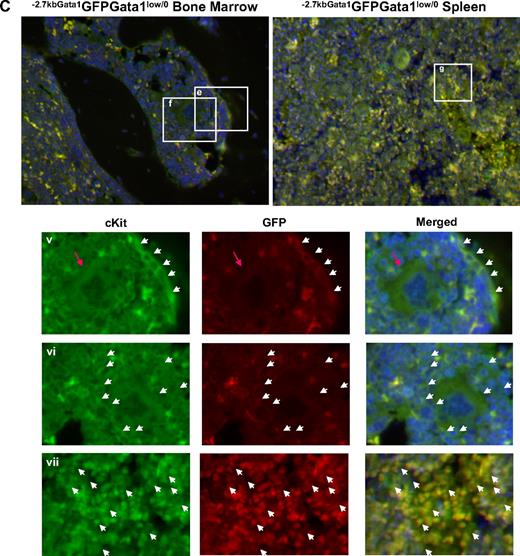

Altered localization of the stem/progenitor cells (cKitpos) within the architecture of the marrow of Gata1low mice. (A) Genomic organization of the murine Gata1 locus indicating the position of the proximal (IE) and distal (IT) promoter and of the HS1 (also known as HS-3.5 and G1HE), the HS2, and the HS4/5 (also known as HS+3.5) enhancer. The shaded box indicates the sequences deleted by the hypomorphic Gata1low mutation. The sequences −2.7 Kb upstream and 1.5 Kb downstream of IE driving the expression of the GFP reporter (−2.7Kb Gata1GFP) are indicated at the bottom (see also Skoda15 and Onodera et al25 ). (B-C) Double cKit and GFP immunofluorescence analysis of marrow and spleen sections of −2.7KbGata1GPFGata1+/0 (B) and −2.7KbGata1GPFGata1low/0 (C) mice, as indicated. The panels on the top present the merged pictures of representative areas of the bone marrow and spleen at ×20 magnification. The rectangles indicate the areas of the sections shown at higher (×40) magnification on the panels in the bottom. These bottom panels present the fluorescent signal of cKit and GFP captured individually and merged. The arrows track the position of individual cKitpos cells in the different panels. The red arrowhead in panel E indicates a GFPneg MK in proximity to the bone endosteum of the Gata1low mouse. Legend: −2.7KbGata1GPFGata1+/0 mouse: (i) 3 cKitposGFPneg cells, one of which is close to the endosteum; (ii) a cluster of cKitposGFPneg cells in the medulla; (iii) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells in the medulla; (iv) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells in the spleen. −2.7Kbgata1GPFGata1low/0 mouse: (v) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells close to the bone endosteum; (vi) a cluster of cKitposGFPneg cells in the medulla; (vii) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells in the spleen.

Altered localization of the stem/progenitor cells (cKitpos) within the architecture of the marrow of Gata1low mice. (A) Genomic organization of the murine Gata1 locus indicating the position of the proximal (IE) and distal (IT) promoter and of the HS1 (also known as HS-3.5 and G1HE), the HS2, and the HS4/5 (also known as HS+3.5) enhancer. The shaded box indicates the sequences deleted by the hypomorphic Gata1low mutation. The sequences −2.7 Kb upstream and 1.5 Kb downstream of IE driving the expression of the GFP reporter (−2.7Kb Gata1GFP) are indicated at the bottom (see also Skoda15 and Onodera et al25 ). (B-C) Double cKit and GFP immunofluorescence analysis of marrow and spleen sections of −2.7KbGata1GPFGata1+/0 (B) and −2.7KbGata1GPFGata1low/0 (C) mice, as indicated. The panels on the top present the merged pictures of representative areas of the bone marrow and spleen at ×20 magnification. The rectangles indicate the areas of the sections shown at higher (×40) magnification on the panels in the bottom. These bottom panels present the fluorescent signal of cKit and GFP captured individually and merged. The arrows track the position of individual cKitpos cells in the different panels. The red arrowhead in panel E indicates a GFPneg MK in proximity to the bone endosteum of the Gata1low mouse. Legend: −2.7KbGata1GPFGata1+/0 mouse: (i) 3 cKitposGFPneg cells, one of which is close to the endosteum; (ii) a cluster of cKitposGFPneg cells in the medulla; (iii) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells in the medulla; (iv) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells in the spleen. −2.7Kbgata1GPFGata1low/0 mouse: (v) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells close to the bone endosteum; (vi) a cluster of cKitposGFPneg cells in the medulla; (vii) a cluster of cKitposGFPpos cells in the spleen.

Along the endosteum of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 controls, very few (< 0.005/μm) cKitpos cells, all of which were GFPneg, were detected, whereas several (1.5 cells/mm2) cKitpos cells, equally distributed in GFPpos or GFPneg clusters, were present within the medulla (Figure 3). These clusters likely correspond, respectively, to islands of erythroid- and myeloid-restricted maturation.26 By contrast, clusters of (0.01/μm) GFPposcKitpos cells were detected along the endosteum and few (< 1 cell/mm2) cKitposGFPneg cells were detectable within the medulla of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 males (Figure 3B). Therefore, GFPposcKitpos cells were below detectable levels in wild-type mice, whereas almost all the cKitpos cells near the endosteum of Gata1low mice were GFPpos. The frequency of cKitpos cells, all of which were GFPpos, in the spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 and Gata1low/0 males was similar (1.4 cells/μm in both cases). However, due to its larger size,14 the spleen of the mutant mice contained an absolute number of cKitpos cells higher (by ∼ 3-fold) than that of the spleen from wild-type animals (the total number of cKitpos cells in the marrow and spleen of Gata1low/0 mice has been calculated to be 5.3 × 106 and 39 × 106 cells, respectively, supplemental Table 3).

These experiments indicated that, although the frequency of cKitpos cells in the marrow of wild-type and Gata1low/0 mice is similar, the distribution of these cells within the marrow of the 2 animals is very different. In Gata1+/0 mice, association of cKitpos cells with the endosteum was rare and the majority of these cells were found instead in the medulla, whereas most of the cKitpos cells in the marrow of Gata1low/0 mice were associated with the endosteum and few of them were found within the medulla. On the other hand, numerous cKitpos cells were found in the medulla of the spleen of Gata1low/0 mice. Therefore, the Gata1low mutation impairs the ability of the stem/progenitor cells to interact with the vascular niche of the marrow but does not affect the ability of these cells to interact with the vascular niche of the spleen.

Gata1low/0 hematopoietic progenitor cells in the spleen exhibit activation of the alternative HS2 enhancer and are functional in colony assay

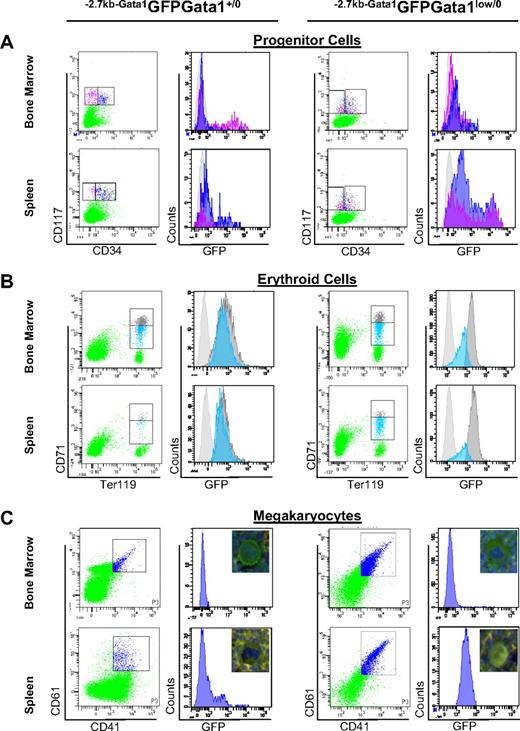

The regulatory regions of the Gata1 gene include 2 promoters and several DNase hypersensitive sites.25,27 Of those, the HS1 enhancer deleted by the Gata1low mutation is a strong enhancer in transfection assays and drives expression of the gene in erythroid, megakaryocytic, and mast cells. The regulatory regions spared by the hypomorphic mutations include a second enhancer, HS2, and a palyndromic GATA motive adjacent to the proximal promoter.25 These sequences have weak enhancer activity in transfection assays and, under steady-state conditions, drive Gata1 expression in eosinophils.9 The observation that the cKitpos clusters found along the endosteum of Gata1low/0 mice expressed high levels of GFP reflected the active status of the alternative HS2 enhancer in these cells, suggesting that Gata1low progenitor cells may have acquired the ability to activate this enhancer. To test this hypothesis, the levels of GFP expressed by hematopoietic cells prospectively isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from the marrow and spleen of −2.7KbGata1GFP wild-type and −2.7KbGata1GFPGata1low/0 mutants were compared (Figure 4 and Table 1). Because the Gata1low mutation disrupts the normal relationship between antigenic profile and function of the stem/progenitor cells,21,29 in these experiments cKitpos stem/progenitor cells were grossly divided into CD34neg (hematopoietic stem cells [HSCs]/common erythroid-megakaryocytic restricted progenitor cells [MEPs]) and CD34pos (common myeloid progenitor cells [CMPs] and granulomonocytic restricted progenitor cells [GMPs]) cells.30

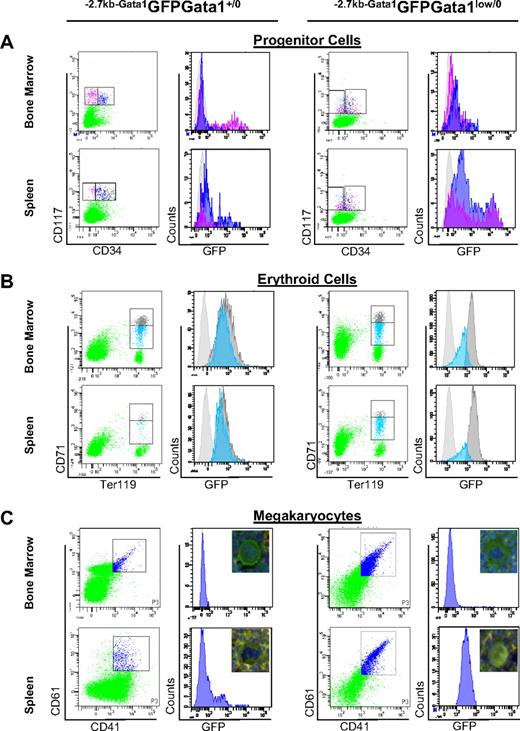

Alternative activation of the Gata1 locus in stem/progenitor cells and erythroid and MK precursors from the spleen of Gata1low mice. (A) Levels of GFP expressed by marrow and spleen stem/progenitor cells divided into stem/common erythroid-megakaryocytic progenitors (pink) and granulomonocytic and common myeloid progenitors (blue) by CD34 staining (CD34neg and CD34pos, respectively). (B) Levels of GFP expressed by marrow and spleen erythroid cells (Ter119pos) divided into immature (CD71high, gray) and mature (CD71med, blue) erythroblasts.28 (C) Levels of GFP expressed by marrow and spleen MKs identified by CD41/CD61 staining. Irrelevant controls for GFP-specific signal are presented as light gray histograms in all of the panels. The pictures (40 × original magnification) of representative MKs double stained for cKit and GFP are included in panel C. The frequency and average GFP fluorescence intensity (AFI) of the different populations is summarized in Table 1. Similar results were obtained in 4 separate experiments.

Alternative activation of the Gata1 locus in stem/progenitor cells and erythroid and MK precursors from the spleen of Gata1low mice. (A) Levels of GFP expressed by marrow and spleen stem/progenitor cells divided into stem/common erythroid-megakaryocytic progenitors (pink) and granulomonocytic and common myeloid progenitors (blue) by CD34 staining (CD34neg and CD34pos, respectively). (B) Levels of GFP expressed by marrow and spleen erythroid cells (Ter119pos) divided into immature (CD71high, gray) and mature (CD71med, blue) erythroblasts.28 (C) Levels of GFP expressed by marrow and spleen MKs identified by CD41/CD61 staining. Irrelevant controls for GFP-specific signal are presented as light gray histograms in all of the panels. The pictures (40 × original magnification) of representative MKs double stained for cKit and GFP are included in panel C. The frequency and average GFP fluorescence intensity (AFI) of the different populations is summarized in Table 1. Similar results were obtained in 4 separate experiments.

In −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 males, 36% to 58% of the cKitposCD34neg cells of the marrow and of the cKitposCD34pos cells of the spleen expressed GFP (Figure 4A and Table 1). By contrast, in −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 males, GFP was expressed by a minority (10%-18%) of the cKitposCD34pos cells of the marrow and by the majority (> 80%, in 12%-20% of these at levels > 10 000 AFI/cell) of the cKitpos (both CD34pos and CD34neg) of the spleen. The greater GFP expression (and thus presumably HS2 activity) in cKitpos cells in spleen compared with the corresponding cells from the marrow and spleen of Gata1low/0 mice is consistent with the splenic microenvironment of the mutant mice being more supportive of hematopoiesis compared with the marrow microenvironment (Table 1).

To assess the functionality of cells purified from the different experimental groups, colony assays at limiting dilution were performed. In −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 males, the cKitpos cells purified from the marrow had greater colony-forming potential than the corresponding spleen populations (cloning efficiency: 14%-60% vs 0%-0.2%, respectively; Table 1). By contrast, in −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 mice, the cKitpos cells purified from the spleen had greater cloning efficiency than those purified from the marrow (18-72 vs 0.1-23).

These results indicated that the inability of Gata1low stem/progenitor cells to produce hematopoietic colonies is rescued in the spleen by a mechanism that allows the cells to activate the HS2 enhancer.

Gata1low/0 erythroid cells in the spleen expressed high levels of Gata1 and Gata2 and were not maturation impaired

To clarify the mechanism that rescued the erythroid defect induced by the mutation, the levels of GFP, Gata1, and Gata2 expressed by immature and mature erythroid cells prospectively isolated according to the levels of CD71 and Ter119 expression28 from the marrow and spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 and −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 males were determined (Figure 4B and Tables 1–2).

In−2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 mice, the frequency of erythroid cells was higher in the marrow than in the spleen (Table 1) and the levels of GFP expression decreased with erythroid maturation (Figure 4B and Table 1). As expected,31 in the marrow of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 mice, the frequency of mature (CD71med) erythroid cells was significantly lower than normal (1.8% vs 10.2%; Table 1). By contrast, in the spleen of these mutant mice, the frequency of both immature and mature erythroid cells was normal, indicating that immature Gata1low/0 erythroblasts in the spleen undergo apoptosis at rates lower than those occurring in the marrow. These Gata1low/0 precursors in the spleen expressed the reporter gene at levels higher than those expressed by the corresponding cells from the marrow of the same animals or from either the marrow or spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 mice, indicating that these cells used the alternative HS2 enhancer.

As expected,5 both in the marrow and spleen of Gata1+/0 mice, erythroid maturation was associated with increased expression of Gata1 and reduced expression of Gata2. Also in the marrow of Gata1low/0 mice, expression of Gata2 decreased with erythroid maturation but the expression of Gata1 did not increase. By contrast, in the spleen of the mutants, expression of Gata1 increased and that of Gata2 did not decrease with erythroid maturation. These spleen cells expressed all the globin genes at levels higher than those expressed by the corresponding mutant cells from the marrow and of those expressed by normal cells (Table 2).

In conclusion, the erythroid cells in the spleen of Gata1low/0 males expressed high levels of GFP and levels of Gata1 higher than those expressed by erythroid cells from the marrow of Gata1low/0 mice and comparable with those expressed by erythroid cells from the spleen of Gata10/+ mice, consistent with the hypothesis that the spleen is a more permissive microenvironment for Gata1 expression from HS2.

Bipotent Gata1low/0 MKs from the spleen expressed Gata1 driven by the alternative HS2 enhancer

In addition to defects in erythroid cells, MK abnormalities were also rescued in the spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 males. The mechanism that rescued the MK defects induced by the Gata1low mutation was therefore investigated (Figure 4C and Tables 1–2). As expected, the GFP reporter was not expressed by MKs purified from the marrow and barely detectable in those from the spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 mice (Figure 4C). MKs from the marrow of 2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 mice were also GFPneg and expressed levels of Gata1 significantly lower than those expressed by normal MKs. By contrast, the majority (> 95%) of MKs from the spleen of these mutants were GFPpos. The MKs purified from the spleen of the mutant mice expressed levels of Gata1 and of MK-specific proteins similar to, or higher than, those expressed by wild-type MKs (Table 2). However, they also expressed high levels of erythroid-specific genes, approximately 1-log higher than those expressed by the corresponding wild-type cells (either from the marrow or from the spleen). These levels were 4- to 10-fold lower than those expressed by wild-type erythroid cells (compare Figure 4B-C), suggesting that MKs from the spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1+/0 were bipotent for the 2 lineages. The bipotent nature of the Gata1low/0 MKs from the spleen was confirmed by 4-color FACS analyses for coexpression of CD41pos, CD61pos, CD71, and TER119 (data not shown). Bipotent precursors for the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineage (PEMs), that is, cells that express both erythroid and megakaryocyte markers and give rise to mature erythroid cells or MKs, depending whether they are stimulated with EPO or thrombopoietin, in 24 hours were originally described by us in the spleen of phenylhydrazine-treated mice.32 These cells are also present in the spleen of Gata1low mice.31 Because PEMs do not correspond to or derive from MEPs,33 we hypothesized that they may originate from the common myeloid progenitor in the spleen through an alternative maturation pathway.33

In conclusion, MKs from the spleen of −2.7kbGata1GFPGata1low/0 males expressed normal levels of Gata1, probably driven by the HS2 enhancer that preserved their property to develop into erythroid cells.

Gata1low/0 bone marrow cells preferentially engraft the extramedullary sites of the host

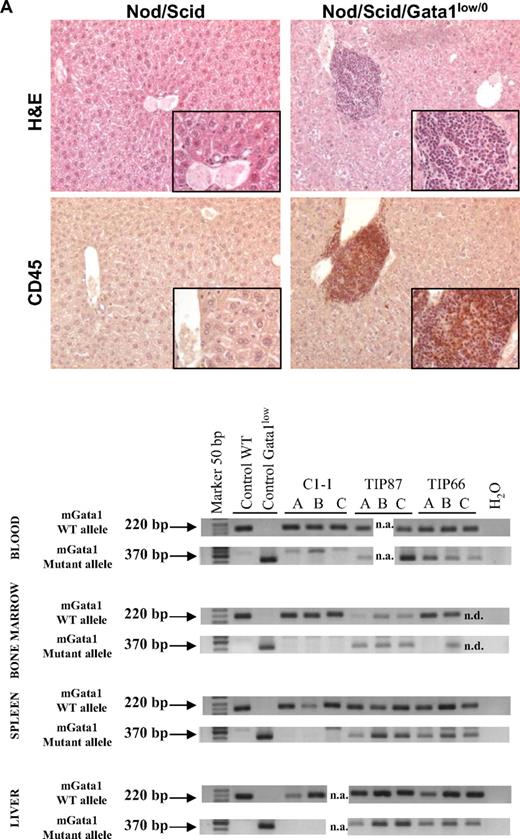

To analyze the engrafting properties of Gata1low/0 stem/progenitor cells, 106 bone marrow cells from 4 mutant males were transplanted into 12 NOD/SCID females (3 recipients per each donor; Figure 5).

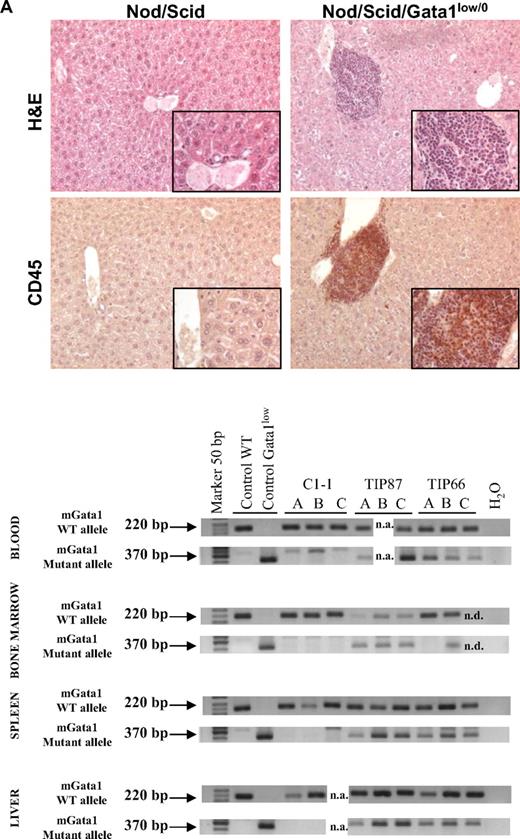

Bone marrow cells from Gata1low mice engraft preferentially the extramedullary sites of the recipients. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin and CD45 immunostaining of liver sections from an untreated NOD/SCID female and from a NOD/SCID female that received a transplant of bone marrow cells from a Gata1low/0 male. The presence of cells with the Gata1+ (220 bp, 2 alleles per cell) and Gata1low (370 bp, one allele per cell) genotype in blood, bone marrow, spleen, and liver of representative NOD/SCID mice that received a transplant from either wild-type (C1-1) or Gata1low (2 mice, TIP87 and TIP 66) mice is presented on the bottom. Results are representative of those obtained in 12 animals that underwent transplantation. Magnification ×20 in the panels and ×40 in the insets. (B) Frequency of cells expressing a lymphocyte (B220pos or CD4pos), granulomonocyte (Mac3pos or Gr1pos), and MK (CD41pos/CD61pos) phenotype in the blood and of those expressing a stem cell (Sca1pos/CD117pos), erythroid (CD71pos/TER119pos), and MK (CD41pos/CD61pos) phenotype in the marrow, spleen, and liver of a representative NOD/SCID mouse that received a transplant 2 months earlier of 106 Gata1low bone marrow cells. Similar results were observed in 6 additional mice that underwent transplantation. The presence of cells with the Gata1+ (220 bp) and Gata1low (370 bp) genotype among the individual populations purified by sorting (> 90% pure by reanalysis) was assessed by PCR and presented on the right. Representative PCR analyses of cells purified from 3 representative recipients (each line is an individual mouse; A, B, or C). Representative isotype controls for the FACS analyses are presented in supplemental Figure 3.

Bone marrow cells from Gata1low mice engraft preferentially the extramedullary sites of the recipients. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin and CD45 immunostaining of liver sections from an untreated NOD/SCID female and from a NOD/SCID female that received a transplant of bone marrow cells from a Gata1low/0 male. The presence of cells with the Gata1+ (220 bp, 2 alleles per cell) and Gata1low (370 bp, one allele per cell) genotype in blood, bone marrow, spleen, and liver of representative NOD/SCID mice that received a transplant from either wild-type (C1-1) or Gata1low (2 mice, TIP87 and TIP 66) mice is presented on the bottom. Results are representative of those obtained in 12 animals that underwent transplantation. Magnification ×20 in the panels and ×40 in the insets. (B) Frequency of cells expressing a lymphocyte (B220pos or CD4pos), granulomonocyte (Mac3pos or Gr1pos), and MK (CD41pos/CD61pos) phenotype in the blood and of those expressing a stem cell (Sca1pos/CD117pos), erythroid (CD71pos/TER119pos), and MK (CD41pos/CD61pos) phenotype in the marrow, spleen, and liver of a representative NOD/SCID mouse that received a transplant 2 months earlier of 106 Gata1low bone marrow cells. Similar results were observed in 6 additional mice that underwent transplantation. The presence of cells with the Gata1+ (220 bp) and Gata1low (370 bp) genotype among the individual populations purified by sorting (> 90% pure by reanalysis) was assessed by PCR and presented on the right. Representative PCR analyses of cells purified from 3 representative recipients (each line is an individual mouse; A, B, or C). Representative isotype controls for the FACS analyses are presented in supplemental Figure 3.

After transplantation, NOD/SCID mice expressed a normal hematocrit but the levels of platelets and of white blood cells in their blood significantly decreased and increased, respectively, up to values characteristic for Gata1low/0 mice (194 ± 110 × 106 and 6.7 ± 0.7 × 106 platelets and white blood cells/L, respectively, supplemental Table 4). Robust levels of multilineage donor-derived cells were present in the blood of the mice that underwent transplantation (Figure 5). By Y chromosome–specific PCR, it was determined that at least 20% of the white blood cells in these mice were donor derived. Surprisingly, numerous donor-derived MKs were detected in the blood of the recipients (Figure 5). By contrast, few (0%-008% by Y chromosome–specific PCR) donor-derived cells were detected in the marrow of the recipients, whereas great numbers of donor-derived cells were detected in the spleen (1%-74%) and the liver (1%-12%). PCR analysis for the presence of the Gata1low mutation of prospectively isolated cell populations indicated that donor-derived cKitpos cells were barely detectable in the marrow but were numerous in the spleen of the recipients (Figure 5). In all mice, the majority of the erythroid cells in the spleen and of the MKs in the liver were donor derived (Figure 5).

These results confirm the preferential engraftment of Gata1low stem/progenitor cells to extramedullary microenvironments such as those in spleen and liver.

Discussion

By investigating the mechanism that rescues the hematopoietic defect induced by the Gata1low mutation, this study has provided evidence for the existence of organ-specific microenvironments. In fact, Gata1+/0 and Gata1low/0 stem/progenitor cells were specifically supported by the microenvironment in the marrow and in the spleen, respectively. In addition, Gata1low/0 stem/progenitor cells in the spleen activated a maturation pathway that involved an alternative chromatin configuration of the Gata1 locus that allowed erythroid cells and MKs to express the gene through an alternative enhancer (HS2).

The role of the spleen during recovery from anemia induced by acute stimuli has been previously recognized in mice34-36 and was thought to provide extra space for cell expansion. This notation is supported by the observation that, under steady-state conditions, the incidence of stem/progenitor cells in this organ is as low as that in the blood. The hypothesis that the spleen may contain hematopoietic niches different from those present in the marrow was first suggested by Curry et al37 and La Pushin and Trentin38 on the basis of the observation that hematopoietic foci that developed in the spleen of mice injected with bone marrow cells were composed primarily of erythroid cells. The erythroid cell permissiveness was retained by stromal cell lines derived from the spleen of newborn mice capable of forming capillary-like structures in collagen matrix,39 suggesting that the “erythroid-specific niche” in the spleen was composed of endothelial cells. A more recent publication has extended this hypothesis, indicating that erythropoiesis in the spleen is supported by the BMP4/hedgehog rather than by the stem cell factor/cKit pathway active in the marrow.40 Our data prove the organ specificity of the microenvironment, adding yet another level of complexity by indicating that maturation in the spleen is the result not only of alternative extrinsic signaling pathway(s) but also of alternative intrinsic properties of the stem cells, such as different chromatin configurations of the Gata1 locus. Of note is our observation that Gata1low stem cells lack the expression of CXCR4 that allows hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells to interact with the vascular niche in the marrow.24

Our data do not clarify, however, whether stem cells with alternative chromatin configuration of the Gata1 locus are “unique” to Gata1low mice, or whether these cells are generated also in normal mice at levels below the detection limit of currently available stem cell assays. The latter hypothesis is supported by the recent observation that inactivation of the retinoblastoma gene, or of the gene encoding the γ subunit of the retinoic acid receptor, induces a myeloproliferative phenotype similar to that induced by the Gata1low mutation.41-43 In accordance, these mice exhibit increased levels of circulating stem/progenitor cells and also have extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen. In contrast with the phenotype induced by the Gata1low mutation, however, the myeloproliferative trait induced by these inactive genes segregates with the genotype of the host microenvironment and not with that of the donor stem cells. This observation suggests that these mutations might activate organ-specific microenvironments that allow proliferation of subsets of distinct “stem cells” ultimately responsible for the myeloproliferative phenotype. Additional indirect support for this hypothesis is provided by our own observation that the myeloproliferative defect induced by the presence of the Gata1low mutation in heterozygous Gata1low/+ females is cured by removal of the splenic microenvironment.

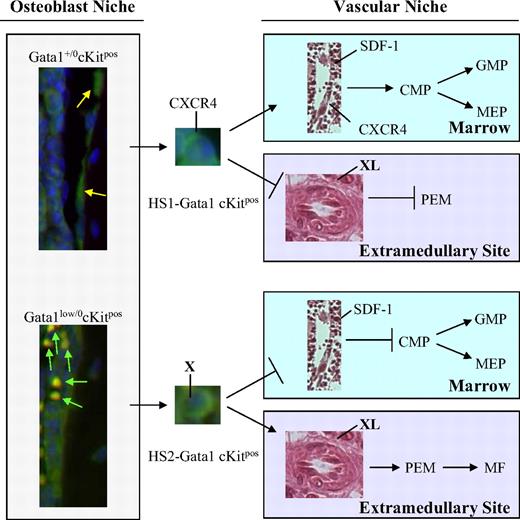

The current model of lineage specification in hematopoiesis is based on the premise that this process is an orderly sequence of restrictive events1 driven by discrete increases in concentration of lineage-restricted transcription factors.44 This hypothesis led to the development of mathematical models to predict lineage commitment based on gradients of transcription factor concentrations.45 Lineage specification, however, can also be modeled according to the existence of crossing points, such as those described between the lymphoid-myeloid and the erythroid-MK lineages, that allow skipping the orderly sequence of restriction events33,46 (and this paper). The data presented in this paper suggest that these crossing points are represented by epigenetic alterations of the chromosomal configuration of transcription factor loci. This premise paves the way to a genome-based model of cell fate in hematopoiesis. This model hypothesizes that the Gata1 enhancer, the efficient HS1 or the inefficient HS2, that is activated when the stem cell exits from quiescence is an integral part of the differentiation program and will determine whether the progeny of this cell will interact with the vascular niche in the marrow, undergoing orderly commitment, or with that in the spleen, skipping lineage restriction (Figure 6). The data presented in this paper provide the first indication of the existence of interplay between organ-specific microenvironments and epigenomically alternative stem cells.

A Gata1 enhancer–based model for the rescue of the hematopoietic defects induced by the Gata1low mutation. Normal quiescent cKitpos hematopoietic stem cells (HSCG0) adhere to the endosteum of the bone2-4 and do not express GFP (Figure 4). Once these cells are induced into cycle, they leave the osteoblast niche to lodge in the vascular niche of the marrow and begin the commitment process leading to the generation of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), granulomonocytic progenitors (GMPs), and megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitors (MEPs).29 Expression of Gata1 in these progenitors is driven by the HS1 enhancer.47 By contrast, in Gata1low mice, a higher proportion of the cKitpos cells adheres to the osteoblast niche. These cells are GFPpos and, therefore, have the potential to activate the HS2 enhancer. Because Gata1lowcKitpos cells do not express CXCR4,24 once induced to cycle, they can no longer lodge in the vascular niche in the marrow. These cells, however, retain the ability to lodge in the spleen microenvironment (Figures 3 and 5), which is capable of sustaining maturation of those Gata1low stem/progenitor cells that express Gata1 through the HS2 enhancer (Figure 4). This spleen-specific maturation route occurs through an alternative pathway that involves the generation of bipotent precursor for the erythroid/megakaryocytic lineage (PEM)31-33 (and this paper). It is possible that the adhesion receptor, expressed by the HS2-Gata1 stem cell (X), and its ligand, expressed by the cells in the spleen microenvironment (XL) that mediate this interaction, are represented by BMP4 and Hedgehog, respectively.40

A Gata1 enhancer–based model for the rescue of the hematopoietic defects induced by the Gata1low mutation. Normal quiescent cKitpos hematopoietic stem cells (HSCG0) adhere to the endosteum of the bone2-4 and do not express GFP (Figure 4). Once these cells are induced into cycle, they leave the osteoblast niche to lodge in the vascular niche of the marrow and begin the commitment process leading to the generation of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), granulomonocytic progenitors (GMPs), and megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitors (MEPs).29 Expression of Gata1 in these progenitors is driven by the HS1 enhancer.47 By contrast, in Gata1low mice, a higher proportion of the cKitpos cells adheres to the osteoblast niche. These cells are GFPpos and, therefore, have the potential to activate the HS2 enhancer. Because Gata1lowcKitpos cells do not express CXCR4,24 once induced to cycle, they can no longer lodge in the vascular niche in the marrow. These cells, however, retain the ability to lodge in the spleen microenvironment (Figures 3 and 5), which is capable of sustaining maturation of those Gata1low stem/progenitor cells that express Gata1 through the HS2 enhancer (Figure 4). This spleen-specific maturation route occurs through an alternative pathway that involves the generation of bipotent precursor for the erythroid/megakaryocytic lineage (PEM)31-33 (and this paper). It is possible that the adhesion receptor, expressed by the HS2-Gata1 stem cell (X), and its ligand, expressed by the cells in the spleen microenvironment (XL) that mediate this interaction, are represented by BMP4 and Hedgehog, respectively.40

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Dr David Scadden is gratefully acknowledged for providing the −2.7kbGata1GFP mice. Maria Elena Fabucci is acknowledged for help with the statistical analyses, and Rosanna Botta for providing NOD/SCID mice.

This study was supported by Ministero per la Ricerca Scientifica and Alleanza sul Cancro and the National Cancer Institute, grant no. P01-CA108671.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.R.M. and W.E.F. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; F.M., M. Verrucci, M.S., M. Valeri, G.M., A.M.V., M.Z., A.D.B., B.G., R.A.R., and Y.v.H. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; and all the authors have read the paper and agree with its content.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anna Rita Migliaccio, Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Pl, Box 1079, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: annarita.migliaccio@mssm.edu.