Abstract

Transforming growth factor-β–induced protein (TGFBIp)/βig-h3 is a 68-kDa extracellular matrix protein that is functionally associated with the adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation of various cells. The presence of TGFBIp in platelets led us to study the role of this protein in the regulation of platelet functions. Upon activation, platelet TGFBIp was released and associated with the platelets. TGFBIp mediates not only the adhesion and spread of platelets but also activates them, resulting in phosphatidylserine exposure, α-granule secretion, and increased integrin affinity. The fasciclin 1 domains of TGFBIp are mainly responsible for the activation of platelets. TGFBIp promotes thrombus formation on type I fibrillar collagen under flow conditions in vitro and induces pulmonary embolism in mice. Moreover, transgenic mice, which have approximately a 1.7-fold greater blood TGFBIp concentration, are significantly more susceptible to collagen- and epinephrine-induced pulmonary embolism than wild-type mice. These results suggest that TGFBIp, a human platelet protein, plays important roles in platelet activation and thrombus formation. Our findings will increase our understanding of the novel mechanism of platelet activation, contributing to a better understanding of thrombotic pathways and the development of new antithrombotic therapies.

Introduction

Platelet adhesion and activation are critical initial events in the process of hemostasis and thrombosis.1 Platelet activation is notified by a few characteristic molecular changes such as an increase in the affinity of the fibrinogen receptor, integrin αIIbβ3, changing to procoagulant surface, and α-granule secretion.2-5 These events initially are triggered by subendothelial collagens exposed at sites of blood vessel injury. However, collagen is not exclusively a thrombogenic factor. Initial platelet-collagen interaction is rapidly reversible and insufficient for stable adhesion. Stable adhesion requires additional interaction with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor (VWF). However, injured vessels of mice lacking both fibrinogen and VWF also are occluded by thrombi.6 Various soluble stimuli released from platelets and also existing in plasma, including fibrinogen and fibronectin, strengthen platelet adhesion and recruit more platelets into the growing thrombus.7,8 Interestingly, in the case of fibronectin, families with a congenital deficiency of fibronectin may show abnormal wound healing but no bleeding.9 In conditional knockout mice with reduced plasma fibronectin levels, normal initial platelet adhesion is observed, but thrombus formation is delayed.10 These results led to the suspicion that another adhesive protein may serve as a substitute.

Transforming growth factor-β–induced protein (TGFBIp) has been identified and cloned as a major TGF-β–responsive gene in the lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549: TGF-β–induced gene human clone 3, abbreviated to βig-h3.11,12 It is secreted from several cell lines, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and monocytes and exists in the ECM. It is a 68-kDa protein that consists of 4 fasciclin 1 domains (FAS1 domain) and a carboxy-terminal arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid (RGD) sequence, both of which potentially bind integrins as a cell attachment site. It plays a crucial role in cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation as a ligand of several integrins, such as α3β1, αvβ5, and αvβ3.11-17 As one of the ECM components, TGFBIp is associated with other ECM molecules, including collagen, fibronectin, laminin, and glycosaminoglycan.12 In addition, it also exists in blood and accumulates at inflammatory sites such as fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, diabetic kidney, diabetic angiopathy, and wound healing.18-21 Considering that the expression of TGFBIp in several cell types has been known to be highly induced by TGF-β and TGF-β that is abundantly present in platelets, TGFBIp could possibly be produced in platelets and play an important role in mediating platelet functions. Until now, however, nothing has been reported on the presence of TGFBIp in platelets and its role in platelet functions.

In this report, we established the existence of TGFBIp in human platelets for the first time and discovered that it is released from activated platelets. It can bind to the surface of platelets and can induce platelet activation, resulting in the promotion of thrombogenesis.

Methods

Mice and reagents

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were used. Alb-TGFBIp mice were generated as described previously.22 These mice were maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions, and the use committee established at Medical College of Kyungpook National University and Kyungpook National University Hospital approved the protocol.

Prostaglandin E1 and fibrinogen were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The following mouse monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Chemicon International Inc: anti-α5β1 (MAB1969, for blocking assay), anti-α5β1 (MAB1999, for FACS), and anti-αIIbβ3 (MAB1207). Anti–P-selectin antibody and annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were obtained from BD Pharmingen. Polyclonal rabbit anti-TGFBIp antibody is obtained and purified as described previously.15,16,23 Fibrinogen-FITC was obtained from Invitrogen. Recombinant TGFBIp proteins and each of the domains (Do1, Do2, Do3, Do4, Do4-RGD, and Do1-4) were induced and purified as described previously.15,16 Triton X-114 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to remove endotoxin from bacterial cell lysate.24 The proteins were kept at −20°C for up to 2 months until use.

Platelet isolation and detection of TGFBIp expression

Approval was obtained from the Kyungpook National University Hospital Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood from healthy nonsmoking and aspirin-free donors was collected into polypropylene syringes containing anticoagulant and was used within 3 hours. The final concentration of anticoagulant was 0.38% (wt/vol) sodium citrate. Prostaglandin E1 was added to a final concentration of 1 μmol/L. Platelet-rich plasma was prepared by centrifuging the blood at room temperature for 13 minutes at 230g. Platelets were then pelleted by centrifuging the platelet-rich-plasma at room temperature for 10 minutes at 1000g. The platelet pellets were then washed twice in resuspension buffer (HEPES-buffered Tyrode solution, pH 6.5; containing 5 mmol/L HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 4 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 2.6 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 5 mmol/L glucose, and 1 μg/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA]) containing 5.0 U/mL apyrase. After centrifugation at room temperature for 10 minutes at 1000g, platelets were resuspended to a final concentration of 109 platelets/mL in platelet buffer (5.0 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.3; containing 140 mmol/L NaCl and 1 mg/mL BSA).3 To identify TGFBIp in platelets, washed platelets were allowed to attach to fibronectin. Adherent platelets were immunostained with anti-CD41 and anti-TGFBIp antibodies. For the immunoblotting assay, platelets were activated with thrombin with or without stirring, and the pellet and supernatant were then collected. After sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, we performed an immunoblotting assay with polyclonal rabbit anti-TGFBIp antibody. Surface binding TGFBIp was measured by flow cytometry with an anti-TGFBIp antibody and FITC-conjugated anti–rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG) antibody. For reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), total RNA was extracted from isolated platelets by the use of a commercial kit (Fast Track 2.0; Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed with primers as follows: primer pair for TGFBIp, upstream primer 5′-AGATCGAGGACACCTTTGAG-3′ and downstream primer 5′-TTGTTCAGCAGGTCTCTCAG-3′ (size of the expected products: 184 bp); primer pair for VWF, upstream primer 5′-TCTGTGGATTCAGTGGATGCA-3′ and downstream primer 5′-CGTAGCGATCTCCAATTCCAA-3′ (size of the expected products: 84 bp); primer pair for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), upstream primer 5′-CGAGAATGGGAAGCTTGTCA-3′ and downstream primer 5′-GGAAGGCCATGCCAGTGA-3′ (size of the expected products: 508 bp). The PCRs were conducted as follows: 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 56°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C for 40 cycles.

Platelet adhesion assay

The number of adherent platelets was essentially determined as previously described.25 In brief, 100 μL of 5 × 108 platelets/mL were added to TGFBIp-coated microtiter plates (for adhesion assay on immobilized TGFBIp) or noncoated microtiter plates (for adhesion assay with soluble TGFBIp) with soluble-phase TGFBIp (1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (5 μg/mL) at 37°C for the indicated time. For immobilization of TGFBIp, flat-bottomed 96-well plates were incubated with the indicated concentration of TGFBIp at 4°C overnight. After platelets were allowed to adhere, nonadherent platelets were removed by aspiration, and wells were washed 3 times with 200 μL of Tyrode buffer. The acid phosphatase assay was used to quantitate the number of adherent platelets. In brief, after the adhesion and washing procedure had been performed as described previously, the substrate solution (0.1 mol/L citrate buffer pH 5.4, containing 5 mmol/L p-nitrophenyl phosphate and 0.1% Triton X-100; 150 μL per well) was added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. After the reaction was stopped, the color was developed by the addition of 100 mL of 2N NaOH, and absorbance was finally measured at 405 nm by the use of a microplate reader (Bio-Rad model 550 microplate reader). For the inhibition assay, washed platelets were incubated with the indicated function-blocking antibodies (1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C and were then allowed to adhere.

Spreading assay

A platelet suspension (100 μL containing 5 × 107 platelets) was added to TGFBIp-coated microtiter (for adhesion assay on immobilized TGFBIp) or noncoated microtiter plates (for adhesion assay with soluble TGFBIp) with soluble-phase TGFBIp (1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (5 μg/mL), platelets were allowed to adhere (1 hour or 15 minutes at 37°C), and wells were washed with Tyrode buffer to remove nonadherent platelets. Adherent platelets were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 140 mmol/L NaCl, 3 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L Na2HPO4, and 2 mmol/L KH2PO4; pH 7.4). After washing twice with PBS, the fixed platelets were stained for F-actin with FITC-conjugated phalloidin for 20 minutes and washed with PBS at least 3 times before analysis. Fluorescence was visualized by the use of a Zeiss Axiovert S100 microscope with a monochromatic light source and a charge-coupled device camera. Metamorph software was used for capturing images and subsequent analysis.

In vitro perfusion experiment

Platelet thrombi are formed by the perfusion of whole human blood over fibrillar type I collagen. Glass coverslips immobilized with thrombogenic substrates (collagen type I) were assembled in a parallel plate rectangular flow chamber. Whole blood with or without TGFBIp (at final concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 μg/mL) was perfused through the chamber by aspiration with a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) at an estimated shear stress of 0.2 dyn/cm2 (flow rate of 0.22 mL/min) for 5 minutes. The perfusion chamber was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope for real-time visualization of platelet interactions with the immobilized substrates and platelet-platelet aggregation formation.26 Videos were recorded by the use of StreamPix digital video recording software (Norpix). The frame capture rate was set to 10 frames per second. The area of thrombi formation was analyzed by the use of Metamorph software. Thrombus sizes were measured for at least 5 different fields per experiment.

Flow cytometric analysis

Isolated washed platelets were stained for flow cytometric analysis by the use of a standard indirect procedure. In brief, platelets were incubated with soluble-phase TGFBIp (1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (5 μg/mL) for 15 minutes at room temperature. The samples were then washed and fixed with 1% formaldehyde. Platelets were incubated with annexin V–FITC, fibrinogen-FITC, anti–P-selectin–FITC antibody, or control isotype-matched mouse IgG-FITC for 30 minutes at room temperature. After incubation, platelets were washed and analyzed in a BD FACSAria system.

Thrombosis assays

Pulmonary thromboembolism experiments were performed as described previously.27 In brief, 8-week-old C57BL/6 male mice under anesthesia were injected with 100 μL of saline containing the indicated concentration of collagen or TGFBIp and 100 μg/kg epinephrine via tail vein injection. After 10 minutes, lungs were removed, fixed overnight with 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and images were captured by the use of a Leica DM LS microscope (4×/0.1) and a Spot color digital camera (National Diagnosis).

Data analysis

Results are expressed as the mean plus or minus SD of at least 3 independent experiments. The statistical significance of differences between test groups was used for statistical comparison (Sigma Stat; SPSS Science). Statistical relevance was determined by the use of analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

TGFBIp is present in platelets, secreted upon activation, and then associated with platelets

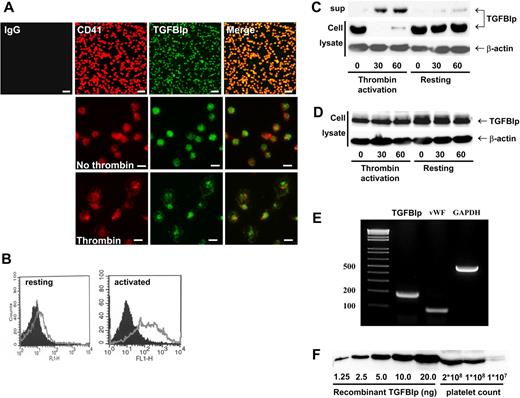

To investigate the expression of TGFBIp in human platelets, isolated platelets from healthy volunteers were allowed to attach to immobilized fibronectin. After washing, adherent platelets were immunostained with anti-CD41 (as a specific platelet marker) and anti-TGFBIp antibodies. As shown in Figure 1A (top), the TGFBIp exists in human platelets. Both TGFBIp and CD41 are located in cytoplasm of platelets in resting condition (Figure 1A middle); however, when they are activated by thrombin, both proteins also are located at the membrane (Figure 1A bottom). The presence of TGFBIp on the surface of activated platelets was further confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) analysis. As shown in Figure 1B, TGFBIp expression was shifted to platelet surface after activation.

Secretion of TGFBIp from activated human platelets and TGFBIp binding on activated platelet surfaces. (A) TGFBIp exists in platelets. Washed platelets were allowed to adhere on fibronectin and were stained with anti-CD41 (red) and anti-TGFBIp (green) antibodies. Attached platelets and TGFBIp expression were observed under a fluorescence microscope. (Top) Low magnification (×400; white bar represents 10 μm). (Middle and bottom) High magnification (×1000; white bar represents 5 μm). (B) TGFBIp on resting (left) and thrombin-activated (right) platelet surfaces was detected by FACS analysis. Black shading denotes immunoglobulin G control, and the gray line denotes TGFBIp. Presence of TGFBIp in resting and activated platelets (thrombin activation) was analyzed by immunoblotting. Washed platelets were incubated with (C) or without stirring (D), during which they were activated by thrombin. Cell (cell lysate) and supernatant (sup) were separated by centrifugation at 18 000g and were immunoblotted by anti-TGFBIp antibody. β-actin was loaded as a control. (E) TGFBIp mRNA exists in platelets. Total RNA was isolated and subject to RT-PCR for the analysis of TGFBIp, VWF, and GAPDH mRNA expression. (F) Measurement of the amount of TGFBIp in platelets. The amount of TGFBIp in platelets was semiquantitatively measured by Western blot analysis.

Secretion of TGFBIp from activated human platelets and TGFBIp binding on activated platelet surfaces. (A) TGFBIp exists in platelets. Washed platelets were allowed to adhere on fibronectin and were stained with anti-CD41 (red) and anti-TGFBIp (green) antibodies. Attached platelets and TGFBIp expression were observed under a fluorescence microscope. (Top) Low magnification (×400; white bar represents 10 μm). (Middle and bottom) High magnification (×1000; white bar represents 5 μm). (B) TGFBIp on resting (left) and thrombin-activated (right) platelet surfaces was detected by FACS analysis. Black shading denotes immunoglobulin G control, and the gray line denotes TGFBIp. Presence of TGFBIp in resting and activated platelets (thrombin activation) was analyzed by immunoblotting. Washed platelets were incubated with (C) or without stirring (D), during which they were activated by thrombin. Cell (cell lysate) and supernatant (sup) were separated by centrifugation at 18 000g and were immunoblotted by anti-TGFBIp antibody. β-actin was loaded as a control. (E) TGFBIp mRNA exists in platelets. Total RNA was isolated and subject to RT-PCR for the analysis of TGFBIp, VWF, and GAPDH mRNA expression. (F) Measurement of the amount of TGFBIp in platelets. The amount of TGFBIp in platelets was semiquantitatively measured by Western blot analysis.

To further study the presence of TGFBIp in resting and activated platelets, we separated platelet-released supernatant and cell lysate by centrifugation. In resting platelets, TGFBIp was found in cell lysate, but after platelets had been activated by thrombin, TGFBIp was located in platelet-released supernatant (Figure 1C). Interestingly, when supernatant was collected without stirring (in this condition, secreted protein from activated platelets can bind to the platelet surface), TGFBIp was found in cell lysate but not in the supernatant (Figure 1D). These results suggest that TGFBIp secreted by activated platelet exists on the platelet surface in association with activated platelet membrane.

To confirm that TGFBIp is produced in platelets, we measured TGFBIp mRNA along with 2 control messages for VWF and GAPDH. As shown in Figure 1E, all 3 mRNAs were detected in platelets, suggesting that TGFBIp is produced in platelets. To quantify the amount of TGFBIp in platelets, we performed a semiquantitative immunoblot assay estimating that 3.4 ng of TGFBIp is present in 108 platelets (Figure 1F).

Immobilized TGFBIp supports adhesion and spread of human platelets

As an ECM protein and a ligand of integrin, TGFBIp mediates the adhesion of various cells. To investigate the role of TGFBIp in platelet adhesion, washed platelets were allowed to attach on immobilized TGFBIp for 1 hour with or without thrombin. Both resting and activated platelet adhesion was found to increase in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A). We confirmed that TGFBIp was properly immobilized in a dose-dependent manner, reaching the plateau at 10 μg/mL (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Next, we tested whether TGFBIp can also mediate the spread of platelets. As shown in Figure 2B-D, TGFBIp efficiently increased platelet spreading. Interestingly, although the adhesion activity of TGFBIp is less than that of fibronectin (Figure 2C), spreading activity was observed in TGFBIp but not in fibronectin (Figure 2D). Platelets adhesion was not induced by boiled TGFBIp (supplemental Figure 2A) and adhesion to TGFBIp was specifically blocked by anti-TGFBIp antibody (supplemental Figure 2B).

Adhesion and spreading of human platelets on immobilized TGFBIp. (A) Washed platelets were allowed to attach to immobilized TGFBIp for 1 hour with or without thrombin. Adhered platelets were detected by the acid phosphatase assay as described in “Platelet adhesion assay.” (B) Washed platelets were attached to BSA, fibronectin (FN), and TGFBIp (each 10 μg/mL) for 1 hour, and attached platelets were stained for anti-CD41 antibody and observed under a fluorescence microscope. The white bar represents 10 μm. The amounts of (C) platelet adhesion and (D) platelet spreading (pixels/cells) in the presence of TGFBIp, BSA, or fibrinogen were determined. Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, and spreading was detected by use of the MetaMorph program. (E) Integrin-dependent platelet adhesion on TGFBIp. After washed platelets were incubated with integrins α5β1 and αIIbβ3, or immunoglobulin G as a control (each 1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes, they were allowed to mix with immobilized TGFBIp (10 μg/mL) or fibronectin (FN; 10 μg/mL) for 1 hour. Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay. (F) Integrin-dependent platelet spreading on TGFBIp. Platelet spreading (pixels/cell) on TGFBIp or fibronection (FN) was detected by use of the MetaMorph program. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA or immunoglobulin G.

Adhesion and spreading of human platelets on immobilized TGFBIp. (A) Washed platelets were allowed to attach to immobilized TGFBIp for 1 hour with or without thrombin. Adhered platelets were detected by the acid phosphatase assay as described in “Platelet adhesion assay.” (B) Washed platelets were attached to BSA, fibronectin (FN), and TGFBIp (each 10 μg/mL) for 1 hour, and attached platelets were stained for anti-CD41 antibody and observed under a fluorescence microscope. The white bar represents 10 μm. The amounts of (C) platelet adhesion and (D) platelet spreading (pixels/cells) in the presence of TGFBIp, BSA, or fibrinogen were determined. Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, and spreading was detected by use of the MetaMorph program. (E) Integrin-dependent platelet adhesion on TGFBIp. After washed platelets were incubated with integrins α5β1 and αIIbβ3, or immunoglobulin G as a control (each 1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes, they were allowed to mix with immobilized TGFBIp (10 μg/mL) or fibronectin (FN; 10 μg/mL) for 1 hour. Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay. (F) Integrin-dependent platelet spreading on TGFBIp. Platelet spreading (pixels/cell) on TGFBIp or fibronection (FN) was detected by use of the MetaMorph program. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA or immunoglobulin G.

To test which integrins are involved in TGFBIp-mediated adhesion, we used monoclonal antibodies that block the function of integrin subunits. The adhesion of platelets to the immobilized TGFBIp was inhibited only by an antibody against integrin α5β1, by 50% (Figure 2E). We also tested other integrin function–blocking antibodies such as αIIbβ3, αVβ3, α2β1, and α6β1, but none of them showed any profound effect on the adhesion of platelets to TGFBIp (data not shown). In contrast, immobilized TGFBIp-induced spreading was inhibited not only by antibodies against integrin α5β1 but also by antibodies against integrin αIIbβ3 (Figure 2F).

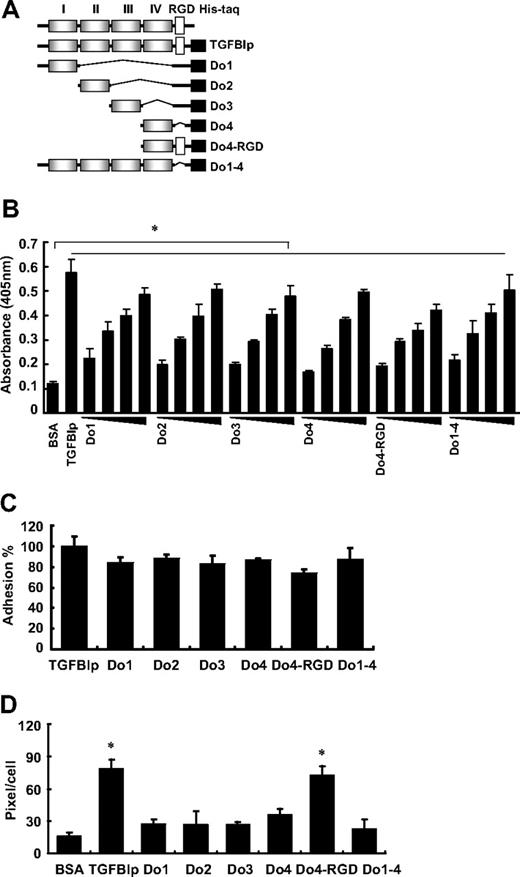

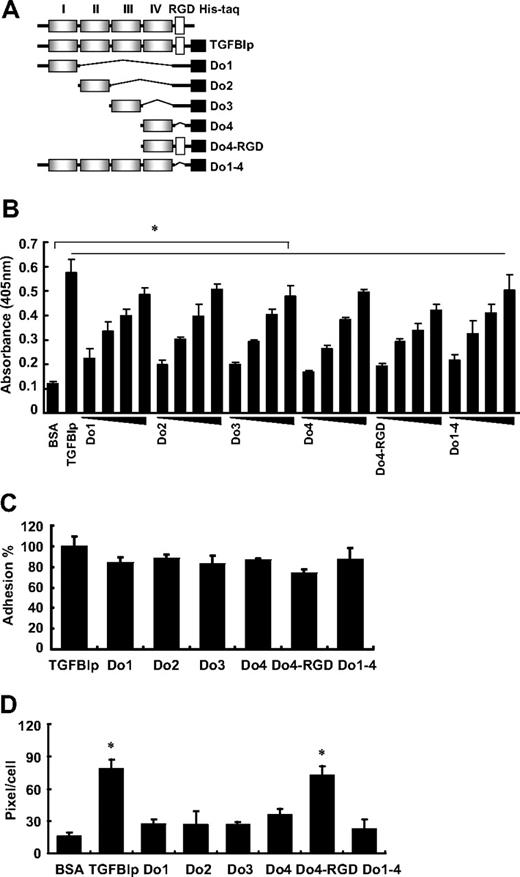

The TGFBIp protein is composed of 4 homologous internal repeat domains, referred to as fasciclin 1 (FAS1), that are known to mediate cell adhesion with the comparable activity to wild-type TGFBIp.16,17,28 To assess whether these FAS1 domains of TGFBIp are involved in platelet adhesion and spreading, washed platelets were incubated with each domain (as shown in Figure 3A) of TGFBIp. The adhesion of platelets to each immobilized FAS1 domain of TGFBIp also was dose dependent (Figure 3B). Each FAS1 domain (Do1, Do2, Do3, and Do4) and Do1-4 is almost equally efficient in mediating platelet adhesion compared with the wild-type TGFBIp (Figure 3C). There was no profound difference between Do4 and Do4-RGD, which suggests that the role of the RGD motif in TGFBIp is dispensable in mediating platelet adhesion. Interestingly, in contrast to adhesion, the spreading of platelets occurred only with wild-type TGFBIp and Do4-RGD (Figure 3D), which suggests the importance of the RGD motif rather than the FAS1 domain of TGFBIp in platelet spreading. Taken together, these results suggest that the FAS1 domain is responsible for the adhesion through integrin α5β1, whereas the RGD motif is responsible for spreading through integrin α5β1 and αIIbβ3.

Adhesion and spreading of human platelets on the FAS1 domain of TGFBIp. (A) Schematic representation of TGFBIp, which consists of 4 homologous internal repeat domains called Fasciclin 1 (FAS1), and various deletion constructs of TGFBIp for each FAS1 and other modifications. (B) Dose-dependent adhesion of the immobilized FAS1 domain of TGFBIp is shown. Washed platelets were allowed to adhere to the indicated FAS1 domain and are presented as platelet adhesion to each immobilized FAS1 domain of TGFBIp (1, 2, 5, and 10 μg/mL). Washed platelet adhesion (C) and spreading (D) on TGFBIp and each of the indicated FAS1 domains were detected. Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, spreading was detected by the use of the MetaMorph program. Results are expressed as a percent of TGFBIp adhesion. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA.

Adhesion and spreading of human platelets on the FAS1 domain of TGFBIp. (A) Schematic representation of TGFBIp, which consists of 4 homologous internal repeat domains called Fasciclin 1 (FAS1), and various deletion constructs of TGFBIp for each FAS1 and other modifications. (B) Dose-dependent adhesion of the immobilized FAS1 domain of TGFBIp is shown. Washed platelets were allowed to adhere to the indicated FAS1 domain and are presented as platelet adhesion to each immobilized FAS1 domain of TGFBIp (1, 2, 5, and 10 μg/mL). Washed platelet adhesion (C) and spreading (D) on TGFBIp and each of the indicated FAS1 domains were detected. Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, spreading was detected by the use of the MetaMorph program. Results are expressed as a percent of TGFBIp adhesion. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA.

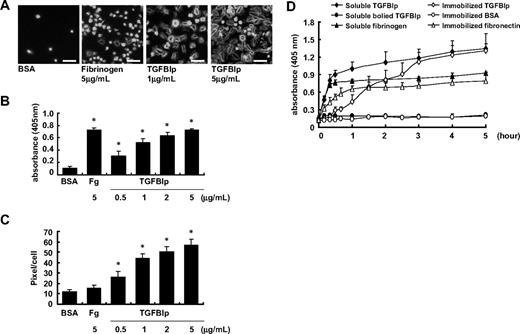

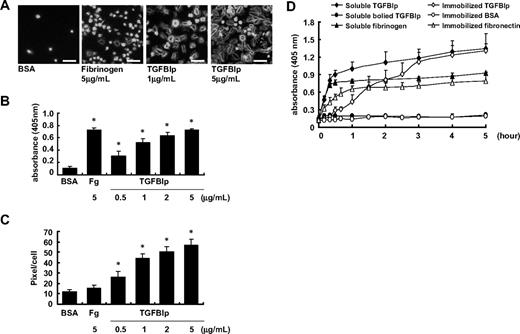

Soluble-phase TGFBIp also induces platelet adhesion and spreading but through different kinetics

We assessed the effect of soluble TGFBIp on platelet adhesion and spreading by transferring the washed platelets to noncoated plates with soluble TGFBIp. Soluble-phase TGFBIp induced adhesion of washed human platelets in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A-B), with adhesion activity comparable with that of soluble fibrinogen. Soluble-phase TGFBIp also induced platelet spreading, whereas fibrinogen did not (Figure 4C).

Effect of soluble TGFBIp on platelet. A platelet suspension (100 μL containing 5 × 107 platelets) was added to a noncoated chamber slide with soluble-phase TGFBIp (1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (5 μg/mL). Platelets were allowed to adhere (15 minutes at 37°C), and wells were washed with Tyrode buffer. (A) Fixed platelets were stained for F-actin with FITC-conjugated phalloidin and were observed under a fluorescence microscope. The white bar represents 10 μm. Representative of platelet adhesion (B) and platelet spreading (pixels/cells) (C) in the presence of soluble-phase TGFBIp (0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (Fg; 5 μg/mL). Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, spreading was detected using the MetaMorph program. (D) Time course adhesion of human washed platelets by soluble and immobilized TGFBIp. Platelet suspensions containing the indicated protein were dispensed in triplicate wells of microplates. After unbounded platelets were removed, adherent platelets were detected by the acid phosphatase assay as described in “Platelet adhesion assay.” All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA.

Effect of soluble TGFBIp on platelet. A platelet suspension (100 μL containing 5 × 107 platelets) was added to a noncoated chamber slide with soluble-phase TGFBIp (1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (5 μg/mL). Platelets were allowed to adhere (15 minutes at 37°C), and wells were washed with Tyrode buffer. (A) Fixed platelets were stained for F-actin with FITC-conjugated phalloidin and were observed under a fluorescence microscope. The white bar represents 10 μm. Representative of platelet adhesion (B) and platelet spreading (pixels/cells) (C) in the presence of soluble-phase TGFBIp (0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (Fg; 5 μg/mL). Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, spreading was detected using the MetaMorph program. (D) Time course adhesion of human washed platelets by soluble and immobilized TGFBIp. Platelet suspensions containing the indicated protein were dispensed in triplicate wells of microplates. After unbounded platelets were removed, adherent platelets were detected by the acid phosphatase assay as described in “Platelet adhesion assay.” All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA.

Next, we incubated washed platelets with soluble-phase TGFBIp or boiled TGFBIp protein on noncoated plates for various indicated time intervals. As shown in Figure 4D, we found that soluble TGFBIp-induced platelet adhesion was initiated from 10 minutes after incubation and nearly reached the peak within 1 hour, followed by a marginal increase, whereas the adhesion of platelets to immobilized TGFBIp was initiated more slowly after incubation. Platelet adhesion was not observed until 30 minutes of incubation and reached the peak at 3 hours of incubation. Therefore, platelet adhesion induced by soluble-phase TGFBIp occurred faster than that induced by immobilized TGFBIp, and soluble TGFBIp is more likely to activate platelets before directly mediating adhesion and spreading by itself.

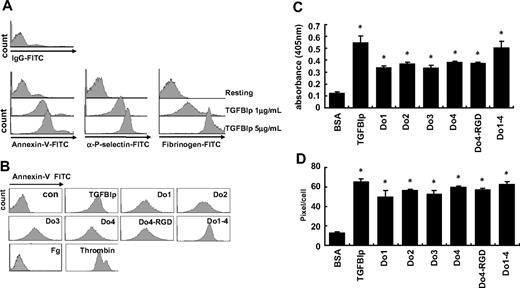

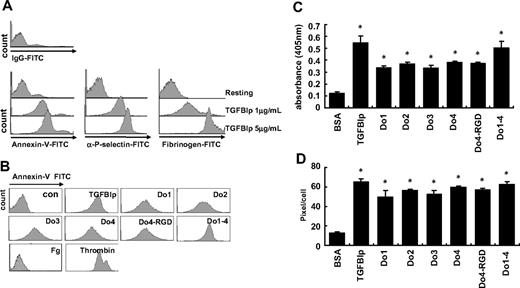

Soluble TGFBIp induces platelet activation

To address the role of TGFBIp in activating platelets, we analyzed phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure, P-selectin exposure, and integrin αIIbβ3 binding affinity after the stimulation of platelets with TGFBIp. After washed platelets were incubated with soluble TGFBIp for 15 minutes, PS and P-selectin exposure were detected by annexin V-FITC and anti–P-selectin–FITC antibody, respectively. Likewise, integrin αIIbβ3 binding affinity was examined by fibrinogen binding activity. As shown in Figure 5A, all 3 platelet activation markers were increased by TGFBIp treatment in a dose-dependent manner, showing the clear role of soluble TGFBIp in platelet activation.

Platelet activation by soluble TGFBIp. (A) Washed platelets were incubated with soluble TGFBIp (1 μg/mL) for 15 minutes. Phosphatidylserine and P-selectin exposure and binding affinity of fibrinogen were detected by annexin V–FITC, anti–P-selectin-FITC antibody, and fibrinogen-FITC, respectively, by the use of FACS analysis. (B) Washed platelets were incubated with the soluble FAS1 domain (Do1, Do2, Do3, Do4, Do4-RGD, and Do1-4; each 1 μg/mL), fibrinogen (Fg; 5 mg/mL, as negative control), and thrombin (1 U/mL, as positive control) for 15 minutes, and PS exposure (annexin V–FITC) was analyzed by FACS. Washed platelets were allowed to adhere on noncoated slides for 15 minutes, and platelet adhesion (C) and platelet spreading (D) were assessed (pixels/cells) in the presence of soluble each indicated protein (1 μg/mL). Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, and spreading was detected by the use of the MetaMorph program. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA.

Platelet activation by soluble TGFBIp. (A) Washed platelets were incubated with soluble TGFBIp (1 μg/mL) for 15 minutes. Phosphatidylserine and P-selectin exposure and binding affinity of fibrinogen were detected by annexin V–FITC, anti–P-selectin-FITC antibody, and fibrinogen-FITC, respectively, by the use of FACS analysis. (B) Washed platelets were incubated with the soluble FAS1 domain (Do1, Do2, Do3, Do4, Do4-RGD, and Do1-4; each 1 μg/mL), fibrinogen (Fg; 5 mg/mL, as negative control), and thrombin (1 U/mL, as positive control) for 15 minutes, and PS exposure (annexin V–FITC) was analyzed by FACS. Washed platelets were allowed to adhere on noncoated slides for 15 minutes, and platelet adhesion (C) and platelet spreading (D) were assessed (pixels/cells) in the presence of soluble each indicated protein (1 μg/mL). Platelet adhesion was detected by the acid phosphatase assay, and spreading was detected by the use of the MetaMorph program. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with BSA.

Further, we attempted to determine whether the FAS1 domains of TGFBIp also can mediate platelet activation by measuring PS exposure upon treatment of each FAS1 domain. Similar to TGFBIp, PS exposure was increased by each FAS1 domain (Do1, Do2, Do3, and Do4), Do4-RGD, and Do1-4 (Figure 5B). We measured another activation marker, phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase, which was found to be markedly increased not only by TGFBIp but also by each FAS1 domain (data not shown). As expected, each FAS1 domain mediated washed platelet adhesion (Figure 5C) and spreading (Figure 5D), but their individual activities were somewhat lower than that of TGFBIp. Interestingly, RGD does not seem to play a role in the activation of platelets by TGFBIp because there was no significant difference between Do4 and Do4-RGD in mediating adhesion and spread. These results indicate that FAS1 domains of TGFBIp are responsible for the activation of platelets.

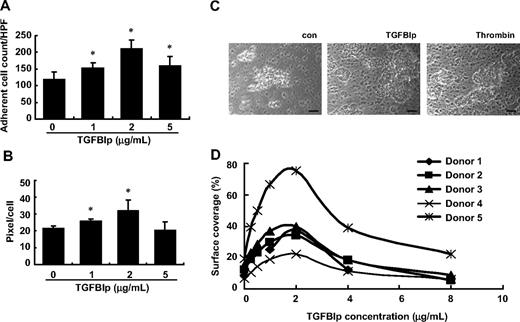

Soluble-phase TGFBIp promotes thrombus formation in vitro

To explore the role of TGFBIp in thrombus formation, we first tested the effect of TGFBIp on platelet deposition to type I collagen under flow conditions. Washed platelet perfusions (5 minutes at shear rate 500−1) over type I collagen were performed in the presence or absence of soluble TGFBIp, and platelet deposition was monitored. In the presence of 2 μg/mL TGFBIp, the deposition and spread of platelets were significantly increased, but interestingly a greater concentration of TGFBIp (5 μg/mL) did not further enhance the rates of platelet adhesion and spread (Figure 6A-B).

Thrombus formation in vitro by soluble-phase TGFBIp. Washed platelet perfusions (5 minutes at shear rate 500−1) over type I collagen were performed in the absence or presence of soluble TGFBIp (1, 2, and 5 μg/mL). Platelet adhesion (A) and platelet spreading (B) under flow conditions were determined. Aspirin-free donors were perfused over type I collagen in the presence or absence of soluble TGFBIp for 5 minutes, and platelet deposition (thrombus formation) was monitored in vitro. (C) Microscopic picture (×200 magnification) showing thrombus formation in the presence or absence of soluble TGFBIp. The scale bar represents 10 μm. (D) Representative histograms showing the size of thrombus formation at different concentrations (2-8 μg/mL) of TGFBIp. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with 0 μg/mL TGFBIp.

Thrombus formation in vitro by soluble-phase TGFBIp. Washed platelet perfusions (5 minutes at shear rate 500−1) over type I collagen were performed in the absence or presence of soluble TGFBIp (1, 2, and 5 μg/mL). Platelet adhesion (A) and platelet spreading (B) under flow conditions were determined. Aspirin-free donors were perfused over type I collagen in the presence or absence of soluble TGFBIp for 5 minutes, and platelet deposition (thrombus formation) was monitored in vitro. (C) Microscopic picture (×200 magnification) showing thrombus formation in the presence or absence of soluble TGFBIp. The scale bar represents 10 μm. (D) Representative histograms showing the size of thrombus formation at different concentrations (2-8 μg/mL) of TGFBIp. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. *P < .05 compared with 0 μg/mL TGFBIp.

To test the effects of TGFBIp on thrombus formation, a thrombus-formation assay was performed in vitro. Whole blood from aspirin-free donors was perfused over type I collagen in the presence or absence of soluble TGFBIp for 5 minutes, and platelet deposition was monitored. As shown in Figure 6C and D, when soluble TGFBIp was added to whole blood, the surface coverage of generated thrombi was greater than that of whole blood without soluble TGFBIp, and thrombus size was dependent on the concentration of soluble TGFBIp. The surface coverage reached a peak at 2 μg/mL TGFBIp and decreased at greater concentrations. Each FAS1 domain also induced thrombus formation on collagen type I (data not shown). These results suggest that soluble TGFBIp induces thrombus formation in vitro, which is dependent on FAS1 domains.

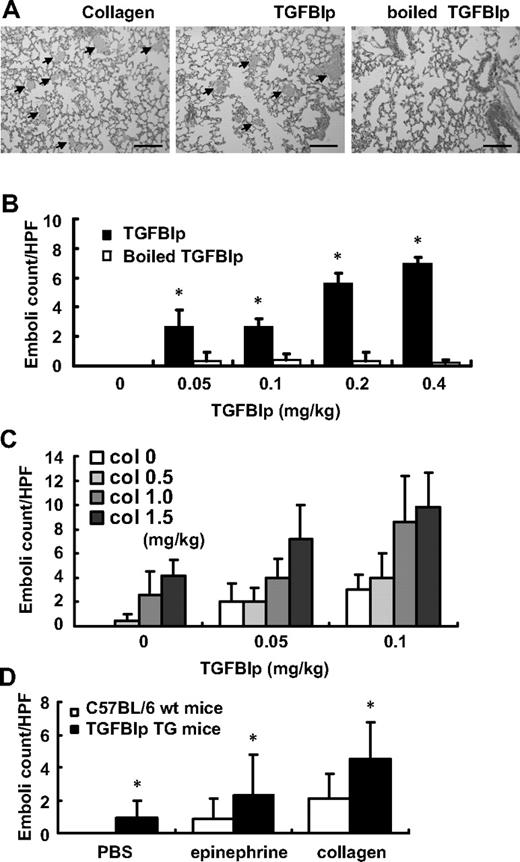

Increased peripheral-blood TGFBIp promotes pulmonary embolism

To determine whether circulating TGFBIp affects thrombus formation in vivo, a collagen/epinephrine mouse model of thrombosis was used.29,30 C57BL/6 mice were given either TGFBIp/epinephrine or boiled TGFBIp/epinephrine via tail vein injection. Microscopic and histologic analysis revealed extensive pulmonary thromboembolism in TGFBIp-injected mice (Figure 7A). As shown in Figure 7B, TGFBIp induced pulmonary embolism in a dose-dependent manner, but boiled protein did not. TGFBIp can induce pulmonary embolism more efficiently than collagen because 0.4 mg/kg TGFBIp induced more than 6-fold greater numbers of thrombi than did 0.5 mg/kg collagen (Figure 7B-C). The thrombogenic activities of TGFBIp seem to act synergistically with collagen because we demonstrated that suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp and collagen-induced dramatic pulmonary embolism, as shown in Figure 7C. This result suggests that TGFBIp can act as a platelet activating factor in vivo, like collagen.

Increased peripheral blood TGFBIp promotes pulmonary embolism. C57BL/6 mice were given with either TGFBIp/epinephrine or a similar volume of boiled protein/epinephrine as a control via tail vein injection. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the lungs of mice (n = 3 per group) given collagen (2 mg/kg), TGFBIp (0.4 mg/kg), and boiled TGFBIp (0.4 mg/kg) is shown. Extensive pulmonary thromboemboli ( ) are shown in collagen- and TGFBIp-injected mice compared with boiled TGFBIp-injected mice. Representative sections (×40 magnification) are shown. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) TGFBIp-induced pulmonary emboli occurred in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Representative of the suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp- and collagen-induced pulmonary embolism. (D) Pulmonary embolism formation in Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice. Mice were intravenously injected with 0.5 mg/kg collagen and 100 μg/kg epinephrine, and the formation of pulmonary emboli was subsequently determined. The pulmonary embolism count was detected in at least 5 different fields. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. * P < .05 compared with 0 mg/kg of the TGFBIp-injected group.

) are shown in collagen- and TGFBIp-injected mice compared with boiled TGFBIp-injected mice. Representative sections (×40 magnification) are shown. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) TGFBIp-induced pulmonary emboli occurred in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Representative of the suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp- and collagen-induced pulmonary embolism. (D) Pulmonary embolism formation in Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice. Mice were intravenously injected with 0.5 mg/kg collagen and 100 μg/kg epinephrine, and the formation of pulmonary emboli was subsequently determined. The pulmonary embolism count was detected in at least 5 different fields. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. * P < .05 compared with 0 mg/kg of the TGFBIp-injected group.

Increased peripheral blood TGFBIp promotes pulmonary embolism. C57BL/6 mice were given with either TGFBIp/epinephrine or a similar volume of boiled protein/epinephrine as a control via tail vein injection. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the lungs of mice (n = 3 per group) given collagen (2 mg/kg), TGFBIp (0.4 mg/kg), and boiled TGFBIp (0.4 mg/kg) is shown. Extensive pulmonary thromboemboli ( ) are shown in collagen- and TGFBIp-injected mice compared with boiled TGFBIp-injected mice. Representative sections (×40 magnification) are shown. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) TGFBIp-induced pulmonary emboli occurred in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Representative of the suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp- and collagen-induced pulmonary embolism. (D) Pulmonary embolism formation in Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice. Mice were intravenously injected with 0.5 mg/kg collagen and 100 μg/kg epinephrine, and the formation of pulmonary emboli was subsequently determined. The pulmonary embolism count was detected in at least 5 different fields. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. * P < .05 compared with 0 mg/kg of the TGFBIp-injected group.

) are shown in collagen- and TGFBIp-injected mice compared with boiled TGFBIp-injected mice. Representative sections (×40 magnification) are shown. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) TGFBIp-induced pulmonary emboli occurred in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Representative of the suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp- and collagen-induced pulmonary embolism. (D) Pulmonary embolism formation in Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice. Mice were intravenously injected with 0.5 mg/kg collagen and 100 μg/kg epinephrine, and the formation of pulmonary emboli was subsequently determined. The pulmonary embolism count was detected in at least 5 different fields. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. * P < .05 compared with 0 mg/kg of the TGFBIp-injected group.

To test whether endogenously produced TGFBIp can induce pulmonary embolism, we used Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice that have approximately 1.7-fold increased serum TGFBIp levels.22 These Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice (TGFBIp TG) exhibited no gross developmental abnormalities, except anterior segment dysgenesis of the eye in some cases,22 and had normal platelet and white blood cell counts (Table 1). Thus, these transgenic mice are suitable for examination of the effect of TGFBIp on platelet function. The transgenic mice did not develop pulmonary emboli, but when they were treated with either epinephrine alone or together with a suboptimal dose of collagen (1 mg/kg), they showed significant development of pulmonary emboli compared with control mice (Figure 7D).

Discussion

Mediators from activated platelets act in an autocrine/paracrine fashion and activate or prime approaching platelets. Here, we show that TGFBIp is secreted from activated platelets and is then associated with the surface of activated platelets in serum factor-free conditions, which suggests that TGFBIp could function as an autocrine and/or paracrine factor. In fact, we showed that exogenously added soluble TGFBIp induced the activation of platelets, resulting in a change in morphology (spreading), PS exposure, α-granule secretion, and increased integrin αIIbβ3 affinity.

TGFBIp mediates the adhesion of several cells through the interaction of the FAS1 domain and integrins.12 Platelets express several integrins, including αIIbβ3, αVβ3, α2β1, α5β1, and α6β1. Among these, integrin αVβ3 is known to interact with TGFBIp in human umbilical vein endothelial cells,11,31 but it does not appear to be responsible for the adhesion of platelets to TGFBIp. Instead, integrin α5β1 is partially responsible for mediating platelet adhesion to TGFBIp because approximately only 50% of platelet adhesion was inhibited by integrin α5β1 function-blocking antibody, which suggests that other integrins or other molecules also are involved in mediating adhesion to TGFBIp. However, it is unlikely that other integrins are involved because we found that several function-blocking antibodies against integrins that have been known to be expressed in platelets did not affect platelet adhesion. TGFBIp is also known to bind proteoglycans such as small leucine-rich biglycan and decorins.12,32 The presence of proteoglycans on human platelets33 suggests that proteoglycans on platelets could be the receptor of TGFBIp.

Integrin αIIbβ3 is the most abundant integrin on platelets and megakaryocytes and is known to play important roles in hemostasis. In resting platelets, αIIbβ3 exists in an inactive conformation. The inactive form of αIIbβ3 does not bind most physiologic ligands, including immobilized fibrinogen and fibronectin. Once integrin αIIbβ3 is activated, it binds several soluble proteins in plasma, including fibrinogen, VWF, and fibronectin. Thus, activation of αIIbβ3 is one of the key processes in thrombogenesis. Collagen, thrombin, and adenosine diphosphate, which are released at sites of vascular injury, have been known to initiate the activation of αIIbβ3. In this report, we show that TGFBIp and its FAS1 domain also trigger αIIbβ3 activation. This finding suggests that TGFBIp plays an important role in thrombogenesis, similar to collagen or thrombin.

The binding of ligands to αIIbβ3 mostly occurs via the RGD sequence, even though its initial adhesion is not mediated by RGD. In the case of fibrinogen, initial cell attachment is mediated by the γ400-411 sequence of fibrinogen, whereas secondary spreading is mediated by the RGD sequence. In addition, other sequences outside of this RGD region are sometimes required for full adhesive activity.34 TGFBIp also contains the RGD motif that could also be involved in platelet spreading. Indeed, TGFBIp mediates the spread of platelets only via its RGD sequence but not via FAS1 domains. Accordingly, the spread of platelets on TGFBIp was inhibited by the αIIbβ3 integrin function-blocking antibody. Our findings suggest that initial adhesion of platelets to immobilized TGFBIp is mediated by FAS1 domains through α5β1, in part, and that their spread is then mediated by the RGD motif via αIIbβ3 integrin.

The adhesion of platelets on immobilized TGFBIp occurred 30 minutes after incubation, whereas soluble-phase TGFBIp initiated adhesion as early as 10 minutes after incubation. Consequently, it seems that soluble TGFBIp activates platelets first and then mediates their adhesion and spread. Upon the binding of ligand, αIIbβ3 elicits a series of outside-in intracellular events that includes activation of kinases and phosphatases, changes in cytoskeletal reorganization, and regulation of protein synthesis. Outside-in signaling through αIIbβ3 amplified events initiated by thrombin and other agonists is necessary for full platelet spreading, platelet aggregation, granule secretion, and the formation of a stable platelet thrombus.35,36 Although it is not clear that soluble TGFBIp binds integrin αIIbβ3, we have shown that soluble TGFBIp and FAS1 domains induce an increase of integrin αIIbβ3 affinity, the phosphorylation of FAK, and a change in cytoskeletal reorganization. Taken together, these findings suggest that soluble TGFBIp is more likely to activate platelets initially, and once it is immobilized in association with other matrix proteins also may mediate the adhesion and spread of platelets.

The first step in the homeostatic cascade is platelet interaction with the exposed ECM at the sites of injury.37 Among the macromolecular constituents of the ECM, collagen is considered to play a major role in this process, because in vitro it not only supports platelet adhesion through direct and indirect pathways, but it also directly activates the cells initiating aggregation and coagulant activity.38 Rapid conversion to stable adhesion requires additional contacts between the platelets and the ECM. TGFBIp is an ECM protein that binds to multiple ligands, including integrins; type I, II, and IV collagen; laminin; fibronectin; and glycosaminoglycan.39,40 At the site of blood vessel injury, TGFBIp may bind to exposed collagen and other matrix molecules. Indeed, we found that when TGFBIp was immobilized with collagen type I or fibrinogen (data not shown), washed human platelet adhesion and spreading was increased. These results indicate that collagen-bound TGFBIp may mediate platelet adhesion and spreading as a cofactor of collagen.

Considering the platelet activation activity of TGFBIp, we addressed the effect of TGFBIp on thrombus formation. We demonstrate that under physiologic flow conditions, TGFBIp promotes thrombus formation on collagen in vitro. The thrombogenic activity of TGFBIp was further confirmed in vivo. Because collagen and epinephrine are initial activating factors of platelets, they can induce pulmonary embolism by intravenous coinjection. Similarly, pulmonary embolism was induced when TGFBIp was administered with epinephrine. Even TGFBIp induced pulmonary emboli at a concentration of 0.05 mg/kg, which is not enough for collagen to induce thrombosis. This finding suggests that TGFBIp is much more potent than type I collagen in inducing thrombus formation. Indeed, 0.4 mg/kg TGFBIp strongly induced pulmonary thrombosis in mice, whereas 0.5 mg/kg collagen barely induced pulmonary thrombosis. Assuming that the average weight of a mouse is 20 g and the average blood volume is 2 mL, the injected TGFBIp concentration, 0.05 mg/kg, is approximately 500 ng/mL in peripheral blood. This concentration is 2.5 times greater than the physiologic concentration of 200 ng/mL. Although Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice have a blood TGFBIp concentration of approximately 340 ng/mL, they are significantly susceptible to the production of pulmonary thrombosis by collagen and epinephrine, which suggests that even a small increase of blood TGFBIp concentration can cause thrombus formation in certain pathologic conditions. Taking all in vitro and in vivo data into consideration, it is strongly suggested that TGFBIp can act as a thrombogenic factor in platelets and blood.

After adhering to vascular lesions, platelets can rapidly recruit additional platelets to the site of injury, which is necessary to achieve hemostasis and can also recruit different types of leukocytes, which set off host defense responses. Activated platelets release inflammatory and mitogenic mediators into the local microenvironment, thereby altering the chemotactic and adhesive properties of monocytes and endothelial cells.41 Activated platelets or platelet microparticles also release chemokines that can trigger the recruitment of monocytes or promote their differentiation into macrophages.42-44 Therefore, TGFBIp, which is capable of activating platelets, is supposed to be actively involved in forming the local microenvironment. In addition, in our previous report, we showed that TGFBIp itself acts as a chemotactic molecule for monocytes and mediates the adhesion of monocytes,17 thus suggesting that a local high concentration of TGFBIp released from or associated with the platelets can also promote monocyte recruitment and mediate heterotypic monocyte-platelet aggregation.

In conclusion, we first demonstrated that TGFBIp is present in the platelets and is released upon activation, and we also present evidence that TGFBIp can activate the platelets, leading to thrombus formation. Our finding will increase understanding of the novel mechanism of platelet activation, contributing to a better understanding of thrombotic pathways, and may subsequently inform the development of new antithrombotic therapies.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (0720550-2); by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST; No. R11-2008-044-03 001-0); by a grant of convergence technology for PET radiopharmaceuticals from the National Research Foundation of Korea; and by the Brain Korea 21 Project in 2009.

Authorship

Contribution: H.-J.K., P.-K.K., and S.M.B. designed and performed experiments; H.-N.S. and J.-E.K. supplied Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice; D.S.T., B.-H.L., and R.-W.P. supervised; I.-S.K. supervised experiments; H.-J.K. and I.-S.K. wrote the manuscript; and D.S.T., B.-H.L., R.-W.P., and I.-S.K. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: In-San Kim, Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Cell and Matrix Research Institute, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, 101 Dongin 2-ga, Jung-gu, Daegu 700-422, Republic of Korea; e-mail: iskim@knu.ac.kr.

) are shown in collagen- and TGFBIp-injected mice compared with boiled TGFBIp-injected mice. Representative sections (×40 magnification) are shown. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) TGFBIp-induced pulmonary emboli occurred in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Representative of the suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp- and collagen-induced pulmonary embolism. (D) Pulmonary embolism formation in Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice. Mice were intravenously injected with 0.5 mg/kg collagen and 100 μg/kg epinephrine, and the formation of pulmonary emboli was subsequently determined. The pulmonary embolism count was detected in at least 5 different fields. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. * P < .05 compared with 0 mg/kg of the TGFBIp-injected group.

) are shown in collagen- and TGFBIp-injected mice compared with boiled TGFBIp-injected mice. Representative sections (×40 magnification) are shown. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) TGFBIp-induced pulmonary emboli occurred in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Representative of the suboptimal doses of both TGFBIp- and collagen-induced pulmonary embolism. (D) Pulmonary embolism formation in Alb-hTGFBIp transgenic mice. Mice were intravenously injected with 0.5 mg/kg collagen and 100 μg/kg epinephrine, and the formation of pulmonary emboli was subsequently determined. The pulmonary embolism count was detected in at least 5 different fields. All results are shown as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments and ANOVA. * P < .05 compared with 0 mg/kg of the TGFBIp-injected group.