The discovery of JAK2V617F as an acquired mutation in the majority of patients with myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs) and the key role of the JAK2-STAT5 signaling cascade in normal hematopoiesis has focused attention on the downstream transcriptional targets of STAT5. Despite evidence of its vital role in normal erythropoiesis and its ability to recapitulate many of the features of myeloid malignancies, including the MPDs, few functionally validated targets of STAT5 have been described. Here we used a combination of comparative genomics and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays to identify ID1 as a novel target of the JAK2-STAT5 signaling axis in erythroid cells. STAT5 binds and transactivates a downstream enhancer of ID1, and ID1 expression levels correlate with the JAK2V617F mutation in both retrovirally transfected fetal liver cells and polycythemia vera patients. Knockdown and overexpression studies in a well-characterized erythroid differentiation assay from primary murine fetal liver cells demonstrated a survival-promoting action of ID1. This hitherto unrecognized function implicates ID1 in the expansion of erythroblasts during terminal differentiation and suggests that ID1 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of polycythemia vera. Furthermore, our findings contribute to an increasing body of evidence implicating ID proteins in a wider range of cellular functions than initially appreciated.

Introduction

Throughout mammalian life there is a continual turnover of the cellular components of the blood, ultimately driven by a small population of hematopoietic stem cells located within the bone marrow.1 Erythropoiesis is first detected within the blood islands of the murine yolk sac at embryonic days 7 to 7.5.2 This first wave of primitive erythropoiesis is transient and erythropoietin independent3 and is replaced by a second wave of definitive erythropoiesis that takes place first within the fetal liver and later in the bone marrow and spleen.1 Unlike primitive erythropoiesis, definitive erythropoiesis is dependent on erythropoietin,4 although terminal differentiation and enucleation of late basophilic erythroblasts is erythropoietin independent.5 Erythropoietin levels regulate red cell production by regulating the rate of apoptosis within developing erythroblasts.6 When circulating erythropoietin levels are low, a high proportion of erythroblasts undergoes apoptosis; increasing levels of erythropoietin rescue an increasing proportion of the total erythroblasts from apoptosis, thereby increasing the rate of production of mature red cells.7

Signaling by the erythropoietin receptor is critically dependent on the cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase JAK28 and leads, among other things, to the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor STAT5.9 JAK2-STAT5 signaling has taken on a new clinical significance since the discovery of an acquired mutation in the JAK2 gene in patients with myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs).10,–12 The JAK2V617F mutation is found in more than 95% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV) and in approximately 50% of those with essential thrombocythemia (ET) and idiopathic myelofibrosis.13,,–16 Several observations suggest that the JAK2V617F mutation produces an increased erythroid drive and that the level of the resulting signaling influences the degree to which erythropoiesis is stimulated. (1) Retroviral and transgenic mouse models demonstrate that mutant JAK2 produces an erythrocytosis in vivo and are consistent with the concept that an increased copy number of mutant JAK2 alleles results in a more erythroid phenotype.17,,,,–22 (2) JAK2V617F-positive patients with ET and idiopathic myelofibrosis have increased blood hemoglobin levels, increased bone marrow erythropoiesis, and/or reduced serum erythropoietin levels compared with those negative for the JAK2V617F mutation.23,24 (3) Subclones homozygous for the V617F mutation are common in patients with overt PV but not in those with JAK2V617F positive ET.25 (4) Patients with no V617F mutation but who have JAK2 exon 12 mutations define a subtype of PV characterized by an isolated and more marked increase in erythropoiesis, which is associated with increased levels of activation of downstream signaling pathways compared with patients with the V617F mutation.26

Both JAK2V617F and constitutively active forms of STAT5 recapitulate many of the features of PV both in vitro14,27,28 and in vivo.17,19,29 Consistent with an important role for STAT5 in erythropoiesis, constitutively active forms of STAT5 can drive terminal erythroid differentiation in the absence of both the erythropoietin receptor and JAK2.30 The originally reported knockout mouse for Stat5a and Stat5b had surprisingly normal adult hematopoiesis,31 but it has recently been appreciated that this knockout mouse, now referred to as Stat5a/bΔN/ΔN, actually produces N-terminally truncated forms of both Stat5a and Stat5b that can activate at least a subset of Stat5 transcriptional targets.32 A more recent, true knockout mouse, Stat5a/b−/− has a much more severe hematopoietic phenotype, with profound anemia resulting in almost complete perinatal lethality,32 emphasizing the importance of Stat5 in normal erythropoiesis. This appears to be due to increased apoptosis and the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL has been demonstrated to be a direct transcriptional target of Stat5.32

Here we report that Id1, a gene implicated in the regulation of several cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, cellular immortalization, hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal,33,–35 and tumorigenesis,36 is directly regulated by Jak2-Stat5 signaling during normal erythropoiesis. Studies of murine fetal liver erythropoiesis demonstrate that Id1 promotes cell survival during terminal differentiation. Moreover, analysis of individual colonies grown from the erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-Es) from PV patients shows that JAK2V617F is associated with increased expression of ID1. Taken together, these data implicate ID1 in the regulation of normal erythropoiesis and in the pathogenesis of PV.

Methods

Cell culture

The HEL cell line (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures) was grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with fetal calf serum (10% by volume), penicillin (100 mg/mL), and streptomycin (100 U/mL; all from Sigma-Aldrich). The 293T cell line was grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal calf serum (10% by volume), penicillin (100 mg/mL), and streptomycin (100 U/mL).

JAK2 inhibition assays

JAK2 inhibition assays were performed using JAK Inhibitor I (Calbiochem, Merck Chemicals Ltd) and AT9383 (Astex Therapeutics). HEL cells (107) were treated with JAK inhibitor (JAK inhibitor I or AT9383, both at a final concentration of 1 μM) or vehicle (DMSO) and RNA extracted from the cells 4, 8, or 24 hours after application of inhibitor, using Tri-Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Gene expression was determined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a MX3000P real-time PCR machine (Stratagene) and normalized against that of β2-microglobulin. Expression in JAK inhibitor–treated samples was normalized relative to that in the vehicle-treated control.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was carried out as previously described.37 Briefly, proteins were cross-linked to DNA using formaldehyde (0.4%) and the cells lysed. The chromatin was fragmented using a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode SA) and separate immunoprecipitates were produced using immunoglobulin raised against acetyl-Histone H3 (lys9/14) no. 06-599 (Upstate Millipore) and STAT5 (C17) sc-835 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). To investigate the effect of JAK2 on STAT5 binding, some ChIP assays were carried out after 4 hours of treatment with the JAK2 kinase inhibitor TG101209 (TargeGen). TG101209 was used at a final concentration of 0.5 μM.

Transient transfection assays

Cells (107 per transfection) were electroporated with 5 μg luciferase reporter construct and 5 μg pEFBOS-Lac Z β-galactosidase expression vector (the latter as a control for transfection efficiency) using the Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). After electroporation, cells were cultured overnight, and the luciferase and β-galactosidase activity in the lysates from each transfection were measured 24 hours later using a Mediators PhL Luminometer (Aureon Biosystems GmbH).

Stable transfection assays

Stable transfection of the HEL cell line was performed using the Nucleofector II electroporator, solution R, program T-027 (Amaxa Inc) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Linearized reporter construct (5 μg) and linearized neomycin resistance plasmid (0.5 μg) were electroporated into 5 × 106 cells. Immediately after transfection each sample was split into 4 equal parts. Twenty-four hours after transfection Geneticin G418 (final concentration, 0.6 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to the culture to select for transfected cells. The activity of the luciferase reporter constructs was measured 10 to 14 days after transfection. Per replicate, 106 cells were assayed.

In vitro erythroid differentiation assays

In vitro erythroid differentiation assays were performed as previously described38 except as follows. Briefly, livers from E14.5 (C57Bl/6 × CBA) F1 murine embryos were extracted by blunt dissection and homogenized. Lineage-negative hematopoietic progenitor cells were isolated using the MACS Murine Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Lineage-negative cells (2 × 105) were plated onto fibronectin-coated 12-well plates (BD Discovery Labware) and grown in erythroid differentiation medium (IMDM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1% detoxified bovine serum albumin [both from StemCell Technologies], 600 μg/mL holo-transferrin [Sigma-Aldrich], 10 μg/mL recombinant human insulin [Sigma-Aldrich], 2 mM l-glutamine, 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 2 U/mL human recombinant erythropoietin).

Retroviral transfection

Retroviral production was carried out using the pCL-Eco Retrovirus Packaging Vector (Imgenex) and the 293T cell line. shRNA hairpins were designed using the Dharmacon siDESIGN program (available online at http://www.dharmacon.com) and synthesized by Invitrogen. The murine whole-length Id1 cDNA was a generous gift from Professor Barbara Christy (University of Texas at San Antonio). Murine fetal liver cells were infected with retrovirus by centrifugation at 800 g at 30°C for 1.5 hours with 4 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich).

FACS analysis

Samples for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis were stained using antibodies against the surface markers ter119 (APC-conjugated, 1 in 100 dilution; BD) and CD71 (PE-conjugated, 1 in100 dilution; BD). Dead cells were excluded using the 7-aminoactinomycin (7AAD) stain. Annexin V staining was performed using the annexin V Detection Kit I (BD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All analysis was performed using a CyAn ADP analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc). Cell-cycle analysis was performed by fixation in 1% paraformaldehyde, cytoplasmic membrane permeabilization using 70% ethanol/30% PBS, RNase A treatment, and DNA staining using propidium iodide.

BFU-E assays from peripheral blood

All samples were obtained after informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and with approval from the institutional ethics committee of the University of Cambridge. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using Lymphoprep (Axis Shield PLC) according to the manufacturer's protocol and transferred to Methocult (H4531; StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 0.01 U/mL erythropoietin at a density of 105 cells/mL. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 14 days.

Results

The ID1 locus contains a conserved STAT5 consensus sequence that is bound by STAT5 in the human cell line HEL

To identify new STAT5 target genes in the context of the MPDs, we performed in silico genome-wide searches for evolutionarily conserved STAT5 binding sites and identified a STAT5 consensus binding sequence 5.5 kb downstream of the human ID1 promoter within a peak of sequence homology between the human, mouse, and dog genomes (Figure 1A-B). To confirm binding of STAT5 to this region, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed in the human erythroleukemia cell line HEL,39 a cell line derived from a patient with an acute erythroleukemia and that contains the JAK2V617F mutation. Relative to a mock immunoprecipitate (IP), the putative STAT5 binding element was highly enriched in the STAT5 IP (Figure 1C). The same region was also enriched in an IP produced using an antibody for acetylation of lysine 9 in Histone H3 (α-H3AcK9) and in a STAT5 IP produced from peripheral blood CD34+ cells taken from a healthy human donor (data not shown).

The ID1 gene expression is regulated by the JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway. (A) Schematic representation of the human ID1 gene locus with a sequence conservation plot for alignments of the human, mouse, and dog genomes. Peaks of sequence conservation in coding regions of the genome are shown in purple, those in transcribed but not translated regions (3′UTR and 5′UTR) are shown in pale blue, and those in nontranscribed regions are shown in pink. The location of a STAT5 consensus binding sequence 5.5 kb downstream of the ID1 promoter is indicated by an arrowhead. (B) Local alignment of the human, mouse, and dog genomes at the +5.5 element. Nucleotides conserved between all 3 species are highlighted in black; those conserved between 2 of the 3 species are highlighted in gray. A conserved STAT5 consensus binding sequence is highlighted in yellow. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays performed at the ID1 +5.5 element in HEL cells using antibodies against STAT5A/B (α-STAT5) and acetylated histone H3 lysine 9 (α-H3AcK9). A typical result from 2 biologic replicates is shown. (D) Effect of the JAK kinase inhibitor JAK inhibitor I on ID1 transcript levels in HEL cells. (E) A similar experiment to that performed in panel D but using AT9383. (F) Transient and stable transfection of HEL cells with ID1 +5.5 luciferase reporter constructs. A 300-bp length of DNA corresponding to the ID1 +5.5 element was inserted downstream of a luciferase reporter gene under the transcriptional control of the human ID1 promoter and the effect of +5.5 element on the transcriptional activity of the ID1 promoter examined. A similar construct containing a scrambled version of the STAT5 binding site within the +5.5 element (+5.5ΔSTAT5) was tested in a similar way. Shown are the mean and standard error of the mean for 2 independent transfections (each performed in triplicate). (G) Relative ID1 transcript levels in JAK2 wild-type and JAK2V617F heterozygous colonies in 10 individual PV patients. (H) Relative ID1 transcript levels in JAK2 wild-type and JAK2V617F homozygous colonies in 4 PV patients. (I) Summary of the relative expression of ID1 in JAK2V617F-negative, heterozygous, and homozygous BFU-E colonies grown from a total of 13 PV patients. Relative expression in JAK2V617F heterozygous and JAK2V617F homozygous colonies for each individual patient was normalized against that in JAK2V617F-negative colonies from the same patient. Each bar represents the mean and SD of the fold increase in ID1 transcript levels in heterozygous and homozygous colonies relative to that in wild-type colonies for each patient (**P < .01; see “Results” for details).

The ID1 gene expression is regulated by the JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway. (A) Schematic representation of the human ID1 gene locus with a sequence conservation plot for alignments of the human, mouse, and dog genomes. Peaks of sequence conservation in coding regions of the genome are shown in purple, those in transcribed but not translated regions (3′UTR and 5′UTR) are shown in pale blue, and those in nontranscribed regions are shown in pink. The location of a STAT5 consensus binding sequence 5.5 kb downstream of the ID1 promoter is indicated by an arrowhead. (B) Local alignment of the human, mouse, and dog genomes at the +5.5 element. Nucleotides conserved between all 3 species are highlighted in black; those conserved between 2 of the 3 species are highlighted in gray. A conserved STAT5 consensus binding sequence is highlighted in yellow. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays performed at the ID1 +5.5 element in HEL cells using antibodies against STAT5A/B (α-STAT5) and acetylated histone H3 lysine 9 (α-H3AcK9). A typical result from 2 biologic replicates is shown. (D) Effect of the JAK kinase inhibitor JAK inhibitor I on ID1 transcript levels in HEL cells. (E) A similar experiment to that performed in panel D but using AT9383. (F) Transient and stable transfection of HEL cells with ID1 +5.5 luciferase reporter constructs. A 300-bp length of DNA corresponding to the ID1 +5.5 element was inserted downstream of a luciferase reporter gene under the transcriptional control of the human ID1 promoter and the effect of +5.5 element on the transcriptional activity of the ID1 promoter examined. A similar construct containing a scrambled version of the STAT5 binding site within the +5.5 element (+5.5ΔSTAT5) was tested in a similar way. Shown are the mean and standard error of the mean for 2 independent transfections (each performed in triplicate). (G) Relative ID1 transcript levels in JAK2 wild-type and JAK2V617F heterozygous colonies in 10 individual PV patients. (H) Relative ID1 transcript levels in JAK2 wild-type and JAK2V617F homozygous colonies in 4 PV patients. (I) Summary of the relative expression of ID1 in JAK2V617F-negative, heterozygous, and homozygous BFU-E colonies grown from a total of 13 PV patients. Relative expression in JAK2V617F heterozygous and JAK2V617F homozygous colonies for each individual patient was normalized against that in JAK2V617F-negative colonies from the same patient. Each bar represents the mean and SD of the fold increase in ID1 transcript levels in heterozygous and homozygous colonies relative to that in wild-type colonies for each patient (**P < .01; see “Results” for details).

To confirm that STAT5 binding is JAK2 kinase dependent, ChIP experiments were performed on HEL cells with and without 4 hours of treatment with the specific JAK2 kinase inhibitor TG101209. These demonstrated a specific reduction of STAT5 binding over the STAT5 consensus sequence in the presence of the JAK2 inhibitor (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Taken together, these results demonstrate the presence of a regulatory element 5.5 kb downstream of the ID1 promoter, which is bound by STAT5 and may function as a transcriptional enhancer, and that will hereafter be referred to as the ID1 +5.5 element.

ID1 is a downstream target of JAK2 signaling in HEL cells

JAK kinase inhibitors were used to investigate regulation of ID1 expression by JAK-STAT signaling in HEL cells. To confirm inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway, expression of BCL-xL and PIM1, 2 known transcriptional targets of STAT5 in myeloid cells, were also examined. Treatment with JAK inhibitor I (a pan JAK kinase inhibitor) led to a 50% reduction in BCL-XL and PIM1 transcripts and a 65% reduction in ID1 transcript levels after 4 hours of exposure to the inhibitor (Figure 1D). By comparison, there was little effect on either GATA1 or STAT5A expression, 2 genes known to be important in erythroid differentiation, making a nonspecific effect of the JAK inhibitor on gene expression unlikely. A more marked reduction in the level of ID1, BCL-XL, and PIM1 transcripts was obtained using the specific JAK2 kinase inhibitor AT9383 (Figure 1E).

To investigate the function of the ID1 +5.5 element, we generated reporter constructs that contained a luciferase gene under the transcriptional control of the endogenous ID1 promoter, with or without a 300-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the +5.5 element. The presence of the +5.5 element led to a 3-fold increase in ID1 promoter activity in transient transfection assays in HEL cells, whereas scrambling the STAT5 consensus site within the sequence of the +5.5 element largely abolished enhancer activity (Figure 1F). Similar results were obtained with stable transfection of HEL cells (Figure 1F). Taken together, our data indicate that ID1 transcription in HEL cells is positively regulated by the JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway via an enhancer element 5.5 kb downstream of the ID1 promoter.

ID1 expression positively correlates with JAK2V617F mutation status in BFU-E colonies grown from patients with PV

We next proceeded to investigate whether ID1 expression is altered in adult erythroid cells from patients with PV. Colonies grown from erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-Es) taken from the peripheral blood of 13 patients with PV were grown in low (0.01 U/mL) erythropoietin conditions. Individual colonies were harvested and their JAK2 mutation status was determined using allele-specific PCR. Colonies of a given genotype were then pooled for RNA extraction and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR was used to assess ID1 transcript levels. In 9 of the 10 patients in whom JAK2V617F heterozygous colonies were obtained, JAK2V617F heterozygous BFU-Es expressed increased levels of ID1 transcript compared with JAK2V617F-negative BFU-Es taken from the same patient (Figure 1G). Similarly, in 4 of the 5 patients in whom JAK2V617F homozygous colonies were obtained, JAK2V617F homozygous colonies expressed increased levels of ID1 transcript compared with JAK2V617F-negative colonies (Figure 1H). Overall, there was a statistically significant 60% increase in ID1 transcript levels in heterozygous colonies and an 80% increase in homozygous colonies compared with JAK2V617F-negative colonies (Figure 1I; Kruskal-Wallis test, P < .001; Dunn post hoc analysis: wild-type versus heterozygous, P < .01; wild-type vs homozygous, P < .01; heterozygous vs homozygous, P > .05). Thus, ID1 expression is higher in JAK2V617F-positive adult erythroid colonies grown from the blood of PV patients, compared with JAK2V617F-negative colonies grown from the same patient.

Id1 is a target of Jak2V617F in murine erythroid progenitor cells

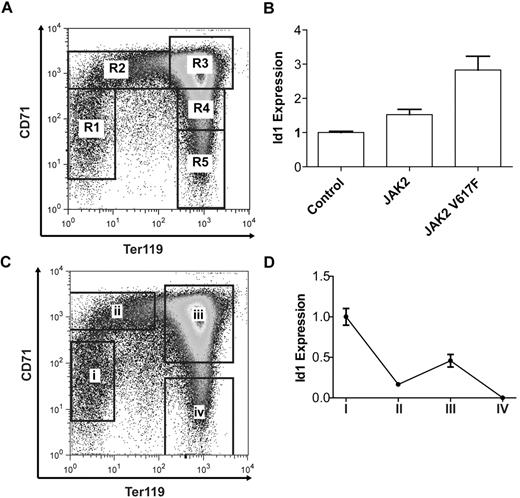

To study the functional significance of Id1 as a transcriptional target of Jak2-Stat5 signaling in erythroid cells, murine fetal liver erythropoiesis was used as a tractable model of terminal definitive erythroid differentiation. In the murine fetal liver, 5 sequential stages of erythroid differentiation (R1-R5) can be identified by FACS analysis, based on the expression of ter119 and CD71 markers38 (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the in vivo differentiation of ter119-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells into mature, enucleated reticulocytes can be recapitulated during in vitro culture over a 2- to 3-day period.38

Id1 expression is dynamically regulated during terminal erythroid differentiation. (A) Ter119 and CD71 expression in E14.5 murine fetal liver cells as determined by FACS and showing 5 sequential stages of erythroid differentiation R1-R5. (B) Id1 transcript levels after 24 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells overexpressing Jak2 or Jak2V617F. (C) Four populations of murine E14.5 fetal liver cells: (i) Ter119−CD71−, (ii) Ter119−CD71+, (iii) Ter119+CD71+, and (iv) Ter119+CD71−, isolated by flow cytometry and representing sequential stages of erythroid differentiation. (D) Id1 transcript levels in the 4 sorted erythroid populations as determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Id1 transcript levels are bimodal with peaks of expression in ter119−CD71− and Ter119+CD71+ cell populations.

Id1 expression is dynamically regulated during terminal erythroid differentiation. (A) Ter119 and CD71 expression in E14.5 murine fetal liver cells as determined by FACS and showing 5 sequential stages of erythroid differentiation R1-R5. (B) Id1 transcript levels after 24 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells overexpressing Jak2 or Jak2V617F. (C) Four populations of murine E14.5 fetal liver cells: (i) Ter119−CD71−, (ii) Ter119−CD71+, (iii) Ter119+CD71+, and (iv) Ter119+CD71−, isolated by flow cytometry and representing sequential stages of erythroid differentiation. (D) Id1 transcript levels in the 4 sorted erythroid populations as determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Id1 transcript levels are bimodal with peaks of expression in ter119−CD71− and Ter119+CD71+ cell populations.

To confirm that Id1 is a transcriptional target of Jak2-Stat5 signaling in this system, murine Jak2 or Jak2V617F was overexpressed in E14.5 lineage-negative fetal liver cells and Id1 transcript levels were determined after 24 hours. Overexpression of Jak2V617F resulted in a 2.9-fold increase in Id1 transcript levels compared with control, whereas overexpression of wild-type Jak2 was associated with a smaller 1.5-fold increase (Figure 2B). To exclude the possibility that Jak2V617F alters Id1 expression secondary to a change in the rate and/or extent of erythroid differentiation, we checked ter119 and CD71 expression by FACS 24 hours after transduction. Overexpression of Jak2 or Jak2V617F had little effect on the rate or extent of erythroid differentiation after 24 hours of culture (supplemental Figure 2). Thus, Id1 expression is positively regulated by Jak2V617F in primary murine fetal liver erythroid progenitors.

To investigate endogenous Id1 expression during murine fetal liver erythropoiesis, E14.5 fetal liver cells were flow sorted into 4 populations representing sequential phases of erythroid differentiation (Figure 2C) and the levels of Id1 transcript in each population determined (Figure 2D). Id1 transcript levels demonstrate a bimodal expression pattern, with higher expression in the first (ter119−CD71−) and third (ter119+CD71+) stages of erythroid differentiation and lower expression in the second (ter119−CD71+) and fourth (ter119+CD71−) stages. Taken together these results demonstrate that Id1 transcript levels are dynamically regulated during fetal liver erythropoiesis and can be modulated by Jak2 signaling.

Id1 promotes erythroblast expansion

To investigate the function of Id1 during fetal liver erythropoiesis, retroviral shRNA was used to knock down Id1 in murine fetal liver erythroid progenitors cultured in vitro. Two shRNA constructs were generated and shown to reproducibly reduce Id1 transcripts by 90% and 95% in murine lineage-negative fetal liver cells (Figure 3A). Due to the limiting amounts of biologic material available from transduced primary fetal liver cells, efficiency of ID1 protein knockdown was assessed in NIH-3T3 cells, which can be easily grown and transduced in large numbers and that are known to express Id1. As expected, knockdown of Id1 mRNA was accompanied by a significant drop in Id1 protein levels (supplemental Figure 3).

shRNA knockdown of Id1 during in vitro erythroid differentiation. (A) Id1 transcript levels after 24 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with shRNA constructs targeting the murine Id1 gene or firefly luciferase (to control for nonspecific cellular effects associated with the processing of an shRNA hairpin). (B) Expansion of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells during in vitro erythroid differentiation. Data (mean and standard deviation) for 1 of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate and showing a similar result, are shown. (C) Relative increase in the number of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or firefly luciferase during 48 hours of in vitro culture. The fold increase in the number of cells transfected with Id1 knockdown constructs after 48 hours of in vitro culture was normalized against that for cells transfected with the construct targeting firefly luciferase. Id1 knockdown is associated with a highly statistically significant 40% to 50% decrease in cell expansion during 48 hours of in vitro culture. Shown is the mean and SEM for 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (**P < .01; ***P < .001; see “Results” for details). (D) Representative FACS plots for ter119 and CD71 expression after 24 and 48 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase. The lefthand panels (0-hours time point) illustrate an identical pool of purified lineage-negative fetal liver cells before retroviral transduction with luciferase or Id1 knockdown constructs and are replicated to facilitate comparison with the panels to their right. Bar charts indicating the proportion of cells at each of the 5 stages of erythroid differentiation (R1-R5) after 24 (E) and 48 (F) hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase. Data (mean and SD) for 1 of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate and showing a similar result, are shown.

shRNA knockdown of Id1 during in vitro erythroid differentiation. (A) Id1 transcript levels after 24 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with shRNA constructs targeting the murine Id1 gene or firefly luciferase (to control for nonspecific cellular effects associated with the processing of an shRNA hairpin). (B) Expansion of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells during in vitro erythroid differentiation. Data (mean and standard deviation) for 1 of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate and showing a similar result, are shown. (C) Relative increase in the number of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or firefly luciferase during 48 hours of in vitro culture. The fold increase in the number of cells transfected with Id1 knockdown constructs after 48 hours of in vitro culture was normalized against that for cells transfected with the construct targeting firefly luciferase. Id1 knockdown is associated with a highly statistically significant 40% to 50% decrease in cell expansion during 48 hours of in vitro culture. Shown is the mean and SEM for 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (**P < .01; ***P < .001; see “Results” for details). (D) Representative FACS plots for ter119 and CD71 expression after 24 and 48 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase. The lefthand panels (0-hours time point) illustrate an identical pool of purified lineage-negative fetal liver cells before retroviral transduction with luciferase or Id1 knockdown constructs and are replicated to facilitate comparison with the panels to their right. Bar charts indicating the proportion of cells at each of the 5 stages of erythroid differentiation (R1-R5) after 24 (E) and 48 (F) hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase. Data (mean and SD) for 1 of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate and showing a similar result, are shown.

Knockdown of Id1 in lineage-negative fetal liver progenitor cells markedly inhibited their expansion during in vitro differentiation (Figure 3B). The results of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, are summarized in Figure 3C and show a significant inhibition of cell expansion by both siRNA constructs (repeated measures one-way analysis of variance, P < .01; Tukey posthoc analysis: control [construct targeting firefly luciferase] vs siRNA 1, P < .01; control vs siRNA 2, P < .001). FACS analysis for ter119 and CD71 expression demonstrated little effect of Id1 knockdown on terminal erythroid differentiation after 24 hours of culture (Figure 3D-E), though a modest but reproducible reduction in the proportion of Id1 knockdown cells in the later stages (especially R4) of erythroid differentiation and a similarly modest increase in the proportion of cells in the earlier stages (most notably R3) after 48 hours of culture were noted (Figure 3D,F).

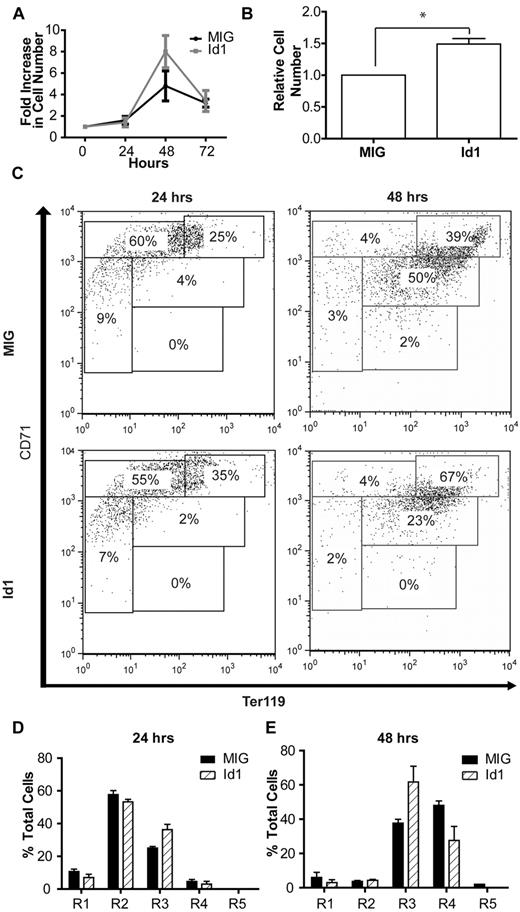

Consistent with the results of the knockdown experiments, overexpression of Id1 produced a modest but reproducible increase in cell expansion (data not shown). This increase became much more apparent when the cells were grown in low erythropoietin concentrations (0.01 U/mL rather than 2 U/mL) thereby minimizing endogenous Id1 transcription, driven by the erythropoietin-Jak2-Stat5 signaling pathway (Figure 4A). The results of 3 such independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, demonstrate a statistically significant 50% increase in the number of Id1-overexpressing cells after 48 hours of culture compared with control (Figure 4B; paired t test, n = 3, P < .05). This was coupled with evidence of impaired terminal differentiation, as indicated by a decrease in the percentage of Id1-overexpressing cells in the R4 stage of differentiation and an increase in the proportion of cells in the R3 stage after 48 hours of culture (Figure 4C,E). Taken together, these data suggest that Id1 plays a significant role in the expansion of erythroblasts during terminal erythroid differentiation.

Id1 overexpression in fetal liver cells. (A) Expansion of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells in vitro after retroviral transfection with an Id1 expression construct or a control (MIG) vector. (B) Relative expansion of Id1- or control vector-expressing fetal liver cells during 48-hours of culture under low (0.01 U/mL) erythropoietin conditions. Shown is the mean and SEM for 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*P < .05; see “Results” for details). (C) Representative FACS plots for ter119 and CD71 expression in lineage-negative fetal liver cells overexpressing Id1 or a control vector after 24 or 48 hours of in vitro culture. Bar charts indicating the proportion of cells at each of the 5 stages of erythroid differentiation (R1-R5) after 24 (D) and 48 hours (E) of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with Id1 expression or control constructs. Data (mean and SD) from a representative set of experiments performed in triplicate are shown.

Id1 overexpression in fetal liver cells. (A) Expansion of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells in vitro after retroviral transfection with an Id1 expression construct or a control (MIG) vector. (B) Relative expansion of Id1- or control vector-expressing fetal liver cells during 48-hours of culture under low (0.01 U/mL) erythropoietin conditions. Shown is the mean and SEM for 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*P < .05; see “Results” for details). (C) Representative FACS plots for ter119 and CD71 expression in lineage-negative fetal liver cells overexpressing Id1 or a control vector after 24 or 48 hours of in vitro culture. Bar charts indicating the proportion of cells at each of the 5 stages of erythroid differentiation (R1-R5) after 24 (D) and 48 hours (E) of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells retrovirally transfected with Id1 expression or control constructs. Data (mean and SD) from a representative set of experiments performed in triplicate are shown.

Id1 promotes erythroblast survival

Id1 is known to regulate cell cycle progression from G1- to S-phase in both mouse and human cell lines, through transcriptional regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors Cdkn1a (p21)40 and Cdkn1b (p27).41,42 However, Id1 knockdown had little effect on the cell cycle status of fetal liver progenitor cells cultured for 24 or 48 hours (Figure 5A-C), suggesting that Id1 does not contribute to erythroblast expansion by driving cell division. Moreover, Id1 knockdown had little effect on the expression of Cdkn1a (Figure 4D) and was associated with an approximately 50% decrease in Cdkn1b (p27) transcript levels after 48 hours of culture (Figure 5E). Together these results demonstrate that erythroblast expansion driven by Id1 does not reflect cell-cycle activation or negative regulation of p21 and/or p27 transcription.

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis after Id1 knockdown and overexpression in fetal liver cells. (A) Representative cell cycle profiles after 24 and 48 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or firefly luciferase. For clarity, the sub-G1 population representing apoptotic cells has been gated out, but see supplemental Figure 4 for analysis of the sub-G1 population. Bar charts summarizing cell cycle data (mean and SD) after 24 hours (B) and 48 hours (C) of culture from 1 of 2 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate and showing a similar result. Cdkn1a (D) and Cdkn1b (E) expression in lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells cultured in vitro for 24 or 48 hours. In each case, data are normalized relative to expression in cells transfected with the knockdown construct targeting firefly luciferase at the 24-hour time point. (F) Representative FACS plots for 7AAD and annexin V staining in lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase after 48 hours of culture. Early apoptotic cells stain annexin V positive, 7AAD negative (gated population in the figure). (G) Bar chart summarizing the relative number of early apoptotic cells after transfection with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase and 48 hours of in vitro culture. Summary data (mean and SEM) from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, are shown. Id1 knockdown is associated with a 2- to 4-fold increase in the proportion of early apoptotic cells (*P < .05; ***P < .001; see “Results” for details). (H) Bar chart summarizing the relative number of early apoptotic cells in lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells grown in low erythropoietin levels and overexpressing Id1. Data are normalized relative to the number of early apoptotic cells in control (MIG) transfected fetal liver cells (*P < .05; see “Results” for details).

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis after Id1 knockdown and overexpression in fetal liver cells. (A) Representative cell cycle profiles after 24 and 48 hours of in vitro culture of lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or firefly luciferase. For clarity, the sub-G1 population representing apoptotic cells has been gated out, but see supplemental Figure 4 for analysis of the sub-G1 population. Bar charts summarizing cell cycle data (mean and SD) after 24 hours (B) and 48 hours (C) of culture from 1 of 2 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate and showing a similar result. Cdkn1a (D) and Cdkn1b (E) expression in lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells cultured in vitro for 24 or 48 hours. In each case, data are normalized relative to expression in cells transfected with the knockdown construct targeting firefly luciferase at the 24-hour time point. (F) Representative FACS plots for 7AAD and annexin V staining in lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells transfected with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase after 48 hours of culture. Early apoptotic cells stain annexin V positive, 7AAD negative (gated population in the figure). (G) Bar chart summarizing the relative number of early apoptotic cells after transfection with knockdown constructs targeting Id1 or luciferase and 48 hours of in vitro culture. Summary data (mean and SEM) from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, are shown. Id1 knockdown is associated with a 2- to 4-fold increase in the proportion of early apoptotic cells (*P < .05; ***P < .001; see “Results” for details). (H) Bar chart summarizing the relative number of early apoptotic cells in lineage-negative E14.5 fetal liver cells grown in low erythropoietin levels and overexpressing Id1. Data are normalized relative to the number of early apoptotic cells in control (MIG) transfected fetal liver cells (*P < .05; see “Results” for details).

To investigate a possible role for Id1 in regulating cell survival, FACS analysis was used to assess annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin (7AAD) staining during fetal liver erythropoiesis. Compared with the control vector targeting firefly luciferase, Id1 knockdown was associated with a marked increase in the number of cultured erythroid cells undergoing apoptosis after 48 hours of culture (Figure 5F), suggesting that Id1 has an antiapoptotic function during terminal erythroid differentiation. The results of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate are summarized in Figure 5G and show that both knockdown constructs produced a significant increase in apoptotic cells at the 48-hour time point (Figure 5G; one-way repeated measures analysis of variance, n = 3, P < .01; Tukey posthoc analysis: control vs siRNA 1, P < .05; control vs siRNA 2, P < .001). Consistent with the increased annexin V staining, an increase in the size of the sub-G1 population, representing apoptotic cells,43 was seen at the 48-hour time point (supplemental Figure 4).

Overexpression of Id1 in erythroblasts cultured in standard (2 U/mL) erythropoietin concentrations led to a small but reproducible decrease in the rate of apoptosis after 48 hours of culture (data not shown), this largely reflecting the fact that the rate of apoptosis in cells transfected with the empty expression vector was low (typically < 5%) at both the 24-hour and the 48-hour time points. By contrast, when lineage-negative fetal liver cells were grown in low (0.01 U/mL) erythropoietin levels, control transfected cells demonstrated a marked increase in the rate of apoptosis at the 48-hour time point. At low erythropoietin concentrations, overexpression of Id1 was associated with a 3-fold decrease in the rate of apoptosis at the 48-hour time point compared with control (Figure 5H and supplemental Figure 5; Student t test, t = 5.99, P < .05) Taken together, these results suggest that Id1 promotes erythroblast survival and that this action is important in permitting rapid expansion of these cells during terminal differentiation.

Discussion

The discovery of JAK2V617F as an acquired mutation in the majority of PV patients and approximately 50% of essential thrombocythemia and idiopathic myelofibrosis patients represents an important landmark in the history of the MPDs.13,,–16 The V617F mutation leads to increased activation of at least 3 major signaling pathways: the JAK2-STAT5 pathway, the PI3K-pathway, and the ERK signaling pathway.14 Because of the ability of constitutively active forms of STAT5 to drive erythropoietin-independent erythroid colony formation44 and to give rise to a fatal MPD when overexpressed in hematopoietic stem cells,29 we decided to focus on downstream transcriptional targets of STAT5 as a means of further understanding the pathogenesis of the MPDs.

A genome-wide in silico search for conserved STAT5 consensus sequences identifies ID1 as a functionally important target in the erythroid lineage

We have shown previously that genome-wide computational screens for evolutionarily conserved transcription factor binding sites, coupled with subsequent functional validation, provide a powerful strategy for the identification of bona fide gene regulatory elements.37,45 In this paper, we have used this approach to identify ID1 as a novel transcriptional target of the JAK2-STAT5 signaling axis in erythroid cells and demonstrated that ID1 has a previously unrecognized prosurvival action during terminal erythroid differentiation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that ID1 expression is increased in JAK2V617F-positive erythroid colonies grown from patients with PV, suggesting that this antiapoptotic action of ID1 may be important in the pathogenesis of this disease.

A novel antiapoptotic function for Id1 in normal erythroid differentiation

The 4 mammalian Id proteins function as negative regulators of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors,33,46 a large family of both ubiquitously expressed and tissue-specific factors essential for the differentiation and maturation of a range of cell types. Because of the key role of bHLH proteins in driving lineage-specific differentiation, Id proteins have generally been thought of as negative regulators of differentiation, particularly at the early progenitor level. Accordingly, Id1 is known to be highly expressed in many immature cell types and is down-regulated with the onset of terminal differentiation.33 However, a role for Id1 during erythroid maturation, as suggested by increased expression of Id1 in ter119+ CD71+ cells, has not previously been identified.

Consistent with an important role for Id1 in ter119+CD71+ erythroblasts, Id1 knockdown during in vitro differentiation demonstrated a marked reduction in cell expansion between 24- and 48-hour time points, precisely at the time in which the majority of cells are passing through the ter119+ CD71+ stage of differentiation (Figure 3B-F). Furthermore, the reduction in the proportion of cells at the later stages of the differentiation process (population R4 in Figure 3D,F) after Id1 knockdown is also consistent with a stage-specific action of Id1 in ter119+CD71+ erythroblasts. Overexpression of Id1 in erythroblasts cultured in low erythropoietin levels was associated with a significant increase in erythroblast expansion but again also led to a decrease in the proportion of erythroblasts progressing to the final stages of terminal differentiation (Figure 4C,E). Although we have not investigated the action of Id1 overexpression on terminal differentiation in detail, this result suggests that although expression of Id1 in ter119+CD71+ erythroblasts is important in maintaining cell survival, subsequent down-regulation of Id1 is also necessary to permit terminal differentiation. This is consistent with work carried out by Lister et al, who demonstrated that overexpression of Id1 inhibits DMSO-induced differentiation of the MEL cell line,47 and with the known action of Id1 in other cellular systems.33

The mechanisms by which Id1 regulates erythroblast survival remain unclear and are the subject of ongoing work. As discussed previously, Id proteins are known to negatively regulate the action of bHLH transcription factors and, in this regard, the bHLH protein Tal1 is known to play a key role in erythropoiesis48 and has been demonstrated to form a complex with E2A, Gata1, Lmo2, and Ldb1 in the murine erythroblast cell line MEL.49 Like Tal1, Gata1 is essential for terminal erythroid differentiation beyond the proerythroblast stage50 and has an antiapoptotic action in erythroid progenitor cells.51 Thus one possible mechanism by which Id1 could regulate erythroblast cell survival is through the regulation of different complexes formed by Tal1 and/or Gata1.

STAT5, Id proteins, and the MPD phenotype

In addition to its role in terminal erythroid differentiation, Stat5 plays a role in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal and fate determination. Expression of a constitutively active form of Stat5a in murine embryonic stem cells enhances HSC self-renewal.52 Interestingly, Id1 has a similar effect on HSC self-renewal,34,35 thus raising the possibility that Id1 may be a downstream target of Stat5 in HSCs, as we have shown it to be in the erythroblast. Consistent with this, we have identified STAT5 binding to the Id1 +5.5 enhancer in human peripheral blood CD34+ cells (data not shown).

When overexpressed in human cord blood CD34+ cells, a constitutively active form of Stat5a skews the differentiation of myeloid progenitor cells toward the erythroid lineage,53 and overexpression of Id2 has a similar effect that is thought to be mediated through inhibition of the myeloid transcription factor Pu.1.54 Pu.1 is known to inhibit erythromegakaryocytic differentiation by inhibiting the action of the transcription factor Gata1. Thus by inhibiting Pu.1, Id2 increases Gata1 activity and promotes erythroid differentiation. It is not known whether ID1 shares the ability of Id2 to inhibit the action of Pu.1. However, Id1, Id2, and Id3 have all been demonstrated to bind Ets-type transcription factors.55 Thus, although speculative, this raises the possibility that Id1 may have a similar action to Id2 on erythroid differentiation and represent at least part of the mechanism by which Stat5 can enhance erythroid differentiation from common myeloid progenitor cells. Interestingly, retroviral overexpression of Jak2 containing one of the commonest of the exon 12 mutations, K539L, in our fetal liver assay led to further increases in Id1 expression, compared with overexpression of Jak2V617F (supplemental Figure 6). Given that patients with exon 12 mutations present with a more marked and isolated erythrocytosis and that exon 12 mutations are associated with a greater activation of downstream signaling pathways, including Stat5, compared with the V617F mutation,26 this further supports the suggestion that Id1 is transcriptionally regulated by the Jak2-Stat5 signaling axis and that Id1 plays a role in the erythrocytosis seen clinically in PV.

Taken together, these observations suggest the interesting possibility that Id1 may be a common target of Stat5 at multiple levels within the hematopoietic system (Figure 6) and may mediate several the actions of Stat5 relevant to the pathogenesis of the MPDs. This in turn would implicate Id1 as a potentially useful target for the development of novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of MPDs.

STAT5, ID proteins, and the MPD phenotype. Schematic illustration of erythrocyte formation from HSCs showing the various levels at which ID proteins act to enhance erythrocyte formation. HSC indicates hematopoietic stem cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor cell; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor cell; CFU-E, erythroid colony-forming unit; CFU-Mk, megakaryocyte colony-forming unit; I, ID1 enhances HSC self-renewal34,35 ; II, ID2 enhances myeloid differentiation over lymphoid differentiation54 ; III, ID2 enhances erythroid over megakaryocytic differentiation54 ; and IV, ID1 enhances erythroblast survival (this paper).

STAT5, ID proteins, and the MPD phenotype. Schematic illustration of erythrocyte formation from HSCs showing the various levels at which ID proteins act to enhance erythrocyte formation. HSC indicates hematopoietic stem cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor cell; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor cell; CFU-E, erythroid colony-forming unit; CFU-Mk, megakaryocyte colony-forming unit; I, ID1 enhances HSC self-renewal34,35 ; II, ID2 enhances myeloid differentiation over lymphoid differentiation54 ; III, ID2 enhances erythroid over megakaryocytic differentiation54 ; and IV, ID1 enhances erythroblast survival (this paper).

Tam et al have recently reported that ID1 expression is up-regulated in human cell lines expressing the BCR-ABL and FLT3-ITD oncogenes and that this up-regulation is reversed by inhibitors of these oncogenic tyrosine kinases.42 They also demonstrated that ID1 expression is increased in several gene expression datasets profiling patients with myeloid malignancies. Our demonstration that ID1 is directly regulated by the JAK2-STAT5 pathway in the erythroid system provides a direct link between an oncogenic tyrosine kinase and the transcriptional regulation of ID1. Given that constitutive activation of STAT5 is also a feature of both BCR-ABL–associated chronic myeloid leukemia and FLT3-ITD–associated acute myeloid leukemia, it is quite possible that STAT5 mediates the increased ID1 expression seen in these diseases. Interestingly, Tam et al identified an action of ID1 on cell-cycle regulation in the acute myeloid leukemia–derived MOLM-14 cell line. By contrast, we found no significant effect of Id1 on cell cycle progression in primary murine erythroblasts; rather Id1 levels seemed principally to regulate erythroblast survival. This difference may simply reflect a differing action of Id1 in erythroid and myeloid cell types, but it is equally possible that the antiapoptotic action of Id1 may not be observable in an immortalized cell line.

In conclusion, we identify a functionally important role for Id1 as a transcriptional target of the erythropoietin-Jak2-Stat5 signaling pathway in terminal erythroid differentiation. We show that Id1 promotes erythroblast survival and that ID1 expression is increased in Jak2V617F-positive erythroid colonies from patients with PV. Taken together, therefore, our data suggest that Id1 is a functionally important target of Stat5 both in normal erythropoiesis and in the MPDs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Jacinta Carter and Tina Hamilton for help with animal work, and Simon McCallum and Anna Petrunkina for help with flow cytometry.

Work in the authors' laboratories is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Center, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Cancer Research UK, and the Leukemia Research Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: A.D.W. designed experiments, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; E.C. performed experiments; I.J.D. contributed analytical tools; S.H. and K.A.B. analyzed data; M.A.D. performed research; D.M.-S. contributed analytical tools; H.F.L. designed experiments; and A.R.G. and B.G. designed experiments and reviewed the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Berthold Göttgens, Department of Hematology, Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, Addenbrookes' Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom; e-mail: bg200@cam.ac.uk.