In this issue of Blood, Comellas-Kirkerup and colleagues describe the course of 55 patients with laboratory criteria of the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) who displayed concurrent thrombocytopenia and/or autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA).1 None of these individuals had serologic or clinical features of lupus. This manuscript raises important questions concerning the relationship of cytopenias to the clinical events that comprise the Sapporo criteria for APS.2

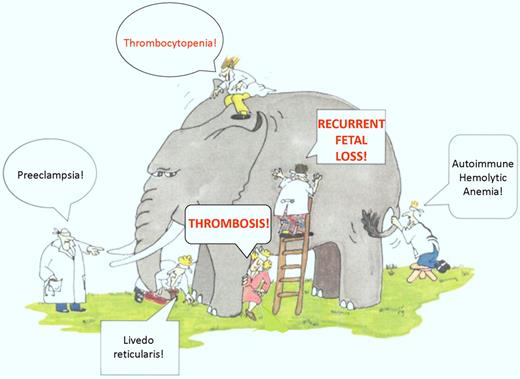

Defining the clinical manifestations of APS is somewhat reminiscent of the story of the blind men and the elephant, in which 5 blind men are asked to touch and then describe an elephant. Each man touches a different part of the elephant, ranging from the trunk to the tail, and reaches a different conclusion of what an elephant looks like (see figure). One interpretation of this parable is that people sometimes understand only a small portion of reality, from which they extrapolate broadly.

The APS elephant. A sampling of the many clinical manifestations seen in patients with APL, including the Sapporo diagnostic criteria of thrombosis and recurrent fetal loss. Many of these manifestations may be observed in clinical practice in patients with APL, although the strength of their relationship to the APS is uncertain. Thrombocytopenia is a particularly common finding in patients with APL, as demonstrated in the Comellas-Kirkerup study and other reports (adapted figure from Himmelfarb et al,11 Kidney International).

The APS elephant. A sampling of the many clinical manifestations seen in patients with APL, including the Sapporo diagnostic criteria of thrombosis and recurrent fetal loss. Many of these manifestations may be observed in clinical practice in patients with APL, although the strength of their relationship to the APS is uncertain. Thrombocytopenia is a particularly common finding in patients with APL, as demonstrated in the Comellas-Kirkerup study and other reports (adapted figure from Himmelfarb et al,11 Kidney International).

The reality of APS is that it is a “syndrome” in the true sense of the word, and despite important research advances, it remains a disorder for which we have limited understanding. Patients with APS experience clinical manifestations that range from uncommon events such as livedo reticularis, migraine headaches, chronic leg ulcers, cardiac valvular abnormalities, preeclampsia, and microangiopathic hemolytic syndromes, to the more common manifestations of thrombosis and recurrent fetal loss, which form the basis for the 2006 revised Sapporo diagnostic criteria.2 The relationship between the less common clinical events and antiphospholipid antibodies (APL) per se has not been felt to be sufficiently strong to include them in the relatively stringent Sapporo criteria. Yet, as clinicians we encounter these often enough to make us wonder whether we may really be like the blind men, discerning only a limited piece of the “APS elephant.”

The report of Comellas-Kirkerup and colleagues extends our knowledge concerning the “non-Sapporo criteria” manifestations of APS by describing the course of 55 patients with laboratory criteria of APS accompanied by thrombocytopenia and/or AIHA. Thrombocytopenia was present in 35 (64%) of these patients, while AIHA occurred in 14 (25%) and Evans syndrome in 6 (11%). A “clinical subgroup” of 25 patients displayed clinical manifestations of APS as defined by the Sapporo criteria over 13.2 years of follow-up, while a “nonclinical” subgroup of 30 patients did not over a median follow-up of only 5.4 years. The incidence of thrombocytopenia was similar in the clinical (51%) and nonclinical (48%) subgroups, while the incidence of AIHA was increased, though not statistically so, in the nonclinical subgroup. In the majority of patients, cytopenias were diagnosed either concurrently (16%) or after (60%) the clinical diagnosis of APS. However, in 24% of patients, cytopenias preceded the development of clinical criteria by 0.5 to 10 years. Lupus anticoagulants (LAC) occurred significantly more often in patients in the clinical subgroup, consistent with previous reports demonstrating that LAC correlate most strongly with clinical events, particularly thrombosis, in patients with APS.3 The frequency of LAC in patients with thrombocytopenia or Evans syndrome was also significantly higher in the clinical subgroup.

Although the clinical application of this report is limited by its retrospective design and the relatively small number of patients in the subgroups, it raises several interesting and important questions. First, given the frequency and impact of thrombocytopenia and AIHA in patients with APL, one might reasonably wonder whether these manifestations should be added to the Sapporo criteria. Thrombocytopenia, in particular, occurred with a high frequency in this study, and several other reports have identified a high incidence of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).4-6 Moreover, in some of the latter studies, the presence of APL in patients with ITP has correlated with the development of thrombosis,5,6 a manifestation of ITP that remains underappreciated. The fact that a substantial minority of patients with APL experienced cytopenias before manifesting Sapporo clinical APS criteria in the Comellas-Kirkerup study suggests that the presence of cytopenias might identify a subgroup of patients with APL who are at increased risk for thrombosis and/or fetal loss.

From a scientific perspective, the report of Comellas-Kirkerup raises the question of the specificity of the (presumed) autoantibodies responsible for the cytopenias. Although unactivated platelets are generally not thought to express significant amounts of anionic phospholipid on their surface, some evidence suggests that thrombocytopenia in patients with APL may result directly from phospholipid-reactive antibodies7 as well as nonphospholipid cross-reactive antibodies directed specifically against platelet glycoproteins.8 Others have demonstrated binding sites, such as GP1bα and apoER2′ that mediate binding of β2GPI to platelets, although the relationship of these interactions to the development of thrombocytopenia is uncertain.9 Even less information is available concerning interactions of APL or other autoantibodies with red cells.10 Finally, whether the clinical events that lead to a diagnosis of APS in patients with preexisting cytopenias and APL are associated with the appearance of new antibodies, or a change in antibody specificity (for example, reactivity with β2GPI domain 1), has not been determined.

The report of Comellas-Kirkerup provides new and important information concerning the relationship of cytopenias in patients with APL to the antiphospholipid syndrome, while reminding us that much additional work will be required to better understand the complex pathogenesis of this disorder. We have yet to wrap our arms around the “APS elephant.”

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

REFERENCES

National Institutes of Health