Abstract

Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) are important mediators of both innate and adaptive immunity against pathogens such as HIV. During the course of HIV infection, blood DC numbers fall substantially. In the present study, we sought to determine how early in HIV infection the reduction occurs and whether the remaining DC subsets maintain functional capacity. We find that both myeloid DC and plasmacytoid DC levels decline very early during acute HIV in-fection. Despite the initial reduction in numbers, those DCs that remain in circulation retain their function and are able to stimulate allogeneic T-cell responses, and up-regulate maturation markers plus produce cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with TLR7/8 agonists. Notably, DCs from HIV-infected subjects produced significantly higher levels of cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with TLR7/8 agonists than DCs from uninfected controls. Further examination of gene expression profiles indicated in vivo activation, either directly or indirectly, of DCs during HIV infection. Taken together, our data demonstrate that despite the reduction in circulating DC numbers, those that remain in the blood display hyperfunctionality and implicates a possible role for DCs in promoting chronic immune activation.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a critical role in the early host response to infection, mediating rapid antimicrobial effector functions and acting as potent antigen-presenting cells that stimulate adaptive immune responses.1 The 2 major subsets of DCs in blood, myeloid DCs (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), differ in morphology, phenotype and function. mDCs and pDCs express different but complementary Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which allow them to respond to different types of pathogens. mDCs recognize diverse pathogens due to their broad TLR expression and produce interleukin-12 (IL-12) after activation. pDCs specifically recognize pathogens containing ssRNA by TLR7 and unmethylated CpG DNA motifs via TLR9 and produce up to 1000-fold more interferonα (IFNα) than other types of blood cells in response to viruses.2

Reduced numbers of DC subsets are observed in the blood of subjects infected with HIV-1 (HIV).3 In chronic HIV infection, pDC levels are inversely correlated with plasma viral load,4 and the depletion of pDCs has been associated with HIV disease progression and development of opportunistic infections.5 It remains questionable whether antiretrovirals (ART) can restore DC numbers or enhance their properties.6,7 The functionality of DCs in HIV-infected people remains the subject of controversy. Several studies evaluating DC function from chronically infected HIV-subjects in response to in vitro stimulation with TLR agonists reported diminished responses,6,8 however these studies looked primarily at IFNα production from whole peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) populations as measured on a per-cell basis by indirect gating on pDCs within PBMCs and by comparing mean fluorescence intensity of intracellular IFNα staining. Hence the observed reduction in IFNα production may have been a consequence of the reduced frequency of pDCs in the blood.7 ART improved IFNα production by pDCs in response to TLR stimulation, but comparisons were not made to uninfected control pDCs.7

Both DC subsets are highly efficient at stimulating HIV-specific T-cell responses,9-11 and mDCs are capable of priming polyfunctional HIV-specific T-cell responses.12 Interestingly, mDCs do not become activated upon stimulation with HIV. In contrast, HIV directly stimulates pDCs likely through TLR713 to secrete large amounts of antiviral IFNα14-16 and inflammatory cytokines/chemokines that can lead to immune activation and a proapoptotic state. One study has shown that HIV-activated pDCs produce chemokines that recruit CD4+ T cells to fuel HIV expansion at local infection sites.17 Other studies assert that elevated and sustained type I IFN responses potentiate chronic immune activation and disease progression.18,19 IFNα produced by HIV-activated pDCs may contribute to generalized T-cell destruction through up-regulation of TRAIL and Fas/Fas ligand on infected and uninfected CD4+ T cells.20 As both DC subsets express the HIV receptor CD4 and coreceptors CCR5/CXCR4, they are also susceptible to infection by HIV.21,22 A recent in vitro study suggested that HIV preferentially infects DCs as compared with other cell types in the blood.23 Additionally, DCs possess the capacity to transfer HIV to T cells24 and lead to more robust viral production.

Because early interactions between DCs and HIV likely influence the development and maintenance of adaptive immune responses and viral control, we sought to investigate whether blood DC subsets were decreased during primary HIV infection (PHIV) and to determine whether their functionality was compromised. Understanding the pleiotropic effects of HIV on DCs in the earliest stages of infection is of importance to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this infection and could have significant implications for vaccine design and immunomodulatory therapeutic strategies targeting DCs.

Methods

Study population

The subjects enrolled in this cross-sectional and longitudinal study were recruited through New York University Center for AIDS Research (NYU CFAR) and CHAVI 012 (Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, New York, NY, and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) clinical sites. The majority of subjects donated blood for the cross-sectional and/or longitudinal evaluation of DC numbers, CD4 counts, and plasma viral loads (Table 1). Subjects who participated in the longitudinal evaluation of DC numbers were given the option to initiate ART at study entry or forgo initiation of ART until necessary. Samples were collected from all subjects on a monthly basis. Date of infection was estimated using the Serologic Testing Algorithm for Recent HIV Seroconversion (STARHS or detuned enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) to establish whether patients with positive HIV antibody tests had recently acquired HIV.25 Patients with a recent seroconversion of less than 170 days test positive using the highly sensitive commercially available HIV ELISA, but test negative using a less sensitive ELISA (detuned). A small number of subjects consented to undergo leukapheresis to allow for the collection of large numbers of PBMCs, from which blood DC subsets could be isolated for a more extensive analysis of DC function and gene expression profiles (Table 2). Cell numbers after flow cytometric sorting were the limiting factor and the major determinant of the number and type of analysis performed on each sample from each subject.

HIV-infected subjects were classified according to the PHIV staging system proposed by Fiebig et al.26 Stage I-II: HIV RNA positive and antibody negative within 14 days before study entry. Stage III-IV: HIV RNA positive, ELISA positive, and Western blot negative or indeterminate within 31-120 days before study entry. Stage V-VI: HIV RNA positive, ELISA positive, and Western blot positive within 31-120 days before study entry. None of the PHIV subjects were coinfected with hepatitis C virus (HCV). As controls, uninfected subjects (U, N = 14), high-risk but uninfected subjects (HR, N = 14), subjects with early established infection (E, N = 6), chronically infected subjects on therapy (CT, N = 9), chronically infected subjects not on therapy (CU, N = 9), and long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs, N = 14) were also studied. Of the 14 LTNPs, 6 were elite controllers (ECs). E subjects were defined as having been infected for longer than 1 year but less than 2 years. HR subjects were defined as men who have sex with men age-matched to the PHIV subjects who had engaged in risk behavior in the past 6 months. CU subjects were HIV-infected subjects who have been infected for more than 1 year but less than 5 years and never received ART. CT subjects were HIV-infected subjects who have been on ART for greater than 1 year. LTNP subjects were HIV-infected for greater than 10 years with detectable viremia, but not meeting CD4 criteria for ART. EC subjects were defined as having positive Western blot who maintained viral loads < 50 HIV RNA copies/mL in the absence of ART for more than 10 years. Although 6 of the 14 LTNP and EC recruited into the study had chronic HCV infection, there were no significant differences in both DC numbers between HIV-infected subjects with and without chronic HCV infection (data not shown).

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bellevue Hospital, New York University School of Medicine, the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, and CHAVI. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Enumeration of DC subsets in PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) from whole blood. PBMCs were stained with the following antibodies from BD Pharmingen: Lin1 fluorescein isothiocyanate, CD123 phycoerythrin, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR PerCP, and CD11c allophycocyanin, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences). At least 200 000 events were acquired for each sample using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), and data obtained were analyzed using FlowJo Version 8.8.3 software (TreeStar).

Isolation of blood DC subsets

DC subsets were enriched from leukaphereses using magnetic bead-based DC isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec). To further purify the DC subsets, the DC-enriched fraction was stained and sorted by flow cytometry (BD FACSAria) based on the absence of lineage markers (BD Pharmingen) and the high expression of CD4 (Invitrogen). mDCs express CD11c while pDCs do not express CD11c (BD Pharmingen). Purity (90%-99%) was typically achieved after flow cytometric sorting.

Stimulation of blood DC subsets with TLR agonists

Purified DCs were stimulated with 10μM R848 (3M Corporation) or 300 ng p24CA equivalents aldrithiol-2 (AT-2) HIVMN for 16-18 hours. AT-2–inactivated HIV-1 (AT-2 HIV) was prepared as described previously.27 AT-2 HIV lots used in this study included AT-2 HIV-1MN 3937 and 3934.

Mixed leukocyte reaction

Purified DCs were incubated with allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells negatively isolated from uninfected donors at a 1:30 DC–to–T cell ratio. After 5 days, 3H-thymidine (Amersham Biosciences) was added to the cultures, incubated overnight, harvested, and proliferation was assessed (MicroBeta; Perkin Elmer).

Cytokine/chemokine analysis

Supernatant levels of cytokines/chemokines were analyzed using a multiplex bead-based assay (Luminex; Bio-Rad). The presence of IFNα was detected using a multi-subtype IFNα ELISA kit (PBL Biomedical).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) and gene array

QPCR assays were done in triplicates using the SYBR Green I on a LightCycler apparatus (Roche Diagnostics). The following primer sequences were used: TLR7 forward primer, 5′-TCCAGTGTCTAAAGAACCTGG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-TGGTAAATATACCACACATCCC-3′; IRF7 forward primer, 5′-TCCCCACGC TATACCATCTACCT-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-ACAGCCAGGGTTCCAGCTT-3′; and GAPDH forward primer, 5′-GCAGGGGGGAGCCAAAAGGG-3′ and the reverse primer, 5′-TGCCAGCCCCAGCGTCAAAG-3′. Data were then collected using the AB 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed by comparative CT method using the SDS Version 1.3.1 Relative Quantification software.

Total RNA was isolated from DC subsets or whole PBMC (QIAGEN) and used to generate cDNA and cRNA to hybridize onto Human BeadChips (Illumina). Signal intensities were normalized to the mean intensity of all the genes represented on the array, and global scaling was applied before comparison analysis.

Statistical analysis

The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test (2-tailed) was used for the cross-sectional comparison of DC subset numbers within PBMC and data on stimulation of allogeneic T-cell proliferation and cytokine/chemokine production and up-regulation of maturation markers after stimulation of purified DC subsets with TLR agonists in groups of PHIV and control subjects (HIV-infected and uninfected) using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software). Adjustment for multiple comparisons of DC frequencies and numbers was done using the Benjamini and Hochberg method for controlling false discovery rates. The N values of Fiebig stage I-II (N = 2) and III-IV (N = 2-4) were too low for meaningful statistical analysis in the functional analyses of purified DC subsets. Therefore, statistical comparisons were only made between uninfected and Fiebig stage V-VI. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare gene expression results between PHIV and uninfected subjects for each DC subset and PBMCs from each subject. Spearman and linear regression analyses were used to describe correlations using R statistical software (http://www.r-project.org/) and Prism 4 (GraphPad Software). Linear spline–based mixed effects models were used to fit the longitudinal data and predict trends in values for each category using STATA Version 10.0 statistical software (Stata Corp LP). Log-transformed mDC numbers and pDC numbers were used in the mixed model analyses. In all cases, P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

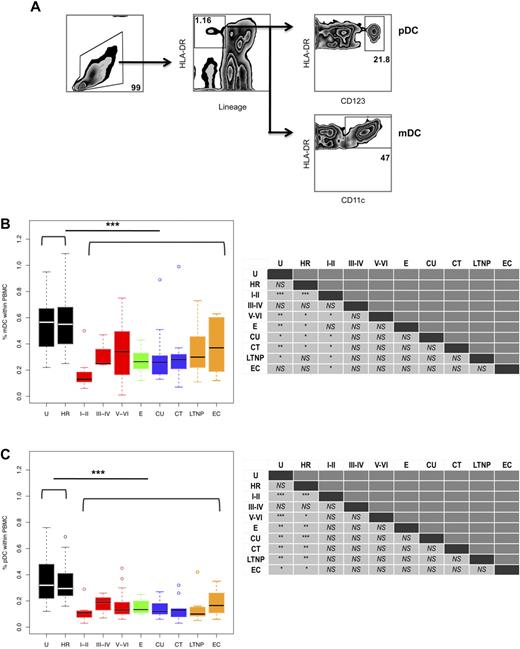

Peripheral blood DC numbers are significantly reduced in HIV-infected subjects

Previous studies have shown that peripheral blood DC numbers are reduced in early HIV infection, although the cause remains largely unknown. Our study sought to determine when the reduction in DC numbers occurs. We evaluated DC numbers in PHIV subjects who were in different stages of infection on study entry, as classified using the clinical staging proposed by Fiebig et al,26 and compared them to different cohorts of chronically HIV-infected subjects (Tables 1–2). Blood DC subsets were identified within the PBMC population based on the absence of lineage markers and expression of HLA-DR and CD11c for mDCs and CD123 for pDCs (Figure 1A).

mDC and pDC frequencies are significantly reduced during HIV infection. (A) The percentages of mDCs and pDCs were calculated based on the following gating scheme. Total viable PBMCs were gated based on their forward and side scatter (left panel). After 4-color staining with anti-lineage (CD3, CD14, CD16, CD20, and CD56) and anti-HLA-DR antibodies, mDCs and pDCs were identified as lineage negative and HLA-DR positive cells (middle panel). Additionally, pDCs expressed CD123 (right top panel), while mDCs expressed CD11c (right bottom panel). The percentages of (B) mDCs and (C) pDCs within PBMCs in the following groups of subjects are shown: U, uninfected; HR, high risk; primary infection: Fiebig stages I-II (N = 11), III-IV (N = 3), and V-VI (N = 27); E, early established infection (N = 6); CU, chronic/untreated (N = 9); CT, chronic/treated (N = 9); LTNP, long-term nonprogressor (N = 8); and EC, elite controller (N = 6). Horizontal bars indicate the median values. Hollow dots represent outliers. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine whether there were significant differences between subject groups in circulating DC frequencies and the results are summarized in the left panels. As indicated, DC frequencies in the HIV seronegative subjects (U plus HR groups) were significantly lower than those in all the HIV-infected subjects. The asterisks indicate P values: ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05; NS = not significant.

mDC and pDC frequencies are significantly reduced during HIV infection. (A) The percentages of mDCs and pDCs were calculated based on the following gating scheme. Total viable PBMCs were gated based on their forward and side scatter (left panel). After 4-color staining with anti-lineage (CD3, CD14, CD16, CD20, and CD56) and anti-HLA-DR antibodies, mDCs and pDCs were identified as lineage negative and HLA-DR positive cells (middle panel). Additionally, pDCs expressed CD123 (right top panel), while mDCs expressed CD11c (right bottom panel). The percentages of (B) mDCs and (C) pDCs within PBMCs in the following groups of subjects are shown: U, uninfected; HR, high risk; primary infection: Fiebig stages I-II (N = 11), III-IV (N = 3), and V-VI (N = 27); E, early established infection (N = 6); CU, chronic/untreated (N = 9); CT, chronic/treated (N = 9); LTNP, long-term nonprogressor (N = 8); and EC, elite controller (N = 6). Horizontal bars indicate the median values. Hollow dots represent outliers. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine whether there were significant differences between subject groups in circulating DC frequencies and the results are summarized in the left panels. As indicated, DC frequencies in the HIV seronegative subjects (U plus HR groups) were significantly lower than those in all the HIV-infected subjects. The asterisks indicate P values: ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05; NS = not significant.

Comparison of DC frequencies in all the HIV-infected subjects (those at Fiebig stage I-II, III-IV, and V-VI and E, CT, CU, LTNPs, and ECs) to those in the uninfected (U plus HR) groups revealed that HIV infection results in a significant overall reduction in the percentage of mDCs (median 0.27% vs 0.56%, P < .001; Figure 1B) and pDCs (median 0.13% vs 0.31%, P < .001; Figure 1C) within the PBMC pool. Likewise, a significant reduction was also observed in all the HIV-infected subjects when absolute numbers of circulating mDCs (median 5.4 cells/μL blood vs 11.0 cells/μL blood, P < .001; supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and pDCs (median 2.6 cells/μL blood vs 6.1 cells/μL blood, P < .001; supplemental Figure 1B) were compared with those in all the uninfected (U plus HR) subjects. Of note, we did not detect significant differences between uninfected (U plus HR) groups and between women and men in both DC subset numbers (data not shown).

Using this clinical staging system, we found that the reductions in both DC subsets were evident very early, at Fiebig stages I-II (Figure 1B-C and supplemental Figure 1A-B). In the absence of treatment, DC subset frequencies and numbers appeared to increase slightly in the later stages of acute infection at Fiebig stages V-VI, although the numbers failed to reach the same levels observed in the uninfected (U plus HR) groups. After adjustment for multiple comparisons, we found that mDC frequencies and numbers at Fiebig stage I-II compared with uninfected (U and HR), and pDC frequencies and numbers at Fiebig stage I-II and V-VI, and E, CU, CT, and LTNP were significantly reduced compared with uninfected (U and HR) (supplemental Tables 1-2).

In accordance with previous studies,6,28,29 we found that circu-lating DC frequencies and numbers in subjects chronically infected with HIV, both ART-treated and untreated, were significantly reduced compared with uninfected (U plus HR) subjects (Figure 1B-C and supplemental Figure 1A-B). We did not find significant differences in circulating DC frequencies or numbers between chronic subjects that were ART-treated and untreated. Our findings that circulating DC frequencies in LTNPs were significantly lower than those in uninfected (U plus HR) subjects are in contrast to previous reports that showed elevated DC numbers in LTNPs.5,30 Surprisingly, the number of circulating DCs of both subsets was also reduced in ECs compared with uninfected (U plus HR) subjects.

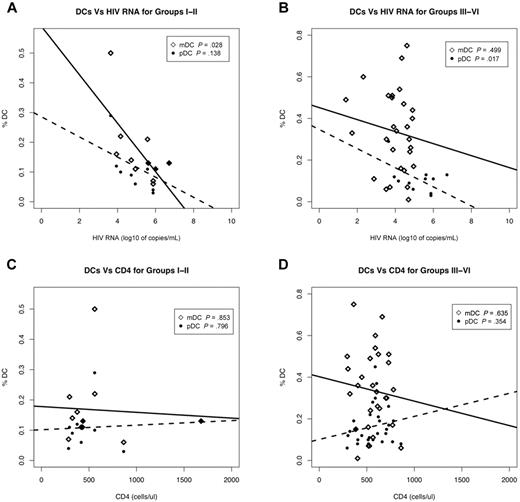

DC frequencies are strongly associated with plasma viral load

The observation that DC numbers are reduced in ECs and chronic HIV-infected subjects on therapy suggests that even in the presence of clinically undetectable levels of viremia (< 50 HIV RNA copies/mL) the number of circulating mDCs and pDCs is affected during HIV infection. Given this, we sought to determine whether the reduction in circulating DC numbers correlated with plasma viral load or CD4 counts. To facilitate analysis, PHIV subjects were grouped to differentiate the Fiebig stages when the detectable adaptive immune response, that is, antibody response (ELISA), has been initiated. Therefore, subjects at Fiebig stages I-II were grouped separately from those at Fiebig stages III-VI.

We observed a significant negative correlation between mDC frequencies and plasma viral load in HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stage I-II (P = .028) but not in subjects at the later Fiebig stages III-VI (P = .499; Figure 2A-B). On the other hand, pDC frequencies of subjects in Fiebig stages III-VI were negatively correlated with plasma viral load (P = .017) but not at Fiebig stages I-II (P = .136; Figure 2A-B). Our observation that mDC frequencies negatively correlated with plasma viral loads during the early Fiebig stages (I-II), while the negative correlation between pDC frequencies and plasma viral load occurred at the later Fiebig stages (III-VI), suggests that the effects of HIV on the DC subtypes may be independent of each other.

DC frequencies are strongly associated with plasma viral load. Correlation of plasma viral load (A-B) and CD4 counts (C-D) to mDC and pDC frequencies from primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-II (N = 11) (A,C) and III-VI (N = 30) (B,D). III-IV (N = 3) and V-VI (N = 27) were combined as III-IV contained too few N for statistical analysis. Associations between various parameters were evaluated using linear regression. Open diamonds correspond to mDCs and closed circles correspond to pDCs. Solid lines denote the relationship between mDC numbers and plasma viral load or CD4 counts. Dotted lines denote the relationship between pDC numbers and plasma viral load or CD4 counts. p denotes the P value of the slope parameter in the linear regression.

DC frequencies are strongly associated with plasma viral load. Correlation of plasma viral load (A-B) and CD4 counts (C-D) to mDC and pDC frequencies from primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-II (N = 11) (A,C) and III-VI (N = 30) (B,D). III-IV (N = 3) and V-VI (N = 27) were combined as III-IV contained too few N for statistical analysis. Associations between various parameters were evaluated using linear regression. Open diamonds correspond to mDCs and closed circles correspond to pDCs. Solid lines denote the relationship between mDC numbers and plasma viral load or CD4 counts. Dotted lines denote the relationship between pDC numbers and plasma viral load or CD4 counts. p denotes the P value of the slope parameter in the linear regression.

We did not observe significant correlations between mDC or pDC frequencies and CD4 counts from HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-II and III-VI (Figure 2C-D). Additionally, there was no significant correlation between plasma viral load and CD4 counts at all the Fiebig stages I-II (P = .149) and III-VI (P = .387; data not shown).

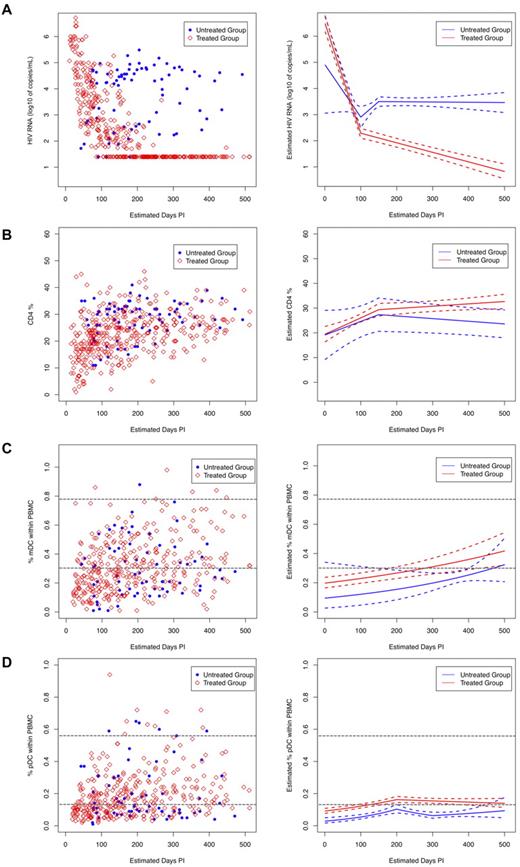

Longitudinal variability in DC subset frequencies

Analysis of treated subjects revealed that viral loads decreased significantly (Figure 3A; P < .001) at a rate of 0.042 log10 copies/mL/d over the first 100 days of treatment and then decreased more slowly, at a rate of 0.004 log10 copies/mL/d, which was maintained for the next 100 days. On the contrary, although viral loads in the untreated subjects also decreased initially, they then began to increase after 100 days of follow-up at a rate of 0.012 log10 copies/mL/d. However, after 150 days, their viral loads started to decrease at a rate of 0.01 log10 copies/mL/d (Figure 3A). Overall, the treated group had significantly lower HIV viral loads than the untreated group, after being on treatment for 50 days.

Longitudinal measurements of plasma viral load, CD4 cell, and DC numbers in HIV-infected subjects. HIV-infected subjects enrolled in the study were grouped as treated (N = 40, red open diamonds) and untreated (N = 13, blue solid circles) and were followed longitudinally for 52 weeks. Date of infection was estimated for all subjects using the Serologic Testing Algorithm for Recent HIV Seroconversion (STARHS or detuned ELISA) to establish whether patients with positive HIV antibody tests had recently acquired HIV.25 All monthly sample collection points were aligned accordingly. Left panels show measurements of (A) plasma viral load, (B) percent CD4, and (C) percent mDC, and (D) percent pDC frequencies obtained during the monthly visits. Right panels show the trend for each subject group (solid lines: red = ART treated and blue = untreated) as calculated using linear spline mixed effects models, and the dashed lines around the group average estimates represent the 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal gray dashed lines indicate the range of DC numbers observed in uninfected controls.

Longitudinal measurements of plasma viral load, CD4 cell, and DC numbers in HIV-infected subjects. HIV-infected subjects enrolled in the study were grouped as treated (N = 40, red open diamonds) and untreated (N = 13, blue solid circles) and were followed longitudinally for 52 weeks. Date of infection was estimated for all subjects using the Serologic Testing Algorithm for Recent HIV Seroconversion (STARHS or detuned ELISA) to establish whether patients with positive HIV antibody tests had recently acquired HIV.25 All monthly sample collection points were aligned accordingly. Left panels show measurements of (A) plasma viral load, (B) percent CD4, and (C) percent mDC, and (D) percent pDC frequencies obtained during the monthly visits. Right panels show the trend for each subject group (solid lines: red = ART treated and blue = untreated) as calculated using linear spline mixed effects models, and the dashed lines around the group average estimates represent the 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal gray dashed lines indicate the range of DC numbers observed in uninfected controls.

The CD4 counts of both treated and untreated subjects increased significantly during the initial 150 days postinfection, although the rate of increase in CD4 counts of the treated subjects was higher than that of the untreated subjects (Figure 3B; 0.07 cells/d vs 0.05 cells/d). After 150 days postinfection, the 2 groups diverged. The rate of increase in the CD4 counts of the treated subjects decreased (0.07 cells/d to 0.01 cells/d), whereas the CD4 counts of the untreated subjects showed a decreasing pattern that became significant over time (Figure 3B). Although CD4 counts increased in both treated and untreated groups in the initial days after infection, the absence of treatment led to an eventual decline in CD4 counts.

Circulating mDC frequencies exhibited a significant increasing trend over time for both the treated and untreated group at a rate of 0.001 log10 %DC/d (treated: P = .001 and untreated: P = .002; Figure 3C). The mDC frequencies of both treated and untreated subjects did not appear to be significantly different (Figure 3C; P = .081), possibly indicating no direct effect of circulating virus on mDC numbers. In contrast, mDC frequencies from uninfected subjects did not change significantly over time (P = .238; data not shown) and were higher than mDC frequencies in both treated and untreated groups (data not shown).

Analysis of the circulating pDC frequencies revealed that they increased significantly in both treated (P = .001) and untreated (P = .002) subjects within the initial 200 days postinfection, although at different rates (Figure 3D). After 200 days, the rate of increase in pDC frequencies of the treated group declined, while the pDC frequencies dropped in the untreated group and then slowly increased after 300 days, possibly indicating a more direct effect of circulating virus on pDC frequencies. Treatment appeared to stabilize pDC frequencies as the overall pDC frequencies in the treated group were significantly higher than those in the untreated group, especially after 120 days of treatment (Figure 3D; P = .011). In contrast, pDC frequencies in the uninfected subjects did not change significantly over time (P = .618; data not shown) and remained higher than those of the treated and untreated HIV-infected subjects (data not shown).

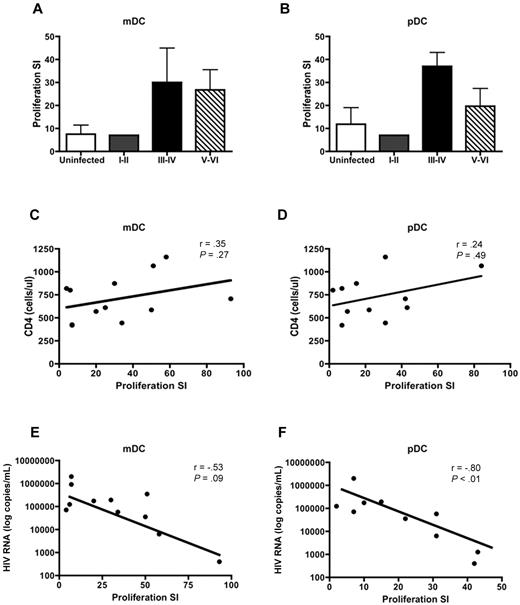

DC subsets from PHIV subjects stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to proliferate

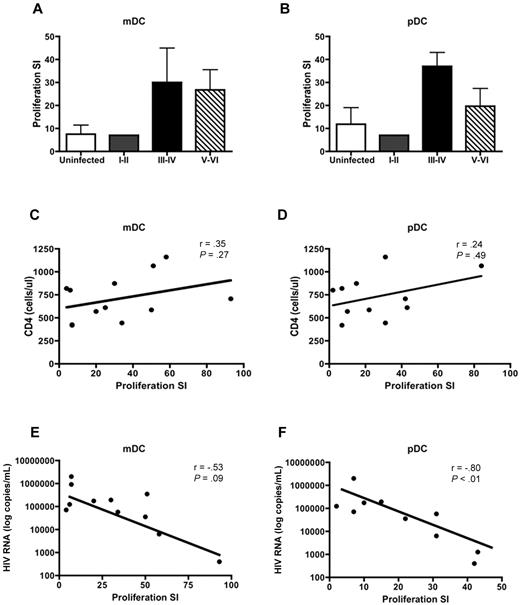

DCs are potent stimulators of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation. Therefore, we sought to determine whether HIV infection altered the ability of DCs to stimulate T-cell proliferation. DCs were isolated from PHIV subjects and cocultured with PBMCs depleted of antigen-presenting cells from uninfected subjects. As expected, mDCs (Figure 4A) and pDCs (Figure 4B) from uninfected subjects were potent stimulators of allogeneic T cells with the pDCs being slightly better at stimulating T cells compared with mDCs with a mean proliferation stimulation index (SI) of 11.9 (pDC) versus 7.5 (mDC).

mDCs and pDCs from PHIV subjects stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. mDCs and pDCs purified from HIV-seronegative subjects or people with primary HIV infection were cultured with PBMCs depleted of antigen-presenting cells from uninfected subjects. Proliferation was evaluated at day 5 by measurement of 3H-thymidine incorporation and was expressed as a SI. The SI was determined by dividing the proliferation induced in the presence of DCs by the proliferation observed in a culture with no DCs added. The mean T-cell proliferation induced by (A) mDCs and (B) pDCs is shown from uninfected subjects (N = 5, □) and subjects at Fiebig stages I-II (N = 1, ), III-IV (N = 2, ■), and V-VI (N = 9,▧). The panels below show the correlation of (C-E) mDC-induced and (D-F) pDC-induced T-cell proliferation to (C-D) CD4 counts and (E-F) plasma viral load in all the HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using a Spearman correlation.

), III-IV (N = 2, ■), and V-VI (N = 9,▧). The panels below show the correlation of (C-E) mDC-induced and (D-F) pDC-induced T-cell proliferation to (C-D) CD4 counts and (E-F) plasma viral load in all the HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using a Spearman correlation.

mDCs and pDCs from PHIV subjects stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. mDCs and pDCs purified from HIV-seronegative subjects or people with primary HIV infection were cultured with PBMCs depleted of antigen-presenting cells from uninfected subjects. Proliferation was evaluated at day 5 by measurement of 3H-thymidine incorporation and was expressed as a SI. The SI was determined by dividing the proliferation induced in the presence of DCs by the proliferation observed in a culture with no DCs added. The mean T-cell proliferation induced by (A) mDCs and (B) pDCs is shown from uninfected subjects (N = 5, □) and subjects at Fiebig stages I-II (N = 1, ), III-IV (N = 2, ■), and V-VI (N = 9,▧). The panels below show the correlation of (C-E) mDC-induced and (D-F) pDC-induced T-cell proliferation to (C-D) CD4 counts and (E-F) plasma viral load in all the HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using a Spearman correlation.

), III-IV (N = 2, ■), and V-VI (N = 9,▧). The panels below show the correlation of (C-E) mDC-induced and (D-F) pDC-induced T-cell proliferation to (C-D) CD4 counts and (E-F) plasma viral load in all the HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using a Spearman correlation.

Allogeneic T cells stimulated by DC subsets from PHIV subjects exhibited higher levels of proliferation, albeit not statistically significant, compared with uninfected subjects. The mean proliferation SI for assays using mDCs isolated from subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI was 26.8 (range: 1-93) compared with 7.5 (range: 1-19) for uninfected subjects (P = .38). The mean proliferation SI for assays using pDCs isolated from subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI was 19.7 (range: 1-84) compared with 11.9 (range: 1-33) for uninfected subjects (P = .04; Figure 4A-B).

We did not find a correlation between CD4 counts and proliferation SI for either mDCs (Figure 4C) or pDCs (Figure 4D). However there was a strong negative correlation between plasma viral load and proliferation SI for pDCs (r = −0.80, P < .01; Figure 4F) but not mDCs (r = −0.53, P = .09; Figure 4E).

Our findings suggest that the presence of high levels of virus can negatively influence the ability of pDC to stimulate T cells, perhaps through HIV-induced regulatory T-cell formation.31 Therefore, although the ability to stimulate T cells is not reduced during the later stages of PHIV, the prolonged exposure of mDCs and pDCs to circulating HIV may eventually lead to impairment in stimulatory capacity.

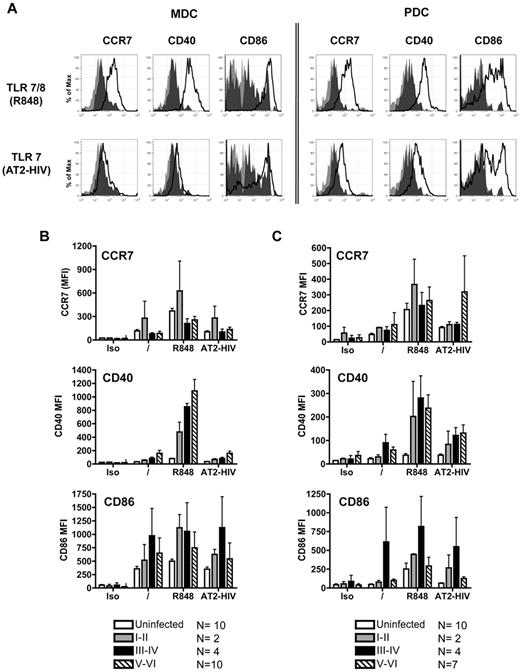

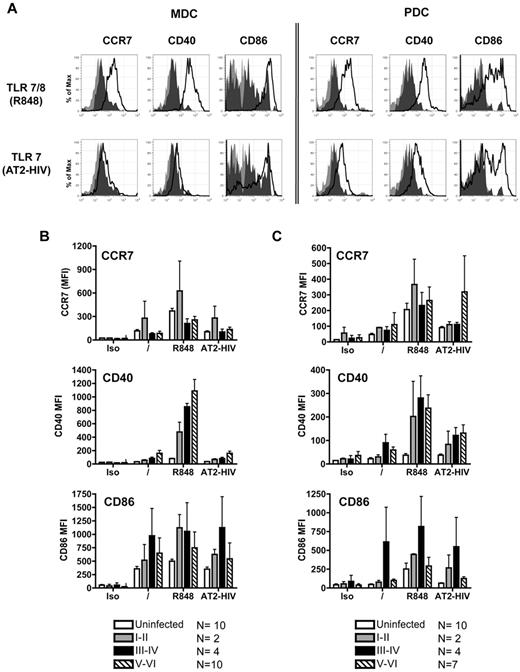

DC subsets induce expression of maturation markers in response to stimulation with TLR agonists

We evaluated the up-regulation of CD40, CD86, and CCR7 on DC subsets in response to stimulation with the TLR7/8 agonists R848 and AT-2 HIV.13 Overnight incubation of unstimulated mDCs isolated from uninfected donors resulted in a spontaneous increase in expression of CCR7, CD40, and CD86 (data not shown), which was further enhanced upon stimulation with R848 but not AT-2 HIV (data not shown). pDCs isolated from uninfected subjects up-regulated CCR7, CD40, and CD86 in response to R848 and AT-2 HIV. pDCs stimulated with R848 induced higher levels of expression of CCR7 and CD86 compared with those stimulated with AT-2 HIV (data not shown).

Similar to DC subsets from uninfected subjects, overnight stimulation of purified mDCs and pDCs (Figure 5A) from PHIV subjects with TLR agonists resulted in the up-regulation of CD40, CD86, and CCR7. mDCs purified from subjects at all Fiebig stages up-regulated CCR7 and CD40 in response to R848 but not to AT2-HIV (Figure 5B). pDCs purified from subjects at all Fiebig stages up-regulated CCR7, CD40, and CD86 in response to R848 and AT2-HIV (Figure 5C). Of note, higher expression of CCR7, CD40, and CD86 was induced on DC subsets from the PHIV subjects stimulated with TLR agonists compared with uninfected subjects but differences were not statistically significant. Thus both mDCs and pDCs from PHIV subjects retained their capacity to up-regulate CCR7, required for migration to lymph nodes, and CD40 and CD86, involved in interaction with T cells.

DCs up-regulate maturation markers in response to stimulation with TLR agonists. Purified mDCs and pDCs were stimulated with the following TLR7 agonists: 10μM R848 and 300 ng of p24CA equivalents AT-2 HIV for 16-18 hours. Cells were harvested and stained for expression of CCR7, CD40, and CD86. (A) Representative flow cytometric data from primary HIV-infected subject at Fiebig stages I-II. Light gray shading denotes staining of the unstimulated cells with isotype control antibodies. Dark gray shading denotes antibody staining of the unstimulated cells. Solid black lines denote antibody staining of the stimulated cells. Summary of (B) mDC and (C) pDC expression of CCR7, CD40, and CD86 after TLR stimulation. Each bar represents the mean staining (expressed as mean fluorescence intensity; MFI) of DCs from uninfected subjects, subjects at Fiebig stages I-II, subjects at Fiebig stages III-IV, and subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

DCs up-regulate maturation markers in response to stimulation with TLR agonists. Purified mDCs and pDCs were stimulated with the following TLR7 agonists: 10μM R848 and 300 ng of p24CA equivalents AT-2 HIV for 16-18 hours. Cells were harvested and stained for expression of CCR7, CD40, and CD86. (A) Representative flow cytometric data from primary HIV-infected subject at Fiebig stages I-II. Light gray shading denotes staining of the unstimulated cells with isotype control antibodies. Dark gray shading denotes antibody staining of the unstimulated cells. Solid black lines denote antibody staining of the stimulated cells. Summary of (B) mDC and (C) pDC expression of CCR7, CD40, and CD86 after TLR stimulation. Each bar represents the mean staining (expressed as mean fluorescence intensity; MFI) of DCs from uninfected subjects, subjects at Fiebig stages I-II, subjects at Fiebig stages III-IV, and subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

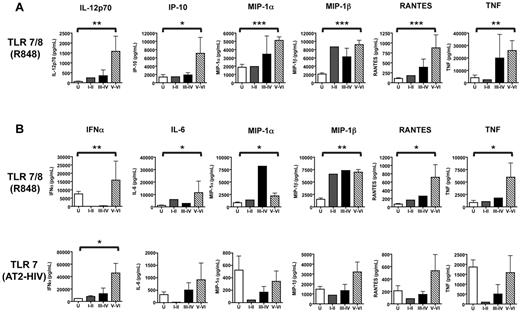

DC subsets from PHIV subjects are hyperresponsive to TLR7 agonists and produce high levels of cytokines/chemokines on stimulation

mDCs and pDCs from uninfected subjects secreted measurable amounts of the following cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with R848: IL-6, tumor necrosis factorα (TNFα), inducible protein (IP)-10, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP1α), MIP1β, and regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES). In addition, mDCs (but not pDCs) produced IL-12p70, while IFNα was produced specifically by pDCs. pDCs also produced the same analytes in response to stimulation with AT-2 HIV, albeit at lower levels (Figure 6A-B). In agreement with a previous study by our laboratory,14 mDCs did not produce measurable levels of cytokines/chemokines in response to AT-2 HIV (data not shown) as HIV directly activates pDCs but not mDCs.

Levels of chemokines and cytokines produced by DCs in response to stimulation with TLR7 agonists. Purified mDCs and pDCs were stimulated with 10μM R848 or 300 ng of p24CA equivalents AT-2 HIV for 16-18 hours. Supernatants were collected, and cytokine and chemokine production was evaluated using a multiplex bead-based assay (Luminex) and an IFNα ELISA. (A) Summary of cytokines and chemokines secreted by mDCs in response to stimulation with 10μM R848. (B) Summary of cytokines and chemokines secreted by pDCs in response to stimulation with 10μM R848 or 300 ng of p24CA equivalents AT-2 HIV. Each bar represents the median analyte level (pg/mL) produced by DCs from uninfected subjects (N = 10, □), subjects at Fiebig stages I-II (N = 2, ), subjects at Fiebig stages III-IV (N = 4, ■), and subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI (N = 10 for mDCs, 7 for pDCs,▧). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in the levels of analyte production by DCs from primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI and uninfected controls. The asterisks indicate P values: ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05.

), subjects at Fiebig stages III-IV (N = 4, ■), and subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI (N = 10 for mDCs, 7 for pDCs,▧). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in the levels of analyte production by DCs from primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI and uninfected controls. The asterisks indicate P values: ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05.

Levels of chemokines and cytokines produced by DCs in response to stimulation with TLR7 agonists. Purified mDCs and pDCs were stimulated with 10μM R848 or 300 ng of p24CA equivalents AT-2 HIV for 16-18 hours. Supernatants were collected, and cytokine and chemokine production was evaluated using a multiplex bead-based assay (Luminex) and an IFNα ELISA. (A) Summary of cytokines and chemokines secreted by mDCs in response to stimulation with 10μM R848. (B) Summary of cytokines and chemokines secreted by pDCs in response to stimulation with 10μM R848 or 300 ng of p24CA equivalents AT-2 HIV. Each bar represents the median analyte level (pg/mL) produced by DCs from uninfected subjects (N = 10, □), subjects at Fiebig stages I-II (N = 2, ), subjects at Fiebig stages III-IV (N = 4, ■), and subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI (N = 10 for mDCs, 7 for pDCs,▧). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in the levels of analyte production by DCs from primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI and uninfected controls. The asterisks indicate P values: ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05.

), subjects at Fiebig stages III-IV (N = 4, ■), and subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI (N = 10 for mDCs, 7 for pDCs,▧). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in the levels of analyte production by DCs from primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI and uninfected controls. The asterisks indicate P values: ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05.

DC subsets from PHIV subjects produced a similar pattern of cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with TLR7 agonists. Remarkably, both mDCs and pDCs had higher propensity for cytokine production in response to R848 compared with DC subsets from uninfected subjects. mDCs from Fiebig stage V-VI subjects produced significantly higher levels of IL-6, TNFα, IP-10, MIP1α, MIP1β, RANTES, and IL-12p70 (Figure 6A), while pDC produced significantly higher levels of IFNα, IL-6, TNFα, MIP1α, MIP1β, and RANTES in response to R848 (Figure 6B). pDCs from primary HIV-infected subjects also produced cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with AT-2 HIV. With the exception of IFNα, levels of analyte production were generally lower than elicited in response to stimulation with R848. Of note, IFNα production by pDCs from PHIV subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI in response to stimulation with AT-2 HIV was significantly higher than that produced by pDCs from uninfected subjects (Figure 6B). The higher propensity for cytokine production by DC subsets from PHIV subjects suggests that HIV infection induces a hyperresponsive state in DCs.

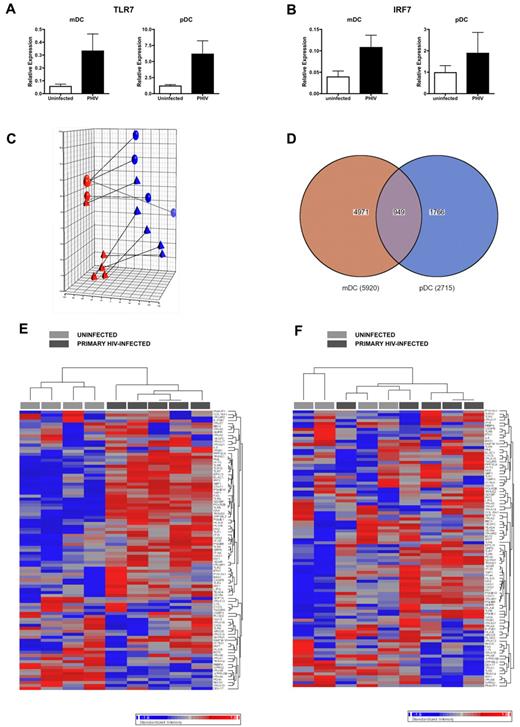

DC subsets from PHIV subjects express elevated levels of TLRs and their downstream signaling components

Our observations that DC subsets from PHIV subjects produced increased amounts of cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with TLR7 agonists prompted us to investigate changes in baseline expression of genes related to cytokine signaling in DC subsets. We sought to evaluate the expression of TLRs and their downstream signaling components as increased expression could explain the enhanced sensitivity to stimulation with TLR7 agonists.

We first evaluated the expression levels of TLR7 and IRF7 in DCs from 5 PHIV subjects. QPCR analysis of the expression of TLR7 (Figure 7A) and IRF7 (Figure 7B) revealed that these genes were present at higher levels in ex vivo mDCs and pDCs from PHIV subjects compared with uninfected subjects, likely explaining their enhanced sensitivity to stimulation with TLR7 agonists.

DCs display a transcriptional profile that is indicative of in vivo activation. (A-B) RNA was extracted from ex vivo purified mDCs and pDCs from uninfected and primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI and converted to cDNA. QPCR was conducted using primers for TLR7 (A) and IRF 7 (B). Expression levels were normalized using GAPDH. The mean relative gene expression levels in mDCs and pDCs from uninfected subjects (N = 5, □) and subjects with primary HIV infection (N = 5 subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI, ■) are shown. (C-F) RNA was extracted from ex vivo purified mDCs and pDCs and hybridized on Illumina Human HT-12 Expression Beadchips, which assays approximately 25 000 annotated genes with > 48 000 probes derived from the RefSeq (Build 36.2, Rel 22) and the UniGene (Build 99) databases. Comparisons of expression results were done in the Partek software using ANOVA. (C) PCA of complete gene expression profiles measured on each individual array. PCA was performed on log2 transformed and quantile normalized expression data. Each colored sphere (primary HIV-infected) and triangle (uninfected) indicates complete expression profiles of individual samples with similarity between data sets displayed as proximity in 3-dimensional space (red = mDC, blue = pDC). The lines connect samples from the same subject. (D) Venn diagram indicating overlap of probe sets with differential expression in mDCs and pDCs from primary HIV-infected subjects compared with uninfected subjects as calculated using ANOVA. (E-F) Heat map of probe sets associated with immune activation in mDCs (E) and pDCs (F). Each column represents different subjects: uninfected (N = 4, light gray) and primary HIV-infected (N = 5, dark gray). Genes that are down-regulated by up to 2-fold are blue, and genes that are up-regulated by up to 2-fold are red.

DCs display a transcriptional profile that is indicative of in vivo activation. (A-B) RNA was extracted from ex vivo purified mDCs and pDCs from uninfected and primary HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI and converted to cDNA. QPCR was conducted using primers for TLR7 (A) and IRF 7 (B). Expression levels were normalized using GAPDH. The mean relative gene expression levels in mDCs and pDCs from uninfected subjects (N = 5, □) and subjects with primary HIV infection (N = 5 subjects at Fiebig stages V-VI, ■) are shown. (C-F) RNA was extracted from ex vivo purified mDCs and pDCs and hybridized on Illumina Human HT-12 Expression Beadchips, which assays approximately 25 000 annotated genes with > 48 000 probes derived from the RefSeq (Build 36.2, Rel 22) and the UniGene (Build 99) databases. Comparisons of expression results were done in the Partek software using ANOVA. (C) PCA of complete gene expression profiles measured on each individual array. PCA was performed on log2 transformed and quantile normalized expression data. Each colored sphere (primary HIV-infected) and triangle (uninfected) indicates complete expression profiles of individual samples with similarity between data sets displayed as proximity in 3-dimensional space (red = mDC, blue = pDC). The lines connect samples from the same subject. (D) Venn diagram indicating overlap of probe sets with differential expression in mDCs and pDCs from primary HIV-infected subjects compared with uninfected subjects as calculated using ANOVA. (E-F) Heat map of probe sets associated with immune activation in mDCs (E) and pDCs (F). Each column represents different subjects: uninfected (N = 4, light gray) and primary HIV-infected (N = 5, dark gray). Genes that are down-regulated by up to 2-fold are blue, and genes that are up-regulated by up to 2-fold are red.

We next determined whether the up-regulation of TLR7 was indicative of overall immune activation, as reported to be associated with HIV infection. We found enrichment of interferon-stimulated genes as well as the up-regulation of TLR7 in PBMCs from PHIV subjects (supplemental Figure 2). We then conducted gene expression analysis of ex vivo DC subsets. Principal component analysis (PCA) of ex vivo DC subsets from uninfected and PHIV subjects revealed that DCs from PHIV subjects exhibited a transcriptional profile that was clearly distinct from that of DCs from uninfected subjects, thereby indicating that HIV infection had altered gene expression in circulating DC subsets (Figure 7C) despite there being no evidence of direct infection of these cells (data not shown). Comparative analysis of gene expression using ANOVA in DC subsets from PHIV and uninfected subjects revealed that 5920 probes were nominally significantly different in mDCs (P < .05), 2715 probes were nominally significantly different in pDCs (P < .05), and 949 of these were differentially expressed in both DC subsets (P < .05; Figure 7D). Although the differences in gene expression between PHIV and uninfected DCs were generally subtle, there were several immune-related genes whose expression was distinctly different between DC subsets from uninfected and PHIV subjects (Figure 7E-F). However, at a setting of a 5% false discovery rate, only mDCs contained genes that were significantly different in expression between uninfected and PHIV subjects. Genes (292) were expressed at significantly different levels in mDCs from uninfected and PHIV subjects. Analysis of these 292 genes revealed the up-regulation of HIV-infection, immune, apoptosis, cell-cycle, transcription/translation, and intracellular trafficking genes (Table 3). The up-regulation of these genes suggests the activation of mDCs in vivo during PHIV. The lack of genes that were significantly different in pDCs from uninfected and PHIV subjects was surprising, but may be a consequence of the fact that pDCs are directly activated by HIV14 and therefore, those activated in vivo may no longer be in circulation.

Discussion

This study evaluated peripheral blood DC numbers, phenotype, and function in PHIV subjects using cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Despite reduced numbers in the blood during PHIV, DC subsets responded efficiently to stimulation with TLR7/8 agonists by up-regulating maturation markers and producing proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines and by potently stimulating allogeneic T cells to proliferate. Moreover, DC subsets from PHIV subjects exhibited hyperactivation through their expression of elevated levels of maturation markers and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in response to stimulation with TLR7/8 agonists. Although we did not find evidence for infection of circulating blood DCs, we did observe that ex vivo unstimulated DCs had increased surface expression of costimulatory molecules and increased TLR and immune-related gene expression, reflecting either direct or indirect effects of HIV infection.

Our data establish that the reduction in blood DC numbers begins very early in HIV infection at Fiebig stage I-II. We show that DC numbers rebound over time, although they fail to reach the same levels as in uninfected. We observed enhanced TLR-stimulated up-regulation of CCR7 expression by the DCs (data not shown) and a gene expression profile indicative of in vivo activation. Lymph node trafficking has been shown to contribute to blood DC loss in acute simian immunodeficiency virus32 and PHIV,33,34 however, further studies are needed to determine the contribution that other mechanisms of blood DC loss, such as death from direct infection,16 decreased differentiation from DC progenitors, or compromised bone marrow function.

An important finding from this study was that DC numbers were also reduced in ECs. This finding supports the idea that blood DC loss may be related more to the cytokine response to HIV infection than to the extent of viremia. ECs, who maintain undetectable levels of viremia in the absence of ART, do not completely escape HIV pathogenesis. Immune activation and disease progression has been demonstrated with somewhat higher levels of CD38+HLADR+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells than uninfected subjects,35 and some controllers exhibit declining CD4+ T-cell counts over time.36 Therefore, even clinically undetectable viral levels affect host immune responses. The reduction in DC numbers of all patient populations we observed, regardless of innate or ART-induced control of viremia, suggests that even residual levels of virus may be sufficient to directly or indirectly cause tissue homing of peripheral DCs, DC destruction, and/or decreased DC differentiation from progenitors.

Previous studies have reported dysfunction of DC subsets from HIV-infected subjects at various stages of infection.8,22,37 Our evaluation of purified DC subsets in PHIV did not reveal any defects in their response to stimulation with TLR7/8 agonists. As shown previously, mDCs did not mature or produce cytokines in response to AT-2 HIV. Discrepancies between our results and those of others may be based upon differences in TLR agonists used. For instance, Kamga et al used the TLR9 ligand herpes simplex virus to stimulate pDCs from acutely HIV-infected patients and found that they produced less IFNα than pDCs from uninfected controls.8 We also observed reduced IFNα production by pDCs from PHIV subjects at all Fiebig stages in response to herpes simplex virus stimulation (data not shown). It is known that different TLR agonists stimulate pDCs differentially, characterized best by synthetic TLR9 ligands CpGA and CpGB.38 Furthermore, unlike the up-regulated expression of TLR7 observed in PHIV subjects, the expression of TLR9 was not differentially altered (data not shown). Although it is likely that DCs exposed to HIV in vivo may respond less well to other TLR agonists, we show that DC subsets from PHIV subjects do not appear to be grossly dysfunctional in their response to TLR7/8 agonists R848 and HIV.

This study provides important evidence that DCs may contribute to immunopathological immune activation during HIV infection, particularly during PHIV. The excessive immune activation observed in HIV infection is a more important cause of CD4+ T-cell decline and disease progression than viral load, suggesting that the direct cytopathic effects of HIV on target cells are not the sole contributors to AIDS pathogenesis.39,40 We showed that DC subsets from PHIV subjects expressed higher levels of surface markers and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines including IL-6, TNF, MIP1α, MIP1β, and RANTES in response to stimulation with R848 compared with DCs from uninfected subjects. We also observed significant levels of sCD14 providing evidence for the presence of increased circulating lipopolysaccharides (data not shown). Our findings support published reports of increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the peripheral and gut lymphoid tissues during PHIV41 and suggest that sustained triggering of TLR7 on DCs, presumably by HIV, may be involved in inducing immune activation and lymphoid system disruption.42

Although the mechanisms of chronic immune activation are largely unknown, 2 models involving the direct and indirect triggering of innate immune responses by HIV during chronic infection are emerging. Ongoing low-level type I IFN production by chronically HIV-activated pDCs may be a driving force for increased activation, cell turnover, and apoptosis of multiple cell types, including T cells. Bacterial translocation that results from massive CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue by HIV may result in elevated levels of bacterial products containing lipopolysaccharides and CpGs that could activate innate immune cells, including DCs,43 through binding of TLRs to induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines. Consistent with these hypotheses, we (data not shown) and others28,34,44 have observed slightly up-regulated levels of CD40 and/or CD86 on, as well as the spontaneous production of cytokines/chemokines30,45 by circulating DC subsets from HIV-infected subjects. IFNα has been shown to up-regulate the expression of TLRs in macrophages46 ; and PBMCs from chronically HIV-infected subjects have increased expression of TLRs.47,48 Furthermore, we show up-regulation of TLR7 as well as enrichment of interferon-stimulated genes such as STAT1, GBP1, IFIH1, and IFI16 in cells from PHIV subjects compared with uninfected subjects, indicative of in vivo activation and consistent with published reports.49 Although we did not find evidence of direct infection of DCs by either QPCR for the presence of virus and viral outgrowth in DC-T-cell cultures (data not shown), our findings reveal that DCs are dysregulated during PHIV to produce high levels of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines.

Our study supports an important role for DCs in immune activation and raises many new questions regarding the impact of DC hyperresponsiveness in activation during acute HIV infection. DCs are important in stimulating the adaptive immune response, including T cells, B cells, and regulatory T cells, and also in activating other innate immune effectors such as natural killer cells. T-cell and B-cell priming and activation are dependent upon the cytokines produced by DCs and their expression of costimulatory molecules. Additionally, it has been shown that HIV-activated pDCs induce regulatory T-cell formation through an indoleamine 2,3-dioxigenase-dependent mechanism.31 Future studies are needed to understand (1) the effect of DC dysregulation in acute HIV infection on adaptive immune responses, regulatory responses, and natural killer responses and (2) mechanisms by which HIV directly and indirectly stimulates DCs during acute infection to become hyperresponsive.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Olivier Manches and Sonia Barranda-Jimenez for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank JoAnn Kuruc, Alyssa Sugarbaker, Jennifer Scepanski, Dylan Stein, and Robert Haggerty for recruitment of patients for the study.

This work has been supported by grants through: NIAID Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology grant AI067854, NYU CFAR grant P30AI027742, Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Emerald Foundation, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant nos. AI057127, AI044628, and AI061684. P.B. is a Jenner Institute Investigator and received salary support from a Senior Jenner Fellowship.

National Institutes of Health

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: R.L.S. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted and revised the manuscript; M.O. designed and performed selected experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted and revised the manuscript; A. Subedi, E.T., O.D., A. Stacey, M.S., K.S., J.F., and K.V.S. performed selected experiments; L.Q., N.H., A.N., J.F., and K.V.S. performed selected statistical analysis; R.H., D.G., and M. Marmor collected data; M.L. contributed to experimental design; J.L., F.V., F.S., D.M., and M. Markowitz contributed vital reagents; P.B. contributed to experimental design and revised the manuscript; and N.B. designed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no com-peting financial interests.

Correspondence: Nina Bhardwaj, New York University School of Medicine, 522 First Ave SML 1307, New York, NY; e-mail: Nina.bhardwaj@nyumc.org.

), III-IV (N = 2, ■), and V-VI (N = 9,▧). The panels below show the correlation of (C-E) mDC-induced and (D-F) pDC-induced T-cell proliferation to (C-D) CD4 counts and (E-F) plasma viral load in all the HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using a Spearman correlation.

), III-IV (N = 2, ■), and V-VI (N = 9,▧). The panels below show the correlation of (C-E) mDC-induced and (D-F) pDC-induced T-cell proliferation to (C-D) CD4 counts and (E-F) plasma viral load in all the HIV-infected subjects at Fiebig stages I-VI. Statistical analysis was performed using a Spearman correlation.