Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells provide a unique barrier to semiallogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantation. In the setting where the parents donate to the F1 offspring, rejection of parental bone marrow occurs. This “hybrid resistance” is completely NK cell dependent, as T cells in the F1 recipient tolerate parental grafts. Previously, we demonstrated that rejection of BALB/c parental BM by (BALB/c × C57BL/6) F1-recipient NK cells is dependent on the NKG2D-activating receptor, whereas rejection of parental C57BL/6 BM does not require NKG2D. BALB/c and B6 mice possess different NKG2D ligand genes and express these ligands differently on reconstituting BM cells. Herein, we show that the requirement for NKG2D in rejection depends on the major histocompatibility complex haplotype of donor cells and not the differences in the expression of NKG2D ligands. NKG2D stimulation of NK cell–mediated rejection was required to overcome inhibition induced by H-2Dd when it engaged an inhibitory Ly49 receptor, whereas rejection of parental BM expressing the ligand, H-2Kb, did not require NKG2D. Thus, interactions between the inhibitory receptors on F1 NK cells and parental major histocompatibility complex class I ligands determine whether activation via NKG2D is required to achieve the threshold for rejection of parental BM grafts.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells play an important role in immunity to pathogens and tumors.1 NK-cell recognition of infected or transformed cells depends on the expression of stress-induced self-ligands or pathogen-encoded ligands that are detected by activating receptors.2 Similarly, cells that are rapidly proliferating or have experienced DNA damage often express stress-induced ligands that trigger activating receptors on NK cells.3

One shared trait of viruses and tumors is to avoid detection by CD8+ T cells by down-regulating the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I. To counter this situation, NK cells have evolved the ability to kill cells that are “missing self,” (ie, express little to no MHC class I).4 The lack of MHC class I expression, through the deficiency of β2-microglobulin, TAP-1, or MHC heavy chains, evokes NK cell–mediated attack against otherwise healthy cells.5,6 Therefore, NK cells must have stringent safeguards to restrain their effector functions. This control of NK-cell activation is accomplished by inhibitory receptors for polymorphic MHC class I molecules, including Ly49 receptors in rodents and the killer cell immunoglobulin (Ig)–like receptors (KIRs) in humans.1

Many of the same activating receptors that NK cells use to police for pathogens and tumors are involved in the rejection of bone marrow (BM) transplants.7-10 The rejection of BM is also influenced by inhibitory signals received by interactions with donor MHC class I.11,12 In fully allogeneic transplants, the donor BM is not matched with the recipient's MHC; therefore, some NK cells in the recipient will not be inhibited by the allogeneic MHC class I on the donor BM cells and will reject the graft. In the situation in which semiallogeneic parental BM is transplanted into an F1 offspring, the T cells remain tolerant13 ; yet, NK cells in the F1 recipient reject the parental BM graft, a phenomenon known as “hybrid resistance.”14

Hybrid resistance can be partially explained by the expression patterns of inhibitory receptors for MHC class I on NK cells. KIRs and Ly49 are expressed stochastically, resulting in subsets of NK cells defined by their pattern of KIR or Ly49 expression.1 Curiously, a subset of NK cells fails to express inhibitory receptors for self-MHC class I, yet these NK cells are tolerant and do not cause autoimmunity.15,16 Although the activating pathway(s) required for the killing of BM cells by “missing-self” recognition are currently unknown, the concept of “missing-self” provides an explanation for hybrid resistance. In the F1 recipient, a subset of NK cells that expresses an inhibitory receptor for maternal MHC class I, yet does not express an inhibitory receptor for paternal MHC class I haplotype (“missing-self”), is able to reject paternal BM cells and vice versa for maternal BM.

The best-characterized activating receptor important to BM rejection in mice is Ly49D.7-9 Although ligands for Ly49D are not well defined, depletion of NK cells expressing Ly49D in C57BL/6 (B6) or F1 mice abrogates rejection of BALB/c (H-2d) BM in one model of hybrid resistance.7 In addition, B6 mice require Ly49D to reject BM from congenic mice expressing H-2Dd.17 In vitro studies have also shown that Ly49D+ NK cells can kill H-2Dd–expressing targets.8

The activating receptor, NKG2D, expressed on all NK cells, is necessary for the (BALB/c × B6) F1 rejection of BALB/c parental, but not B6 parental, BM.10 The ligands for NKG2D are structurally similar to MHC class I molecules and are polymorphic, but do not associate with β2-microglobulin or present peptides.3 These ligands include the Rae-1 family of glycoproteins, and the related murine UL16-binding protein-like transcript 1 (MULT-1) and H60 glycoproteins. NKG2D ligands are not expressed in high amounts on healthy, resting cells, but are up-regulated in response to inflammation and cellular proliferation.3 In addition, NKG2D ligands are frequently expressed on primary tumors in cancer patients.18 Expression of NKG2D ligands on mouse tumor cell lines renders them susceptible to killing in vivo and in vitro by NK cells.19,20 In this study, we addressed how NKG2D and its ligands influence hybrid resistance.

Methods

Mice and antibodies

BALB/cAnNCr, C57BL/6NCr (B6), and CB6F1/Cr (BALB/cAnNCR × C57BL/6NCr) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. C.B10 (BALB/c mice congenic at H2b from C57BL/10) and B10.D2 (C57BL/10 mice congenic at H2d from DBA/2) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6 and C57BL/10 express the same Raet1 loci.21 C.B10 mice were bred with BALB/c mice to obtain (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 mice. Animal care and procedures were done in accordance with University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. YE1/48 monoclonal antibody (mAb) reacts with Ly49A in BALB/c and B6; 5E6 mAb reacts with Ly49C and Ly49I in B6 and with Ly49C in BALB/c; 4E5 mAb binds to Ly49D in B6; 3D10 mAb reacts with Ly49H in B6; 4D11 mAb binds to Ly49G2 in B6 and BALB/c; 12A8mAb binds to Ly49D and Ly49A in B6 and Ly49A in BALB/c. All experiments with mice were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Transplantation

Recipient F1 mice received 2 doses at 550 rad of 137Cs-irradiation 3 hours apart and then received 4 × 106 BM cells intravenously.10 Recipient mice were given 200 μg of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid sodium salt (poly I:C; Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on day −1 to boost NK-cell function. Five days later, mice were treated with 65 μg of IUdR (5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS intravenously to suppress endogenous thymidine synthesis 1 hour before injection of 3 μCi [125I]-IUdR (Amersham) intravenously. Spleens were harvested the next day, and radioactivity was measured. As indicated, recipients were treated with 200 μg of anti-NKG2D (CX5) and anti-Ly49D+Ly49A (12A8; gift from Dr M. Nakamura, UCSF) on days −2 and +1 relative to transplantation. Statistics were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

NK cells

Splenocytes were incubated at 4 °C for 15 minutes with anti–glycophorin A (Ter119), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD5 (53-7.3), anti-CD8 (YTS 169.4), and anti-CD19 (1D3), washed, and then resuspended with metallic beads coated with goat anti–rat IgG (QIAGEN) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Antibody-labeled cells were removed by magnetic separation.

NK-cell stimulation with mAbs

Ninety-six–well flat-bottom plates were coated with anti-Ly49D (4E5), anti-Ly49H (3D10), anti-NKG2D (CX5; eBioscience), polyclonal goat anti-NKp46 (R&D Systems), anti–DNAM-1 (TX.42-1, gift from Dr A. Shibuya), or control IgG (eBioscience) at 10 μg/mL overnight at 4 °C. Enriched NK cells were plated at 5 × 105 per well for 4 hours at 37 °C in the presence of phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-CD107a (Becton Dickinson).

NK-cell stimulation with lymphoblasts

This assay was performed as previously described.12 Splenocytes (1 × 107/mL) were incubated in 5 μg/mL Concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 hours. Lymphoblasts were enriched over a Lympholyte M gradient (Cedarlane) and used as targets for NK cells prepared from F1 mice that received 200 μg of poly I:C 24 hours prior. Targets and NK cells were incubated at a 1:1 ratio (2-4 × 105 total cells) in 96-well, U-bottom plates at 37°C for 4 hours. NK cells were analyzed on a BD LSRII (Becton Dickinson) using FlowJo software (Version 7.5; TreeStar). Anti–H-2Dd (34-5-8S) and anti–H-2Kb (AF6-88.5) were added at 10 μg/mL (a saturating concentration) to block MHC class I interactions. Specific CD107a staining was calculated as percentage of NK cells spontaneously staining for CD107a minus the percentage of NK cells staining for CD107a in the presence of target cells. Statistics were calculated using the Student t test.

Results

NK cells in CB6F1 mice

NKG2D is required for the rejection of BALB/c, but not C57BL/6, BM by F1 recipients.10 Here, we addressed whether this differential response was due to the presence of different NKG2D ligands or different H-2 ligands in these 2 mouse strains. Therefore, we first characterized the expression of the Ly49 receptors in CB6F1-recipient mice. NK cells in B6 (H-2b) mice express Ly49C and Ly49I, which interact with H-2b, primarily H-2Kb, 22 and Ly49G2 and Ly49A, which do not interact with H-2b. NK cells in BALB/c mice express the inhibitory receptors, Ly49A and Ly49G2, which bind self-MHC class I H-2d, primarily H-2Dd.22 NK cells in B6 mice also express the activating receptors, Ly49D and Ly49H. Ly49H binds to the mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) protein, m157,23 but does not interact with MHC class I. Ly49D weakly interacts with H-2Dd.24 To evaluate the role of these receptors in hybrid resistance, we characterized the NK cells in CB6F1 mice for expression of the Ly49 receptors from both parental strains (Figure 1A). The percentage of NK cells in CB6F1 mice that express the inhibitory receptors, Ly49G2 and Ly49C/I (the mAb used cross-reacts with Ly49C and I), was similar to the percentages of NK cells expressing these receptors in BALB/c mice, but lower than in B6 mice (Table 1). The apparent amount of Ly49G2 and Ly49C/I on NK cells in CB6F1 mice was slightly higher (as determined by mean fluorescent intensity) than in BALB/c mice. In addition, BALB/c do not possess Ly49I; therefore, F1 mice have only the B6 allele of Ly49I. Expression of Ly49D and Ly49H on the NK cells in the F1, compared with B6, revealed that the amount was relatively maintained for Ly49H and slightly lower for Ly49D (Figure 1A). This reduced expression of Ly49D might be due to interactions with H-2Dd in the F1. The percentages of Ly49D+ and Ly49H+ NK cells in the F1 mice were not exactly half of B6, suggesting that these receptors are expressed in a biallelic manner on at least some NK cells in the F1 mice25 (Table 1). In addition, in these F1 mice, a higher percentage of Ly49D+ NK cells coexpressed more Ly49G2 and lower amounts of Ly49C/I than the Ly49D− NK-cell subset (Figure 1B). This was specific to Ly49D, as Ly49H+ NK cells demonstrated no increase in the Ly49C/I+ single-positive subset, compared with the Ly49H− NK-cell subset (Figure 1B). This was similar to the Ly49A+ NK-cell subset in the F1 mice, where two-thirds coexpressed Ly49D+, whereas the Ly49C/I+ NK-cell subset was underrepresented (data not shown). Thus, NK cells in the CB6F1 mice expressing Ly49D preferentially coexpressed inhibitory Ly49 receptors that recognize H-2Dd.

Function of CB6F1 NK cells subsets defined by Ly49. (A) NK cells from peripheral blood of 8-week-old BALB/c, B6, or CB6F1 mice were stained for their Ly49 repertoire. (B) F1 NK cells gated on Ly49A− cells. (C) Enriched splenic NK cells from F1 mice were stimulated with plate-bound antibodies in the presence of anti-CD107a. Bar graph demonstrates mean and SD of triplicate wells. (D) F1 NK cells were incubated with equal numbers of β2−/− lymphoblast blasts in the presence of anti-CD107a. *P < .005 for Ly49A or Ly49G2 versus Ly49C/I subset, no significant difference between Ly49G2 and Ly49A subsets. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Function of CB6F1 NK cells subsets defined by Ly49. (A) NK cells from peripheral blood of 8-week-old BALB/c, B6, or CB6F1 mice were stained for their Ly49 repertoire. (B) F1 NK cells gated on Ly49A− cells. (C) Enriched splenic NK cells from F1 mice were stimulated with plate-bound antibodies in the presence of anti-CD107a. Bar graph demonstrates mean and SD of triplicate wells. (D) F1 NK cells were incubated with equal numbers of β2−/− lymphoblast blasts in the presence of anti-CD107a. *P < .005 for Ly49A or Ly49G2 versus Ly49C/I subset, no significant difference between Ly49G2 and Ly49A subsets. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

One explanation for hybrid resistance is that distinct NK-cell subsets, defined by the lack of inhibitory Ly49 receptors for the parental H-2 haplotype, are responsible for the rejection of parental BM grafts26,27 (Table 2). To compare the response of these NK-cell subsets within a heterogeneous population, we stimulated NK cells from CB6F1 mice with plate-bound antibodies to specific activating receptors and measured their degranulation. All of the NK-cell subsets in the F1 mice, defined by their expression of individual inhibitory or activating Ly49 receptors, responded similarly when stimulated through NKG2D, NKp46, or DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1), which are expressed on the majority of NK cells (Figure 1C). Stimulation through Ly49D also resulted in similar responses within these CB6F1 NK-cell subsets (data not shown). Because Ly49D might interact in cis with H-2Dd and thereby affect NK-cell function, we compared the degranulation of Ly49D+ versus Ly49D− NK cells and found that both groups responded equivalently (Figure 1C), suggesting that chronic interactions between Ly49D and H-2d do not cause hyporesponsiveness of the Ly49D+ NK cells.

The activating NK receptors required to initiate the attack against healthy MHC class I–deficient hematopoietic cells are still unknown. We tested the reactivity of NK-cell subsets in CB6F1 mice against lymphoblasts prepared from Β2m−/− mice. The Ly49C/I+ subset had lower activity, compared with either the Ly49G2+ or the Ly49A+ subsets (Figure 1D). Together, these results suggest that unlike NK cells in B6 mice,15 the Ly49C/I+ NK-cell subset in F1 mice has lower activity in response to MHC class I–deficient lymphoblasts.

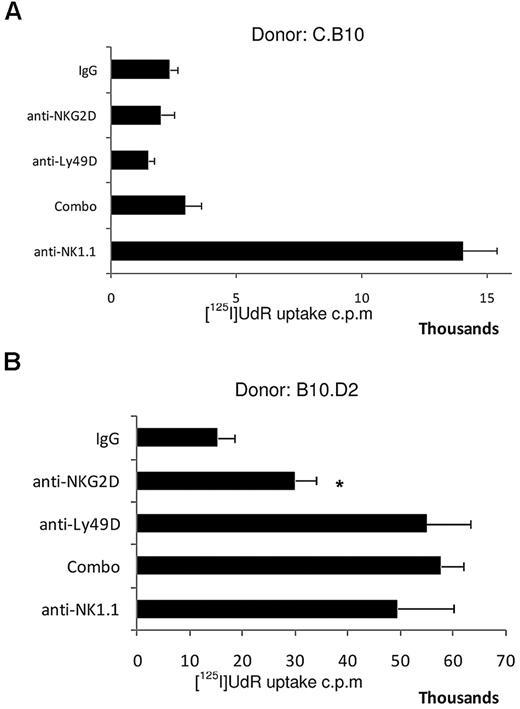

MHC class I–mediated inhibition overcomes NKG2D-dependent BM rejection

We tested the individual and combined contributions of NKG2D and Ly49D to F1 hybrid resistance. NK cells expressing the virus-specific Ly49H receptor become hyporesponsive when chronically exposed to its cognate ligand, the MCMV-encoded m157 glycoprotein.28,29 However, the Ly49D-negative and -postive NK-cell subsets in the F1 mice degranulated equivalently (Figure 1C), despite the fact that Ly49D was putatively being continuously engaged by H-2d. To address the role of Ly49D+ NK cells in vivo, CB6F1 mice were treated with mAb 12A8, which depletes Ly49D+ and Ly49A+ NK cells, thereby eliminating approximately 35% of NK cells in the F1 host (Table 1). Depletion of this subset had no significant impact on the rejection of parental B6 BM, which does not express a MHC class I ligand recognized by Ly49A or Ly49D (Figure 2A). These results indicate that after depletion of the Ly49A- and Ly49D-bearing NK cells, the remaining CB6F1 NK cells are capable of rejecting the B6 parental BM, and this was not blocked by anti-NKG2D (Figure 2A). By contrast, depletion of Ly49D+ NK cells in CB6F1 recipients more significantly impaired the rejection of BALB/c parental BM, and rejection was totally prevented by NKG2D blockade, equivalent to the complete deletion of NK cells (Figure 2B). The influence of depletion of the Ly49D+ NK cell subset in CB6F1 recipients on the rejection of BALB/c parental BM is likely due to the specific elimination of the Ly49D+ NK cells and not just a reduction in the total number of NK cells. Furthermore, the rejection of BALB/c BM in the CB6F1 mice by the Ly49D-positive NK cells was NKG2D dependent, because graft rejection was totally prevented by NKG2D blockade.

NKG2D signaling is insufficient to cause rejection of MHC class I–matched BM. (A) B6 BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. NS indicated no significant difference to IgG control group. (B) BALB/c BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. *P < .008 for anti-Ly49D–treated versus control IgG group and significantly less than other 3 treated groups; P < .008. (C) Transplantation of (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 BM into CB6F1 recipients. Groups consisted of 4-5 mice treated with the reagents noted on the y-axis; “combo” refers to both anti-NKG2D and anti-Ly49D+Ly49A given simultaneously. Error bars represent SEM. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

NKG2D signaling is insufficient to cause rejection of MHC class I–matched BM. (A) B6 BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. NS indicated no significant difference to IgG control group. (B) BALB/c BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. *P < .008 for anti-Ly49D–treated versus control IgG group and significantly less than other 3 treated groups; P < .008. (C) Transplantation of (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 BM into CB6F1 recipients. Groups consisted of 4-5 mice treated with the reagents noted on the y-axis; “combo” refers to both anti-NKG2D and anti-Ly49D+Ly49A given simultaneously. Error bars represent SEM. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Transgenic overexpression of the NKG2D-ligand Rae-1ϵ on B6 BM results in NKG2D-dependent rejection in syngeneic, nontransgenic B6 recipients,10 revealing that expression of NKG2D ligands in high amounts, even in the presence of MHC identity, can promote BM rejection. Therefore, it is possible that CB6F1 recipients reject parental BALB/c BM in an NKG2D-dependent manner, because BALB/c mice express NKG2D-ligands in significantly higher amounts than B6 mice or possess different Raet1 genes than B6 mice.10 To test the role of NKG2D in graft rejection at physiologic levels of NKG2D-ligand expression, we crossed BALB/c mice with C.B10 (BALB/c mice congenic for H-2b), so that the BM in these mice would express NKG2D ligands at levels identical to BALB/c mice because the NKG2D-ligand genes were all from the BALB/c genetic background. CB6F1 recipients did not reject these MHC haploidentical (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 BM grafts (ie, NKG2D-ligandhi/hi, H-2d/b), unlike BALB/c BM (NKG2D-ligandhi/hi, H-2d/d), which was readily rejected in the CB6F1 recipients by an NKG2D-dependent mechanism (Figure 2C). The predominant differences between the (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 and BALB/c BM were the expression of H-2b and half the amount of H-2d on the F1 BM. NK cells expressing Ly49D played only a minor role in rejection and were still dependent on NKG2D (Figure 2B). These results suggest that H-2b on the BM cells is able to completely suppress the NKG2D-mediated rejection of (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 BM grafts, despite the fact that these BM cells are of the same genetic background and express amounts of NKG2D ligands equivalent to BALB/c BM.

Inhibitory signals from H-2Dd reduce NKG2D-mediated NK-cell activity

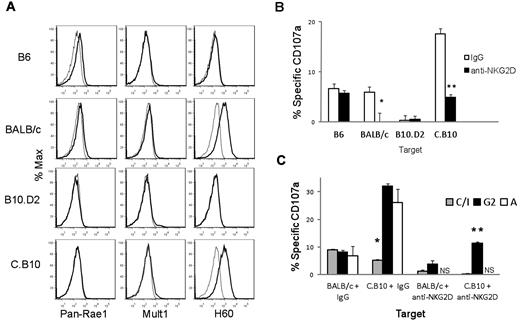

Using lymphoblasts as targets, we explored the relationship between positive signaling from NKG2D and negative signaling from the inhibitory receptors for MHC class I. BALB/c lymphoblasts expressed relatively high levels of H60 (Figure 3A). B6 lymphoblasts, in contrast, expressed only very low, barely detectable, levels of Rae-1 and MULT-1 and lacked H60 (Figure 3A). Similarly, C.B10 lymphoblasts had high levels of H60 (reflecting their BALB/c background), whereas B10.D2 lymphoblasts had low levels of NKG2D ligands (Figure 3A). Therefore, levels of expression of the NKG2D ligands are due to the genetic background. The differential amounts of NKG2D ligand expressed by lymphoblasts from the different genetic backgrounds correlate with their differential expression on BM cells.10

NKG2D-ligand expression levels on ConA-induced lymphoblasts correlates with the magnitude of NKG2D-dependent activation of F1 NK cells. (A) Lymphoblasts from BALB/c and C.B10 were stained for the indicated NKG2D ligands. (B) CB6F1 NK cells incubated with lymphoblasts of the indicated strains with or without a neutralizing anti-NKG2D mAb in the presence of anti-CD107a to detect degranulation. % specific degranulation (CD107a) of the total F1 NK-cell population is shown. *P = .04, **P = .002. (C) Specific degranulation of F1 NK cells within the subsets defined by single expression of Ly49C/I, Ly49A, and Ly49G2 in response to stimulation with the indicated lymphoblasts in the presence of control IgG or a neutralizing anti-NKG2D mAb. *P < .01 Ly49C/I versus either Ly49A or Ly49G2 group; **P < .007 versus Ly49G2 versus Ly49C/I group. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. NS indicates not significant over background.

NKG2D-ligand expression levels on ConA-induced lymphoblasts correlates with the magnitude of NKG2D-dependent activation of F1 NK cells. (A) Lymphoblasts from BALB/c and C.B10 were stained for the indicated NKG2D ligands. (B) CB6F1 NK cells incubated with lymphoblasts of the indicated strains with or without a neutralizing anti-NKG2D mAb in the presence of anti-CD107a to detect degranulation. % specific degranulation (CD107a) of the total F1 NK-cell population is shown. *P = .04, **P = .002. (C) Specific degranulation of F1 NK cells within the subsets defined by single expression of Ly49C/I, Ly49A, and Ly49G2 in response to stimulation with the indicated lymphoblasts in the presence of control IgG or a neutralizing anti-NKG2D mAb. *P < .01 Ly49C/I versus either Ly49A or Ly49G2 group; **P < .007 versus Ly49G2 versus Ly49C/I group. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. NS indicates not significant over background.

Stimulation of CB6F1 NK cells with C.B10 lymphoblasts generated the greatest magnitude of response, as shown by CD107a expression (Figure 3B). Total NK-cell responses to BALB/c and B6 lymphoblasts were similar, while the magnitude of the response was always highest to C.B10 lymphoblasts (Figure 3B). B10.D2 targets were very poor stimulators of NK-cell degranulation. When NKG2D was blocked on CB6F1 NK cells, C.B10 targets induced a response similar to that against B6 targets. Likewise, when NKG2D was blocked, responses to BALB/c targets were more similar to that against B10.D2 targets (Figure 3B). These results suggest that NKG2D augments CB6F1 NK-cell degranulation when stimulated with BALB/c or C.B10 targets, and that the contribution of NKG2D to the response of CB6F1 NK cells against B6 and B10.D2 lymphoblasts is modest. Comparing degranulation induced by targets cells of the same genetic background, that is, B6 (H-2b/b) versus B10.D2 (H-2d/d) and C.B10 (H-2b/b) versus BALB/c (H-2d/d), we consistently observed lower amounts of degranulation in response to targets expressing H-2d than H-2b (Figure 3B). We also analyzed the degranulation of NK-cell subsets defined by the single expression of Ly49C/I, Ly49G2, and Ly49A. The granule release for the Ly49A+ and Ly49G2+ NK-cell subsets followed a predictable pattern; both were inhibited by BALB/c (H-2d/d), but responded robustly to C.B10 (H-2b/b) targets (Figure 3C). Yet, the Ly49C/I subset demonstrated low reactivity to both BALB/c and C.B10 targets, likely because the inhibitory Ly49C and Ly49I receptors react not only with H-2Kb, but also cross-react with H-2d.22 In the presence of anti–NKG2D-blocking antibody, Ly49A+ NK cells showed a dramatic loss in activity, compared with the subsets expressing Ly49G2 or Ly49C/I (Figure 3C). Thus, while all subsets showed some sensitivity to NKG2D blockade, some subsets of NK cells depended more on NKG2D signaling. Together, these results suggest that the cross-reactivity of Ly49C and Ly49I with H-2d and H-2b renders the Ly49C/I+ NK-cell subset a low responder to both parental targets. Comparatively, NKG2D signaling is required to mount a significant NK-cell response against targets bearing H-2Dd.

NKG2D signaling is involved in the rejection of H-2Dd–expressing BM

Our in vitro data suggest that the amounts of NKG2D ligand expressed on targets influence the magnitude of the NK-cell response, and that NKG2D is required to overcome inhibitory signaling induced by H-2Dd. Therefore, we tested the role of NKG2D in the rejection of C.B10 and B10.D2 BM. These experiments addressed whether NKG2D ligands are the primary activating ligands in vivo for cells of the BALB/c-derived background, and if the expression of the inhibitory ligand H-2Dd on BM cells of C57BL/6 background requires NKG2D signaling for rejection. Blocking NKG2D alone did not prevent the rejection of C.B10 (BALB/c background with H-2b) BM by CB6F1 (Figure 4A), and NK cells expressing Ly49D and/or Ly49A were not required. Either blocking NKG2D or depletion of Ly49A- and Ly49D-bearing NK cells augmented acceptance of B10.D2 (C57/BL10 background with H-2d) BM (Figure 4B). In vivo rejection of B10.D2 BM by CB6F1 recipients was weaker than against C.B10 BM, and this stimulatory activity of B10.D2 targets was also evident in the in vitro degranulation assays (Figure 3B). The ability of NKG2D blockade to augment the acceptance of BM derived from the C57BL/10 background indicated that even the low amounts of NKG2D ligands present on BM of this genetic background are functionally relevant. Thus, even low amounts of NKG2D ligand contribute to rejection, and this interaction becomes important in the presence of an inhibitory MHC class I ligand, such as H-2d.

MHC haplotype and amount of NKG2D ligand on BM grafts dictates NKG2D-dependent graft rejection. (A) C.B10 BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. (B) B10.D2 BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P = .032 anti-NKG2D–treated versus control IgG–treated, and anti-NKG2D–treated group is significantly less than anti-Ly49D and Combo groups. Groups consisted of 4-5 mice treated with the reagents noted on the y-axis; “combo” refers to both anti-NKG2D and anti-Ly49D+Ly49A given simultaneously. Error bars represent SEM. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MHC haplotype and amount of NKG2D ligand on BM grafts dictates NKG2D-dependent graft rejection. (A) C.B10 BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. (B) B10.D2 BM was transplanted into F1 recipients. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P = .032 anti-NKG2D–treated versus control IgG–treated, and anti-NKG2D–treated group is significantly less than anti-Ly49D and Combo groups. Groups consisted of 4-5 mice treated with the reagents noted on the y-axis; “combo” refers to both anti-NKG2D and anti-Ly49D+Ly49A given simultaneously. Error bars represent SEM. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

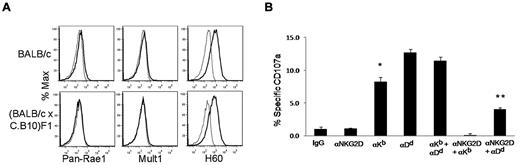

NKG2D is required to overcome H-2Dd, but not H-2Kb, inhibition

Our data suggest that NKG2D is required in the presence of H-2d, likely because most NK cells express inhibitory Ly49 receptors that recognize this MHC haplotype. We tested this possibility by crossing BALB/c with C.B10 mice to obtain (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 mice, which express both H-2Dd and H-2Kb in the presence of high levels of NKG2D ligands due to the BALB/c genetic background (Figure 5A). In this manner, we tested the influence of H-2 on a common genetic background displaying high levels of NKG2D ligand. CB6F1 mice did not reject (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 BM (Figure 2C) and showed no specific degranulation when cocultured in vitro with (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 lymphoblasts (Figure 5B). However, when we blocked the binding of inhibitory receptors to H-2Kb using anti–H-2Kb mAb at saturating concentrations, there was an increase in total NK-cell response. Blocking anti–H-2Dd mAb at saturating concentrations rescued more activity than blocking H-2Kb. Blocking H-2Kb or H-2Dd augmented the degranulation of CB6F1 NK cells against the lymphoblast targets, and the enhanced degranulation was suppressed by anti-NKG2D, indicating that NKG2D is a predominant activating receptor for targets of the BALB/c genetic background. Importantly, a modest amount of NK-cell activity remained even in the presence of anti-NKG2D while blocking H-2Dd, but not H-2Kb. This result correlates with our in vivo findings, showing that rejection of BALB/c, but not C.B10, BM requires NKG2D. These results demonstrate that when physiologic amounts of NKG2D ligands are expressed on target cells, MHC class I effectively dampens NKG2D-dependent NK-cell activation, but in some cases, signaling via NKG2D can overcome this MHC class I–mediated inhibition.

H-2 inhibits NKG2D-dependent NK-cell activation. (A) Expression of NKG2D ligands on lymphoblasts from (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 and BALB/c mice. (B) Enriched NK cells from CB6F1 were cocultured with (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 lymphoblasts in the presence of combinations of blocking antibodies (saturating concentrations) to H-2Kd, H-2Dd, and NKG2D in the presence of anti-CD107a to detect degranulation. *Anti–H-2Kb group is significantly less than either anti–H-2Dd or combo group (P < .002), but there is no significant difference between the anti–H-2Dd versus the combo group. **Anti-NKG2D + anti–H-2Dd group is significantly greater than anti–H-2Kb + anti-NKG2D (P < .0005), but significantly less than MHC class I blocking groups; P = .04 for anti–H-2Kb alone. Bar graphs of results shown are 1 representative experiment of 3 independent experiments performed. Error bars represent SEM.

H-2 inhibits NKG2D-dependent NK-cell activation. (A) Expression of NKG2D ligands on lymphoblasts from (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 and BALB/c mice. (B) Enriched NK cells from CB6F1 were cocultured with (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 lymphoblasts in the presence of combinations of blocking antibodies (saturating concentrations) to H-2Kd, H-2Dd, and NKG2D in the presence of anti-CD107a to detect degranulation. *Anti–H-2Kb group is significantly less than either anti–H-2Dd or combo group (P < .002), but there is no significant difference between the anti–H-2Dd versus the combo group. **Anti-NKG2D + anti–H-2Dd group is significantly greater than anti–H-2Kb + anti-NKG2D (P < .0005), but significantly less than MHC class I blocking groups; P = .04 for anti–H-2Kb alone. Bar graphs of results shown are 1 representative experiment of 3 independent experiments performed. Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that rejection of parental hematopoietic cells by F1 NK cells is regulated by a dynamic balance between positive signals from NKG2D and “missing self” recognition being counteracted by negative signals from inhibitory receptors for MHC class I. Prior studies of hybrid resistance have revealed that this is a remarkably complex process, with the outcome being highly dependent on the genetic background of the donor and recipient strains of mice.14,26 Here, we have used CB6F1 recipients as a model system to explore the relative contribution of NKG2D and MHC class I in this process. The key molecules involved are: (1) the H-2b and H-2d MHC class I, (2) the Ly49 receptors contributed by the BALB/c and B6 NK receptor complexes, and (3) the distinct NKG2D ligands contributed by BALB/c and B6 genetic backgrounds. We demonstrate that, in some cases, NKG2D signaling is required to overcome the inhibitory signals induced by the MHC class I present on the parental BM and allow hybrid resistance.

NKG2D is required to overcome H-2d, but not H-2b, inhibition of BM rejection by CB6F1 recipients. This result could possibly be due to either stronger or broader (ie, engaging a wider array of Ly49 receptors) inhibitory signals provided by H-2d, thereby requiring activation signals provided by NKG2D to initiate NK-cell rejection. The rejection of B6 BM in CB6F1 recipients was not affected by NKG2D blockade; however, rejection of B10.D2 BM was prevented by anti-NKG2D treatment. Of note, rejection of B10.D2 BM was less robust than rejection of B6 BM. Similarly, using in vitro assays CB6F1 NK-cell effectors responded poorly to B10.D2 lymphoblasts. This low response to B10.D2 BM might be due to the combination of low NKG2D-ligand expression and the presence of H-2d on these targets. However, although weaker in magnitude, these results demonstrate that despite the relatively low amount of NKG2D-ligand expressed on cells from the C57/BL6 genetic background, NKG2D ligands have a physiologic impact on F1 hybrid resistance against B10.D2-derived hematopoietic cells. Moreover, these findings imply that NKG2D might be of more consequence in NK-cell responses against targets expressing H-2d, which appears to provide stronger inhibition of NK cell–mediated activation than H-2b. For targets of the BALB/c background, which express NKG2D ligands at higher levels than targets of the C57BL/6 background, again we observed that NKG2D had a more pronounced contribution to responses against targets expressing H-2d than H-2b. The rejection of BALB/c (H-2d) BM was prevented when NKG2D was blocked; however, blocking NKG2D alone did not impair rejection of C.B10 (H-2b) BM. Thus, NKG2D signaling appears to be the dominant signal required to overcome the inhibition conferred by H-2d.

Promiscuity in the H-2 recognition of inhibitory receptors influences the rejection of both allogeneic and semihaploidentical BM. Rejection of BALB/c BM by B6 mice is completely Ly49D dependent.9,12,17 Moreover, in vitro studies demonstrate that reactivity to H-2Dd targets is restricted to the Ly49D+Ly49G2− subset.8 Reactivity to MHC class I–deficient BM in B6 mice is restricted to the Ly49C/I+ subset,15 and indeed, studies show that F1 rejection of BALB/c BM is also dependent upon this subset.7,17 Our results suggest that rejection of BALB/c BM by Ly49D+Ly49C/I+ NK cells in CB6F1 mice occurs because the positive signals induced via Ly49D interacting with H-2d on BALB/C BM cells overcome inhibitory signals transmitted by Ly49C/I interacting with H-2d on these targets. This explanation also applies to in vitro studies evaluating B6 NK-cell lysis of C3H (H-2k) targets7 and why NK cells in B6 mice cannot reject fully allogeneic C3H BM grafts.13 In this situation, B6 NK-cell responses to allogeneic C3H targets are minimal—potentially because Ly49C reacts with H-2k—resulting in inhibition of NK-cell effector functions, and Ly49D does not interact with H-2k to overcome this inhibition.22 The ability of activating signals from Ly49D to overcome H-2–dependent inhibition of BM rejection is supported by studies demonstrating that the Ly49D+Ly49C/I+ NK-cell subset in (B6 × BALB/c.NK1.1) F1 recipients was responsible for the rejection of BALB/c BM.7 In that study, the inhibitory signal received by Ly49G2+ or Ly49A+ NK cells that coexpress Ly49D must be qualitatively different from the inhibitory signals transmitted by Ly49C or Ly49I, because Ly49D+ NK cells expressing Ly49G2 or Ly49A were not required for rejection of the BALB/c BM. The conclusions from these prior studies are consistent with the results presented here. We show that CB6F1 rejection of BALB/c is mostly dependent on NKG2D, with Ly49D playing a minor role; however, (BALB/c × C.B10) F1 BM was not rejected. In this situation, the addition of H-2b to the donor marrow was sufficient to prevent rejection. Together, these results suggest that the Ly49C/I+ subset of NK cells that requires NKG2D to reject BALB/c BM is inhibited by H-2b expressed by the (BALB/c × C.B10) BM graft.

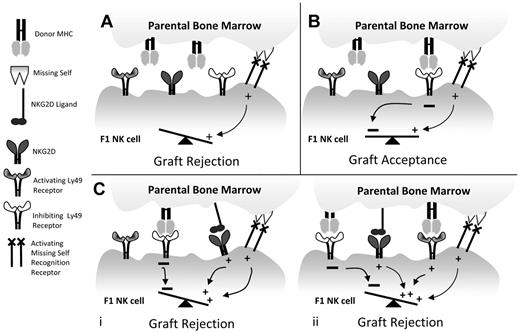

In conclusion, our study explains why hybrid resistance only occurs in some specific instances.14 For in many strain combinations, the BM donors possess MHC haplotypes that react with a majority of inhibitory receptors expressed by NK cells in the F1 recipient and no rejection occurs. Rejection of parental BM only occurs when another activating signal or combination of positive signals is available to overcome this inhibition. In our model system, these addition signals are mediated via either Ly49D or NKG2D. Thus, 3 plausible outcomes of parental BM grafts into F1 recipients exist: (1) the MHC on the donor BM productively engages inhibitory receptors expressed on the majority of NK cells in the F1 recipient preventing parental BM rejection; (2) the MHC on the parental BM does not engage the inhibitory receptors on a sufficient number of NK cells in the F1 host; therefore, the BM is rejected by NK cells expressing the yet unidentified activating receptors mediating missing-self recognition; and (3) an additional signal transmitted by an activating receptor, such as NKG2D, on the recipient NK cells overcomes the inhibition mediated by the inhibitory receptors, allowing graft rejection (Figure 6).

Schematic of hybrid resistance. (A) The classic model for hybrid resistance occurs when a subset of F1 NK cells does not express an inhibitory receptor for parental MHC. Here, missing self-recognition is sufficient to promote BM rejection. (B) Hybrid resistance is prevented when inhibitory receptors on F1 NK cells react with parental MHC and inhibit activation by missing self-recognition. (C) Additional pathways of rejection can occur when NKG2D is engaged on the F1 NK cell, even in the presence of inhibitory signals from binding parental MHC (i). In some subsets of NK cells, 2 additional activating signals (NKG2D and an activating Ly49) are required to overcome the inhibitory receptor signals in F1 NK cells resulting from interactions with parental MHC (ii).

Schematic of hybrid resistance. (A) The classic model for hybrid resistance occurs when a subset of F1 NK cells does not express an inhibitory receptor for parental MHC. Here, missing self-recognition is sufficient to promote BM rejection. (B) Hybrid resistance is prevented when inhibitory receptors on F1 NK cells react with parental MHC and inhibit activation by missing self-recognition. (C) Additional pathways of rejection can occur when NKG2D is engaged on the F1 NK cell, even in the presence of inhibitory signals from binding parental MHC (i). In some subsets of NK cells, 2 additional activating signals (NKG2D and an activating Ly49) are required to overcome the inhibitory receptor signals in F1 NK cells resulting from interactions with parental MHC (ii).

NK-cell alloreactivity, as observed in the hybrid resistance model, is relevant to a number of clinical scenarios. It is proposed to be operative in nonmyeloablative human hematopoietic cell transplantation.30 In addition, a graft-versus-leukemia effect has been observed when recipients with myeloid malignancies receive BM grafts from donors with a donor KIR-recipient MHC class I ligand mismatch.31 Likewise, activated NK cells from haploidentical donors have been infused in patients with refractory malignancies.32,33 Given that human KIR and human leukocyte antigen are very polymorphic34 and human BM cells, like mouse BM cells, express NKG2D ligands,35 NKG2D might well be involved in hybrid resistance in human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, depending on the genetics of the donors and recipients.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Mary Nakamura, Bill Murphy, and Akira Shibuya for generously providing reagents, and Drs Mark Orr, Joseph Sun, and David Hesslein for their helpful comments.

J.N.B. is a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow and was supported by a National Institutes of Health training T32 grant. L.L.L. is an American Cancer Society Professor and was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI066897.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.N.B. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; J.B. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript; and L.L.L. supervised research and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.L.L. and UCSF have licensed intellectual property rights regarding NKG2D for commercial applications. J.N.B. is currently an employee of Novo Nordisk. J.B. declares no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for J.B. is Stanford University, Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, Stanford, CA.

Correspondence: Lewis L. Lanier, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of California San Fransisco, 513 Parnassus Ave, Box 0414, HSE 1001G, San Francisco, CA 94143; e-mail: lewis.lanier@ucsf.edu.