Abstract

Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is detected in approximately 80% of Merkel cell carcinomas (MCC). Yet, clonal integration and truncating mutations of the large T antigen (LTAg) of MCPyV are restricted to MCC. We tested the presence and mutations of MCPyV in highly purified leukemic cells of 70 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. MCPyV was detected in 27.1% (n = 19) of these CLL cases. In contrast, MCPyV was detected only in 13.4% of normal controls (P < .036) in which no LTAg mutations were found. Mutational analyses revealed a novel 246bp LTAg deletion in the helicase gene in 6 of 19 MCPyV-positive CLL cases. 2 CLL cases showed concomitant mutated and wild-type MCPyV. Immunohistochemistry revealed protein expression of the LTAg in MCPyV-positive CLL cases. The detection of MCPyV, including LTAg deletions and LTAg expression in CLL cells argues for a potential role of MCPyV in a significant subset of CLL cases.

Introduction

The Merkel cell polyoma virus (MCPyV) has been reported in approximately 80% of human Merkel cell carcinomas (MCC).1-6 Accumulating evidence of clonal MCPyV integration and truncating large T (LTAg) antigen mutations restricted to MCC strongly support an etiopathogenic role of MCPyV in MCC.1,7 MCC is a rare and aggressive malignant neuroendocrine skin cancer of elderly and immunosuppressed patients.8,9 However, MCC patients are at a 30-fold increased risk to develop chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that as MCC primarily affects elderly patients.10-12

CLL is the most common leukemia in the Western world and is characterized by the accumulation of monoclonal mature B cells aberrantly expressing CD5.13 Recently, a large population based study has shown that CLL patients have a high risk of MCPyV positive MCCs.14 ter Brugge et al have shown that mice expressing the SV40 Tag reveal a normal B cell development but, upon aging, these mice show an accumulation of monoclonal CD5(+) B cells and have a CLL-like phenotype.15 MCPyV is highly related to the lymphotropic polyomavirus (LPV) of African green monkey that is known to infect B lymphocytes.1,16 The presence of MCPyV in peripheral blood at low copy number has been demonstrated recently also suggesting lymphotropism of MCPyV.1,17 A recent study could not find a significant association of CLL with MCPyV.17 Here we report the presence of MCPyV in 19 of 70 highly purified malignant cells of well characterized CLL patients identifying a significant association of MCPyV with CLL particularly underlined by the detection of a novel viral deletion mutant.

Methods

Patients

The study (Cologne Ethics Approval No. 01-163) group included 70 CLL patients of which 47 were male (age range: 27-102 years; mean: 65.1 years) and 23 were female (age range: 45-90 years; mean: 67.2 years). After informed consent, blood was obtained from patients fulfilling diagnostic criteria for CLL. CLL samples were processed immediately after blood withdrawl and processed by applying B-RosetteSep (StemCell Technologies) and Ficoll-Hypaque (Seromed) density gradient resulting in purity of > 98% of CD19+/CD5+ CLL cells as assessed by expression analysis on a FACS Canto flow cytometer (BD PharMingen). CLL cells and patient T-cells were characterized by staining for CD19, CD5, CD3, CD23, FMC7, CD38, ZAP70 and sIgM (BD). DNA of CLL cells was isolated as described before.2

MCPyV detection and mutational analyses by PCR

DNA quality was confirmed by β-globin polymerase chain reaction (PCR).2 MCPyV-PCR using the LT3, M1/M2 and VP1 primer sets was performed as published.1,2 One additional primer set M2mutS (5′-GTTTGAGGCGAGATCTGTTT-3′) and LtmutAS2 (5′-AGCATTTC TGTCCTGGTCAT-3′) encoding T-Ag region (1867-2221) was introduced for mutational analyses. All PCR analyses were carried out at least 3 times independently by N.D.P., A.K., or S.S.

Sequence analyses

PCR products were purified and analyzed by direct sequencing.2 Sequencing results were analyzed and compared with reference sequences of the NCBI Entrez Nucleotide database gb EU375803.1 (MCC350) and gb EU375804.1 (MCC339) using NCBI Blast program. Sequence alignments were performed with BioEdit Version 7.0.9 package.

SYBR green real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed as recently described.18

Immunohistochemistry

MCPyV immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed with the monoclonal antibody CM2B4 (IgG2b isotype) as described recently.19 Minor modifications included pH9.0 and a dilution of 1:1000 (vol/vol). CM2B4 was detected with the DAKO K5005 secondary detection kit (DAKO). Staining was performed using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate and counter-stained with hematoxylin (see Figure 1C).

Prognostic factors

Prognostic factors were assessed as previously published.20 For the determination of the CD38 status a threshold of 7% of positive stained CLL cells was applied for definition of CD38+ patients.

Results and discussion

McPyV detection in CLL and clinico-pathologic correlations

To overcome possible dilution effects due to FFPE tissues or whole blood samples we tested 70 DNA samples derived from highly purified CD5+/CD19+ CLL cells. Of these, 19 (27.1%) were MCPyV-positive. Sixteen (22.8%) were positive by M1/M2 PCR, 1 (1.4%) by LT3 PCR and 2 (2.8%) by VP1 PCR. Sequence analyses of the PCR products revealed only minor nonsynonomous nucleotide changes compared with MCC350.1 Analyzing the viral load on the 19 MCPyV-positive CLL cases revealed 3-4 log lower viral copy numbers compared with MCPyV-positive MCC, which is in line with a previous report of 2 MCPyV-positive CLL cases revealing a 2-4 log lower copy numbers compared with MCPyV-positive MCC.17 No significant correlations with MCPyV and clinico-pathologic parameters, including cytogenetic aberrations by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization, were found. Of the 19 MCPyV-positive CLL cases 16 were male and 3 were female. Taken together we here report a higher detection rate for MCPyV in CLL cases compared with the previous study that is most likely due to the optimal DNA quality derived from the freshly processed and preselected cell material that was used for the current study.

Mutational analysis of the large T gene

We tested the 19 MCPyV-positive CLL cases for previously reported truncating mutations eliminating the helicase domain in the C-terminus of the LTag.7,21 The loss of the helicase activity prevents MCPyV replication and clearly indicates that MCPyV is not a passenger virus in the tumor.17 6 of the 19 MCPyV-positive CLL cases revealed a novel 246 bp deletion within the viral helicase gene (Figure 1A-B). In 2 CLL cases mutated LT was detected concomitant to wild-type MCPyV (Figure 1A). The 246 bp deletion terminates the open reading frame leading to a loss of the helicase domain and thus viral replication deficiency. In 2 of the mutated MCPyV-positive CLL cases formalin fixed and paraffin embedded material of diagnostic bone marrow trephines with nodular CLL infiltrates were available to confirm the presence of MCPyV protein (Figure 1C). The other 13 MCPyV-positive CLL cases revealed minor nucleotide exchanges not disrupting the ORF of LTAg (Figure 1B). Concomitant detection of mutated and wild type MCPyV in CLL DNA might indicate a functional substitution by the MCPyV wild-type helicase. The presence of mutated MCPyV in the 4 other CLL cases indirectly might indicate viral integration in these and might also point to a role of MCPyV in a subset of CLL. We additionally tested 24 MCPyV-positive MCCs of our recent study for this novel 246 bp deletion and detected 1 MCC (4.2%) also carrying the 246 bp deletion without the presence of concomitant MCPyV wild-type. In healthy blood donor derived whole-blood samples we detected significantly less MCPyV-positive cases, that is, 11 of 82 as MCPyV-positive (13.4%; P < .036; χ2 test). It cannot be completely excluded that this significant difference in MCPyV prevalence is partially owed to the fact that the control group is younger. However, none of the healthy donors revealed a truncating deletion within the LTAg.

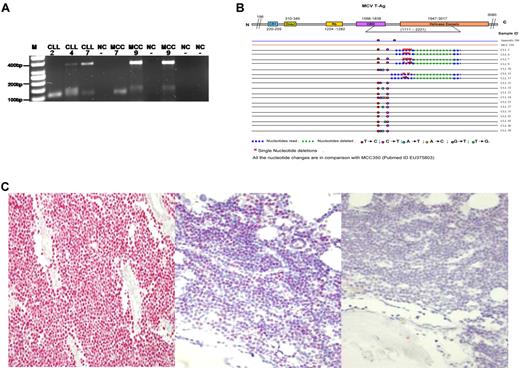

(A) Representative results of the PCR products (355 bp and 120 bp) using DNA of highly purified CD5+/CD19+ CLL tumor cells (2,4,7) and MCC2 (7,9) with LTmutAS2 PCR. The 355 bp bands represent MCPyV wild-type and the 120 bp bands represent mutated MCPyV containing the 246 bp deletion. M, molecular weight marker (50 bp); NC, water control. The numbers indicate the cases as presented in Table 1. Note that the additional 150 bp band in CLL4 and MCC9 has been sequenced and is of nonviral, human genomic origin. (B) Summary of all the sequence data of the LTmutAS2 PCR of 18 MCPyV positive CLL cases according to Shuda et al.7 Although MCPyV positive in the VP1 PCR case number 19 did not show any amplification using the LTmutAS2 PCR and thus is not part of this figure. Single nucleotide mutations are indicated in diverse colors. (C) Left: As positive control a previously MCPyV tested MCC was used revealing specific nuclear staining (red) in the MCC cells.13,14 (Middle) The nodular neoplastic CLL infiltrates within the 2 available corresponding bone marrow trephines revealed specific nuclear expression of the LTAg by IHC (red) whereas nonmalignant hematopoetic cells are MCPyV negative. One of the 2 is cases is shown. (Right) As negative control for MCPyV LTAg IHC the primary antibody (CM2B4) was omitted and no nuclear or cytoplasmic staining was found.

(A) Representative results of the PCR products (355 bp and 120 bp) using DNA of highly purified CD5+/CD19+ CLL tumor cells (2,4,7) and MCC2 (7,9) with LTmutAS2 PCR. The 355 bp bands represent MCPyV wild-type and the 120 bp bands represent mutated MCPyV containing the 246 bp deletion. M, molecular weight marker (50 bp); NC, water control. The numbers indicate the cases as presented in Table 1. Note that the additional 150 bp band in CLL4 and MCC9 has been sequenced and is of nonviral, human genomic origin. (B) Summary of all the sequence data of the LTmutAS2 PCR of 18 MCPyV positive CLL cases according to Shuda et al.7 Although MCPyV positive in the VP1 PCR case number 19 did not show any amplification using the LTmutAS2 PCR and thus is not part of this figure. Single nucleotide mutations are indicated in diverse colors. (C) Left: As positive control a previously MCPyV tested MCC was used revealing specific nuclear staining (red) in the MCC cells.13,14 (Middle) The nodular neoplastic CLL infiltrates within the 2 available corresponding bone marrow trephines revealed specific nuclear expression of the LTAg by IHC (red) whereas nonmalignant hematopoetic cells are MCPyV negative. One of the 2 is cases is shown. (Right) As negative control for MCPyV LTAg IHC the primary antibody (CM2B4) was omitted and no nuclear or cytoplasmic staining was found.

Although the detection of the novel LTAg deletion in MCC (4.2%) and in CLL (8.6%) is relatively rare it might explain the epidemiologic association of MCC and CLL and vice versa.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a relatively high incidence of MCPyV in highly purified CLL cells in 27.1% of patients and the presence of a novel truncating LTAg deletion in 8.6% of CLL and in 4.2% of MCC cases. Our findings indicate MCPyV as an oncogenic virus in B-lymphocytes possibly representing the molecular correlate of the long-term recognized epidemiologic association of CLL and MCC and vice versa. Recent studies revealed sporadic expression of SV40 LTAg in mature B cells as an inducer of a murine CLL-like disease. Future studies will address the transforming properties of the novel 246 bp deletion of MCPyV-LTAg.

Presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO), Mannheim, Germany, October 5, 2009.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of Ann-Kathrin Fritz, Reinhild Brinker, and Julia Claasen. We are thankful for database support by Uta Drebber. We highly appreciate that Patrick Moore and Yuan Chang, University Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, made the LTAg specific antibody (CM2B4) available to us.

C.M.W. was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; Excellence Cluster 229: Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases), German Cancer Aid (Program for the Development of Interdisciplinary Oncology Centers of Excellence in Germany), Bonn, Germany, and the CLL Global Research Foundation, Houston, TX.

Authorship

Contribution: N.D.P. performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, made the figures, and wrote the paper; C.P.P. performed and designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper. A.K.K., A.K., L.F., and S.S. performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; H.M.K. performed research, analyzed data, and edited the paper; C.M.W. was the Principal Investigator at Cologne and designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper; and A.z.H. was the Principal Investigator at Freiburg and designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.z.H. is Department of Pathology, University Hospital Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Correspondence: Axel zur Hausen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology, Maastricht University Medical Center, PO Box 5800, 6202 AZ Maastricht, The Netherlands; e-mail: axel.zurhausen@mumc.nl.

References

Author notes

N.D.P. and C.P.P. contributed equally to this study.