Abstract

Activating mutations in signaling molecules, such as JAK2-V617F, have been associated with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). Mice lacking the inhibitory adaptor protein Lnk display deregulation of thrombopoietin/thrombopoietin receptor signaling pathways and exhibit similar myeloproliferative characteristics to those found in MPN patients, suggesting a role for Lnk in the molecular pathogenesis of these diseases. Here, we showed that LNK levels are up-regulated and correlate with an increase in the JAK2-V617F mutant allele burden in MPN patients. Using megakaryocytic cells, we demonstrated that Lnk expression is regulated by the TPO-signaling pathway, thus indicating an important negative control loop in these cells. Analysis of platelets derived from MPN patients and megakaryocytic cell lines showed that Lnk can interact with JAK2-WT and V617F through its SH2 domain, but also through an unrevealed JAK2-binding site within its N-terminal region. In addition, the presence of the V617F mutation causes a tighter association with Lnk. Finally, we found that the expression level of the Lnk protein can modulate JAK2-V617F–dependent cell proliferation and that its different domains contribute to the inhibition of multilineage and megakaryocytic progenitor cell growth in vitro. Together, our results indicate that changes in Lnk expression and JAK2-V617F–binding regulate JAK2-mediated signals in MPNs.

Introduction

Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are clonal hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) diseases characterized by deregulated proliferation of one or several myeloid lineages. These heterogeneous and phenotypically related disorders include chronic myeloid leukemia, polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF).1 The molecular pathogenesis of MPNs was poorly understood until the identification of the JAK2-V617F mutant allele. This acquired somatic mutation (valine to phenylalanine substitution at position 617, V617F) renders the kinase constitutively active, confers cytokine hypersensitivity, independent growth to hematopoietic cells, and reproduces an MPN phenotype in murine bone marrow transplantation assays.2-6 The JAK2-V617F mutant protein has been identified in approximately 95% of PV, 60% of ET, and 50% of PMF patients.2,7 Recently, gain-of-function point mutations were identified in the cytoplasmic domain of the myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene (MPL), the receptor for thrombopoietin (TPO), in 2% to 5% of ET and PMF patients, respectively. These mutations (MPL-W515L) were shown to induce MPN with marked thrombocytosis in a mouse model.8,9 These findings therefore show that abnormal activation of signaling molecules plays an important role in the pathogenesis of MPNs. However, how defects in these molecules can lead to myeloproliferation in patients remains unknown.

Lnk [also known as Src homology 2 (SH2) B3] is a member of the adaptor protein family composed of SH2-B (SH2B1) and APS (SH2B2). These proteins share common protein-protein interaction domains and motifs: a dimerization domain and proline-rich motifs at the N terminus, a pleckstrin homology (PH) and SH2 domains, and a conserved tyrosine at the C terminus.10 Lnk-deficient mice have demonstrated the importance of this adaptor as a negative regulator of cytokine signaling during hematopoiesis. Analysis of Lnk−/−-derived HSC and myeloid progenitors has shown that Lnk controls TPO-induced self-renewal, quiescence and proliferation of these cells.11-14 Moreover, Lnk−/− animals displayed not only disrupted B lymphopoiesis, but also abnormal megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis, as a result of the absence of negative regulation of TPO and erythropoietin (EPO) signaling pathways, respectively.15-17 Indeed, Lnk, through its SH2 domain, negatively modulates MPL, and EPO receptor (EPOR) signaling by attenuating JAK2 activation. Recently, Lnk was also shown to bind and regulate MPL-W515L and JAK2-V617F forms when expressed in hematopoietic cell lines.11,18,19 These results suggest that these mutant proteins can still undergo Lnk negative regulation.

Of interest is the resemblance between the phenotype displayed by Lnk−/− mice and the biological and clinical characteristics found in MPN patients: hypersensitivity to cytokines, increased number of in vitro multilineage (CFU-GEMM), erythroid (CFU-E), and megakaryocytic (CFU-MK) progenitor colonies, high platelet counts, splenomegaly together with fibrosis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.20,21

In the present study, we aimed to identify molecular defects in Lnk that might explain the myeloproliferative status in MPN patients, notably in those negative for the JAK2-V617F, MPL and Lnk mutations. Expression analysis showed that LNK mRNA was overexpressed in MPN patients and positively correlated with the JAK2-V617F allele burden. Furthermore, our findings demonstrated that Lnk is involved in the regulatory loop TPO, MPL and JAK2 implicated in megakaryopoiesis. Analysis of the Lnk/JAK2 interaction revealed a novel JAK2-binding site within the N-terminal region of Lnk, whose binding was modified by the expression of the JAK2-V617F form. Cell proliferation assays in a JAK2-V617F context showed that the level of expression of Lnk could modulate V617F-dependent cell growth. Together, our results indicate that Lnk can regulate activation of the JAK2-mediated signals associated with MPNs.

Methods

Patient samples and cell purification

MPNs (74; 41 ET, 29 PV, and 4 PMF diagnosed according to World Health Organization criteria), 16 reactive thrombocytosis (RT; secondary to postsurgery inflammatory syndrome) patients, and 21 healthy people were studied, and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. JAK2-V617F mutation detection was performed by single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping assay on purified granulocytes DNA.22 Twenty-seven of 41 ET patients (66%) were found JAK2-WT and MPL-WT by direct sequencing.23 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the PV-Nord group. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Platelets were purified using the platelet-rich plasma (PRP) technique (supplemental data, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and resuspended in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) for subsequent RNA extraction. Bone marrow or peripheral blood CD34+ cells were Ficoll-purified (Amersham Biosciences) followed by magnetic-activated cell sorting selection according to the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec). CD34+ cell purity was verified by flow cytometry (> 95%) and 105 cells were directly resuspended in TRIzol.

Cell cultures and reagents

The human megakaryoblastic UT7/Mpl (clone 5.3, generously provided by D. Duménil, Institut Cochin, Paris, France) and the erythroleukemia HEL cell lines were grown in α-minimum essential medium (MEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics. UT7/Mpl cells were cultivated in the presence of 2 ng/mL of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; PromoCell). COS7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. UT7/Mpl cells were starved in α-MEM plus 0.4% bovine serum albumin and 25 μg/mL transferrin for 12 hours before stimulation with TPO (PromoCell) for the indicated times at 37°C. Cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and immediately resuspended in TRIzol.

RNA preparation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from platelets, CD34+, or UT7/Mpl cells was isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription was performed with 5 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) on all purified RNAs. LNK expression was determined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR; supplemental data). All amplification steps were performed in duplicate.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Purified platelets were TPO-stimulated or not, washed in PBS, and either resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer or lysed for immunoprecipitation. UT7/Mpl cells were starved before stimulation with TPO. HEL cells were washed in PBS before EPO-stimulation. All cells were lysed in ice-cold 1% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer24 for 30 minutes on ice. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 27 000g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and soluble proteins were immunoprecipitated for 2 hours at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were solubilized in SDS sample buffer, analyzed on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis PAGE gels, transferred, and subjected to immunoblotting. Antibody complexes were detected with either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti–mouse or anti–rabbit immunoglobulin (Cell Signaling Technology) and revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; GE Healthcare).

GST pull-down experiments

The N-terminal plus PH domain, SH2 domain, and R364M constructs were previously described.24 The Lnk PH domain (residues 143 to 288) construct was generated by PCR, sequenced, and cloned in pGEX to create an in-frame fusion protein with glutathione s-transferase (GST). The constructs were expressed in BL21 bacteria and purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Amersham). All cell lysates were incubated with 5 μg of GST fusion protein for 2 hours at 4°C. The precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subjected to immunoblotting.

Lin− progenitor cells purification, retroviral transduction, and in vitro colony assays

Lnk point mutations and retroviral supernatant preparation were previously described.24 APS cDNA was subcloned into the MSCV-IRES-GFP (MIG) retroviral vector. Lin− progenitor cells from wild-type (WT), Lnk−/− mice21 or hematopoietic cell lines were retrovirally infected and GFP+ sorted.24 Expression of the transduced genes was verified by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). Triplicate samples of 103 cells (for CFU-GEMM) or 5 × 103 cells (for CFU-Meg) were seeded in methylcellulose media (MethoCult M3434; Stem Cell Technologies) or in collagen-based media (MegaCult-C), respectively, and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. CFU-GEMMs were counted at 8 days after benzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) staining. CFU-Megs were stained for acetylcholinesterase activity (Sigma-Aldrich) and counted after 6 days of incubation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on R package (http://www.R-project.org). Summary statistics were computed, namely percentages for qualitative variables and median with interquartile range for continuous variables. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare distribution function of Lnk according to subsets of patients.

Results

Rare Lnk mutations are associated with MPNs

Activating point mutations in signaling molecules have been associated with MPNs. This has raised the question whether aberrant expression/function of molecules in cytokine receptor signaling can explain MPN clinical phenotypes. Because loss of Lnk in mice results in similar characteristics to those found in MPN patients, we initially searched for mutations in the LNK gene. Recently, 2 different mutations in the PH domain of Lnk were described in 2 of 33 (6%) ET and PMF patients studied.25 We have found one mutation (not reported in public single-nucleotide polymorphism databases) in the N-terminal region of Lnk (G152R) in 1 of 73 (1.4%) ET (JAK2-WT and MPL-WT) patients by granulocyte DNA analysis. Our result combined with those previously published, confirm that Lnk mutations are very rare events, probably less than 5%, and therefore, their role in the pathogenesis of MPNs has to be confirmed by functional assays. Consequently, we aimed in this study to search for molecular defects, other than mutations, that could play a role in the pathogenesis of MPNs.

Lnk expression is up-regulated in MPN patients

We first examined the expression level of LNK in MPNs and whether this could correlate with the percentage of JAK2-V617F mutant allele. LNK mRNA expression was measured by real-time qPCR analysis in platelets from 74 MPNs, 16 RT patients, and 21 healthy people. MPN patients (JAK2-WT and V617F) showed significantly higher expression of LNK transcripts than healthy controls (Figure 1A). Among these patients, no difference in LNK expression was observed between ET and PV samples (P = .74). However, LNK expression was significantly higher in JAK2-V617F-positive patients compared with controls (median [Q1-Q3]: 69 [27-135] vs. 15 [10-38]). Moreover, a positive correlation between the percentage of JAK2-V617F mutant allele and LNK mRNA expression was observed in MPN platelets (supplemental Figure 1). Furthermore, LNK mRNA expression in platelets derived from RT patients was also significantly higher (82 [43-112]) than healthy controls, but relatively similar to JAK2-V617F MPN patients (P = .09). Because RT patients often exhibit elevated serum TPO levels, our findings suggest that LNK overexpression in these patients is caused by an activation of the TPO signaling pathway.26

Lnk is overexpressed in MPNs. (A-B) Relative expression of total LNK mRNA was determined by real-time PCR using either the TaqMan method on purified platelets (A) or the SYB Green method on sorted CD34+ cells (B). Relative LNK mRNA levels are expressed in arbitrary units (A) or log2 (B) of ratios obtained using housekeeping genes for normalization. The horizontal line in the box marks the median and bars indicate the range of values. All P values were 2-sided with P ≤ .05 denoting statistical significance: *P = .0076; **P < .0001; ***P = .004. All patients were studied in duplicate. RT, reactive thrombocytosis; PV, polycythemia vera; PMF, primary myelofibrosis.

Lnk is overexpressed in MPNs. (A-B) Relative expression of total LNK mRNA was determined by real-time PCR using either the TaqMan method on purified platelets (A) or the SYB Green method on sorted CD34+ cells (B). Relative LNK mRNA levels are expressed in arbitrary units (A) or log2 (B) of ratios obtained using housekeeping genes for normalization. The horizontal line in the box marks the median and bars indicate the range of values. All P values were 2-sided with P ≤ .05 denoting statistical significance: *P = .0076; **P < .0001; ***P = .004. All patients were studied in duplicate. RT, reactive thrombocytosis; PV, polycythemia vera; PMF, primary myelofibrosis.

We next examined the expression of LNK mRNA in CD34+ cells isolated from peripheral blood of PMF patients (JAK2-V617F, n = 26 and JAK2-WT, n = 17) by real-time qPCR. Figure 1B showed that LNK expression was significantly increased in CD34+ cells from JAK2-V617F PMF patients (1.56 ± 1.19) compared with cells from healthy donors (bone marrow and peripheral blood controls: 1.03 ± 0.29; n = 16). In contrast, there was no significant difference between JAK2-WT PMF and healthy controls. Markedly increased expression of LNK was also found in 2 of 5 CD34+ cells derived from JAK2-V617F PV bone marrow (Figure 1B), suggesting that LNK overexpression can be found in a proportion of MPN immature progenitors.

No correlation was found between LNK mRNA levels and most of the clinical and biological parameters examined, including history of thrombosis, splenomegaly, WBC, ANC, hemoglobin, platelet counts, and EPO level (Table 1). However, cytoreductive treatment seemed to affect LNK mRNA levels; MPN patients treated with interferon-α (IFN-α) displayed significantly lower levels of LNK mRNA (39 ± 36; n = 18) than those treated with hydroxyurea (145 ± 235; n = 34; P = .04), suggesting that IFN-α can modulate LNK expression. Together, these results show that Lnk is up-regulated in MPNs, notably in those bearing the JAK2-V617F mutation, at the mature cell level, as well as in CD34+ progenitors.

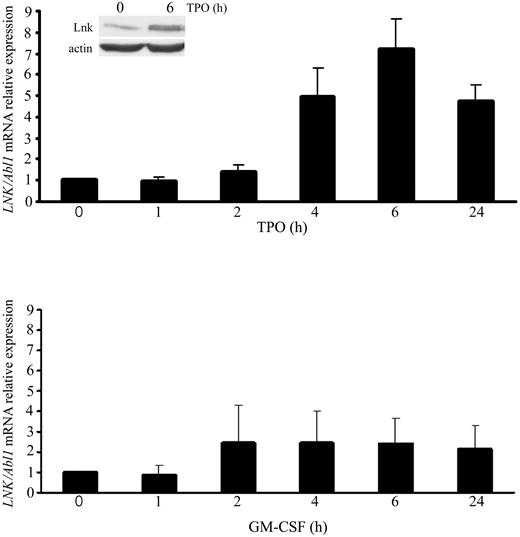

Lnk is regulated by TPO-mediated signaling pathways in megakaryocytes

The elevated LNK expression in RT and JAK2-V617F MPN patients suggested that JAK2 was involved in the induction of LNK mRNA via constitutive activation of TPO signaling. Because proliferation and differentiation of megakaryocytes are mainly controlled by TPO,27 we investigated whether this cytokine could regulate LNK expression in megakaryocytes. Consequently, we quantified the expression of LNK mRNA in UT7/Mpl cells at different time points after TPO stimulation. Real-time qPCR showed that maximal LNK expression is induced after 6 hours of TPO stimulation (Figure 2 top graph). Moreover, concomitant with the increase in mRNA, a 2-fold increase in Lnk protein was also observed after 6 hours of TPO treatment (Figure 2 inset top graph). In contrast, incubation of UT7/Mpl cells with GM-CSF for different times had no effect on the expression level of LNK transcripts, despite expression of the GM-CSF receptor (Figure 2 bottom graph). These results indicate that TPO-mediated signaling specifically regulates Lnk expression at both mRNA and protein levels in human megakaryocytic cells.

Lnk expression is regulated by TPO-mediated signaling in megakaryocytic cells. Relative expression of total LNK mRNA was determined as Figure 1A in UT7/Mpl cells starved for 12 hours and stimulated for the indicated times with TPO (50 ng/mL, top graph) or GM-CSF (2.5 ng/mL, bottom graph). Data represent the mean ± SD (error bars) of LNK/Abl1 mRNA relative expression from 3 independent assays. Western blot analysis of Lnk expression in UT7/Mpl cells was performed with anti-Lnk antibodies and anti-actin as loading control.

Lnk expression is regulated by TPO-mediated signaling in megakaryocytic cells. Relative expression of total LNK mRNA was determined as Figure 1A in UT7/Mpl cells starved for 12 hours and stimulated for the indicated times with TPO (50 ng/mL, top graph) or GM-CSF (2.5 ng/mL, bottom graph). Data represent the mean ± SD (error bars) of LNK/Abl1 mRNA relative expression from 3 independent assays. Western blot analysis of Lnk expression in UT7/Mpl cells was performed with anti-Lnk antibodies and anti-actin as loading control.

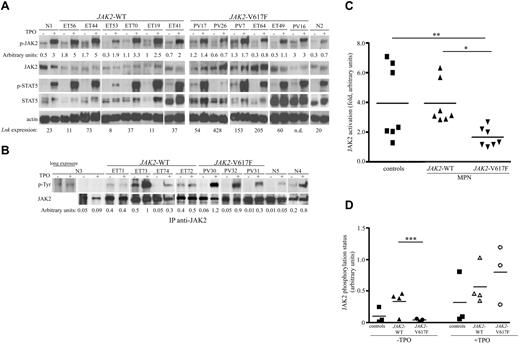

Constitutive JAK/STAT signaling has been associated to JAK2-V617F-positive MPNs, as shown in hematopoietic cell lines or animal models. Because LNK expression was clearly increased in these patients, we examined whether Lnk could affect JAK2 and STAT5 activation in V617F-positive and negative MPNs. Purified platelets were TPO-stimulated or not, and total cell lysates were analyzed with anti-phospho-JAK2– and anti-phospho-STAT5–specific antibodies. JAK2/STAT5 activation was detected in all samples analyzed (Figure 3A and supplemental Figure 2). However, JAK2-V617F-fold activation was significantly lower compared with JAK2-WT samples and controls (Figure 3C). Conversely, the LNK expression level in JAK2-V617F samples was elevated (Figure 3A), suggesting an inhibitory role of Lnk on JAK2 activation. Furthermore, JAK2 immunoprecipitations followed by anti-phosphotyrosine–specific antibodies analysis showed a significant difference in JAK2 basal phosphorylation in JAK2-V617F compared with JAK2-WT samples (Figure 3B-D). However, both JAK2 forms displayed high TPO-induced phosphorylation. Altogether, these results suggest that the activation/phosphorylation of JAK2-WT and V617F forms is regulated differently by Lnk in MPN patients.

Activation of JAK/STAT signaling pathways in MPN platelets. (A) Total platelet lysates from MPN patients (JAK2-WT and V617F) and healthy donors (N) were stimulated (+) or not (−) for 10 minutes with TPO (100 ng/mL) and then subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-phospho-JAK2 (p-JAK2) and anti-phospho-STAT5 (p-STAT5) antibodies. Total JAK2 and STAT5 levels were analyzed with anti-JAK2 and anti-STAT5 antibodies. Blot quantification was performed with multi Gauge software (Fujifilm). Numbers under the phospho-JAK2 blots show the ratios (arbitrary units) of phospho-JAK2/total JAK2. Actin blot is shown as loading control; numbers under this blot denote the mRNA expression level of LNK for each patient. (B) Platelet lysates from healthy donors (N), JAK2-WT and V617F MPN patients were stimulated with or without TPO for 10 minutes and immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK2 antibodies. Western blot analysis with anti-phosphotyrosine (anti-p-Tyr) antibodies allowed identification of phosphorylated JAK2 protein (top panel). Total JAK2 protein expression is shown (bottom panel). Numbers under the p-Tyr blots show the ratios (arbitrary units) of phospho-JAK2/total JAK2. ET, essential thrombocythemia; PV, polycythemia vera; n.d., not done. (C) Graphic representation of JAK2-fold activation. Data represent the normalized ratios of TPO-induced phospho-JAK2/nonstimulated phospho-JAK2 from (A). Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test: *P = .0025; **P = .0386. (D) Graphic representation of JAK2 phosphorylation status, data represent the normalized ratios of p-TyrJAK2/total JAK2 (arbitrary units) from panel B, ***P = .047.

Activation of JAK/STAT signaling pathways in MPN platelets. (A) Total platelet lysates from MPN patients (JAK2-WT and V617F) and healthy donors (N) were stimulated (+) or not (−) for 10 minutes with TPO (100 ng/mL) and then subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-phospho-JAK2 (p-JAK2) and anti-phospho-STAT5 (p-STAT5) antibodies. Total JAK2 and STAT5 levels were analyzed with anti-JAK2 and anti-STAT5 antibodies. Blot quantification was performed with multi Gauge software (Fujifilm). Numbers under the phospho-JAK2 blots show the ratios (arbitrary units) of phospho-JAK2/total JAK2. Actin blot is shown as loading control; numbers under this blot denote the mRNA expression level of LNK for each patient. (B) Platelet lysates from healthy donors (N), JAK2-WT and V617F MPN patients were stimulated with or without TPO for 10 minutes and immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK2 antibodies. Western blot analysis with anti-phosphotyrosine (anti-p-Tyr) antibodies allowed identification of phosphorylated JAK2 protein (top panel). Total JAK2 protein expression is shown (bottom panel). Numbers under the p-Tyr blots show the ratios (arbitrary units) of phospho-JAK2/total JAK2. ET, essential thrombocythemia; PV, polycythemia vera; n.d., not done. (C) Graphic representation of JAK2-fold activation. Data represent the normalized ratios of TPO-induced phospho-JAK2/nonstimulated phospho-JAK2 from (A). Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test: *P = .0025; **P = .0386. (D) Graphic representation of JAK2 phosphorylation status, data represent the normalized ratios of p-TyrJAK2/total JAK2 (arbitrary units) from panel B, ***P = .047.

Lnk associates with active JAK2-WT and V617F via its SH2 domain

Members of the SH2B family have been shown to directly associate with JAK2 via their SH2 domain and the phosphorylated tyrosine residue 813 (pY813) in JAK2. This association is required for the regulation of JAK2 activity and phosphorylation of the adaptors by the kinase.28,29

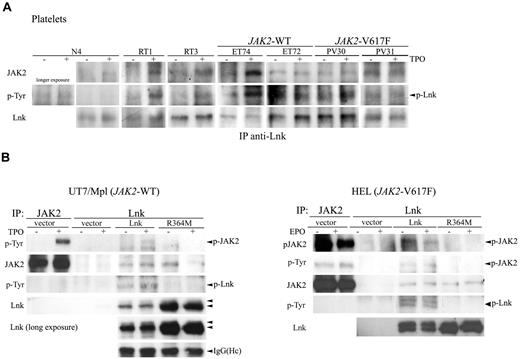

To determine whether the Lnk/JAK2 interaction has a pathophysiological significance in MPNs, we examined their association in platelets derived from healthy donors, RT, and MPN (JAK2-WT and V617F) patients. Platelets lysates previously TPO-stimulated or not were immunoprecipitated with anti-Lnk antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-JAK2 and anti-Lnk antibodies. Lnk coimmunoprecipitated with JAK2 in control samples (healthy donors and RT) after TPO-stimulation, which resulted in Lnk phosphorylation (Figure 4A). However, a weak Lnk/JAK2 interaction was sometimes detected in nonstimulated cells. In contrast, Lnk was constitutively associated with JAK2 and phosphorylated in WT and V617F MPNs cells. These data show for the first time in the context of RT and MPN platelets that Lnk binds to activated JAK2 and subsequently becomes a substrate of the kinase. This interaction was also detected with the JAK2-V617F mutant form demonstrating that this mutation does not affect the Lnk/JAK2 association.

Lnk interacts with JAK2-WT and V617F via its SH2 domain. (A) Platelets from healthy donor, RT and MPN patients were stimulated as in Figure 3 and immunoprecipitated with anti-Lnk antibodies. Western blot analysis with anti-JAK2 antibodies revealed associated JAK2 (top panel). Phosphorylated Lnk was detected with anti-p-Tyr antibodies (middle panel) and Lnk protein expression is shown with anti-Lnk antibodies (bottom panel). (B) Total lysates from UT7/Mpl (left panel) or HEL (right panel) cells expressing control vector or Lnk forms were stimulated with TPO (100 ng/mL) or EPO (50 U/mL), respectively, for 10 minutes and then immunoprecipitated with anti-Lnk antibodies. Western blot analysis was performed with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-phospho-JAK2 antibodies (top right panel). Anti-JAK2 immunoprecipitations are shown as control for JAK2 size. JAK2 and Lnk protein expression were detected with anti-JAK2 and anti-Lnk, respectively. A longer exposure of the Lnk blot (left panels) shows Lnk as a doublet (arrows). IgG (Heavy chain, Hc) blot is shown as immunoprecipitation control in left panel. All shown experiments have been repeated at least 3 independent times.

Lnk interacts with JAK2-WT and V617F via its SH2 domain. (A) Platelets from healthy donor, RT and MPN patients were stimulated as in Figure 3 and immunoprecipitated with anti-Lnk antibodies. Western blot analysis with anti-JAK2 antibodies revealed associated JAK2 (top panel). Phosphorylated Lnk was detected with anti-p-Tyr antibodies (middle panel) and Lnk protein expression is shown with anti-Lnk antibodies (bottom panel). (B) Total lysates from UT7/Mpl (left panel) or HEL (right panel) cells expressing control vector or Lnk forms were stimulated with TPO (100 ng/mL) or EPO (50 U/mL), respectively, for 10 minutes and then immunoprecipitated with anti-Lnk antibodies. Western blot analysis was performed with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-phospho-JAK2 antibodies (top right panel). Anti-JAK2 immunoprecipitations are shown as control for JAK2 size. JAK2 and Lnk protein expression were detected with anti-JAK2 and anti-Lnk, respectively. A longer exposure of the Lnk blot (left panels) shows Lnk as a doublet (arrows). IgG (Heavy chain, Hc) blot is shown as immunoprecipitation control in left panel. All shown experiments have been repeated at least 3 independent times.

Lnk was recently reported to interact with JAK2 through its SH2 domain in response to TPO stimulation. We examined whether this domain was necessary for Lnk/JAK2 association in a JAK2-WT and V617F context. First, we infected UT7/Mpl (JAK2-WT) cells with retroviral supernatants expressing control vector, WT, or SH2-inactive Lnk mutant (R364M) form. Lnk immunoprecipitation analysis on UT7/Mpl infected cells showed that only WT Lnk associated with activated JAK2-WT, this interaction resulting in Lnk phosphorylation (Figure 4B first and third left panels). In contrast, the R364M mutation highly diminished Lnk association with activated JAK2-WT and abolished Lnk phosphorylation. Interestingly, we could detect an interaction between WT or R364M Lnk and nonphosphorylated JAK2 (Figure 4B second left panel), which suggests that Lnk can bind to inactive JAK2 through another domain.

We next analyzed Lnk/JAK2 interaction in a V617F context. HEL (JAK2-V617F) cells infected with the different Lnk forms, as described above, were stimulated with EPO and immunoprecipitated with anti-Lnk antibodies. Our data confirmed that Lnk also binds JAK2-V617F form via its SH2 domain, resulting in constitutive Lnk phosphorylation (Figure 4B right panels). Moreover, an interaction with R364M Lnk could now be observed with this JAK2 active form, suggesting a change in the Lnk/JAK2 interaction in the presence of the V617F mutation (Figure 4B third right panel). This result also supports the implication of a second Lnk domain in its association with JAK2.

A second JAK2-binding site within Lnk N-terminal region

To identify other domains of Lnk involved in its interaction with JAK2, we performed GST pull-down experiments using GST fusion proteins expressing either the Lnk SH2 domain (SH2), the SH2 inactive form (R364M), the PH domain alone (PH) or together with the N-terminal region (NPH; Figure 5A). UT7/Mpl cells treated with or without TPO were incubated with equal amounts of the different Lnk GST fusion proteins (Figure 5B, bottom panel), and bound proteins were analyzed with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-JAK2 specific antibodies. Only WT Lnk SH2 domain was able to bind to phosphorylated JAK2 (Figure 5B). Neither the R364M, nor the NPH protein could associate with the activated kinase. However, weak binding between the NPH fusion protein and JAK2 was observed in untreated cells when probed with anti-JAK2 antibodies, suggesting an interaction between these domains of Lnk and nonphosphorylated JAK2 (Figure 5B, top panels). A similar result was obtained in COS7 cells transiently expressing JAK2-WT (Figure 5C, left panels). The Lnk SH2 domain was able to pull-down activated JAK2 as revealed by anti–phospho-specific JAK2 and anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies, whereas the NPH protein weakly precipitated probably with nonphosphorylated JAK2 as shown by anti-JAK2 immunoblotting. No JAK2 binding was detected with the GST fusion protein alone or expressing the PH domain. These results suggest that a second Lnk binding site for JAK2 lies within the N-terminal region of the adaptor.

Lnk interacts differently with JAK2-WT and V617F. (A) Schematic representation of GST-Lnk fusion proteins used; R364M mutation is indicated with an asterisk (*). (B) UT7/Mpl stimulated as previously indicated were incubated with GST alone or different GST-fused Lnk domains. (C) COS7 cells transiently transfected with either WT (left panel) or JAK2-V617F (right panel) forms by the polyethyleneimine (PEI; Sigma-Aldrich) method were harvested 48 hours after transfection and lysed as described in methods section. Anti-JAK2 Western blot confirms similar expression of both JAK2 forms. Cell lysates were incubated with GST alone or different GST-fused Lnk domains. Immunoblotting with anti-p-Tyr, anti-phospho-JAK2 and anti-JAK2 antibodies allowed detection of bound activated JAK2 protein. Anti-JAK2 immunoprecipitation and total cell lysate (TCL) are shown as control for JAK2 size. Anti-GST blots are shown as control of equal GST proteins used in the assay, asterisk (*) in panels B-C marks NPH GST protein. All experiments have been performed at least 3 independent times. White space gaps in panels B and C indicate repositioned gel lanes.

Lnk interacts differently with JAK2-WT and V617F. (A) Schematic representation of GST-Lnk fusion proteins used; R364M mutation is indicated with an asterisk (*). (B) UT7/Mpl stimulated as previously indicated were incubated with GST alone or different GST-fused Lnk domains. (C) COS7 cells transiently transfected with either WT (left panel) or JAK2-V617F (right panel) forms by the polyethyleneimine (PEI; Sigma-Aldrich) method were harvested 48 hours after transfection and lysed as described in methods section. Anti-JAK2 Western blot confirms similar expression of both JAK2 forms. Cell lysates were incubated with GST alone or different GST-fused Lnk domains. Immunoblotting with anti-p-Tyr, anti-phospho-JAK2 and anti-JAK2 antibodies allowed detection of bound activated JAK2 protein. Anti-JAK2 immunoprecipitation and total cell lysate (TCL) are shown as control for JAK2 size. Anti-GST blots are shown as control of equal GST proteins used in the assay, asterisk (*) in panels B-C marks NPH GST protein. All experiments have been performed at least 3 independent times. White space gaps in panels B and C indicate repositioned gel lanes.

We next examined the impact of the V617F mutation on JAK2 binding to the different domains of Lnk. After transfection of COS7 cells with JAK2-V617F form (Figure 5C, bottom panel), cell lysates were incubated with equal amounts of the different GST fusion proteins (Figure 5C, GST blot) and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-specific JAK2, anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-JAK2 antibodies. A stronger interaction between Lnk SH2 domain and JAK2-V617F was detected compared with JAK2-WT (Figure 5C, right panels). However, binding was now observed with the NPH and R364M proteins. These results indicate that the expression of the V617F mutation modifies the binding affinity between JAK2 and the adaptor, but not its specificity for Lnk N-terminal region, as shown by the lack of association with the PH domain alone (Figure 5C).

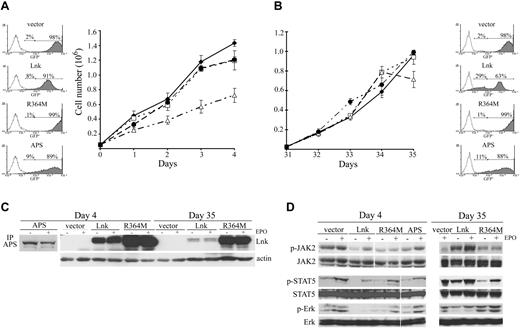

Lnk SH2 domain is necessary for inhibiting JAK2-V617F–mediated proliferation

Lnk is a potent inhibitor of cytokine-dependent cell growth in normal hematopoietic cells.11,16,17,21,24 Therefore, we analyzed the effect of Lnk on cell proliferation in a JAK2-V617F context. Expression of WT Lnk in HEL cells led to significant growth inhibition compared with cells expressing control vector. However, the R364M Lnk mutant form completely abolished this inhibitory function (Figure 6A). Similar results were obtained in the presence of EPO (data not shown). To further emphasize the specific role of Lnk in cell proliferation, cells were infected with APS, a member of the Lnk family. No cell growth inhibition was observed in these cells, demonstrating that this inhibitory function is specific to Lnk. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (GFP-expressing cells) and Western blot analysis further confirmed the level of Lnk, R364M, and APS expression in the culture (Figure 6A-C). We also measured cell proliferation on the same clones 4 weeks later. Cells expressing Lnk seemed no longer able to inhibit cell growth, similarly to vector, R364M, and APS-expressing cells (Figure 6B). Although the same percentage of cells expressed Lnk at day 35 than at day 0 (assessed by the percentage of GFP+ cells), one-third of these cells now expressed lower levels of Lnk. This reduction in expression was shown by the appearance of a second population that results in a lower mean fluorescence intensity of the overall GFP+ cells (205 mean fluorescence intensity at day 35 vs 609 at day 0) and by Western blot analysis (Figure 6A-C).

Lnk inhibits cell growth and signaling in HEL cells. (A-B) HEL cells (5 × 105) expressing different Lnk forms or WT APS were cultured in complete media, and viable cell numbers were determined by trypan blue exclusion at the indicated times with 4 weeks interval (B). Data represent the mean counts ± SD (error bars) of viable cells from triplicate determinations and are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. GFP expression level in all clones was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting; (C) WT and R364M Lnk forms and APS protein expression was assessed with anti-Lnk and anti-APS antibodies, respectively. Actin blot is shown as equal loading control. Vector, ♦; R364M, □; APS, ●; Lnk, Δ. (D) Total lysates from HEL cells expressing different Lnk forms or WT APS were prepared as in Figure 4B at day 4 (left panels) and day 35 (right panels) of culture. JAK2, STAT5, and MAPK activation was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-JAK2 (p-JAK2), anti-phospho-STAT5 (p-STAT5) or anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (p-Erk) antibodies, respectively. Total JAK2, STAT5, and Erk levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. White space gaps indicate repositioned gel lanes.

Lnk inhibits cell growth and signaling in HEL cells. (A-B) HEL cells (5 × 105) expressing different Lnk forms or WT APS were cultured in complete media, and viable cell numbers were determined by trypan blue exclusion at the indicated times with 4 weeks interval (B). Data represent the mean counts ± SD (error bars) of viable cells from triplicate determinations and are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. GFP expression level in all clones was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting; (C) WT and R364M Lnk forms and APS protein expression was assessed with anti-Lnk and anti-APS antibodies, respectively. Actin blot is shown as equal loading control. Vector, ♦; R364M, □; APS, ●; Lnk, Δ. (D) Total lysates from HEL cells expressing different Lnk forms or WT APS were prepared as in Figure 4B at day 4 (left panels) and day 35 (right panels) of culture. JAK2, STAT5, and MAPK activation was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-JAK2 (p-JAK2), anti-phospho-STAT5 (p-STAT5) or anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (p-Erk) antibodies, respectively. Total JAK2, STAT5, and Erk levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. White space gaps indicate repositioned gel lanes.

We further studied the impact of Lnk expression level on the activation of the JAK/STAT and MAPK pathways. High level of WT Lnk correlated with down-regulation of JAK2, STAT5, and MAPK activation, whereas vector, R364M and APS-expressing cells had no effect on these signaling pathways (Figure 6D left panels). In contrast, activation of JAK/STAT and MAPK pathways was no longer inhibited in cells expressing lower WT Lnk level (Figure 6D right panels). These results indicate that the level of Lnk expression is important for modulating JAK2-V617F–mediated responses.

Lnk domains contribute differently to the proliferation of multilineage and megakaryocytic progenitors

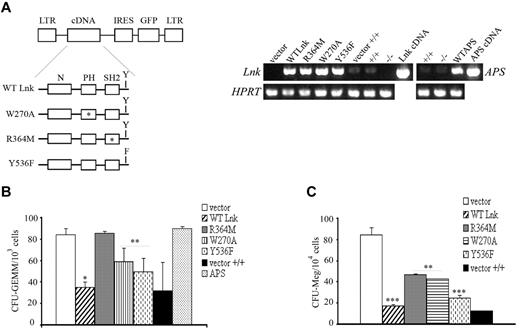

A common characteristic of ET, PMF, and Lnk−/− multilineage and megakaryocytic progenitors is a hypersensitivity to growth factors that confers them proliferative advantage over normal cells. To determine which domain(s) of Lnk is able to control proliferation of multilineage (CFU-GEMM) and megakaryocytic (CFU-Meg) progenitor cells, we retrovirally expressed WT Lnk or mutated forms at its individual domains in Lin− progenitor cells derived from Lnk-deficient animals (Figure 7A left panel). To confirm Lnk specificity, Lnk−/−Lin− cells were also infected with WT APS. Lin−-transduced cells were then sorted based on GFP expression and grown in vitro in methylcellulose media supplemented with different combination of cytokines to assess their clonogenic potential. The expression of the different Lnk forms and APS in Lin− cells was confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 7A right panel).

Lnk domains and Y537 contribute differently to the expansion of myeloid and megakaryocytic progenitors. (A) Schematic representation of WT and Lnk mutant forms cloned into the MIG retroviral vector. Point mutations in the PH domain (W270A), SH2 domain (R364M), and in the C-terminal tyrosine (Y536F) are indicated with an asterisk (*) or F. Total RNA was extracted from WT (+/+) or Lnk−/−Lin−GFP+ progenitor cells transduced with either vector alone, WT, or mutant forms of Lnk, and WT APS and subjected to RT-PCR with specific primers for Lnk and APS (top panels) or HPRT (bottom panels) as control. (B-C) WT or Lnk−/−Lin−GFP+ transduced cells were assessed for their in vitro colony-forming ability of multilineage (B) or megakaryocytic (C) progenitors in methylcellulose media containing optimal concentrations of appropriate recombinant growth factors. Data represent the mean ± SD (error bars) of number of colonies/103 (for CFU-GEMM) or 1.5 × 104 (for CFU-Meg) Lin−GFP+ cells from triplicate samples from 3 independent assays using 3-5 mice of each genotype. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test: *P ≤ .002; **P ≤ .02; ***P ≤ .01. CFU-GEMM, colony-forming unit of granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, and megakaryocyte cells; CFU-Meg, colony-forming unit of megakaryocyte cells.

Lnk domains and Y537 contribute differently to the expansion of myeloid and megakaryocytic progenitors. (A) Schematic representation of WT and Lnk mutant forms cloned into the MIG retroviral vector. Point mutations in the PH domain (W270A), SH2 domain (R364M), and in the C-terminal tyrosine (Y536F) are indicated with an asterisk (*) or F. Total RNA was extracted from WT (+/+) or Lnk−/−Lin−GFP+ progenitor cells transduced with either vector alone, WT, or mutant forms of Lnk, and WT APS and subjected to RT-PCR with specific primers for Lnk and APS (top panels) or HPRT (bottom panels) as control. (B-C) WT or Lnk−/−Lin−GFP+ transduced cells were assessed for their in vitro colony-forming ability of multilineage (B) or megakaryocytic (C) progenitors in methylcellulose media containing optimal concentrations of appropriate recombinant growth factors. Data represent the mean ± SD (error bars) of number of colonies/103 (for CFU-GEMM) or 1.5 × 104 (for CFU-Meg) Lin−GFP+ cells from triplicate samples from 3 independent assays using 3-5 mice of each genotype. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test: *P ≤ .002; **P ≤ .02; ***P ≤ .01. CFU-GEMM, colony-forming unit of granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, and megakaryocyte cells; CFU-Meg, colony-forming unit of megakaryocyte cells.

Expression of WT Lnk reestablished normal numbers of CFU-GEMM colonies in Lnk−/− progenitors similarly to Lin− cells derived from wild-type animals. Expression of either PH inactive (W270A) form or Lnk mutated at the C-terminal tyrosine (Y536F), moderately reestablished multilineage colony numbers in contrast to the R364M mutant protein (Figure 7B). This result shows that the SH2 domain is important for inhibiting multilineage cell growth. In this context, the adaptor APS could not replace Lnk function at the progenitor level.

In contrast to CFU-GEMM, analysis of CFU-Meg colonies showed that the R364M mutant displayed a similar effect as the W270A form (Figure 7C). Together, these results indicate that the individual domains and Y536 of Lnk contribute differently to its inhibitory function during expansion of multilineage and megakaryocytic progenitors.

Discussion

Lnk-deficient mice display a phenotype reminiscent of MPNs that has suggested a role for Lnk in the development of these diseases. Recently, the first Lnk mutations in ET and PMF patients have been identified.25 We confirm that the prevalence of such mutations is rare (5% or less) in JAK2-WT ET patients and therefore, the significance of Lnk mutations in MPN pathogenesis remains unclear. In this study, we have addressed the question of other mechanisms accounting for abnormal Lnk function by analyzing cells derived from MPN patients, Lnk−/− progenitors and hematopoietic cell lines expressing WT or mutated forms of either JAK2 or Lnk. Our results show that Lnk expression is up-regulated by the TPO/MPL/JAK2 pathway in megakaryocytic and MPN primary cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate that changes in the level of Lnk expression and in its binding to JAK2-V617F can modulate the responses mediated by the JAK2 forms expressed in these diseases.

Our previous analyses of Lnk−/− mice suggested tight regulation of Lnk during hematopoiesis.21 In the present work, we found that Lnk mRNA and protein expression were regulated by TPO-activated signaling pathways in megakaryocytic cells. This was further confirmed in platelets isolated from RT patients, which are often associated with elevated TPO levels.26 Consistent with our results, recent studies have demonstrated that LNK expression is regulated by early-acting (Stem Cell Factor and TPO) and lineage-specific (EPO) growth factors, cytokine receptors (MPL) and JAK2 signaling pathways in HSC, bone marrow cells and hematopoietic cell lines.12,18,19,30,31 Furthermore, the Lnk protein was shown to down-regulate MPL, EPO receptor, and JAK2 kinase signaling after TPO and EPO stimulation, respectively.16,17 Altogether, these results place Lnk as part of an important negative regulatory loop (cytokine receptor/JAK2 kinase/Lnk regulator) in hematopoiesis. Similarly, the SOCS family of negative regulators is induced by the JAK/STAT pathway upon cytokine receptor stimulation. It thereafter acts within a classical negative feedback loop both to suppress activation of the receptor and JAK2 and to target them for proteasomal degradation.32 These parallels indicate that hematopoietic negative regulators exert their function through finely controlled processes that allow precise modulation of the cell's intrinsic sensitivity to cytokines.

Some of the cytokine signaling pathways that regulate Lnk are also deregulated in MPNs, suggesting that the expression and function of Lnk could be affected in these disorders. Indeed, we found that LNK mRNA expression was significantly increased in all MPNs examined (ET, PV, PMF) and notably in JAK2-V617F patients, where LNK overexpression correlated with a higher JAK2-V617F allele burden and JAK2 activity. However, how JAK2 expressed in MPN cells can surmount Lnk inhibition is still unclear. Moreover, this observation seems to contrast with the Lnk inhibition of JAK2-V617F–dependent signaling and proliferation, we and others have shown in hematopoietic cell lines (this work and19,30 ). This apparent paradox can be explained by the fact that the ratio of expression level of JAK2-V617F in respect to Lnk may be different between MPN cells and hematopoietic cell lines, thus modulating Lnk inhibitory function. In the initial phase of MPNs, a low ratio of mutant JAK2/Lnk may be present (JAK2-V617F heterozygous state). In this context, low signaling through JAK2-V617F would induce Lnk, which would then down-regulate JAK2-WT, rather than JAK2-V617F signaling. This would increase the ratio JAK2-V617F/Lnk, but would maintain the proliferative advantage of V617F-expressing cells. In hematopoietic cell lines (homozygous for JAK2-V617F or exogenously expressing it), the initial ratio JAK2-V617F/Lnk is very low because of overexpression of Lnk. This allows the adaptor to down-regulate JAK2, and other signaling effectors (such as MAPK). The subsequent reduction in Lnk expression inversely changes the JAK2-V617F/Lnk ratio, thereby abolishing inhibition of V617F-mediated signals just like in MPN cells. Our results on HEL cells expressing different levels of the Lnk protein, together with the phenotype displayed by Lnk+/− mice (intermediate between that of wild-type and homozygous mice),21 support this argument. Alternatively, it is possible that activation of a signaling effector or pathway, other than JAK2 and insensitive to Lnk inhibition, may be responsible for the uncontrolled cellular proliferation in MPNs. Further experiments are required to test whether Lnk dosage in MPN cells would have pathophysiological consequences on these diseases.

Recent studies have shown that LNK mRNA levels were also elevated in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia cells.30 Together with our data on MPNs, these results suggest a relevant role for Lnk in these proliferative hemopathies.

On the other hand, the data on the inhibition of JAK2-V617F–mediated responses suggest that Lnk is an important inhibitor of mutated JAK2, similarly to the JAK/STAT inhibitor SOCS2.33 Interestingly, Lnk and SOCS2 can inhibit cytokine signaling through interaction with both the cytokine receptor and JAK2.11,18,32 In contrast, SOCS3, who acts mainly on the kinase, is unable to inhibit JAK2-V617F, but rather enhances its kinase activity.34 These results suggest that regulation of the mutated JAK2 is complex and that it may require the combination of several inhibitory mechanisms.

Our analysis of JAK2 activation status in MPN platelets has shown a difference between JAK2-WT and JAK2-V617F MPN samples that correlated with the level of Lnk expression in these patients. This suggests a distinct Lnk-mediated regulatory mechanism for each JAK2 form. We and others have shown that Lnk does not significantly inhibit the initial activation of cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, but it rather diminishes the duration of their activation after cytokine stimulation.16,17,21,24 Consisting with this, we have observed a prolonged phosphorylation of JAK2 in V617F-expressing MPN cells at longer TPO-stimulation times that suggests Lnk inability to inhibit the kinase activation (data not shown). As for JAK2-WT MPN patients, the regulation of JAK2 activation appears more complex, possibly involving a molecular event, yet to be characterized, that regulates the kinase activity in these patients.

Several studies have shown that Lnk interacts with phosphorylated WT and V617F JAK2 in hematopoietic cell lines, resulting in the subsequent phosphorylation of the adaptor.11,19,30 Our results showed for the first time that this interaction occurs in platelets derived from RT and MPN (WT and mutated JAK2) patients. Moreover, we found that Lnk binding to activated JAK2 is required for the phosphorylation of the adaptor by the kinase, and this function is dependent on the Lnk SH2 domain. However, the role of Lnk phosphorylation on JAK2 inhibition is still unclear. Interestingly, HEL cells expressing Lnk mutated at Y536 (Y536F) displayed a significant reduction in Lnk phosphorylation and JAK2-V617F down-regulation, suggesting a role for this tyrosine in both JAK2-mediated Lnk phosphorylation and inhibitory function (A.A. and L.V., unpublished data). In addition, our GST pull-down experiments revealed a novel moderate interaction involving the N-terminal region of Lnk that enables it to associate with inactive JAK2. A similar binding site has been reported for SH2-B and APS, the other members of the Lnk family. In these proteins, the second JAK2-binding site includes the PH domain and the PH-SH2 domain linker region and appears to be inhibitory in nature.28,29,35 For the Lnk protein, we showed that this site does not involve the PH domain, contrary to the recent report by Gery et al.19 This discrepancy might be a result of the length of the PH domain fragment used in each study. Furthermore, we observed that in the presence of the V617F mutation, JAK2 binds stronger to this second Lnk site, suggesting that the mutant kinase displays a different affinity for the adaptor than the WT form. It is then conceivable that the change in JAK2 binding affinity for this site may allow a stronger Lnk inhibition of JAK2 at the basal level. However, it will also affect the kinase subsequent interaction with Lnk SH2 domain, resulting in failure to inhibit JAK2-V617F cytokine-mediated activation. Our recent identification of an Lnk mutation in this region further supports this model. Detailed analysis of the amino acids involved in this Lnk/JAK2 interaction may shed light into the molecular mechanism implicated in Lnk-mediated JAK2 inhibition.

Recent studies have suggested that in MPNs, other genetic modifications, like the TET2 gene mutations36 and the newly identified rare mutations in Lnk (this work and25 ), could confer a proliferative advantage to hematopoietic progenitors.37 Interestingly, expression of the JAK2-V617F form in Lnk−/− progenitors increased the number of cytokine-independent colonies in these cells compared with wild-type cells expressing JAK2-V617F and accelerates oncogenic JAK2-induced MPNs in mice.19,38 Together with our data obtained in PMF and PV CD34+ and mature (platelets) cells from MPN patients, these results indicate that Lnk regulation is important during all stages of myeloid differentiation and can contribute to the development of MPNs and probably of other human hematopoietic malignancies.

The studies presented here on Lnk−/−Lin− progenitors expressing either WT or mutant forms of Lnk have helped to better define its inhibitory role in the expansion of hematopoietic progenitors. Indeed, we showed that the SH2 domain contributes mainly to inhibition of the proliferation of multilineage progenitors. In contrast, analysis of megakaryocytic progenitors indicated that both SH2 and PH domains are important for Lnk-mediated growth inhibition of these cells. This function is specific to Lnk because expression of Aps in these cells does not compensate for the lack of Lnk.

In summary, this is the first comprehensive study of the role of Lnk in a representative cohort of MPN patients showing that Lnk levels and JAK2-binding can modulate the cellular responses mediated by the JAK2 forms present in these diseases. In addition, our findings provide evidence that Lnk participates, together with the Mpl receptor and the JAK2 kinase, in a finely controlled feedback mechanism essential for the regulation of TPO-mediated megakaryopoiesis and consequently, thrombopoiesis. Finally, we identified a novel interaction site between Lnk and JAK2, which together with the SH2 domain may play a major role in the down-regulation of both normal and MPN-derived hematopoiesis. Defining the signaling pathways and effectors, other than JAK2, regulated by Lnk will help to better understand the role of this adaptor in the pathogenesis of MPNs and determine its potentially therapeutic value.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who donated their cells to support this research, the PV-Nord group, Nicole Boggetto for assistance with flow cytometry sorting, François Delhommeau for providing CD34+ cells from PV patients, and the sequencing device of Hôpital Henri Mondor (Créteil).

This work was supported by grants from the Institut National de la Santé et la Recherche Médicale (Inserm)–Avenir, the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (LNCC)–Comité St. Denis, the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC), the Association Laurette Fugain, and the Association Nouvelles recherches Biomédicales (NRB). H.M. is the recipient of a PhD scholarship from the Groupe d'Etude sur l'Hémostase et la Thrombose (GEHT). A.A. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Universidad de Guadalajara (Mexico).

Authorship

Contribution: F.B.M. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and contributed to writing the manuscript; H.M., C.D., C.R., and A.A. performed experiments; S.H. collected clinical characteristics from all the patients; E.M. contributed to cellular experiments; S.C. performed statistical analysis; B.C. contributed genotyping analysis; S.G. and C.T. contributed MPL and Lnk sequencing; P.F., F.C., and N.V.B. contributed scientific discussion and reviewed the manuscript; M.C.L.B.K. contributed to the recruitment of patients, interpretation of the data, and writing the paper; J.J.K. contributed to the recruitment of patients, analyzing the data, designing the research and writing the manuscript; and L.V. designed and performed research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.A. is Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico.

Correspondance: Laura Velazquez, UMR U978 Inserm/Université Paris 13, Adaptateurs de Signalisation en Hématologie, UFR SMBH, 74 rue Marcel Cachin, 93 017 Bobigny Cedex, France; e-mail: laura.velazquez@inserm.fr; and Jean-Jacques Kiladjian, Clinical Investigation Center, Hôpital Saint-Louis and French Intergroup of Myeloproliferative Disorders, 1 Avenue Claude Vellefaux, Paris 75010, France; e-mail: jean-jacques.kiladjian@sls.aphp.fr.