Abstract

Type 1 T regulatory (Tr1) cells suppress immune responses in vivo and in vitro and play a key role in maintaining tolerance to self- and non–self-antigens. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is the crucial driving factor for Tr1 cell differentiation, but the molecular mechanisms underlying this induction remain unknown. We identified and characterized a subset of IL-10–producing human dendritic cells (DCs), termed DC-10, which are present in vivo and can be induced in vitro in the presence of IL-10. DC-10 are CD14+, CD16+, CD11c+, CD11b+, HLA-DR+, CD83+, CD1a−, CD1c−, express the Ig-like transcripts (ILTs) ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G antigen, display high levels of CD40 and CD86, and up-regulate CD80 after differentiation in vitro. DC-10 isolated from peripheral blood or generated in vitro are potent inducers of antigen-specific IL-10–producing Tr1 cells. Induction of Tr1 cells by DC-10 is IL-10–dependent and requires the ILT4/HLA-G signaling pathway. Our data indicate that DC-10 represents a novel subset of tolerogenic DCs, which secrete high levels of IL-10, express ILT4 and HLA-G, and have the specific function to induce Tr1 cells.

Introduction

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is an immunomodulatory cytokine that plays a central role in controlling inflammation, down-regulating immune responses, and inducing tolerance.1 IL-10 inhibits proliferation and cytokine production by T cells and down-regulates production of inflammatory cytokines as well as expression of costimulatory molecules on monocytes/macrophages.2 Importantly, IL-10 induces long-lasting antigen (Ag)–specific T-cell anergy and differentiation of type 1 regulatory T (Tr1) cells both in humans3 and mice.4 Tr1 cells are characterized by a unique cytokine production profile: they produce high levels of IL-10, Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β), and IL-5, low levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-2, and no IL-4. Tr1 cells are anergic in vitro and actively suppress immune responses mainly via IL-10 and TGF-β.4 Several protocols have been developed to generate Tr1 cells in vitro and in vivo.5 Although IL-10 has been shown to be indispensable for Tr1 cell induction, it requires the presence of Ag-presenting cells (APCs) in vitro.5,6 In addition to IL-10, it has been shown that other cytokines, such as IFN-α,6 or inhibitory and costimulatory molecules, such as ICOS-L7 and CD46,8 can promote Tr1 cell differentiation. However, it remains to be elucidated whether Tr1 cell induction needs a specialized subset of APCs or may occur when T cells recognize the Ag on professional APCs in the presence of IL-10 or other cytokines produced by the microenvironment.

Several lines of evidence indicate that in vitro T-cell priming by immature DC (iDCs), as well as by DCs rendered tolerogenic with biologic or pharmacologic agents, drives the differentiation of Tr cells.5 We have previously reported that repetitive stimulation of human peripheral blood–naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic iDCs results in differentiation of Tr1 cells, which is IL-10–dependent.9 Indeed, iDCs treated with exogenous IL-10 display a reduced allostimulatory capacity and are shown to induce Ag-specific anergic T cells.10 Furthermore, DCs matured in the presence of exogenous IL-10 induce Ag-specific anergic T cells,11 which suppress T-cell proliferation through a cell-cell contact mechanism.12 However, these protocols to induce Tr1 cells are rather inefficient because repetitive Ag stimulations in the presence of IL-10 were required to generate low frequencies of Tr1 cells. In addition, it was unclear which signaling pathways induced the anergic cells with suppressive function.

The nonclassic Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) class I molecule HLA-G plays a central role in the induction and maintenance of fetal-maternal tolerance during pregnancy.13 HLA-G inhibits cytolytic activities of both NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs),14 and allospecific T-cell proliferation.15 A positive correlation between allograft acceptance and HLA-G expression on both donor cells16 and recipient T cells15 has been reported, indicating a role of HLA-G in modulation of alloresponses. In addition, HLA-G acts as a negative regulator of tumor immune responses through several mechanisms, including inhibition of angiogenesis, prevention of antigen recognition and T-cell migration, and suppression of T and NK cytolytic effects.17 APCs overexpressing HLA-G are poor stimulators and are able to promote the induction of anergic/suppressor CD4+ T cells.18 HLA-G binds to the inhibitory molecules immunoglobulin-like transcript (ILT) ILT2 and ILT4 expressed on DCs.19 The engagement of ILT4 by HLA-G tetramers prevents the up-regulation of costimulatory molecule expression, inhibits DC maturation,20 and promotes the differentiation of anergic/suppressor CD4+ T cells.20,21 IL-10 is one of the key cytokines inducing HLA-G expression on monocytes.22 Recently, it has been reported that, in addition to membrane-bound, also soluble HLA-G plays a role in promoting the induction of CD4+ suppressor cells.23 Interestingly, recently a subset of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing HLA-G has been described, which are anergic and suppress T-cell responses in vitro.24

In the present study, we identify and characterize a subset of tolerogenic DCs (DC-10), which occur in vivo, secrete high levels of IL-10, but no IL-12, and are potent inducers of Tr1 cells in vitro. Importantly, we demonstrate that these DC-10 drive Tr1 cell differentiation via the IL-10–dependent ILT4/HLA-G pathway.

Methods

Data regarding methods are reported in full in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Peripheral blood was obtained on informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under protocols approved by the ethical committee of the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy.

DC isolation

DC-10 were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) sorting. Myeloid cells were enriched by selective depletion of CD3 and CD19 cells (Oxoid) and incubated for 15′ at room temperature with antihuman CD11c, CD14, and CD83 monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) in RPMI containing 2% fetal calf serum, and then FACS sorted. DC-10 were CD14+CD11c+CD83+, whereas myeloid DCs (myDCs) were CD14−CD11c+CD83+.

Results

DC-10 are a unique subset of DCs

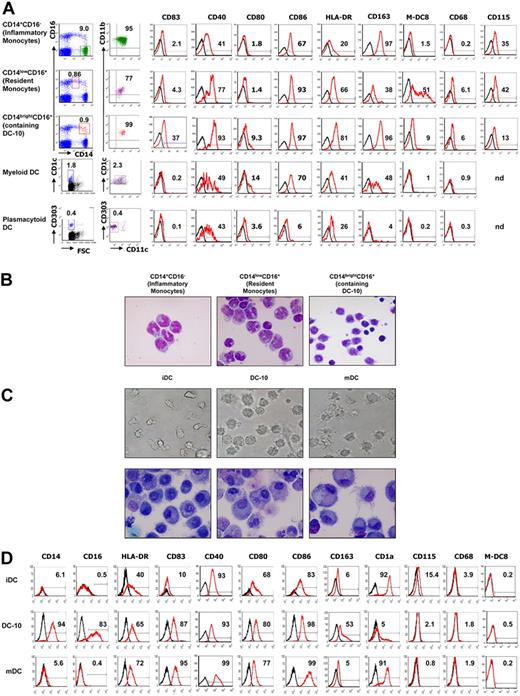

DC-10 were identified in peripheral blood of healthy donors where they represent 0.3% plus or minus 0.18% (mean ± SD, n = 10) of the mononuclear cells (Figure 1A). A comparative analysis of the expression of CD40, CD68, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, M-DC8, CD115, and CD163 among CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10), myDCs (CD11c+CD1c+), and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs, CD11c−CD303+) revealed that DC-10 represent a subpopulation of cells (∼ 30%) composed of the CD14brightCD16+ subset, which express CD83 on the cell surface. DC-10 are CD14brightCD16+CD11c+CD11b+ and express CD40, CD83, CD86, and HLA-DR but not CD1a, CD1c, and CD68 (Figure 1A and data not shown). A proportion of peripheral DC-10 express also CD80. The expression of the hemoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 by DC-10 was similar to that observed in inflammatory monocytes; but in contrast to them, DC-10 are CD16+, expressed higher levels of HLA-DR, and express CD83. In contrast to resident monocytes, DC-10 do not express M-DC8,25 and express CD115 at lower levels (Figure 1A). The phenotype of DC-10 differ from that of myDCs because they are CD1c−CD14bright, and that of pDC because they are CD303−CD11c+CD14bright and express HLA-DR, CD83, and CD86. DC-10 express CCR2, CCR4, CCR9, and CX3CR1 (supplemental Figure 1). DC-10 express both CCR2 and CX3CR1 in contrast to CD14+CD16− inflammatory monocytes, and CD14lowCD16+ resident monocytes, which express CCR2 and CX3CR1, respectively. Importantly, DC-10 express significant levels of CCR9, the gut-homing receptor.26

DC-10 are present in peripheral blood and can be differentiated in vitro from peripheral monocytes. (A) Expression levels of CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD16, CD40, CD68, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, CD115, CD163, and M-DC8 in gated CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10), myDCs (CD1c+CD11c+), and pDCs (CD11c−CD303+) in peripheral blood were evaluated by FACS analysis. Black histograms represent staining with the isotype-matched control mAbs. A representative donor of 10 independent donors analyzed is presented. Percentages of CD14+CD16−, CD14lowCD16+, CD14brightCD16+, CD1c+CD11c+, CD303+CD11c− cells in total peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and percentages of CD14+CD16−, CD14lowCD16+, CD14brightCD16+, CD1c+CD11c+, CD303+CD11c− cells expressing the indicated markers are indicated. (B) Morphology (May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining) of CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10) FACS-sorted from peripheral blood. Results from one representative donor of 2 tested is shown. (C) Monocyte-derived DCs were differentiated in IL-4 and GM-CSF in the presence of IL-10 for 7 days (DC-10), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 7 days (iDC), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 5 days and activated for additional 2 days with LPS (mDC). Morphology of DCs was evaluated by light microscopy and by May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Results from one representative donor of 5 tested is shown. Image information: Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope; magnification 40×/0.55; cover slides were mounted using DXP (water free mounting medium); Nikon DXM1200 camera; Nikon ACT-1 Version 2.63 and PowerPoint software. (D) Expression of CD14, CD16, HLA-DR, CD40, CD83, CD80, CD86, CD163, CD1a, CD115, CD68, and M-DC8 was evaluated by FACS analysis. A representative donor of at least 15 tested is presented.

DC-10 are present in peripheral blood and can be differentiated in vitro from peripheral monocytes. (A) Expression levels of CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD16, CD40, CD68, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, CD115, CD163, and M-DC8 in gated CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10), myDCs (CD1c+CD11c+), and pDCs (CD11c−CD303+) in peripheral blood were evaluated by FACS analysis. Black histograms represent staining with the isotype-matched control mAbs. A representative donor of 10 independent donors analyzed is presented. Percentages of CD14+CD16−, CD14lowCD16+, CD14brightCD16+, CD1c+CD11c+, CD303+CD11c− cells in total peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and percentages of CD14+CD16−, CD14lowCD16+, CD14brightCD16+, CD1c+CD11c+, CD303+CD11c− cells expressing the indicated markers are indicated. (B) Morphology (May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining) of CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10) FACS-sorted from peripheral blood. Results from one representative donor of 2 tested is shown. (C) Monocyte-derived DCs were differentiated in IL-4 and GM-CSF in the presence of IL-10 for 7 days (DC-10), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 7 days (iDC), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 5 days and activated for additional 2 days with LPS (mDC). Morphology of DCs was evaluated by light microscopy and by May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Results from one representative donor of 5 tested is shown. Image information: Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope; magnification 40×/0.55; cover slides were mounted using DXP (water free mounting medium); Nikon DXM1200 camera; Nikon ACT-1 Version 2.63 and PowerPoint software. (D) Expression of CD14, CD16, HLA-DR, CD40, CD83, CD80, CD86, CD163, CD1a, CD115, CD68, and M-DC8 was evaluated by FACS analysis. A representative donor of at least 15 tested is presented.

Morphologic analysis of FACS-sorted cells (Figure 1B) showed that CD14brightCD16+ subset containing DC-10 is a heterogeneous cell population with typical monocyte (cells with kidney-shaped nucleus and large cytoplasm) or DC morphology (with rounded nucleus, large cytoplasm, and dendrites). As expected, CD14lowCD16+ and CD14+CD16− monocytes are homogeneous cell populations (> 90% of the cells with kidney-shaped nucleus and large cytoplasm). The cell morphology confirmed the findings that DC-10 are a subpopulation of DCs contained in the CD14brightCD16+ cell subset.

To determine whether DC-10 reside also in secondary lymphoid organs, we analyzed their frequency in the spleen of cadaveric healthy donors. Using CD14, CD11b, CD11c, CD83, and CD1c as markers, we demonstrated that DC-10 cells are present in human spleen and represent 3.1% plus or minus 1.3% (mean ± SD, n = 6) of the total cells. Similarly to peripheral DC-10, DC-10 in the spleen express CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, and CD80 at low levels and do not express M-DC8 (supplemental Figure 2).

DC-10 can also be differentiated by culturing monocytes with IL-4, GM-CSF, and IL-10 for 7 days. The resulting DC-10 display large and granular morphology and lower number of dendrites compared with mature DCs (mDCs) (Figure 1C). Giemsa staining shows that in vitro differentiated DC-10 are larger compared with monocyte-derived immature DCs and have a rounded nucleus with large cytoplasm. However, monocyte-derived DC-10 have less pronounced dendrites compared with monocyte-derived mature DC (Figure 1C).

Similar to peripheral DC-10, monocyte-derived DC-10 are CD14+CD16+CD11c+CD11b+CD1a−CD1c−CD68− (Figure 1D; Table 1; and data not shown). Although not activated, monocyte-derived DC-10 express levels of HLA-DR, CD40, CD80, CD83, and CD86 similar to those of mDCs, which were activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Figure 1D; Table 1). DC-10 do not express CD115 and M-DC8. DC-10, but not iDCs and mDCs, express high levels of CD163. Monocyte-derived DC-10 are distinct from the previously described IL-10–treated monocyte-derived DCs, generated in vitro by addition of exogenous IL-10 during the last 2 days of differentiation, which are CD14− and down-regulate CD80, CD83, CD86, and HLA-DR10 (supplemental Figure 3).

Thus, the differentiation of DCs from monocytes in the presence of exogenous IL-10 results in a subset of DCs different from iDCs, mDCs, and IL-10–treated DCs, which is comparable with DC-10 detected in peripheral blood in vivo.

DC-10 sorted from peripheral blood of healthy donors, according to the expression of CD11c, CD14, and CD83, and activated with zymosan, poly(I:C), and LPS secrete significantly higher levels of IL-10 compared with both CD14+ cells and myDCs. Activation of peripheral DC-10 with poly(I:C) and LPS results in significantly lower production of IL-12 compared with myDCs (Figure 2A). Peripheral DC-10 activated with zymosan, poly(I:C), and LPS secrete IL-6 and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) at levels comparable with those produced by activated CD14+ cells and myDCs (Figure 2A). Monocyte-derived DC-10 also secrete high amounts of IL-10 and IL-6 and no IL-12 (Figure 2B). On activation with LPS and IFN-γ, DC-10 maintain the IL-10 and IL-6 production but do not secrete significant levels of IL-12 and secrete low levels of TNF-α, whereas activated iDCs produce high amounts of IL-10, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α (Figure 2B). These results, which were confirmed at the mRNA levels (data not shown), indicate that monocyte-derived DC-10 do not change their phenotype on activation and maintain their ability to express and secrete IL-10 and IL-6 but low IL-12 and TNF-α. mDCs did not significantly increase the levels of IL-12 and TNF-α production on secondary stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ because of exhaustion in vitro (Figure 2B).

DC-10 produce high levels of IL-10 but low amounts of IL-12. (A) DC-10 or myDCw FACS-sorted from peripheral blood according to CD11c, CD83, and CD14 expression were activated with zymosan, poly(I:C), LPS, flagellin, and CpG. As control, sorted CD14+ cells were used. Culture supernatants were collected after 48 hours, and levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNF-α were determined by Bioplex. The average ± SD levels of cytokines detected in 3 independent experiments are presented. *P ≤ .05, freshly isolated DC-10 vs freshly isolated myDCs or to CD14+ cells. (B) Monocyte-derived DCs were differentiated in IL-4 and GM-CSF in the presence of IL-10 for 7 days (DC-10), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 7 days (iDC), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 5 days and activated for additional 2 days with LPS (mDC). iDCs, DC-10, and mDC were cultured in medium or activated with IFN-γ and LPS for additional 2 days and levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNF-α in culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. The mean ± SEM levels of cytokines detected in 17 independent experiments are presented. **P ≤ .005, ***P < .001, DC-10 vs both iDCs and mDCs.

DC-10 produce high levels of IL-10 but low amounts of IL-12. (A) DC-10 or myDCw FACS-sorted from peripheral blood according to CD11c, CD83, and CD14 expression were activated with zymosan, poly(I:C), LPS, flagellin, and CpG. As control, sorted CD14+ cells were used. Culture supernatants were collected after 48 hours, and levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNF-α were determined by Bioplex. The average ± SD levels of cytokines detected in 3 independent experiments are presented. *P ≤ .05, freshly isolated DC-10 vs freshly isolated myDCs or to CD14+ cells. (B) Monocyte-derived DCs were differentiated in IL-4 and GM-CSF in the presence of IL-10 for 7 days (DC-10), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 7 days (iDC), or in IL-4 and GM-CSF for 5 days and activated for additional 2 days with LPS (mDC). iDCs, DC-10, and mDC were cultured in medium or activated with IFN-γ and LPS for additional 2 days and levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNF-α in culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. The mean ± SEM levels of cytokines detected in 17 independent experiments are presented. **P ≤ .005, ***P < .001, DC-10 vs both iDCs and mDCs.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that DC-10, which are present in vivo and are inducible in vitro from peripheral monocytes in the presence of exogenous IL-10, represent a DC subset with an unique cytokine production profile characterized by a high ratio of IL-10/IL-12 production.

DC-10 display low stimulatory capacity and induce T-cell anergy

Naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with allogeneic peripheral DC-10, at 10:1 ratio, resulted in a significantly lower proliferative response with a reduction in proliferation of 74% plus or minus 19% (mean ± SD, n = 7) compared with naive CD4+ T cells primed with myDCs (Figure 3A). Similarly, IFN-γ production by naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with allogeneic peripheral DC-10 was reduced compared with production by naive CD4+ T cells primed with myDCs (data not shown). Notably, at 1:1 ratio, naive CD4+ T cells activated with peripheral allogeneic DC-10 showed a proliferative response, which was lower compared with naive T cells activated with myDCs but significantly higher to that of cells stimulated with CD14+CD16− (inflammatory monocytes) or CD14lowCD16+ (resident monocytes) antigen-presenting cells (supplemental Figure 4). These results sustained the hypothesis that peripheral DC-10 represent a subpopulation of DCs.

DC-10 display low stimulatory capacity and induce T-cell anergy. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic DC-10 or myDCs, isolated from peripheral blood by FACS sorting according to the expression of CD11c, CD83, and CD14, at the ratio of 10:1. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation for an additional 16 hours. (B) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with monocyte-derived allogeneic iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs at the ratio of 10:1. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation for an additional 16 hours. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with peripheral allogeneic DC-10 [T(DC-10)] or myDCs [T(myDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to monocytes from the same allogeneic donor. Proliferative responses were evaluated 2 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs from the same allogeneic donor. Proliferative responses were evaluated 2 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (E) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to tetanus toxoid and Candida albicans. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Results of 1 representative experiment of 7 (A), 24 (B,D), 6 (C), and 3 (E) independent experiments performed are shown. Numbers represent the percentage of inhibition of proliferation of T cells primed with freshly isolated DC-10 compared with proliferation of T cells stimulated with peripheral myDCs (A), or of T cells primed with monocyte-derived iDCs or DC-10 compared with proliferation of T cells stimulated with monocyte-derived mDC (B). The percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) cells compared with T(myDC) cells (C), and of T(iDC) or T(DC-10) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (D) is also indicated. *P ≤ .005, **P ≤ .005, CD4+ T cells primed with DC-10 vs naive CD4+ T cells primed with myDCs or iDCs (A-B), and T(DC-10) cells vs T(iDC) or T(myDC) cells (C-D).

DC-10 display low stimulatory capacity and induce T-cell anergy. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic DC-10 or myDCs, isolated from peripheral blood by FACS sorting according to the expression of CD11c, CD83, and CD14, at the ratio of 10:1. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation for an additional 16 hours. (B) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with monocyte-derived allogeneic iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs at the ratio of 10:1. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation for an additional 16 hours. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with peripheral allogeneic DC-10 [T(DC-10)] or myDCs [T(myDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to monocytes from the same allogeneic donor. Proliferative responses were evaluated 2 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs from the same allogeneic donor. Proliferative responses were evaluated 2 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (E) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to tetanus toxoid and Candida albicans. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Results of 1 representative experiment of 7 (A), 24 (B,D), 6 (C), and 3 (E) independent experiments performed are shown. Numbers represent the percentage of inhibition of proliferation of T cells primed with freshly isolated DC-10 compared with proliferation of T cells stimulated with peripheral myDCs (A), or of T cells primed with monocyte-derived iDCs or DC-10 compared with proliferation of T cells stimulated with monocyte-derived mDC (B). The percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) cells compared with T(myDC) cells (C), and of T(iDC) or T(DC-10) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (D) is also indicated. *P ≤ .005, **P ≤ .005, CD4+ T cells primed with DC-10 vs naive CD4+ T cells primed with myDCs or iDCs (A-B), and T(DC-10) cells vs T(iDC) or T(myDC) cells (C-D).

Stimulation of naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic monocyte-derived DC-10 also resulted in a significantly lower proliferative response (with a reduction in proliferation of 85% ± 17%, mean ± SD, n = 24, compared with naive CD4+ T cells primed with mDCs, Figure 3B). As previously reported,9 iDCs also poorly stimulated allogeneic naive CD4+ T cells (mean ± SD reduction in proliferation of 65% ± 22%, n = 24, compared with proliferation induced by mDC). However, the stimulatory capacity of DC-10 was significantly reduced compared with that of iDCs (n = 24, P < .001). Similarly, IFN-γ production by naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived DC-10 was reduced compared with production by naive CD4+ T cells primed with mDCs and was significantly lower than that induced by iDCs (mean ± SD reduction of 88% ± 14% vs 61% ± 30% with DC-10 and iDCs, respectively, n = 8, P = .035, data not shown). DC-10 activated with IFN-γ and LPS maintained their reduced stimulatory capacity. T-cell proliferation induced by activated DC-10 was significantly reduced compared with that of T cells stimulated with activated iDCs (mean ± SD reduction of 89% ± 8% vs 4% ± 6% with DC-10 and iDCs, respectively, n = 4, P < .001; supplemental Figure 5). Activated iDCs acquired a mature phenotype and induced a proliferation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells, which was similar to that induced by mDCs (supplemental Figure 5). These data show that DC-10, on the contrary to iDCs, maintain their low stimulatory capacity even on activation.

To investigate the function of T cells primed with DC-10, secondary responses were assessed. After one round of stimulation, T cells primed with peripheral DC-10, T(DC-10), were unable to proliferate when restimulated with monocytes from the same donor (Figure 3C). Similarly, T cells activated with allogeneic monocyte-derived DC-10 were profoundly hyporesponsive to reactivation with mDCs. Conversely, T cells stimulated with iDCs, T(iDCs), display significant proliferation (Figure 3D). IFN-γ production by T cells generated with either peripheral or monocyte-derived DC-10 and rechallenged with monocytes or mDCs was also reduced (data not shown). T-cell anergy observed in T(DC-10) cell lines was reversed by the addition of IL-2 (supplemental Figure 6). Although peripheral DC-10 induced a significantly lower T-cell proliferation compared with that of monocyte-derived DC-10, they both promoted T-cell anergy. Importantly, T cells generated with monocyte-derived DC-10 were anergic toward the allo-Ags expressed by the DC-10 used for their priming but preserved their ability to proliferate in response to nominal Ags, such as tetanus toxoid and Candida albicans (Figure 3E) and to third-party allo-Ags (data not shown). In conclusion, Ag-specific T-cell anergy is induced in naive CD4+ T cells activated by Ags presented by either peripheral or monocyte-derived DC-10.

DC-10 induce the differentiation of IL-10–producing Tr1 cells

T cells obtained after one round of stimulation with DC-10, T(DC-10), contained a significant proportion of IL-10–producing cells (average, 8%, n = 9) and a low proportion of IL-4-producing cells (average, 4%). In these culture conditions, IL-2-producing cells were on average 7%, and IFN-γ-producing cells were on average 16%. Conversely, cultures of T cells differentiated with iDCs or mDCs contained more IFN-γ-producing cells (on average, 23% and 40%, with iDCs and mDCs, respectively) and less IL-10–producing cells (on average, 2.6% and 2.7% with iDCs and mDCs, respectively). Overall, the frequency of IL-10–producing cells was significantly higher in T(DC-10) cells, compared with T(iDCs) and T(mDC) cells (P = .001; Figure 4).

DC-10 induce Tr1 cells. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)] for 14 days. After stimulation, T cells were activated with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb and phorbol myristate acetate (TPA), and cytokine production was determined by intracytoplasmic staining and cytofluorometric analysis. (A) One representative experiment of 9 performed is presented. (B) Percentages of IFN-γ–, IL-2–, IL-4–, and IL-10–producing cells in T(iDC), T(DC-10), and T(mDC) cells generated from each of the 9 donors tested are presented. ***P ≤ .001, IL-10 production by T(DC-10) cells vs T(iDC) cells. °°P ≤ .01, °°°P ≤ .001, IL-10, IL-2, and IFN-γ production by T(DC-10) cells vs T(mDC) cells.

DC-10 induce Tr1 cells. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)] for 14 days. After stimulation, T cells were activated with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb and phorbol myristate acetate (TPA), and cytokine production was determined by intracytoplasmic staining and cytofluorometric analysis. (A) One representative experiment of 9 performed is presented. (B) Percentages of IFN-γ–, IL-2–, IL-4–, and IL-10–producing cells in T(iDC), T(DC-10), and T(mDC) cells generated from each of the 9 donors tested are presented. ***P ≤ .001, IL-10 production by T(DC-10) cells vs T(iDC) cells. °°P ≤ .01, °°°P ≤ .001, IL-10, IL-2, and IFN-γ production by T(DC-10) cells vs T(mDC) cells.

The percentage of CD25+FOXP3+ cells was similar in T(DC-10), T(iDCs), and T(mDC) cells (average of 76% ± 12%, 71% ± 6%, and 77% ± 11% respectively, data not shown). Similarly, the percentage of T cells expressing CD122, CD132, IL-15Rα, and CTLA-4 was comparable among T cells generated with different DCs, but T(DC-10) cells express higher levels of CTLA-4 (data not shown). Interestingly, the percentage of T cells expressing granzyme B was also higher in T(DC-10) cells compared with that observed in T(iDCs) and T(mDC) cells, whereas the percentage of T cells expressing granzyme A was comparable among the 3 T-cell populations (data not shown).

Anergic T cells generated with peripheral DC-10 (Figure 5A-B) or with in vitro differentiated DC-10 (Figure 5C-D) suppress primary T-cell responses. Proliferation and IFN-γ production by naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with mDCs (Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction [MLR]) were significantly reduced by addition of T(DC-10) cells at 1:1 ratio. The ability of T(DC-10) cells to suppress naive MLR at only 1:1 Teffector/Tregulatory cell ratio is probably the result of the low frequency of IL-10–producing cells in T(DC-10) cell cultures (supplemental Figure 7). Interestingly, T cells activated with DC-10 acquired suppressive function after a single stimulation, whereas T cells obtained after one round of stimulation with iDCs did not suppress primary MLR (Figure 5C-D). These findings indicate that both peripheral and in vitro induced DC-10 potently promote the induction of anergic T cells with suppressive activity.

DC-10 induce Tr1 cell with suppressive activity. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic DC-10 [T(DC-10)] or myDCs [T(myDC)] isolated from peripheral blood by FACS sorting according to the expression of CD11c, CD83, and CD14, at the ratio of 10:1. After 14 days, T cells were tested for their ability to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with monocytes (MLR). Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocytes alone (MLR) or in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(myDC) cell lines at a 1:1 ratio. As control, T(DC-10) or T(myDC) cell lines were stimulated with monocytes. [3H]-thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Suppression of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in response to monocytes was measured in culture supernatants after 4 days of culture. Results representative of 2 independent experiments are shown. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days, T cells were tested for their ability to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR). Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs alone (MLR) or in the presence of T(iDC), T(DC-10), and T(mDC) cells at a 1:1 ratio. [3H]-Thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 8 independent experiments are shown. (D) Suppression of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in response to mDCs was measured in culture supernatants after 4 days of culture. Results representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Role of IL-10 and TGF-β in suppression mediated by T(DC-10) cells. After activation with DC-10, T(DC-10) cells were tested for their ability to suppress the IFN-γ production of CD4+ T cells in response to allogeneic monocytes in the absence or presence of anti–IL-10R (30 μg/mL) and anti–TGF-β (50 μg/mL) mAbs. Suppression of IFN-γ production was measured in culture supernatants 4 days after culture. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Autocrine IL-10 is required for the differentiation of T(DC-10) cells by DC-10. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic DC-10 in the presence of anti-IL10R (10 μg/mL) or control IgG (10 μg/mL) mAbs. After activation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to suppress the response of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. Numbers represent the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) compared with MLR alone.

DC-10 induce Tr1 cell with suppressive activity. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic DC-10 [T(DC-10)] or myDCs [T(myDC)] isolated from peripheral blood by FACS sorting according to the expression of CD11c, CD83, and CD14, at the ratio of 10:1. After 14 days, T cells were tested for their ability to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with monocytes (MLR). Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocytes alone (MLR) or in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(myDC) cell lines at a 1:1 ratio. As control, T(DC-10) or T(myDC) cell lines were stimulated with monocytes. [3H]-thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Suppression of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in response to monocytes was measured in culture supernatants after 4 days of culture. Results representative of 2 independent experiments are shown. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days, T cells were tested for their ability to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR). Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs alone (MLR) or in the presence of T(iDC), T(DC-10), and T(mDC) cells at a 1:1 ratio. [3H]-Thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 8 independent experiments are shown. (D) Suppression of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in response to mDCs was measured in culture supernatants after 4 days of culture. Results representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Role of IL-10 and TGF-β in suppression mediated by T(DC-10) cells. After activation with DC-10, T(DC-10) cells were tested for their ability to suppress the IFN-γ production of CD4+ T cells in response to allogeneic monocytes in the absence or presence of anti–IL-10R (30 μg/mL) and anti–TGF-β (50 μg/mL) mAbs. Suppression of IFN-γ production was measured in culture supernatants 4 days after culture. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Autocrine IL-10 is required for the differentiation of T(DC-10) cells by DC-10. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic DC-10 in the presence of anti-IL10R (10 μg/mL) or control IgG (10 μg/mL) mAbs. After activation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to suppress the response of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. Numbers represent the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) compared with MLR alone.

T cells generated with DC-10 suppress primary MLR via an IL-10– and TGF-β-mediated mechanism because both suppression of IFN-γ production and proliferation were completely reversed by the addition of neutralizing anti–IL-10R and anti–TGF-β mAbs (Figure 5E; and data not shown). In addition, T(DC-10) cells do not require cell-cell contact for their suppressive activity because suppression of MLR was observed in experiments performed using transwell chambers (data not shown). Overall, these data indicate that Tr cells generated by DC-10 are functionally equivalent to Tr1 cells.

DC-10 promote Tr1 cell differentiation via IL-10 because naive CD4+ T cells stimulated with DC-10 in the presence of neutralizing anti–IL-10R mAb were not anergic (data not shown) and did not acquire suppressive activity (Figure 5F).

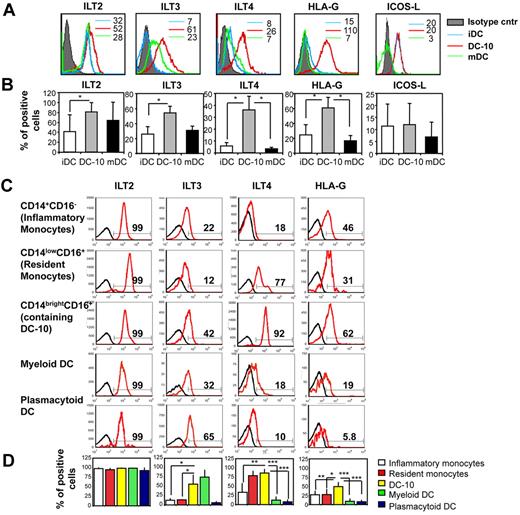

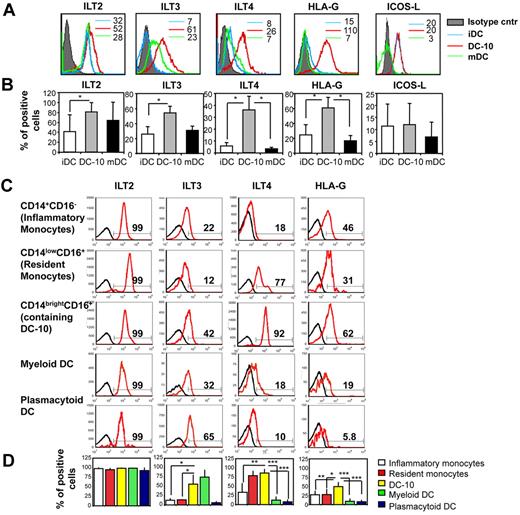

Differentiation of Tr1 cells by DC-10 requires the ILT4/HLA-G pathway

Differentiation of Tr1 cells depends on signaling through the IL-10 functional receptor, which consists of a dimer of IL-10R1 and IL-10R2. This functional receptor is expressed on a large number of cells, including Th2 cells, which, however, do not differentiate into Tr1 cells in the presence of exogenous IL-10.1 This implies that other signaling molecules must be involved in determining the specific differentiation of Tr1 cells from naive T cells. DC-10 expressed significantly higher levels of the tolerogenic molecules ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G compared with iDCs and mDC, whereas ICOS-L was not up-regulated on DC-10 (Figure 6A-B). A comparative analysis of the expression of these markers on CD14brightCD16+ cells, CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), myDCs (CD11c+CD1c+), and pDC (CD11c−CD303+) showed that peripheral CD14brightCD16+ cells expressed high levels of ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G (Figure 6C-D). Expression of ILT4 and HLA-G by DC-10 was significantly higher compared with that on inflammatory and resident monocytes, myDCs, and pDC (Figure 6C-D). Importantly, ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G were also highly expressed on DC-10 in human spleen (supplemental Figure 2).

DC-10 express tolerogenic markers. (A) Monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, HLA-G, and ICOS-L. Numbers represent mean fluorescence intensity. One representative donor of 10 donors analyzed is shown. (B) Mean percentages of positive cells, set according to the isotype-matched controls, gated on CD11c+ cells (not shown), mean ± SD are shown. *P < .01, DC-10 vs iDCs and mDCs. Mean of 10 different donors. (C) DC-10 present in peripheral blood express the tolerogenic markers ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G. Peripheral blood was analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G. Analyses were performed on gated CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10), myDCs (CD1c+CD11c+), and pDCs (CD11c−CD303+). Black histograms represent staining with the appropriate control mAbs. Data from one of 8 independent donors analyzed are presented. Percentages of CD14+CD16−, CD14lowCD16+, CD14brightCD16+, CD1c+CD11c+, CD303+CD11c− cells expressing the indicated markers are shown. (D) Mean percentages of positive cells, set according to the isotype-matched controls (not shown), gated on CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing peripheral DC-10), myDCs (CD1c+CD11c+), and pDCs (CD303+CD11c−), mean ± SD are shown. *P < .01, CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing peripheral DC-10) vs inflammatory and resident monocytes, and to myeloid and pDCs. Data are mean of 8 different donors.

DC-10 express tolerogenic markers. (A) Monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, HLA-G, and ICOS-L. Numbers represent mean fluorescence intensity. One representative donor of 10 donors analyzed is shown. (B) Mean percentages of positive cells, set according to the isotype-matched controls, gated on CD11c+ cells (not shown), mean ± SD are shown. *P < .01, DC-10 vs iDCs and mDCs. Mean of 10 different donors. (C) DC-10 present in peripheral blood express the tolerogenic markers ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G. Peripheral blood was analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G. Analyses were performed on gated CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing DC-10), myDCs (CD1c+CD11c+), and pDCs (CD11c−CD303+). Black histograms represent staining with the appropriate control mAbs. Data from one of 8 independent donors analyzed are presented. Percentages of CD14+CD16−, CD14lowCD16+, CD14brightCD16+, CD1c+CD11c+, CD303+CD11c− cells expressing the indicated markers are shown. (D) Mean percentages of positive cells, set according to the isotype-matched controls (not shown), gated on CD14+CD16− cells (inflammatory monocytes), CD14lowCD16+ cells (resident monocytes), CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing peripheral DC-10), myDCs (CD1c+CD11c+), and pDCs (CD303+CD11c−), mean ± SD are shown. *P < .01, CD14brightCD16+ cells (containing peripheral DC-10) vs inflammatory and resident monocytes, and to myeloid and pDCs. Data are mean of 8 different donors.

ILT4 expressed on DC-10 plays a role in the induction of Tr1 cells because stimulation of naive CD4+ T cells with DC-10 in the presence of neutralizing anti-ILT4 mAb prevented the induction of anergic T cells (Figure 7A) with suppressive activity (Figure 7B). Because ILT4 binds to HLA-G,27 we next investigated the expression of HLA-G on CD4+ T cells activated with DC-10. Naive CD4+ T cells express mean percentage of HLA-G of 2.2% plus or minus 0.9% (mean ± SD, n = 4, data not shown). After priming with DC-10, HLA-G expression by CD4+ T cells was up-regulated and T(DC-10) cells expressed significantly higher levels of HLA-G compared with T cells stimulated with iDCs (18.1% ± 7.1% vs 7.4% ± 2.9%; n = 9, P < .001, Figure 7C). HLA-G expression on T cells stimulated with DC-10 was also higher compared with that observed in T cells stimulated with mDC (11.2% ± 7.0%), but the difference was not significant (n = 9, P = .05). Expression of membrane-bound HLA-G on T cells was confirmed at mRNA levels (data not shown). Importantly, the induction of HLA-G expression on T cells cultured with DC-10 was IL-10 dependent because priming of naive CD4+ T cells with DC-10 in the presence of anti–IL-10R blocking mAb prevented HLA-G up-regulation (Figure 7D). These results indicate that autocrine production of IL-10 by DC-10 not only up-regulates ILT4 and HLA-G on DC, but it is also required for up-regulation of HLA-G on CD4+ T cells.

Role of ILT4/HLA-G interaction in Tr1 cell differentiation. (A-B) Induction of Tr1 cells requires ILT4/HLA-G interaction. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-ILT4 [T(DC-10 anti-ILT4)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (A) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (B). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (A) and 4 days (B) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT4) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (A), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT4) cells compared with MLR alone (B). (C-D) IL-10 induces up-regulation of HLA-G on naive T cells. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs for 48 hours, and T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of HLA-G. Percentages of HLA-G-positive cells obtained by stimulating naive CD4+ T cells with iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs from each of the 10 donors tested are presented. Black lines represent the mean percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs for 48 hours in the presence of control IgG or anti-IL-10R mAbs. T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of HLA-G. Percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells are shown. Black lines represent the mean percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells. (E-F) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-HLA-G [T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (E) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (F). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (E) and 4 days (F) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (E), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G) cells compared with MLR alone (F).(G-H) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-ILT2 [T(DC-10 anti-ILT2)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (G) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (H). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (G) and 4 days (H) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT2) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (G), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT2) cells compared with MLR alone (H).

Role of ILT4/HLA-G interaction in Tr1 cell differentiation. (A-B) Induction of Tr1 cells requires ILT4/HLA-G interaction. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-ILT4 [T(DC-10 anti-ILT4)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (A) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (B). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (A) and 4 days (B) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT4) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (A), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT4) cells compared with MLR alone (B). (C-D) IL-10 induces up-regulation of HLA-G on naive T cells. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs for 48 hours, and T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of HLA-G. Percentages of HLA-G-positive cells obtained by stimulating naive CD4+ T cells with iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs from each of the 10 donors tested are presented. Black lines represent the mean percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs for 48 hours in the presence of control IgG or anti-IL-10R mAbs. T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of HLA-G. Percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells are shown. Black lines represent the mean percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells. (E-F) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-HLA-G [T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (E) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (F). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (E) and 4 days (F) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (E), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G) cells compared with MLR alone (F).(G-H) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-ILT2 [T(DC-10 anti-ILT2)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (G) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (H). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (G) and 4 days (H) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT2) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (G), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT2) cells compared with MLR alone (H).

To prove that ILT4/HLA-G interaction leads to Tr1 cell differentiation driven by DC-10, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with DC-10 in the presence of neutralizing anti–HLA-G mAb. Activation of T cells with DC-10 in the presence of neutralizing anti–HLA-G mAb prevented the induction of anergic T cells (Figure 7E) with suppressive activity (Figure 7F). Importantly, addition of both neutralizing anti-ILT4 and anti–HLA-G mAbs completely abrogated the ability of DC-10 to induce suppressor Tr1 cells (data not shown). We excluded that interaction between HLA-G and ILT2 expressed by DC-10 was required for Tr1 cell induction because stimulation of naive CD4+ T cells with DC-10 in the presence of neutralizing anti-ILT2 mAb did not prevent the induction of Tr1 cells (Figure 7G-H).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that interaction between ILT4 and HLA-G is required for Tr1 cell differentiation. Furthermore, these data show that the indispensable role of IL-10 in Tr1 cell induction is the result of its ability to up-regulate the tolerogenic molecules ILT4 on DC and HLA-G on both DC and T cells.

Discussion

We identify a population of IL-10–producing human DCs (termed DC-10) that is present in vivo both in circulation and in secondary lymphoid organs. DC-10 are CD14+CD16+CD11c+CD11b+HLA-DR+CD83+CD163+CD1a−CD1c−, express high levels of ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G, and secrete IL-10 and IL-6, low levels of TNF-α but no IL-12. DC-10 induce Tr1 cell differentiation in vitro through the ILT4/HLA-G pathway that is dependent on IL-10. Blocking antibodies against IL-10R, ILT4, or HLA-G but not against ILT2 prevent Tr1 cell induction.

This subset of IL-10–producing DCs express markers associated with peripheral blood resident monocytes, including CD14, CD16, and CD115 at low levels, and markers associated with inflammatory monocytes, such as CD14 and CD163, but also markers associated with myDCs, such as CD163. However, in contrast to resident monocytes, CD14brightCD16+ DC-10 express high levels of the IL-10–dependent scavenger receptor CD163 that is expressed also in a subpopulation of DC expressing ILT3, HLA-DR, and CD11c.28 Moreover, DC-10 expressed also significantly higher levels of tolerogenic molecules ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G compared with both resident and inflammatory monocytes, and to classic myDCs. DC-10, although expressing CD14 and CD16, do not express M-DC8, a marker associated with a subset of resident monocytes, termed slan DC.29 Finally, CD14brightCD16+ DC-10 express lower levels of CD115 compared with both resident and inflammatory monocytes. Interestingly, CD14brightCD16+ DC-10 express both CCR2 and CX3CR1, chemokine receptors that distinguish CD14lowCD16+ and CD14+CD16− monocytes, being the former CCR2−CX3CR1+ and the latter CCR2+CX3CR1−.30 Moreover, CD14brightCD16+ DC-10 express CCR9, a gut-homing chemokine receptor.26 These findings, together with the recent observation that cells with DC-10 phenotype are present in the intestinal lamina propria (S.G., D.T., unpublished data, June 2009), suggest that DC-10 have a unique trafficking in vivo.

In contrast to monocytes (both CD14lowCD16+ and CD14+CD16− monocytes), which are not able to promote the proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells, peripheral DC-10 stimulate naive CD4+ T-cell proliferation. However, proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells in response to peripheral DC-10 was significantly lower compared with that elicited by peripheral myDCs. This low proliferative response may be ascribed to the ability of peripheral DC-10 to secrete high levels of IL-10. Peripheral DC-10 display a peculiar cytokine production profile that distinguishes them from monocytes and myDCs. DC-10 secrete high levels of IL-10 on activation of TLR2/TLR6, TLR3, and TLR4 and low amounts of IL-12. It was described that CD14brightCD16+ monocytes (containing CD11c+CD14brightCD16+CD83+ DC-10) are the main producers of IL-10 on activation with LPS and zymosan,31 whereas resident monocytes produce TNF-α and IL-12 in the absence of IL-10, and inflammatory monocytes produce TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-10.32 The ability of peripheral DC-10 to produce cytokines on TLR3 activation indicates that DC-10 express markers associated with CD14brightCD16+ monocyte but are a subpopulation of DCs because TLR3 is specifically expressed by DCs but not by peripheral blood monocytes.33 Therefore, although DC-10 share some common markers with resident and inflammatory monocytes and with myDCs, they represent a population of DCs with a unique phenotype and cytokine production profile.

The role of IL-10 in modulating the in vitro differentiation of monocyte-derived DCs has been previously investigated34-36 with contradictive results. Allavena et al34 demonstrated that IL-10 prevents DC differentiation by promoting a macrophage-like cell phenotype, whereas other studies reported that monocytes treated with IL-10 express markers associated with DCs.35,36 We show that addition of IL-10 during monocyte-derived DC induces DC-10 that express CD14, CD16, and CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86, and HLA-DR, but not CD1a and CD1c. Despite the expression of CD14 and CD16, monocyte-derived DC-10 do not express significant levels of the monocyte marker CD115 and of the macrophage marker CD68, and do not acquire the typical adherent properties of monocytes/macrophages. Moreover, monocyte-derived DC-10 constitutively express CD83 on the surface, irrespectively from activation, and have a DC morphology, including cytoplasmic protrusions. CD83 is a marker specifically associated with DCs,37 which is expressed in the cytoplasm of monocytes, macrophages, and iDCs, and it is rapidly induced on the surface of these cells on activation. In monocytes and macrophages, the up-regulation on activation is transient, whereas stable expression of CD83 is detected on mature DC.38

Peripheral monocytes (CD14+ cells) can differentiate in vitro into type 1 or type 2 macrophages (M1 and M2 cells, respectively) when cultured in the presence of different cytokines.39 Specifically, M2 cells, which share some characteristics with monocyte-derived DC-10, can be generated in vitro by culturing peripheral CD14+ cells in the presence of M-CSF and IL-4, or IL-13 or IL-10.39 Independently from the cytokines used for their generation, M2 cells, in contrast to monocyte-derived DC-10, are adherent cells that express CD68 but not CD40, CD83, and CD86.40,41 Both M2 and monocyte-derived DC-10 secrete high levels of IL-10 and low amounts of IL-1239 ; however, DC-10 secrete significantly levels of IL-6, whereas M2 cells are characterized by low production of IL-6.39,40 Peripheral DC-10 are circulating human DCs, whereas M2 cells are present in virtually all tissues42 where they support Th2-associated effector functions, and participate in the resolution of the inflammation and in tissue repairing.39

In summary, monocyte-derived DC-10 and in vivo isolated DC-10 have a characteristic phenotype and a specific cytokine production profile, which distinguish them from resident and inflammatory monocytes, from iDCs, and myDCs, and from M2 cells. The different levels of expression of CD80 and CD115 in monocyte-derived DC-10, the majority of which are CD80+, and peripheral DC-10, which express CD115, might be the result of different levels of activation, being monocyte-derived DC-10 more activated than peripheral DC-10.

Monocyte-derived DC-10 are different from monocyte-derived DCs matured with IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the presence of IL-1011,12 or from DCs treated with IL-10 during the last 2 days of differentiation (supplemental Figure 3),10 which down-regulate HLA-DR, CD83, and CD86 expression. Monocyte-derived DC-10, in contrast to iDCs, express both CD80 and CD86. The ability of IL-10 to promote the induction of murine tolerogenic DCs has been previously demonstrated. Murine IL-10–induced DCs are characterized by high expression of CD45RB, high secretion of IL-10 on activation, and induction of Ag-specific Tr1 cell differentiation both in vivo and in vitro.43 However, CD45RBhighDCs are different from the human DC-10 described herein because they display a plasmacytoid-like morphology and do not express CD80 and CD86. The observation that a population of DC expressing ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G is present in vivo in peripheral blood and in human spleens further supports the notion that DC-10 represent a subset of tolerogenic DCs, which can play key role in modulating immune responses in vivo by promoting tolerance via Tr1 cell induction.

Differentiation of Tr1 cells with either iDCs9 or immunomodulants, such as IL-10 alone4 or in combination with IFN-α,6 or vitamin D3 and dexamethasone,44 requires repetitive Ag stimulation and results in a low frequency of Tr1 cells in the culture. Conversely, we show that monocyte-derived DC-10 promote the differentiation of IL-10–producing antigen-specific Tr1 cells from naive T cells after a single stimulation. The ability of DC-10 to rapidly induce antigen-specific Tr1 cells is similar to that previously reported by Ito et al for pDCs.45 pDCs activated with CpG express high levels of ICOS-L and induce IL-10–producing Tr cells, which suppress alloresponses in vitro.45 Interestingly, Tr1 cells were induced after a single stimulation not only when allogeneic DC-10 but also when autologous DC-10 pulsed with peptide-allergens (Derp2) were used,46 demonstrating that this culture protocol is efficient also with peptide antigens. These findings are important for the prospective clinical application of Tr1 cells because rapid and efficient ex vivo differentiation combined with Ag specificity are desired characteristics for cellular therapy with Tr cells. The role of IL-10 in promoting the induction of tolerogenic DCs and IL-10–producing Tr cells in vivo has been previously reported in HIV-infected patients.47

The mechanisms underlying Tr1 cell differentiation by tolerogenic DCs are not completely elucidated. We previously demonstrated that autocrine production of low amounts of IL-10 by iDCs, together with repetitive Ag stimulation, is a necessary component of the mechanism.9 Our new data demonstrate that a single stimulation of naive T cells with DC-10 is sufficient to induce human Tr1 cells. This rapid differentiation of Tr1 cells by DC-10 suggests that, in addition to IL-10, other signaling molecules may be involved. In the present study, we show that the autocrine IL-10 production by DC-10 induces the expression of the immunomodulatory molecules ILT4 and HLA-G on DCs. This direct effect of IL-10 in up-regulating ILT4 and HLA-G on DCs is a critical requirement for Tr1 cell induction, as demonstrating by experiments with neutralizing mAbs against ILT4 and HLA-G. Importantly, DC-10 in peripheral blood and spleen express ILT4 and HLA-G, suggesting that this mechanism is also active in vivo.

ILT2, ILT3, and ILT4 belong to a family of Ig-like inhibitory receptors, which mediate inhibition of cell activation, including DCs,27 and play a role in modulating T-cell responses.48 Interestingly, compounds, such as IL-10,4 IFN-α, or vitamin D3,49 which promote anergy and Tr cell differentiation,6,44 also induce up-regulation of ILT3 and ILT4.

HLA-G exerts several immunomodulatory functions, including inhibition of NK and CTL cytolytic activity.14 HLA-G expression is induced after allogeneic transplantation in vivo15 and expression of HLA-G on CD4+ T cells during MLR inhibits allospecific T-cell proliferation,15 suggesting that HLA-G plays a role in modulating alloresponses. HLA-G tetramers bind to CD14lowCD16+ monocytes by interacting with ILT4.19 HLA-G tetramers modulate DC function50 ; and after interaction with ILT4 on DCs, they inhibit their maturation.21 Prevention of maturation of ILT4-expressing DCs by HLA-G tetramers involves IL-6 signaling pathway and STAT3 activation.51 Furthermore, HLA-G-modulated DCs induce suppressor T cells.20,21 In our system, IL-10 promotes up-regulation of membrane-bound HLA-G not only on DC but also on T cells. The role of IL-10 in inducing HLA-G on APCs has been previously shown,22 but this is the first demonstration that IL-10 up-regulates HLA-G expression also on CD4+ T cells. It is possible that HLA-G expression on both DC-10 and CD4+ T cells contributes to Tr1 cell differentiation. The hypothesis that membrane-bound HLA-G expressed by DC-10 is involved in promoting Tr1 cell induction is supported by recent report indicating that T cells primed with HLA-G-expressing APCs or in the presence of soluble HLA-G become suppressor cells.23 HLA-G-induced suppressor T cells are FOXP3−CD4low or CD8low, and suppress via IL-10.23 In addition, a population of CD4+ T cells with regulatory activity, which constitutively express membrane-bound HLA-G, is present both in the thymus and in peripheral blood.24 Suppression mediated by HLA-G+ Tr cells do not require cell-cell contact and is dependent on IL-10 but not TGF-β.52 HLA-G can act as negative signaling molecule in T cells,53 down-regulating proliferation. The finding that expression of HLA-G on T(DC-10) cells is induced by IL-10 is supported by results obtained with human CD4+ T cells transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding for human IL-10. Transduced CD4+ T cells express higher levels of HLA-G than those observed in either untransduced and control vector transduced CD4+ T cells (G. Andolfi, S.G., unpublished data, May 2008). However, the ability of T(DC-10) cells to acquire membrane-bound HLA-G from DC-10 during DC-T coculture cannot be excluded. A cell-to-cell transfer of HLA-G from APCs to T cells is possible.54 Overall, the data indicate that the IL-10–induced HLA-G expression on T cells represents a crucial component in the ILT4-mediated induction of Tr1 cells. It cannot be excluded that additional pathways, such as ILT3-ligand interaction, might synergize with the ILT4/HLA-G interaction in promoting Tr1 cell differentiation.

Based on our results, the following model for tolerance induction can be hypothesized: DC-10 produce IL-10, which inhibits T-cell proliferation and cytokine production, induces HLA-G on T cells, promotes T-cell anergy, and up-regulates ILT2, ILT3, ILT4, and HLA-G on DCs. ILT4/HLA-G interaction and signaling through HLA-G on T cells contribute to T-cell anergy and induction of Tr1 cells. In addition, ILT4/HLA-G interaction in DCs also enhances IL-10 production by DC-10, which amplifies this “tolerogenic” loop by promoting de novo expression of ILT4 and HLA-G on other iDCs (supplemental Figure 8).

In conclusion, our study identifies a subset of tolerogenic DCs, with characteristic phenotype and specific functions, which play a central role in the differentiation of adaptive Tr1 cells via the IL-10–dependent ILT4/HLA-G signaling pathway.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rosa Bacchetta for interesting discussion and helpful suggestions, Eleonora Tresoldi for the technical assistance, and Alessio Palini for cell sorting.

This work was supported by the Italian Telethon Foundation and Cariplo Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: S.G. conceived, designed, coordinated, and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; D.T. and M.S performed research; V.P., M.B., C.F.M., and E.H. performed research and analyzed data; and M.-G.R. conceived and coordinated research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Maria-Grazia Roncarolo, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Via Olgettina 58, Milan, Italy 20132; e-mail: m.roncarolo@hsr.it.

![Figure 3. DC-10 display low stimulatory capacity and induce T-cell anergy. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic DC-10 or myDCs, isolated from peripheral blood by FACS sorting according to the expression of CD11c, CD83, and CD14, at the ratio of 10:1. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation for an additional 16 hours. (B) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with monocyte-derived allogeneic iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs at the ratio of 10:1. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation for an additional 16 hours. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with peripheral allogeneic DC-10 [T(DC-10)] or myDCs [T(myDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to monocytes from the same allogeneic donor. Proliferative responses were evaluated 2 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs from the same allogeneic donor. Proliferative responses were evaluated 2 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (E) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days of culture, T cells were tested for their ability to proliferate in response to tetanus toxoid and Candida albicans. Proliferative responses were evaluated 4 days after culture by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Results of 1 representative experiment of 7 (A), 24 (B,D), 6 (C), and 3 (E) independent experiments performed are shown. Numbers represent the percentage of inhibition of proliferation of T cells primed with freshly isolated DC-10 compared with proliferation of T cells stimulated with peripheral myDCs (A), or of T cells primed with monocyte-derived iDCs or DC-10 compared with proliferation of T cells stimulated with monocyte-derived mDC (B). The percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) cells compared with T(myDC) cells (C), and of T(iDC) or T(DC-10) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (D) is also indicated. *P ≤ .005, **P ≤ .005, CD4+ T cells primed with DC-10 vs naive CD4+ T cells primed with myDCs or iDCs (A-B), and T(DC-10) cells vs T(iDC) or T(myDC) cells (C-D).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/6/10.1182_blood-2009-07-234872/4/m_zh89991055390003.jpeg?Expires=1765031136&Signature=jTxI6NS2MYQG7MKrowCQuSWY8s6obAFWdL9ErFY832sJi3sqz0Wvxi-pLQ0jzuyfOHWYLVjNZMCqcH7uWS86pMiPMyh9tBQcsON9TxBWQDYLNomiG3h57Z3ukK-Nx1f4FnIvXdd1clb5HWGIOSdnOzqDFlRuKUMeENPpgusTjmvtHGgk6jrBjDZGCy9YS9HLW3TZ3lQiZjJ-FpTZ4o1vu-SgDmkWvMrui4zWeCZWHnLGkuAWvpmidb~2~2-Q~U-is5ZalhSXziLcbgs6BXmwkz6PutuA3idy1BQpZpAOkgyhQ49E~P6F5hCAD9J~EpvjJdd36kMw6HcM5apSpJkroA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. DC-10 induce Tr1 cells. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)] for 14 days. After stimulation, T cells were activated with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb and phorbol myristate acetate (TPA), and cytokine production was determined by intracytoplasmic staining and cytofluorometric analysis. (A) One representative experiment of 9 performed is presented. (B) Percentages of IFN-γ–, IL-2–, IL-4–, and IL-10–producing cells in T(iDC), T(DC-10), and T(mDC) cells generated from each of the 9 donors tested are presented. ***P ≤ .001, IL-10 production by T(DC-10) cells vs T(iDC) cells. °°P ≤ .01, °°°P ≤ .001, IL-10, IL-2, and IFN-γ production by T(DC-10) cells vs T(mDC) cells.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/6/10.1182_blood-2009-07-234872/4/m_zh89991055390004.jpeg?Expires=1765031137&Signature=ExFVWIWJTGKujupWHtO4px8Hz8QlFL0b~6NBwlDhisxkUlVywlNeRhz8gP4MTNnkiOdRtGPCHCB~BvVLMIbvDjEAw1gGDI91Y~1tfD3D41GZSaXBLzDFbJJsooH1Hvap-V-ZHZA4-5U0Dk8LEzS4dI9x8Unyig8fZkf2OkKYXPklX3fvNRCOTjSmreLFVrVx7KGU5BQM8Pjcxs1yVoTa2Fj922JVIregPllrbXyZV6rZWb5Sfhi19cU8Ge6k-I1ILaVZnBks9v1SbhQcKaUHd8GNyxAClUQ09q~V4mMl9TxY6y2BCimPMuw0AprHGQZRepMS74mTRsgVfTT~zJBaEw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. DC-10 induce Tr1 cell with suppressive activity. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic DC-10 [T(DC-10)] or myDCs [T(myDC)] isolated from peripheral blood by FACS sorting according to the expression of CD11c, CD83, and CD14, at the ratio of 10:1. After 14 days, T cells were tested for their ability to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with monocytes (MLR). Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocytes alone (MLR) or in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(myDC) cell lines at a 1:1 ratio. As control, T(DC-10) or T(myDC) cell lines were stimulated with monocytes. [3H]-thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Suppression of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in response to monocytes was measured in culture supernatants after 4 days of culture. Results representative of 2 independent experiments are shown. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic monocyte-derived iDCs [T(iDC)], DC-10 [T(DC-10)], or mDCs [T(mDC)]. After 14 days, T cells were tested for their ability to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR). Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs alone (MLR) or in the presence of T(iDC), T(DC-10), and T(mDC) cells at a 1:1 ratio. [3H]-Thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 8 independent experiments are shown. (D) Suppression of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in response to mDCs was measured in culture supernatants after 4 days of culture. Results representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Role of IL-10 and TGF-β in suppression mediated by T(DC-10) cells. After activation with DC-10, T(DC-10) cells were tested for their ability to suppress the IFN-γ production of CD4+ T cells in response to allogeneic monocytes in the absence or presence of anti–IL-10R (30 μg/mL) and anti–TGF-β (50 μg/mL) mAbs. Suppression of IFN-γ production was measured in culture supernatants 4 days after culture. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Autocrine IL-10 is required for the differentiation of T(DC-10) cells by DC-10. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic DC-10 in the presence of anti-IL10R (10 μg/mL) or control IgG (10 μg/mL) mAbs. After activation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to suppress the response of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 3 days of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results of one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. Numbers represent the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) compared with MLR alone.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/6/10.1182_blood-2009-07-234872/4/m_zh89991055390005.jpeg?Expires=1765031137&Signature=d71zlb9KLSBoNMExrc0QYysE0HaM5MTBtI3DtQJ9aNrpm1UmjRodcw3zfvatNM3yRDaJ6q7n-~AT99RgYjYLs0PqmXGLb2cpCoFn42Eq8eZfNnVgeViLl2HrdAjKLK6CBg3zNNcyyhC8ndh2weWKAQR8dt~QXfRuEAc~~kjpqtM3Q1GpuH50ZU7IgIs~iukJiAVT1BlABtkg9RNr~ais7pKVF1JobOzc89c~C6U7Vj03~ERn4mK7t5Cnmd-cdY1xxoD5Is1uQ6q9uc-NaETA1HJLWt8dkexB99LPVTlYbAze0QTJNImHYl-RCkrPhj53~~RA4QTwN5qrwfrNZeGE5g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Role of ILT4/HLA-G interaction in Tr1 cell differentiation. (A-B) Induction of Tr1 cells requires ILT4/HLA-G interaction. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-ILT4 [T(DC-10 anti-ILT4)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (A) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (B). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (A) and 4 days (B) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT4) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (A), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT4) cells compared with MLR alone (B). (C-D) IL-10 induces up-regulation of HLA-G on naive T cells. (C) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs for 48 hours, and T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of HLA-G. Percentages of HLA-G-positive cells obtained by stimulating naive CD4+ T cells with iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs from each of the 10 donors tested are presented. Black lines represent the mean percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived iDCs, DC-10, and mDCs for 48 hours in the presence of control IgG or anti-IL-10R mAbs. T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine levels of expression of HLA-G. Percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells are shown. Black lines represent the mean percentages of CD4+HLA-G+ T cells. (E-F) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-HLA-G [T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (E) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (F). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (E) and 4 days (F) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (E), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-HLA-G) cells compared with MLR alone (F).(G-H) Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with monocyte-derived DC-10 in the presence of anti-ILT2 [T(DC-10 anti-ILT2)] or control IgG [T(DC-10)] mAbs. As control, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with mDCs [T(mDC)]. After stimulation, T cells were collected and tested for their ability to proliferate in response to mDCs (G) and to suppress responses of autologous CD4+ T cells activated with mDCs (MLR) (H). [3H]-Thymidine was added after 2 days (G) and 4 days (H) of culture for an additional 16 hours. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers represent the percentage of anergy of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT2) cells compared with T(mDC) cells (G), and the percentage suppression of proliferation in MLR cocultured in the presence of T(DC-10) or T(DC-10 anti-ILT2) cells compared with MLR alone (H).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/6/10.1182_blood-2009-07-234872/4/m_zh89991055390007.jpeg?Expires=1765031137&Signature=0v0inSNSYgeeLkjSwxEiT3HU494k89ZFs6z9SvoFiE-MEUYi3k1qVsyEVWNVVe0~-bkJXASEnCtc6EBAAiMnFeg5uWdO36B39PFMDm1cbdsJwcJnJCpu4l6Ec-zBaK7yJAGOQ90uYWvDQT9wW~Z~luyxhelzS8E-w5gPC2HqagZxIBxDwzXwBeogDWauwgC4aG43LuLdinPddWmxn8kufaZTJqw0MmIww0VhtoRmNMRs63-RwGnEdOL4anispSv6hvy0c507C61mQnNNIABqGhcPThvpJn08FGQ3EQXg22o0S15Ub6M2pI1aG9pJYKU6pID4HHCFitk1S1DNARPeRw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)